Early Molecular Biomarkers in an Amyloid-β-Induced Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: Effects of Kelulut Honey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

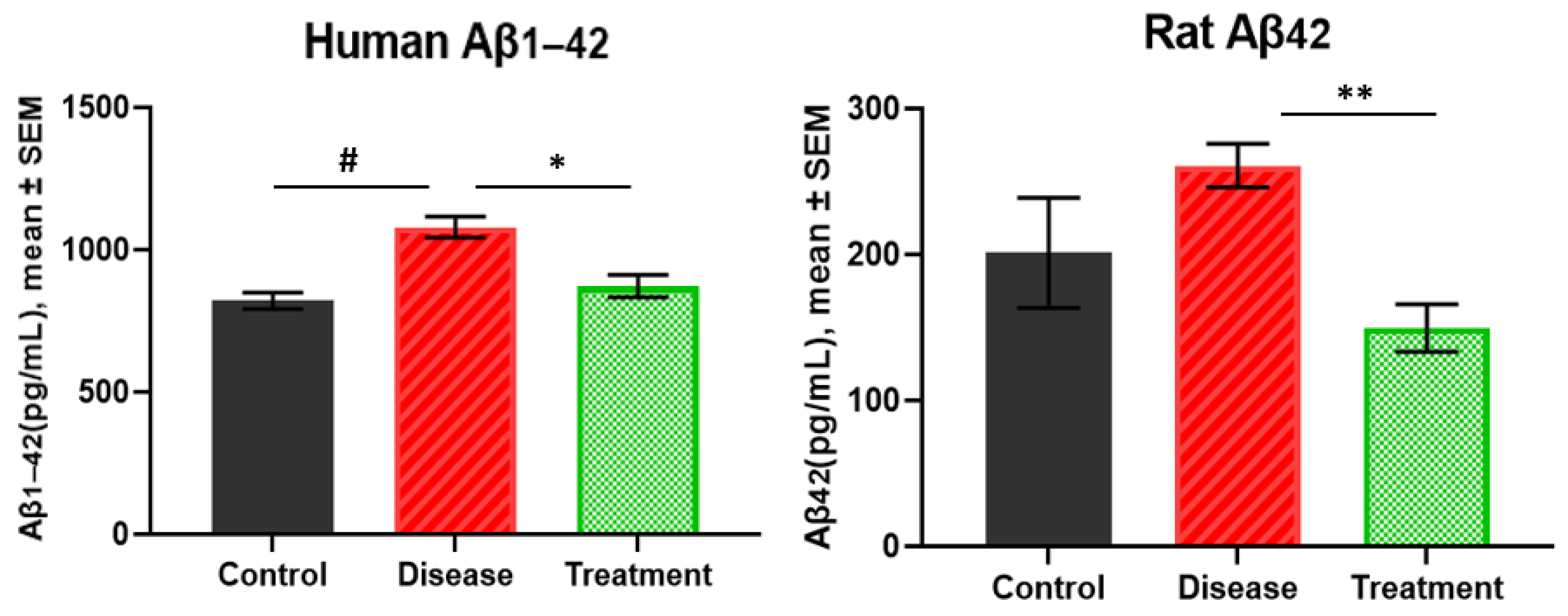

2.1. Human Amyloid β1-42 and Rat Amyloid β42 Levels in Brain

