Culture Growth Phase-Dependent Influence of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth on Oral Mucosa Cells Proliferation in Paracrine Co-Culture with Urethral Epithelium: Implication for Urethral Reconstruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

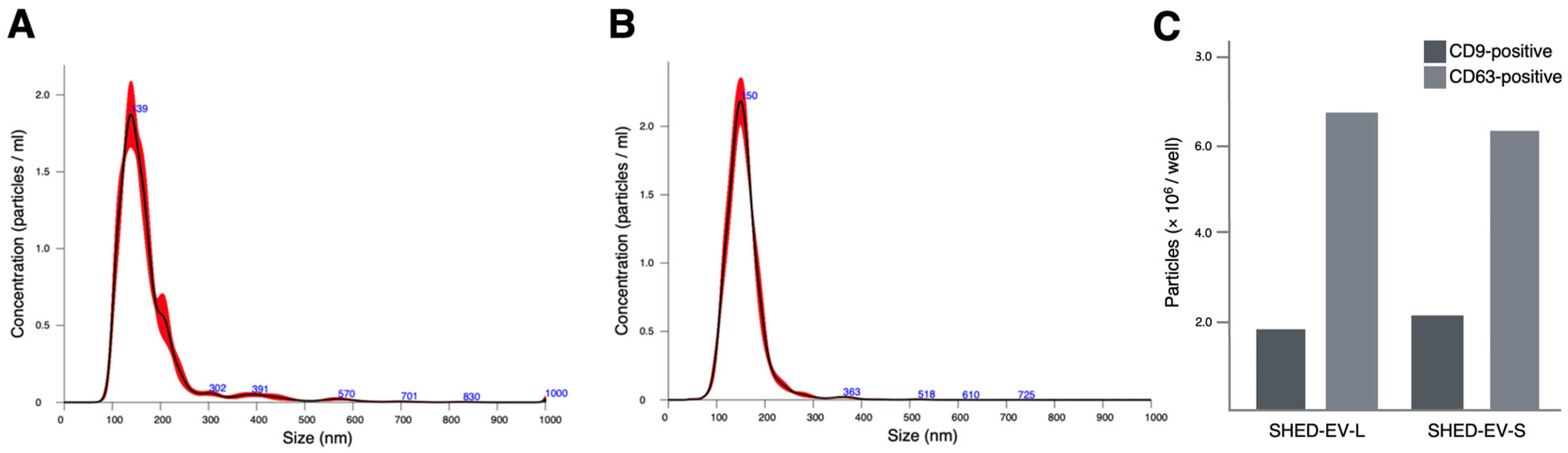

