Assessment of Nociception and Inflammatory/Tissue Damage Biomarkers in a Post-COVID-19 Animal Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

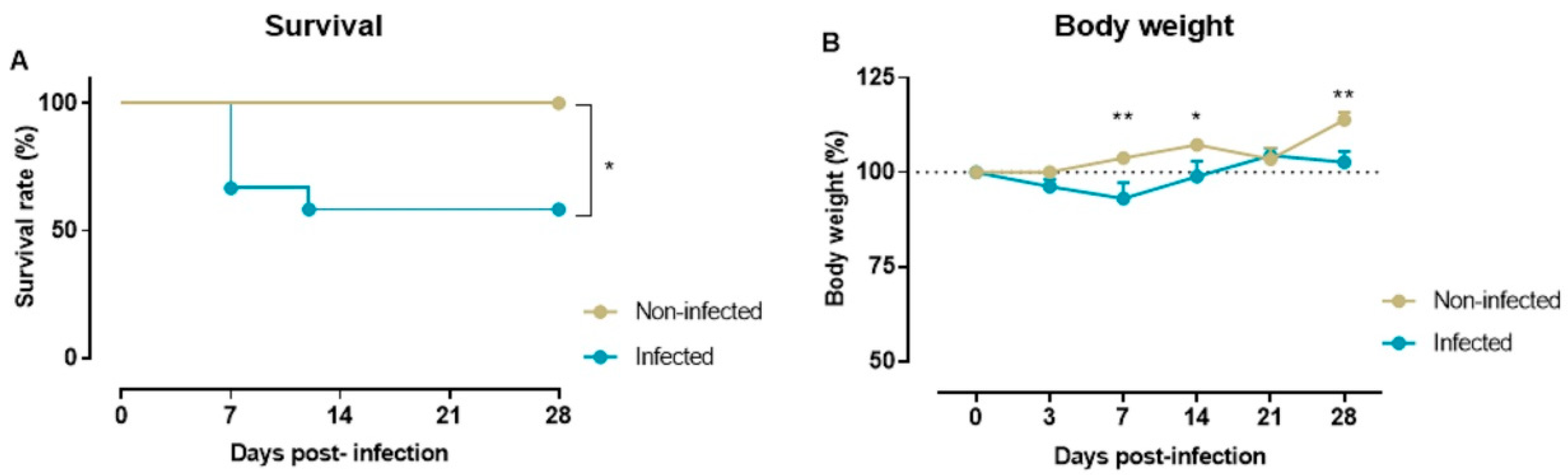

2.1. Survival Rate and Body Weight

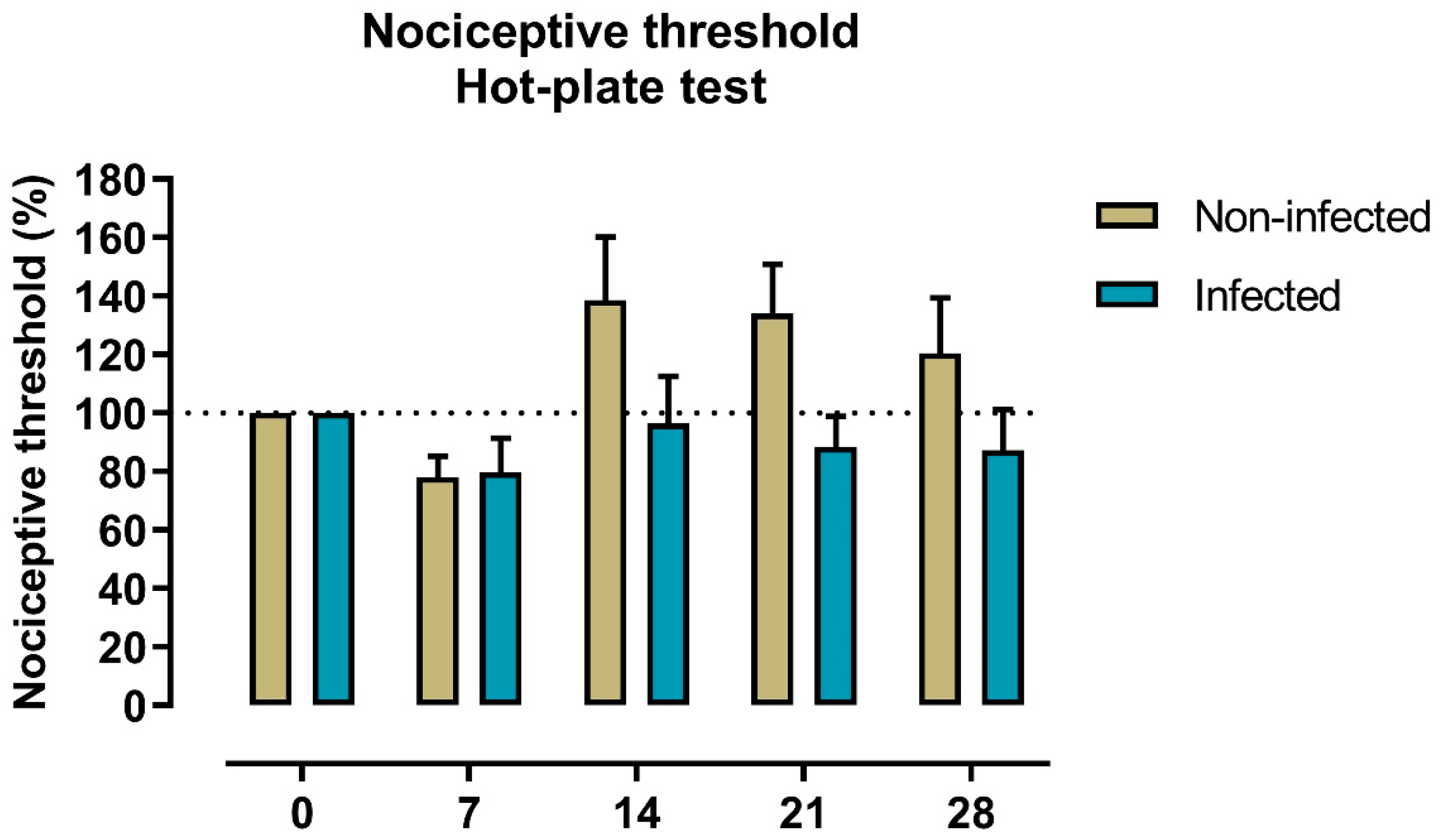

2.2. Nociception to Heat Stimulus

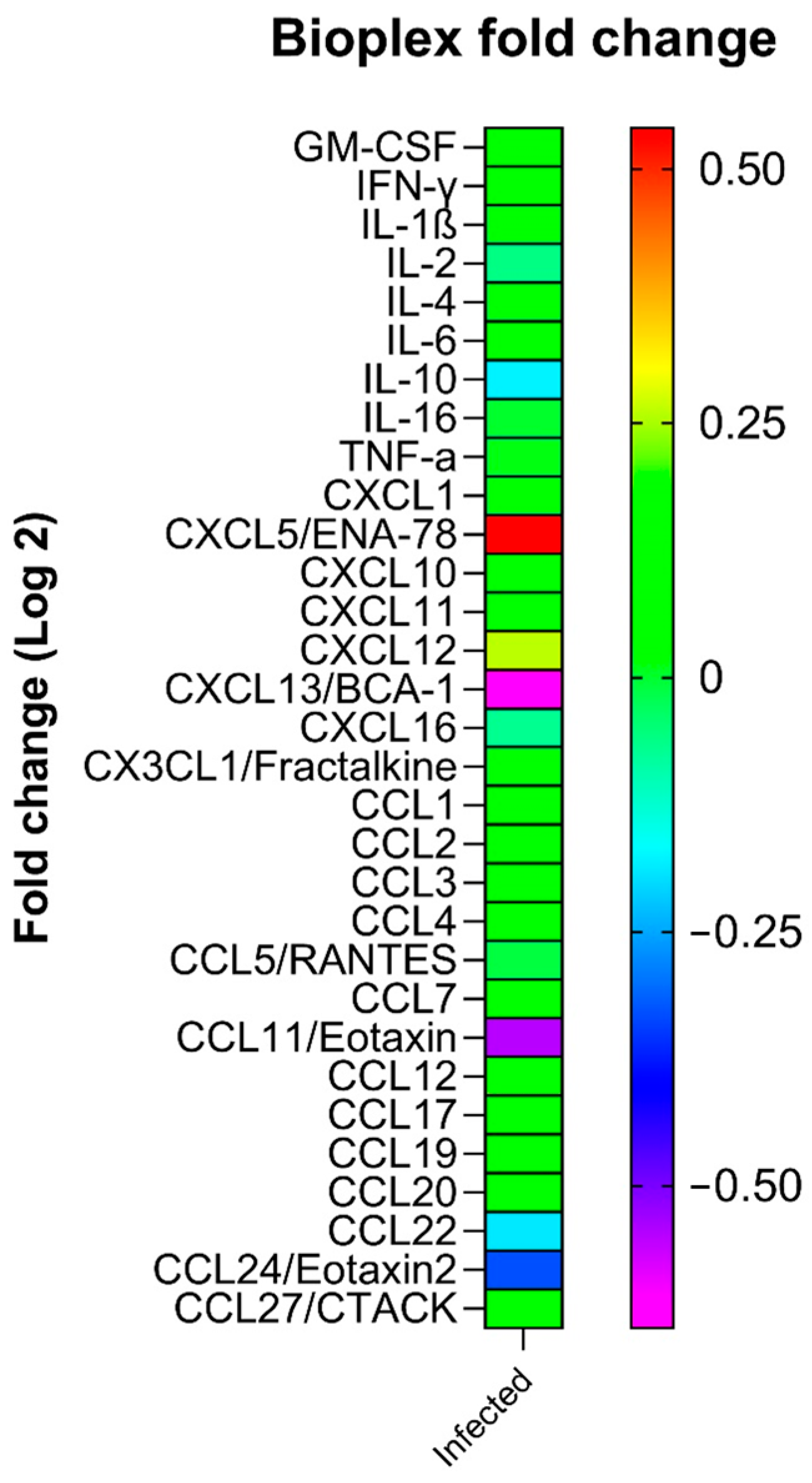

2.3. Plasma Levels of Cytokines

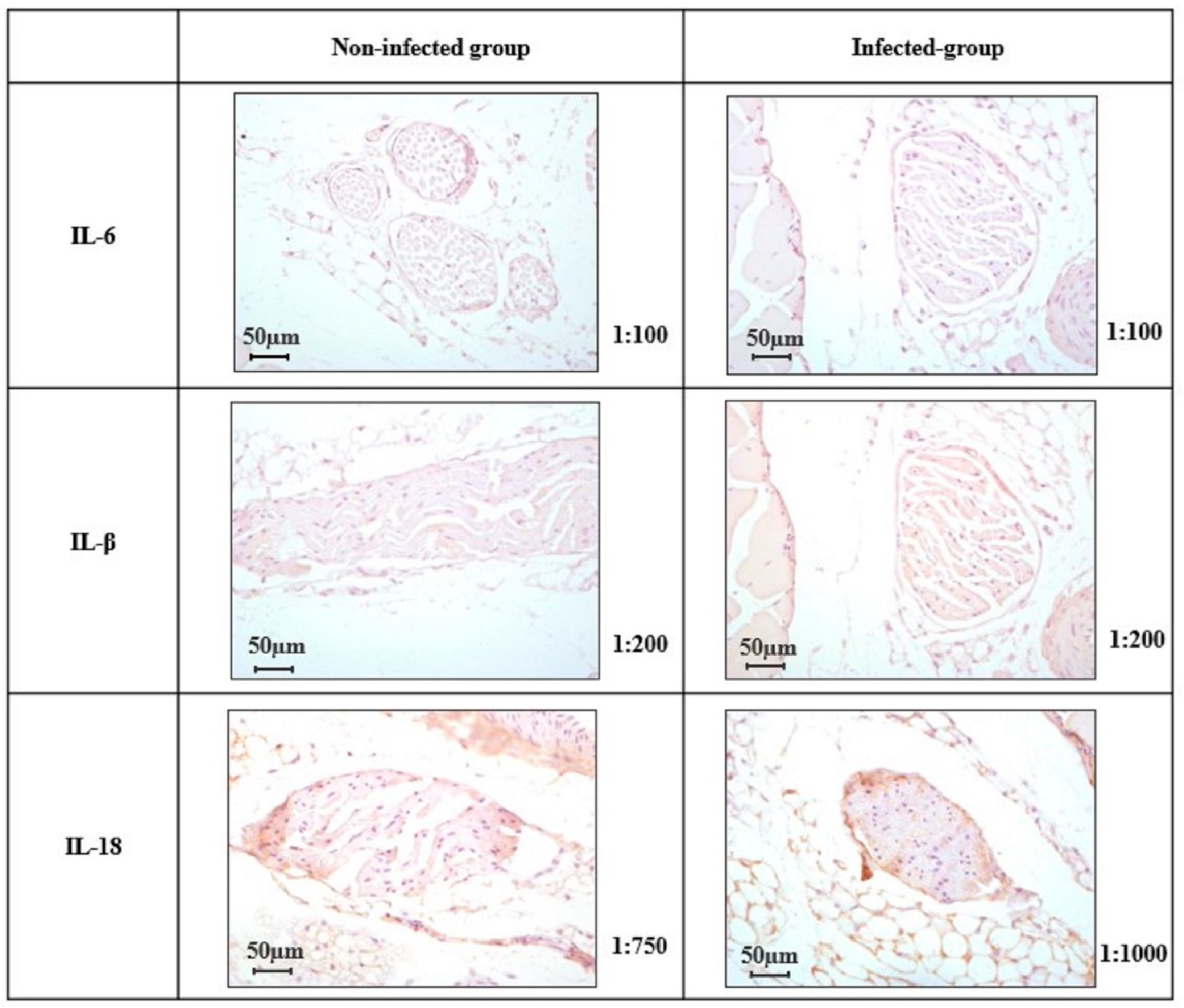

2.4. Expression of IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-18 in the Peripheral Nerve

3. Discussion

3.1. Pain Sensitivity After SARS-CoV-2 Infection

3.2. Long-Lasting Presence of Inflammatory Biomarkers

3.3. Nerve Damage After SARS-CoV-2 Infection

3.4. Strengths and Limitations

4. Methods

4.1. Ethics Statement

4.2. Model of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Female Mice

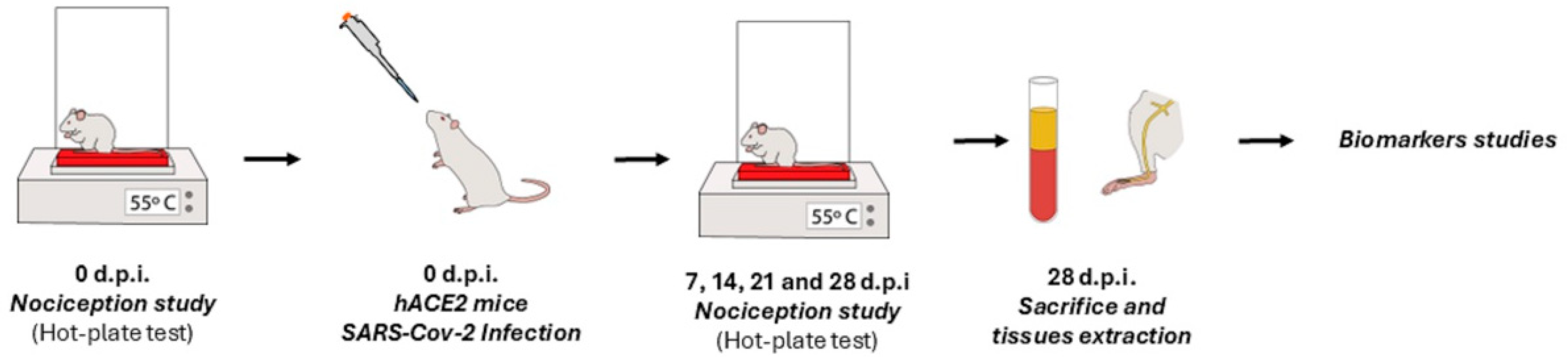

4.3. Experimental Design

4.4. Evaluation of Nociceptive Threshold to Heat Stimulus: Hot-Plate Test

4.5. Plasma Inflammatory Marker Multiplex Analysis

4.6. Immunohistochemical Analysis in Saphenous Nerve

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Cases, World. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2025. Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Fernandez-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Notarte, K.I.; Macasaet, R.; Velasco, J.V.; Catahay, J.A.; Ver, A.T.; Chung, W.; Valera-Calero, J.A.; Navarro-Santana, M. Persistence of Post-COVID Symptoms in the General Population Two Years After SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Infect. 2024, 88, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M.; Udeh, R.; Kang, J.; Dolja-Gore, X.; McEvoy, M.; Kazemi, A.; Soysal, P.; Smith, L.; Kenna, T.; Fond, G.; et al. Long-Term Sequelae of COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Symptoms 3 Years Post-SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J. Med. Virol. 2025, 97, e70429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazian, S.S.; Vemuri, A.; Vafaei Sadr, A.; Shahjouei, S.; Bahrami, S.; Shouhao, Z.; Abedi, V.; Zand, R. The Health-Related Quality of Life among Survivors with Post-COVID Conditions in the United States. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Doran, T.; Crooks, M.G.; Khunti, K.; Heightman, M.; Gonzalez-Izquierdo, A.; Qummer Ul Arfeen, M.; Loveless, A.; Banerjee, A.; Van Der Feltz-Cornelis, C. