In Silico Design and Characterization of a Rationally Engineered Cas12j2 Gene Editing System for the Treatment of HPV-Associated Cancers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

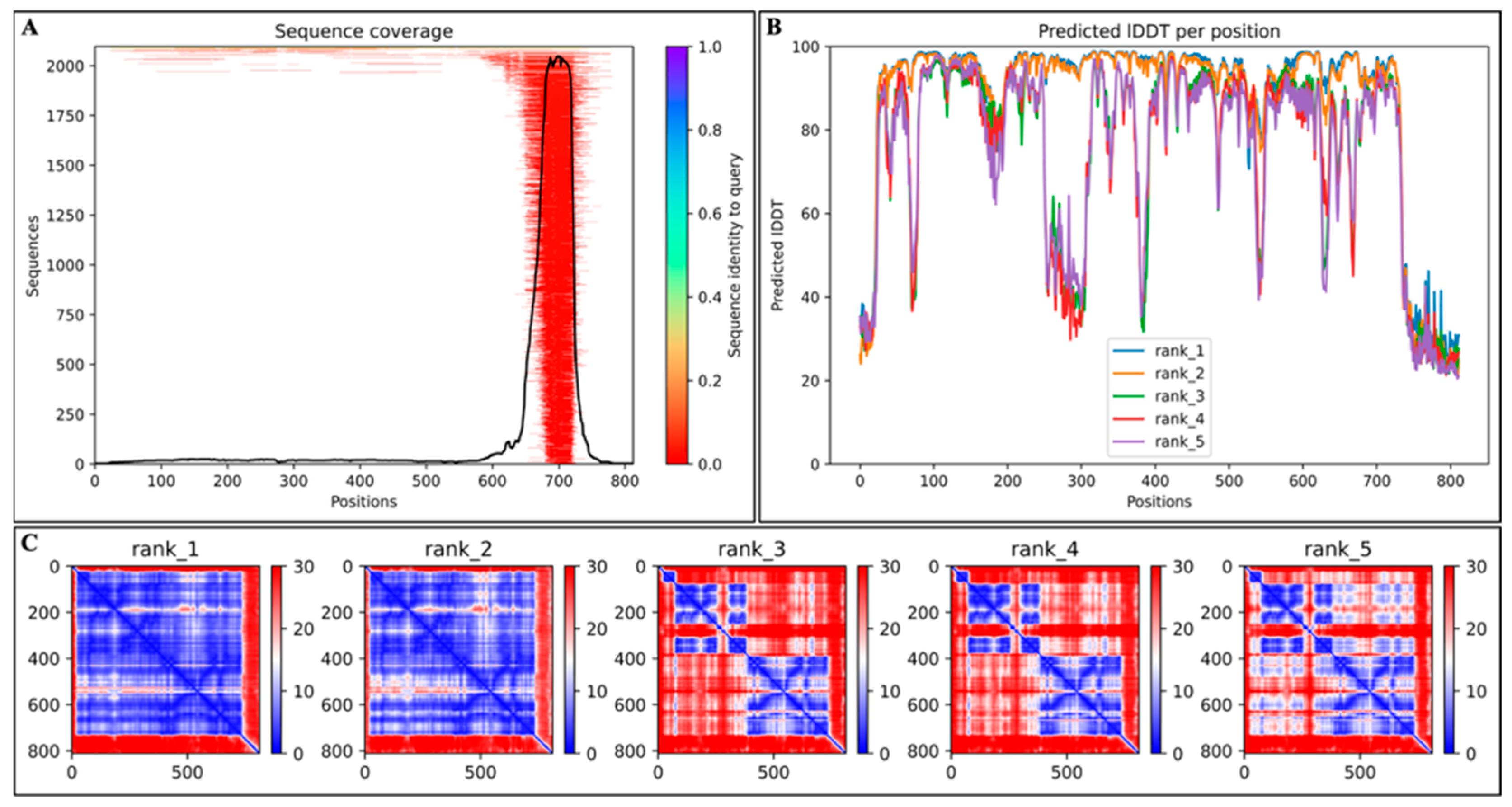

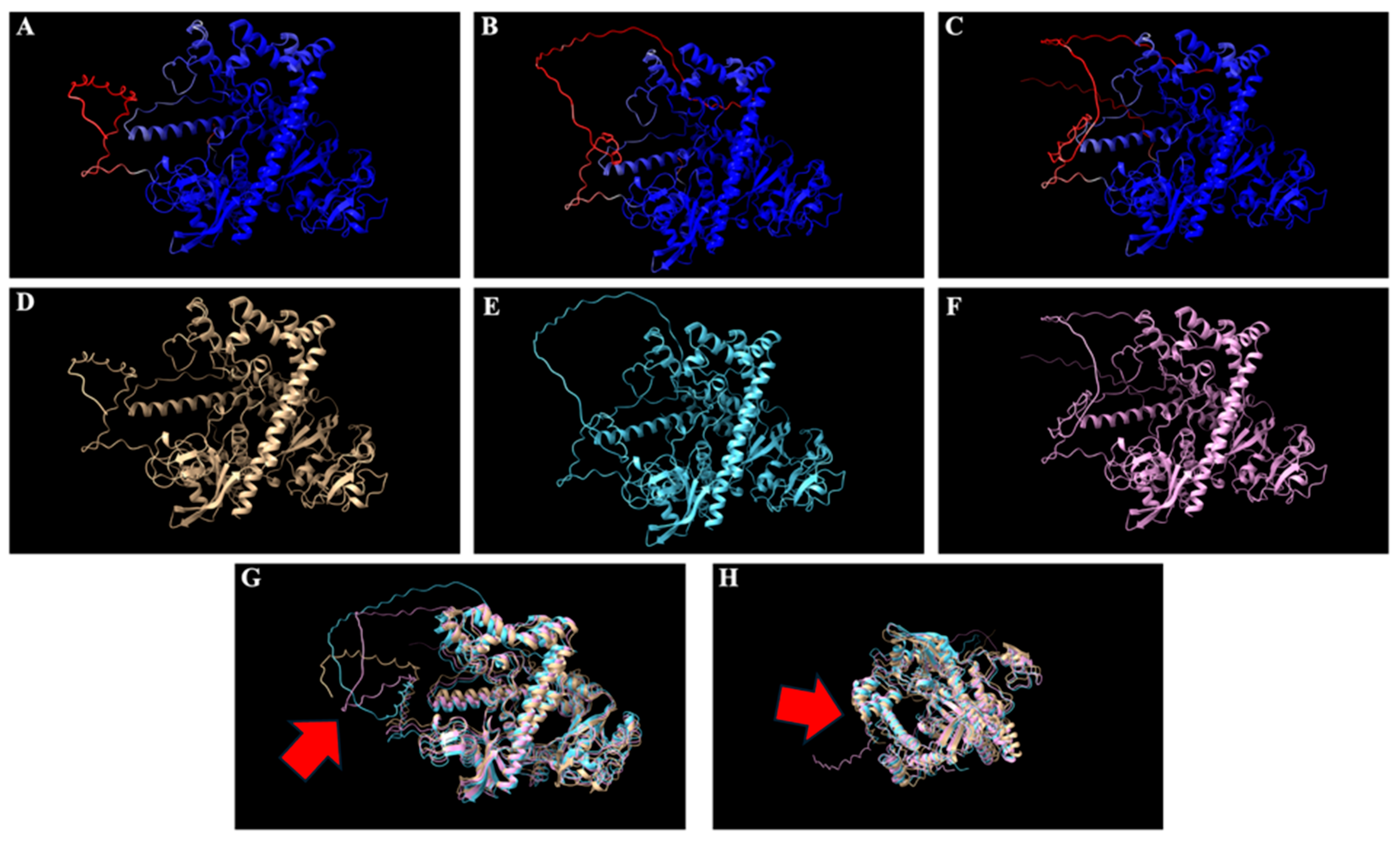

2.1. Results for Structural Modeling of Cas12j2 Variants

