The Association Between miRNA-223-3p Levels and Pain Severity in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Molecular Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Demographic Data

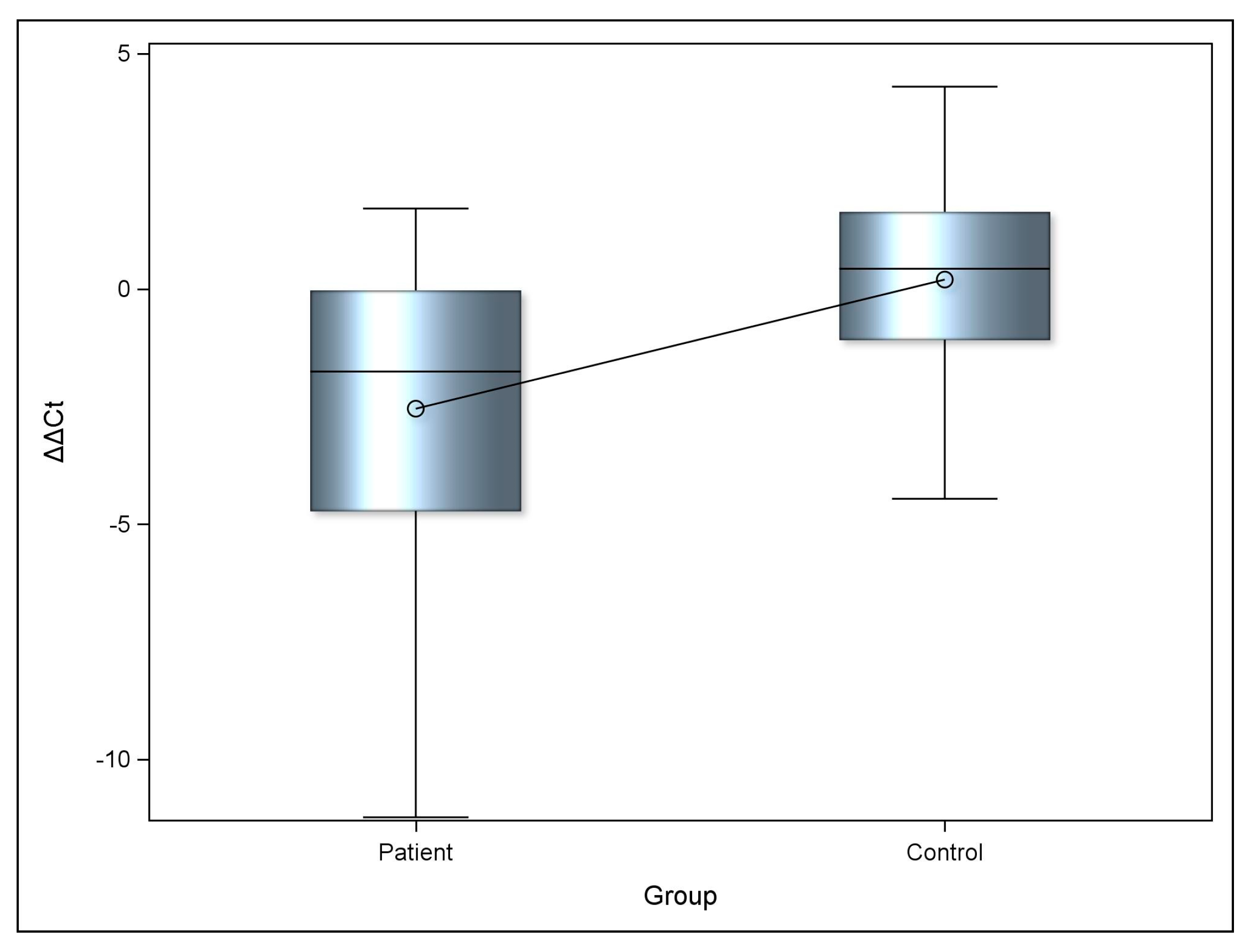

2.2. miRNA-223-3p Expression Levels

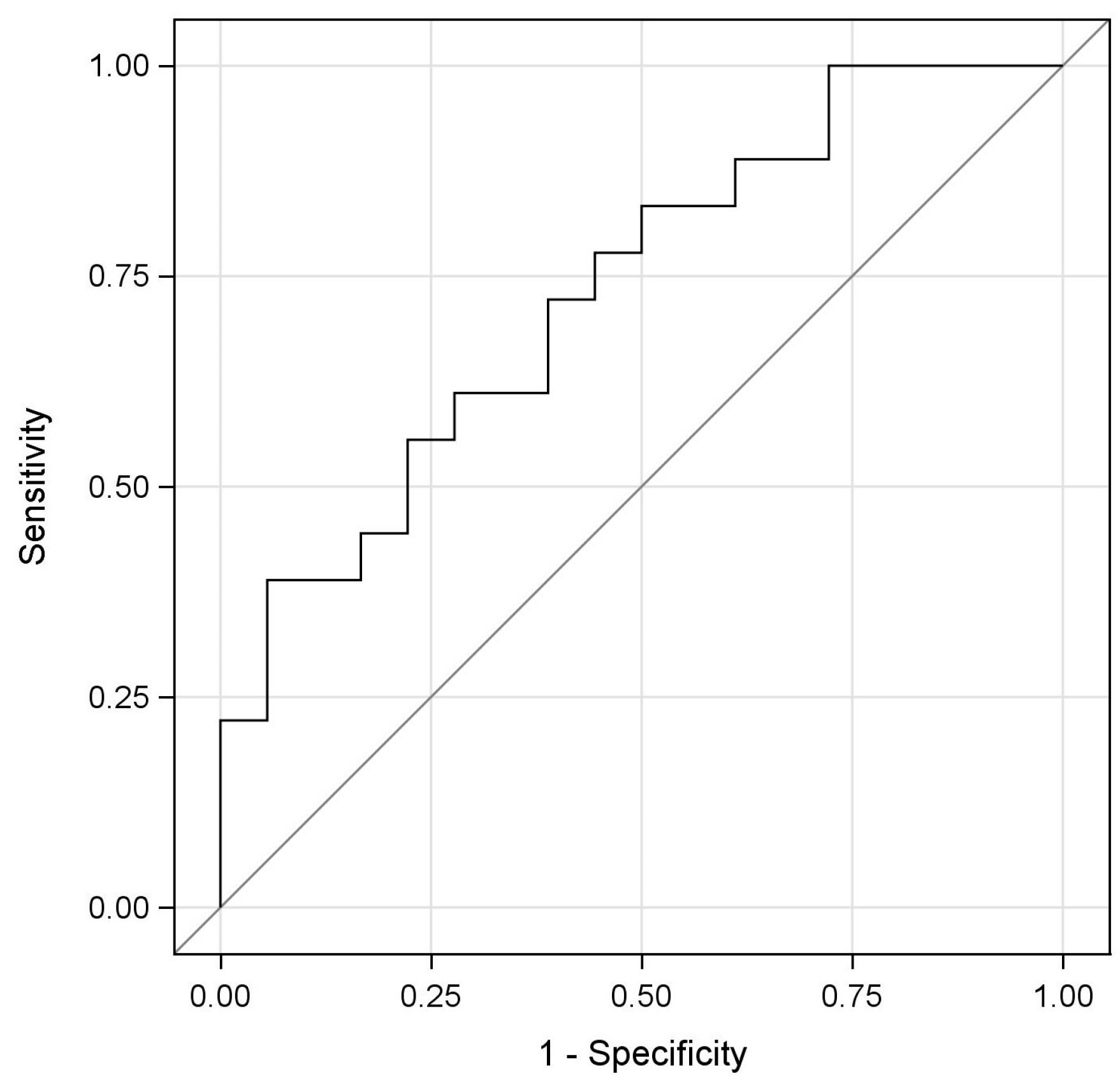

2.3. Evaluation of the Diagnostic Potential of miRNA-223-3p (ROC Analysis)

2.4. IL-1β Serum Values

2.5. Correlation Between VAS, BMI, IL-1β and miRNA-223-3p Expression Levels

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Sampling

4.2. Case and Control Groups

- Age over 18 years.

- Voluntary participation with a confirmed diagnosis of FMS.

- Infectious or inflammatory disease.

- Chronic diseases.

- Neurological or Psychiatric disorder.

- Active use of analgesic, antidepressant, or anti-inflammatory medications.

- Chronic fatigue syndrome or other pain syndromes.

- Pregnancy.

- Antibiotic use within the last three months.

