SUMOylation Protects Endothelial Cell-Expressed Leukocyte-Specific Protein 1 from Ubiquitination-Mediated Proteasomal Degradation and Facilitates Its Nuclear Export

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

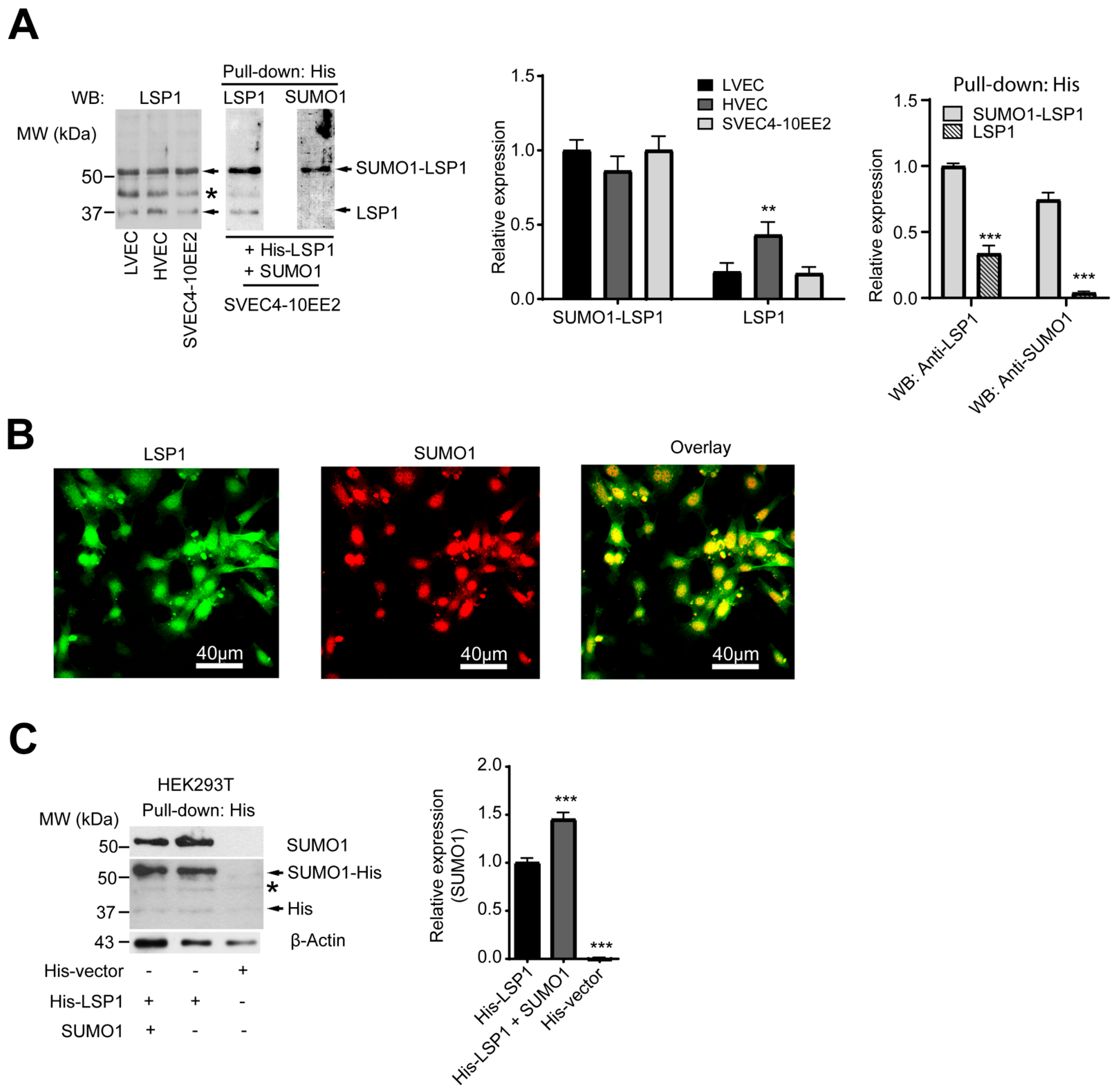

2.1. LSP1 Is SUMOylated

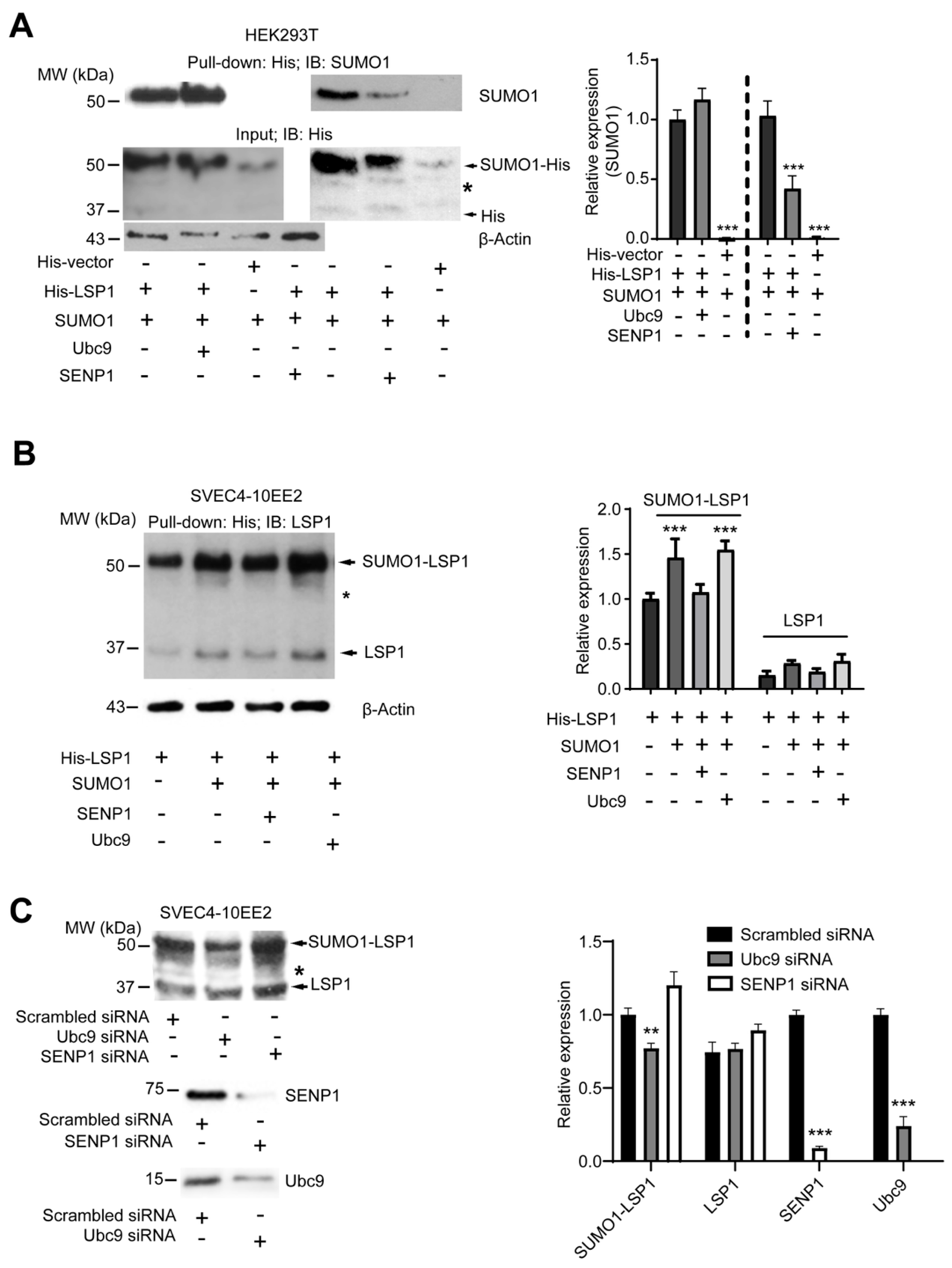

2.2. LSP1 SUMOylation Is Facilitated by Ubc9, Whereas Its deSUMOylation Is Mediated by SENP1

