Effects of N3SA Analogues on Cerebral and Peripheral Arteriolar Vasomotion in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

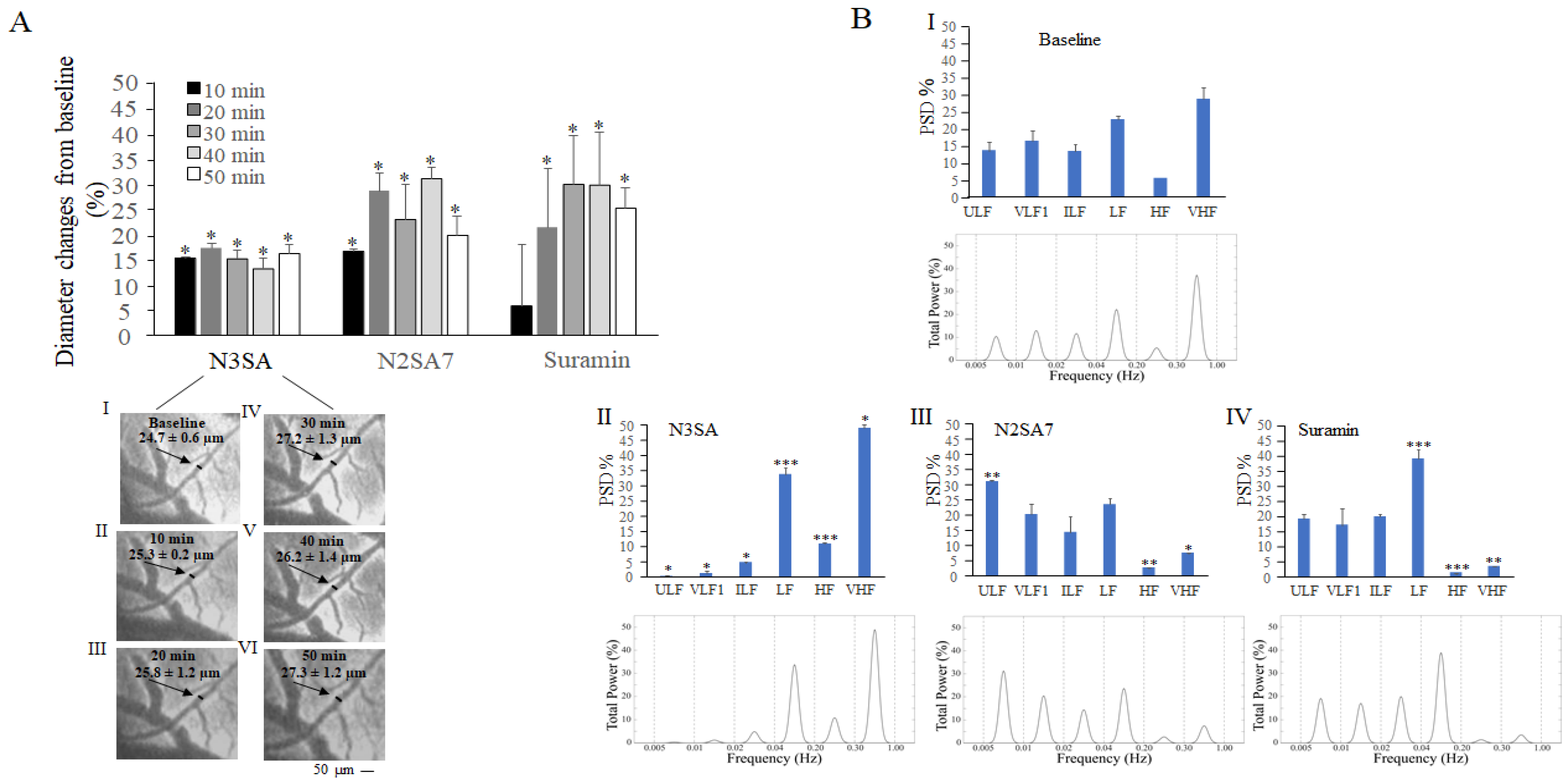

2.1. Effects of N3SA Analogues on Vascular