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Characterisation of Individuals with Long COVID using Electronic Health Records in Over 1.5 Million COVID Cases in England. J. Infect. 2024, 89, 106235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuodi, P.; Gorelik, Y.; Gausi, B.; Bernstine, T.; Edelstein, M. Characterization of Post-COVID Syndromes by Symptom Cluster and Time Period Up to 12 Months Post-Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 134, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiala, K.; Martens, J.; Abd-Elsayed, A. Post-COVID Pain Syndromes. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2022, 26, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Navarro-Santana, M.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Time Course Prevalence of Post-COVID Pain Symptoms of Musculoskeletal Origin in Patients Who had Survived Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain 2022, 163, 1220–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerzhner, O.; Berla, E.; Har-Even, M.; Ratmansky, M.; Goor-Aryeh, I. Consistency of Inconsistency in Long-COVID-19 Pain Symptoms Persistency: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Pract. 2024, 24, 120–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, F.H.C.; Kubota, G.T.; Fernandes, A.M.; Hojo, B.; Couras, C.; Costa, B.V.; Lapa, J.D.d.S.; Braga, L.M.; Almeida, M.M.d.; Cunha, P.H.M.d.; et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of New-Onset Pain in COVID-19 Survivours, a Controlled Study. Eur. J. Pain 2021, 25, 1342–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; de-la-Llave-Rincón, A.I.; Ortega-Santiago, R.; Ambite-Quesada, S.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Cuadrado, M.L.; Arias-Navalón, J.A.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Martín-Guerrero, J.D.; Pellicer-Valero, O.J.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Musculoskeletal Pain Symptoms as Long-Term Post-COVID Sequelae in Hospitalized COVID-19 Survivors: A Multicenter Study. Pain 2022, 163, e989–e996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, G.T.; Soares, F.H.C.; da Fonseca, A.S.; Rosa, T.D.S.; da Silva, V.A.; Gouveia, G.R.; Faria, V.G.; da Cunha, P.H.M.; Brunoni, A.R.; Teixeira, M.J.; et al. Pain Paths among Post-COVID-19 Condition Subjects: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study with in-Person Evaluation. Eur. J. Pain 2023, 27, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbesen, B.D.; Giordano, R.; Hedegaard, J.N.; Calero, J.A.V.