Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Solidago canadensis L. Essential Oil and Its Antifungal Mechanism Against Mulberry Sclerotinia Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. EO Yield and Composition of Different Parts of S. canadensis L.

2.1.1. SLEO Yields

2.1.2. SLEO Composition

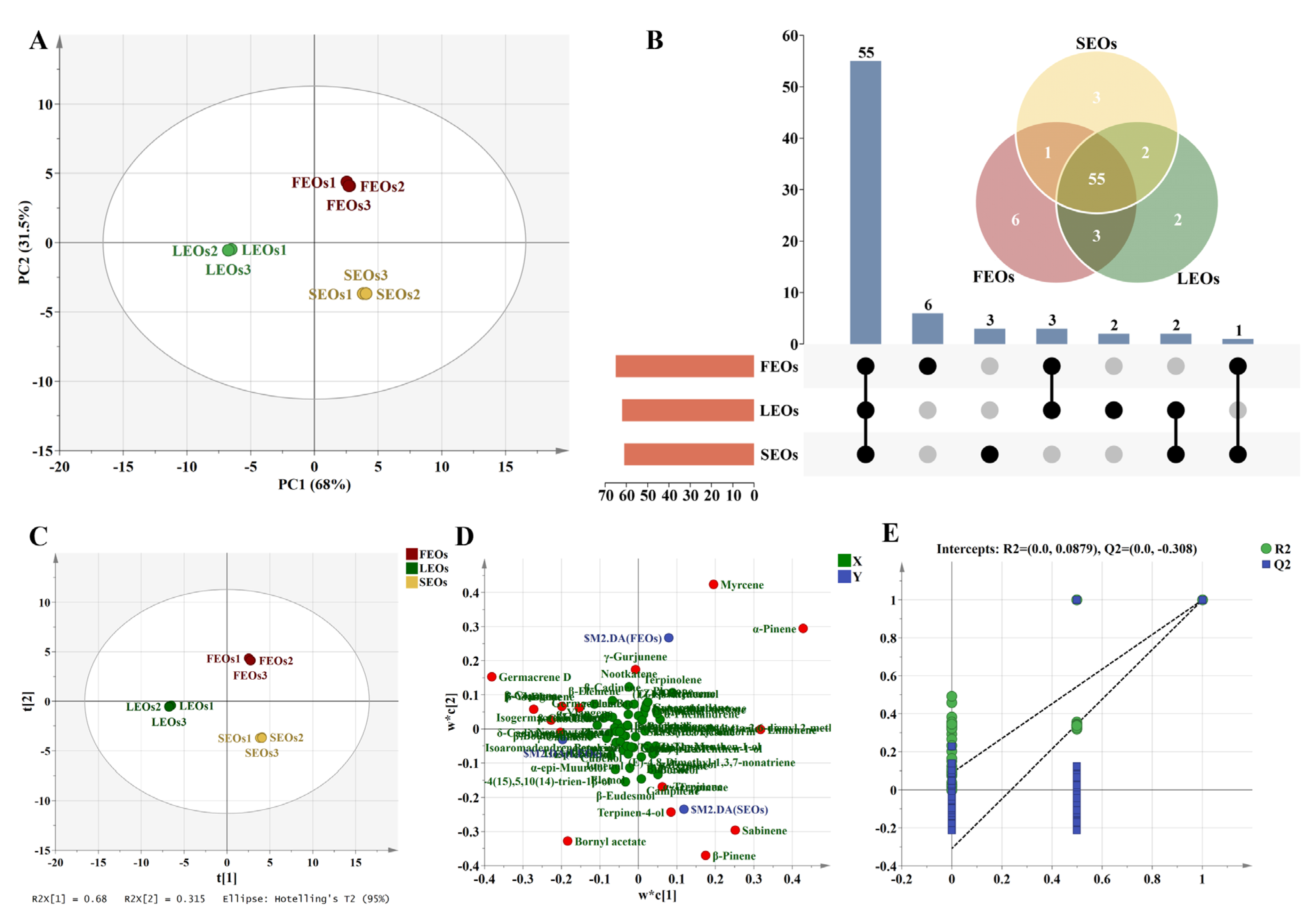

2.2. Multivariate Statistical Analyses of SLEOs

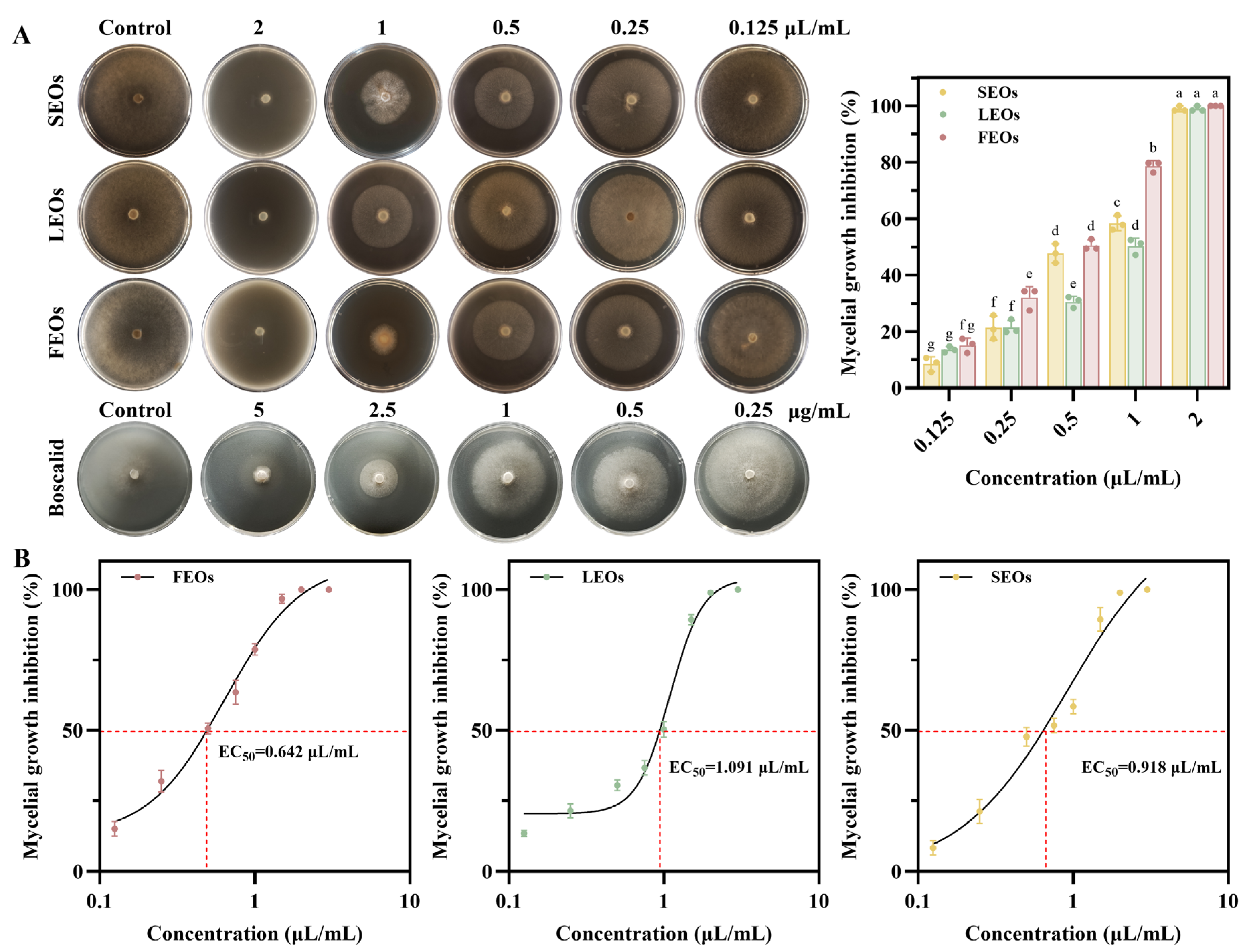

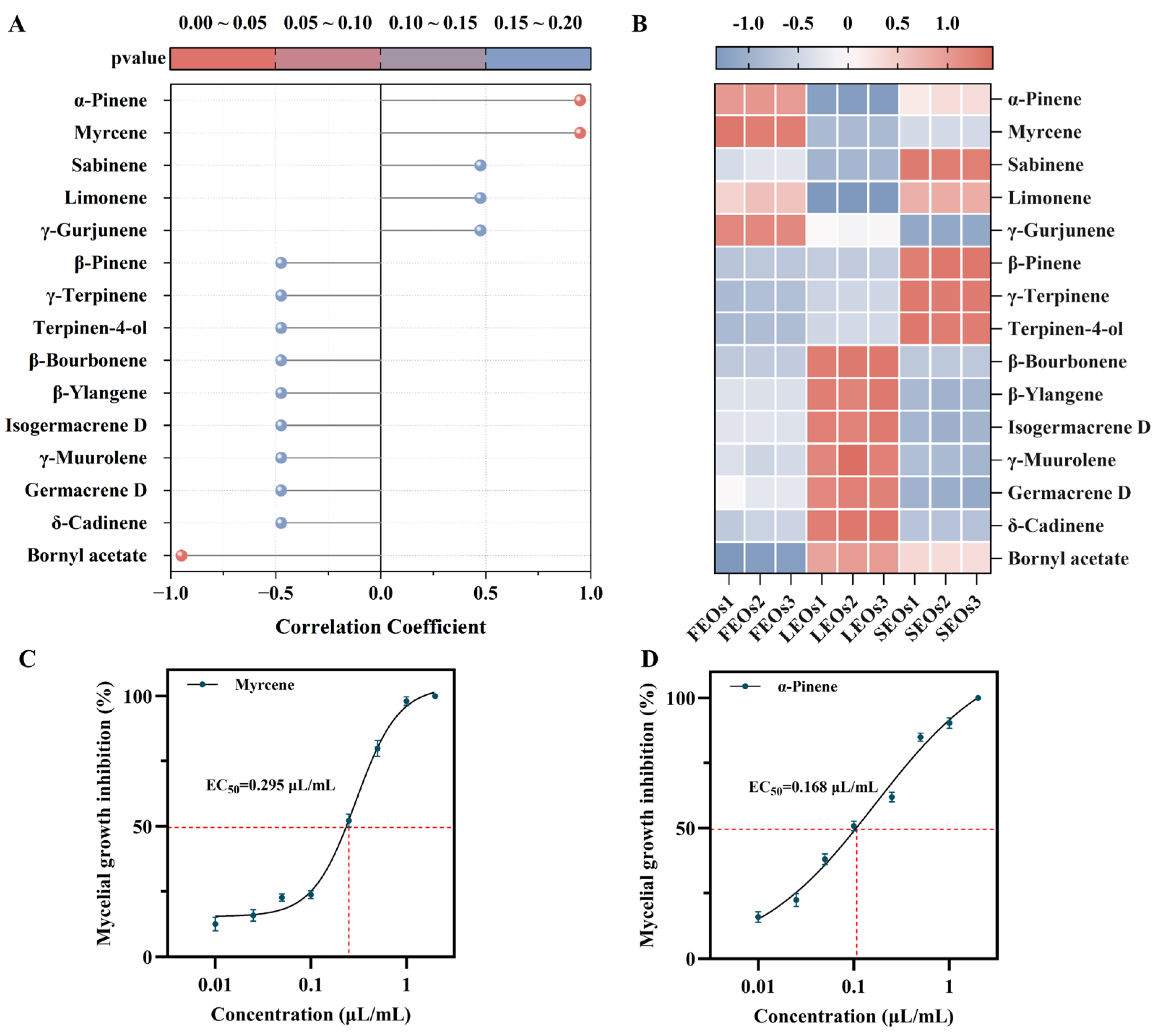

2.3. Antifungal Activity of SLEOs

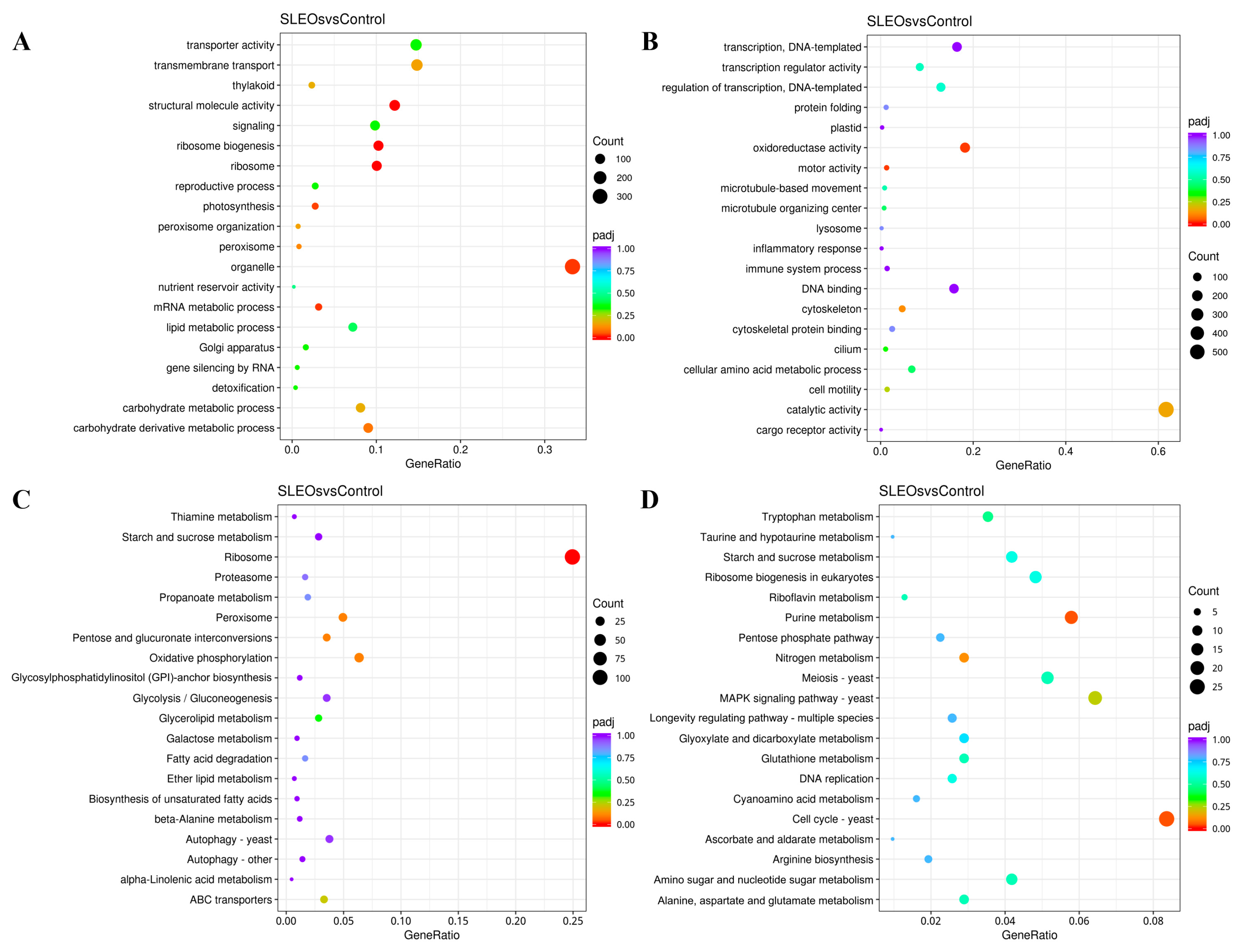

2.4. Antifungal Mechanism of FEOs Based on Transcriptomics

2.4.1. Transcriptomics

2.4.2. Effects of FEOs on Morphology and Ultrastructure of C. shiraiana

2.4.3. Effects of FEOs on Cell Wall of C. shiraiana

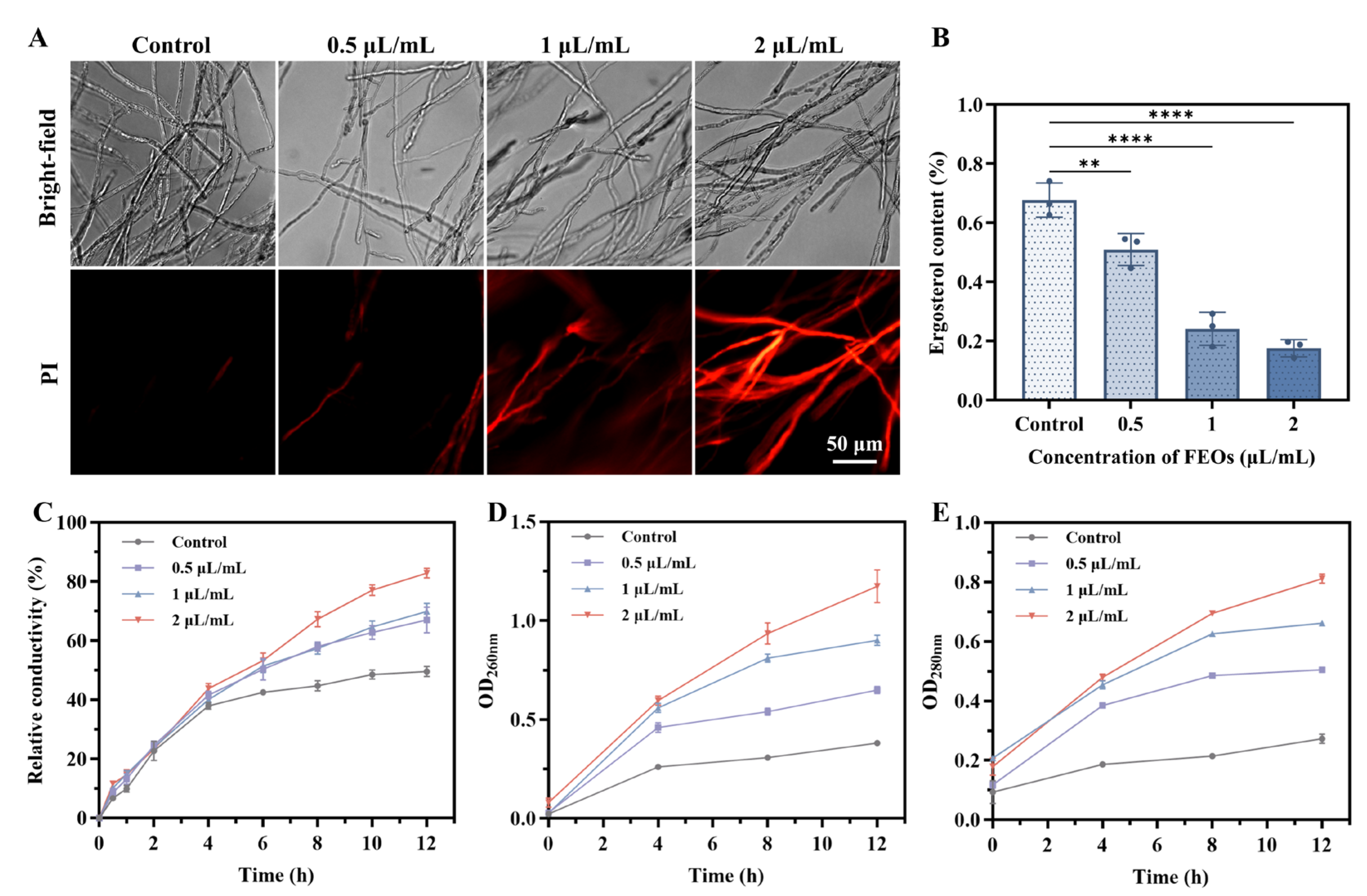

2.4.4. Effects of FEOs on Cell Membrane of C. shiraiana

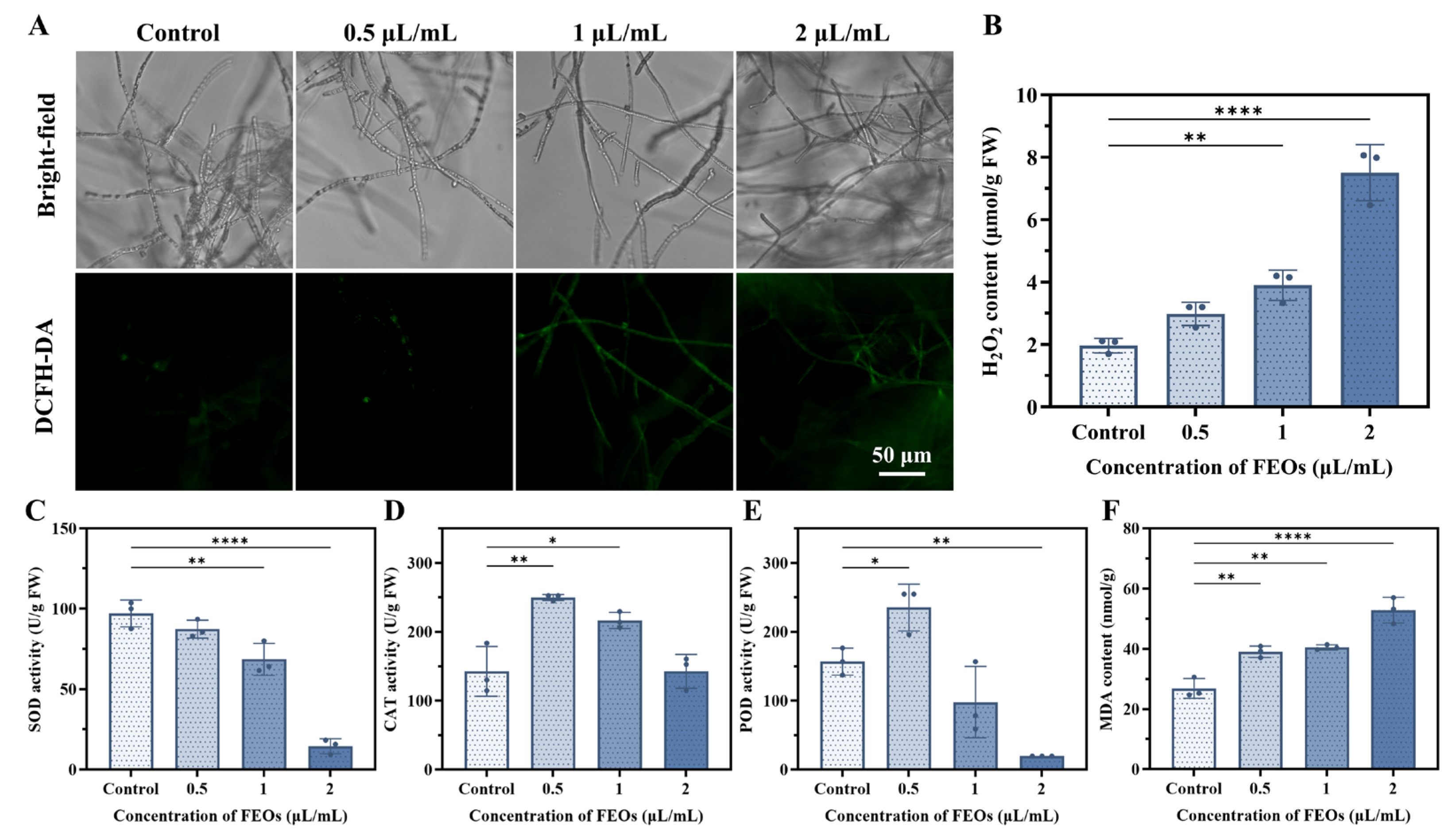

2.4.5. Effects of FEOs on Endogenous ROS and Oxidative Damage of C. shiraiana

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Chemicals

3.2. Extraction of SLEOs

3.3. Chromatographic Analysis

3.4. Antifungal Activity of Different Plant Part EOs of S. canadensis L. In Vitro

3.5. Transcriptomic Analysis

3.6. Observation of Mycelium Morphology and Ultrastructure

3.7. Effect on Cell Wall of C. shiraiana

3.8. Effect on ROS and Oxidoreductase Activity of C. shiraiana

3.9. Effect on Cell Membrane of C. shiraiana

3.10. Effect on DNA Damage of C. shiraiana

3.11. Statistical Analyses

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stukenbrock, E.; Gurr, S. Address the growing urgency of fungal disease in crops. Nature 2023, 617, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.C.; Gardea-Torresdey, J. Achieving food security through the very small. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 627–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.F.; Tedersoo, L.; Crowther, T.W.; Wang, B.Z.; Shi, Y.; Kuang, L.; Li, T.; Wu, M.; Liu, M.; Luan, L.; et al. Global diversity and biogeography of potential phytopathogenic fungi in a changing world. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Q.; Chen, Z.; He, T.; Yu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Nan, H.; Huang, Q.; Zhao, T. Anti-skin aging effects of mulberry fruit extracts: In vitro and in vivo evaluations of the anti-glycation and antioxidant activities. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 112, 105984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.P.; Pham, T.V.; Weina, K.; Tran, T.N.H.; Vo, L.V.; Nguyen, P.T.; Bui, T.L.H.; Phan, T.H.; Nguyen, D.Q. Green extraction of phenolics and flavonoids from black mulberry fruit using natural deep eutectic solvents: Optimization and surface morphology. BMC Chem. 2023, 17, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yu, W.S.; Chen, G.; Meng, S.; Xiang, Z.H.; He, N.J. Antinociceptive and Antibacterial Properties of Anthocyanins and Flavonols from Fruits of Black and Non-Black Mulberries. Molecules 2018, 23, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Hu, X.M.; Deng, W.; Li, Y.; Han, G.M.; Ye, C.H. Soil fungal community comparison of different mulberry genotypes and the relationship with mulberry fruit sclerotiniosis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Liu, S.M.; Xu, Y.Z.; Liu, C.Y.; Zhu, P.P.; Zhang, S.; Xia, Z.Q.; Zhao, A.C. Stigma type and transcriptome analyses of mulberry revealed the key factors associated with Ciboria shiraiana resistance. