Serum Proteomic Profiling Identifies ACSL4 and S100A2 as Novel Biomarkers in Feline Calicivirus Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

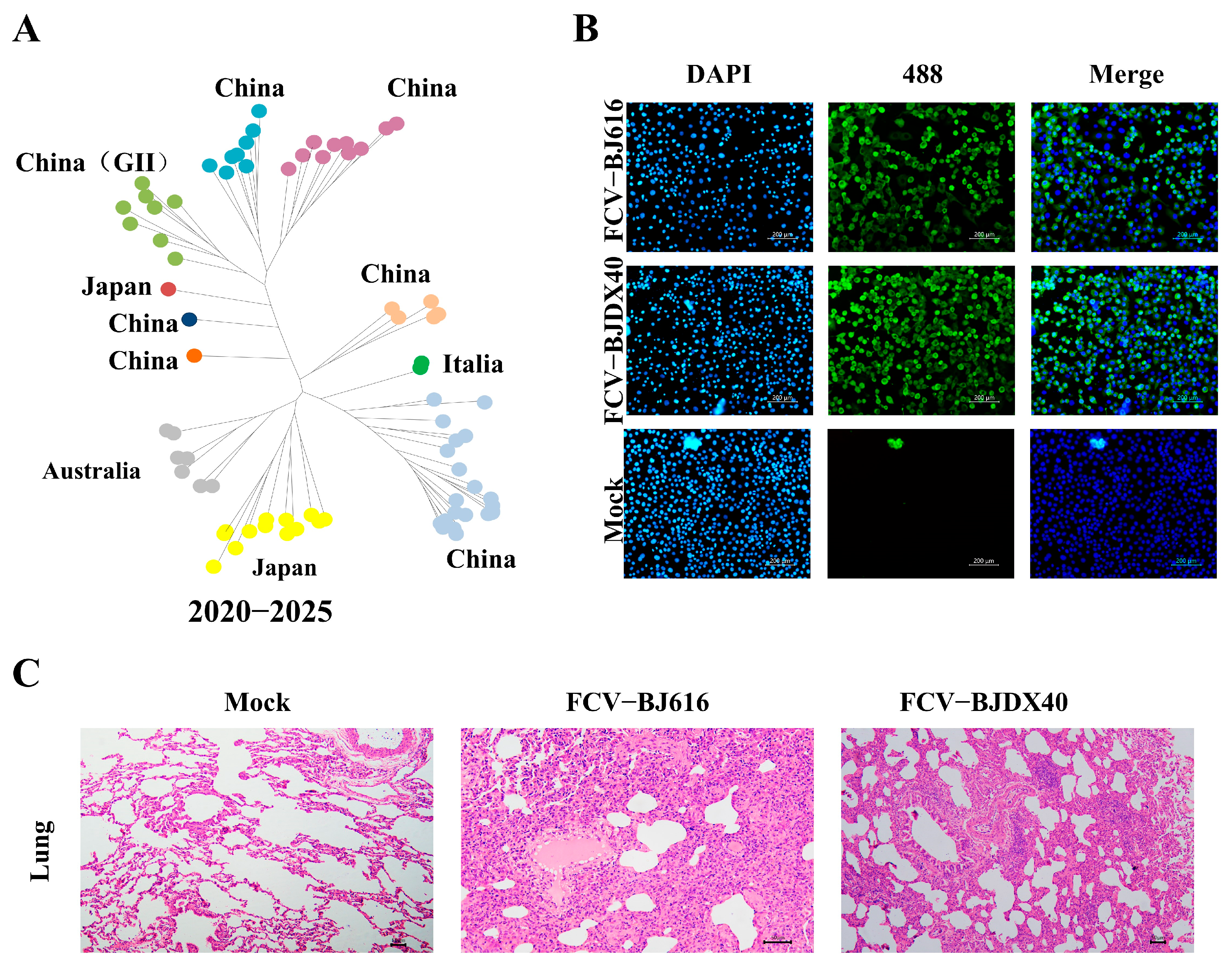

