Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogenetic Analysis and Salt-Responsive Expression Profiling of the MYB Transcription Factor Family in Cannabis sativa L. During Seed Germination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of MYB Genes in C. sativa

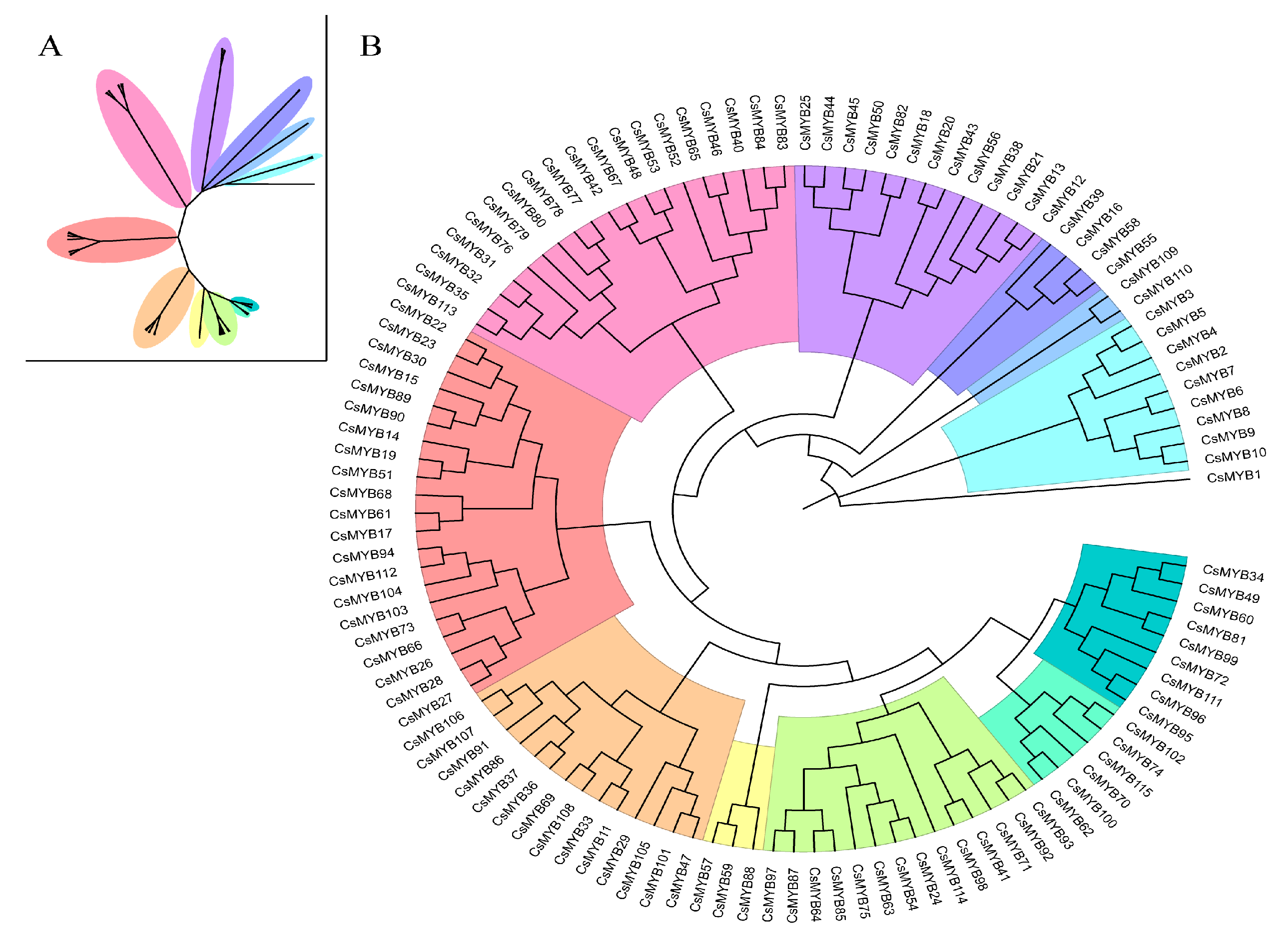