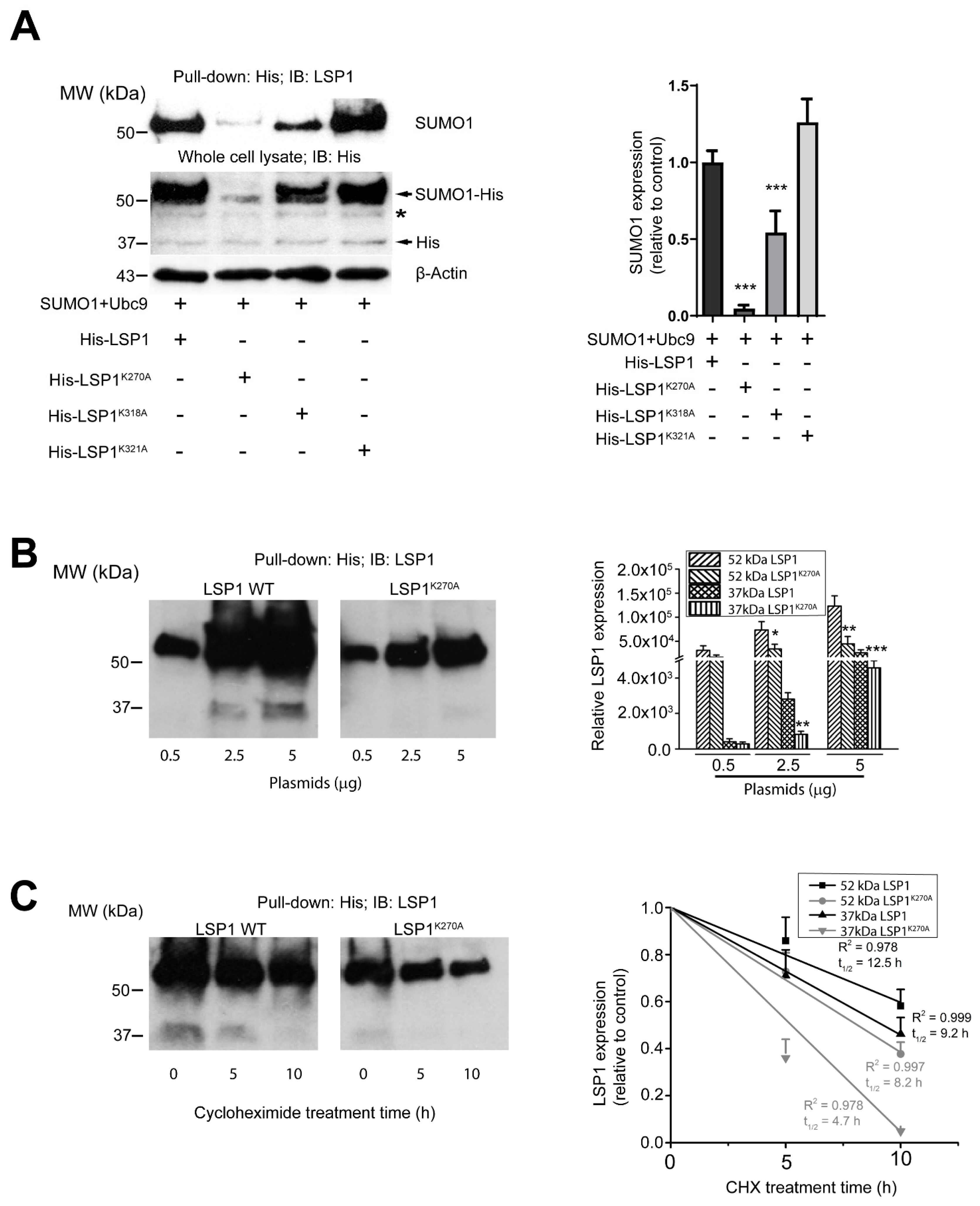

2.3. K270 and K318 Are the Primary Sites of LSP1 SUMOylation

2.4. DeSUMOylation Affects LSP1 Stability

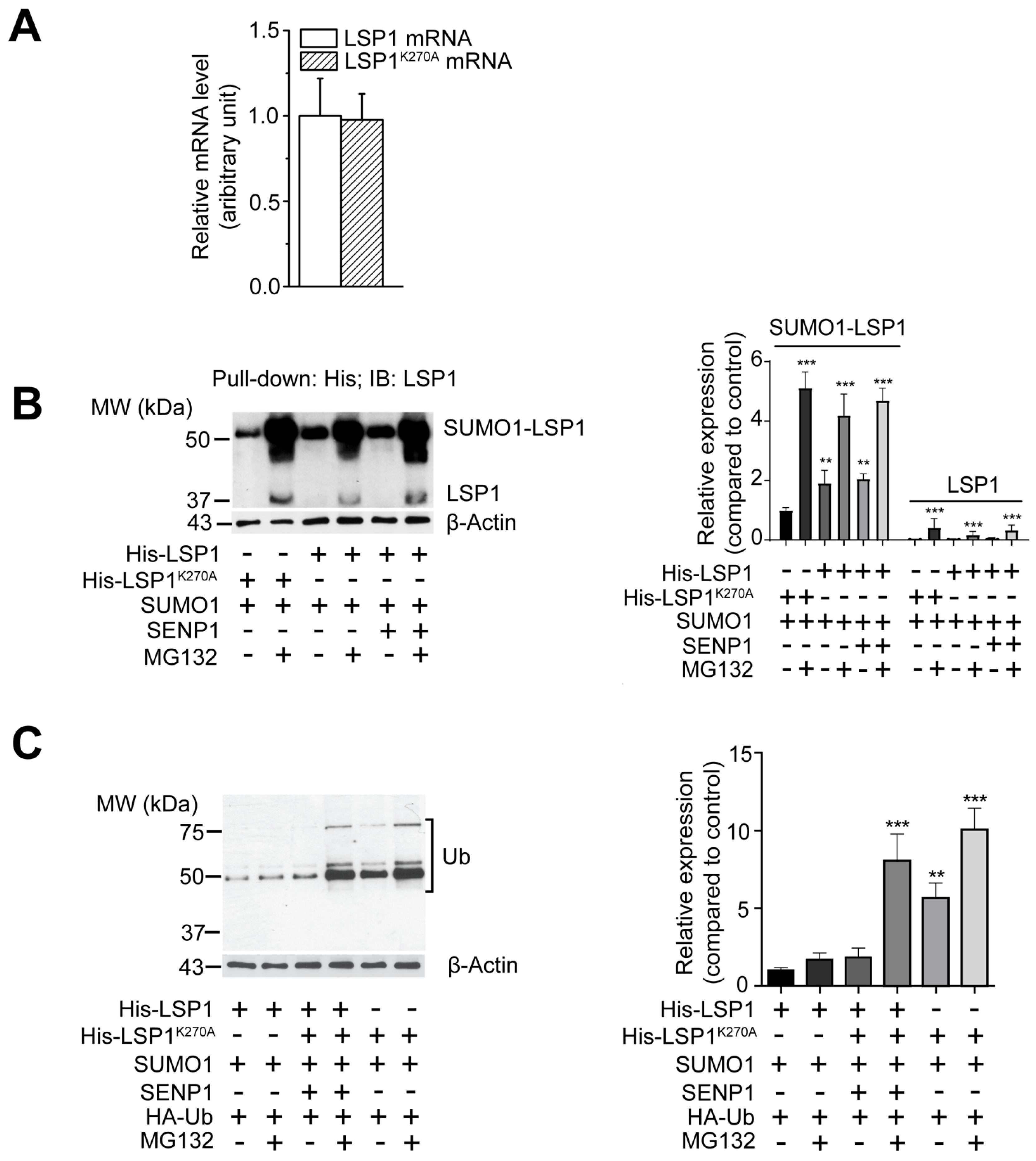

2.5. Enhanced Proteasomal Degradation of deSUMOylated LSP1 Due to Increased Ubiquitination

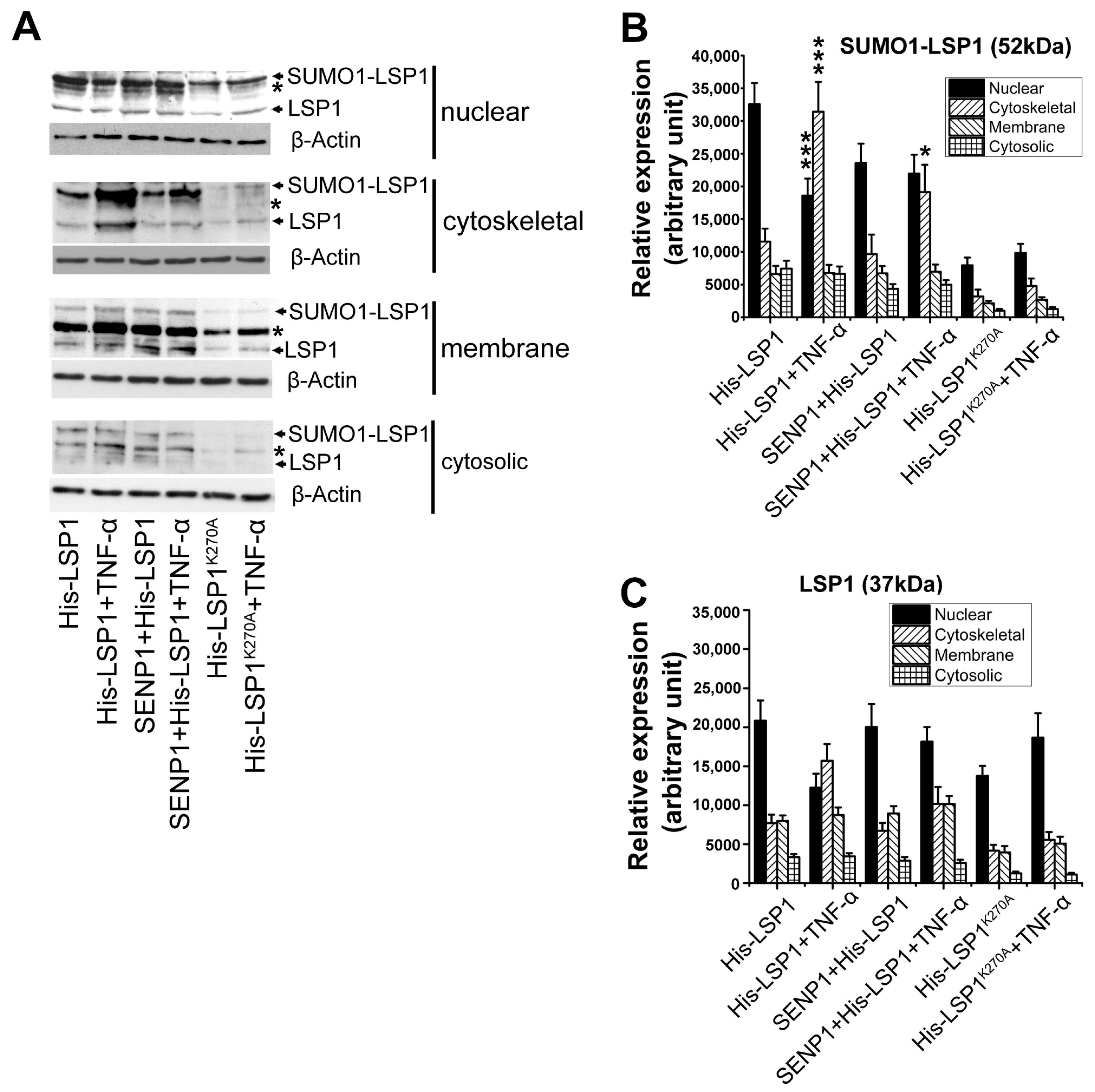