2.1. FCV Infection Causes Severe Lung Damage in Cats

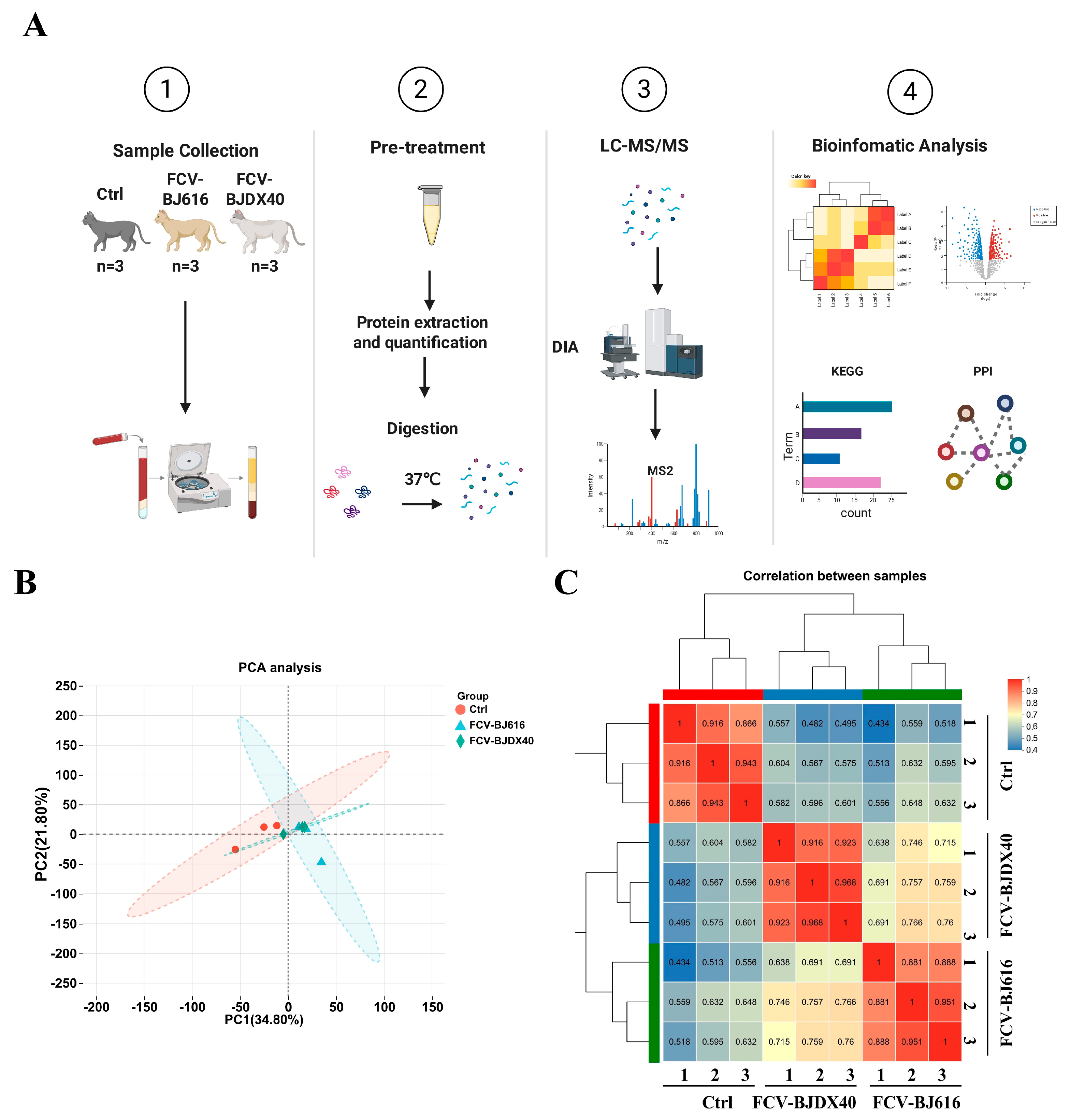

2.2. DIA Sample Quality Control

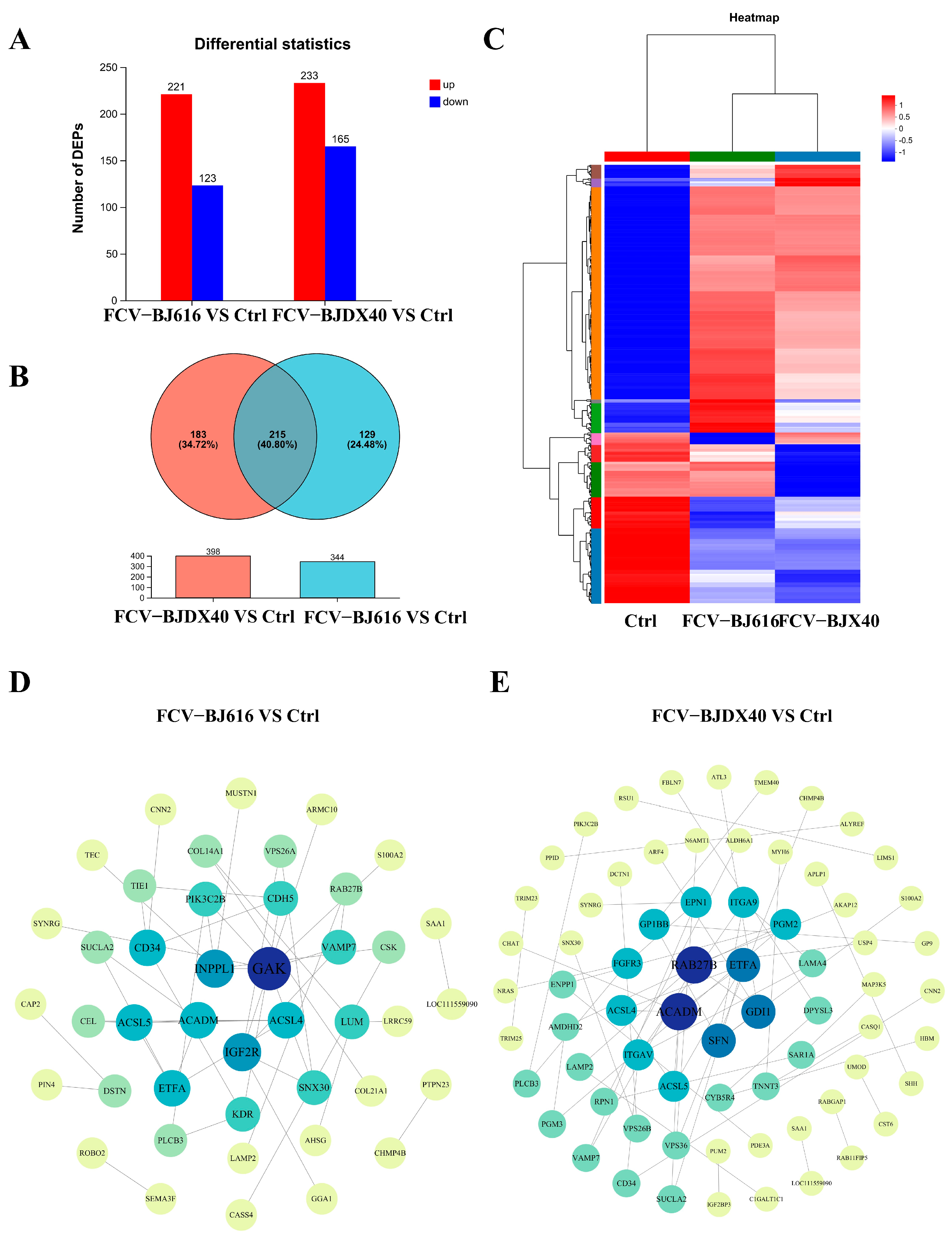

