Serotonin Application Decreases Fluoxetine-Induced Stress in Lemna minor and Spirodela polyrhiza

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

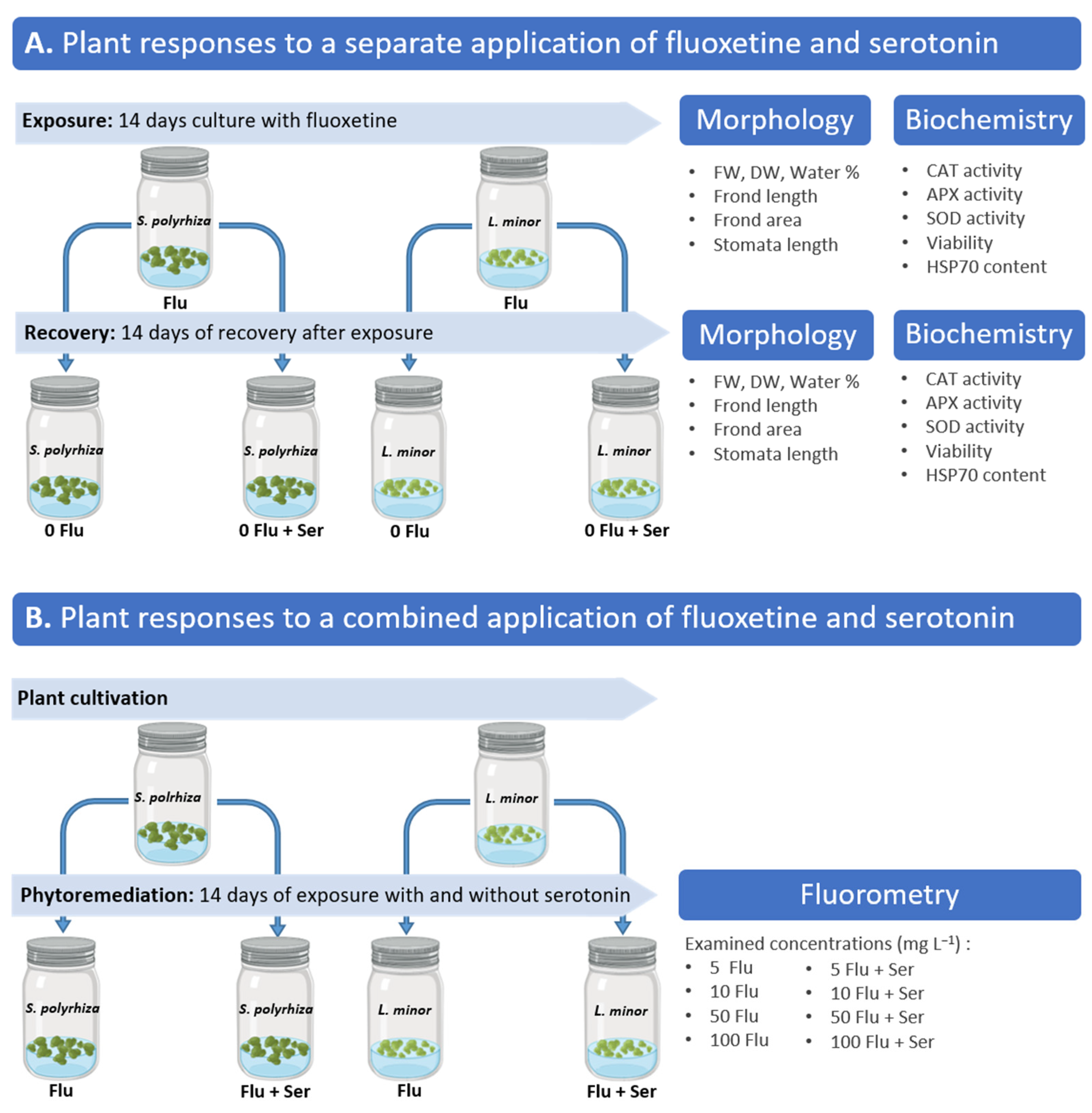

2.1. Plant Responses to Fluoxetine and Serotonin Applied Separately

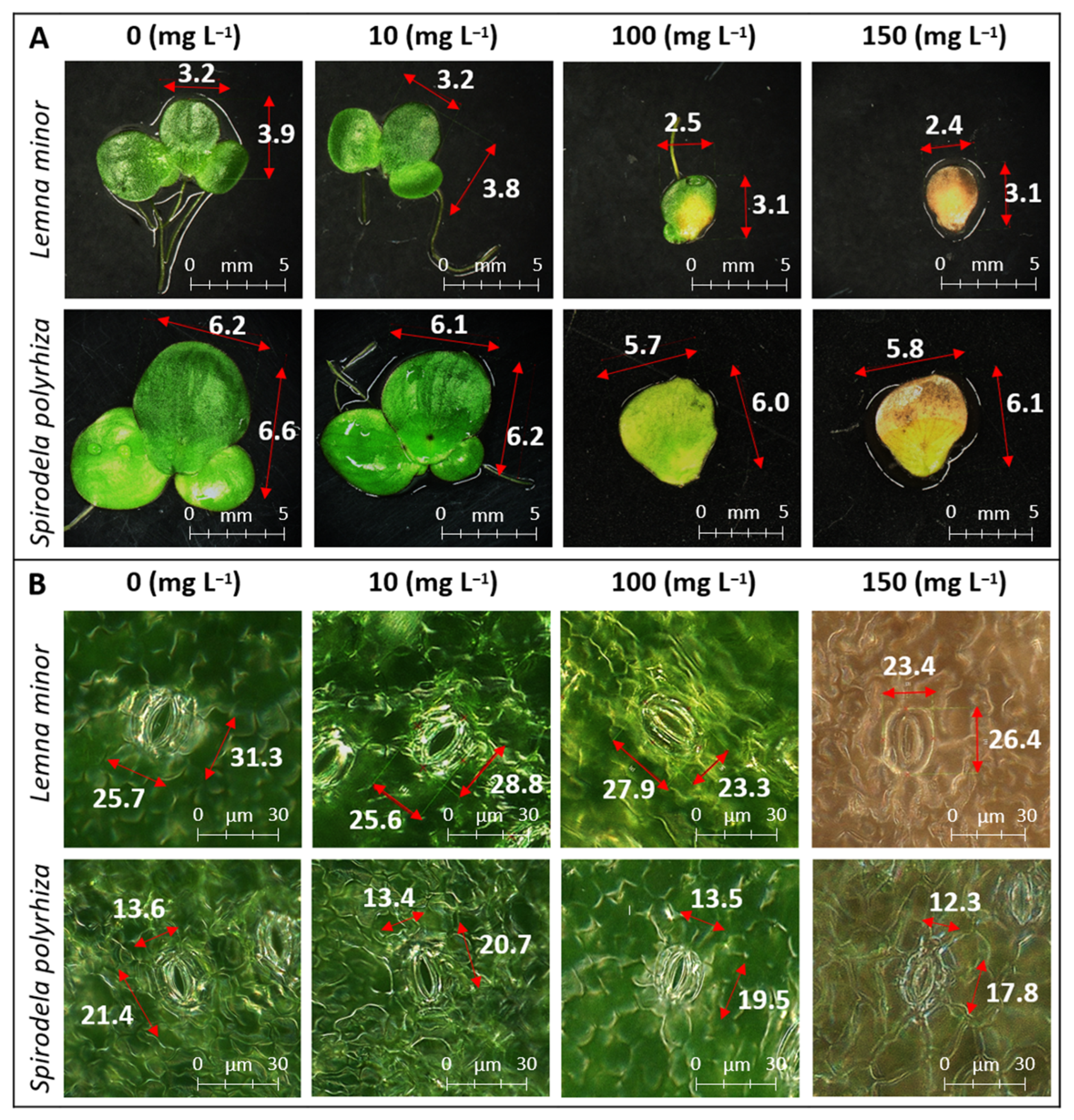

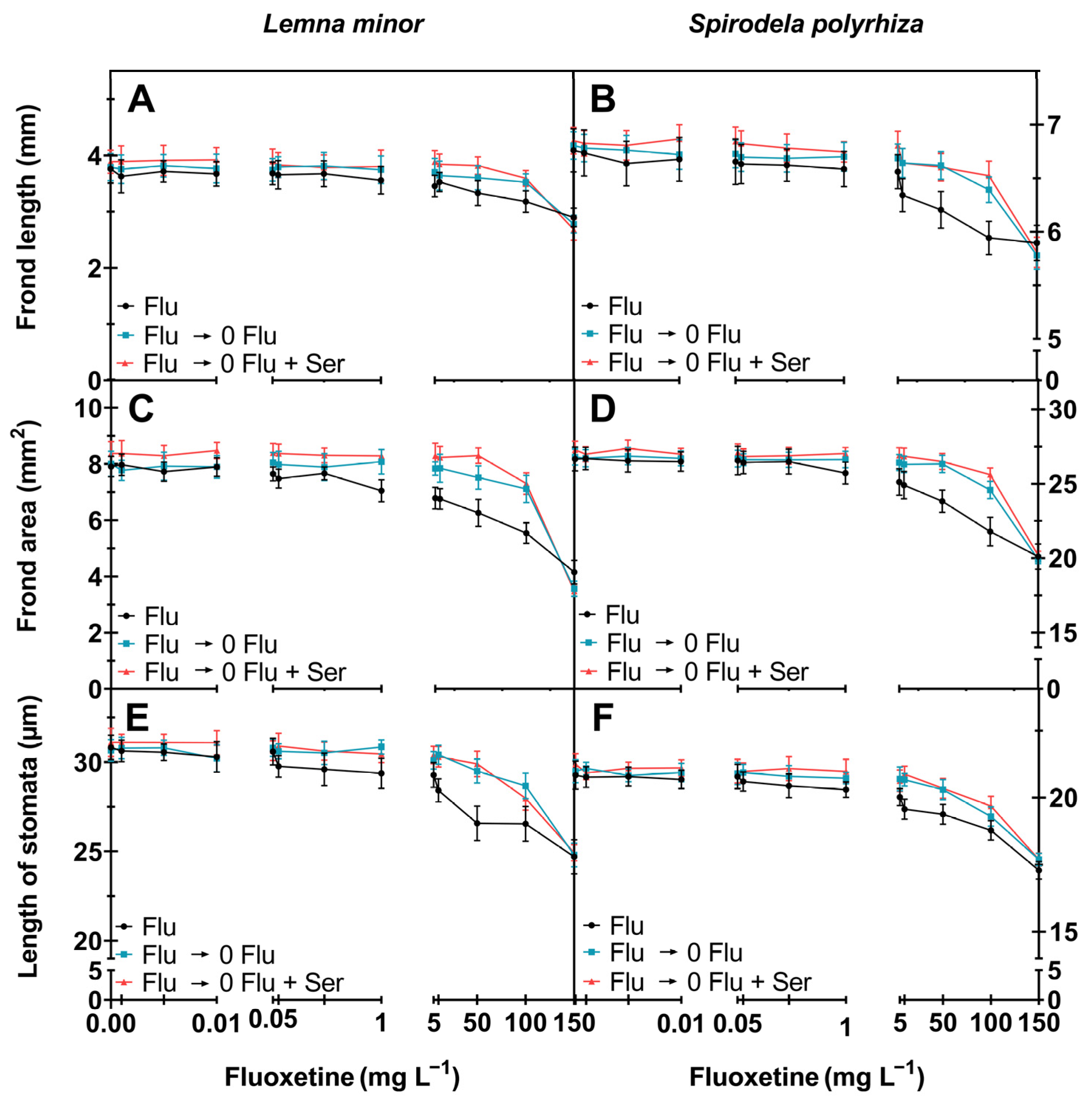

