Resistance to SMO Inhibitors in Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Highlighting the Role of Molecular Tumor Profiling

Abstract

1. Introduction

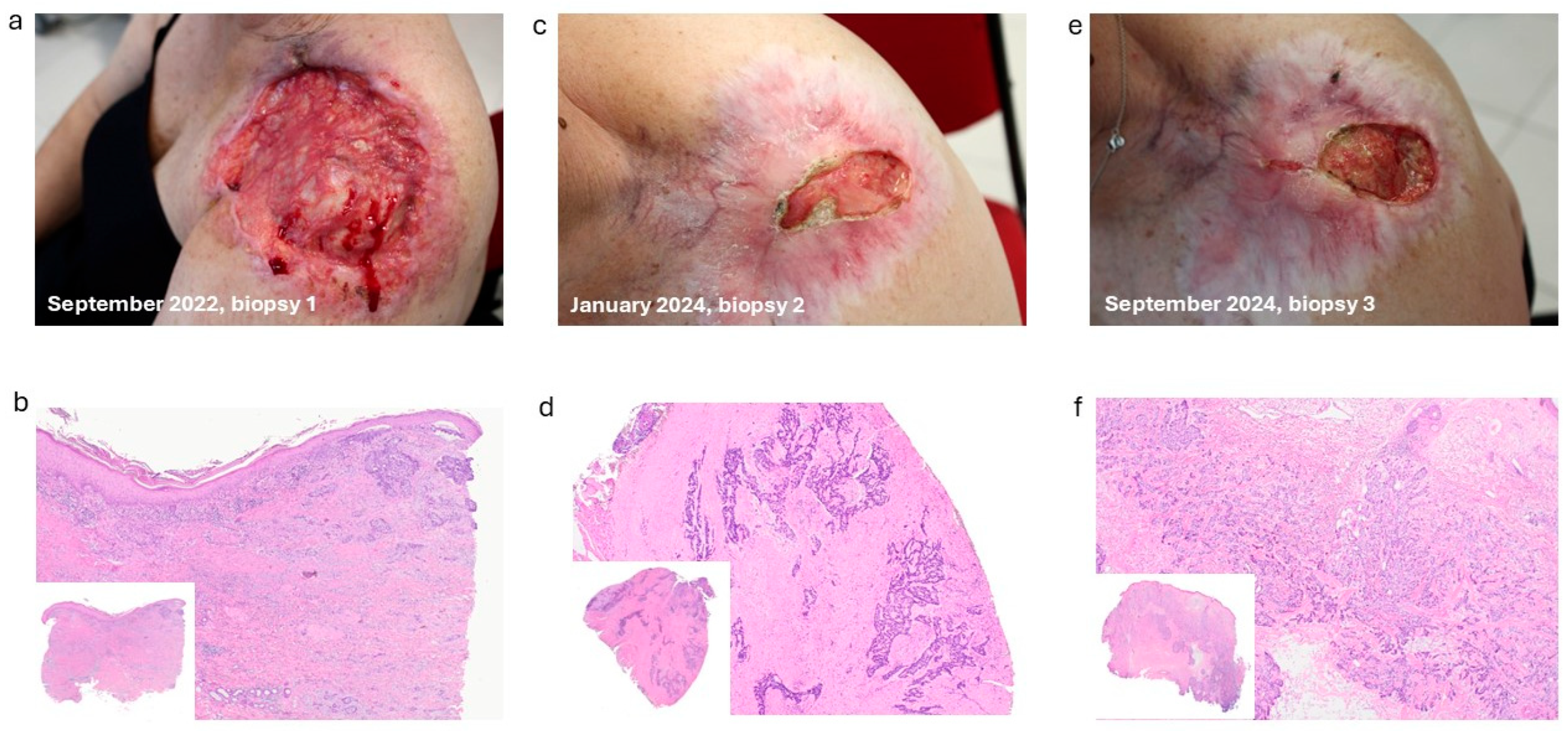

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rubin, A.I.; Chen, E.H.; Ratner, D. Basal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2262–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verkouteren, J.A.C.; Ramdas, K.H.R.; Wakkee, M.; Nijsten, T. Epidemiology of Basal Cell Carcinoma: Scholarly Review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, S.; Berrocal, A. Management of High-Risk and Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2015, 17, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, A.; Chaudhary, S.C.; Rana, M.; Elmets, C.A.; Athar, M. Basal Cell Carcinoma Pathogenesis and Therapy Involving Hedgehog Signaling and Beyond. Mol. Carcinog. 2017, 56, 2543–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farage, M.A.; Miller, K.W.; Berardesca, E.; Maibach, H.I. Clinical Implications of Aging Skin: Cutaneous Disorders in the Elderly. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2009, 10, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markota Cagalj, A.; Glibo, M.; Karin-Kujundzic, V.; Serman, A.; Vranic, S.; Serman, L.; Skara Abramovic, L.; Bukvic Mokos, Z. Hedgehog Signalling Pathway Inhibitors in the Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma: An Updated Review. J. Drug Target. 2025, 33, 1322–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, H.J.; Pau, G.; Dijkgraaf, G.J.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Modrusan, Z.; Januario, T.; Vsui, V.; Durham, A.B.; Dlugosz, A.A.; Haverty, P.M.; et al. Genomic analysis of smoothened inhibitor resistance in basal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Untaaveesup, S.; Srichana, P.; Techataweewan, G.; Pongphaew, C.; Dendumrongsup, W.; Ponvilawan, B.; Nampipat, N.; Limwongse, C. Prevalence of Genetic Alterations in Basal Cell Carcinoma Patients Resistant to Hedgehog Pathway Inhibitors: A Systematic Review. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2516701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwood, S.X.; Sarin, K.Y.; Whitson, R.J.; Li, J.R.; Kim, G.; Rezaee, M.; Ally, M.S.; Kim, J.; Yao, C.; Chang, A.L.S.; et al. Smoothened n Variants Explain the Majority of Drug Resistance in Basal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Shytikov, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Chen, R.; He, Y.; Yang, Y.; Guo, W. Canonical and noncanonical NOTCH signaling in the nongenetic resistance of cancer: Distinct and concerted control. Front. Med. 2025, 19, 23–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gounder, M.M.; Rosenbaum, E.; Wu, N.; Dickson, M.A.; Sheikh, T.N.; D’Angelo, S.P.; Chi, P.; Keohan, M.L.; Erinjeri, J.P.; Antonescu, C.R.; et al. A Phase Ib/II Randomized Study of RO4929097, a Gamma-Secretase or Notch Inhibitor with or without Vismodegib, a Hedgehog Inhibitor, in Advanced Sarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.C.; Chugh, R.; Patnaik, A.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Wang, M.; Kapoun, A.M.; Xu, L.; Dupont, J.; Stagg, R.J.; Tolcher, A. A Phase 1 Dose Escalation and Expansion Study of Tarextumab (OMP-59R5) in Patients with Solid Tumors. Investig. New Drugs 2019, 37, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla, X.; Parmentier, L.; King, B.; Bezrukov, F.; Kaya, G.; Zoete, V.; Seplyarskiy, V.B.; Sharpe, H.J.; McKee, T.; Letourneau, A.; et al. Genomic Analysis Identifies New Drivers and Progression Pathways in Skin Basal Cell Carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nardo, L.; Pellegrini, C.; Di Stefani, A.; Ricci, F.; Fossati, B.; Del Regno, L.; Carbone, C.; Piro, G.; Corbo, V.; Delfino, P.; et al. Molecular Alterations in Basal Cell Carcinoma Subtypes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossi, P.; Ascierto, P.A.; Basset-Seguin, N.; Dreno, B.; Dummer, R.; Hauschild, A.; Mohr, P.; Kaufmann, R.; Pellacani, G.; Puig, S.; et al. Long-term strategies for management of advanced basal cell carcinoma with hedgehog inhibitors. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2023, 189, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssen, F.; Garcia, M.U.; Folkersen, L.; Pedersen, A.S.; Lescai, F.; Jodoin, S.; Miller, E.; Seybold, M.; Wacker, O.; Smith, N.; et al. Scalable and Efficient DNA Sequencing Analysis on Different Compute Infrastructures Aiding Variant Discovery. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2024, 6, lqae031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Locus | Type | Genes | Location | September 2022 | VAF | January 2024 | VAF | September 2024 | VAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chr5:112175245 | SNV | APC | NM_000038.6 | p.Pro1319Ser_c.3955C>T | 5.90% | p.Pro1319Ser_c.3955C>T | 27.30% | p.Pro1319Ser_c.3955C>T | 30.20% |

| chr7:128846398 | SNV | SMO | NM_005631.5 | N.D. | p.Leu412Phe_c.1234C>T | 14.20% | N.D. | ||

| chr8:38285875 | SNV | FGFR1 | NM_001174067.1 | p.Pro179Leu_c.536C>T | 9.60% | p.Pro179Leu_c.536C>T | 21.50% | p.Pro179Leu_c.536C>T | 23.70% |

| chr9:139390794 | SNV | NOTCH1 | NM_017617.5 | p.Thr2466Met_c.7397C>T | 43.20% | p.Thr2466Met_c.7397C>T | 58.70% | p.Thr2466Met_c.7397C>T | 53.60% |

| chr17:7577094 | SNV | TP53 | NM_000546.6 | p.Arg282Trp_c.844C>T | 6.20% | p.Arg282Trp_c.844C>T | 24.90% | p.Arg282Trp_c.844C>T | 25.90% |

| chr17:7577111 | SNV | TP53 | NM_000546.6 | p.Ala276Val_c.827C>T | 6.30% | p.Ala276Val_c.827C>T | 24.60% | p.Ala276Val_c.827C>T | 25.10% |

| chr17:7578368 | MNV | TP53 | NM_000546.6 | p.Pro177Leu_c.530_531delCCInsTT | 5.90% | p.Pro177Leu_c.530_531delCCInsTT | 31% | p.Pro177Leu_c.530_531delCCInsTT | 27.50% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Papaccio, F.; Marrapodi, R.; Eibenschutz, L.; D’Arino, A.; Caputo, S.; Marini, A.; Scano, S.; Presaghi, A.; Cota, C.; Melucci, E.; et al. Resistance to SMO Inhibitors in Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Highlighting the Role of Molecular Tumor Profiling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010068

Papaccio F, Marrapodi R, Eibenschutz L, D’Arino A, Caputo S, Marini A, Scano S, Presaghi A, Cota C, Melucci E, et al. Resistance to SMO Inhibitors in Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Highlighting the Role of Molecular Tumor Profiling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010068

Chicago/Turabian StylePapaccio, Federica, Ramona Marrapodi, Laura Eibenschutz, Andrea D’Arino, Silvia Caputo, Alberto Marini, Simona Scano, Arianna Presaghi, Carlo Cota, Elisa Melucci, and et al. 2026. "Resistance to SMO Inhibitors in Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Highlighting the Role of Molecular Tumor Profiling" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010068

APA StylePapaccio, F., Marrapodi, R., Eibenschutz, L., D’Arino, A., Caputo, S., Marini, A., Scano, S., Presaghi, A., Cota, C., Melucci, E., Scalera, S., Migliano, E., Maugeri-Saccà, M., Frascione, P., & Bellei, B. (2026). Resistance to SMO Inhibitors in Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Highlighting the Role of Molecular Tumor Profiling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010068