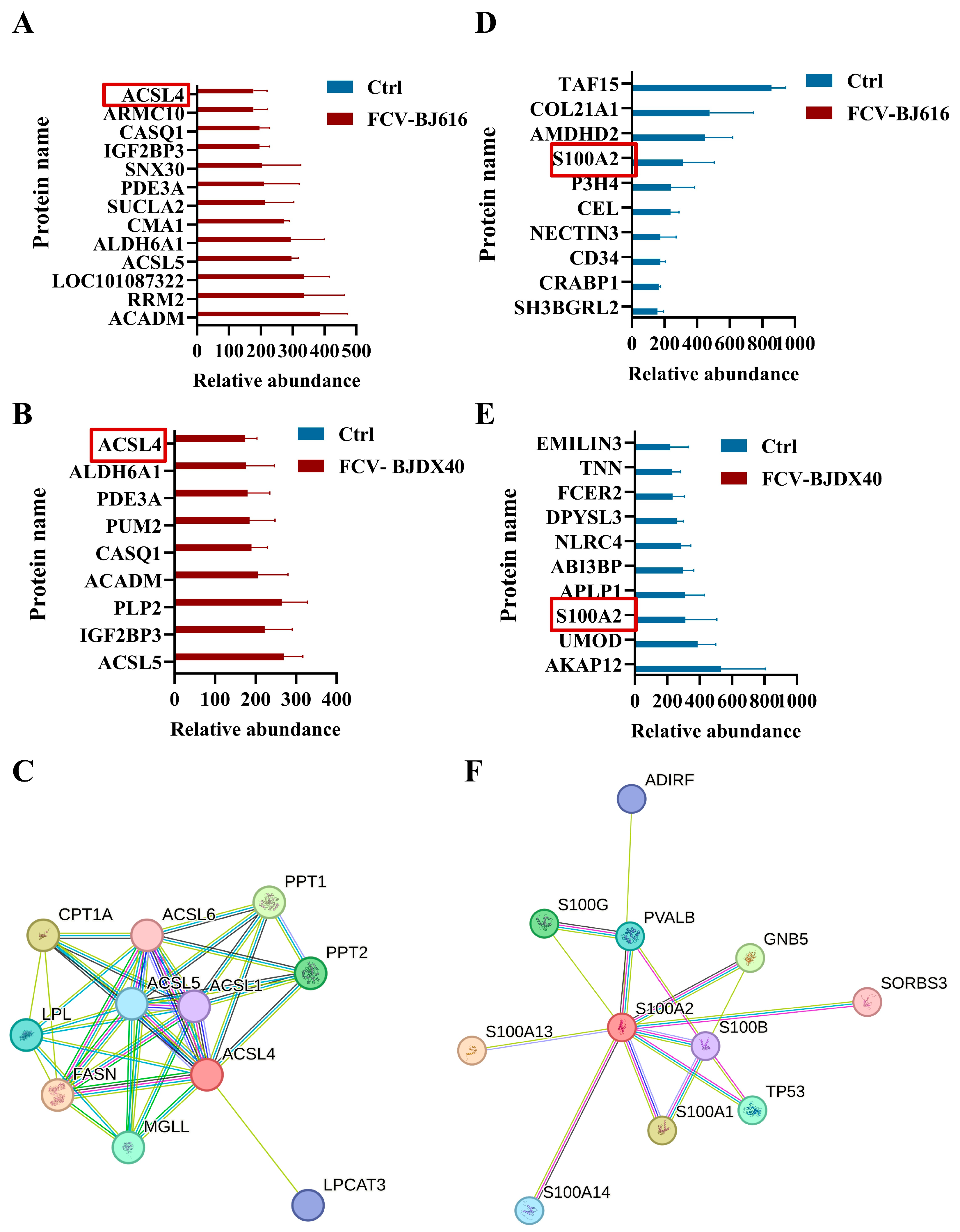

2.3. Differential Protein Expression and Interaction Analysis of Cat Sera Infected with FCV-BJ616 and FCV-BJDX40

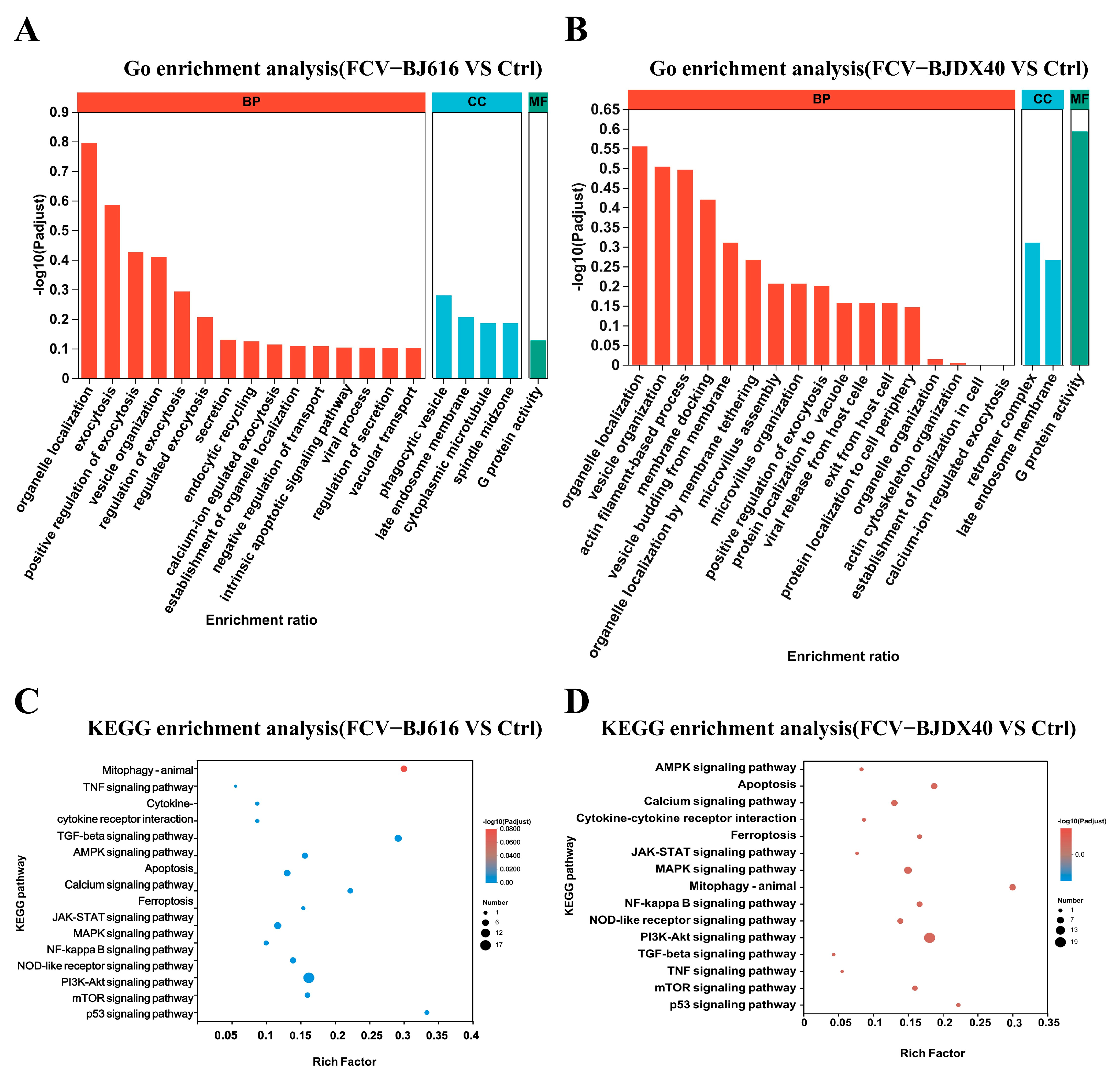