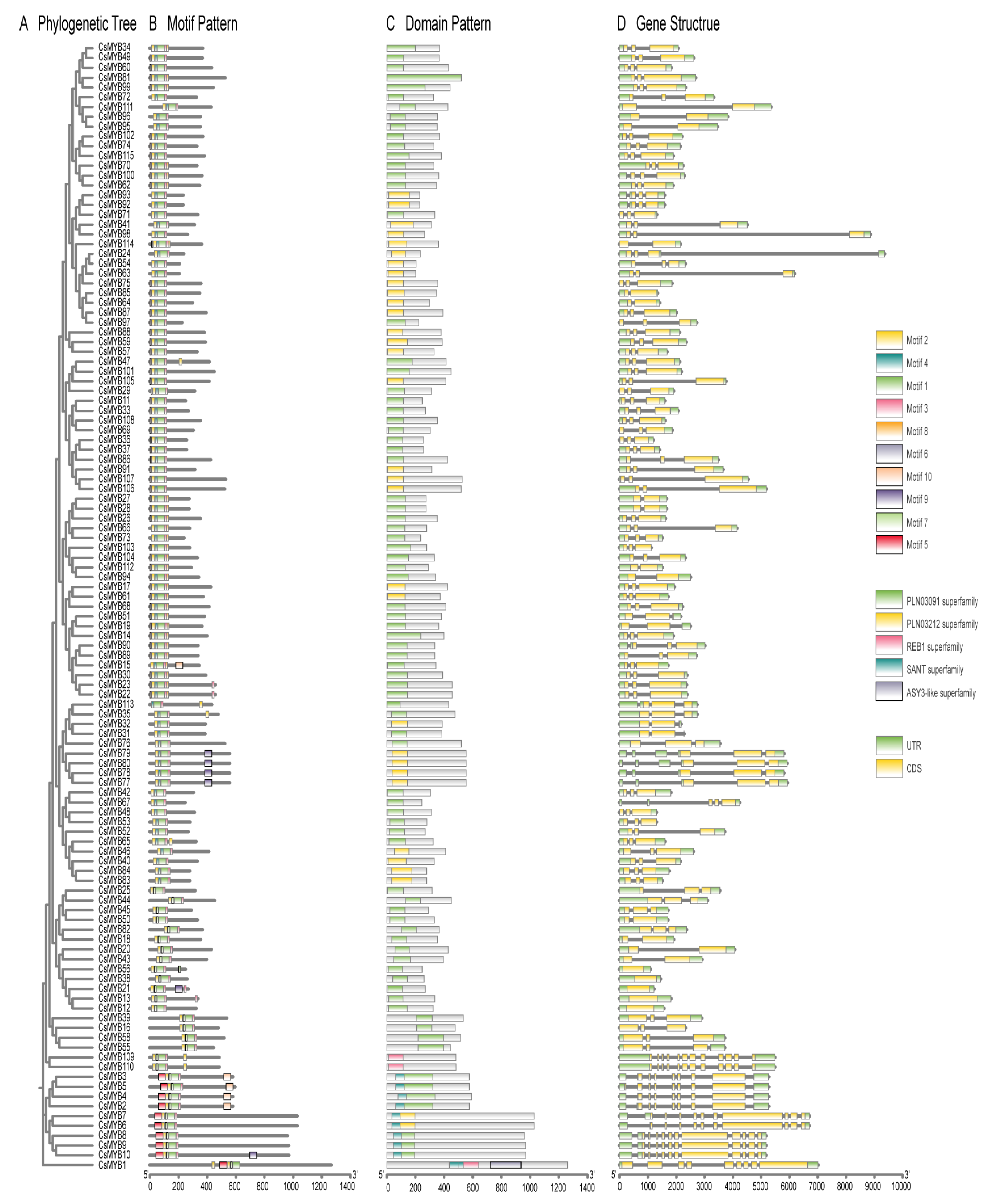

2.2. Phylogenetic Classification and Motif Analysis

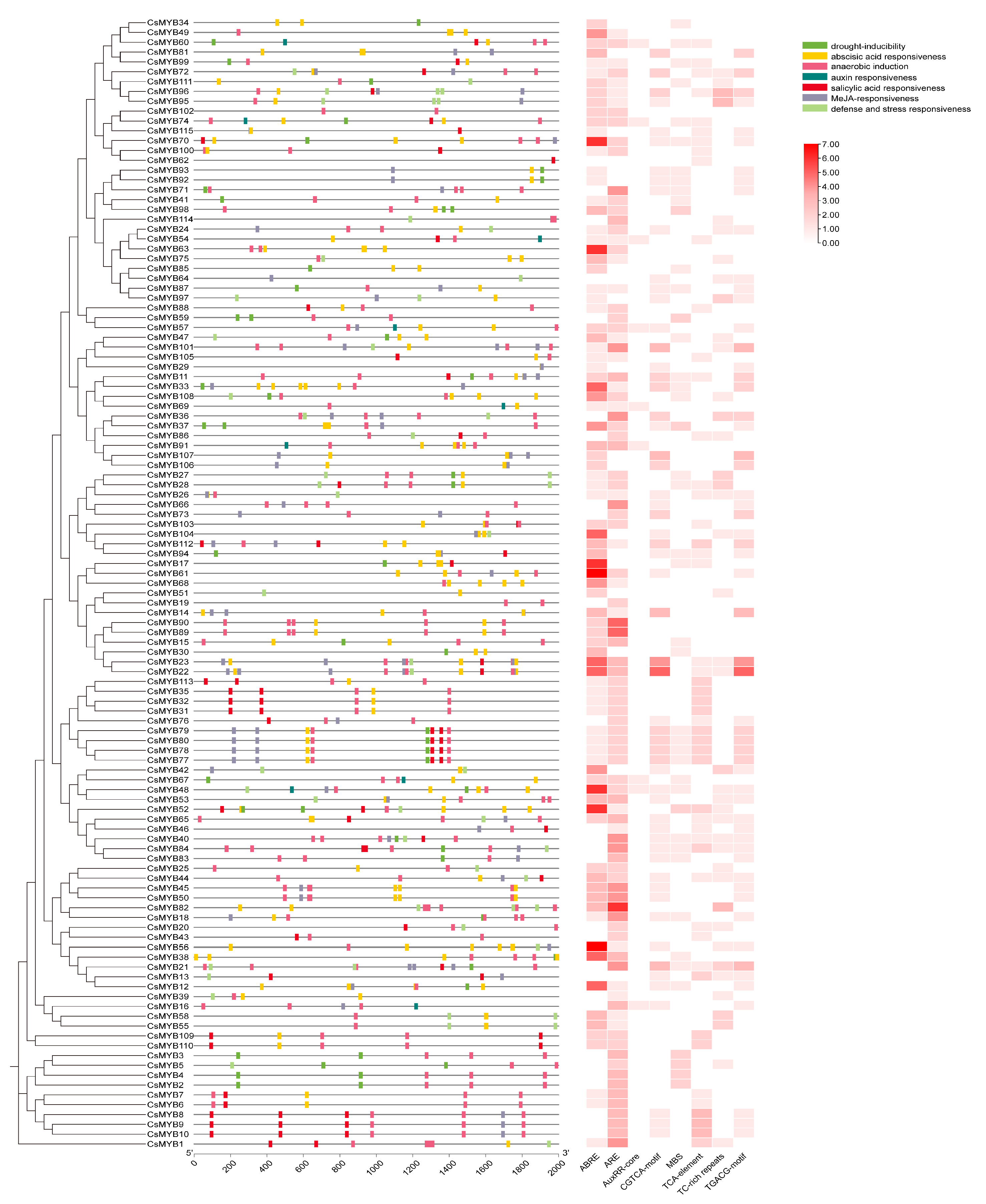

2.3. Gene Structure and Promoter Analysis

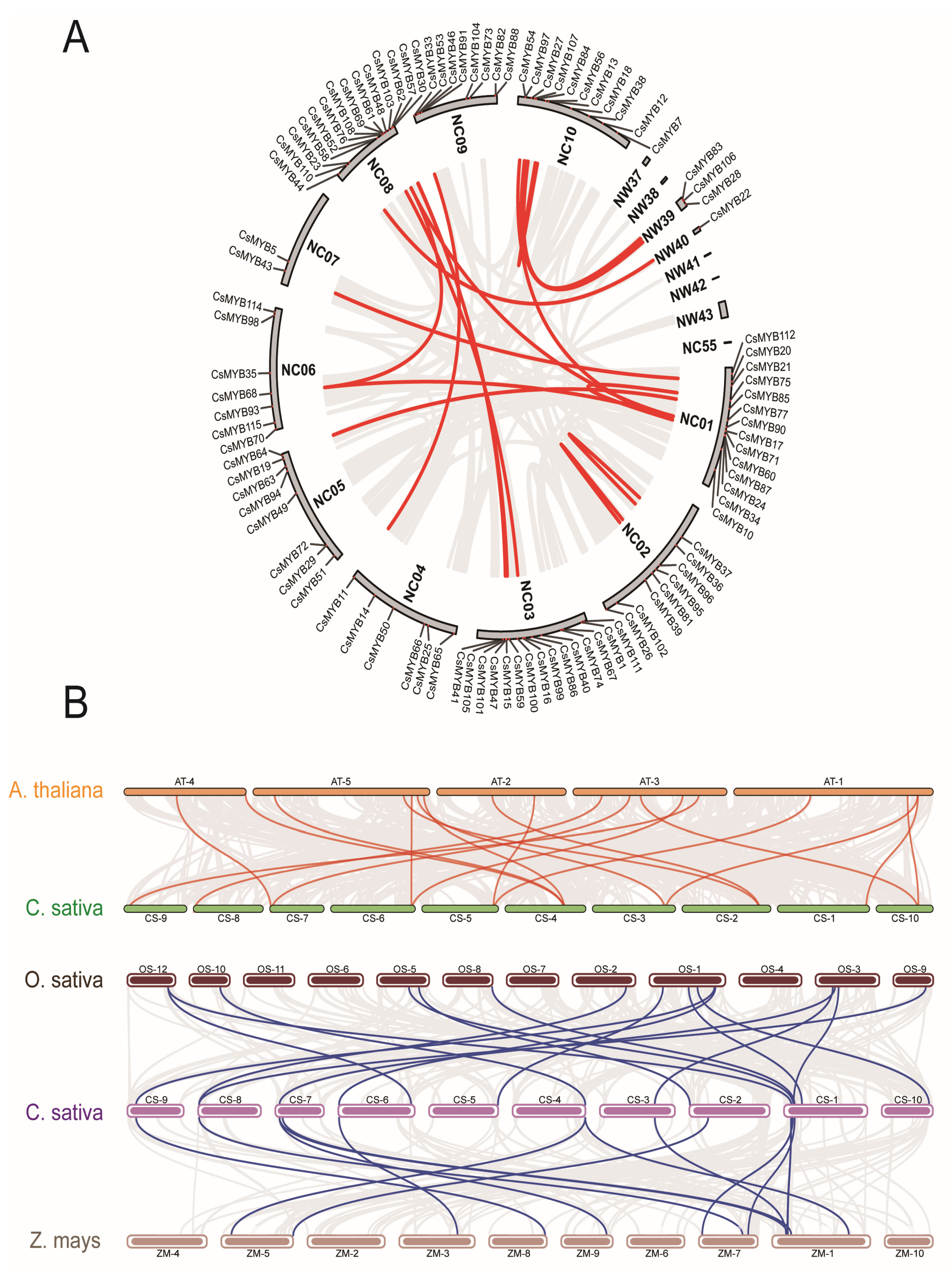

2.4. CsMYBs Chromosome Distribution and Synteny Analysis