4.3. Data Collection Methods

Assessment of Pain Severity

4.4. miRNA-223-3p Expression Analysis

4.5. Measurement of Serum IL-1β Levels by ELISA

4.6. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FMS | Fibromyalgia Syndrome |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| NLRP3 | NOD-like receptor protein 3 |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead box protein O1 |

| FBXW7 | F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7 |

| SORBS1 | Sorbin and SH3 domain-containing protein 1. |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| NF-Κb | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal Fluid |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristics |

| FIQ | Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire |

| MNK2 | MAP kinase-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 2 |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

References

- Bair, M.J.; Krebs, E.E. Fibromyalgia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, ITC33–ITC48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaslan, E.; Güvener, O.; Görür, A.; Çelikcan, D.H.; Tamer, L.; Biçer, A. The Plasma microRNA Levels and Their Relationship with the General Health and Functional Status in Female Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Arch. Rheumatol. 2021, 36, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terol Cantero, M.C.; Buunk, A.P.; Cabrera, V.; Bernabé, M.; Martin-Aragón Gelabert, M. Profiles of Women with Fibromyalgia and Social Comparison Processes. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjersing, J.L.; Bokarewa, M.I.; Mannerkorpi, K. Profile of Circulating microRNAs in Fibromyalgia and Their Relation to Symptom Severity: An Exploratory Study. Rheumatol. Int. 2015, 35, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjersing, J.L.; Lundborg, C.; Bokarewa, M.I.; Mannerkorpi, K. Profile of Cerebrospinal microRNAs in Fibromyalgia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siracusa, R.; Di Paola, R.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Impellizzeri, D. Fibromyalgia: Pathogenesis, Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Treatment Options Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, M.D. Oxidative Stress in Fibromyalgia: Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. Reumatol. Clin. 2011, 7, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauw, D.J. Fibromyalgia: An Overview. Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, S3–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masotti, A.; Baldassarre, A.; Guzzo, M.P.; Iannuccelli, C.; Barbato, C.; Di Franco, M. Circulating microRNA Profiles as Liquid Biopsies for the Characterization and Diagnosis of Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 7129–7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, A.; Suzuki, H. Emerging Roles of microRNAs in Chronic Pain. Neurochem. Int. 2014, 77, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidian, M.H.; Tilleman, J. Treatment Approaches for Fibromyalgia. U.S. Pharm. 2021, 46, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Häuser, W.; Katz, R.L.; Mease, P.J.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Walitt, B. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2016, 46, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Albaş, S.; Küçükerdem, H.; Pamuk, G.; Can, H. The Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Palliative Pain Management in Cancer Patients with Visual Analogue Scale. Fam. Pract. Palliat. Care 2016, 1, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, O.; Segal, R.; Maslakov, I.; Markov, A.; Tishler, M.; Amit-Vazina, M. The Impact of Concomitant Fibromyalgia on Visual Analogue Scales of Pain, Fatigue and Function in Patients with Various Rheumatic Disorders. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2016, 34, S120–S124. [Google Scholar]