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Rasmussen, B.S.; Nielsen, H.; Schiøttz-Christensen, B.; Petersen, P.L.; Castaldo, M.; et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Multitype Post-COVID Pain in a Cohort of Previously Hospitalized COVID-19 Survivors: A Danish Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Pain 2024, 25, 104579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, S.; Liu, M.; Yang, Y.; Kang, N.; Song, Y.; Tan, D.; Liu, N.; Wang, F.; Liu, J.; Xie, Y. Animal Models for COVID-19: Hamsters, Mouse, Ferret, Mink, Tree Shrew, and Non-Human Primates. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 626553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Pierce, J.; Franklin, C.; Olson, R.M.; Morrison, A.R.; Amos-Landgraf, J. Translating Animal Models of SARS-CoV-2 Infection to Vascular, Neurological and Gastrointestinal Manifestations of COVID-19. Dis. Model. Mech. 2025, 18, dmm052086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarnagin, K.; Alvarez, O.; Shresta, S.; Webb, D.R. Animal Models for SARS-Cov2/Covid19 Research-A Commentary. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 188, 114543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez de Oya, N.; Calvo-Pinilla, E.; Mingo-Casas, P.; Escribano-Romero, E.; Blázquez, A.; Esteban, A.; Fernández-González, R.; Pericuesta, E.; Sánchez-Cordón, P.J.; Martín-Acebes, M.A.; et al. Susceptibility and Transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 Variants in Transgenic Mice Expressing the Cat Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE-2) Receptor. One Health 2024, 18, 100744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Torres-Macho, J.; Macasaet, R.; Velasco, J.V.; Ver, A.T.; Culasino Carandang, T.H.D.; Guerrero, J.J.; Franco-Moreno, A.; Chung, W.; Notarte, K.I. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in COVID-19 Survivors with Post-COVID Symptoms: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2024, 62, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Torres-Macho, J.; Ruiz-Ruigómez, M.; Arrieta-Ortubay, E.; Rodríguez-Rebollo, C.; Akasbi-Moltalvo, M.; Pardo-Guimerá, V.; Ryan-Murua, P.; Lumbreras-Bermejo, C.; Pellicer-Valero, O.J.; et al. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in COVID-19 Survivors with Post-COVID Symptoms 2 Years After Hospitalization: The VIPER Study. J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Mei, B.; Wang, P.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Wei, G.; Kuang, F.; Li, B.; Su, S. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Persistent Symptoms After COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderheiden, A.; Diamond, M.S. Animal Models of Non-Respiratory, Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19. Viruses 2025, 17, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Sun, F.; Yu, N.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Z.; Wang, N.; Yuan, B.; Liu, P.; et al. TLR2/NF-κB Signaling in Macrophage/Microglia Mediated COVID-Pain Induced by SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein. iScience 2024, 27, 111027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Parás-Bravo, P.; Ferrer-Pargada, D.; Cancela-Cilleruelo, I.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, J.; Nijs, J.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Herrero-Montes, M. Sensitization Symptoms are Associated with Psychological and Cognitive Variables in COVID-19 Survivors Exhibiting Post-COVID Pain. Pain Pract. 2023, 23, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudman, L.; De Smedt, A.; Roggeman, S.; Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Hatem, S.M.; Schiltz, M.; Billot, M.; Roulaud, M.; Rigoard, P.; Moens, M. Association between Experimental Pain Measurements and the Central Sensitization Inventory in Patients at Least 3 Months After COVID-19 Infection: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, F.d.T.; Firigato, I.; Pessotto, A.V.; Carvalho Soares, F.H.; Martins, F.; Dos Santos Rosa, T.; Kubota, G.T.; de Andrade, D.C.; Faria, V.G.; Fregni, F.; et al. De Novo Post-COVID-19 Chronic Pain: A Piece of Information about Risk Factor and Clinical Features. Pain Rep. 2025, 10, e1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, A.; Fregna, G.; Lamberti, N.; Manfredini, F.; Straudi, S. Fatigue can Influence the Development of Late-Onset Pain in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: An Observational Study. Eur. J. Pain 2024, 28, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P.; Wang, E.J.; Doshi, T.L.; Vase, L.; Cawcutt, K.A.; Tontisirin, N. Chronic Pain and Infection: Mechanisms, Causes, Conditions, Treatments, and Controversies. BMJ Med. 2022, 1, e000108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Liu, S.; Manachevakul, S.; Lee, T.; Kuo, C.; Bello, D. Biomarkers in Long COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1085988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, S.J.; Halim, A.; Halim, M.; Liu, S.; Aljeldah, M.; Al Shammari, B.R.; Alwarthan, S.; Alhajri, M.; Alawfi, A.; Alshengeti, A.; et al. Inflammatory and Vascular Biomarkers in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Over 20 Biomarkers. Rev. Med. Virol. 2023, 33, e2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Agbana, Y.L.; Sun, Z.; Fei, S.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, X.; Chen, J.; Kassegne, K. Increased Interleukin-6 is Associated with Long COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, C.; Liu, B.; Dong, Z.; Shi, S.; Peng, C.; Pan, Y.; Bi, X.; Nie, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tai, Y.; et al. CXCL5 Activates CXCR2 in Nociceptive Sensory Neurons to Drive Joint Pain and Inflammation in Experimental Gouty Arthritis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3263–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, S.; Fang, M.; Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, Q.; Xu, Y.; Mai, C.; Wan, J.; Yu, Y.; Wei, M.; et al. Elevated Plasma CXCL12 Leads to Pain Chronicity Via Positive Feedback Upregulation of CXCL12/CXCR4 Axis in Pain Synapses. J. Headache Pain 2024, 25, 213-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xia, Y.; Liu, B.; Fang, J.; Hu, Q. The CXCL12/CXCR4 Axis: An Emerging Therapeutic Target for Chronic Pain. J. Pain Res. 2025, 18, 2583–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussmann, A.J.C.; Ferraz, C.R.; Lima, A.V.A.; Castro, J.G.S.; Ritter, P.D.; Zaninelli, T.H.; Saraiva-Santos, T.; Verri, W.A.J.; Borghi, S.M. Association between IL-10 Systemic Low Level and Highest Pain Score in Patients during Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Pain Pract. 2022, 22, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, D.; Gyanpuri, V.; Pathak, A.; Chaurasia, R.N.; Mishra, V.N.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.K.; Dhiman, N.R. Neuropathic Pain Associated with COVID-19: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2022, 26, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, J.; Finnerup, N.B.; Attal, N.; Aziz, Q.; Baron, R.