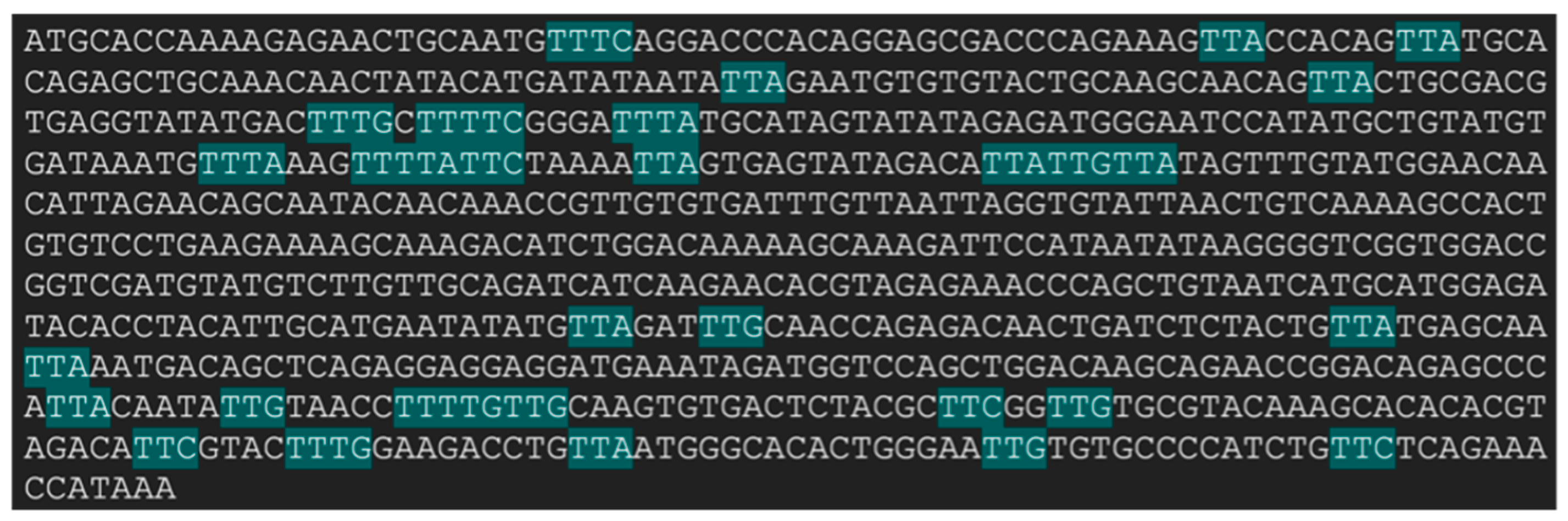

2.2. gRNA Candidate Design and Off-Target Analysis

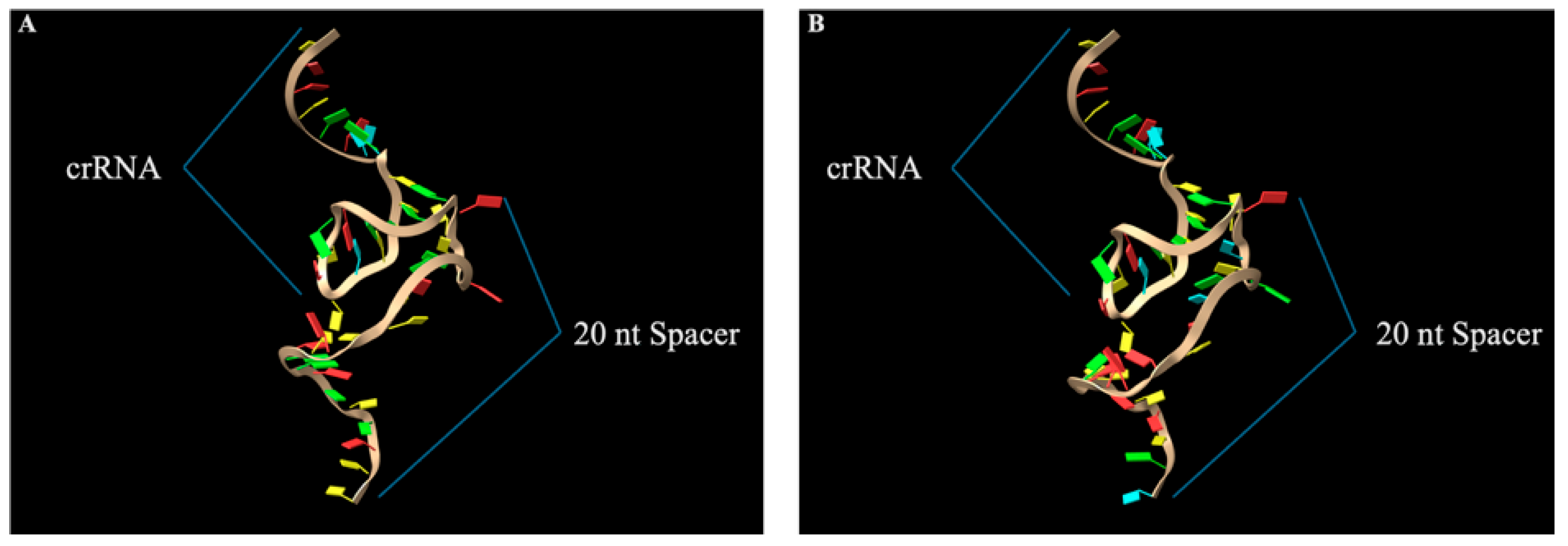

2.3. Structural Modeling of gRNAs

2.4. Protein-RNA Docking Analysis

2.5. Molecular Dynamics of Cas12j2-gRNA Complexes Using Amber

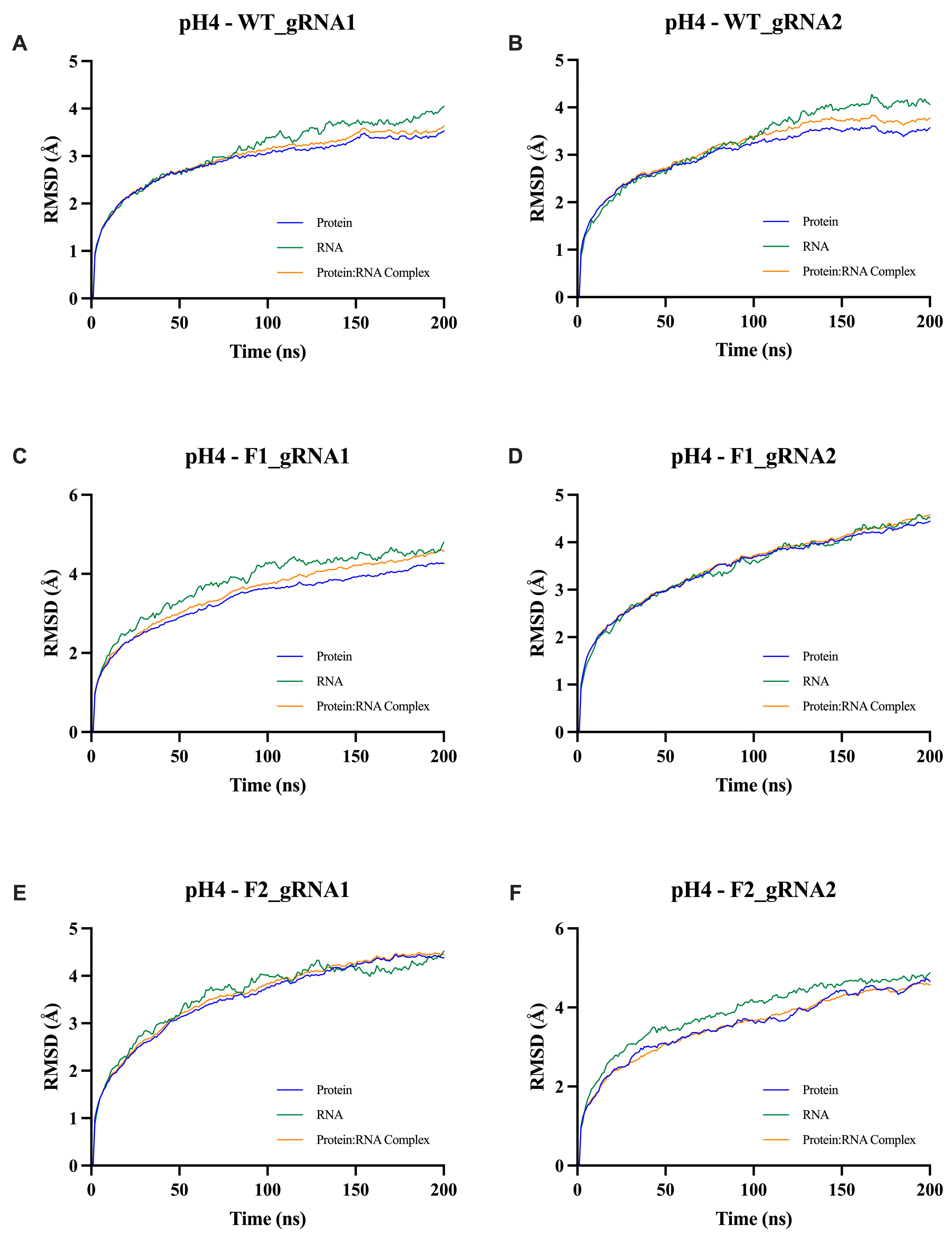