2.1.1. Morphological Parameters

2.1.2. Enzyme Activity

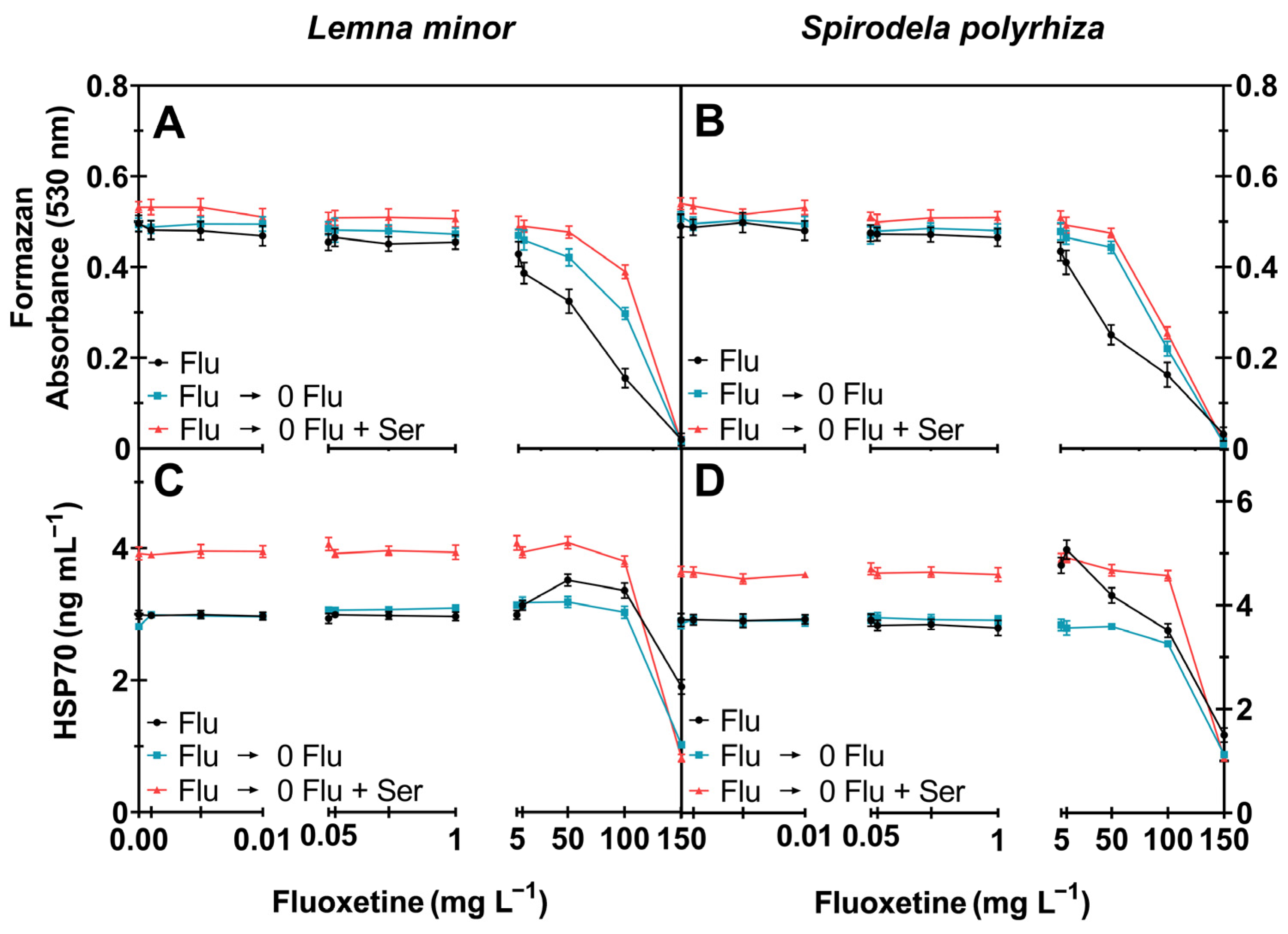

2.1.3. Cell Viability and Stress Response (HSP70)

2.2. Plant Responses to a Combined Application of Fluoxetine and Serotonin

2.2.1. Fluorometric Determination of Fluoxetine Removal from the Medium by Plants