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 200, 107743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.X.; Wang, Y.H.; Yang, G.L.; Wang, Y.H.; Liu, F.Q.; Chen, C. A review of cumulative risk assessment of multiple pesticide residues in food: Current status, approaches and future perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 144, 104340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rhijn, N.; Rhodes, J. Evolution of antifungal resistance in the environment. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 1804–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabarwal, A.; Kumar, K.; Singh, R.P. Hazardous effects of chemical pesticides on human health-Cancer and other associated disorders. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 63, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondareva, L.; Fedorova, N. Pesticides: Behavior in Agricultural Soil and Plants. Molecules 2021, 26, 5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, F.; Brown, Z.S.; Kuzma, J. Wicked evolution: Can we address the sociobiological dilemma of pesticide resistance? Science 2018, 360, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Lu, J.Z.; Zhang, W.J.; Chen, J.K.; Li, B. Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis): An invasive alien weed rapidly spreading in China. Acta Phytotaxon. Sin. 2006, 44, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhilasha, D.; Quintana, N.; Vivanco, J.; Joshi, J. Do allelopathic compounds in invasive Solidago canadensis s.l. restrain the native European flora? J. Ecol. 2008, 96, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.G.; Wang, B.; Zhang, S.S.; Tang, J.J.; Tu, C.; Hu, S.J.; Yong, J.W.H.; Chen, X. Enhanced allelopathy and competitive ability of invasive plant Solidago canadensis in its introduced range. J. Plant Ecol. 2013, 6, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S.; Jin, Y.L.; Tang, J.J.; Chen, X. The invasive plant Solidago canadensis L. suppresses local soil pathogens through allelopathy. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2009, 41, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljuha, D.; Sladonja, B.; Bozac, M.U.; Sola, I.; Damijanic, D.; Weber, T. The Invasive Alien Plant Solidago canadensis: Phytochemical Composition, Ecosystem Service Potential, and Application in Bioeconomy. Plants 2024, 13, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzlovar, S.; Janes, D.; Koce, J.D. The Effect of Extracts and Essential Oil from Invasive Solidago spp. and Fallopia japonica on Crop-Borne Fungi and Wheat Germination. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 58, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Song, M.N.; Sun, Y.L.; Yang, F.Y.; Yu, H.N.; Wu, C.; Sun, Y.L.; Chang, W.Q.; Ge, D.; Zhang, H. Antifungal and Allelopathic Activities of Sesquiterpenes from Solidago canadensis. Curr. Org. Chem. 2021, 25, 2676–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzlovar, S.; Koce, J.D. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity of Aqueous and Organic Extracts from Indigenous and Invasive Species of Goldenrod (Solidago spp.) Grown in Slovenia. Phyton-Ann. Rei Bot. 2014, 54, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Apati, P.; Szentmihályi, K.; Balázs, A.; Baumann, D.; Hamburger, M.; Kristó, T.S.; Szőke, É.; Kéry, Á. HPLC Analysis of the flavonoids in pharmaceutical preparations from canadian goldenrod (Solidago canadensis). Chromatographia 2002, 56, S65–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzelac Božac, M.; Poljuha, D.; Dudaš, S.; Bilić, J.; Šola, I.; Mikulič-Petkovšek, M.; Sladonja, B. Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity of Invasive Solidago canadensis L.: Potential Applications in Phytopharmacy. Plants 2024, 14, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purmalis, O.; Klavins, L.; Niedrite, E.; Mezulis, M.; Klavins, M. Invasive Plants as a Source of Polyphenols with High Radical Scavenging Activity. Plants 2025, 14, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gala-Czekaj, D.; Dziurka, M.; Bocianowski, J.; Synowiec, A. Autoallelopathic potential of aqueous extracts from Canadian goldenrod (Solidago canadensis L.) and giant goldenrod (S. gigantea Aiton). Acta Physiol. Plant. 2021, 44, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulino, B.N.; Silva, G.N.S.; Araújo, F.F.; Néri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M.; Bicas, J.L.; Molina, G. Beyond natural aromas: The bioactive and technological potential of monoterpenes. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 128, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrignani, F.; Siroli, L.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Gardini, F.; Lanciotti, R. Innovative strategies based on the use of essential oils and their components to improve safety, shelf-life and quality of minimally processed fruits and vegetables. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 46, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Xu, Y.Q.; Xiao, H.; Mariga, A.M.; Chen, Y.P.; Zhang, X.C.; Wang, L.; Li, D.; Li, L.; Luo, Z.S. Rethinking of botanical volatile organic compounds applied in food preservation: Challenges in acquisition, application, microbial inhibition and stimulation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 125, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavela, R.; Benelli, G. Essential Oils as Ecofriendly Biopesticides? Challenges and Constraints. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Střelková, T.; Jurkaninová, L.; Bušinová, A.; Nový, P.; Klouček, P. Essential oils in vapour phase as antifungal agents in the cereal processing chain. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthil-Nathan, S. A Review of Resistance Mechanisms of Synthetic Insecticides and Botanicals, Phytochemicals, and Essential Oils as Alternative Larvicidal Agents Against Mosquitoes. Front. Physiol. 2020, 10, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Shao, X.F.; Wei, Y.Z.; Li, Y.H.; Xu, F.; Wang, H.F. Solidago canadensis L. Essential Oil Vapor Effectively Inhibits Botrytis cinerea Growth and Preserves Postharvest Quality of Strawberry as a Food Model System. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Grul’ová, D.; Baranová, B.; Caputo, L.; De Martino, L.; Sedlák, V.; Camele, I.; De Feo, V. Antimicrobial Activity and Chemical Composition of Essential Oil Extracted from Solidago canadensis L. Growing Wild in Slovakia. Molecules 2019, 24, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Jiang, K.; Liu, J.; Zhou, J.W.; Wu, B.D. Moderate and heavy Solidago canadensis L. invasion are associated with decreased taxonomic diversity but increased functional diversity of plant communities in East China. Ecol. Eng. 2018, 112, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Hafeez, A.; Zhang, T.T.; Rao, M.J.; Li, S.C.; Cai, K.Z. Silicon-modified