2.5. Expression Profiles Under Salt Stress and During Germination

2.5.1. RNA-Seq Analysis and Candidate Gene Selection

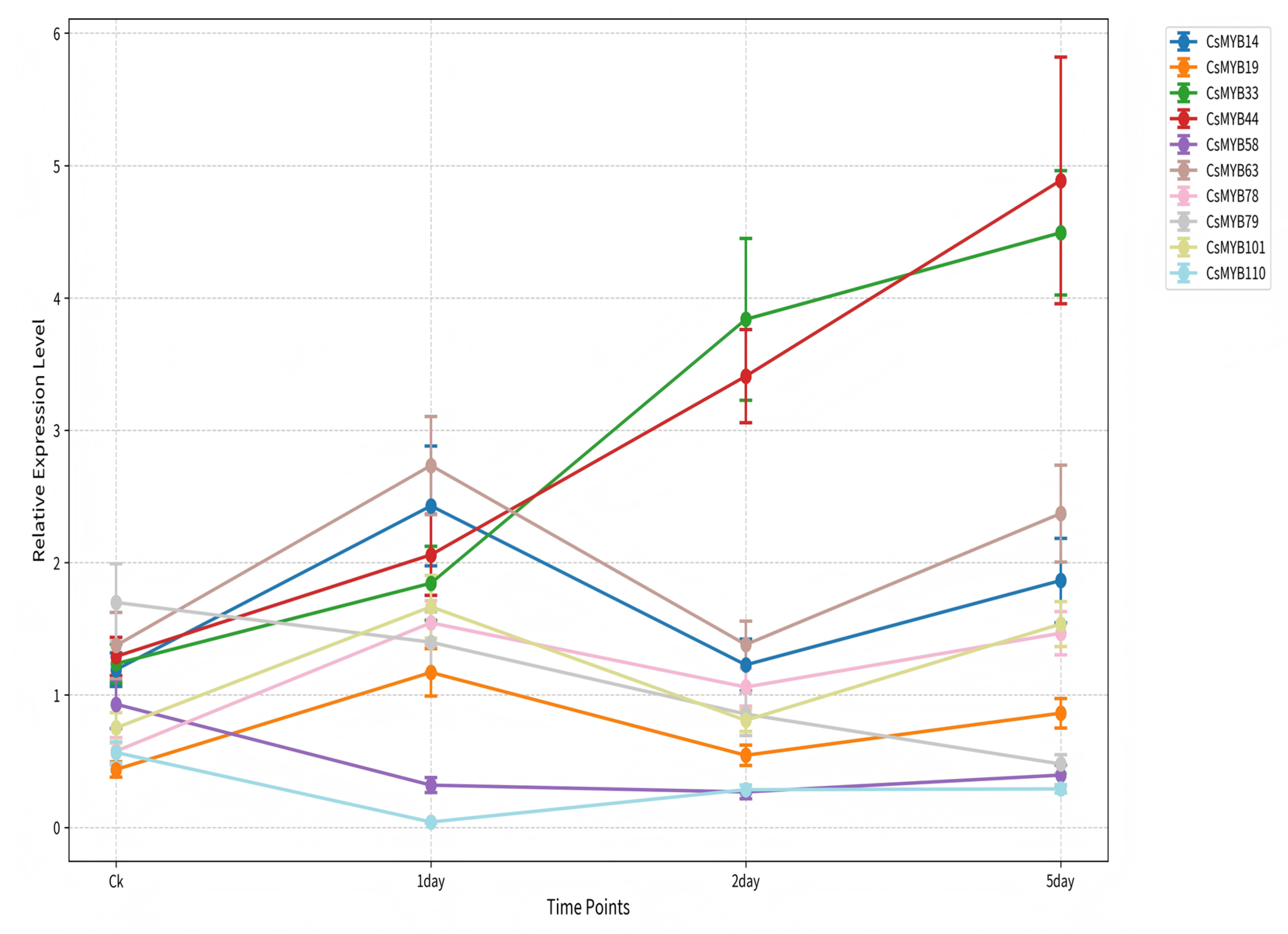

2.5.2. Temporal Expression Dynamics via qRT-PCR

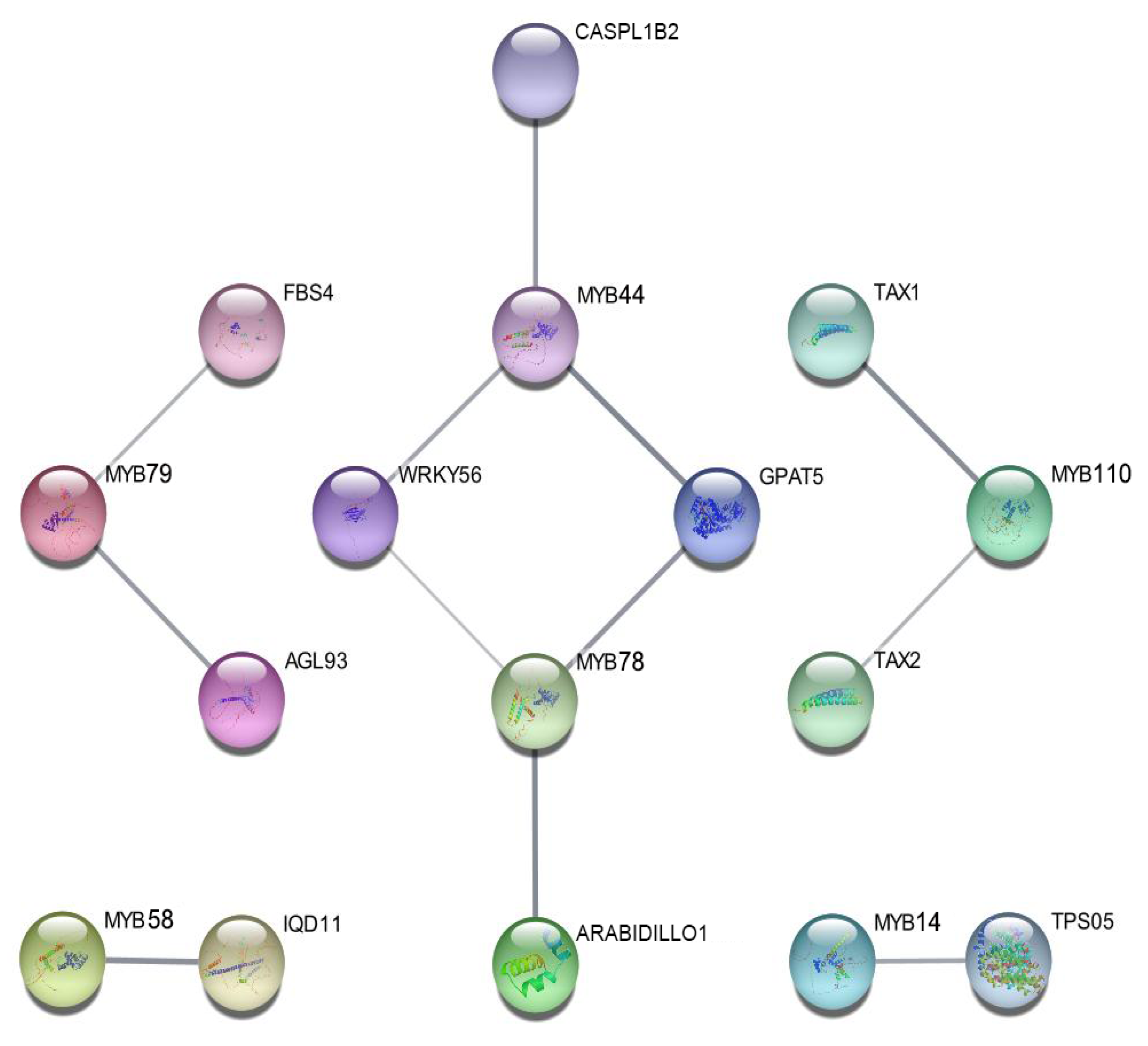

2.6. Protein–Protein Interaction and Regulatory Network Analysis of CsMYB

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Seed Germination Conditions

4.2. Identification of MYB Genes in C. sativa

4.3. Phylogenetic, Motif, and Gene Structure Analysis

4.4. Promoter Cis-Element Analysis

4.5. Synteny Analysis

4.6. Expression Analysis of Salt Stress Related CsMYBs During Seed Germination

4.6.1. RNA-Sequencing and Candidate Gene Selection

4.6.2. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Validation

4.7. Protein–Protein Interaction Network Prediction

4.8. Statistical Analsysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, J.K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The physiology of plant responses to drought. Science 2020, 368, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, Y. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms mediating plant salt-stress responses. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 523–539. [Google Scholar]