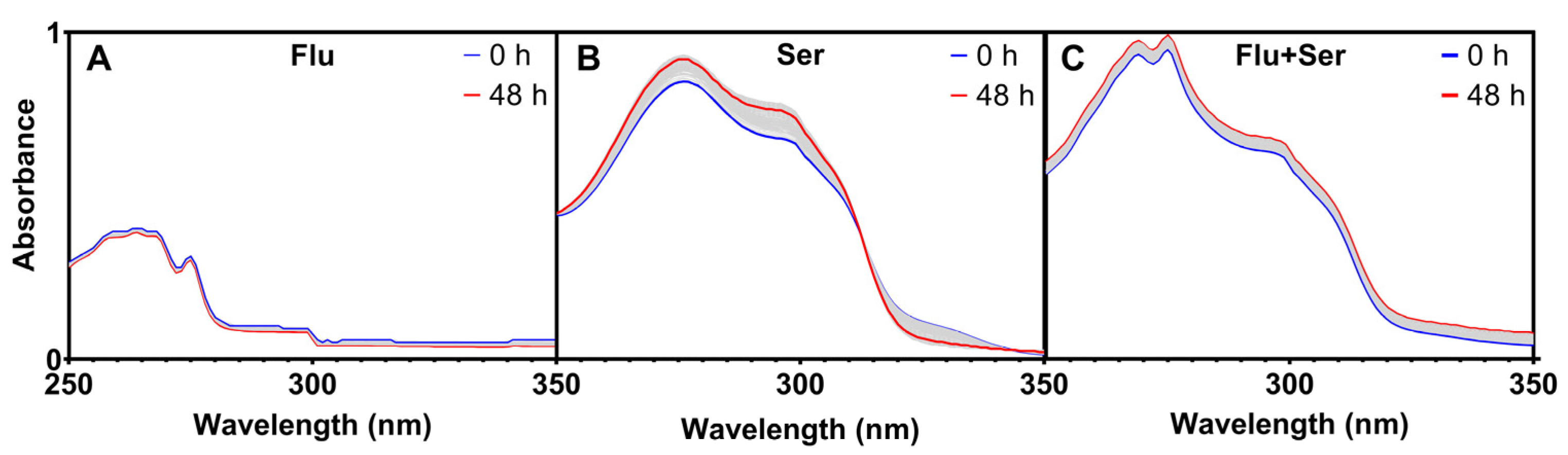

2.2.2. Stability of Fluoxetine and Serotonin in Solutions with No Plants

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

3.2. Morphological Analyses

3.3. Enzymatic Activity Measurements

3.4. Cell Viability and Stress Markers

3.5. Fluorometric Determination of Fluoxetine in the Medium

3.6. Spectrophotometric Measurements

3.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ser | serotonin |

| Flu | fluoxetine |

| CAT | catalase |

| APX | peroxidase |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| SSRI | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| TTC | 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride |

| HSP70 | heat-shock proteins |

| BF | bioconcentration factor |

| RFI | relative fluorescence intensity |

| MS | Murashige and Skoog medium |

| PPCPs | pharmaceuticals and personal care products |

| EDCs | endocrine-disrupting chemicals |

References

- Appenroth, K.J.; Sree, K.S.; Böhm, V.; Hammann, S.; Vetter, W.; Leiterer, M.; Jahreis, G. Nutritional value of duckweeds (Lemnaceae) as human food. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pęczuła, W. Links between two duckweed species (Lemna minor L. and Spirodela polyrhiza (L.) Schleid.), light intensity, and organic matter removal from the water—An experimental study. Water 2025, 17, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Stepanenko, A.; Kishchenko, O.; Xu, J.; Borisjuk, N. Duckweeds for phytoremediation of polluted water. Plants 2023, 12, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.; Petrie, B.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Wolfaardt, G.M. The fate of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), endocrine disrupting contaminants (EDCs), metabolites and illicit drugs in a WWTW and environmental waters. Chemosphere 2017, 174, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, R.; Alfageh, B.; Blais, J.E.; Chan, E.W.; Chui, C.S.L.; Hayes, J.F.; Man, K.K.C.; Lau, W.C.Y.; Yan, V.K.C.; Beykloo, M.Y.; et al. Psychotropic medicine consumption in 65 countries and regions, 2008–2019: A longitudinal study. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety; Ipsos European Public Affairs. Mental Health: Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2875/48999 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Robinson, E.; Sutin, A.R.; Daly, M.; Jones, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 296, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.M.; Markussen, B.; Baun, A.; Halling-Sørensen, B. Probabilistic environmental risk characterization of pharmaceuticals in sewage treatment plant discharges. Chemosphere 2009, 77, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolpin, D.W.; Furlong, E.T.; Meyer, M.T.; Thurman, E.M.; Zaugg, S.D.; Barber, L.B.; Buxton, H.T. Pharmaceuticals, hormones, and other organic wastewater contaminants in streams, 1999–2000: A national reconnaissance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, S.F. A data based perspective on the environmental risk assessment of human pharmaceuticals II—aquatic risk characterisation. In Pharmaceuticals in the Environment, 1st ed.; Kümmerer, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.J.; Lino, C.M.; Meisel, L.M.; Pena, A. Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the aquatic environment: An ecopharmacovigilance approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 437, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowden, K.; Brown, B.G.; Batty, J.E. 5-Hydroxytryptamine: Its occurrence in cowhage. Nature 1954, 174, 925–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshchina, V.V. Neurotransmitters in Plant Life, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001; pp. 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erland, L.A.; Turi, C.E.; Saxena, P.K. Serotonin: An ancient molecule and an important regulator of plant processes. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 1347–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, J.M.; Lee, E.M. Serotonin content of foods: Effect on urinary excretion of 5-hydroxy indoleacetic acid. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 42, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, G.; Lee, H.; Ko, J.; Choi, H.K. Exogenous melatonin enhances the growth and production of bioactive metabolites in Lemna aequinoctialis culture by modulating metabolic and lipidomic profiles. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupka, M.; Michalczyk, D.J.; Žaltauskaitė, J.; Sujetovienė, G.; Głowacka, K.; Grajek, H.; Wierzbicka, M.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.I. Physiological and biochemical parameters of common duckweed Lemna minor after the exposure to tetracycline and the recovery from this stress. Molecules 2021, 26, 6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Morales, D.; Fajardo-Romero, D.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, C.E.; Cedergreen, N. Single and mixture toxicity of selected pharmaceuticals to the aquatic macrophyte Lemna minor. Ecotoxicology 2022, 31, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drobniewska, A.; Giebułtowicz, J.; Wawryniuk, M.; Kierczak, P.; Nałęcz-Jawecki, G. Toxicity and bioaccumulation of selected antidepressants in Lemna minor (L.). Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2024, 24, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, M.; Neale, P.A.; Nidumolu, B.; Kumar, A. Combined toxicity of therapeutic pharmaceuticals to duckweed, Lemna minor. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brain, R.A.; Johnson, D.J.; Richards, S.M.; Sanderson, H.; Sibley, P.K.; Solomon, K.R. Effects of 25 pharmaceutical compounds to Lemna gibba using a seven-day static-renewal test. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2004, 23, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pleiter, M.; Gonzalo, S.; Rodea-Palomares, I.; Leganés, F.; Rosal, R.; Boltes, K.; Marco, E.; Fernandez-Pinas, F. Toxicity of five antibiotics and their mixtures towards photosynthetic aquatic organisms: Implications for environmental risk assessment. Water Res. 2013, 47, 2050–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Santos, L.H.M.L.M.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Figueiredo, S.A. Impact of excipients in the chronic toxicity of fluoxetine on the alga Chlorella vulgaris. Environ. Technol. 2014, 35, 3124–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yang, G. Signal function studies of ROS, especially RBOH-dependent ROS, in plant growth, development and environmental stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, M.; Sarkar, M.; Khan, A.; Biswas, M.; Masi, A.; Rakwal, R.; Agrawal, G.K.; Srivastava, A.; Sarkar, A. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS) in Plants–maintenance of structural individuality and functional blend. Adv. Redox Res. 2022, 5, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbert, Z.; Barroso, J.B.; Brouquisse, R.; Corpas, F.J.; Gupta, K.J.; Lindermayr, C.; Loake, G.J.; Palma, J.M.; Petřivalský, M.; Wendehenne, D.; et al. A forty year journey: The generation and roles of NO in plants. Nitric Oxide 2019, 93, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkan, I. ROS and RNS: Key signalling molecules in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3313–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, J.T.; Veal, D. Nitric oxide, other reactive signalling compounds, redox, and reductive stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C. Active oxygen species and antioxidants in seed biology. Seed Sci. Res. 2004, 14, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: Metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofo, A.; Scopa, A.; Nuzzaci, M.; Vitti, A. Ascorbate peroxidase and catalase activities and their genetic regulation in plants subjected to drought and salinity stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 13561–13578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razinger, J.; Dermastia, M.; Koce, J.D.; Zrimec, A. Oxidative stress in duckweed (Lemna minor L.) caused by short-term cadmium exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2008, 153, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Kumar, D.; Soni, V. Copper and mercury induced oxidative stresses and antioxidant responses of Spirodela polyrhiza (L.) Schleid. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2020, 23, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Feng, K.; Duan, A.Q.; Li, H.; Yang, Q.Q.; Xu, Z.S.; Xiong, A.S. Isolation, purification and characterization of an ascorbate peroxidase from celery and overexpression of the AgAPX1 gene enhanced ascorbate content and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijão, E.; Cruz de Carvalho, R.; Duarte, I.A.; Matos, A.R.; Cabrita, M.T.; Utkin, A.B.; Caçador, I.; Marques, J.C.; Novais, S.C.; Lemos, M.F.L.; et al. Fluoxetine induces photochemistry-derived oxidative stress on Ulva lactuca. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 963537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão-Rocha, F.M.; Rocha, C.H.L.; Martins, M.P.; Sanches, P.R.; Bitencourt, T.A.; Sachs, M.S.; Martinez-Rossi, N.M.; Rossi, A. The antidepressant sertraline affects cell signaling and metabolism in Trichophyton rubrum. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, A.; Giridhar, P.; Ravishankar, G.A. Phytoserotonin: A review. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, X.; Lv, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Li, C.; Yan, L.; Tian, S.; Zou, X. Exogenous serotonin improves salt tolerance in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) seedlings. Agronomy 2021, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavyar, P.H.H.; Amiri, H.; Arnao, M.B.; Bahramikia, S. Exogenous application of serotonin, with the modulation of redox homeostasis and photosynthetic characteristics, enhances the drought resistance of the saffron plant. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drobniewska, A.; Wójcik, D.; Kapłan, M.; Adomas, B.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.; Nałęcz-Jawecki, G. Recovery of Lemna minor after exposure to sulfadimethoxine irradiated and non-irradiated in a solar simulator. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 27642–27652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steponkus, P.L.; Lanphear, F.O. Refinement of the triphenyl tetrazolium chloride method of determining cold injury. Plant Physiol. 