Tone in Cerebral Microcirculation

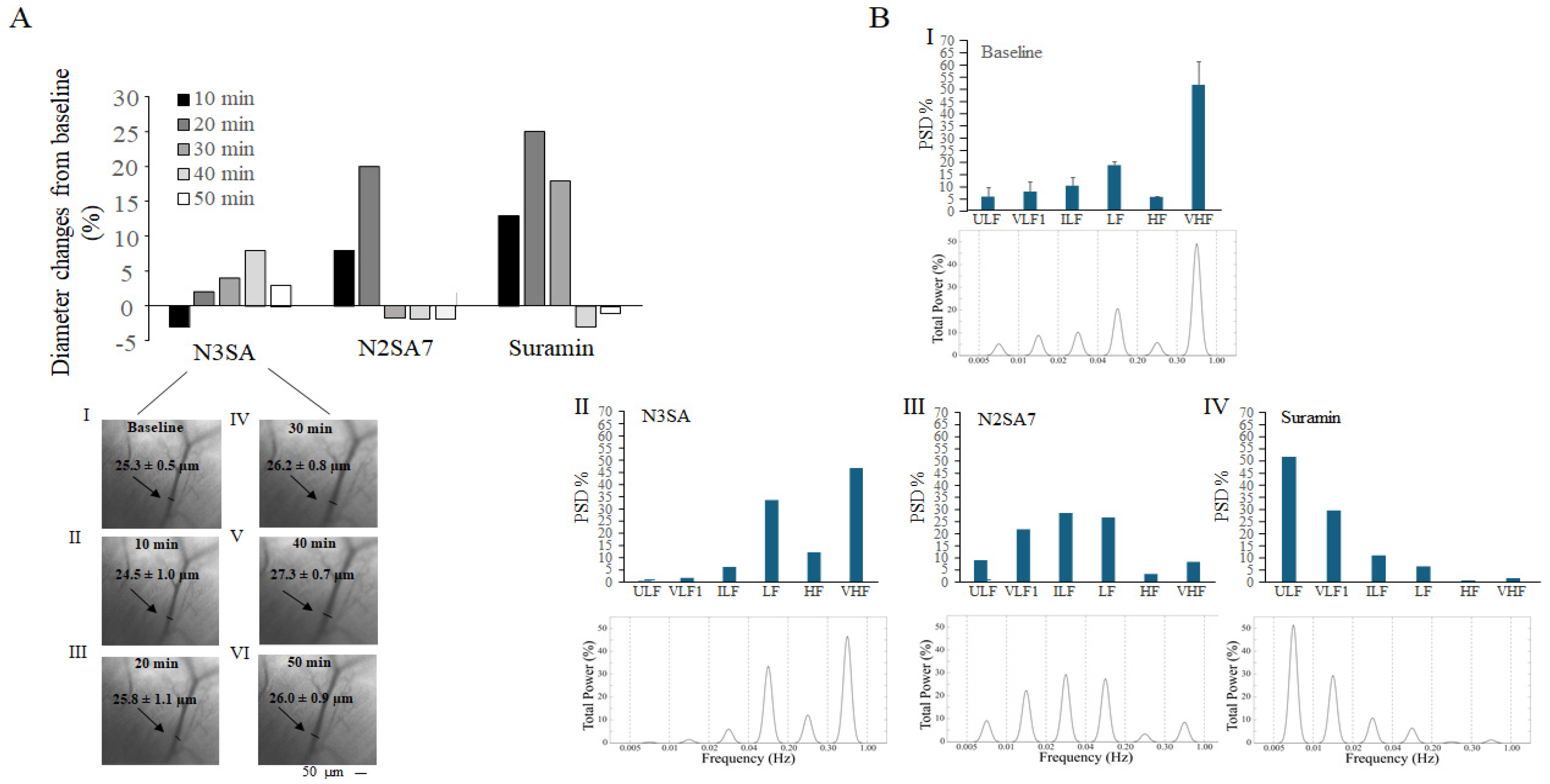

2.2. Effects of N3SA Analogues on Vascular Tone in Femoral Muscle Microcirculation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Groups