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Cruccu, G.; Davis, K.D.; et al. The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for ICD-11: Chronic Neuropathic Pain. Pain 2019, 160, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, G.; Falco, P.; Galosi, E.; Di Pietro, G.; Leone, C.; Truini, A. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Neuropathic Pain Associated with Coronavirus Disease 2019. Eur. J. Pain 2023, 27, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.D.; Zis, P. COVID-19-Related Neuropathic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailhot, B.; Christin, M.; Tessandier, N.; Sotoudeh, C.; Bretheau, F.; Turmel, R.; Pellerin, È.; Wang, F.; Bories, C.; Joly-Beauparlant, C.; et al. Neuronal Interleukin-1 Receptors Mediate Pain in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20191430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goshi, N.; Lam, D.; Bogguri, C.; George, V.K.; Sebastian, A.; Cadena, J.; Leon, N.F.; Hum, N.R.; Weilhammer, D.R.; Fischer, N.O.; et al. Direct Effects of Prolonged TNF-A and IL-6 Exposure on Neural Activity in Human iPSC-Derived Neuron-Astrocyte Co-Cultures. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1512591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudeva, K.; Vodovotz, Y.; Azhar, N.; Barclay, D.; Janjic, J.M.; Pollock, J.A. In Vivo and Systems Biology Studies Implicate IL-18 as a Central Mediator in Chronic Pain. J. Neuroimmunol. 2015, 283, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, L.; Zubair, A.S.; Joseph, P.; Spudich, S. Case-Control Study of Individuals with Small Fiber Neuropathy After COVID-19. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 11, e200244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usai, C.; Mateu, L.; Brander, C.; Vergara-Alert, J.; Segalés, J. Animal Models to Study the Neurological Manifestations of the Post-COVID-19 Condition. Lab. Anim. 2023, 52, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas, C.; Notarte, K.I.; Peligro, P.J.; Velasco, J.V.; Ocampo, M.J.; Henry, B.M.