1967, 42, 1423–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, A.; Chakrabarti, M.; Ghosh, I.; Mukherjee, A. Evaluation of genotoxicity and oxidative stress of aluminium oxide nanoparticles and its bulk form in Allium cepa. Nucleus 2016, 59, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Zhai, Y.F.; Lu, J.P.; Chai, L.; Chai, W.G.; Gong, Z.H.; Lu, M.H. Characterization of CaHsp70-1, a Pepper Heat-Shock Protein Gene in Response to Heat Stress and Some Regulation Exogenous Substances in Capsicum annuum L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 19741–19759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.G.; Rafii, M.Y.; Martini, M.Y.; Yusuff, O.A.; Ismail, M.R.; Miah, G. Molecular analysis of Hsp70 mechanisms in plants and their function in response to stress. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2017, 33, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorovits, R.; Sobol, I.; Akama, K.; Chefetz, B.; Czosnek, H. Pharmaceuticals in treated wastewater induce a stress response in tomato plants. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziółkowska, A.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.I. Sparfloxacin-a potential contaminant of organically grown plants? Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2016, 14, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmi, B.; Ghasemi-Fasaei, R.; Ronaghi, A.; Mostowfizadeh-Ghalamfarsa, R. Investigation of factors affecting phytoremediation of multi-elements polluted calcareous soil using Taguchi optimization. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 207, 111315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichl, B.; Himmelsbach, M.; Emhofer, L.; Klampfl, C.W.; Buchberger, W. Uptake and metabolism of the antidepressants sertraline, clomipramine, and trazodone in a garden cress (Lepidium sativum) model. Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miszczak, E.; Stefaniak, S.; Cembrowska-Lech, D.; Skuza, L.; Twardowska, I. Effect of adaptation to high concentrations of cadmium on soil phytoremediation potential of the Middle European ecotype of a cosmopolitan cadmium hyperaccumulator Solanum nigrum L. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, G.; Peterson, A.; Zha, X.; Cheng, J.; Li, S.; Cui, D.; Zhu, H.; Kishchenko, O.; Borisjuk, N. Biodiversity of duckweeds in Eastern China and their potential for bioremediation of municipal and industrial wastewater. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2018, 6, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Pandey, B.; Suthar, S. Phytotoxicity of amoxicillin to the duckweed Spirodela polyrhiza: Growth, oxidative stress, biochemical traits and antibiotic degradation. Chemosphere 2018, 201, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meitei, M.D.; Prasad, M.N.V. Adsorption of Cu (II), Mn (II) and Zn (II) by Spirodela polyrhiza (L.) Schleiden: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 71, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, L.M.M.; Torres, G.; Arenas, A.D.; Sánchez, E.; Rodríguez, K. Phytoremediation of low levels of heavy metals using duckweed (Lemna minor). In Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants, 1st ed.; Ahmad, P., Prasad, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 413–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.J.; Williams, M.; Böttcher, C.; Kookana, R.S. Uptake of pharmaceuticals influences plant development and affects nutrient and hormone homeostases. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 12509–12518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodzic, E.; Galijasevic, S.; Balaban, M.; Rekanovic, S.; Makic, H.; Kukavica, B.; Mihajlovic, D. The protective role of melatonin under heavy metal-induced stress in Melissa officinalis L. Turk. J. Chem. 2021, 45, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, F.; Tang, M.; Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; Ying, J.; Chen, Y.; Hu, B.; Li, C.; Liu, L. Melatonin confers cadmium tolerance by modulating critical heavy metal chelators and transporters in radish plants. J. Pineal Res. 2020, 69, e12659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.W.; Armbrust, K.L. Laboratory persistence and fate of fluoxetine in aquatic environments. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006, 25, 2561–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Lemna sp. growth inhibition test. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 2—Effects on Biotic Systems; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2006; p. 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984, 105, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, Y.; Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981, 22, 867–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, C.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1971, 44, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacson, T.; Damasceno, C.M.; Saravanan, R.S.; He, Y.; Catalá, C.; Saladié, M.; Rose, J.K. Sample extraction techniques for enhanced proteomic analysis of plant tissues. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, I.A.; Amer, S.M.; Abdine, H.H.; Al-Rayes, L.I. New spectrophotometric and fluorimetric methods for determination of fluoxetine in pharmaceutical formulations. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2009, 2009, 257306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| C0 (mg L−1) | Cf L. minor (mg L−1) | Cf S. polyrhiza (mg L−1) |