- Kissoudis, C.; van de Wiel, C.; Visser, R.G.F.; van der Linden, G. Future-proof crops for multiple abiotic stresses: The case of drought and heat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2016, 133, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.T.; Ma, S.L.; Bai, L.P.; Ma, H.; Jia, P.; Liu, J.; Zhong, M. Signal transduction during cold, salt, and drought stresses in plants. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dubos, C.; Stracke, R.; Grotewold, E.; Weisshaar, B.; Martin, C.; Lepiniec, L. MYB transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Tang, P.; Li, X.; Haroon, A.; Nasreen, S.; Noor, H.; Attia, K.A.; Abushady, A.M.; Wang, R.; Cui, K.; et al. Genome-wide identification, phylogeny and expression analysis of the R2R3-MYB gene family in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) under abiotic stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 2024, 51, FP23261. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, H.; Li, J.; Liu, P.; Duan, J.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ali, J.; Li, Z. Overexpression of OsMYB48-1, a Novel MYB-Related Transcription Factor, Enhances Drought and Salinity Tolerance in Rice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92913. [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu, M.C.; Inal, B.; Kavas, M.; Unver, T. Diverse expression pattern of wheat transcription factors against abiotic stresses in wheat species. Gene 2014, 550, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.K.; Cao, Z.H.; Hao, Y.J. Overexpression of a R2R3 MYB gene MdSIMYB1 increases tolerance to multiple stresses in transgenic tobacco and apples. Physiol. Plant. 2013, 150, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q.; Zhang, F.; Sun, F.; Luo, Q.; Wang, R.; Hu, R.; Chen, M.; Chang, J.; Yang, G.; He, G. A wheat MYB transcriptional repressor TaMyb1D regulates phenylpropanoid metabolism and enhances tolerance to drought and oxidative stresses in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Sci. 2017, 265, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Deng, G.; Su, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Du, G.H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Liu, F.H. Protein mechanisms in response to NaCl-stress of salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive industrial hemp based on iTRAQ technology. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 83, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverty, K.U.; Stout, J.M.; Sullivan, M.J.; Shah, H.; Gill, N.; Holbrook, L.; Page, J.E. A physical and genetic map of Cannabis sativa identifies extensive rearrangements at the THC/CBD acid synthase loci. Genome Res. 2019, 29, 146–156. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, D.; Che, Y.; Amanullah, S.; Zhang, L.; Jie, S.; Yang, W.; Wang, M.; Wang, L.; Qi, G. Transcriptomic sequencing and expression verification of identified genes modulating the alkali stress tolerance and endogenous photosynthetic activities of industrial hemp plant. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326434. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; He, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, M. Transcription factor DIVARI-CATA1 positively modulates seed germination in response to salinity stress. Plant Physiol. 2024, 4, 2997–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Bian, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, P.; Gao, B.; Sun, X.; Hu, M.; et al. The miRNA–mRNA regulatory networks of the response to NaHCO3 stress in industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 509. [Google Scholar]

