Hormonal Interplay of GAs and Abscisic Acid in Rice Germination and Growth Under Low-Temperature Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

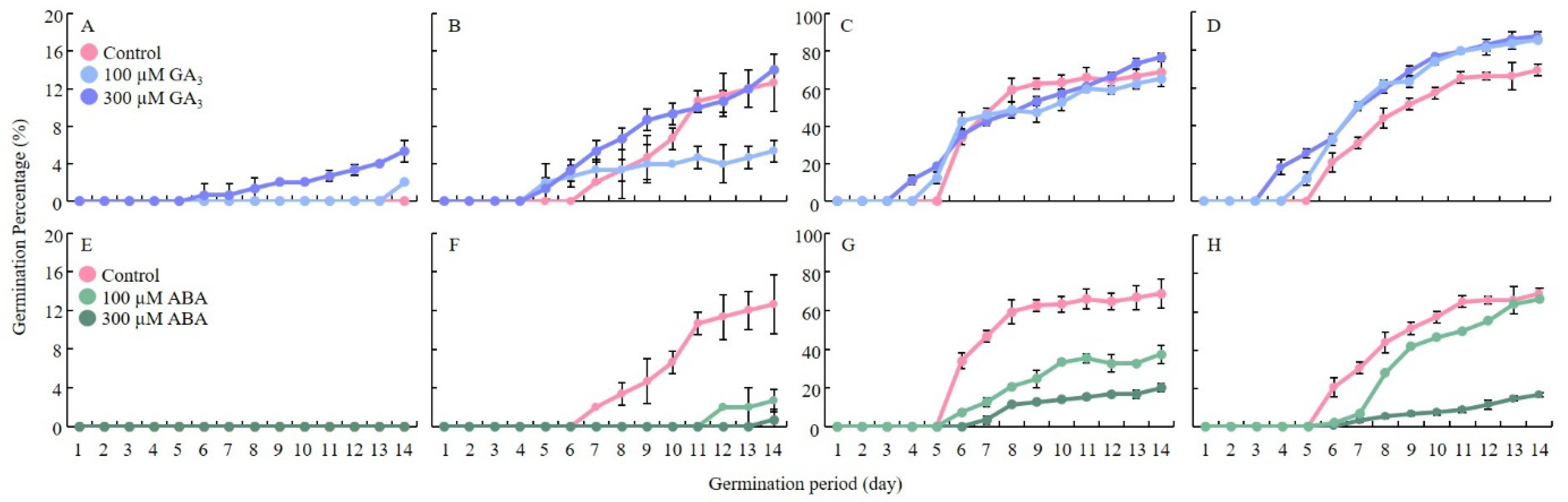

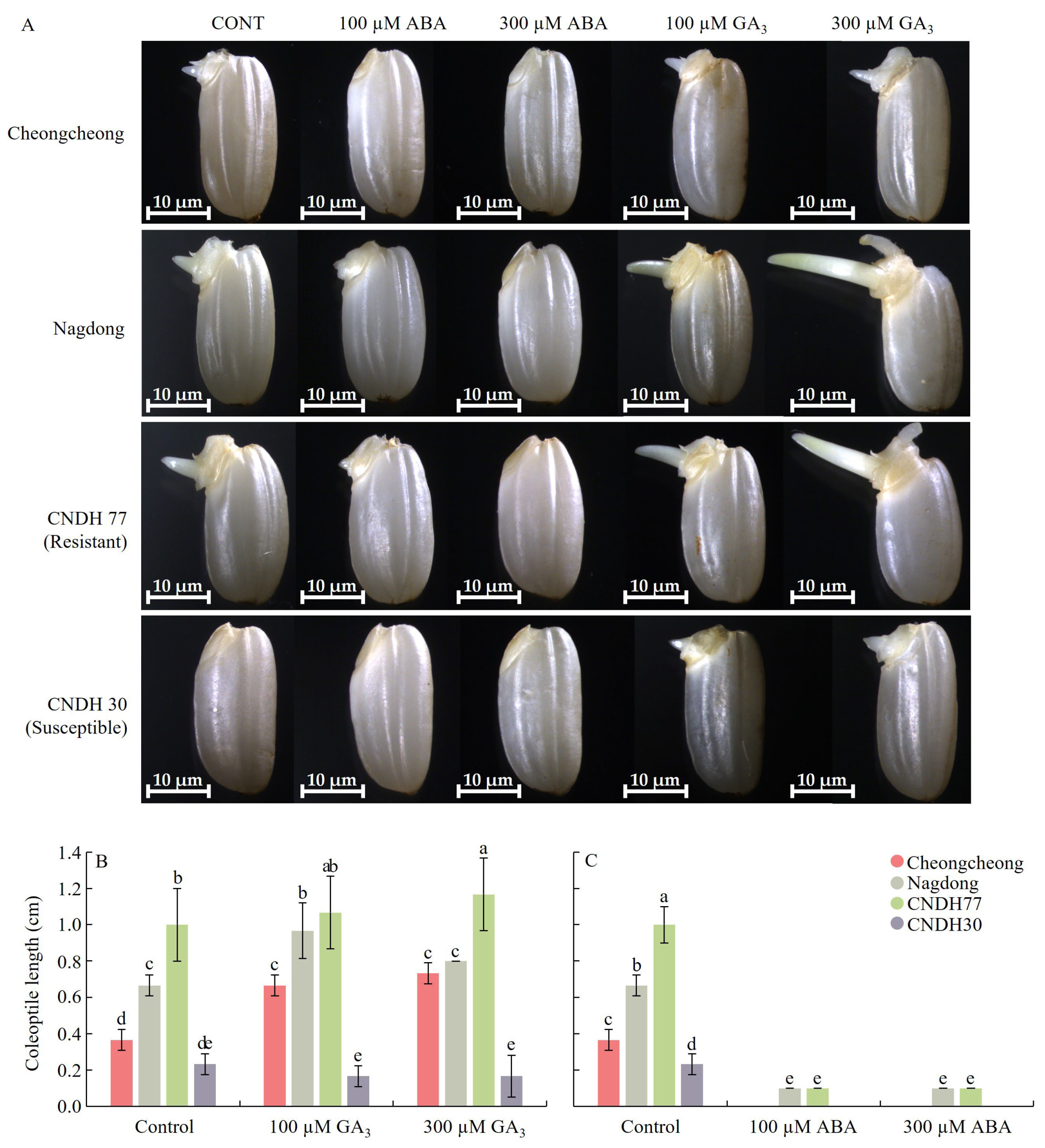

2.1. GA3 Promotes Germination and Growth, While ABA Inhibits Seed Germination

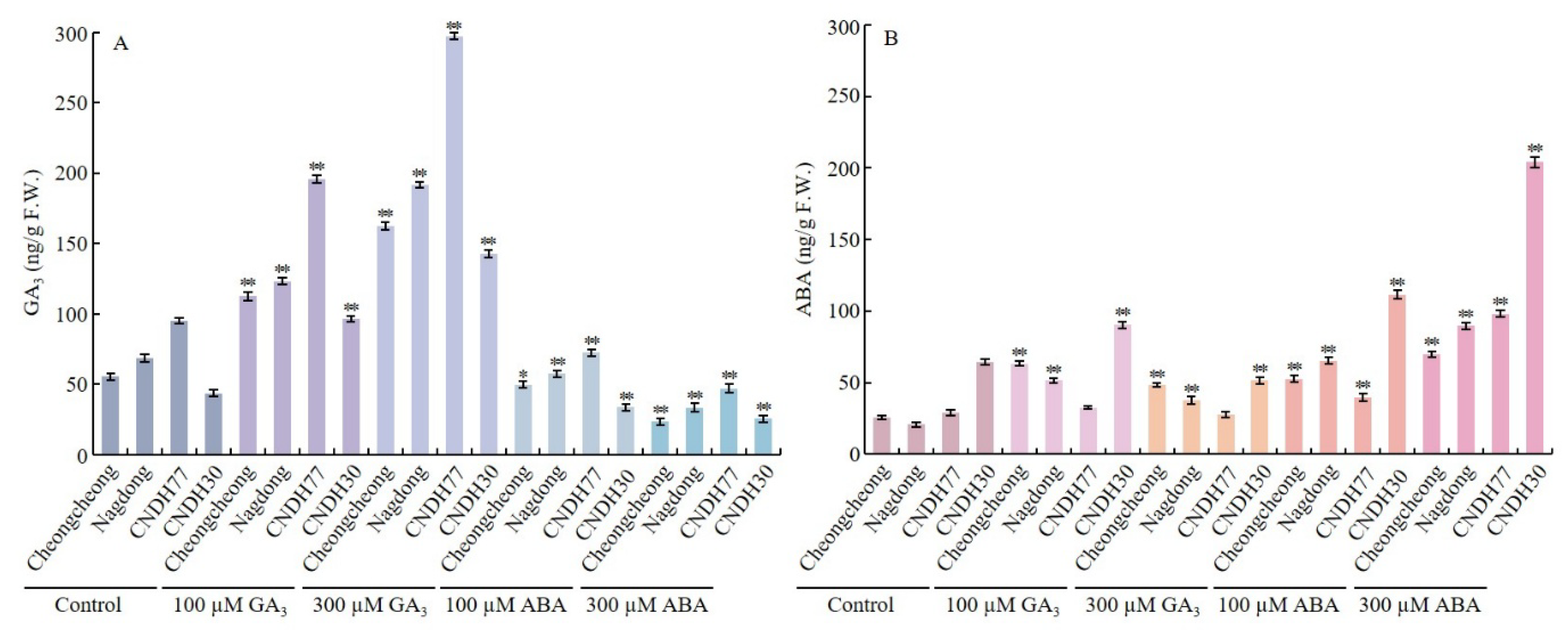

2.2. GA3 and ABA Modulate Endogenous Hormones in Rice Seeds Under Low-Temperature Stress

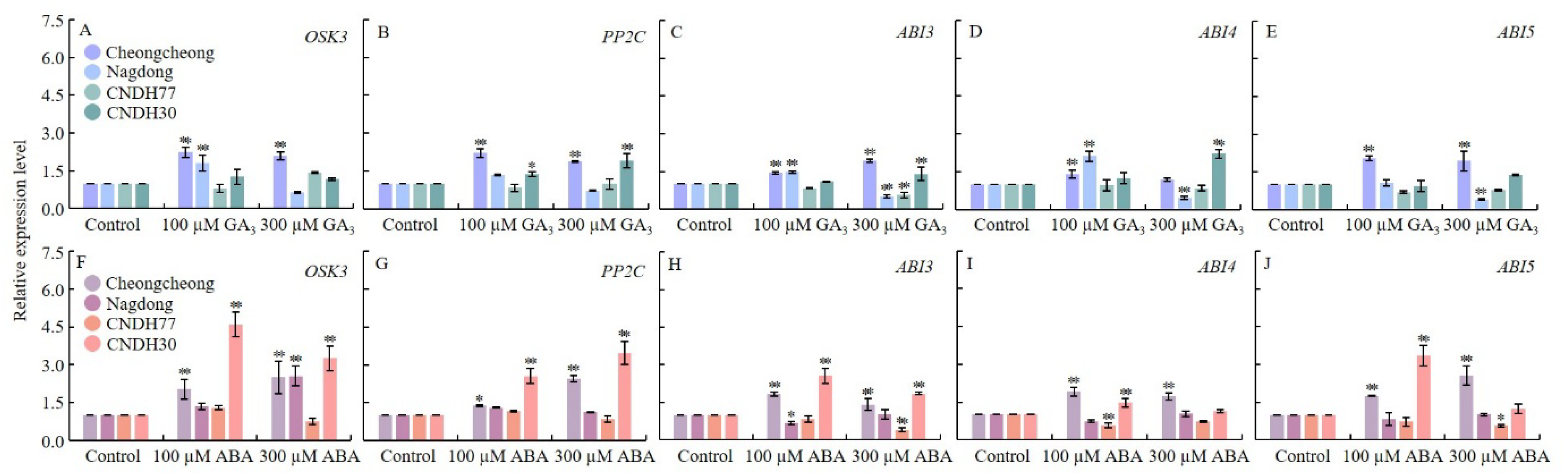

2.3. GA3 and ABA Modulate Key ABA Signaling Genes During Rice Seed Germination

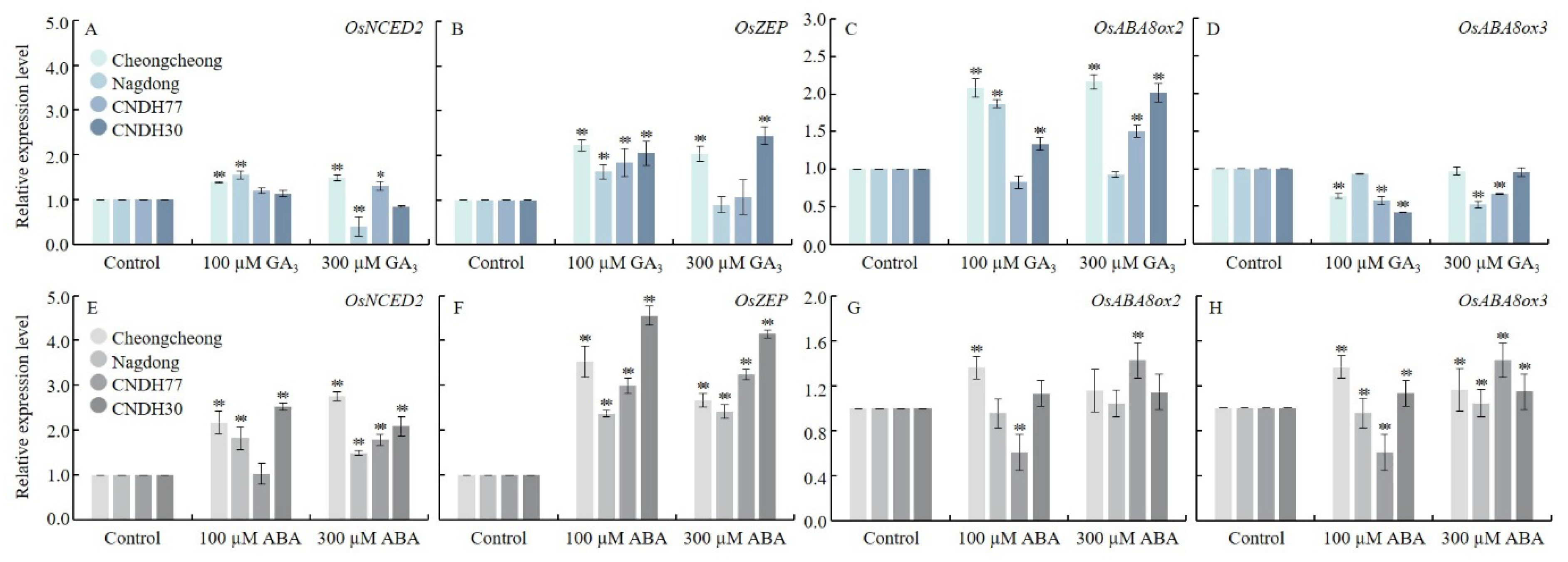

2.4. GA3 and ABA Regulate ABA Metabolism in Rice Seeds Under Low-Temperature Germination

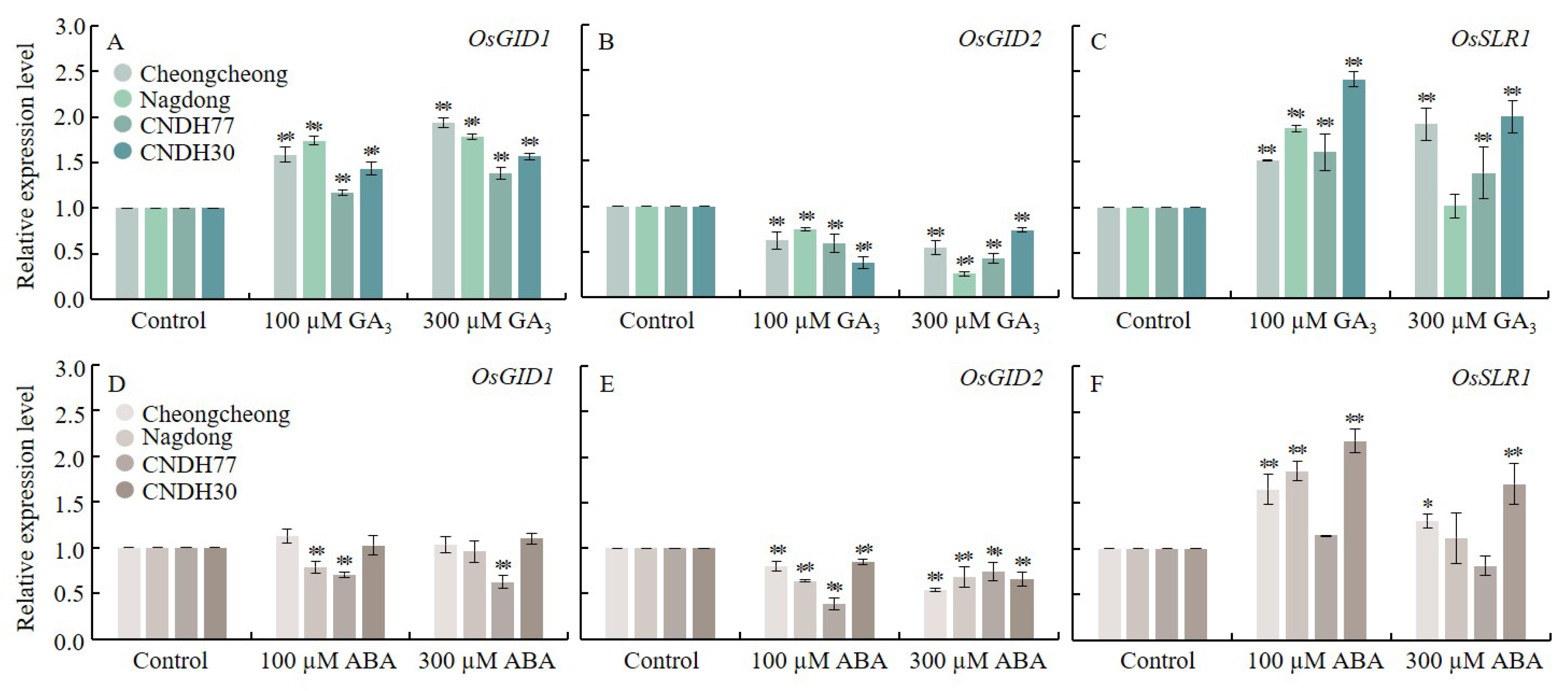

2.5. GA3 and ABA Alter GA Transduction Genes During Rice Seed Germination Under Low Temperatures

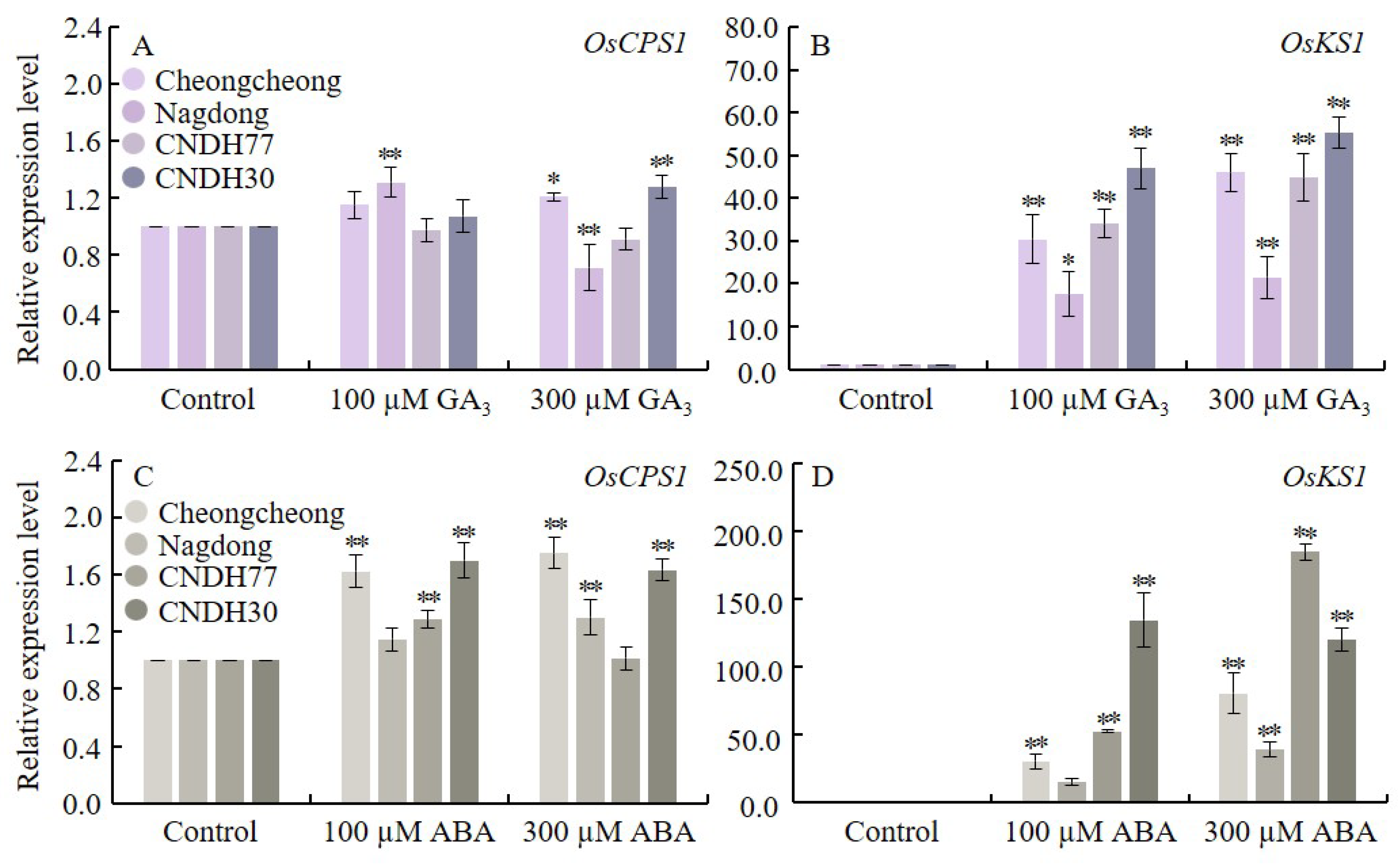

2.6. GA3 and ABA Regulate GA Biosynthesis Genes in Rice Seeds

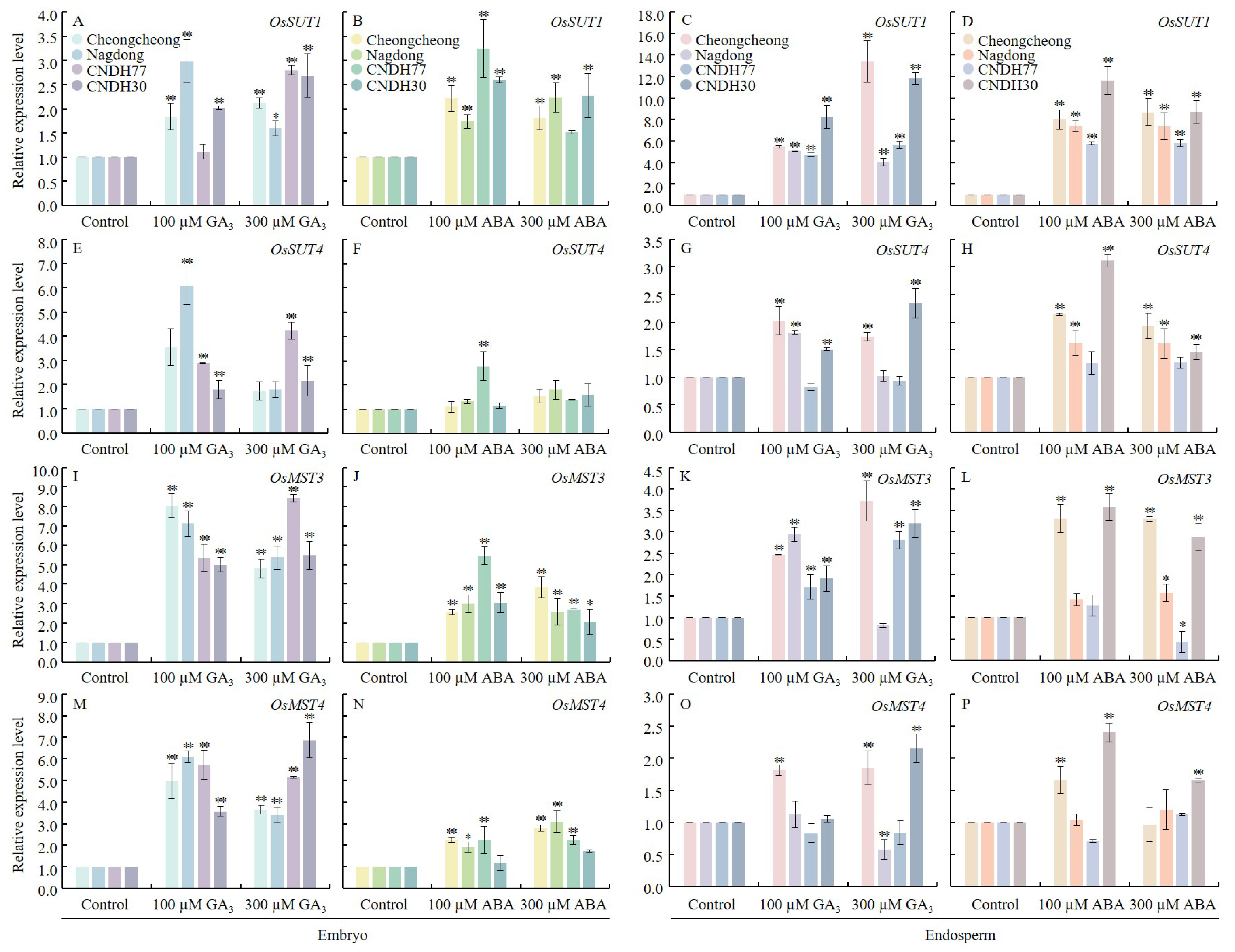

2.7. GA3 and ABA Modulate Sugar Transport and Accumulation in Rice Seed During Germination Under Low Temperatures

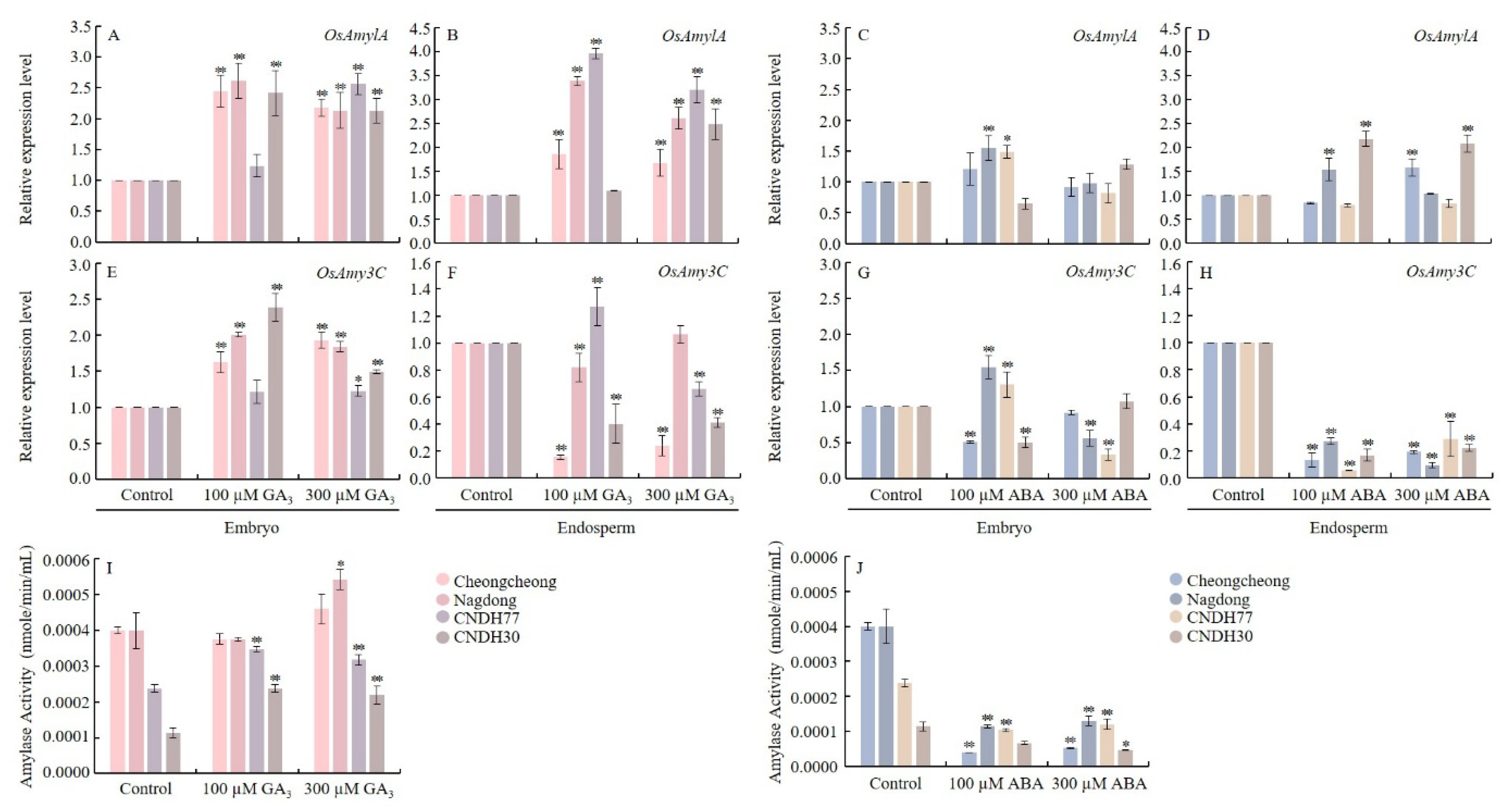

2.8. GA3 and ABA Regulate Amylase Activity and Related Gene Expression During Rice Seed Germination

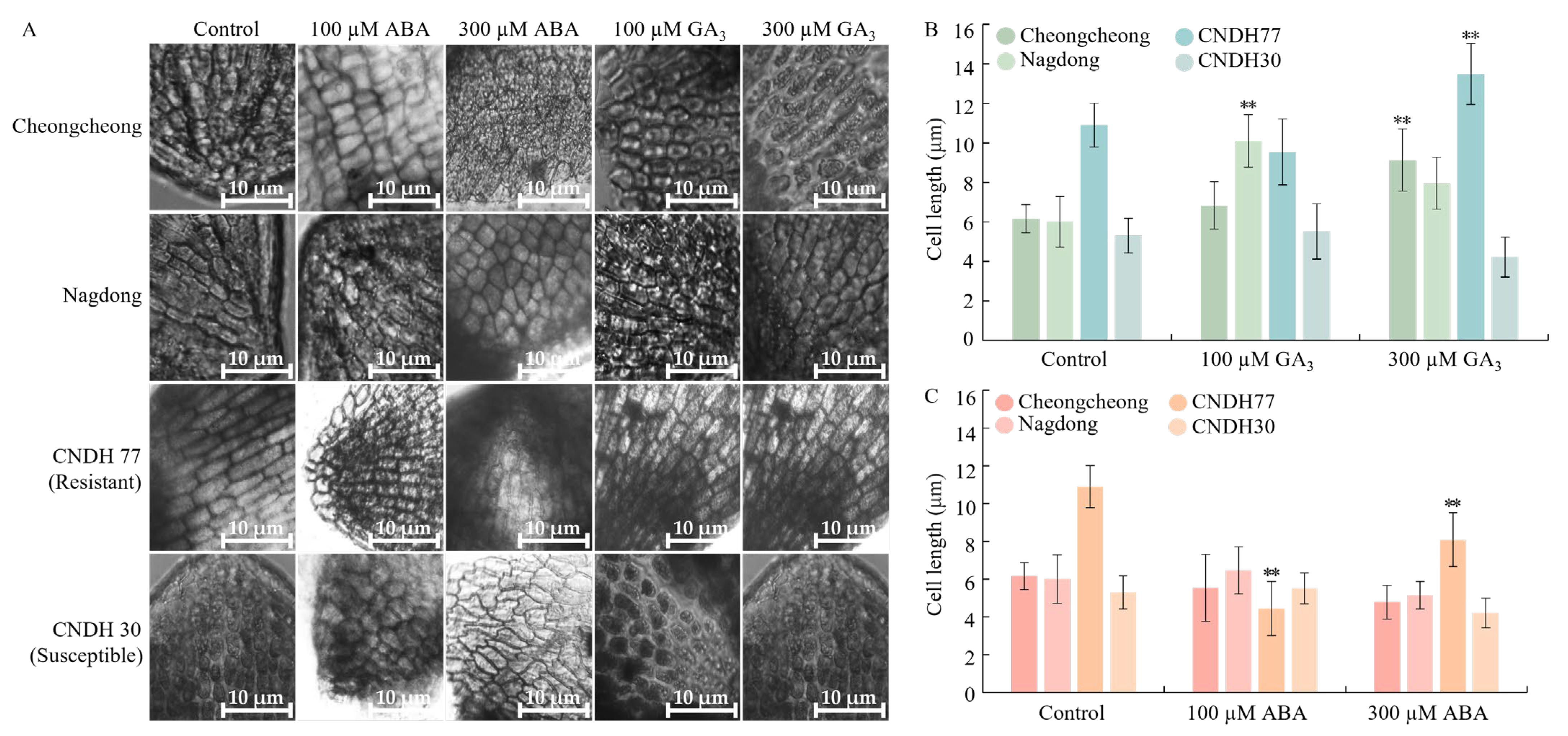

2.9. GA3 and ABA Modulate Cell Elongation in Rice Seed During Germination Under Low Temperatures

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Seed Germination Treatments

4.2. Seed Germination Percentage Measurement

4.3. Quantification of GA3 and ABA

4.4. Sugar Content, Coleoptile Length, and Cell Size Measurement

4.5. Amylase Activity Assay

4.6. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Makhaye, G.; Mofokeng, M.M.; Tesfay, S.; Aremu, A.O.; Van Staden, J.; Amoo, S.O. Influence of plant biostimulant application on seed germination. In Biostimulants for Crops from Seed Germination to Plant Development; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- Arana, M.V.; Gonzalez-Polo, M.; Martinez-Meier, A.; Gallo, L.A.; Benech-Arnold, R.L.; Sánchez, R.A.; Batlla, D. Seed dormancy responses to temperature relate to Nothofagus species distribution and determine temporal patterns of germination across altitudes in Patagonia. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Mota, L.A.S.; Garcia, Q.S. Germination patterns and ecological characteristics of Vellozia seeds from high-altitude sites in south-eastern Brazil. Seed Sci. Res. 2013, 23, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Khaliq, A.; Ali, B.; Hussain, H.A.; Qadir, T.; Hussain, S. Temperature extremes: Impact on rice growth and development. In Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance: Agronomic, Molecular and Biotechnological Approaches; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, X.; Tian, M.; Chen, J.; Chen, C.; Luo, Z.; Guo, T.; Huo, X.; Xiao, W. OsNAL11 and OsGASR9 Regulate the Low-Temperature Germination of Rice Seeds by Affecting GA Content. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najeeb, S.; Ali, J.; Mahender, A.; Pang, Y.; Zilhas, J.; Murugaiyan, V.; Vemireddy, L.R.; Li, Z. Identification of main-effect quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for low-temperature stress tolerance germination-and early seedling vigor-related traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol. Breed. 2020, 40, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.-S.; Huang, J.; Sun, A.-J.; Hong, X.-Z.; Zhu, L.-F.; Cao, X.-C.; Kong, Y.-L.; Jin, Q.-Y.; Zhu, C.-Q.; Zhang, J.-H. Effects of low temperature on the growth and development of rice plants and the advance of regulation pathways: A review. Chin. J. Rice Sci. 2022, 36, 118–130. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Cai, L.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z.; Guan, S.; Ma, W.; Pan, G. Low-temperature stress affects reactive oxygen species, osmotic adjustment substances, and antioxidants in rice (Oryza sativa L.) at the reproductive stage. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndour, D.; Diouf, D.; Bimpong, I.K.; Sow, A.; Kanfany, G.; Manneh, B. Agro-morphological evaluation of rice (Oryza sativa L.) for seasonal adaptation in the Sahelian environment. Agronomy 2016, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimono, H.; Hasegawa, T.; Iwama, K. Response of growth and grain yield in paddy rice to cool water at different growth stages. Field Crops Res. 2002, 73, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimono, H.; Okada, M.; Kanda, E.; Arakawa, I. Low temperature-induced sterility in rice: Evidence for the effects of temperature before panicle initiation. Field Crops Res. 2007, 101, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackill, D.J.; Lei, X. Genetic variation for traits related to temperate adaptation of rice cultivars. Crop Sci. 1997, 37, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.; Pearson, C. Cold damage and development of rice: A conceptual model. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1994, 34, 917–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, C.; Beachell, H. Response of indica-japonica rice hybrids to low temperatures. SABRAO J. Breed. Genet. 1974, 6, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Li, L. Hormonal regulation in shade avoidance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, N.; Zhang, G.; Wang, F.; Chen, X.; Fang, R. Rice GERMIN-LIKE PROTEIN 2-1 functions in seed dormancy under the control of abscisic acid and gibberellic acid signaling pathways. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.L.; Kim, H.; Bakshi, A.; Binder, B.M. The ethylene receptors ETHYLENE RESPONSE1 and ETHYLENE RESPONSE2 have contrasting roles in seed germination of Arabidopsis during salt stress. Plant Physiol. 2014, 165, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, R.; Reeves, W.; Ariizumi, T.; Steber, C. Molecular aspects of seed dormancy. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 387–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishal, B.; Kumar, P.P. Regulation of seed germination and abiotic stresses by gibberellins and abscisic acid. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karssen, C.; Brinkhorst-Van der Swan, D.; Breekland, A.; Koornneef, M. Induction of dormancy during seed development by endogenous abscisic acid: Studies on abscisic acid deficient genotypes of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Planta 1983, 157, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopfer, P.; Plachy, C. Control of Seed Germination by Abscisic Acid: II. Effect on Embryo Water Uptake in Brassica napus L. Plant Physiol. 1984, 76, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno-Gilles, C.; Lelièvre, E.; Viau, L.; Malik-Ghulam, M.; Ricoult, C.; Niebel, A.; Leduc, N.; Limami, A.M. ABA-mediated inhibition of germination is related to the inhibition of genes encoding cell-wall biosynthetic and architecture: Modifying enzymes and structural proteins in Medicago truncatula embryo axis. Mol. Plant 2009, 2, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, R.R.; Lynch, T.J. The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response gene ABI5 encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 599–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadman, C.S.; Toorop, P.E.; Hilhorst, H.W.; Finch-Savage, W.E. Gene expression profiles of Arabidopsis Cvi seeds during dormancy cycling indicate a common underlying dormancy control mechanism. Plant J. 2006, 46, 805–822, Erratum in Plant J. 2006, 47, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Blanco, C.; Bentsink, L.; Hanhart, C.J.; Vries, H.B.