2.1. Characterization of SHED-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

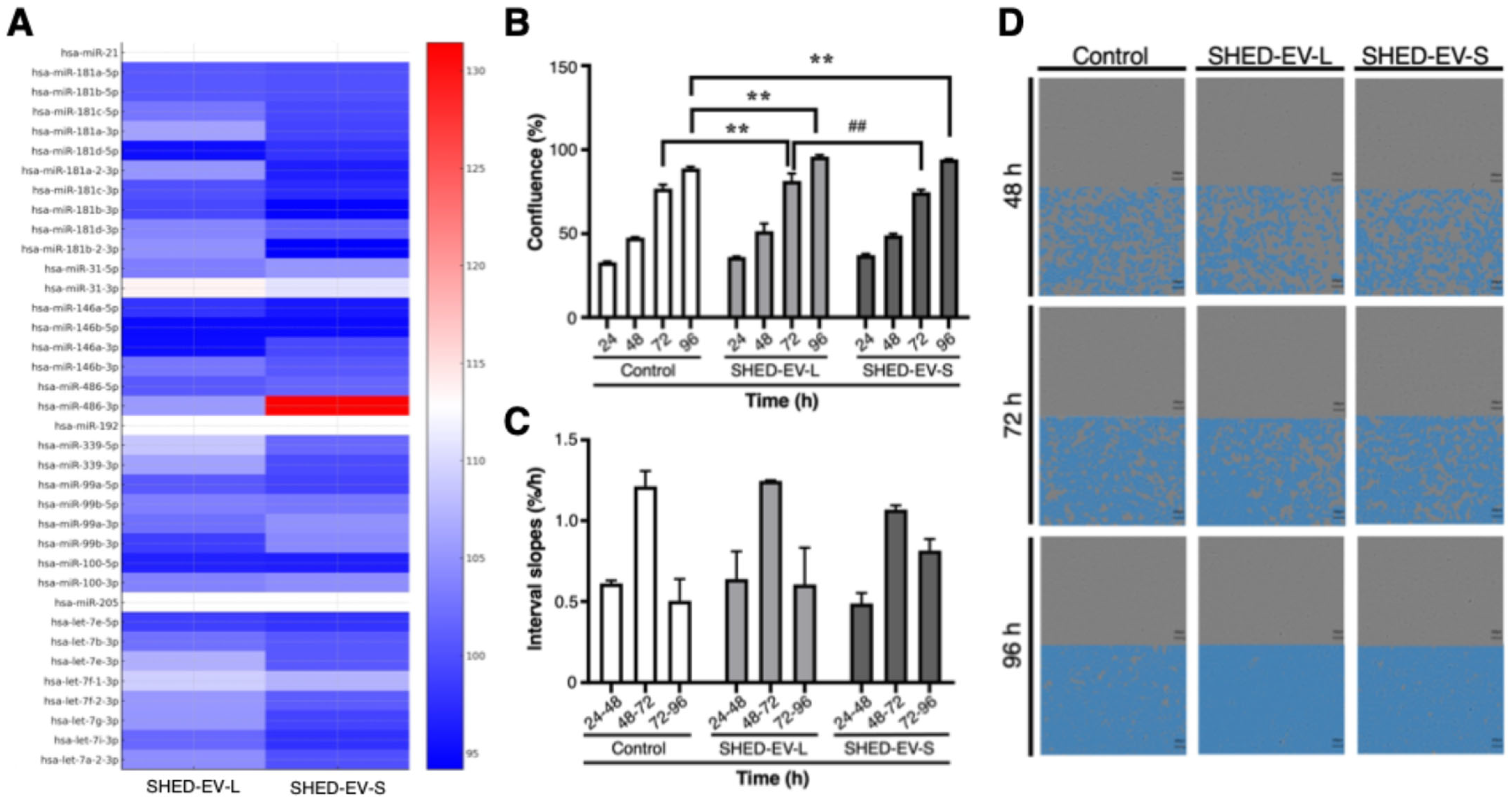

2.2. Fibrosis-Related miRNA Cargo of SHED-EVs in Logarithmic and Stationary Phases

2.3. Proliferative Responses of OMFs to SHED-EVs in Indirect Co-Culture with UECs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Sources and Culture Conditions