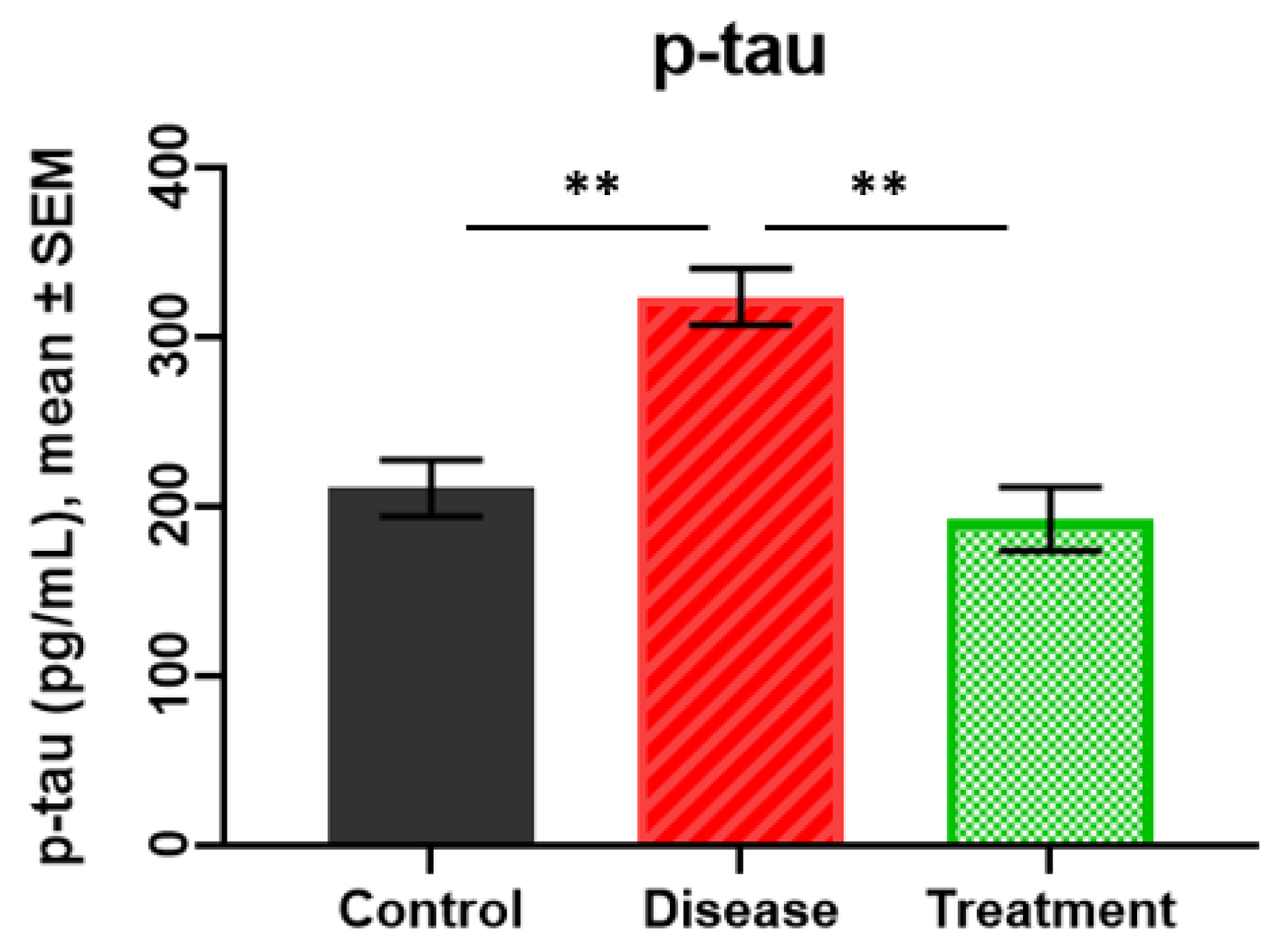

2.2. p-tau Levels

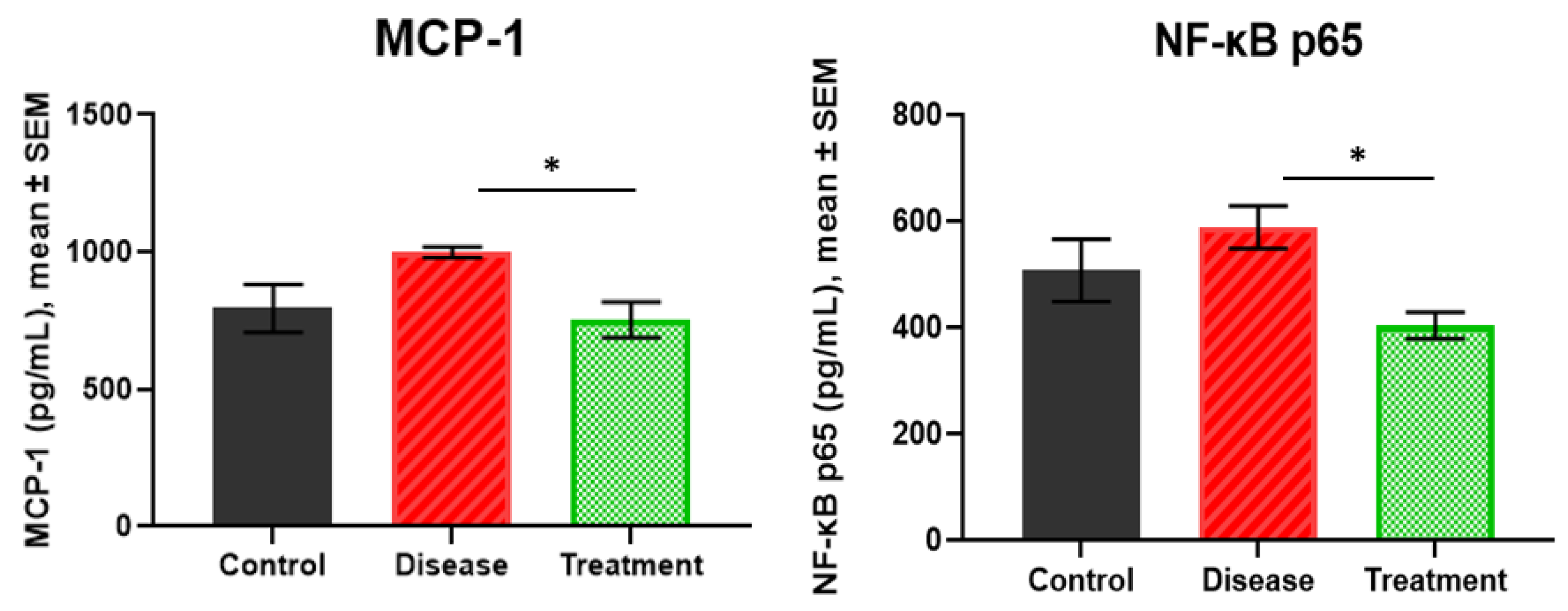

2.3. MCP-1 and NF-κB p65 Levels

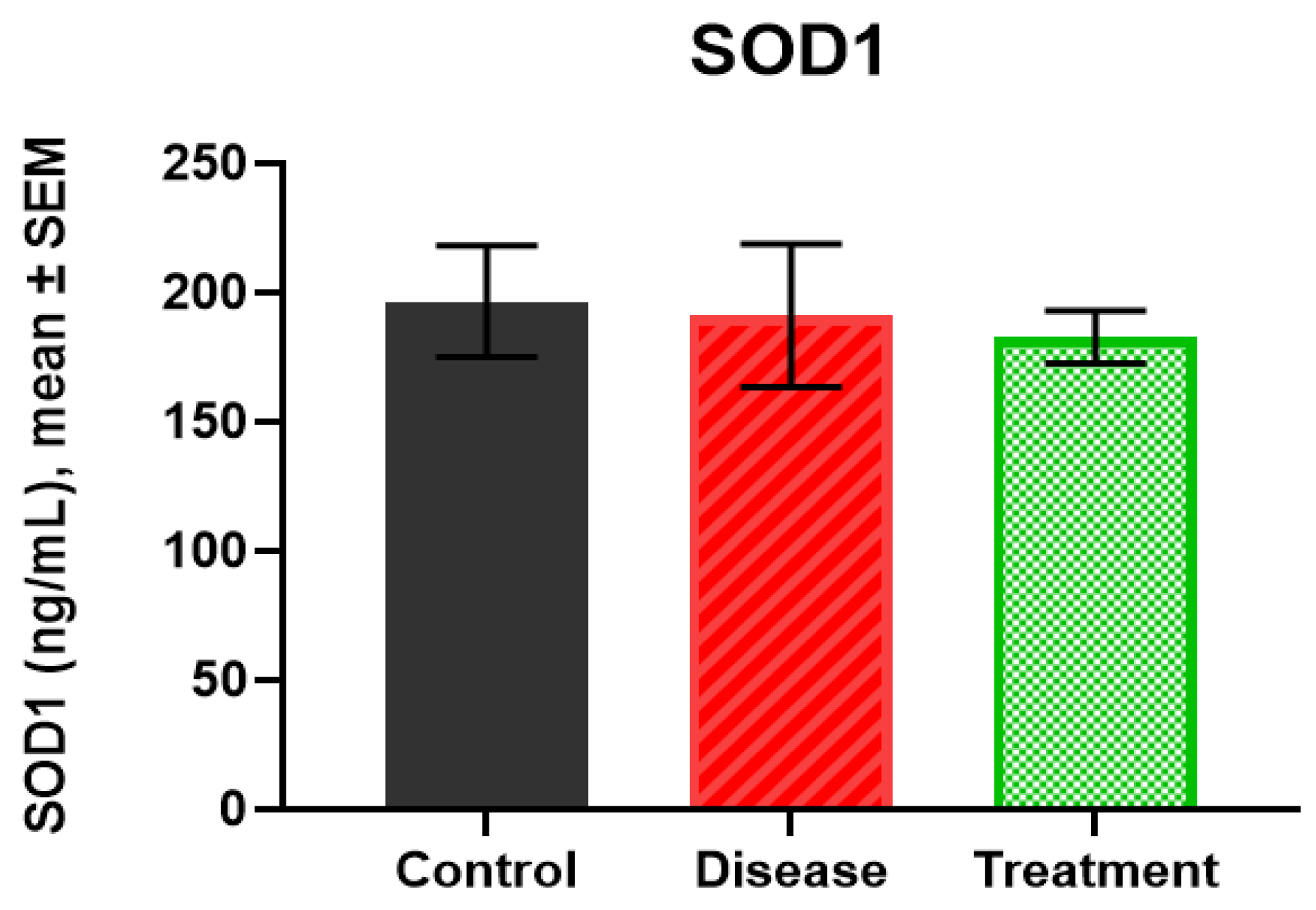

2.4. SOD1 Levels

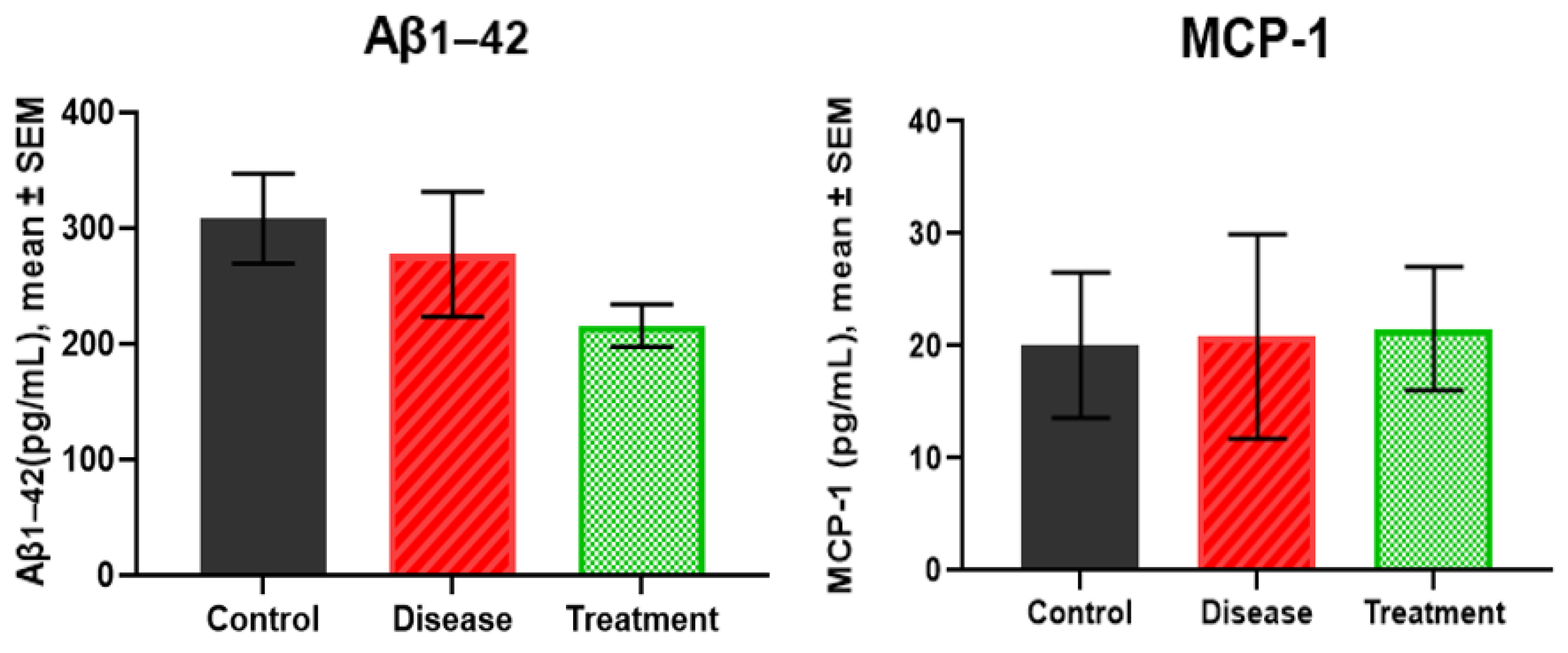

2.5. Serum Levels of Aβ1-42 and MCP-1