2.5.1. Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) Analysis

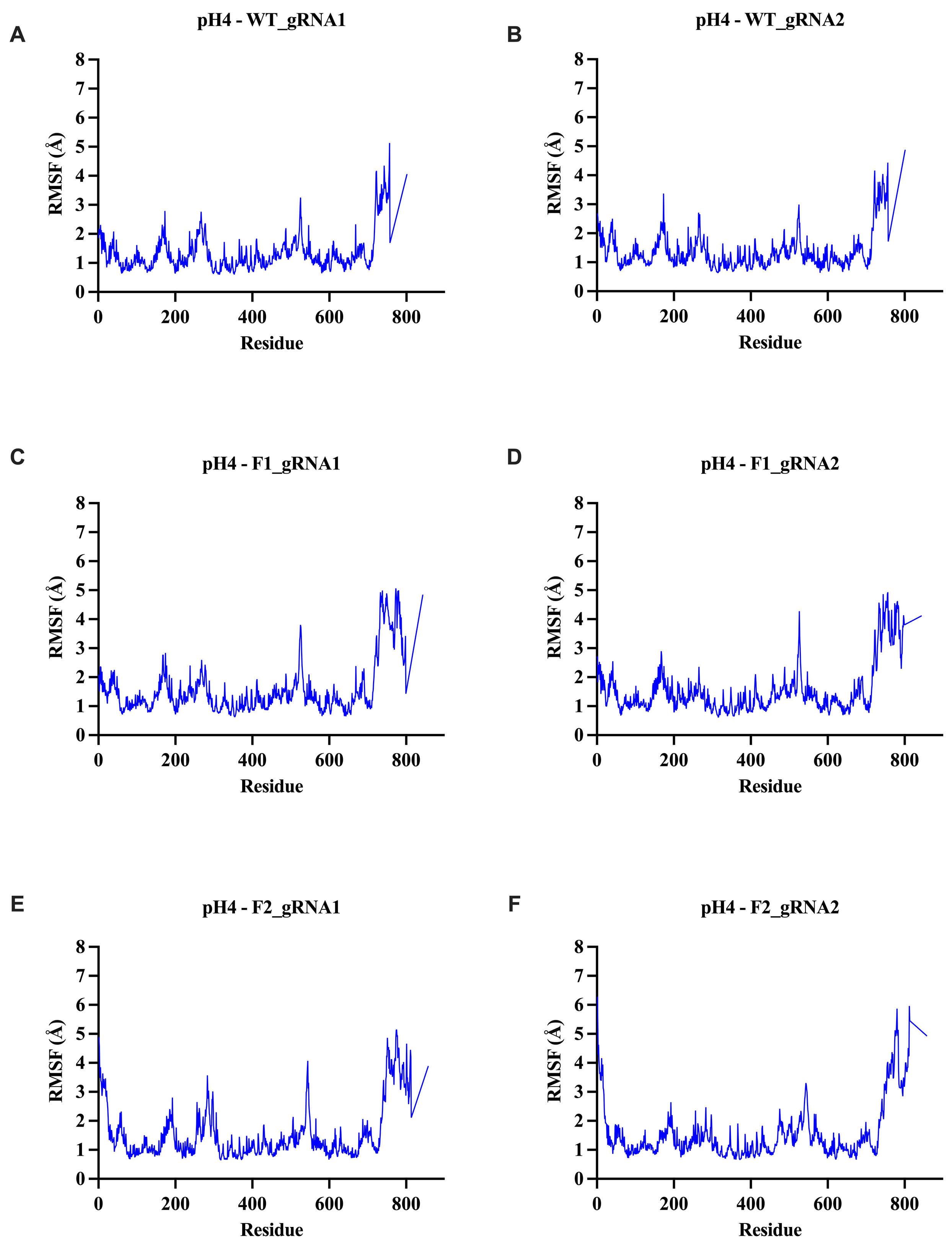

2.5.2. Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) Analysis

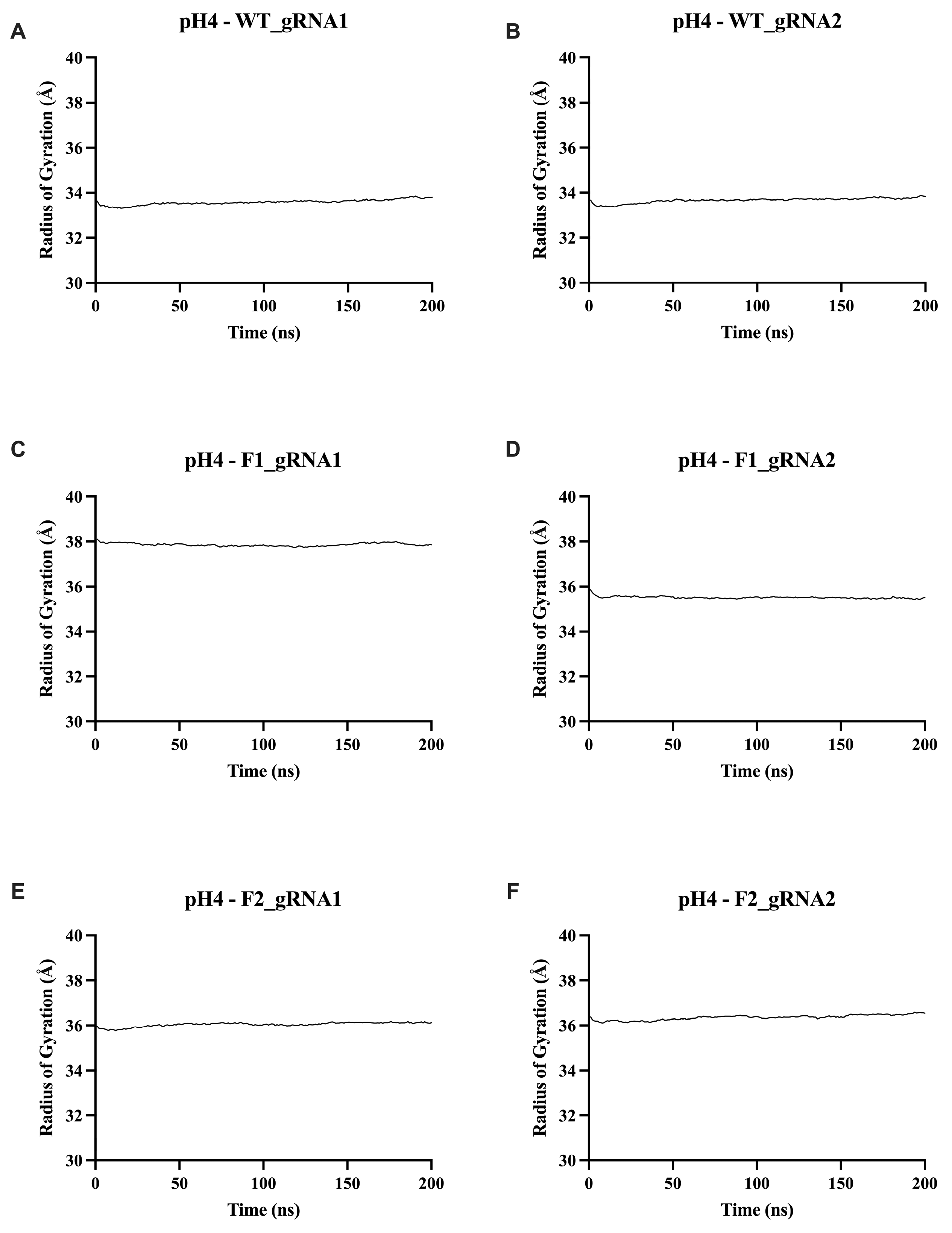

2.5.3. Radius of Gyration (Rg) Analysis

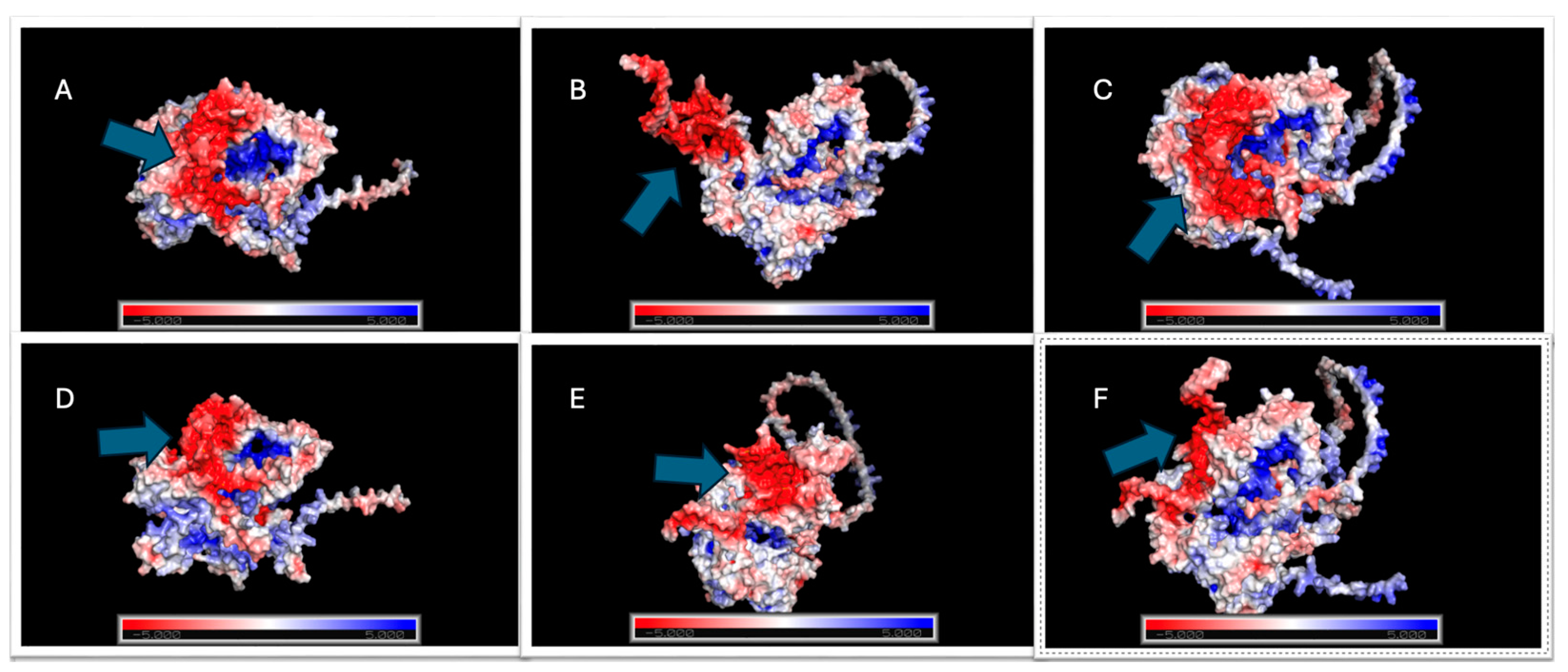