4.2. Definition of Growth Phases and Conditioned Medium Collection

4.3. Extracellular Vesicle Isolation and Particle Characterization

4.4. EV Small RNA Extraction and Microarray-Based miRNA Profiling

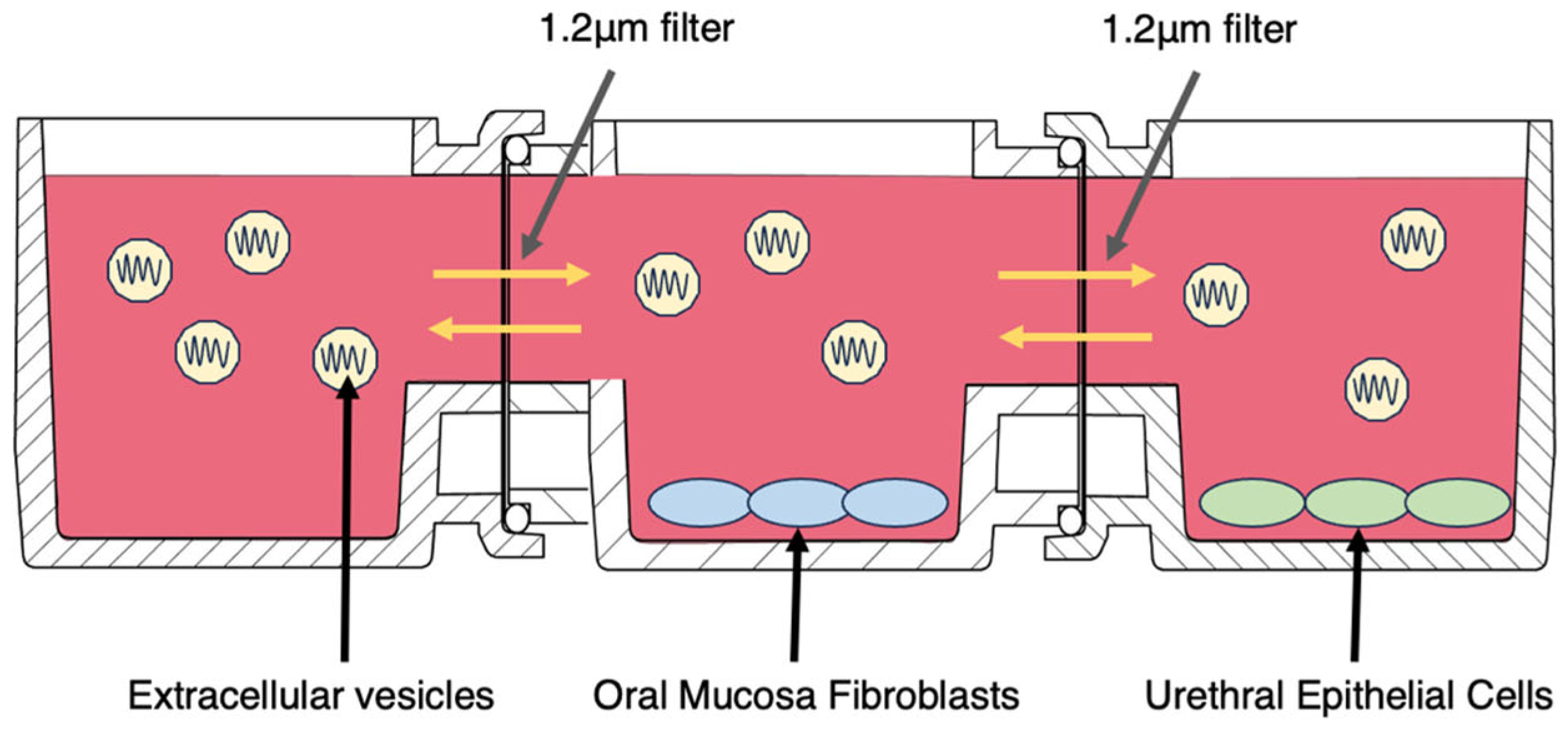

4.5. Cell Proliferation Test (Horizontal Indirect Co-Culture with Real-Time Imaging)

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AOF | Animal-origin-free (medium) |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CM | Conditioned medium |

| DVIU | Direct visual internal urethrotomy |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| EV | Extracellular vesicle |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| HMGA2 | High mobility group AT-hook 2 |

| IGF1R | Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor |

| KGF | Keratinocyte growth factor |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-B |

| NTA | Nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| OMF | Oral mucosa fibroblast |

| OMG | Oral mucosal graft |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| RAS | RAS proto-oncogene family (family of small GTPases) |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| SHED | Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-β |