4.2. Operative Procedure to Assess the Arteriolar Diameter Changes

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Engberink, O.; Wijnanda, J.F.; van den Bogaard, B.; Brewster, L.M.; van den Born, B.J.H. Effects of thiazide-type and thiazide-like diuretics on cardiovascular events and mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension 2015, 65, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafidis, P.A.; Nilsson, P.M. The effects of thiazolidinediones on blood pressure levels—A systematic review. Blood Press. 2006, 15, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, T.D.; Sander, G.E. Effects of thiazolidinediones on blood pressure. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2007, 9, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.H.; Johnson, J.A. Mechanisms and pharmacogenetic signals underlying thiazide diuretics blood pressure response. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016, 27, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson-Welsh, L.; Dejana, E.; McDonald, D.M. Permeability of the Endothelial Barrier: Identifying and Reconciling Controversies. Trends Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, D. The thiazide target, at last. Science 2025. Available online: https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/thiazide-target-last (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Horita, S.; Nakamura, M.; Satoh, N.; Suzuki, M.; Seki, G. Thiazolidinediones and Edema: Recent Advances in the Pathogenesis of Thiazolidinediones-Induced Renal Sodium Retention. PPAR Res. 2015, 2015, 646423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, R.M.; Soleimani, M. Mechanism of Thiazide Diuretic Arterial Pressure Reduction: The Search Continues. Front Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Murmu, A.; Matore, B.W.; Roy, P.P.; Singh, J. Thiazolidinedione an auspicious scaffold as PPAR-γ agonist: Its possible mechanism to Manoeuvre against insulin resistant diabetes mellitus. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2024, 11, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, M.E.; Fravel, M.A. Thiazide and the Thiazide-Like Diuretics: Review of Hydrochlorothiazide, Chlorthalidone, and Indapamide. Am. J. Hypertens. 2022, 35, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