-d.; Koornneef, M. Analysis of natural allelic variation at seed dormancy loci of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 2003, 164, 711–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, N.; Abrams, S.R.; Kermode, A.R. Changes in ABA turnover and sensitivity that accompany dormancy termination of yellow-cedar (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis) seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, J.-K.; Ye, M.; Li, B.; Noel, J.P. Co-evolution of hormone metabolism and signaling networks expands plant adaptive plasticity. Cell 2016, 166, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushiro, T.; Okamoto, M.; Nakabayashi, K.; Yamagishi, K.; Kitamura, S.; Asami, T.; Hirai, N.; Koshiba, T.; Kamiya, Y.; Nambara, E. The Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 CYP707A encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylases: Key enzymes in ABA catabolism. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.; Hirai, N.; Matsumoto, C.; Ohigashi, H.; Ohta, D.; Sakata, K.; Mizutani, M. Arabidopsis CYP707A s encode (+)-abscisic acid 8′-hydroxylase, a key enzyme in the oxidative catabolism of abscisic acid. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 1439–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonai, T.; Kawahara, S.; Tougou, M.; Satoh, S.; Hashiba, T.; Hirai, N.; Kawaide, H.; Kamiya, Y.; Yoshioka, T. Abscisic acid in the thermoinhibition of lettuce seed germination and enhancement of its catabolism by gibberellin. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.P.; Koizuka, N.; Martin, R.C.; Nonogaki, H. The BME3 (Blue Micropylar End 3) GATA zinc finger transcription factor is a positive regulator of Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant J. 2005, 44, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfield, S.; Josse, E.-M.; Kannangara, R.; Gilday, A.D.; Halliday, K.J.; Graham, I.A. Cold and light control seed germination through the bHLH transcription factor SPATULA. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 1998–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kamiya, Y.; Bae, G.; Chung, W.I.; Choi, G. Light activates the degradation of PIL5 protein to promote seed germination through gibberellin in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006, 47, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, N.; Kim, W.; Lim, S.; Choi, G. ABI3 and PIL5 collaboratively activate the expression of SOMNUS by directly binding to its promoter in imbibed Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1404–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Murata, M.; Minami, H.; Yamamoto, S.; Kagaya, Y.; Hobo, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Hattori, T. Abscisic Acid-Activated SNRK2 Protein Kinases Function in the Gene-Regulation Pathway of ABA Signal Transduction by Phosphorylating ABA Response Element-Binding Factors. Plant J. 2005, 44, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-i.; Hong, J.-h.; Ha, J.-o.; Kang, J.-y.; Kim, S.Y. ABFs, a family of ABA-responsive element binding factors. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, J.; Dupeux, F.; Round, A.; Antoni, R.; Park, S.-Y.; Jamin, M.; Cutler, S.R.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Márquez, J.A. The abscisic acid receptor PYR1 in complex with abscisic acid. Nature 2009, 462, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Szostkiewicz, I.; Korte, A.; Moes, D.; Yang, Y.; Christmann, A.; Grill, E. Regulators of PP2C phosphatase activity function as abscisic acid sensors. Science 2009, 324, 1064–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Hu, G.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Shi, Q.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, Y. Reduced bioactive gibberellin content in rice seeds under low temperature leads to decreased sugar consumption and low seed germination rates. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 133, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M. The QTL Mapping of Low Temperature Germinability and Anoxia Germination in Rice (Oryza aativa L.). Doctoral Dissertation, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.; Jan, R.; Park, J.-R.; Asif, S.; Zhao, D.-D.; Kim, E.-G.; Jang, Y.-H.; Eom, G.-H.; Lee, G.-S.; Kim, K.-M. QTL mapping and candidate gene analysis for seed germination response to low temperature in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Nishimura, N.; Kitahata, N.; Kuromori, T.; Ito, T.; Asami, T.; Shinozaki, K.; Hirayama, T. ABA-hypersensitive germination3 encodes a protein phosphatase 2C (AtPP2CA) that strongly regulates abscisic acid signaling during germination among Arabidopsis protein phosphatase 2Cs. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraudat, J.; Hauge, B.M.; Valon, C.; Smalle, J.; Parcy, F.; Goodman, H.M. Isolation of the Arabidopsis ABI3 gene by positional cloning. Plant Cell 1992, 4, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, R.R.; Li Wang, M.; Lynch, T.J.; Rao, S.; Goodman, H.M. The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response locus ABI4 encodes an APETALA2 domain protein. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, D.; He, F.; Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Tian, S.; Sun, C.; Zhang, X. Understanding of hormonal regulation in rice seed germination. Life 2022, 12, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, A.; Chen, Z. The pivotal role of abscisic acid signaling during transition from seed maturation to germination. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.-K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Molina, L.; Mongrand, S.; McLachlin, D.T.; Chait, B.T.; Chua, N.H. ABI5 acts downstream of ABI3 to execute an ABA-dependent growth arrest during germination. Plant J. 2002, 32, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi, F.; Cordoba, E.; Dupré, P.; Mendoza, M.S.; Román, C.S.; León, P. The Arabidopsis ABA-INSENSITIVE (ABI) 4 factor acts as a central transcription activator of the expression of its own gene, and for the induction of ABI5 and SBE2. 2 genes during sugar signaling. Plant J. 2009, 59, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, T.; Oda, S.; Tsunaga, Y.; Shomura, H.; Kawagishi-Kobayashi, M.; Aya, K.; Saeki, K.; Endo, T.; Nagano, K.; Kojima, M. Reduction of gibberellin by low temperature disrupts pollen development in rice. Plant Physiol. 2014, 164, 2011–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Ye, N.; Zhang, J. Glucose-induced delay of seed germination in rice is mediated by the suppression of ABA catabolism rather than an enhancement of ABA biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Li, H.; Zhu, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Xu, W.; Jing, Y.; Peng, X.; Zhang, J. Copper suppresses abscisic acid catabolism and catalase activity, and inhibits seed germination of rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 2008–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambara, E.; Marion-Poll, A. Abscisic acid biosynthesis and catabolism. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005, 56, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, G.K.; Yamazaki, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Hirochika, R.; Miyao, A.; Hirochika, H. Screening of the rice viviparous mutants generated by endogenous retrotransposon Tos17 insertion. Tagging of a zeaxanthin epoxidase gene and a novel OsTATC gene. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 1248–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H.; Qin, X.; Zeevaart, J.A. Elucidation of the indirect pathway of abscisic acid biosynthesis by mutants, genes, and enzymes. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Andújar, C.; Ordiz, M.I.; Huang, Z.; Nonogaki, M.; Beachy, R.N.; Nonogaki, H. Induction of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase in Arabidopsis thaliana seeds enhances seed dormancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 17225–17229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, K.; Zhou, W.; Chen, F.; Luo, X.; Yang, W. Abscisic acid and gibberellins antagonistically mediate plant development and abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Khan, F.; Hussain, H.A.; Nie, L. Physiological and biochemical mechanisms of seed priming-induced chilling tolerance in rice cultivars. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.; Hsiao, H.-H.; Chen, H.-J.; Chang, C.-W.; Wang, S.-J. Influence of temperature on the expression of the rice sucrose transporter 4 gene, OsSUT4, in germinating embryos and maturing pollen. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2014, 36, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C.; Bogatek-Leszczynska, R.; Côme, D.; Corbineau, F. Changes in activities of antioxidant enzymes and lipoxygenase during growth of sunflower seedlings from seeds of different vigour. Seed Sci. Res. 2002, 12, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, M.; Wang, W. Effect of drought on the contents of soluble sugars, starch and enzyme activities in cassava stem. Plant Physiol. J 2017, 53, 795–806. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, S.; Gilroy, S. Abscisic acid signal transduction in the barley aleurone is mediated by phospholipase D activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2697–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.; Itoh, H.; Ueguchi-Tanaka, M.; Ashikari, M.; Matsuoka, M. The α-amylase induction in endosperm during rice seed germination is caused by gibberellin synthesized in epithelium. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleford, N.; Lenton, J. Hormonal regulation of α-amylase gene expression in germinating wheat (Triticum aestivum) grains. Physiol. Plant. 1997, 100, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, R.; Khan, M.A.; Asaf, S.; Lee, I.-J.; Bae, J.-S.; Kim, K.-M. Overexpression of OsCM alleviates BLB stress via phytohormonal accumulation and transcriptional modulation of defense-related genes in Oryza sativa. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboryia, M.; AL-Saoud, A.M.A.; El-Boraie, E.-S.A.; Abd El-Gawad, H.G.; Ismail, S.; Alkafafy, M.; Aljuaid, B.S.; Abu-Ziada, L.M. Seed germination, seedling growth performance, genetic stability and biochemical responses of papaya (Carica papaya L.) upon pre-sowing seed treatments. Folia Hort. 2024, 36, 533–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, R.; Khan, M.A.; Asaf, S.; Lee, I.-J.; Kim, K.-M. Modulation of sugar and nitrogen in callus induction media alter PAL pathway, SA and biomass accumulation in rice callus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. (PCTOC) 2020, 143, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Sahile, A.A.; Jan, R.; Asaf, S.; Hamayun, M.; Imran, M.; Adhikari, A.; Kang, S.-M.; Kim, K.-M.; Lee, I.-J. Halotolerant bacteria mitigate the effects of salinity stress on soybean growth by regulating secondary metabolites and molecular responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, N.; Jan, R.; Asif, S.; Asaf, S.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, K.-M. Hormonal Interplay of GAs and Abscisic Acid in Rice Germination and Growth Under Low-Temperature Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010181

Kim N, Jan R, Asif S, Asaf S, Kim HY, Kim K-M. Hormonal Interplay of GAs and Abscisic Acid in Rice Germination and Growth Under Low-Temperature Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010181

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Nari, Rahmatullah Jan, Saleem Asif, Sajjad Asaf, Hak Yoon Kim, and Kyung-Min Kim. 2026. "Hormonal Interplay of GAs and Abscisic Acid in Rice Germination and Growth Under Low-Temperature Stress" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010181

APA StyleKim, N., Jan, R., Asif, S., Asaf, S., Kim, H. Y., & Kim, K.-M. (2026). Hormonal Interplay of GAs and Abscisic Acid in Rice Germination and Growth Under Low-Temperature Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010181