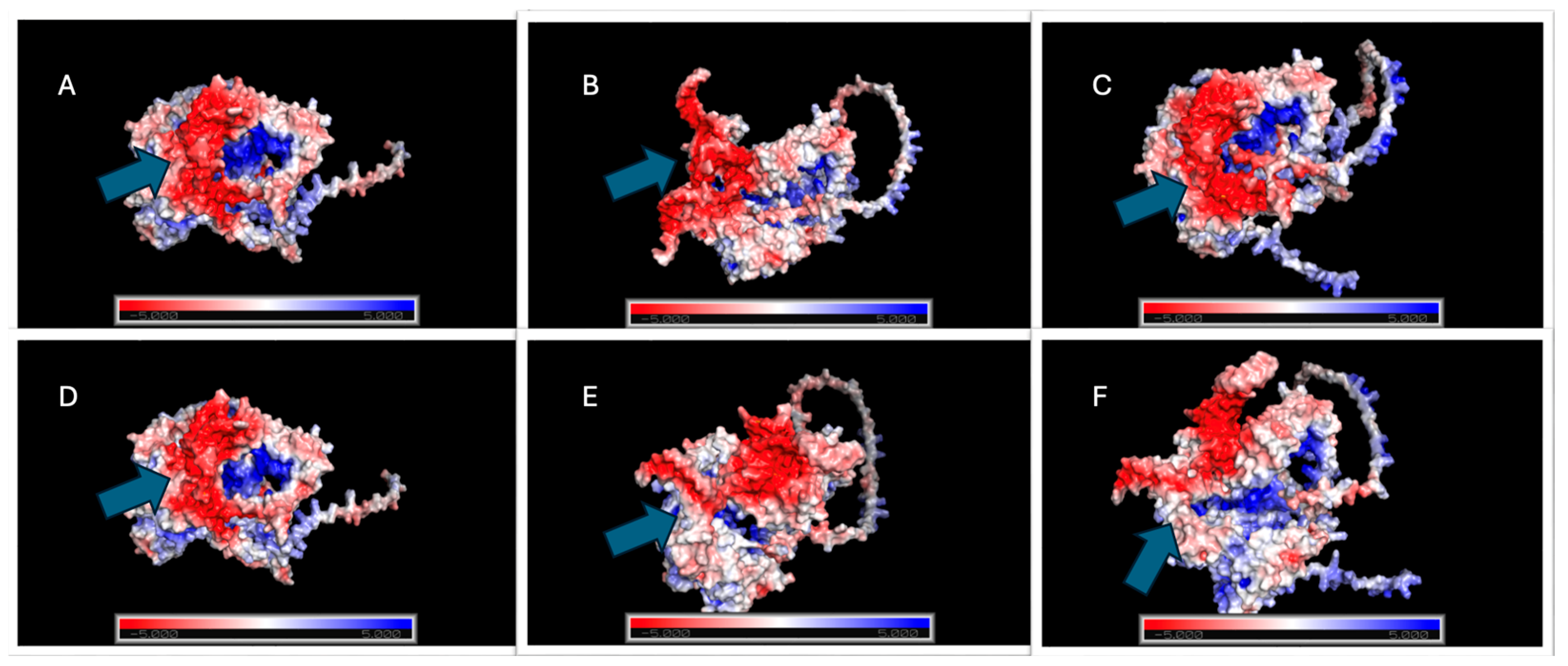

2.5.4. Electrostatic Profile Analysis

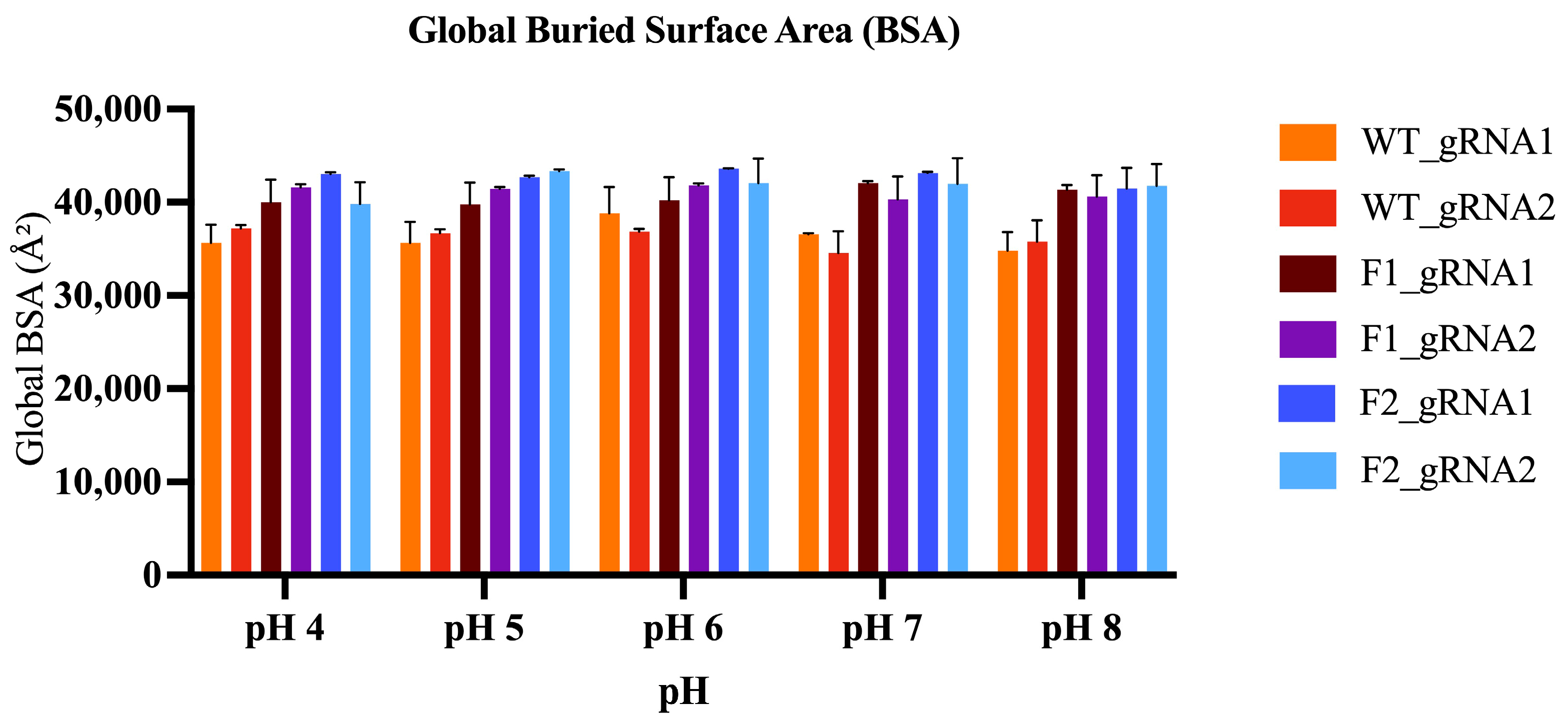

2.5.5. Buried Surface Area

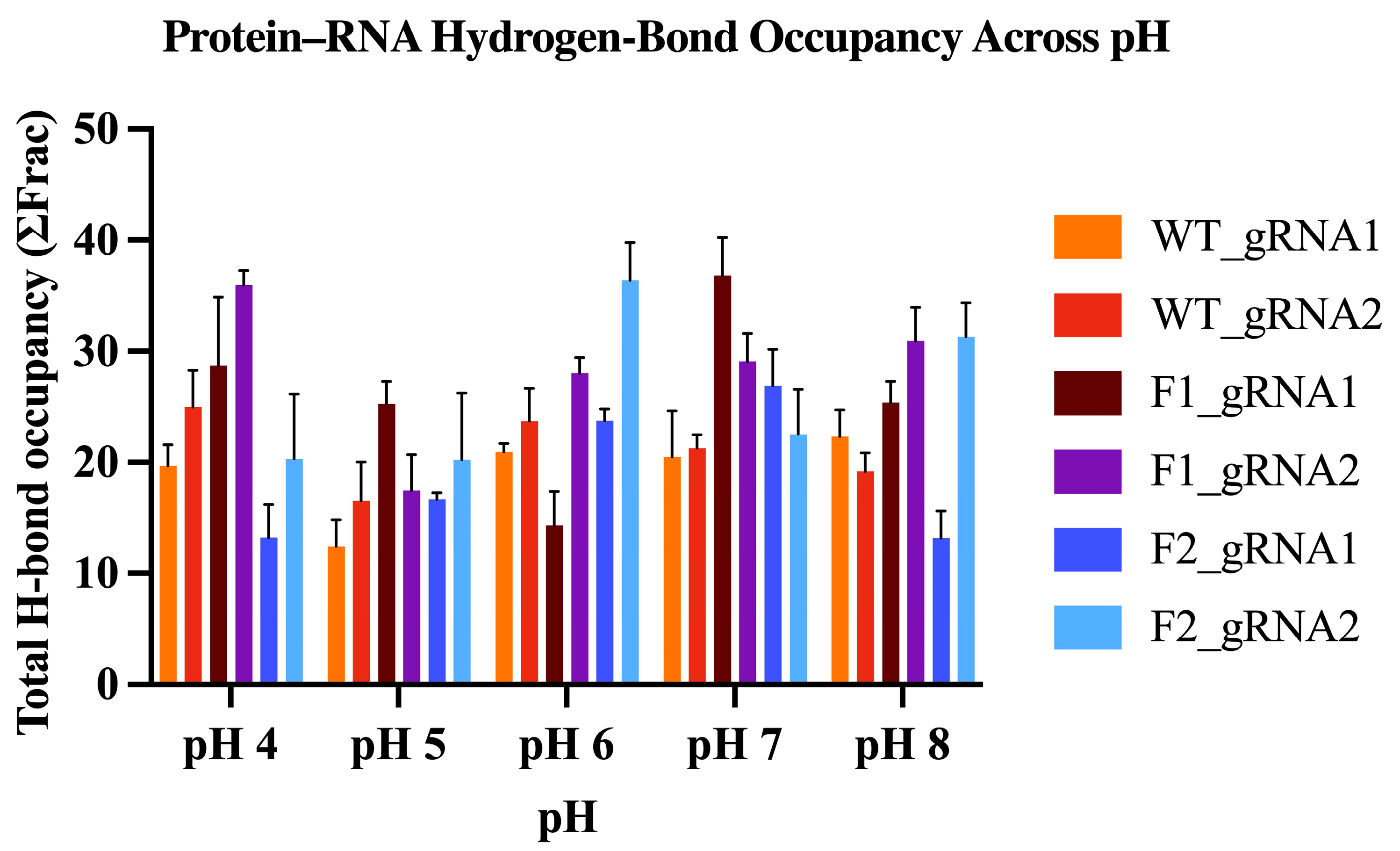

2.5.6. Hydrogen-Bond Occupancy Analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. Rational Design of a Dual gRNA Cas12j2 Gene Editing System