2.4. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analyses for DPEs

2.5. Analysis of Candidate Biomarkers in DEPs

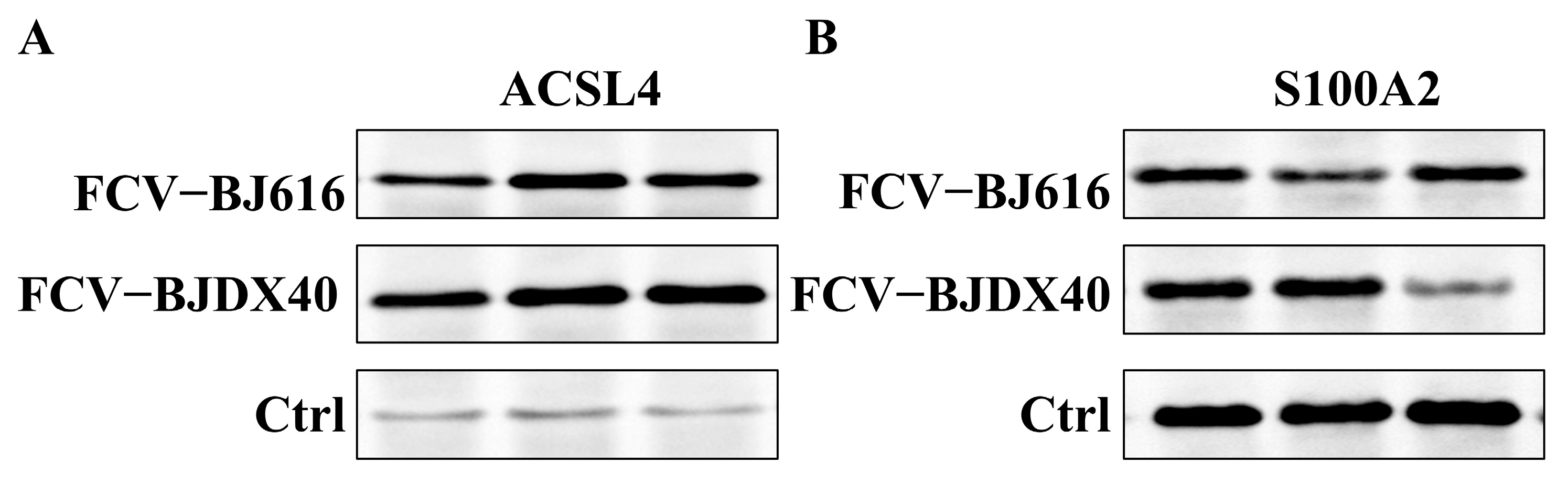

2.6. The Candidate Protein Was Validated by Western Blotting

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cells and Viruses

4.2. Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA)

