Deletion of Glutamate Delta 1 Receptor Leads to Heterogeneous Transcription and Synaptic Gene Alterations Across Brain Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Expression Pattern of GluD1 in the Adult Mouse Brain and Generation of GluD1 Knockout Mice

2.2. Transcriptional Profiling in Each Brain Region of GluD1-KO Mice

2.3. Hippocampal Subregions Exhibit Distinct Transcriptomic Signatures in GluD1 KO Mice

2.4. GluD1 KO Neurons Exhibit Various Synapse-Related Pathways

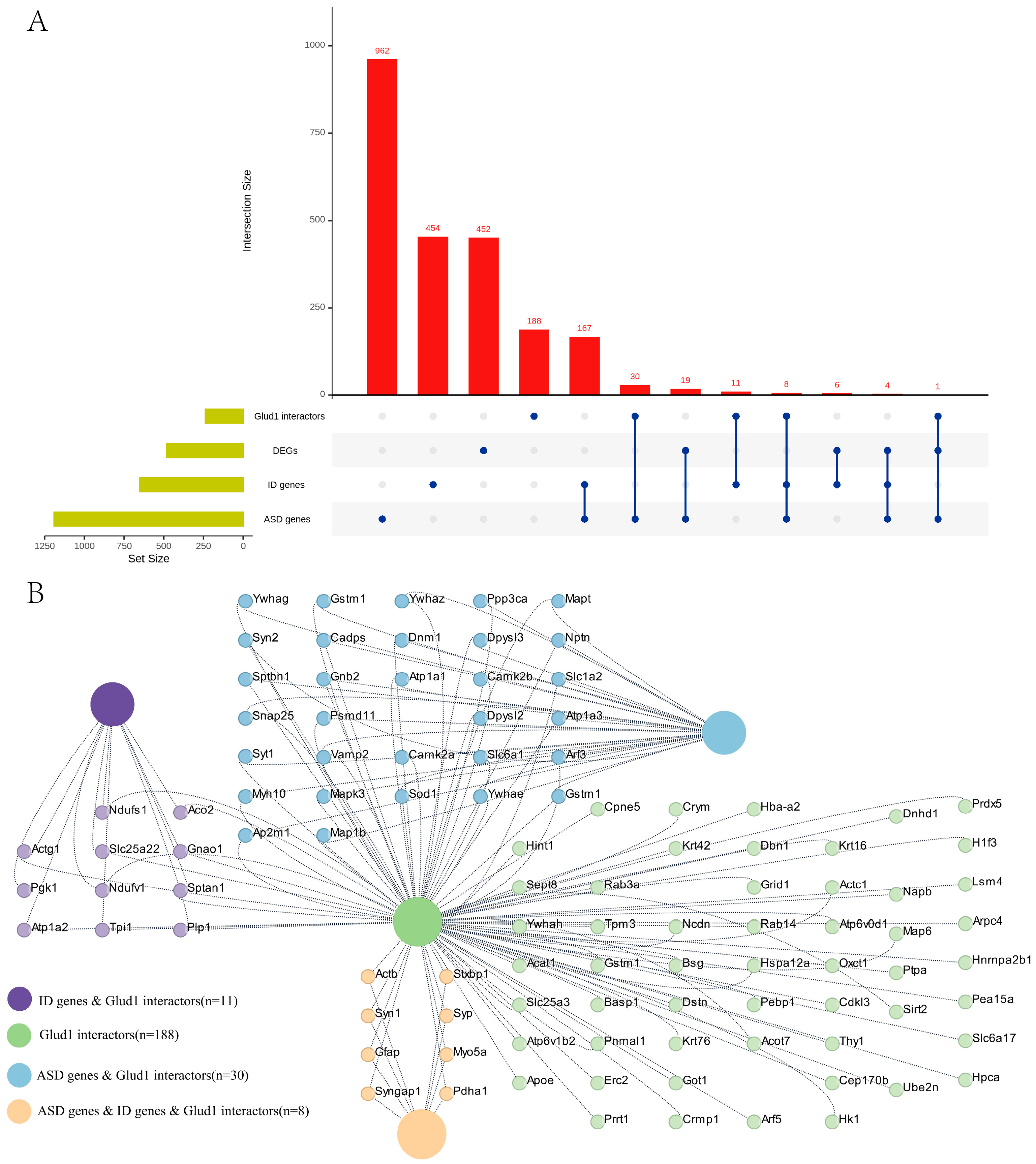

2.5. Hippocampal Proteomic Profiling Reveals GluD1 Interactors and Implicates GluD1 in ASD and ID

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Immunofluorescence

4.3. Western Blotting

4.4. Tissue Processing and Transcriptome Sequencing

4.5. Shotgun Proteomics

4.6. Co-Immunoprecipitation Assay and SDS-PAGE

4.7. Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry Analysis

4.8. Protein Identification and Annotation

4.9. Single-Cell Transcriptome Analysis

4.10. Statistics and Reproducibility

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GluD1 | glutamate delta 1 receptor |

| iGluRs | ionotropic glutamate receptors |

| ASD | autism spectrum disorder |

| ID | intellectual disability |

| SNP | single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| CNV | copy number variation |

| KO | knockout |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| MF | molecular function |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| PPI | protein–protein interaction |

| QC | quality control |

| FPKM | fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped fragments |

| ORA | over-representation analysis |

| FDR | false discovery rate |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