2.6. SUMOylation Deficiency Impairs Nucleus-to-Extranuclear Translocation of LSP1

3. Discussion

4. Experimental Procedure

4.1. Animals

4.2. Plasmids

- Mouse LSP1K270A forward: AGTCAGTCTGCTTCTGCGACACCCTCCTGCCAG;

- Mouse LSP1K270A reverse: CTGGCAGGAGGGTGTCGCAGAAGCAGACTGACT;

- Mouse LSP1K318A forward: GCCACTGGACATGGGGCGTACGAGAAAGTACT;

- Mouse LSP1K318A reverse: AGTACTTTCTCGTACGCCCCATGTCCAGTGGC;

- Mouse LSP1K321A forward: CATGGGAAGTACGAGGCAGTACTTGTGGATGAGGG;

- Mouse LSP1K321A reverse: CCCTCATCCACAAGTACTGCCTCGTACTTCCCATG.

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Harvest of Murine Primary Endothelial Cells

4.5. Cycloheximide Chase Assay

4.6. Proteasome Inhibition and In Vitro Ubiquitination Assay

4.7. Subcellular Fractionation

4.8. Nickel-Affinity Pull-Down

4.9. Immunoblotting

4.10. Mass Spectrometry

4.11. Real-Time Quantitative PCR

4.12. Confocal Microscopy

4.13. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Jongstra, J.; Tidmarsh, G.F.; Jongstra-Bilen, J.; Davis, M.M. A new lymphocyte-specific gene which encodes a putative Ca2+-binding protein is not expressed in transformed T lymphocyte lines. J. Immunol. 1988, 141, 3999–4004. [Google Scholar]

