Integrating Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) and Marker-Assisted Selection for Enhanced Predictive Performance of Soybean Cold Tolerance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

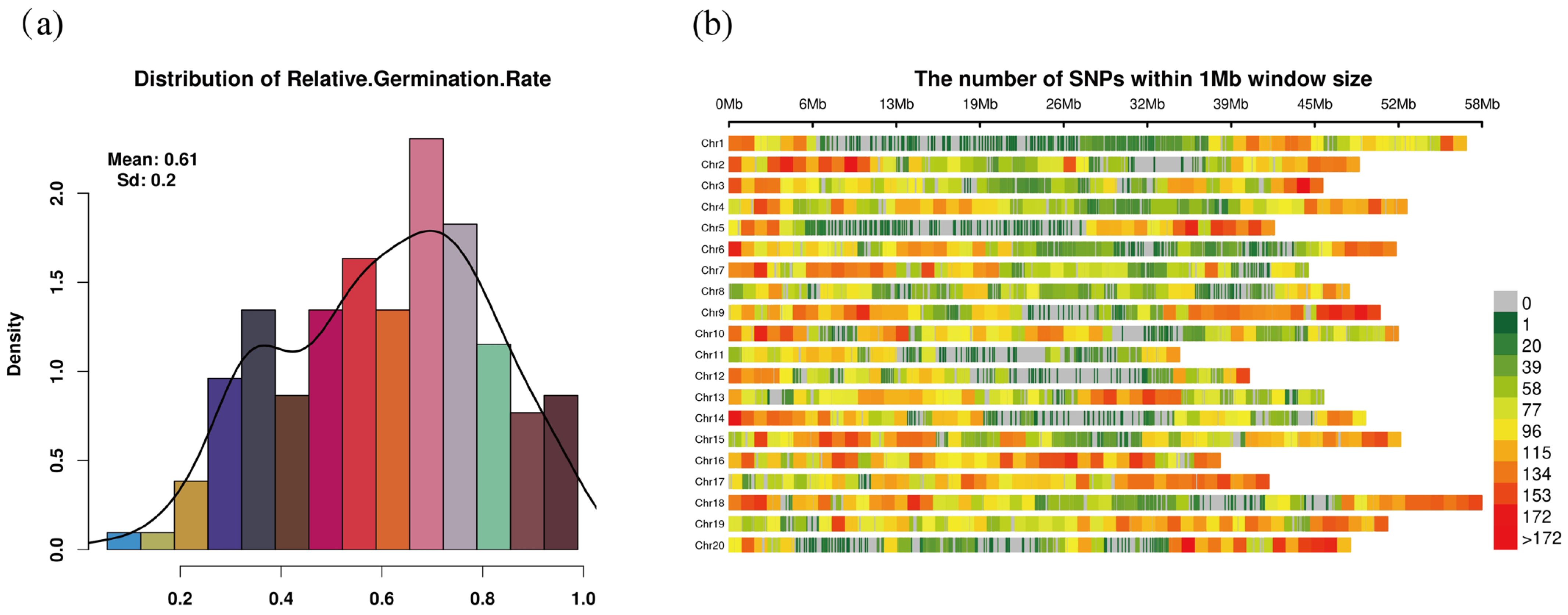

2.1. Phenotypic and SNP Distribution

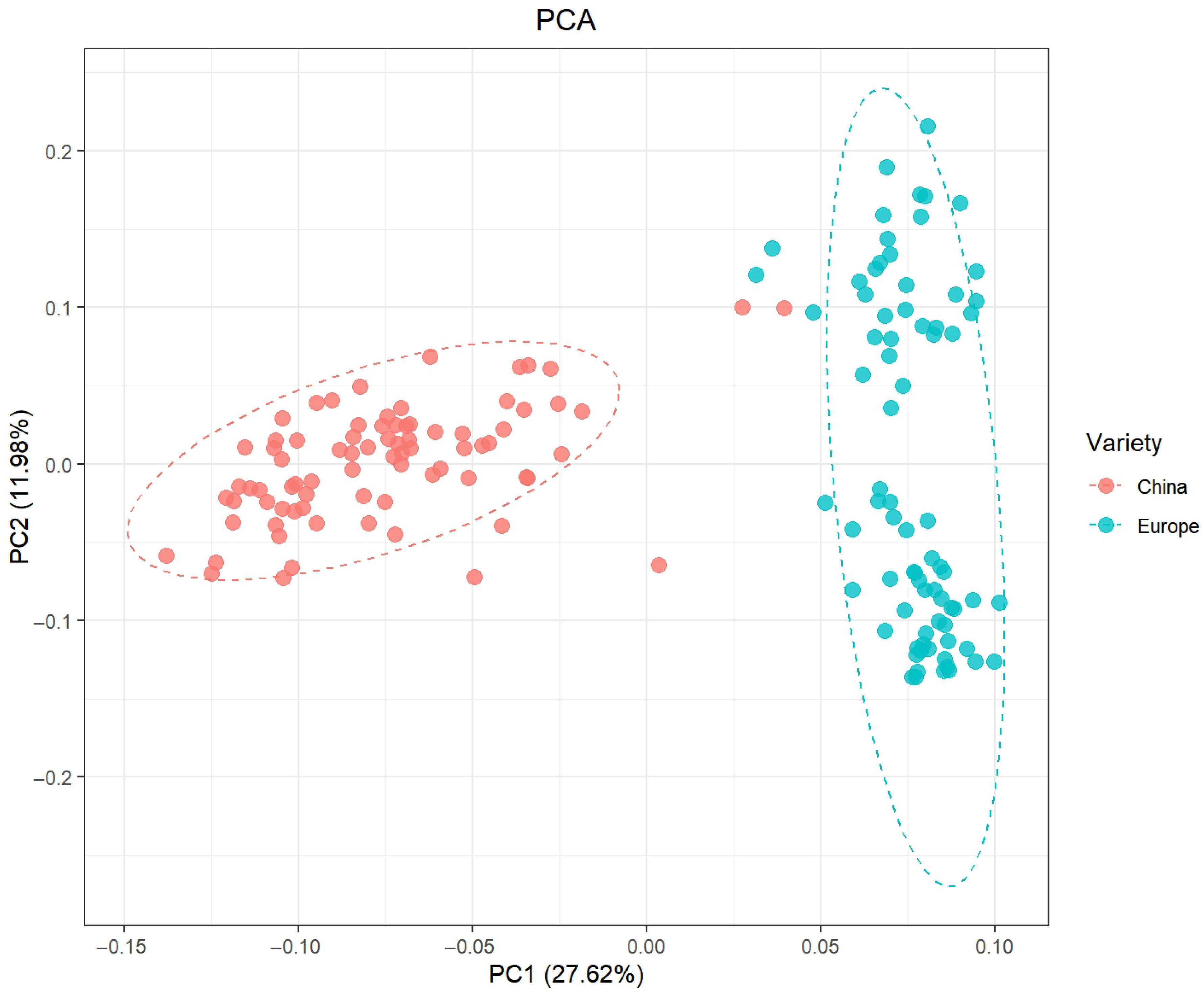