Solidago canadensis L. biochar suppresses soilborne disease and improves soil quality. Biochar 2025, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalemba, D.; Góra, J.; Kurowska, A. Analysis of the Essential Oil of Solidago canadensis. Planta Medica 2007, 56, 222–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Lei, Y.; Qin, L.; Liu, J. Chemical Composition and Cytotoxic Activities of the Essential Oil from the Inflorescences of Solidago canadensis L., an Invasive Weed in Southeastern China. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2012, 15, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherei, M.; Khaleel, A.; Motaal, A.A.; Abd-Elbaki, P. Effect of Seasonal Variation on the Composition of the Essential Oil of Solidago canadensis Cultivated in Egypt. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2014, 17, 891–898. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.M.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Song, H.E.; Kim, I.S.; Seo, W.D.; Lee, J.H.; Oh, S.R.; Lee, D.Y.; Ryu, H.W. Comparisons of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activities during different growth stages in Artemisia gmelinii Weber ex Stechm with UPLC-QTOF/MS based on a metabolomics approach. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 202, 116999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.Z.; Lin, S.Y.; Li, X.R.; Li, D.M. Different stages of flavor variations among canned Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba): Based on GC-IMS and PLS-DA. Food Chem. 2024, 459, 140465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Y. Rapid and accurate identification of Dendrobium species using FT-IR, FT-NIR, and data fusion with machine learning. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 234, 121637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.P.; Kang, J.M.; Yang, R.; Li, H.; Cui, H.X.; Bai, H.T.; Tsitsilin, A.; Li, J.Y.; Shi, L. Multidimensional exploration of essential oils generated via eight oregano cultivars: Compositions, chemodiversities, and antibacterial capacities. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Singh, V.K.; Dwivedy, A.K.; Chaudhari, A.K.; Dubey, N.K. Exploration of some potential bioactive essential oil components as green food preservative. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 137, 110498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Upadhyay, S.; Erdogan Orhan, I.; Kumar Jugran, A.; Jayaweera, S.L.D.; Dias, D.A.; Sharopov, F.; Taheri, Y.; Martins, N.; Baghalpour, N.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of α- and β-Pinene: A Miracle Gift of Nature. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite-Andrade, M.C.; Neto, L.N.D.; Buonafina-Paz, M.D.S.; dos Santos, F.D.G.; Alves, A.I.D.; de Castro, M.C.A.B.; Mori, E.; de Lacerda, B.C.G.V.; Araújo, I.M.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; et al. Antifungal Effect and Inhibition of the Virulence Mechanism of D-Limonene against Candida parapsilosis. Molecules 2022, 27, 8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Sun, J.Y.; Zhao, S.H.; Zhang, F.; Meng, X.H.; Liu, B.J. Highly stable nanostructured lipid carriers containing candelilla wax for D-limonene encapsulation: Preparation, characterization and antifungal activity. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 145, 109101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lin, Z.X.; Xiang, W.L.; Huang, M.; Tang, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Q.H.; Zhang, Q.; Rao, Y.; Liu, L. Antifungal activity and mechanism of d-limonene against foodborne opportunistic pathogen Candida tropicalis. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 159, 113144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judžentienė, A. Compositional Variability of Essential Oils and Their Bioactivity in Native and Invasive Erigeron Species. Molecules 2025, 30, 2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovelli, F.; Romeo, A.; Lattanzio, P.; Ammendola, S.; Battistoni, A.; La Frazia, S.; Vindigni, G.; Unida, V.; Biocca, S.; Gaziano, R.; et al. Deciphering the Broad Antimicrobial Activity of Melaleuca alternifolia Tea Tree Oil by Combining Experimental and Computational Investigations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Połeć, K.; Broniatowski, M.; Wydro, P.; Hąc-Wydro, K. The impact of β-myrcene—The main component of the hop essential oil—On the lipid films. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 308, 113028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohzaki, K.; Gomi, K.; Yamasaki-Kokudo, Y.; Ozawa, R.; Takabayashi, J.; Akimitsu, K. Characterization of a sabinene synthase gene from rough lemon (Citrus jambhiri). J. Plant Physiol. 2009, 166, 1700–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wu, B.; Wu, C.H.; Chen, Q.; Niu, Y.F.; Shi, Z.J.; Liang, K.; Rao, X.P. Acrylpimaric acid-modified chitosan derivatives as potential antifungal agents against. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 352, 123244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.B.; Zhao, Z.M.; Ma, Y.; Li, A.P.; Zhang, Z.J.; Hu, Y.M.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, R.; Luo, X.F.; Zhang, B.Q.; et al. Antifungal activity and preliminary mechanism of pristimerin against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 185, 115124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.L.; Zhang, B.Q.; Luo, X.F.; Li, A.P.; Zhang, S.Y.; An, J.X.; Zhang, Z.J.; Liu, Y.Q. Antifungal efficacy of sixty essential oils and mechanism of oregano essential oil against Rhizoctonia solani. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 191, 115975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xu, X.; Mao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Huang, M. Characterization, vapor release behavior, vapor bio-functional performance and application of UV-responded modified polyvinyl alcohol bio-active films loaded with oregano essential oil microcapsules. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 47, 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Z.; Wang, H.X.; Wu, C.N.; Bao, L.J.; Su, C.; Qian, Y.H. The effectiveness of Star Anise and Clove Essential Oils against Mulberry Sclerotia and Field Efficacy Test of Their Preparations. North Seric. 2022, 43, 36–39. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.X.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Z.B.; Li, D.B.; Zhou, L.; Wang, H.J.; Lan, F.J.; Liu, X.F. Screening of Eco-Friendly Agents for the Control of Mulberry Sclerotinia Diseases. China Seric. 2022, 43, 4–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Grazzini, A.; Cavanaugh, A.M. Fungal microtubule organizing centers are evolutionarily unstable structures. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2024, 172, 103885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, G. Tracks for traffic: Microtubules in the plant pathogen Ustilago maydis. New Phytol. 