- Ambawat, S.; Sharma, P.; Yadav, N.R.; Yadav, R.C. MYB transcription factor genes as regulators for plant responses: An overview. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2013, 19, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katiyar, A.; Smita, S.; Lenka, S.K.; Rajwanshi, R.; Chinnusamy, V.; Bansal, K.C. Genome-wide classification and expression analysis of MYB transcription factor families in rice and Arabidopsis. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; He, K.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Gao, Z.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Qiu, X.; et al. The MYB transcription factor superfamily of Arabidopsis: Expression analysis and phylogenetic comparison with the rice MYB family. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 60, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Osbourn, A.; Ma, P. MYB Transcription Factors as Regulators of Phenylpropanoid Metabolism in Plants. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S. Function of MYB domain transcription factors in abiotic stress and epigenetic control of stress response in plant genome. Plant Signal. Behav. 2016, 11, e1117723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, P.J.; Xiang, F.; Qiao, M.; Park, J.Y.; Lee, Y.N.; Kim, S.G.; Park, C.M. The MYB96 transcription factor mediates abscisic acid signaling during drought stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, R.; An, X. Research progress of MYB transcription factor family in plant stress resistance. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2024, 52, 13491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xia, M.; Su, P.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, L.; Zhao, H.; Gao, W.; Huang, L.; Hu, Y. MYB transcription factors in plants: A comprehensive review of their discovery, structure, classification, functional diversity and regulatory mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 2, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, W.; Lv, J.; Jia, Y.; Wang, M.; Xia, G. Ectopic expression of a wheat MYB transcription factor gene, TaMYB73, improves salinity stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 1511–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.E.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, J.H.; Noh, H.; Hong, S.W.; Lee, H. A dual role of MYB60 in stomatal regulation and root growth of Arabidopsis thaliana under drought stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011, 77, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Laun, T.; Zimmermann, P.; Zentgraf, U. Targets of the WRKY53 transcription factor and its role during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004, 55, 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni, R.; Thiry, M.; Hausman, J.F.; Lutts, S.; Guerriero, G. Eustress and Plants: A Synthesis with Prospects for Cannabis sativa Cultivation. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Jia, D.; Li, A.; Zhang, H.; Tian, S.; Zhang, X.; Jing, R. Transgenic expression of TaMYB2A confers enhanced tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2011, 11, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Jiang, H.; Mao, Z.; Wang, N.; Jiang, S.; Xu, H.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor MdMYB24-like is involved in methyl jasmonate-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in apple. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 56, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.K.; Agarwal, P.; Reddy, M.K.; Sopory, S.K. Role of DREB transcription factors in abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2006, 25, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Zou, H.F.; Wang, H.W.; Zhang, W.K.; Ma, B.; Zhang, J.S.; Chen, S.Y. Soybean GmMYB76, GmMYB92, and GmMYB177 genes confer stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vannini, C.; Locatelli, F.; Bracale, M.; Magnani, E.; Marsoni, M.; Osnato, M.; Coraggio, I. Overexpression of the rice Osmyb4 gene increases chilling and freezing tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Plant J. 2004, 37, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Fan, L.M. MYB transcription factors, active players in abiotic stress signaling. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 114, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Song, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Zou, C.; Yu, D. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant abiotic stresses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1819, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, D.; Liang, S.; Che, Y.; Qi, G.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhao, H.; Chen, J.; Zhu, A.; Gao, G. Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogenetic Analysis and Salt-Responsive Expression Profiling of the MYB Transcription Factor Family in Cannabis sativa L. During Seed Germination. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021087

Wang D, Liang S, Che Y, Qi G, Jiang Z, Yang W, Zhao H, Chen J, Zhu A, Gao G. Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogenetic Analysis and Salt-Responsive Expression Profiling of the MYB Transcription Factor Family in Cannabis sativa L. During Seed Germination. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021087

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Di, Shuyue Liang, Ye Che, Guochao Qi, Zeyu Jiang, Wei Yang, Haohan Zhao, Jikang Chen, Aiguo Zhu, and Gang Gao. 2026. "Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogenetic Analysis and Salt-Responsive Expression Profiling of the MYB Transcription Factor Family in Cannabis sativa L. During Seed Germination" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021087

APA StyleWang, D., Liang, S., Che, Y., Qi, G., Jiang, Z., Yang, W., Zhao, H., Chen, J., Zhu, A., & Gao, G. (2026). Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogenetic Analysis and Salt-Responsive Expression Profiling of the MYB Transcription Factor Family in Cannabis sativa L. During Seed Germination. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1087. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021087