3.2. Structure Guided Engineering

3.3. Off-Target Predictions

3.4. Docking and MD Stability of Cas12j2-gRNA Complexes

3.5. Therapeutic Potential in HPV-Associated Cancers

3.6. Limitations and Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cas12j2 Sequence Retrieval and Variant Design

4.2. Design and Selection of Candidate gRNAs

4.3. Off-Target Analysis of Potential gRNA Candidates

4.4. Approach to Structural Modeling of Cas12j2 Variants

4.5. Protein-RNA Docking

4.6. Molecular Dynamic Simulations of Cas12j2-gRNA Complexes in Intracellular Conditions

4.7. Trajectory Analysis

4.8. Electrostatic Surface Mapping and Solvent Accessible Surface Area Analysis

4.9. Design and Production of Expression Vector

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adekanmbi, V.; Guo, F.; Hsu, C.D.; Shan, Y.; Kuo, Y.-F.; Berenson, A.B. Incomplete HPV Vaccination among Individuals Aged 27–45 Years in the United States: A Mixed-Effect Analysis of Individual and Contextual Factors. Vaccines 2023, 11, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairkhah, N.; Bolhassani, A.; Najafipour, R. Current and future direction in treatment of HPV-related cervical disease. J. Mol. Med. 2022, 100, 829–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynarczyk-Bonikowska, B.; Rudnicka, L. HPV Infections—Classification, Pathogenesis, and Potential New Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.K.; Alblooshi, S.S.E.; Yaqoob, R.; Behl, S.; Al Saleem, M.; Rakha, E.A.; Malik, F.; Singh, M.; Macha, M.A.; Akhtar, M.K.; et al. Human papilloma virus (HPV) mediated cancers: An insightful update. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qiu, K.; Ren, J.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, P. Roles of human papillomavirus in cancers: Oncogenic mechanisms and clinical use. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.C.; Wakeham, K.; Langley, R.E.; Vale, C.L. Increased risk of second cancers at sites associated with HPV after a prior HPV-associated malignancy, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 120, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Yang, B.; Yin, H.; Chen, J.; Ma, W.; Xu, Z.; Shen, Y. Global Burden and Incidence Trends in Cancers Associated with Human Papillomavirus Infection: A Population-Based Systematic Study. Pathogens 2025, 14, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E.M.; Kornepati, A.V.R.; Goldstein, M.; Bogerd, H.P.; Poling, B.C.; Whisnant, A.W.; Kastan, M.B.; Cullen, B.R. Inactivation of the Human Papillomavirus E6 or E7 Gene in Cervical Carcinoma Cells by Using a Bacterial CRISPR/Cas RNA-Guided Endonuclease. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 11965–11972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, K.; Dou, Y.; Yang, N.; Deng, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, C.; Jiang, L.; Deng, Q.; et al. Genome editing mRNA nanotherapies inhibit cervical cancer progression and regulate the immunosuppressive microenvironment for adoptive T-cell therapy. J. Control. Release 2023, 360, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Yu, L.; Zhu, D.; Ding, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Jiang, X.; Shen, H.; He, D.; et al. Disruption of HPV16-E7 by CRISPR/Cas System Induces Apoptosis and Growth Inhibition in HPV16 Positive Human Cervical Cancer Cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 612823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S.; Hua, L.; Takahashi, Y.; Narita, S.; Liu, Y.-H.; Li, Y. In vitro and in vivo growth suppression of human papillomavirus 16-positive cervical cancer cells by CRISPR/Cas9. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 1422–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubair, L.; Fallaha, S.; McMillan, N.A. Systemic Delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 Targeting HPV Oncogenes Is Effective at Eliminating Established Tumors. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 2091–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaj, T.; Gersbach, C.A.; Barbas, C.F., III. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2014, 31, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabali, A.A.; El-Tanani, M.; Tambuwala, M.M. Principles of CRISPR-Cas9 technology: Advancements in genome editing and emerging trends in drug delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 92, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Z. CRISPR-Cas systems: Overview, innovations and applications in human disease research and gene therapy. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2401–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.D.; Lander, E.S.; Zhang, F. Development and Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Engineering. Cell 2014, 157, 1262–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, F.; Rudin, C.M.; Sen, T. CRISPR Gene Therapy: Applications, Limitations, and Implications for the Future. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danchin, A. In vivo, in vitro and in silico: An open space for the development of microbe-based applications of synthetic biology. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 15, 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzadeh, A.; Kobakhidze, G.; Vuillemot, R.; Jonic, S.; Rouiller, I. In silico prediction, characterization, docking studies and molecular dynamics simulation of human p97 in complex with p37 cofactor. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebrian-Serrano, A.; Davies, B. CRISPR-Cas orthologues and variants: Optimizing the repertoire, specificity and delivery of genome engineering tools. Mamm. Genome 2017, 28, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausch, P.; Al-Shayeb, B.; Bisom-Rapp, E.; Tsuchida, C.A.; Li, Z.; Cress, B.F.; Knott, G.J.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Banfield, J.F.; Doudna, J.A. CRISPR-CasΦ from huge phages is a hypercompact genome editor. Science 2020, 369, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Zhang, F.; Ding, Y. CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery System Engineering for Genome Editing in Therapeutic Applications. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, T.; Mizuta, H.; Sakai, E.; Sakurai, F.; Mizuguchi, H. Evaluation of the correlation between nuclear localization levels and genome editing efficiencies of Cas12a fused with nuclear localization signals. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 114, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, Q.; Wang, J.; Nie, Y.; Fang, C.; Liang, W. Research Progress and Application of Miniature CRISPR-Cas12 System in Gene Editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.L.; Caodaglio, A.S.; Sichero, L. Regulation of HPV transcription. Clinics 2018, 73, e486s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.; Guidry, J.; Scott, M.; Zwolinska, K.; Raikhy, G.; Prasai, K.; Bienkowska-Haba, M.; Bodily, J.; Sapp, M.; Scott, R. Detecting episomal or integrated human papillomavirus 16 DNA using an exonuclease V-qPCR-based assay. Virology 2019, 537, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Teng, A.; Hu, G.; Wuyun, Q.; Zheng, W. The Historical Evolution and Significance of Multiple Sequence Alignment in Molecular Structure and Function Prediction. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Ma, X.; Gao, F.; Guo, Y. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1143157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manghwar, H.; Li, B.; Ding, X.; Hussain, A.; Lindsey, K.; Zhang, X.; Jin, S. CRISPR/Cas Systems in Genome Editing: Methodologies and Tools for sgRNA Design, Off-Target Evaluation, and Strategies to Mitigate Off-Target Effects. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, A.; Wen, J.; Kim, P.; Song, Q.; Zhou, X. CRISPRoffT: Comprehensive database of CRISPR/Cas off-targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D914–D924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Guo, J.; Liu, J. CRISPR-M: Predicting sgRNA off-target effect using a multi-view deep learning network. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1011972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.; Prasad, M.K. Beyond the promise: Evaluating and mitigating off-target effects in CRISPR gene editing for safer therapeutics. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 11, 1339189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Park, J.; Kim, J.S. Cas-OFFinder: A fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1473–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, D.; Chakravarti, R.; Bhattacharjee, O.; Majumder, S.; Chaudhuri, D.; Ahmed, K.T.; Roy, D.; Bhattacharya, B.; Arya, M.; Gautam, A.; et al. A mechanistic study on the tolerance of PAM distal end mismatch by SpCas9. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakos, V.; Nentidis, A.; Krithara, A.; Paliouras, G. CRISPR–Cas9 gRNA efficiency prediction: An overview of predictive tools and the role of deep learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 3616–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Zhu, C.; Chen, X.; Yan, J.; Xue, D.; Wei, Z.; Chuai, G.; Liu, Q. Systematic Exploration of Optimized Base Editing gRNA Design and Pleiotropic Effects with BExplorer. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 21, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeussler, M.; Schönig, K.; Eckert, H.; Eschstruth, A.; Mianné, J.; Renaud, J.-B.; Schneider-Maunoury, S.; Shkumatava, A.; Teboul, L.; Kent, J.; et al. Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhou, M.; Li, D.; Manthey, J.; Lioutikova, E.; Wang, H.; Zeng, X. Whole genome analysis of CRISPR Cas9 sgRNA off-target homologies via an efficient computational algorithm. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Biesiada, M.; Purzycka, K.J.; Szachniuk, M.; Blazewicz, J.; Adamiak, R.W. Automated RNA 3DStructure Prediction with RNAComposer. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1490, 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Yeon, Y.J.; Park, H.J.; Park, H.-Y.; Yoo, Y.J. Effect of His-tag location on the catalytic activity of 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2014, 19, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzadeh, M.; Poltash, M.L.; Laganowsky, A.; Russell, D.H. Structural Analysis of the Effect of a Dual-FLAG Tag on Transthyretin. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslantas, Y.; Surmeli, N.B. Effects of N-Terminal and C-Terminal Polyhistidine Tag on the Stability and Function of the Thermophilic P450 CYP119. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2019, 2019, 8080697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wu, T.; Zhang, B.; Liu, S.; Song, W.; Qiao, J.; Ruan, H. Types of nuclear localization signals and mechanisms of protein import into the nucleus. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, J. Systematic Investigation of the Effects of Multiple SV40 Nuclear Localization Signal Fusion on the Genome Editing Activity of Purified SpCas9. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, T.; Akuta, T. Beyond Purification: Evolving Roles of Fusion Tags in Biotechnology. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabias, A.; Fuglsang, A.; Temperini, P.; Pape, T.; Sofos, N.; Stella, S.; Erlendsson, S.; Montoya, G. Structure of the mini-RNA-guided endonuclease CRISPR-Cas12j3. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, S.H.; LaFrance, B.; Kaplan, M.; Doudna, J.A. Conformational control of DNA target cleavage by CRISPR–Cas9. Nature 2015, 527, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakravarty, D.; Schafer, J.W.; Chen, E.A.; Thole, J.F.; Ronish, L.A.; Lee, M.; Porter, L.L. AlphaFold predictions of fold-switched conformations are driven by structure memorization. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, A.F.; Herreno-Pachón, A.M.; Benincore-Flórez, E.; Karunathilaka, A.; Tomatsu, S. Current Strategies for Increasing Knock-In Efficiency in CRISPR/Cas9-Based Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.-X.; Zhai, H.; Shi, Y.; Liu, G.; Lowry, J.; Liu, B.; Ryan, É.B.; Yan, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, N.; et al. Efficacy and long-term safety of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in the SOD1-linked mouse models of ALS. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samson, C.; du Rand, A.; Hunt, J.; Whitford, W.; Jacobsen, J.; Sheppard, H. A bioinformatic analysis of gene editing off-target loci altered by common polymorphisms, using ‘PopOff’. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2024, 55, 2440–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Zhao, L.; Diao, K.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Tang, D. A versatile CRISPR/Cas9 system off-target prediction tool using language model. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wan, L.; Ren, J.; Zhang, N.; Zeng, H.; Wei, J.; Tang, M. Improving the Genome Editing Efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 in Melon and Watermelon. Cells 2024, 13, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnautova, Y.A.; Abagyan, R.; Totrov, M. Protein-RNA Docking Using ICM. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 4971–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barik, A.; C, N.; Pilla, S.P.; Bahadur, R.P. Molecular architecture of protein-RNA recognition sites. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2015, 33, 2738–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, G.L.; Andrews, C.W.; Capelli, A.-M.; Clarke, B.; LaLonde, J.; Lambert, M.H.; Lindvall, ⊥.M.; Nevins, N.; Semus, S.F.; Senger, S.; et al. A Critical Assessment of Docking Programs and Scoring Functions. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 49, 5912–5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, M.; Bonvin, A.M. Pushing the limits of what is achievable in protein-DNA docking: Benchmarking HADDOCK’s performance. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 5634–5647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Guo, M.; Wei, H.; Chen, Y. Targeting p53 pathways: Mechanisms, structures and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, X.; Robinson, P.; Nominé, Y.; Masson, M.; Charbonnier, S.; Ramirez-Ramos, J.R.; Deryckere, F.; Travé, G.; Orfanoudakis, G. Proteasomal Degradation of p53 by Human Papillomavirus E6 Oncoprotein Relies on the Structural Integrity of p53 Core Domain. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inturi, R.; Jemth, P. CRISPR/Cas9-based inactivation of human papillomavirus oncogenes E6 or E7 induces senescence in cervical cancer cells. Virology 2021, 562, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, R.; Liu, J.; Fan, W.; Li, R.; Cui, Z.; Jin, Z.; Huang, Z.; Xie, H.; Li, L.; Huang, Z.; et al. Gene knock-out chain reaction enables high disruption efficiency of HPV18 E6/E7 genes in cervical cancer cells. Mol. Ther.—Oncolytics 2021, 24, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, Z.; Shamsara, M.; Valipour, E.; Esfandyari, S.; Ehghaghi, A.; Monfaredan, A.; Azizi, Z.; Motevaseli, E.; Modarressi, M.H. Antiproliferative effects of AAV-delivered CRISPR/Cas9-based degradation of the HPV18-E6 gene in HeLa cells. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, M.; Hou, B.; Zheng, B.; Wang, Z.; Huang, M.; Xu, Y.; Chang, J.; Wang, T. CRISPR/Cas9 nanoeditor of double knockout large fragments of E6 and E7 oncogenes for reversing drugs resistance in cervical cancer. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, O.; Lima, M.C.P.; Clark, C.; Cornillie, S.; Roalstad, S.; Iii, T.E.C. Evaluating the accuracy of the AMBER protein force fields in modeling dihydrofolate reductase structures: Misbalance in the conformational arrangements of the flexible loop domains. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 41, 5946–5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, C.L.; Akhtar, S.; Bajpai, P. In silico protein modeling: Possibilities and limitations. EXCLI J. 2014, 13, 513–515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohr, S.E.; Hu, Y.; Ewen-Campen, B.; Housden, B.E.; Viswanatha, R.; Perrimon, N. CRISPR guide RNA design for research applications. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 3232–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.T.; Bi, X.; Hoang, H.T.T.; Ishizaki, A.; Nguyen, M.T.P.; Nguyen, C.H.; Nguyen, H.P.; Van Pham, T.; Ichimura, H. Human Papillomavirus Genotypes and HPV16 E6/E7 Variants among Patients with Genital Cancers in Vietnam. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 71, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Corsi, G.I.; Anthon, C.; Qu, K.; Pan, X.; Liang, X.; Han, P.; Dong, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhong, J.; et al. Enhancing CRISPR-Cas9 gRNA efficiency prediction by data integration and deep learning. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemmer, M.; Thumberger, T.; Keyer, M.D.S.; Wittbrodt, J.; Mateo, J.L. CCTop: An Intuitive, Flexible and Reliable CRISPR/Cas9 Target Prediction Tool. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124633, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoline, L.M.F.; Lima, A.N.; Krieger, J.E.; Teixeira, S.K. Before and after AlphaFold2: An overview of protein structure prediction. Front. Bioinform. 2023, 3, 1120370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, S.S.; Badshah, Y.; Shabbir, M.; Rafiq, M. Molecular Docking Using Chimera and Autodock Vina Software for Nonbioinformaticians. JMIR Bioinform. Biotechnol. 2020, 1, e14232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agu, P.C.; Afiukwa, C.A.; Orji, O.U.; Ezeh, E.M.; Ofoke, I.H.; Ogbu, C.O.; Ugwuja, E.I.; Aja, P.M. Molecular docking as a tool for the discovery of molecular targets of nutraceuticals in diseases management. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, E.C.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Huang, C.C.; E Ferrin, T. Tools for integrated sequence-structure analysis with UCSF Chimera. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2020, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.; Moustaid-Moussa, N.; Gollahon, L. The Molecular Effects of Dietary Acid Load on Metabolic Disease (The Cellular PasaDoble: The Fast-Paced Dance of pH Regulation). Front. Mol. Med. 2021, 1, 777088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinsky, T.J.; Nielsen, J.E.; McCammon, J.A.; Baker, N.A. PDB2PQR: An automated pipeline for the setup of Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics calculations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, W665–W667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, S.K.; Berner, C.; Kulakova, A.; Schneider, M.; Antes, I.; Winter, G.; Harris, P.; Peters, G.H. Investigation of the pH-dependent aggregation mechanisms of GCSF using low resolution protein characterization techniques and advanced molecular dynamics simulations. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1439–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honorato, R.V.; Trellet, M.E.; Jiménez-García, B.; Schaarschmidt, J.J.; Giulini, M.; Reys, V.; Koukos, P.I.; Rodrigues, J.P.G.L.M.; Karaca, E.; van Zundert, G.C.P.; et al. The HADDOCK2.4 web server for integrative modeling of biomolecular complexes. Nat. Protoc. 2024, 19, 3219–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, D.R.; Brooks, B.R. A protocol for preparing explicitly solvated systems for stable molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 054123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, C. A beginner’s guide to assembling a draft genome and analyzing structural variants with long-read sequencing technologies. STAR Protoc. 2022, 3, 101506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioccolo, S.; Barritt, J.D.; Pollock, N.; Hall, Z.; Babuta, J.; Sridhar, P.; Just, A.; Morgner, N.; Dafforn, T.; Gould, I.; et al. The mycobacterium lipid transporter MmpL3 is dimeric in detergent solution, SMALPs and reconstituted nanodiscs. RSC Chem. Biol. 2024, 5, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltrukevich, H.; Bartos, P. RNA-protein complexes and force field polarizability. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1217506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kührová, P.; Mlýnský, V.; Otyepka, M.; Šponer, J.; Banáš, P. Correction to “Sensitivity of the RNA Structure to Ion Conditions as Probed by Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Common Canonical RNA Duplexes”. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabei, A.; Hognon, C.; Martin, J.; Frezza, E. Dynamics of Protein–RNA Interfaces Using All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 4865–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, Z.; Ren, P. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Protein RNA Complexes by Using an Advanced Electrostatic Model. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 7343–7353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belapure, J.; Sorokina, M.; Kastritis, P.L. IRAA: A statistical tool for investigating a protein–protein interaction interface from multiple structures. Protein Sci. 2022, 32, e4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, A.T.; Craddock, T.J.; Klobukowski, M.; Tuszynski, J. Analysis of the Strength of Interfacial Hydrogen Bonds between Tubulin Dimers Using Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules. Biophys. J. 2014, 107, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alonso, P.; Griera, M.; García-Marín, J.; Rodríguez-Puyol, M.; Alajarín, R.; Vaquero, J.J.; Rodríguez-Puyol, D. Pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxal-5-inium salts and 4,5-dihydropyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoxalines: Synthesis, activity and computational docking for protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2021, 44, 116295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraczkiewicz, R.; Braun, W. Exact and efficient analytical calculation of the accessible surface areas and their gradients for macromolecules. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, E.; Dorr, B.; Woetzel, N.; Staritzbichler, R.; Meiler, J. Solvent accessible surface area approximations for rapid and accurate protein structure prediction. J. Mol. Model. 2009, 15, 1093–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichter, K.M.; Setayesh, T.; Malik, P. Strategies for precise gene edits in mammalian cells. Mol. Ther.—Nucleic Acids 2023, 32, 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Chu, W.; Gill, R.A.; Sang, S.; Shi, Y.; Hu, X.; Yang, Y.; Zaman, Q.U.; Zhang, B. Computational Tools and Resources for CRISPR/Cas Genome Editing. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2022, 21, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| E6 gRNA Candidates | ||||||