2007, 174, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; He, K.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.H.; Qian, L.; Gao, X.H.; Liu, S.M. Transcriptional dynamics of Fusarium pseudograminearum under high fungicide stress and the important role of FpZRA1 in fungal pathogenicity and DON toxin production. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, P.; Cong, W.; Ma, N.; Zhou, M.; Hou, Y. The transcription factor FgCreA modulates ergosterol biosynthesis and sensitivity to DMI fungicides by regulating transcription of FgCyp51A and FgErg6A in Fusarium graminearum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 284, 137903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.Q.; Li, Y.L.; Gu, S.Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, G.P.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhang, X.H.; Liu, J.L.; Pan, H.Y. Transcription Repressor SsGATA2 Regulates Broad-Spectrum Resistance to Fungicides and Pathogenicity in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 16787–16803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Lv, Y.; Wu, R.Z.; Yu, Z.W.; Liang, Y.L.; Yu, Z.C.; Liang, R.B.; Tang, L.F.; Chen, H.Y.; Fan, Z.J. Fungicidal Activity of Novel 6-Isothiazol-5-ylpyrimidin-4-amine-Containing Compounds Targeting Complex I Reduced Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Oxidoreductase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 22082–22091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oide, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Watanabe, A.; Inui, M. Carbohydrate-binding property of a cell wall integrity and stress response component (WSC) domain of an alcohol oxidase from the rice blast pathogen Pyricularia oryzae. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2019, 125, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.; Chau, M.Q.; Hoang, C.V.; Chandrasekharan, N.; Bhaskar, C.; Ma, L.S. Fungal Cell Wall-Associated Effectors: Sensing, Integration, Suppression, and Protection. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2024, 37, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.D.; Qi, H.T.; Liu, H.; Yuan, F.H.; Yang, C.; Liu, T. Two Birds with One Stone: Eco-Friendly Nano-Formulation Endows a Commercial Fungicide with Excellent Insecticidal Activity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2420401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Li, Y.; He, W.; Chen, T.; Liu, N.; Ma, L.; Qiu, Z.; Shang, Z.; Wang, Z. A polyene macrolide targeting phospholipids in the fungal cell membrane. Nature 2025, 640, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.X.; Li, Q.Q.; Jia, W.L.; Shang, H.P.; Zhao, J.; Hao, Y.; Li, C.Y.; Tomko, M.; Zuverza-Mena, N.; Elmer, W.; et al. Role of Nanoscale Hydroxyapatite in Disease Suppression of Fusarium-Infected Tomato. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 13465–13476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.Z.; Gao, K.; Yu, H.H.; Liu, W.X.; Qin, Y.K.; Xing, R.E.; Liu, S.; Li, P.C. C-coordinated O-carboxymethyl chitosan Cu(II) complex exerts antifungal activity by disrupting the cell membrane integrity of Phytophthora capsici Leonian. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 261, 117821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.P.; Chen, H.Y.; Du, P.R.; Miao, X.R.; Huang, S.Q.; Cheng, D.M.; Xu, H.H.; Zhang, Z.X. Inhibition mechanism of Rhizoctonia solani by pectin-coated iron metal-organic framework nanoparticles and evidence of an induced defense response in rice. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 474, 134807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.J.; Romanov, K.A.; Jian, J.F.; Swaby, L.C.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Guan, I.; Thomas, S.M.; Olive, A.J.; O’Connor, T.J. Bacterial pathogens hijack host cell peroxisomes for replication vacuole expansion and integrity. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr8005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.P.; Li, H.Y.; Li, Z.H.; Cui, Z.Q.; Ma, G.M.; Nassor, A.K.; Guan, Y.; Pan, X.H. Multi-stimuli-responsive pectin-coated dendritic mesoporous silica nanoparticles with Eugenol as a sustained release nanocarrier for the control of tomato bacterial wilt. J. Nanobio 2025, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Niu, Q.; Cui, Y.; Fan, K.; Wang, X. Copper-Doped Prussian Blue Nanozymes: Targeted Starvation Therapy Against Gram-Positive Bacteria via the ABC Transporter Inhibition. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, e07939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.N.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, F.Y.; Zhou, L.P.; Guo, X.C.; Li, Q.Y.; Luo, L.L.; Miao, Y.C.; Huo, Y.N. Initiative invasion promoted photoelectrocatalytic antibacterial function on ZIF-67@CoO@Co foil photoanode. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.Q.; Jiang, W.; Li, J.Y.; Teng, P.; Wei, L.L.; Xu, H.E.; Jiang, X.Q.; Hu, Y. Biomimetic nanodrug breaching tumor cell membrane barrier for high-efficiency drug delivery. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Li, H.; Qi, G.B.; Qian, Y.Y.; Li, B.W.; Shi, L.L.; Liu, B. Combating Fungal Infections and Resistance with a Dual-Mechanism Luminogen to Disrupt Membrane Integrity and Induce DNA Damage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 31656–31664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.Y.; Chen, Y.Q.; Tan, J.C.; Zhou, J.A.; Chen, W.N.; Jiang, T.; Zha, J.Y.; Zeng, X.K.; Li, B.W.; Wei, L.Q.; et al. Global fungal-host interactome mapping identifies host targets of candidalysin. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo-Colorado, B.E.; Arroyo-Salgado, B.; Palacio-Herrera, F.M. Antifungal activity of four Piper genus essential oils against postharvest fungal Fusarium spp. isolated from Mangifera indica L. and Persea americana Mill. fruits. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 223, 120170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkuimi Wandjou, J.G.; Quassinti, L.; Gudžinskas, Z.; Nagy, D.U.; Cianfaglione, K.; Bramucci, M.; Maggi, F.J.C. Chemical composition and antiproliferative effect of essential oils of four Solidago species (S. canadensis, S. gigantea, S. virgaurea and S.× niederederi). Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e2000685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yu, M.; Wei, Y.; Xu, F.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Y.; Ding, P.; Shao, X. Cinnamon essential oil causes cell membrane rupture and oxidative damage of Rhizopus stolonifer to control soft rot of peaches. Food Control 2025, 170, 111039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Flower | Leaf | Stem | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture content (wt%) | 64.64 ± 1.46 a | 62.08 ± 1.30 b | 52.11 ± 1.53 c |