| UEC | Urethral epithelial cell |

References

- European Association of Urology. EAU Guidelines on Urethral Strictures. Available online: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/urethral-strictures (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Wessells, H.; Morey, A.; Souter, L.; Rahimi, L.; Vanni, A. Urethral Stricture Disease Guideline Amendment (2023). J. Urol. 2023, 210, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, T.L.; Brandes, S.B. Adult Anterior Urethral Strictures: A National Practice Patterns Survey of Board Certified Urologists in the United States. J. Urol. 2007, 177, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbagli, G.; Guazzoni, G.; Lazzeri, M. One-Stage Bulbar Urethroplasty: Retrospective Analysis of the Results in 375 Patients. Eur. Urol. 2008, 53, 828–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolavsky, D.; Manwaring, J.; Bratslavsky, G.; Caza, T.; Landas, S.; Hryniewicz-Jankowska, A.; Kotula, L. Novel Concept and Method of Endoscopic Urethral Stricture Treatment Using Liquid Buccal Mucosal Graft. J. Urol. 2016, 196, 1788–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, K.A.; Li, G.; Manwaring, J.; Nikolavsky, D.A.; Fudym, Y.; Caza, T.; Badar, Z.; Taylor, N.; Bratslavsky, G.; Kotula, L.; et al. Liquid buccal mucosa graft endoscopic urethroplasty: A validation animal study. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 2139–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, D.; Mizushima, A.; Horiguchi, A. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles for Oral Mucosal En-graftment in Urethral Reconstruction: Influence of Tissue Origin and Culture Growth Phase (Log vs. Stationary) on miRNA Content. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, D.B.; McKeown, S.T.; Lundy, F.T.; Irwin, C.R. Phenotypic differences between oral and skin fibroblasts in wound con-traction and growth factor expression. Wound Repair. Regen. 2006, 14, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Feng, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, L.; Hao, L.; Shi, C.; Wang, J.; Li, R.; Ran, X.; Su, Y.; et al. miR-21 regulates skin wound healing by targeting multiple aspects of the healing process. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 181, 1911–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.; Ganesh, K.; Khanna, S.; Sen, C.K.; Roy, S. Engulfment of apoptotic cells by macrophages: A role of microRNA-21 in the resolution of wound inflammation. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhyastha, R.; Madhyastha, H.; Nakajima, Y.; Omura, S.; Maruyama, M. MicroRNA signature in diabetic wound healing: Pro-motive role of miR-21 in fibroblast migration. Int. Wound J. 2012, 9, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, M.C.; Voisey, J.; Zang, T.; Cuttle, L. MicroRNAs involved in human skin burns, wound healing and scarring. Wound Repair. Regen. 2023, 31, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-C.; Nien, C.-J.; Chen, L.-G.; Huang, K.-Y.; Chang, W.-J.; Huang, H.-M. Effects of Sapindus mukorossi Seed Oil on Skin Wound Healing: In Vivo and in Vitro Testing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2579, Erratum in Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20174178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, X.I.; Wang, A.; Meisgen, F.; Pivarcsi, A.; Sonkoly, E.; Ståhle, M.; Landén, N.X. MicroRNA-31 Promotes Skin Wound Healing by Enhancing Keratinocyte Proliferation and Migration. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 1676–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Ma, X.; Su, Y.; Song, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, X.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Shuai, J.; et al. MiR-31 Mediates Inflammatory Signaling to Promote Re-Epithelialization during Skin Wound Healing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 2253–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, I.C.; Meng, S.; Xu, J. miR-146a Decreases Inflammation and ROS Production in Aged Dermal Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y. MiR-486-5p inhibits the hyperproliferation and production of collagen in hypertrophic scar fibroblasts via IGF1/PI3K/AKT pathway. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2021, 32, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Herman-Edelstein, M.; Koh, P.; Burns, W.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Watson, A.; Saleem, M.; Goodall, G.J.; Twigg, S.M.; Cooper, M.E.; et al. E-cadherin expression is regulated by miR-192/215 by a mechanism that is independent of the profibrotic effects of transforming growth factor-beta. Diabetes 2010, 59, 1794–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Chen, Y.; Yang, N.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Geng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.; Dong, C.; Lin, L.; et al. Apoptotic Bodies Derived from Fibroblast-Like Cells in Subcutaneous Connective Tissue Inhibit Ferroptosis in Ischaemic Flaps via the miR-339-5p/KEAP1/Nrf2 Axis. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2307238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Arbieva, Z.H.; Guo, S.; Marucha, P.T.; Mustoe, T.A.; DiPietro, L.A. Positional differences in the wound transcriptome of skin and oral mucosa. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iglesias-Bartolome, R.; Uchiyama, A.; Molinolo, A.A.; Abusleme, L.; Brooks, S.R.; Callejas-Valera, J.L.; Edwards, D.; Doci, C.; Asselin-Labat, M.L.; Onaitis, M.W.; et al. Transcriptional signature primes human oral mucosa for rapid wound healing. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaap8798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, A.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, S.; Marucha, P.T.; Dai, Y.; DiPietro, L.A.; Zhou, X. Differential microRNA profile underlies the divergent healing responses in skin and oral mucosal wounds. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhao, N.; Long, S.; Ge, L.; Wang, A.; Sun, H.; Ran, X.; Zou, Z.; Wang, J.; Su, Y. Downregulation of miR-205 in migrating epithelial tongue facilitates skin wound re-epithelialization by derepressing ITGA5. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssing, I.; Slack, F.J.; Grosshans, H. let-7 microRNAs in development, stem cells and cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roush, S.; Slack, F.J. The let-7 family of microRNAs. Trends Cell Biol. 2008, 18, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyerinas, B.; Park, S.M.; Hau, A.; Murmann, A.E.; Peter, M.E. The role of let-7 in cell differentiation and cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2010, 17, F19–F36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, M.; Zhang, H.; Sone, H.; Itonaga, M. Multiplex quantification of exosomes via multiple types of nanobeads labeling combined with laser scanning detection. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 15577–15584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimasaki, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Omura, R.; Ito, K.; Nishide, Y.; Yamada, H.; Ohtomo, K.; Ishisaka, T.; Okano, K.; Ogawa, T.; et al. Novel Platform for Regulation of Extracellular Vesicles and Metabolites Secretion from Cells Using a Multi-Linkable Horizontal Co-Culture Plate. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | SHED-EV-L (nm, Mean ± SEM) | SHED-EV-S (nm, Mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 175.0 ± 1.4 | 157.1 ± 0.9 |