4.3. Animal Experimentation

4.4. Serum Protein Extraction and Trypsin Digestion

4.5. DIA Mass Detection

4.6. Bioinformatics Analysis

4.7. Western Blotting

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Gou, H.; Bao, S. Update on feline calicivirus: Viral evolution, pathogenesis, epidemiology, prevention and control. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1388420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hosie, M.J.; Hartmann, K.; Egberink, H.; Truyen, U.; Tasker, S.; Belák, S.; Boucraut-Baralon, C.; Frymus, T.; Lloret, A.; et al. Calicivirus Infection in Cats. Viruses 2022, 14, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.; Li, D.; Xie, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, X.; Teng, Y.; Zhao, S.; et al. Nitazoxanide protects cats from feline calicivirus infection and acts synergistically with mizoribine in vitro. Antivir. Res. 2020, 182, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanave, G.; Buonavoglia, A.; Pellegrini, F.; Di Martino, B.; Di Profio, F.; Diakoudi, G.; Catella, C.; Omar, A.H.; Vasinioti, V.I.; Cardone, R.; et al. An Outbreak of Limping Syndrome Associated with Feline Calicivirus. Animals 2023, 13, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, B.; Lanave, G.; Di Profio, F.; Melegari, I.; Marsilio, F.; Camero, M.; Catella, C.; Capozza, P.; Bányai, K.; Barrs, V.R.; et al. Identification of feline calicivirus in cats with enteritis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 2579–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, A.; Verin, R.; Buldrini, I.; Zamagni, S.; Morini, M.; Terrusi, A.; Gallina, L.; Urbani, L.; Dondi, F.; Battilani, M. Natural cases of polyarthritis associated with feline calicivirus infection in cats. Vet. Res. Commun. 2022, 46, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, M.; Ballin, A.; Schulz, B.; Dörfelt, R.; Hartmann, K. Treatment of acute viral feline upper respiratory tract infections. Tierarztliche Praxis Ausgabe K Kleintiere/Heimtiere 2019, 47, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caringella, F.; Elia, G.; Decaro, N.; Martella, V.; Lanave, G.; Varello, K.; Catella, C.; Diakoudi, G.; Carelli, G.; Colaianni, M.L.; et al. Feline calicivirus infection in cats with virulent systemic disease, Italy. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 124, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, D.; Hong, Y.J.; Hwang, C.Y.; Hyun, J.E. Outbreaks of nosocomial feline calicivirus-associated virulent systemic disease in Korea. J. Vet. Sci. 2024, 25, e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, A.C.; Vieira, M.C.; Oliveira, M.; Lourenço, L.; Viegas, C.; Faísca, P.; Seixas, F.; Requicha, J.F.; Pires, M.A. Feline calicivirus and natural killer cells: A study of its relationship in chronic gingivostomatitis. Vet. World 2023, 16, 1708–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaviero, M.; de Almeida, B.A.; de Castro, L.T.; Panziera, W.; Pavarini, S.P.; Driemeier, D.; Sonne, L. Feline herpesvirus and calicivirus: Occurrence and pathology in cats with respiratory disease. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2025, 69, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, W.D.; Xie, Q.Q.; Wang, J.G.; Gu, C.C.; Ji, Z.H.; Xiao, J.; Liu, W.Q. Induction of COX-2 by feline calicivirus via activation of the MEK1-ERK1/2 pathway, and attenuation of feline lung inflammation and injury by MEK1 inhibitor AZD6244 (selumetinib). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 604, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Shi, M.; Cai, S.; Su, Y.; Chen, R.; Huang, C.; Chen, D.D.Y. Data-Driven Tool for Cross-Run Ion Selection and Peak-Picking in Quantitative Proteomics with Data-Independent Acquisition LC-MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 16558–16566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, R.; Barth, T.K.; Imhof, A.; Thalmeier, F.; Lange-Sperandio, B. Comparison of clean catch and bag urine using LC-MS/MS proteomics in infants. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2024, 39, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, C.; Schrama, E.J.; Kotol, D.; Hober, A.; Koeks, Z.; van de Velde, N.M.; Verschuuren, J.; Niks, E.H.; Edfors, F.; Spitali, P.; et al. Contrasting Becker and Duchenne muscular dystrophy serum biomarker candidates by using data independent acquisition LC-MS/MS. Skelet. Muscle 2025, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Xu, F.; Sun, J.; Song, J.; Shen, Y.; Lu, S.; Ding, H.; Lan, L.; Chen, C.; Ma, W.; et al. Integrative multi-omics analysis unravels the host response landscape and reveals a serum protein panel for early prognosis prediction for ARDS. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Tang, X.; Zhou, N.; Wang, X.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhi, Y. Study of Urinary Protein Biomarkers in Hereditary Angioedema. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2025, 35, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, Y.; Nakai, Y.; Shin, J.; Hara, M.; Takeda, Y.; Kubo, S.; Jeremiah, S.S.; Ino, Y.; Akiyama, T.; Moriyama, K.; et al. Identification of serum prognostic biomarkers of severe COVID-19 using a quantitative proteomic approach. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, D.; Deng, M. Comparative Analysis of Serum Proteins Between Hepatitis B Virus Genotypes B and C Infection by DIA-Based Quantitative Proteomics. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 4701–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Liu, X.; Song, R.; Tao, W.; Yu, Y.; Yang, H.; Shan, H.; Zhang, C. Genetic and pathogenicity analysis for the two FCV strains isolated from Eastern China. Vet. Res. Commun. 2023, 47, 2127–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, L.; Hu, X.; Jiang, Y. Isolation and molecular characteristics of a recombinant feline calicivirus from Qingdao, China. Vet. Res. Forum Int. Q. J. 2023, 14, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zang, M.; Zhou, Z. Genetic and phylogenetic analysis of capsid gene of feline calicivirus in Nanjing, China. Infect. Genet. Evol. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evol. Genet. Infect. Dis. 2022, 103, 105323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamsingnok, P.; Rapichai, W.; Rattanasrisomporn, A.; Rungsuriyawiboon, O.; Choowongkomon, K.; Rattanasrisomporn, J. Comparison of PCR, Nested PCR, and RT-LAMP for Rapid Detection of Feline Calicivirus Infection in Clinical Samples. Animals 2024, 14, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, Y.H.; Park, K.T. Development of a novel reverse transcription PCR and its application to field sample testing for feline calicivirus prevalence in healthy stray cats in Korea. J. Vet. Sci. 2020, 21, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolim, V.M.; Pavarini, S.P.; Campos, F.S.; Pignone, V.; Faraco, C.; Muccillo, M.S.; Roehe, P.M.; da Costa, F.V.; Driemeier, D. Clinical, pathological, immunohistochemical and molecular characterization of feline chronic gingivostomatitis. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2017, 19, 403–409, Correction in J. Feline Med. Surg. 2017, 19, NP1. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098612X16639004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliocca, M.; Mandrioli, L.; Battilani, M.; Bacci, B.; Ballotta, G.; Anjomanibenisi, M.; Urbani, L.; Martella, L.; Facile, V.; Scarpellini, R.; et al. Description of a Virulent Systemic Feline Calicivirus Infection in a Kitten with Footpads Oedema and Fatal Pneumonia. Pathogens 2025, 14, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and contributor of ferroptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 478, 1338–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Q.Z.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Yan, H.F.; Zou, T.; Shu, Y.; Ding, X.L.; Zou, J.J.; Xu, S.; Tang, F.; et al. Thrombin induces ACSL4-dependent ferroptosis during cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, P.; Wang, W.; Wang, W.; Kryczek, I.; Li, X.; Bian, Y.; Sell, A.; Wei, S.; Grove, S.; Johnson, J.K.; et al. CD8(+) T cells and fatty acids orchestrate tumor ferroptosis and immunity via ACSL4. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 365–378.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Hu, B.X.; Li, Z.L.; Du, T.; Shan, J.L.; Ye, Z.P.; Peng, X.D.; Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.Y.; et al. PKCβII phosphorylates ACSL4 to amplify lipid peroxidation to induce ferroptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Spencer, C.B.; Ortoga, L.; Zhang, H.; Miao, C. Histone lactylation-regulated METTL3 promotes ferroptosis via m6A-modification on ACSL4 in sepsis-associated lung injury. Redox Biol. 2024, 74, 103194, Correction in Redox Biol. 2025, 82, 103616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2025.103616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, J.; Liang, D.