| Dry weight fraction (%) | 19.53 ± 2.99 b | 59.05 ± 6.14 a | 21.43 ± 4.68 b |

| Biomass (kg (DW)/m2) | 0.64 ± 0.16 b | 1.95 ± 0.43 a | 0.72 ± 0.26 b |

| Yields of SLEO (%DW) | 1.00 ± 0.07 a | 0.76 ± 0.04 b | 0.05 ± 0.01 c |

| Density of SLEOs (g/mL) | 0.86 ± 0.00 | 0.86 ± 0.00 | 0.86 ± 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, J.-X.; Lu, Z.-Z.; Chen, S.; Lin, S.-Y.; Yao, X.-H.; Chen, T.; Zhang, D.-Y. Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Solidago canadensis L. Essential Oil and Its Antifungal Mechanism Against Mulberry Sclerotinia Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010049

Yang J-X, Lu Z-Z, Chen S, Lin S-Y, Yao X-H, Chen T, Zhang D-Y. Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Solidago canadensis L. Essential Oil and Its Antifungal Mechanism Against Mulberry Sclerotinia Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010049

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Jia-Xin, Zhen-Zhen Lu, Sen Chen, Shi-Yi Lin, Xiao-Hui Yao, Tao Chen, and Dong-Yang Zhang. 2026. "Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Solidago canadensis L. Essential Oil and Its Antifungal Mechanism Against Mulberry Sclerotinia Diseases" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010049

APA StyleYang, J.-X., Lu, Z.-Z., Chen, S., Lin, S.-Y., Yao, X.-H., Chen, T., & Zhang, D.-Y. (2026). Multivariate Statistical Analysis of Solidago canadensis L. Essential Oil and Its Antifungal Mechanism Against Mulberry Sclerotinia Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010049