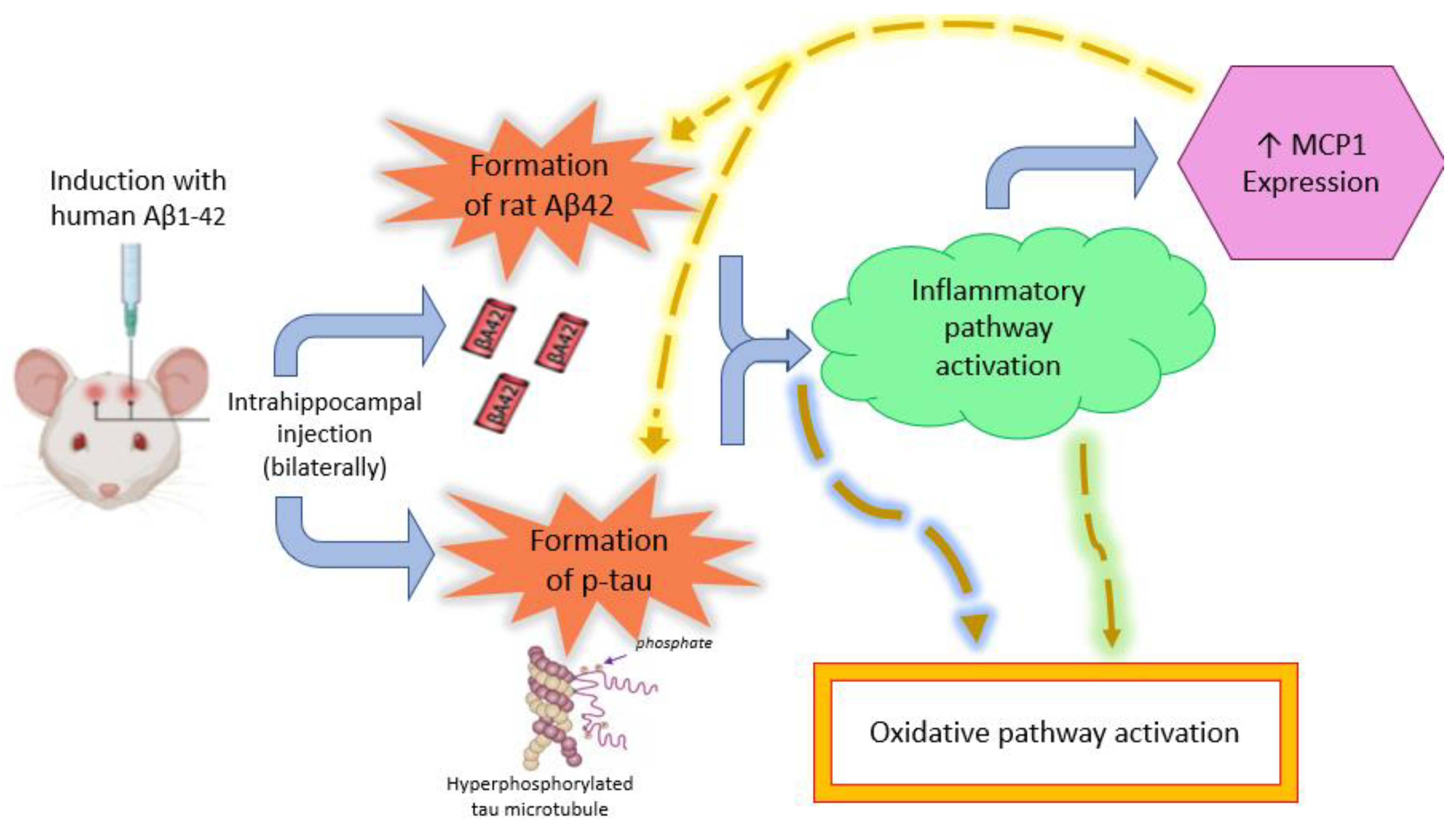

3. Discussion

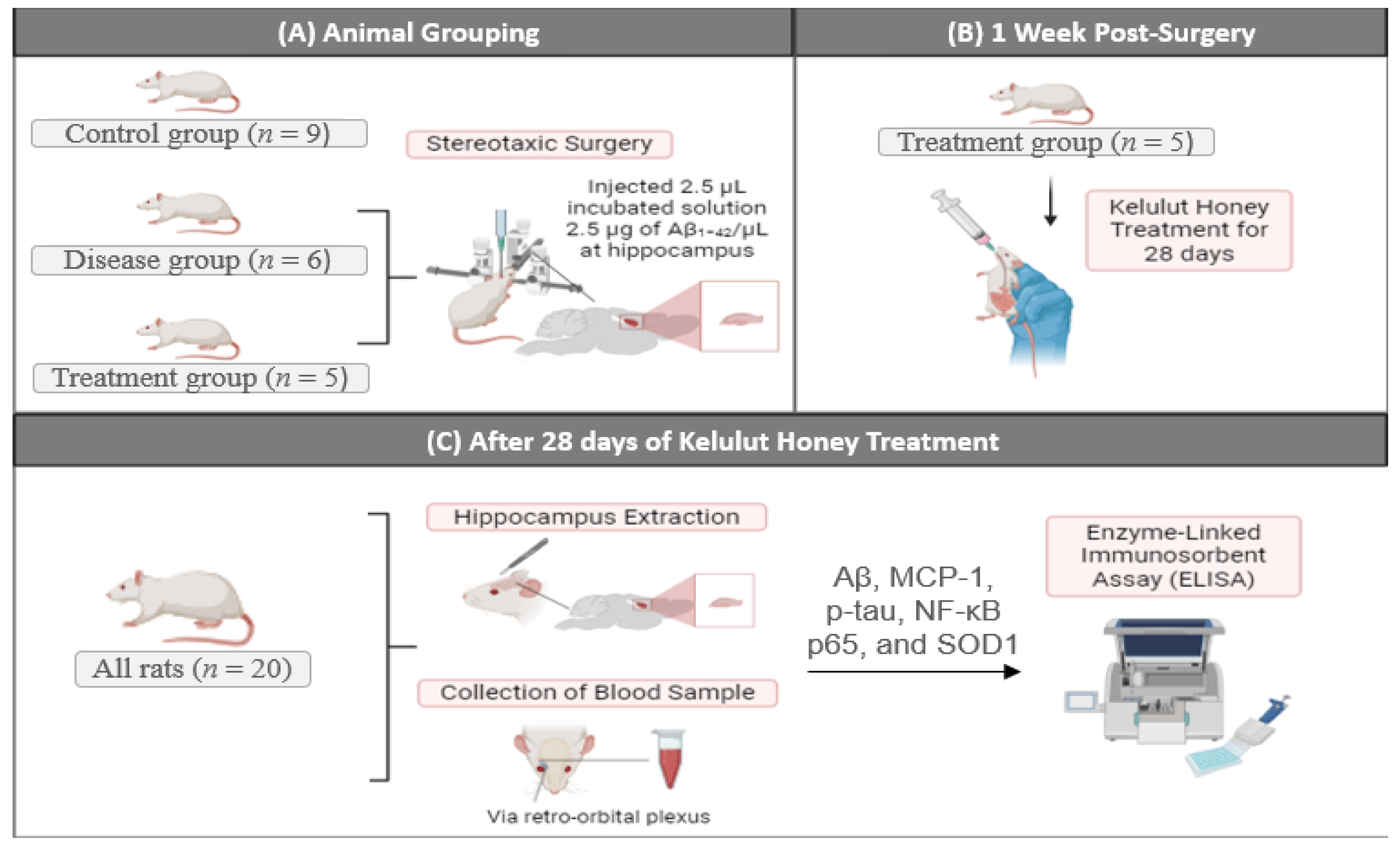

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Model and Experimental Design

4.2. Amyloid β1-42 Peptide Incubation

4.3. Stereotaxic Surgery

4.4. Kelulut Honey Treatment

4.5. Blood Collection and Brain Sectioning for ELISA Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 |

| NF-κB p65 | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B cells p65 subunit |

| SOD1 | Superoxide Dismutase 1 |

| Aβ | Amyloid Beta |

| p-tau | Phosphorylated Tau |

| p-tau217 | Phosphorylated Tau at threonine 217 |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 Beta |

| CDK5 | Cyclin-Dependent Kinase 5 |

| NfL | Neurofilament Light chain |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| UKM | Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia |

| UKMAEC | Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Research and Animal Ethics Committee |

| dH2O | Distilled Water |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| BBM | Blood-Based Biomarker |