|---|---|---|

| 5 Flu | 4.97 ± 0.02 d | 4.86 ± 0.04 d |

| 5 Flu + Ser | 3.73 ± 0.23 d | 3.55 ± 0.27 d |

| 10 Flu | 9.41 ± 0.26 cd | 9.45 ± 0.21 d |

| 10 Flu + Ser | 3.68 ± 0.55 d | 6.46 ± 0.39 d |

| 50 Flu | 40.40 ± 3.17 b | 43.02 ± 2.30 c |

| 50 Flu + Ser | 23.49 ± 5.22 c | 31.65 ± 3.62 c |

| 100 Flu | 69.14 ± 8.08 a | 85.85 ± 5.15 a |

| 100 Flu + Ser | 40.24 ± 7.64 b | 57.12 ± 7.13 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wierzbicka, M.; Michalczyk, D.J.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.I. Serotonin Application Decreases Fluoxetine-Induced Stress in Lemna minor and Spirodela polyrhiza. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010002

Wierzbicka M, Michalczyk DJ, Piotrowicz-Cieślak AI. Serotonin Application Decreases Fluoxetine-Induced Stress in Lemna minor and Spirodela polyrhiza. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleWierzbicka, Marta, Dariusz J. Michalczyk, and Agnieszka I. Piotrowicz-Cieślak. 2026. "Serotonin Application Decreases Fluoxetine-Induced Stress in Lemna minor and Spirodela polyrhiza" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010002

APA StyleWierzbicka, M., Michalczyk, D. J., & Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A. I. (2026). Serotonin Application Decreases Fluoxetine-Induced Stress in Lemna minor and Spirodela polyrhiza. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010002