- Jongstra-Bilen, J.; Young, A.J.; Chong, R.; Jongstra, J. Human and mouse LSP1 genes code for highly conserved phosphoproteins. J. Immunol. 1990, 144, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulford, K.; Jones, M.; Banham, A.H.; Haralambieva, E.; Mason, D.Y. Lymphocyte-specific protein 1: A specific marker of human leucocytes. Immunology 1999, 96, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongstra, J.; Ittel, M.E.; Iscove, N.N.; Brady, G. The LSP1 gene is expressed in cultured normal and transformed mouse macrophages. Mol. Immunol. 1994, 31, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guerrero, A.; Howard, T.H. The actin-binding protein, lymphocyte-specific protein 1, is expressed in human leukocytes and human myeloid and lymphoid cell lines. J. Immunol. 1995, 155, 3563–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Cara, D.C.; Kaur, J.; Raharjo, E.; Mullaly, S.C.; Jongstra-Bilen, J.; Jongstra, J.; Kubes, P. LSP1 is an endothelial gatekeeper of leukocyte transendothelial migration. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiyala, R.K.; McIntyre, B.W.; Krensky, A.M. Molecular cloning and characterization of WP34, a phosphorylated human lymphocyte differentiation and activation antigen. Eur. J. Immunol. 1990, 20, 2417–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.K.; Zhan, L.; Ai, Y.; Jongstra, J. LSP1 is the major substrate for mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 2 in human neutrophils. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.P.; Jongstra-Bilen, J.; Ogryzlo, K.; Chong, R.; Jongstra, J. Lymphocyte-specific Ca2+-binding protein LSP1 is associated with the cytoplasmic face of the plasma membrane. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989, 9, 3043–3048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petri, B.; Kaur, J.; Long, E.M.; Li, H.; Parsons, S.A.; Butz, S.; Phillipson, M.; Vestweber, D.; Patel, K.D.; Robbins, S.M.; et al. Endothelial LSP1 is involved in endothelial dome formation, minimizing vascular permeability changes during neutrophil transmigration in vivo. Blood 2011, 117, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Hossain, M.; Qadri, S.M.; Liu, L. Different microvascular permeability responses elicited by the CXC chemokines MIP-2 and KC during leukocyte recruitment: Role of LSP1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 423, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, R.; Hong, B.K.; Lee, K.G.; Choi, E.; Sabbagh, L.; Cho, C.S.; Lee, N.; Kim, W.U. Regulation of tumor growth by leukocyte-specific protein 1 in T cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, X.; Min, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Qiao, K.; Xie, L.; Ren, J.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Leukocyte-specific protein 1 is associated with the stage and tumor immune infiltration of cervical cancer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongstra-Bilen, J.; Misener, V.L.; Wang, C.; Ginzberg, H.; Auerbach, A.; Joyner, A.L.; Downey, G.P.; Jongstra, J. LSP1 modulates leukocyte populations in resting and inflamed peritoneum. Blood 2000, 96, 1827–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Hayashi, H.; Harrison, R.; Chiu, B.; Chan, J.R.; Ostergaard, H.L.; Inman, R.D.; Jongstra, J.; Cybulsky, M.I.; Jongstra-Bilen, J. Modulation of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18)-mediated adhesion by the leukocyte-specific protein 1 is key to its role in neutrophil polarization and chemotaxis. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Bi, H.; Chang, A.K.; Zang, M.X.; Wang, M.; Ao, X.; Li, S.; Pan, H.; Guo, Q.; Wu, H. SUMOylation of AhR modulates its activity and stability through inhibiting its ubiquitination. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012, 227, 3812–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Sumoylation regulates diverse biological processes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 3017–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, M.S.; Dargemont, C.; Hay, R.T. SUMO-1 conjugation in vivo requires both a consensus modification motif and nuclear targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 12654–12659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R.T. SUMO: A history of modification. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, E.T. SUMOylation and De-SUMOylation: Wrestling with life’s processes. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 8223–8227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, C.D.; Reverter, D. Structure of the human SENP7 catalytic domain and poly-SUMO deconjugation activities for SENP6 and SENP7. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 32045–32055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Yao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, L.; Ma, Y.; Dai, W. Sumoylation is important for stability, subcellular localization, and transcriptional activity of SALL4, an essential stem cell transcription factor. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 38600–38608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cristofaro, T.; Mascia, A.; Pappalardo, A.; D’Andrea, B.; Nitsch, L.; Zannini, M. Pax8 protein stability is controlled by sumoylation. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009, 42, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Hannoun, Z.; Jaffray, E.; Medine, C.N.; Black, J.R.; Greenhough, S.; Zhu, L.; Ross, J.A.; Forbes, S.; Wilmut, I.; et al. SUMOylation of HNF4alpha regulates protein stability and hepatocyte function. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 3630–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjenseth, A.; Fykerud, T.A.; Sirnes, S.; Bruun, J.; Yohannes, Z.; Kolberg, M.; Omori, Y.; Rivedal, E.; Leithe, E. The gap junction channel protein connexin 43 is covalently modified and regulated by SUMOylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 15851–15861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehennaut, V.; Loison, I.; Dubuissez, M.; Nassour, J.; Abbadie, C.; Leprince, D. DNA double-strand breaks lead to activation of hypermethylated in cancer 1 (HIC1) by SUMOylation to regulate DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 10254–10264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Saunier, E.F.; Akhurst, R.J.; Derynck, R. The type I TGF-beta receptor is covalently modified and regulated by sumoylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazono, K.; Kamiya, Y.; Miyazawa, K. SUMO amplifies TGF-beta signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeKroon, R.M.; Robinette, J.B.; Osorio, C.; Jeong, J.S.; Hamlett, E.; Mocanu, M.; Alzate, O. Analysis of protein posttranslational modifications using DIGE-based proteomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012, 854, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.X.; Bialkowska, A.B.; McConnell, B.B.; Yang, V.W. SUMOylation regulates nuclear localization of Kruppel-like factor 5. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 31991–32002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ma, Y.; Qian, L.; Wang, J. Sumoylation regulates nuclear localization and function of zinc finger transcription factor ZIC3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2013, 1833, 2725–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Yamada, S.; Lualdi, M.; Dasso, M.; Kuehn, M.R. Senp1 is essential for desumoylating Sumo1-modified proteins but dispensable for Sumo2 and Sumo3 deconjugation in the mouse embryo. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Itoh, K. Characterization of a novel posttranslational modification in neuronal nitric oxide synthase by small ubiquitin-related modifier-1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1814, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenk, C.; Humrich, J.; Quitterer, U.; Lohse, M.J. SUMO-1 controls the protein stability and the biological function of phosducin. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 8357–8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S.; Li, H.; Dong, W.; Krasinska, K.; Adams, C.; Alexandrova, L.; Chien, A.; Hallows, K.R.; Bhalla, V. Neural precursor cell-expressed developmentally down-regulated protein 4-2 (Nedd4-2) regulation by 14-3-3 protein binding at canonical serum and glucocorticoid kinase 1 (SGK1) phosphorylation sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 37830–37840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkholz, J.; Michalick, L.; Munz, B. The E3 SUMO ligase Nse2 regulates sumoylation and nuclear-to-cytoplasmic translocation of skNAC-Smyd1 in myogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 3794–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, W.O.; Jaffray, E.; Campbell, S.G.; Takeda, S.; Bayston, L.J.; Basu, S.P.; Li, M.; Raftery, L.A.; Ashe, M.P.; Hay, R.T.; et al. Medea SUMOylation restricts the signaling range of the Dpp morphogen in the Drosophila embryo. Genes. Dev. 2008, 22, 2578–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Howard, T.H. Human lymphocyte-specific protein 1, the protein overexpressed in neutrophil actin dysfunction with 47-kDa and 89-kDa protein abnormalities (NAD 47/89), has multiple F-actin binding domains. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 2052–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, N.; Kita, K.; Kojima, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Irimura, T.; Miyagi, M.; Tsunasawa, S.; Toyoshima, S. Lymphocyte isoforms of mouse p50 LSP1, which are phosphorylated in mitogen-activated T cells, are formed through alternative splicing and phosphorylation. J. Biochem. 1995, 118, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, R.; Delphin, C.; Guan, T.; Gerace, L.; Melchior, F. A small ubiquitin-related polypeptide involved in targeting RanGAP1 to nuclear pore complex protein RanBP2. Cell 1997, 88, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagey, M.H.; Melhuish, T.A.; Wotton, D. The Polycomb Protein Pc2 Is a SUMO E3. Cell 2003, 113, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi, Y.; Yogosawa, S.; Honda, R.; Nishida, T.; Yasuda, H. Sumoylation of Mdm2 by Protein Inhibitor of Activated STAT (PIAS) and RanBP2 Enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 50131–50136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.-S.; Ryu, S.-W.; Kim, E. Modification of Daxx by small ubiquitin-related modifier-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 295, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoege, C.; Pfander, B.; Moldovan, G.-L.; Pyrowolakis, G.; Jentsch, S. RAD6-dependent DNA repair is linked to modification of PCNA by ubiquitin and SUMO. Nature 2002, 419, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matic, I.; Schimmel, J.; Hendriks, I.A.; van Santen, M.A.; van de Rijke, F.; van Dam, H.; Gnad, F.; Mann, M.; Vertegaal, A.C. Site-specific identification of SUMO-2 targets in cells reveals an inverted SUMOylation motif and a hydrophobic cluster SUMOylation motif. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palczewska, M.; Casafont, I.; Ghimire, K.; Rojas, A.M.; Valencia, A.; Lafarga, M.; Mellstrom, B.; Naranjo, J.R. Sumoylation regulates nuclear localization of repressor DREAM. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2011, 1813, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Klenk, C.; Liu, B.; Keiner, B.; Cheng, J.; Zheng, B.J.; Li, L.; Han, Q.; Wang, C.; Li, T.; et al. Modification of nonstructural protein 1 of influenza A virus by SUMO1. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, H. Stability of zinc finger nuclease protein is enhanced by the proteasome inhibitor MG132. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liang, M.; Liang, Y.-Y.; Brunicardi, F.C.; Feng, X.-H. SUMO-1/Ubc9 Promotes Nuclear Accumulation and Metabolic Stability of Tumor Suppressor Smad4. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 31043–31048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bies, J.; Markus, J.; Wolff, L. Covalent attachment of the SUMO-1 protein to the negative regulatory domain of the c-Myb transcription factor modifies its stability and transactivation capacity. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 8999–9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehat, B.; Tofigh, A.; Lin, Y.; Trocme, E.; Liljedahl, U.; Lagergren, J.; Larsson, O. SUMOylation mediates the nuclear translocation and signaling of the IGF-1 receptor. Sci. Signal 2010, 3, ra10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.T.; Wuerzberger-Davis, S.M.; Wu, Z.-H.; Miyamoto, S. Sequential Modification of NEMO/IKKγ by SUMO-1 and Ubiquitin Mediates NF-κB Activation by Genotoxic Stress. Cell 2003, 115, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.D.; Irvin, B.J.; Nucifora, G.; Luce, K.S.; Hiebert, S.W. Small ubiquitin-like modifier conjugation regulates nuclear export of TEL, a putative tumor suppressor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 3257–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, A.; Li, D.; Zhao, L.Y.; Godsey, A.; Liao, D. p53 SUMOylation promotes its nuclear export by facilitating its release from the nuclear export receptor CRM1. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 2739–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitani, T.; Kito, K.; Nguyen, H.P.; Yeh, E.T. Characterization of NEDD8, a developmentally down-regulated ubiquitin-like protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 28557–28562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Qadri, S.M.; Su, Y.; Liu, L. ICAM-1-mediated leukocyte adhesion is critical for the activation of endothelial LSP1. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013, 304, C895–C904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Qadri, S.M.; Cayabyab, F.S.; Wu, L.; Liu, L. Regulation of methylglyoxal-elicited leukocyte recruitment by endothelial SGK1/GSK3 signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 2481–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Species | Position | Group | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mouse | K318 | VATGH GKYE KVLVD | 0.67 |