References

- 2024 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, A.V.; Kutuzova, A.D.; Kuzmichev, I.A.; Abakumov, M.A. Alzheimer’s Disease: From Molecular Mechanisms to Promising Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piura, Y.D.; Figdore, D.J.; Lachner, C.; Bornhorst, J.; Algeciras-Schimnich, A.; Graff-Radford, N.R.; Day, G.S. Diagnostic performance of plasma p-tau217 and Aβ42/40 biomarkers in the outpatient memory clinic. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e70316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom-Cadena, M.; Davies, C.; Sirisi, S.; Lee, J.E.; Simzer, E.M.; Tzioras, M.; Querol-Vilaseca, M.; Sánchez-Aced, É.; Chang, Y.Y.; Holt, K.; et al. Synaptic oligomeric tau in Alzheimer’s disease—A potential culprit in the spread of tau pathology through the brain. Neuron 2023, 111, 2170–2183.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Shepardson, N.; Yang, T.; Chen, G.; Walsh, D.; Selkoe, D.J. Soluble amyloid beta-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 5819–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Zhou, W.; Liu, S.; Deng, Y.; Cai, F.; Tone, M.; Tong, Y.; Song, W. Increased NF-κB signalling up-regulates BACE1 expression and its therapeutic potential in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 15, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janelsins, M.C.; Mastrangelo, M.A.; Oddo, S.; LaFerla, F.M.; Federoff, H.J.; Bowers, W.J. Early correlation of microglial activation with enhanced tumor necrosis factor-alpha and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression specifically within the entorhinal cortex of triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice. J. Neuroinflamm. 2005, 2, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Zhou, C.; Yan, J.; Guo, C.; Dong, W. Activation of the IL-17/TRAF6/NF-κB pathway is implicated in Aβ-induced neurotoxicity. BMC Neurosci. 2023, 24, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Murata, N.; Noda, Y.; Tahara, S.; Kaneko, T.; Kinoshita, N.; Hatsuta, H.; Murayama, S.; Barnham, K.J.; Irie, K.; et al. SOD1 (copper/zinc superoxide dismutase) deficiency drives amyloid β protein oligomerization and memory loss in mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 44557–44568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, G.; Valletta, M.; Rizzuto, D.; Xia, X.; Qiu, C.; Orsini, N.; Dale, M.; Andersson, S.; Fredolini, C.; Winblad, B.; et al. Blood-based biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease and incident dementia in the community. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2027–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.; Ahmad, F.; Teoh, S.L.; Kumar, J.; Yahaya, M.F. Unveiling the Therapeutic Potential of Kelulut (Stingless Bee) Honey in Alzheimer’s Disease: Findings from a Rat Model Study. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shajahan, S.R.; Muhammad, H.; Mustafa, M.Z.; Kumari, Y.; Jazuli, I.; Zulkapli, A.; Sk, N.; Hamdan, A.N.A.; Wahid, N.S.; Ramli, M.D.C. Role of stingless bee honey in ameliorating cognitive dysfunction in an aluminium chloride and D-galactose induced Alzheimer’s disease model in rats. Nat. Life Sci. Commun. 2025, 24, E2025053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, N.A.; Hassan, Z.; Mustafa, M.Z.; Azman, W.N.W.; Hadie, S.N.H.; Ghani, N.; Mat Zin, A.A. The potential neuroprotective effects of stingless bee honey. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 14, 1048028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Hortal, M.D.; Romero-Márquez, J.M.; Ansary, J.; Hinojosa-Nogueira, D.; Montalbán-Hernández, C.; Varela-López, A.; Quiles, J.L. Honey as a Neuroprotective Agent: Molecular Perspectives on Its Role in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.; Ahmad, F.; Teoh, S.L.; Kumar, J.; Yahaya, M.F. Honey and Alzheimer's Disease-Current Understanding and Future Prospects. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekov, S.I.; Ivanov, D.G.; Bugrova, A.E.; Indeykina, M.I.; Zakharova, N.V.; Popov, I.A.; Kononikhin, A.S.; Kozin, S.A.; Makarov, A.A.; Nikolaev, E.N. Evaluation of MALDI-TOF/TOF Mass Spectrometry Approach for Quantitative Determination of Aspartate Residue Isomerization in the Amyloid-β Peptide. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2019, 30, 1325–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Yamaguchi, T.; Fukunaga, S.; Okada, Y.; Yano, Y.; Hoshino, M.; Matsuzaki, K. Comparison between the aggregation of human and rodent amyloid β-proteins in GM1 ganglioside clusters. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 7523–7530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.W.; Wong, G.T.C.; Lim, G.; McCabe, M.F.; Wang, S.; Irwin, M.G.; Mao, J. Peripheral nerve injury alters the expression of NF-κB in the rat’s hippocampus. Brain Res. 2011, 1378, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.G.; Zhao, X.L.; Xu, W.C.; Zhao, X.J.; Wang, J.N.; Lin, X.W.; Sun, T.; Fu, Z. Activation of spinal NF-κB/p65 contributes to peripheral inflammation and hyperalgesia in rat adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazia, T.; Nova, A.; Gentilini, D.; Beecham, A.; Piras, M.; Saddi, V.; Ticca, A.; Bitti, P.; McCauley, J.L.; Berzuini, C.; et al. Investigating the Causal Effect of Brain Expression of CCL2, NFKB1, MAPK14, TNFRSF1A, CXCL10 Genes on Multiple Sclerosis: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Approach. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 516862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Yuan, K.; Wu, P.; Xu, C.; Ji, Z.; Xu, W.; Yu, H.; Xu, A.; Liu, Y.; et al. Bindarit attenuates neuroinflammation after subarachnoid hemorrhage by regulating the CCL2/CCR2/NF-κB pathway. Brain Res. Bull. 2025, 220, 111183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joly-Amado, A.; Hunter, J.; Quadri, Z.; Zamudio, F.; Rocha-Rangel, P.V.; Chan, D.; Kesarwani, A.; Nash, K.; Lee, D.C.; Morgan, D.; et al. CCL2 Overexpression in the Brain Promotes Glial Activation and Accelerates Tau Pathology in a Mouse Model of Tauopathy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida, H.; Sahar, M.; Nikdouz, A.; Arezoo, H. Chemokines in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2025, 103, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Horiba, M.; Buescher, J.L.; Huang, D.; Gendelman, H.E.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Ikezu, T. Overexpression of monocyte chemotactic protein-1/CCL2 in β-amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice show accelerated diffuse β-amyloid deposition. Am. J. Pathol. 2005, 166, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.L.; Ganaraja, B.; Marathe, A.; Manjrekar, P.A.; Joy, T.; Ullal, S.; Pai, M.M.; Murlimanju, B.V. Comparison of malondialdehyde levels and superoxide dismutase activity in resveratrol and resveratrol/donepezil combination treatment groups in Alzheimer’s disease induced rat model. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo-Flores Guzmán, B.; Elizabeth Chaffey, T.; Hansika Palpagama, T.; Waters, S.; Boix, J.; Tate, W.P.; Peppercorn, K.; Dragunow, M.; Waldvogel, H.J.; Faull, R.L.M.; et al. The Interplay Between Beta-Amyloid 1-42 (Aβ1-42)-Induced Hippocampal Inflammatory Response, p-tau, Vascular Pathology, and Their Synergistic Contributions to Neuronal Death and Behavioral Deficits. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 522073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, M.; Kang, M.H.; Park, T.J.; Ali, J.; Choe, K.; Park, J.S.; Kim, M.O. Multifaceted neuroprotective approach of Trolox in Alzheimer’s disease mouse model: Targeting Aβ pathology, neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and synaptic dysfunction. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1453038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, R.; Duran-Aniotz, C.; Castilla, J.; Estrada, L.D.; Soto, C. De novo induction of amyloid-β deposition in vivo. Mol. Psychiatry 2012, 17, 1347–1353, Erratum in Mol. Psychiatry 2012, 17, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wei, W.; Zhao, M.; Ma, L.; Jiang, X.; Pei, H.; Cao, Y.; Li, H. Interaction between Aβ and Tau in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 2181–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: Mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Qi, X.-L.; Cao, Y.; Yu, W.-F.; Ravid, R.; Winblad, B.; Pei, J.-J.; Guan, Z.-Z. Elevations in the Levels of NF-κB and Inflammatory Chemotactic Factors in the Brains with Alzheimer’s Disease—One Mechanism May Involve α3 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016, 13, 1290–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Jana, M.; Paidi, R.K.; Majumder, M.; Raha, S.; Dasarathy, S.; Pahan, K. Tau fibrils induce glial inflammation and neuropathology via TLR2 in Alzheimer’s disease-related mouse models. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husna Ibrahim, N.; Yahaya, M.F.; Mohamed, W.; Teoh, S.L.; Hui, C.K.; Kumar, J. Pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer’s disease: Seeking clarity in a time of uncertainty. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickman, A.M.; Manly, J.J.; Honig, L.S.; Sanchez, D.; Reyes-Dumeyer, D.; Lantigua, R.A.; Lao, P.J.; Stern, Y.; Vonsattel, J.P.; Teich, A.F.; et al. Plasma p-tau181, p-tau217, and other blood-based Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in a multi-ethnic, community study. Alzheimers Dement. 2021, 17, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamagno, E.; Guglielmotto, M.; Vasciaveo, V.; Tabaton, M. Oxidative Stress and Beta Amyloid in Alzheimer's Disease. Which Comes First: The Chicken or the Egg? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shaikh, A.; Ahmad, F.; Kumar, J.; Teoh, S.L.; Yahaya, M.F. Early Molecular Biomarkers in an Amyloid-β-Induced Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: Effects of Kelulut Honey. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021059

Shaikh A, Ahmad F, Kumar J, Teoh SL, Yahaya MF. Early Molecular Biomarkers in an Amyloid-β-Induced Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: Effects of Kelulut Honey. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021059

Chicago/Turabian StyleShaikh, Ammara, Fairus Ahmad, Jaya Kumar, Seong Lin Teoh, and Mohamad Fairuz Yahaya. 2026. "Early Molecular Biomarkers in an Amyloid-β-Induced Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: Effects of Kelulut Honey" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021059

APA StyleShaikh, A., Ahmad, F., Kumar, J., Teoh, S. L., & Yahaya, M. F. (2026). Early Molecular Biomarkers in an Amyloid-β-Induced Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: Effects of Kelulut Honey. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021059