| Target Region | Features | gRNA 1 | gRNA 2 | gRNA 3 | gRNA 4 | gRNA 4 |

| 5′ Target | PAM | TTT | TTA | TTA | TTA | TTA |

| 20 nt sequence | CAGGACCCACAGGAGCGACC | CCACAGTTATGCACAGAGC | TGCACAGAGCTGCAAACAAC | GAATGTGTGTACTGCAAGCA | CTGCGACGTGAGGTATATGA | |

| 3′ Target | PAM | TTT | TTA | TTG | TTC | TTT |

| 20 nt sequence | GCAACCAGAGACAACTGATC | AATGACAGCTCAGAGGAGG | TGCGTACAAAGCACACACGT | GTACTTTGGAAGACCTGTTA | GGAAGACCTGTTAATGGGCA | |

| E6 Region 5′-gRNAs Candidates | |||||

| Selection Parameters | gRNA 1 | gRNA 2 | gRNA 3 | gRNA 4 | gRNA 5 |

| PAM Site | TTT | TTA | TTA | TTA | TTA |

| 20-nt Target Sequence | CAGGACCCACAGGAGCGACC | CCACAGTTATGCACAGAGCT | TGCACAGAGCTGCAAACAAC | GAATGTGTGTACTGCAAGCA | CTGCGACGTGAGGTATATGA |