- Clauw, D.J.; Arnold, L.M.; McCarberg, B.H. The Science of Fibromyalgia. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011, 86, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denk, F.; McMahon, S.B. Chronic Pain: Emerging Evidence for the Involvement of Epigenetics. Neuron 2012, 73, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, S.; Delay, M.; Macian, N.; Morel, V.; Pickering, M.E. Common miRNAs of Osteoporosis and Fibromyalgia: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polli, A.; Godderis, L.; Ghosh, M.; Ickmans, K.; Nijs, J. Epigenetic and miRNA Expression Changes in People with Pain: A Systematic Review. J. Pain 2020, 21, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalanotto, C.; Cogoni, C.; Zardo, G. MicroRNA in Control of Gene Expression: An Overview of Nuclear Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emde, A.; Hornstein, E. miRNAs at the Interface of Cellular Stress and Disease. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 1428–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhold, A.K.; Kindl, G.K.; Dietz, C.; Scheu, N.; Mehling, K.; Brack, A.; Birklein, F.; Rittner, H.L. Molecular and Clinical Markers of Pain Relief in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: An Observational Study. Eur. J. Pain 2023, 27, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf-Eldin, W.E.; Kishk, N.A.; Gad, Y.Z.; Hassan, H.; Ali, M.A.M.; Zaki, M.S.; Mohamed, M.R.; Essawi, M.L. Extracellular miR-145, miR-223 and miR-326 Expression Signature Allow for Differential Diagnosis of Immune-Mediated Neuroinflammatory Diseases. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017, 383, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.H.; Pao, Y.Y.; Cheng, J.K.; Hung, K.C.; Liu, C.C. MicroRNA-Based Therapy in Pain Medicine: Current Progress and Future Prospects. Acta Anaesthesiol. Taiwanica 2013, 51, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasulova, K.; Pehlivan, M.; Dilek, B.; Kızıldağ, S. Fibromiyalji Sendromu Olan Hastalarda miRNA Profillerinin Rolü ve Önemi. Med. J. Süleyman Demirel Univ. 2021, 28, 529–533. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.H. MicroRNA Networks Modulate Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Jiang, B.H. Interplay between Reactive Oxygen Species and microRNAs in Cancer. Curr. Pharmacol. Rep. 2016, 2, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnnidis, J.B.; Harris, M.H.; Wheeler, R.T.; Stehling-Sun, S.; Lam, M.H.; Kirak, O.; Brummelkamp, T.R.; Fleming, M.D.; Camargo, F.D. Regulation of Progenitor Cell Proliferation and Granulocyte Function by microRNA-223. Nature 2008, 451, 1125–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Dong, X.; Wang, K.; Shi, J.; Sun, N. Electroacupuncture Inhibits Autophagy of Neuron Cells in Postherpetic Neuralgia by Increasing the Expression of miR-223-3p. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6637693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, D.P.; Eriksen, M.B.; Rajalingam, D.; Nymoen, I.; Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S.; Gjerstad, J. Exposure to Workplace Bullying, microRNAs and Pain; Evidence of a Moderating Effect of miR-30c rs928508 and miR-223 rs3848900. Stress 2019, 23, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauernfeind, F.; Rieger, A.; Schildberg, F.A.; Knolle, P.A.; Schmid-Burgk, J.L.; Hornung, V. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity Is Negatively Controlled by miR-223. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 4175–4181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvente, C.J.; Del Pilar, H.; Tameda, M.; Johnson, C.D.; Feldstein, A.E. MicroRNA-223-3p Negatively Regulates the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Acute and Chronic Liver Injury. Mol. Ther. 2020, 28, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Deng, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, M.; Huang, Y. MiR-223-3p Expression in Deep Second-Degree Burn and its Role in the Wound Healing Process. J. Burn Care Res. 2025, 46, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Li, P.; Du, L.; Wang, C. miR-223-3p Targets FBXW7 to Promote Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Metastasis in Breast Cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2022, 13, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Qiu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, K. miR-223-3p Carried by Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Microvesicles Targets SORBS1 to Modulate the Progression of Gastric Cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 96, Correction in Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Bie, B.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Sheng, L.; Li, M. MiR-223-3p Promote Microglia “M2” Polarization by Targeting FOXO3a in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. J. Neuroimmunol. 2025, 406, 578677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, P.; Lin, C.; Chen, M.; Zhu, S.; Huang, L.; He, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. miR-223-3p Alleviates Trigeminal Neuropathic Pain in the Male Mouse by Targeting MKNK2 and MAPK/ERK Signaling. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harraz, M.M.; Eacker, S.M.; Wang, X.; Dawson, T.M.; Dawson, V.L. microRNA-223 Is Neuroprotective by Targeting Glutamate Receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 18962–18967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, T.; Liu, N.; Yang, L.; Liu, C.; Qi, X.; Wang, N.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y. miR-223-3p Inhibits Hippocampal Neurons Injury and Exerts Anti-Anxiety/Depression-like Behaviors by Directly Targeting NLRP3. Psychopharmacology 2025, 242, 1797–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.E.; Becerril, E.; Perez, M.; Leff, P.; Anton, B.; Estrada, S.; Estrada, I.; Sarasa, M.; Serrano, E.; Pavon, L. Proinflammatory Cytokine Levels in Fibromyalgia Patients Are Independent of Body Mass Index. BMC Res. Notes 2010, 3, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, K.; Torres, R. Role of Interleukin-1β during Pain and Inflammation. Brain Res. Rev. 2009, 60, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemi, S.; Rethage, J.; Wollina, U.; Michel, B.A.; Gay, R.E.; Gay, S.; Sprott, H. Detection of Interleukin 1beta (IL-1beta), IL-6, and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha in Skin of Patients with Fibromyalgia. J. Rheumatol. 2003, 30, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, M.M.; Maram, R.; Mohamed, A.; Crespo, D.O.; Kaur, G.; Ashraf, I.; Malik, B.H. The Influence of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and Genetic Variants in the Development of Fibromyalgia: A Traditional Review. Cureus 2020, 12, e10276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazlikul, H.; Nazlikul, U. Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS): Neural Therapy as a Key to Pain Reduction and Quality of Life. Int. Clin. Med. Case Rep. J. 2025, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Muzammil, S.; Cooper, H.C. Acute Pancreatitis and Fibromyalgia: Cytokine Link. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2011, 3, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-B.; Zhu, D.; Dai, F.; Huang, Y.-Q.; Zheng, J.-X.; Tang, Y.-P.; Dong, Z.-R.; Liao, X.; Qing, Y.-F. MicroRNA-223 Suppresses IL-1β and TNF-α Production in Gouty Inflammation by Targeting the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 637415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P.Y. The NLRP3 Inflammasome: Molecular Activation and Regulation to Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Zang, Y.; Wang, F. NLRP3 Inflammasome Inactivation Driven by miR-223-3p Reduces Tumor Growth and Increases Anticancer Immunity in Breast Cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 19, 2180–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Kong, X.; Song, M.; Chi, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Shang, P.; Feng, F. MiR-223-3p Attenuates the Migration and Invasion of NSCLC Cells by Regulating NLRP3. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 985962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Yao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, X.; Su, H. LncRNA KCNQ1OT1 Promoted Hepatitis C Virus-Induced Pyroptosis of β-Cell through Mediating the miR-223-3p/NLRP3 Axis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepple, D.D.; Thornburg, T.E.; Beckman, M.F.; Bahrani Mougeot, F.; Mougeot, J.C. Elucidating Regulatory Mechanisms of Genes Involved in Pathobiology of Sjögren’s Disease: Immunostimulation Using a Cell Culture Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, J.; Goldin, J. Fibromyalgia. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Legfeldt, A. Role of microRNA-223 in Pain Modulation. Master’s Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, C.; Müller, M.; Reinhold, A.-K.; Karch, L.; Schwab, B.; Forer, L.; Vlckova, E.; Brede, E.-M.; Jakubietz, R.; Üçeyler, N.; et al. What Is Normal Trauma Healing and What Is Complex Regional Pain Syndrome I? An Analysis of Clinical and Experimental Biomarkers. Pain 2019, 160, 2278–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moen, A.; Jacobsen, D.; Phuyal, S.; Legfeldt, A.; Haugen, F.; Røe, C.; Gjerstad, J. microRNA-223 Demonstrated Experimentally in Exosome-Like Vesicles Is Associated with Decreased Risk of Persistent Pain after Lumbar Disc Herniation. J. Transl. Med. 2017, 15, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Shen, L.; Nie, X.; Lu, B.; Pan, X.; Su, Z.; Yan, A.; Yan, R.; Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; et al. MiR-223-3p Overexpression Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Migration by Regulating Inflammation-Associated Cytokines in Glioblastomas. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2018, 214, 1330–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Dong, X.; Li, Y.; Tong, S.; Wang, J.; Liao, M.; Huang, G. Deep Sequencing Identification of Differentially Expressed miRNAs in the Spinal Cord of Resiniferatoxin-Treated Rats in Response to Electroacupuncture. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 36, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.K.; Sarria, L.; Bekheit, M.; Collado, F.; Almenar-Pérez, E.; Martín-Martínez, E.; Alegre, J.; Castro Marrero, J.; Fletcher, M.A.; Klimas, N.G.; et al. Unravelling Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Gender-Specific Changes in the microRNA Expression Profiling in ME/CFS. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 5865–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhazaali-Ali, Z.; Sahab-Negah, S.; Boroumand, A.R.; Tavakol-Afshari, J. microRNA (miRNA) as a Biomarker for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutics Molecules in Neurodegenerative Disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 116899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá-Olmedo, G.; Mena-Durán, A.V.; Monsalve, V.; Oltra, E. Identification of a microRNA Signature for the Diagnosis of Fibromyalgia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzaki, J.; Ochiya, T. Extracellular microRNAs and Oxidative Stress in Liver Injury: A Systematic Mini Review. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2018, 63, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.M.; Deng, J.J.; Wu, Y.G.; Tang, T.; Xiong, L.; Zheng, Y.F.; Xu, X.M. microRNA-223-3p Protects against Radiation-Induced Cardiac Toxicity by Alleviating Myocardial Oxidative Stress and Programmed Cell Death via Targeting the AMPK Pathway. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 801661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Agnelli, S.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Gerra, M.C.; Zatorri, K.; Boggiani, L.; Baciarello, M.; Bignami, E. Fibromyalgia: Genetics and Epigenetics Insights May Provide the Basis for the Development of Diagnostic Biomarkers. Mol. Pain 2019, 15, 1744806918819944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, B.; Cê, P.; Silva, R.; Oliveira, R.; Heitz, C.; Campos, M. Salivary Levels of Interleukin-1β in Temporomandibular Disorders and Fibromyalgia. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ögüt, Ö.G.Ü.T.; Gür, A. Monocyte Expression Levels of Cytokines in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Arch. Rheumatol. 2015, 30, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdolap, S.; Kutu, F.C. AB0948 Proinflammatory Cytokine and OX-LDL Levels in Fibromyalgia Patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Park, S.H.; Choe, J.Y. Arterial Stiffness and Proinflammatory Cytokines in Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2010, 28, S71–S77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ernberg, M.; Christidis, N.; Ghafouri, B.; Bileviciute-Ljungar, I.; Löfgren, M.; Bjersing, J.; Palstam, A.; Larsson, A.; Mannerkorpi, K.; Gerdle, B.; et al. Plasma Cytokine Levels in Fibromyalgia and Their Response to 15 Weeks of Progressive Resistance Exercise or Relaxation Therapy. Mediators Inflamm. 2018, 2018, 3985154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordero, M.D.; Alcocer-Gómez, E.; Culic, O.; Carrión, A.M.; De Miguel, M.; Díaz-Parrado, E.; Pérez-Villegas, E.M.; Bullón, P.; Battino, M.; Sánchez-Alcazar, J.A. NLRP3 Inflammasome Is Activated in Fibromyalgia: The Effect of Coenzyme Q10. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareja, J.L.; Martín, F.; Berná, G.; Cáceres, O.; Blanco, M.; Prada, F.A.; Berral, F.J. Fibromyalgia: A Search for Markers and Their Evaluation throughout a Treatment. Eur. Sci. J. 2015, 11, 426–434. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.E.; Barkhuizen, A. Fibromyalgia, Hepatitis C Infection, and the Cytokine Connection. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2003, 7, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 29 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Patient | Control | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | 0.2777 1 | ||