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z. Knockdown of SHP2 attenuated LPS-induced ferroptosis via downregulating ACSL4 expression in acute lung injury. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2023, 51, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, R.; Zhao, H.; Xiong, Y.; He, P. CircEXOC5 promotes ferroptosis by enhancing ACSL4 mRNA stability via binding to PTBP1 in sepsis-induced acute lung injury. Immunobiology 2022, 227, 152219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.C.; Li, C.Y.; Kuo, C.Y.; Kuo, Y.Z.; Fang, W.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Hsieh, T.C.; Kao, H.Y.; Kuo, Y.; Kang, Y.R.; et al. The p53-S100A2 Positive Feedback Loop Negatively Regulates Epithelialization in Cutaneous Wound Healing. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.M.; Cho, J.Y. S100A2 level changes are related to human periodontitis. Mol. Cells 2011, 32, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.T.; Jin, Y.T.; Tsai, W.C.; Wang, S.T.; Lin, Y.C.; Chang, M.T.; Wu, L.W. S100A2, a potential marker for early recurrence in early-stage oral cancer. Oral. Oncol. 2005, 41, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, J.O.; McArdle, F.; Dawson, S.; Carter, S.D.; Gaskell, C.J.; Gaskell, R.M. Studies on the role of feline calicivirus in chronic stomatitis in cats. Vet. Microbiol. 1991, 27, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulet, H.; Brunet, S.; Soulier, M.; Leroy, V.; Goutebroze, S.; Chappuis, G. Comparison between acute oral/respiratory and chronic stomatitis/gingivitis isolates of feline calicivirus: Pathogenicity, antigenic profile and cross-neutralisation studies. Arch. Virol. 2000, 145, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, S.; Meng, C.; Li, C.; Liu, G. The recombinant feline herpesvirus 1 expressing feline Calicivirus VP1 protein is safe and effective in cats. Vaccine 2024, 42, 126468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, H.I.; Grinfeld, D.; Giannakopulos, A.; Petzoldt, J.; Shanley, T.; Garland, M.; Denisov, E.; Peterson, A.C.; Damoc, E.; Zeller, M.; et al. Parallelized Acquisition of Orbitrap and Astral Analyzers Enables High-Throughput Quantitative Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 15656–15664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Pezacki, A.T.; Matier, C.D.; Wang, W.X. A novel route of intercellular copper transport and detoxification in oyster hemocytes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, R.; Shui, W. Acquisition and Analysis of DIA-Based Proteomic Data: A Comprehensive Survey in 2023. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP 2024, 23, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.; Shi, C.; Liu, L.; Han, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Fu, W.; Gao, H.; Huang, H.; et al. Majorbio Cloud 2024: Update single-cell and multiomics workflows. iMeta 2024, 3, e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bandla, C.; Kundu, D.J.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Bai, J.; Hewapathirana, S.; John, N.S.; Prakash, A.; Walzer, M.; Wang, S.; et al. The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D543–D553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, C.; Liu, H.; Gu, H.; Wu, D.; Tang, X.; Liang, L.; Hou, S.; Ding, J.; Liang, R. Serum Proteomic Profiling Identifies ACSL4 and S100A2 as Novel Biomarkers in Feline Calicivirus Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021047

Xu C, Liu H, Gu H, Wu D, Tang X, Liang L, Hou S, Ding J, Liang R. Serum Proteomic Profiling Identifies ACSL4 and S100A2 as Novel Biomarkers in Feline Calicivirus Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021047

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Chunmei, Hao Liu, Haotian Gu, Di Wu, Xinming Tang, Lin Liang, Shaohua Hou, Jiabo Ding, and Ruiying Liang. 2026. "Serum Proteomic Profiling Identifies ACSL4 and S100A2 as Novel Biomarkers in Feline Calicivirus Infection" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021047

APA StyleXu, C., Liu, H., Gu, H., Wu, D., Tang, X., Liang, L., Hou, S., Ding, J., & Liang, R. (2026). Serum Proteomic Profiling Identifies ACSL4 and S100A2 as Novel Biomarkers in Feline Calicivirus Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021047