| Efficacy Score | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.58 | 0.70 |

| G/C Content Percentage | 70% | 50% | 50% | 45% | 50% |

| Intergenic Hits | 7 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 8 |

| Intronic Hits | 11 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 11 |

| Exonic Hits | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total Off-Target Hits | 97 | 296 | 3542 | 235 | 55 |

| E6 Region 3′-gRNAs Candidates | |||||

| Selection Parameters | gRNA 1 | gRNA 2 | gRNA 3 | gRNA 4 | gRNA 5 |

| PAM Site | TTT | TTA | TTG | TTC | TTT |

| 20-nt Target Sequence | GCAACCAGAGACAACTGATC | AATGACAGCTCAGAGGAGG | TGCGTACAAAGCACACACGT | GTACTTTGGAAGACCTGTTA | GGAAGACCTGTTAATGGGCA |

| Efficacy Score | 0.60 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 0.78 | 0.65 |

| G/C Content Percentage | 50% | 50% | 50% | 40% | 50% |

| Intergenic Hits | 8 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 7 |

| Intronic Hits | 11 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 11 |

| Exonic Hits | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total Off-Target Hits | 166 | 328 | 82 | 262 | 168 |

| E6 Region 5′-gRNA Finalists | |||||

| gRNA | Bulge Type | Observed Summary (Min/Max) | Bulge Length (nt) | Mismatch Count (n) | Potential Off-Target Sites (n) |

| gRNA 1 | DNA | Minimum | 1 | 2 | 8 |

| Maximum | 2 | 4 | 1482 | ||

| RNA | Minimum | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Maximum | 2 | 4 | 16,668 | ||

| gRNA 5 | DNA | Minimum | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| Maximum | 2 | 4 | 1083 | ||

| RNA | Minimum | 1 | 2 | 10 | |

| Maximum | 2 | 4 | 13,511 | ||

| E6 Region 3′-gRNA Finalists | |||||

| gRNA | Bulge Type | Observed Summary (Min/Max) | Bulge Length (nt) | Mismatch Count (n) | Potential Off-Target Sites (n) |

| gRNA 2 | DNA | Minimum | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Maximum | 2 | 4 | 13,420 | ||

| RNA | Minimum | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Maximum | 2 | 4 | 107,820 | ||

| gRNA 3 | DNA | Minimum | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Maximum | 2 | 4 | 4360 | ||

| RNA | Minimum | 1 | 2 | 24 | |

| Maximum | 2 | 4 | 19,830 | ||

| Variant ID | gRNA | pH | Cluster # | Cluster Size | HADDOCK Score (±SD) | RMSD (±SD) | vdW Energy (kcal/mol ± SD) | BSA (Å2 ± SD) |

| Cas12j2_WT | 1 | 4 | 2 | 22 | 33.0 ± 16.6 | 16.3 ± 0.1 | −85.0 ± 8.8 | 3093.2 ± 134.4 |

| 5 | 4 | 6 | 30.1 ± 38.6 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | −102.0 ± 13.9 | 3293.0 ± 188.1 | ||

| 6 | 2 | 19 | 32.6 ± 16.2 | 16.3 ± 0.1 | −81.2 ± 3.8 | 3035.6 ± 108.0 | ||

| 7 | 2 | 17 | 43.6 ± 7.0 | 16.3 ± 0.1 | −85.2 ± 8.7 | 3039.6 ± 114.8 | ||

| 8 | 2 | 19 | 32.6 ± 16.2 | 16.3 ± 0.1 | −81.2 ± 3.8 | 3035.6 ± 108.0 | ||

| 2 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 46.3 ± 11.2 | 6.4 ± 0.3 | −79.2 ± 11.3 | 2912.0 ± 249.9 | |

| 5 | 2 | 11 | 46.5 ± 11.4 | 6.5 ± 0.3 | −80.2 ± 11.6 | 2935.2 ± 248.1 | ||

| 6 | 2 | 17 | 22.4 ± 8.2 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | −97.8 ± 16.7 | 3455.1 ± 306.4 | ||

| 7 | 2 | 11 | 26.2 ± 9.2 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | −92.9 ± 9.5 | 3223.8 ± 143.7 | ||

| 8 | 2 | 17 | 32.1 ± 11.1 | 6.2 ± 0.0 | −86.5 ± 3.4 | 3140.2 ± 131.9 | ||

| Cas12j2_F1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 11 | 108.1 ± 23.9 | 12.5 ± 0.6 | −62.2 ± 14.2 | 2199.6 ± 230.7 |

| 5 | 1 | 19 | 109.0 ± 11.1 | 13.0 ± 0.0 | −64.7 ± 8.2 | 2168.7 ± 302.3 | ||

| 6 | 3 | 6 | 99.6 ± 5.1 | 12.6 ± 0.3 | −93.5 ± 9.1 | 2773.5 ± 235.9 | ||

| 7 | 5 | 6 | 95.4 ± 35.7 | 10.9 ± 0.5 | −73.4 ± 14.4 | 2638.0 ± 369.1 | ||

| 8 | 8 | 4 | 132.4 ± 27.9 | 10.7 ± 0.2 | −60.3 ± 3.9 | 2307.6 ± 135.7 | ||

| 2 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 82.8 ± 22.2 | 14.0 ± 0.1 | −89.5 ± 10.3 | 2876.9 ± 140.8 | |

| 5 | 5 | 6 | 96.2 ± 13.0 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | −96.5 ± 4.5 | 3260.3 ± 263.8 | ||

| 6 | 5 | 8 | 91.8 ± 14.8 | 8.6 ± 0.4 | −80.4 ± 11.9 | 2647.2 ± 313.9 | ||

| 7 | 5 | 6 | 103.8 ± 29.8 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | −70.2 ± 18.6 | 2614.7 ± 314.2 | ||

| 8 | 3 | 7 | 103.6 ± 20.3 | 12.8 ± 0.1 | −85.7 ± 8.8 | 2680.9 ± 204.7 | ||

| Cas12j2_F2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 12 | 40.7 ± 11.5 | 17.1 ± 0.3 | −94.5 ± 3.2 | 3079.6 ± 262.1 |

| 5 | 1 | 15 | 109.4 ± 12.4 | 11.5 ± 0.4 | −83.3 ± 6.8 | 2632.5 ± 258.8 | ||

| 6 | 2 | 7 | 51.4 ± 5.0 | 13.6 ± 0.2 | −90.7 ± 2.6 | 2890.7 ± 102.7 | ||

| 7 | 3 | 5 | 70.7 ± 19.7 | 12.9 ± 0.7 | −80.4 ± 18.4 | 2854.2 ± 243.1 | ||

| 8 | 3 | 8 | 66.6 ± 15.3 | 16.1 ± 0.1 | −86.1 ± 5.9 | 2935.4 ± 235.7 | ||

| 2 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 79.5 ± 21.0 | 12.6 ± 0.1 | −77.2 ± 9.8 | 2695.8 ± 279.6 | |

| 5 | 3 | 5 | 48.8 ± 8.8 | 11.8 ± 0.2 | −92.0 ± 4.8 | 3005.0 ± 78.4 | ||

| 6 | 6 | 4 | 52.5 ± 32.1 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | −88.4 ± 10.1 | 3184.8 ± 180.9 | ||

| 7 | 4 | 5 | 74.5 ± 39.0 | 12.4 ± 0.2 | −67.0 ± 12.5 | 2618.4 ± 233.5 | ||

| 8 | 4 | 5 | 64.6 ± 16.1 | 13.5 ± 0.1 | −82.0 ± 9.0 | 2744.4 ± 73.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Boren, C.; Kumar, R.; Gollahon, L. In Silico Design and Characterization of a Rationally Engineered Cas12j2 Gene Editing System for the Treatment of HPV-Associated Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021054

Boren C, Kumar R, Gollahon L. In Silico Design and Characterization of a Rationally Engineered Cas12j2 Gene Editing System for the Treatment of HPV-Associated Cancers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021054

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoren, Caleb, Rahul Kumar, and Lauren Gollahon. 2026. "In Silico Design and Characterization of a Rationally Engineered Cas12j2 Gene Editing System for the Treatment of HPV-Associated Cancers" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021054

APA StyleBoren, C., Kumar, R., & Gollahon, L. (2026). In Silico Design and Characterization of a Rationally Engineered Cas12j2 Gene Editing System for the Treatment of HPV-Associated Cancers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021054