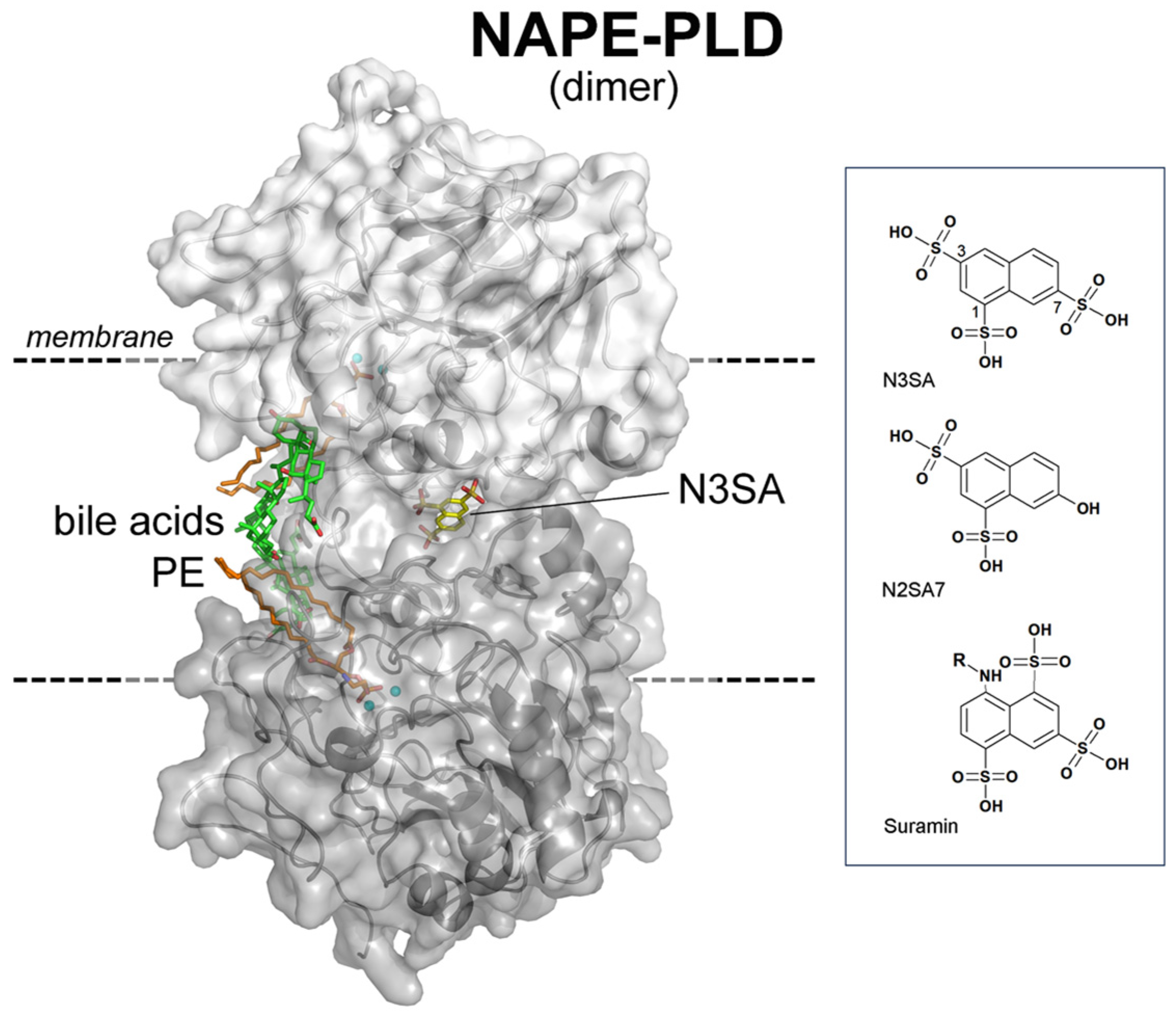

- Chiarugi, S.; Margheriti, F.; De Lorenzi, V.; Martino, E.; Margheritis, E.G.; Moscardini, A.; Marotta, R.; Chavez-Sanjugiuan, A.; Del Seppia, C.; Federighi, G.; et al. NAPE-PLD is target of thiazide diuretics. Cell Chem. Biol. 2025, 32, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, G. State of the Art Review: Thiazide Diuretics Exploit the Endocannabinoid System via NAPE-PLD. Am. J. Hypertens. 2025, hpaf174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomba, N.; Patel, S. Circuit mechanisms governing endocannabinoid modulation of affective behaviour and stress adaptation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2025, 26, 677–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, L.; Everard, A.; Van Hul, M.; Essaghir, A.; Duparc, T.; Matamoros, S.; Plovier, H.; Castel, J.; Denis, R.G.; Bergiers, M.; et al. Adipose tissue NAPE-PLD controls fat mass development by altering the browning process and gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minor, K.M.; Letko, A.; Becker, D.; Drögemüller, M.; Mandigers, P.J.J.; Bellekom, S.R.; Leegwater, P.A.J.; Stassen, Q.E.M.; Putschbach, K.; Fischer, A.; et al. Canine NAPEPLD-associated models of human myelin disorders. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steverding, D.; Troeberg, L. 100 years since the publication of the suramin formula. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanovska, A.; Bracic, M.; Kvernmo, H.D. Wavelet analysis of oscillations in the peripheral blood circulation measured by laser Doppler technique. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1999, 46, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapi, D.; Mastantuono, T.; Di Maro, M.; Varanini, M.; Colantuoni, A. Low-Frequency Components in Rat Pial Arteriolar Rhythmic Diameter Changes. J. Vasc. Res. 2017, 54, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backmann, S.B.; Rudolphi, C.F.; Imenez Silva, P.H.; Fenton, R.A.; Hoorn, E.J. Thiazide-induced hyponatremia. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, L.H.; Hurd, Y.L. Endocannabinoid signalling in reward and addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, C.; Morales, P.; Reggio, P.H. Cannabinoid ligands targeting TRP channels. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Marzo, V. New approaches and challenges to targeting the endocannabinoid system. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 623–639, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzęda, E.; Schlicker, E.; Toczek, M.; Zalewska, I.; Baranowska-Kuczko, M.; Malinowska, B. CB1 receptor activation in the rat paraventricular nucleus induces bi-directional cardiovascular effects via modification of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2017, 390, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, H.; Toyang, N.; Steele, B.; Bryant, J.; Ngwa, W. The Endocannabinoid System: A Potential Target for the Treatment of Various Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ursino, M.; Colantuoni, A.; Bertuglia, S. Vasomotion and blood flow regulation in hamster skeletal muscle microcirculation: A theoretical and experimental study. Microvasc. Res. 1998, 56, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuglia, S.; Colantuoni, A.; Coppini, G.; Intaglietta, M. Hypoxia- or hyperoxia-induced changes in arteriolar vasomotion in skeletal muscle microcirculation. Am. J. Physiol. 