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Torres-Macho, J.; Plaza-Manzano, G. Long-COVID Symptoms in Individuals Infected with Different SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Viruses 2022, 14, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Pulido, M.; Calvo-Pinilla, E.; Polo, M.; Saiz, J.; Fernández-González, R.; Pericuesta, E.; Gutiérrez-Adán, A.; Sobrino, F.; Martín-Acebes, M.A.; Sáiz, M. Non-Coding RNAs Derived from the Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus Genome Trigger Broad Antiviral Activity Against Coronaviruses. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1166725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Sengupta, P. Men and Mice: Relating their Ages. Life Sci. 2016, 152, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.B.; Murthy, S.; Marshall, J.C.; Relan, P.; Diaz, J.V. WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A Clinical Case Definition of Post-COVID-19 Condition by a Delphi Consensus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, e102–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, E.; Paniagua, N.; Sánchez-Robles, E.M.; Girón, R.; Alvarez de la Rosa, D.; Giraldez, T.; Goicoechea, C. SGK1.1 Isoform is Involved in Nociceptive Modulation, Offering a Protective Effect Against Noxious Cold Stimulus in a Sexually Dimorphic Manner. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2022, 212, 173302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, X.; Sun, X.; Cao, Z.; Qiao, J.; Yang, S.; Meng, X.; Zhao, Y. Optimal Ratio of 18α- and 18β-Glycyrrhizic Acid for Preventing Alcoholic Hepatitis in Rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.H.; Krishnan, V.V.; Ziman, M.; Janatpour, K.; Wun, T.; Luciw, P.A.; Tuscano, J. A Comparison of Multiplex Suspension Array Large-Panel Kits for Profiling Cytokines and Chemokines in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Cytom. B Clin. Cytom. 2009, 76, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshourab, R.; Schmidt, Y.; Machelska, H. Skin-Nerve Preparation to Assay the Function of Opioid Receptors in Peripheral Endings of Sensory Neurons. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1230, 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Su, P.P.; He, L.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J.; Guan, Z. Saphenous-Sural Nerve Injury: A Sensory-Specific Rodent Model of Neuropathic Pain without Motor Deficits. Pain 2025, 166, 2563–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Analyte | Infected Group (n = 7) | Non-Infected Group (n = 11) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GM-CSF | 28.16 ± 3.45 | 25.07 ± 3.49 | 0.5591 |