References

- Yamazaki, M.; Araki, K.; Shibata, A.; Mishina, M. Molecular cloning of a cDNA encoding a novel member of the mouse glutamate receptor channel family. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992, 183, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabnis, S.S.; Narasimhan, K.K.S.; Chettiar, P.B.; Shelkar, G.P.; Dravid, S.M. D-Serine disrupts Cbln1 and GluD1 interaction and affects Cbln1-dependent synaptic effects and nocifensive responses in the central amygdala. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Maison, S.F.; Wu, X.; Hirose, K.; Jones, S.M.; Bayazitov, I.; Tian, Y.; Mittleman, G.; Matthews, D.B.; Zakharenko, S.S.; et al. Orphan Glutamate Receptor δ1 Subunit Required for High-Frequency Hearing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 4500–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Díaz-Alonso, J.; Sheng, N.; Nicoll, R.A. Postsynaptic δ1 glutamate receptor assembles and maintains hippocampal synapses via Cbln2 and neurexin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E5373–E5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, R.; Hay, Y.A.; Aguado, C.; Lujan, R.; Dauphinot, L.; Potier, M.C.; Nomura, S.; Poirel, O.; El Mestikawy, S.; Lambolez, B.; et al. Glutamate receptors of the delta family are widely expressed in the adult brain. Anat. Embryol. 2014, 220, 2797–2815, Erratum in Anat. Embryol. 2014, 220, 3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, K.; Matsuda, K.; Nakamoto, C.; Uchigashima, M.; Miyazaki, T.; Yamasaki, M.; Sakimura, K.; Yuzaki, M.; Watanabe, M. Enriched Expression of GluD1 in Higher Brain Regions and Its Involvement in Parallel Fiber–Interneuron Synapse Formation in the Cerebellum. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 7412–7424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, C.; Konno, K.; Miyazaki, T.; Nakatsukasa, E.; Natsume, R.; Abe, M.; Kawamura, M.; Fukazawa, Y.; Shigemoto, R.; Yamasaki, M.; et al. Expression mapping, quantification, and complex formation of GluD1 and GluD2 glutamate receptors in adult mouse brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2019, 528, 1003–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobs, T.C.; Ben, Y.; Masland, R.H. Expression of mRNA for glutamate receptor subunits distinguishes the major classes of retinal neurons, but is less specific for individual cell types. Mol. Vis. 2007, 13, 933–948. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fossati, M.; Assendorp, N.; Gemin, O.; Colasse, S.; Dingli, F.; Arras, G.; Loew, D.; Charrier, C. Trans-Synaptic Signaling through the Glutamate Receptor Delta-1 Mediates Inhibitory Synapse Formation in Cortical Pyramidal Neurons. Neuron 2019, 104, 1081–1094.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Patzke, C.; Liakath-Ali, K.; Seigneur, E.; Südhof, T.C. GluD1 is a signal transduction device disguised as an ionotropic receptor. Nature 2021, 595, 261–265, Erratum in Nature 2025, 642, E27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piot, L.; Heroven, C.; Bossi, S.; Zamith, J.; Malinauskas, T.; Johnson, C.; Wennagel, D.; Stroebel, D.; Charrier, C.; Aricescu, A.R.; et al. GluD1 binds GABA and controls inhibitory plasticity. Science 2023, 382, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Hillman, B.G.; Gupta, S.C.; Suryavanshi, P.; Bhatt, J.M.; Pavuluri, R.; Stairs, D.J.; Dravid, S.M. Deletion of Glutamate Delta-1 Receptor in Mouse Leads to Enhanced Working Memory and Deficit in Fear Conditioning. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawande, D.Y.; Narasimhan, K.K.S.; Bhatt, J.M.; Pavuluri, R.; Kesherwani, V.; Suryavanshi, P.S.; Shelkar, G.P.; Dravid, S.M. Glutamate delta 1 receptor regulates autophagy mechanisms and affects excitatory synapse maturation in the somatosensory cortex. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 178, 106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallin, M.D.; Lasseter, V.K.; Avramopoulos, D.; Nicodemus, K.K.; Wolyniec, P.S.; McGrath, J.A.; Steel, G.; Nestadt, G.; Liang, K.-Y.; Huganir, R.L.; et al. Bipolar I Disorder and Schizophrenia: A 440–Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism Screen of 64 Candidate Genes among Ashkenazi Jewish Case-Parent Trios. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 77, 918–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.-Z.; Huang, K.; Shi, Y.-Y.; Tang, W.; Zhou, J.; Feng, G.-Y.; Zhu, S.-M.; Liu, H.-J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, X.-D.; et al. A Case-control association study between the GRID1 gene and schizophrenia in the Chinese Northern Han population. Schizophr. Res. 2007, 93, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treutlein, J.; Mühleisen, T.W.; Frank, J.; Mattheisen, M.; Herms, S.; Ludwig, K.U.; Treutlein, T.; Schmael, C.; Strohmaier, J.; Böβhenz, K.V.; et al. Dissection of phenotype reveals possible association between schizophrenia and Glutamate Receptor Delta 1 (GRID1) gene promoter. Schizophr. Res. 2009, 111, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, A.J.; Ma, D.; Cukier, H.N.; Nations, L.D.; Schmidt, M.A.; Chung, R.-H.; Jaworski, J.M.; Salyakina, D.; Konidari, I.; Whitehead, P.L.; et al. Evaluation of copy number variations reveals novel candidate genes in autism spectrum disorder-associated pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 3513–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balciuniene, J.; Feng, N.; Iyadurai, K.; Hirsch, B.; Charnas, L.; Bill, B.R.; Easterday, M.C.; Staaf, J.; Oseth, L.; Czapansky-Beilman, D.; et al. Recurrent 10q22-q23 Deletions: A Genomic Disorder on 10q Associated with Cognitive and Behavioral Abnormalities. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 80, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, D.C.; Pietrancosta, N.; Badillo, E.B.; Raux, B.; Tapken, D.; Zlatanovic, A.; Doridant, A.; Pode-Shakked, B.; Raas-Rothschild, A.; Elpeleg, O.; et al. GRID1/GluD1 homozygous variants linked to intellectual disability and spastic paraplegia impair mGlu1/5 receptor signaling and excitatory synapses. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 1205–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.N.; Yi, Q.; Krumm, N.; Huddleston, J.; Hoekzema, K.; Stessman, H.A.F.; Doebley, A.-L.; Bernier, R.A.; Nickerson, D.A.; Eichler, E.E. denovo-db: A compendium of human de novo variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D804–D811. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, R.; Gupta, S.C.; Hillman, B.G.; Bhatt, J.M.; Stairs, D.J.; Dravid, S.M. Deletion of Glutamate Delta-1 Receptor in Mouse Leads to Aberrant Emotional and Social Behaviors. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, C.; Kawamura, M.; Nakatsukasa, E.; Natsume, R.; Takao, K.; Watanabe, M.; Abe, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Sakimura, K. GluD1 knockout mice with a pure C57BL/6N background show impaired fear memory, social interaction, and enhanced depressive-like behavior. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Bendl, J.; Rahman, S.; Vicari, J.M.; Coleman, C.; Clarence, T.; Latouche, O.; Tsankova, N.M.; Li, A.; Brennand, K.J.; et al. Multi-omic profiling of the developing human cerebral cortex at the single-cell level. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, T.; Mori, H.; Mishina, M. Direct interaction of GluRδ2 with Shank scaffold proteins in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2004, 26, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cembrowski, M.S.; Bachman, J.L.; Wang, L.; Sugino, K.; Shields, B.C.; Spruston, N. Spatial Gene-Expression Gradients Underlie Prominent Heterogeneity of CA1 Pyramidal Neurons. Neuron 2016, 89, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; van Velthoven, C.T.; Nguyen, T.N.; Goldy, J.; Sedeno-Cortes, A.E.; Baftizadeh, F.; Bertagnolli, D.; Casper, T.; Chiang, M.; Crichton, K.; et al. A taxonomy of transcriptomic cell types across the isocortex and hippocampal formation. Cell 2021, 184, 3222–3241.e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahams, B.S.; Arking, D.E.; Campbell, D.B.; Mefford, H.C.; Morrow, E.M.; Weiss, L.A.; Menashe, I.; Wadkins, T.; Banerjee-Basu, S.; Packer, A. SFARI Gene 2.0: A community-driven knowledgebase for the autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Mol. Autism 2013, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochinke, K.; Zweier, C.; Nijhof, B.; Fenckova, M.; Cizek, P.; Honti, F.; Keerthikumar, S.; Oortveld, M.A.; Kleefstra, T.; Kramer, J.M.; et al. Systematic Phenomics Analysis Deconvolutes Genes Mutated in Intellectual Disability into Biologically Coherent Modules. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 98, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomeli, H.; Sprengel, R.; Laurie, D.; Köhr, G.; Herb, A.; Seeburg, P.; Wisden, W. The rat delta-1 and delta-2 subunits extend the excitatory amino acid receptor family. FEBS Lett. 1993, 315, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pessoa, L.; Medina, L.; Hof, P.R.; Desfilis, E. Neural architecture of the vertebrate brain: Implications for the interaction between emotion and cognition. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 107, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Essen, D.C.; Glasser, M.F. Parcellating Cerebral Cortex: How Invasive Animal Studies Inform Noninvasive Mapmaking in Humans. Neuron 2018, 99, 640–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Economo, M.N.; Komiyama, T.; Kubota, Y.; Schiller, J. Learning and Control in Motor Cortex across Cell Types and Scales. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e1233242024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; van Beugen, B.J.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Distributed synergistic plasticity and cerebellar learning. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 619–635, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, S.B.E.; Ko, R.; Ölveczky, B.P. Distinct roles for motor cortical and thalamic inputs to striatum during motor skill learning and execution. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabk0231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Parras, M.-T.; Safaie, M.; Sarno, S.; Louis, J.; Karoutchi, C.; Berret, B.; Robbe, D. The Dorsal Striatum Energizes Motor Routines. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 4362–4372.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, S.A.; Siddiqui, T.J. Synapse organizers as molecular codes for synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2023, 46, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Matúš, D.; Südhof, T.C. Reconstitution of synaptic junctions orchestrated by teneurin-latrophilin complexes. Science 2025, 387, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oostrum, M.; Schuman, E.M. Understanding the molecular diversity of synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2025, 26, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benamer, N.; Marti, F.; Lujan, R.; Hepp, R.; Aubier, T.G.; Dupin, A.A.M.; Frébourg, G.; Pons, S.; Maskos, U.; Faure, P.; et al. GluD1, linked to schizophrenia, controls the burst firing of dopamine neurons. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 23, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantz, S.C.; Moussawi, K.; Hake, H.S. Delta glutamate receptor conductance drives excitation of mouse dorsal raphe neurons. eLife 2020, 9, e56054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.C.; Yadav, R.; Pavuluri, R.; Morley, B.J.; Stairs, D.J.; Dravid, S.M. Essential role of GluD1 in dendritic spine development and GluN2B to GluN2A NMDAR subunit switch in the cortex and hippocampus reveals ability of GluN2B inhibition in correcting hyperconnectivity. Neuropharmacology 2015, 93, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Shelkar, G.P.; Gandhi, P.J.; Gawande, D.Y.; Hoover, A.; Villalba, R.M.; Pavuluri, R.; Smith, Y.; Dravid, S.M. Striatal glutamate delta-1 receptor regulates behavioral flexibility and thalamostriatal connectivity. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 137, 104746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, D.Y.; Shelkar, G.P.; Liu, J.; Ayala, A.D.; Pavuluri, R.; Choi, D.; Smith, Y.; Dravid, S.M. Glutamate Delta-1 Receptor Regulates Inhibitory Neurotransmission in the Nucleus Accumbens Core and Anxiety-Like Behaviors. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 4787–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Gandhi, P.J.; Pavuluri, R.; Shelkar, G.P.; Dravid, S.M. Glutamate delta-1 receptor regulates cocaine-induced plasticity in the nucleus accumbens. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; You, H.; Mizui, T.; Ishikawa, Y.; Takao, K.; Miyakawa, T.; Li, X.; Bai, T.; Xia, K.; Zhang, L.; et al. Inhibiting proBDNF to mature BDNF conversion leads to ASD-like phenotypes in vivo. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 3462–3474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexrode, L.E.; Hartley, J.; Showmaker, K.C.; Challagundla, L.; Vandewege, M.W.; Martin, B.E.; Blair, E.; Bollavarapu, R.; Antonyraj, R.B.; Hilton, K.; et al. Molecular profiling of the hippocampus of children with autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 1968–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sisqués, L.; Bhatt, S.U.; Matuleviciute, R.; Gileadi, T.E.; Kramar, E.; Graham, A.; Garcia, F.G.; Keiser, A.; Matheos, D.P.; Cain, J.A.; et al. The Intellectual Disability Risk GeneKdm5bRegulates Long-Term Memory Consolidation in the Hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e1544232024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.A.; Muralidhar, S.; Wang, Z.; Cervantes, D.C.; Basu, R.; Taylor, M.R.; Hunter, J.; Cutforth, T.; Wilke, S.A.; Ghosh, A.; et al. The intellectual disability gene Kirrel3 regulates target-specific mossy fiber synapse development in the hippocampus. eLife 2015, 4, e09395, Erratum in eLife 2016, 5, e18706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.C.; Li, L.; Zhang, M.; Li, W.B.; Li, Q.J.; Zhao, L. Division of CA1, CA3 and DG regions of the hippocampus of Wistar rat. Chin. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 28, 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Q.; Zeng, M.; Wu, X.; Wu, H.; Zhan, Y.; Tian, R.; Zhang, M. CaMKIIα-driven, phosphatase-checked postsynaptic plasticity via phase separation. Cell Res. 2020, 31, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, J.; Liao, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, G.; De, Y.; Shangguan, H.; Tao, W. Deletion of Glutamate Delta 1 Receptor Leads to Heterogeneous Transcription and Synaptic Gene Alterations Across Brain Regions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010067

Huang J, Liao J, Chen X, Lin G, De Y, Shangguan H, Tao W. Deletion of Glutamate Delta 1 Receptor Leads to Heterogeneous Transcription and Synaptic Gene Alterations Across Brain Regions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010067

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Jingguo, Jiahao Liao, Xuanying Chen, Guiping Lin, Yangwangmu De, Huakun Shangguan, and Wucheng Tao. 2026. "Deletion of Glutamate Delta 1 Receptor Leads to Heterogeneous Transcription and Synaptic Gene Alterations Across Brain Regions" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010067

APA StyleHuang, J., Liao, J., Chen, X., Lin, G., De, Y., Shangguan, H., & Tao, W. (2026). Deletion of Glutamate Delta 1 Receptor Leads to Heterogeneous Transcription and Synaptic Gene Alterations Across Brain Regions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010067