| Male | 4 (22.2%) | 7 (38.9%) | |

| Female | 14 (77.8%) | 11 (61.1%) | |

| Age | 0.6806 2 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 46.2 (11.64) | 48.5 (12.12) | |

| Median (Range) | 45.5 (23.0, 73.0) | 47.0 (27.0, 73.0) | |

| BMI | 0.1455 2 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 28.1 (5.02) | 26.0 (4.16) | |

| Median (Range) | 26.8 (19.5, 37.8) | 24.6(21.3, 40.0) | |

| VAS score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.1 (1.43) | ||

| Median (Range) | 8.0 (5.0, 10.0) |

| ΔΔCT | Patient | Control | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | −2.5 (3.3) | 0.2 (2.52) | 0.0176 * |

| Median (Range) | −1.8 (−11.2, 1.7) | 0.4 (−4.5, 4.3) |

| AUC | SE | 95%CI | p | Cut Off | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆∆Ct | 0.731 | 0.083 | 0.569 | 0.894 | 0.005 | 0.96 | 0.389 | 0.944 |

| BMI | VAS | miRNA-223-3p | IL-1β | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | 1.0000 | |||

| VAS | 0.3343 | 1.0000 | ||

| 0.1751 | ||||

| miRNA-223-3p | −0.1915 | −0.6699 | 1.0000 | |

| 0.2630 | 0.0024 | |||

| IL-1β | 0.0315 | −0.0485 | 0.0192 | 1.0000 |

| 0.9012 | 0.8489 | 0.9394 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Barut, Z.; Karataş, Ö.; Akdeniz, F.T.; Çırçırlı, B.; Demir, S.; İsbir, T. The Association Between miRNA-223-3p Levels and Pain Severity in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Molecular Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010176

Barut Z, Karataş Ö, Akdeniz FT, Çırçırlı B, Demir S, İsbir T. The Association Between miRNA-223-3p Levels and Pain Severity in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Molecular Approach. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010176

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarut, Zerrin, Özlem Karataş, Fatma Tuba Akdeniz, Bürke Çırçırlı, Serpil Demir, and Turgay İsbir. 2026. "The Association Between miRNA-223-3p Levels and Pain Severity in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Molecular Approach" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010176

APA StyleBarut, Z., Karataş, Ö., Akdeniz, F. T., Çırçırlı, B., Demir, S., & İsbir, T. (2026). The Association Between miRNA-223-3p Levels and Pain Severity in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Molecular Approach. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010176