| IFN-γ | 327.0 ± 52.06 | 285.10 ± 26.59 | 0.4405 |

| IL-1β | 213.30 ± 30.86 | 198.80 ± 14.39 | 0.6461 |

| IL-2 | 15.39 ± 2.69 | 14.74 ± 1.52 | 0.8251 |

| IL-4 | 146.6 ± 25.85 | 133.0 ± 12.73 | 0.6067 |

| IL-6 | 120.7 ± 20.96 | 102.50 ± 13.71 | 0.4572 |

| IL-10 | 3369.0 ± 581.40 | 3493.0 ± 270.0 | 0.8293 |

| IL-16 | 600.40 ± 93.89 | 563.90 ± 59.34 | 0.7337 |

| TNF-α | 615.40 ± 92.07 | 572.30 ± 57.43 | 0.6809 |

| CCL1 | 56.86 ± 8.22 | 49.48 ± 5.03 | 0.4270 |

| CCL2 | 1033.0 ± 126.80 | 950.10 ± 77.20 | 0.5622 |

| CCL3 | 92.50 ± 12.03 | 84.82 ± 7.04 | 0.5623 |

| CCL4 | 267.4 ± 20.32 | 251.0 ± 26.25 | 0.6634 |

| CCL5/RANTES | 76.42 ± 10.20 | 73.08 ± 7.79 | 0.7963 |

| CCL7 | 186.60 ± 24.55 | 168.40 ± 13.97 | 0.4964 |

| CCL11/Eotaxin | 140.90 ± 25.55 | 189.0 ± 27.85 | 0.2533 |

| CCL12 | 41.13 ± 3.63 | 35.64 ± 2.63 | 0.2283 |

| CCL17 | 829.40 ± 162.30 | 721.40 ± 79.97 | 0.5159 |

| CCL19 | 3440.0 ± 416.30 | 3064.0 ± 307.30 | 0.4695 |

| CCL20 | 74.19 ± 7.87 | 69.46 ± 4.80 | 0.5931 |

| CCL22 | 451.50 ± 49.53 | 495.30 ± 46.34 | 0.5427 |

| CCL24/Eotaxin2 | 5065.0 ± 433.20 | 6218.0 ± 581.90 | 0.1748 |

| CCL27/CTACK | 2864.0 ± 331.60 | 2543.0 ± 196.40 | 0.3851 |

| CXCL1 | 943.10 ± 86.90 | 910.0 ± 61.07 | 0.7520 |

| CXCL5/ENA-78 | 22,633.0 ± 1639.0 | 15,798.0 ± 2041.0 | 0.0726 |

| CXCL10 | 3490.0 ± 333.6 | 3274.0 ± 261.0 | 0.6165 |

| CXCL11 | 3973.0 ± 405.10 | 3760.0 ± 452.20 | 0.7504 |

| CXCL12 | 1363.0 ± 129.2 | 1321.0 ± 86.33 | 0.7858 |

| CXCL13/BCA-1 | 1383.0 ± 154.0 | 1602.0 ± 161.40 | 0.2944 |

| CXCL16 | 466.0 ± 34.53 | 481.8 ± 48.18 | 0.8163 |

| CX3CL1/Fractalkine | 222.50 ± 23.36 | 211.80 ± 14.10 | 0.6837 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Robles, E.M.; Rodríguez-Rivera, C.; Paniagua Lora, N.; Herradón Pliego, E.; Goicoechea Garcia, C.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; López-Miranda, V. Assessment of Nociception and Inflammatory/Tissue Damage Biomarkers in a Post-COVID-19 Animal Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010359

Sánchez-Robles EM, Rodríguez-Rivera C, Paniagua Lora N, Herradón Pliego E, Goicoechea Garcia C, Arendt-Nielsen L, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, López-Miranda V. Assessment of Nociception and Inflammatory/Tissue Damage Biomarkers in a Post-COVID-19 Animal Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010359

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Robles, Eva M., Carmen Rodríguez-Rivera, Nancy Paniagua Lora, Esperanza Herradón Pliego, Carlos Goicoechea Garcia, Lars Arendt-Nielsen, Cesar Fernández-de-las-Peñas, and Visitación López-Miranda. 2026. "Assessment of Nociception and Inflammatory/Tissue Damage Biomarkers in a Post-COVID-19 Animal Model" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010359

APA StyleSánchez-Robles, E. M., Rodríguez-Rivera, C., Paniagua Lora, N., Herradón Pliego, E., Goicoechea Garcia, C., Arendt-Nielsen, L., Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C., & López-Miranda, V. (2026). Assessment of Nociception and Inflammatory/Tissue Damage Biomarkers in a Post-COVID-19 Animal Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 359. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010359