1991, 260, H362–H372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantuoni, A.; Bertuglia, S.; Intaglietta, M. Quantitation of rhythmic diameter changes in arterial microcirculation. Am. J. Physiol. 1984, 246, H508–H517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapi, D.; Di Maro, M.; Mastantuono, T.; Starita, N.; Ursino, M.; Colantuoni, A. Arterial Network Geometric Characteristics and Regulation of Capillary Blood Flow in Hamster Skeletal Muscle Microcirculation. Front. Physiol. 2019, 9, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassab, G.S.; Imoto, K.; White, F.C.; Rider, C.A.; Fung, Y.C.B.; Bloor, C.M. Coronary arterial tree remodelling in right ventricular hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. 1993, 265, H366–H375. [Google Scholar]

- Lapi, D.; Varanini, M.; Galasso, L.; Di Maro, M.; Federighi, G.; Del Seppia, C.; Colantuoni, A.; Scuri, R. Effects of Mandibular Extension on Pial Arteriolar Diameter Changes in Glucocorticoid-Induced Hypertensive Rats. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapi, D.; Di Maro, M.; Serao, N.; Chiurazzi, M.; Varanini, M.; Sabatino, L.; Scuri, R.; Colantuoni, A.; Guida, B. Geometric Features of the Pial Arteriolar Networks in Spontaneous Hypertensive Rats: A Crucial Aspect Underlying the Blood Flow Regulation. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 664683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varanini, M.; De Paolis, G.; Emdin, M.; MacErata, A.; Pola, A. A multiresolution transform for the analysis of cardiovascular time series. Comput. Cardiol. 1998, 25, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lapi, D.; Federighi, G.; Tramonti Fantozzi, M.P.; Garau, G.; Scuri, R. Effects of N3SA Analogues on Cerebral and Peripheral Arteriolar Vasomotion in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021006

Lapi D, Federighi G, Tramonti Fantozzi MP, Garau G, Scuri R. Effects of N3SA Analogues on Cerebral and Peripheral Arteriolar Vasomotion in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(2):1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021006

Chicago/Turabian StyleLapi, Dominga, Giuseppe Federighi, Maria Paola Tramonti Fantozzi, Gianpiero Garau, and Rossana Scuri. 2026. "Effects of N3SA Analogues on Cerebral and Peripheral Arteriolar Vasomotion in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 2: 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021006

APA StyleLapi, D., Federighi, G., Tramonti Fantozzi, M. P., Garau, G., & Scuri, R. (2026). Effects of N3SA Analogues on Cerebral and Peripheral Arteriolar Vasomotion in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(2), 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27021006