| Human | K327 | VATGH GKYE KVLVE | 0.67 | |

| 2 | Mouse | K270 | QSQSA SKTP SCQDI | --- |

| Human | K279 | QAQSA AKTP SCKDI | 0.69 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hossain, M.; Huang, J.; Su, Y.; Islam, M.R.; Rahman, M.A.; Cayabyab, F.S.; Liu, L. SUMOylation Protects Endothelial Cell-Expressed Leukocyte-Specific Protein 1 from Ubiquitination-Mediated Proteasomal Degradation and Facilitates Its Nuclear Export. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021111

Hossain M, Huang J, Su Y, Islam MR, Rahman MA, Cayabyab FS, Liu L. SUMOylation Protects Endothelial Cell-Expressed Leukocyte-Specific Protein 1 from Ubiquitination-Mediated Proteasomal Degradation and Facilitates Its Nuclear Export. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021111

Chicago/Turabian StyleHossain, Mokarram, Jiannan Huang, Yang Su, Md Rafikul Islam, Mohammad Alinoor Rahman, Francisco S. Cayabyab, and Lixin Liu. 2026. "SUMOylation Protects Endothelial Cell-Expressed Leukocyte-Specific Protein 1 from Ubiquitination-Mediated Proteasomal Degradation and Facilitates Its Nuclear Export" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021111

APA StyleHossain, M., Huang, J., Su, Y., Islam, M. R., Rahman, M. A., Cayabyab, F. S., & Liu, L. (2026). SUMOylation Protects Endothelial Cell-Expressed Leukocyte-Specific Protein 1 from Ubiquitination-Mediated Proteasomal Degradation and Facilitates Its Nuclear Export. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021111