| Mode | 135.9 ± 6.2 | 150.5 ± 2.9 |

| SD | 87.4 ± 2.5 | 43.0 ± 0.8 |

| D10 | 114.0 ± 1.8 | 116.1 ± 1.0 |

| D50 (Median) | 152.6 ± 1.8 | 151.4 ± 1.0 |

| D90 | 237.8 ± 4.4 | 197.3 ± 1.9 |

| Particle concentration (particles/mL) | 1.64 × 109 ± 0.06 × 109 | 1.54 × 109 ± 0.06 × 109 |

| miRNA | Primary Function | Key Target/Pathways | Implications for Mucosal Grafting | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | Anti-apoptotic, pro-survival, anti-inflammatory | PTEN/AKT, TGF-β | Facilitates early tissue adaptation and helps suppress fibrotic responses | [9,10,11] |

| miR-181 | Anti-inflammatory/anti-fibrotic tuning; restrains EMT | NF-κB axis (via IKK signaling), TGF-β/SMAD signaling | May temper early fibro-inflammation and myofibroblast conversion, supporting stable re-epithelialization and reducing scar formation | [12] |

| miR-31 | Promotes proliferation and migration | RhoA, FZD3, Wnt/β-catenin | Accelerates initial epithelial closure and graft integration | [13,14,15] |

| miR-146 | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, immune-suppressive | TRAF6, IRAK1 | Resolves chronic inflammation, reduces oxidative stress, and facilitates transition from inflammatory to proliferative phase during wound healing | [16] |

| miR-486 | Anti-fibrotic; pro-re-epithelialization | IGF1–PI3K/AKT, SMAD2/3; AKT3 in keratinocyte migration | Could enhance epithelial coverage while limiting collagen I/III deposition and hypertrophic scar-like remodeling | [17] |

| miR-192 | Context-dependent regulator of fibrosis | TGF-β/SMAD network; ECM gene programs | Signal is cell-/context-specific in epithelial tissues; when present, may require phase- or dose-aware use to avoid pro-fibrotic drift | [18] |

| miR-339 | Epithelial phenotype maintenance; EMT restraint; differentiation control | BCL6 (EMT-linked), Wnt/β-catenin pathway components | May help stabilize epithelial identity and curb EMT-driven contraction during graft take; evidence is indirect and hypothesis-generating | [19] |

| miR-99 family (miR-99a/miR-100) | Regulates proliferation and metabolism | mTOR/IGF1R pathway | Maintains controlled epithelial proliferation and energy balance during early repair | [20,21,22] |

| miR-205 | Maintains epithelial phenotype, inhibits EMT | ZEB1/2, E-cadherin | Promotes epithelial integrity; downregulation is required for keratinocyte migration during re-epithelialization; potential therapeutic target in chronic wounds | [23] |

| let-7 family | Controls cell cycle and differentiation; tumor suppression | RAS, HMGA2 | Promotes epithelial stability and suppresses oncogenic transformation in vitro and in vivo | [24,25,26] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kawaharada, T.; Watanabe, D.; Yanagida, K.; Goto, K.; Hu, A.; Segawa, Y.; Higuchi, M.; Shinchi, M.; Horiguchi, A.; Takagi, T.; et al. Culture Growth Phase-Dependent Influence of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth on Oral Mucosa Cells Proliferation in Paracrine Co-Culture with Urethral Epithelium: Implication for Urethral Reconstruction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010314

Kawaharada T, Watanabe D, Yanagida K, Goto K, Hu A, Segawa Y, Higuchi M, Shinchi M, Horiguchi A, Takagi T, et al. Culture Growth Phase-Dependent Influence of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth on Oral Mucosa Cells Proliferation in Paracrine Co-Culture with Urethral Epithelium: Implication for Urethral Reconstruction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010314

Chicago/Turabian StyleKawaharada, Tsuyoshi, Daisuke Watanabe, Kazuki Yanagida, Kashia Goto, Ailing Hu, Yuhei Segawa, Madoka Higuchi, Masayuki Shinchi, Akio Horiguchi, Tatsuya Takagi, and et al. 2026. "Culture Growth Phase-Dependent Influence of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth on Oral Mucosa Cells Proliferation in Paracrine Co-Culture with Urethral Epithelium: Implication for Urethral Reconstruction" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010314

APA StyleKawaharada, T., Watanabe, D., Yanagida, K., Goto, K., Hu, A., Segawa, Y., Higuchi, M., Shinchi, M., Horiguchi, A., Takagi, T., & Mizushima, A. (2026). Culture Growth Phase-Dependent Influence of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth on Oral Mucosa Cells Proliferation in Paracrine Co-Culture with Urethral Epithelium: Implication for Urethral Reconstruction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 314. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010314