2.2. PCA Results

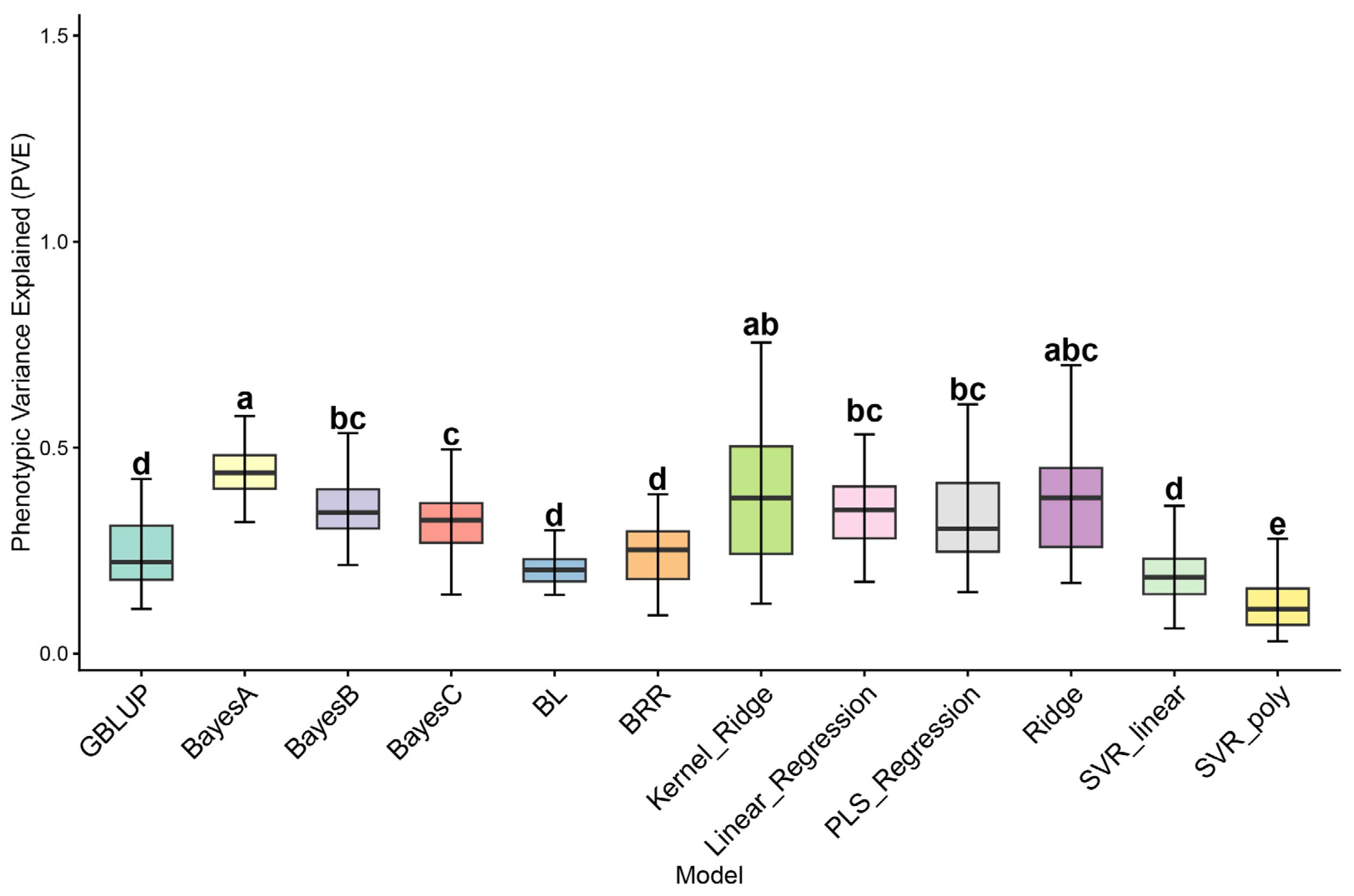

2.3. PVE Calculation Results

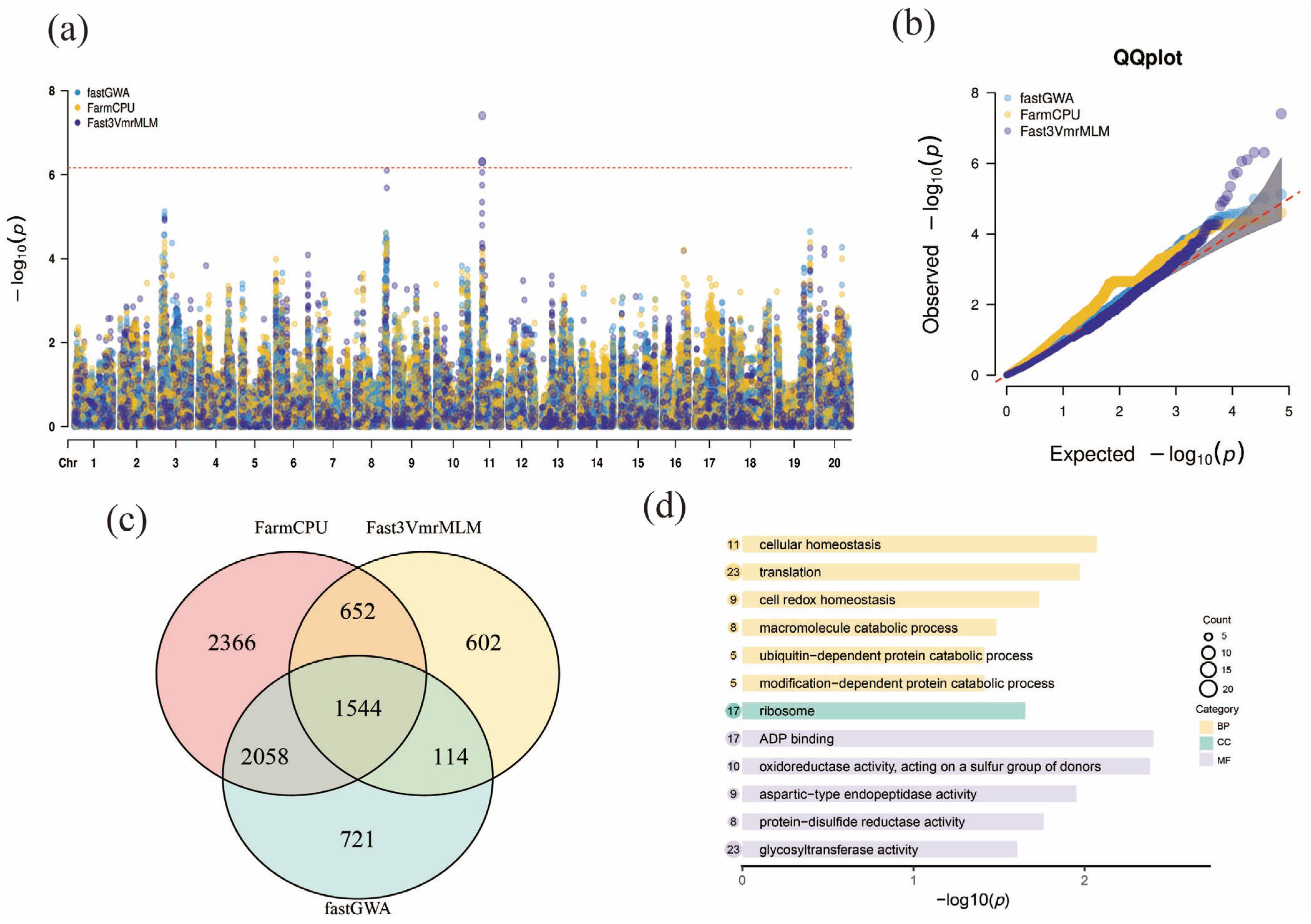

2.4. GWAS Analysis

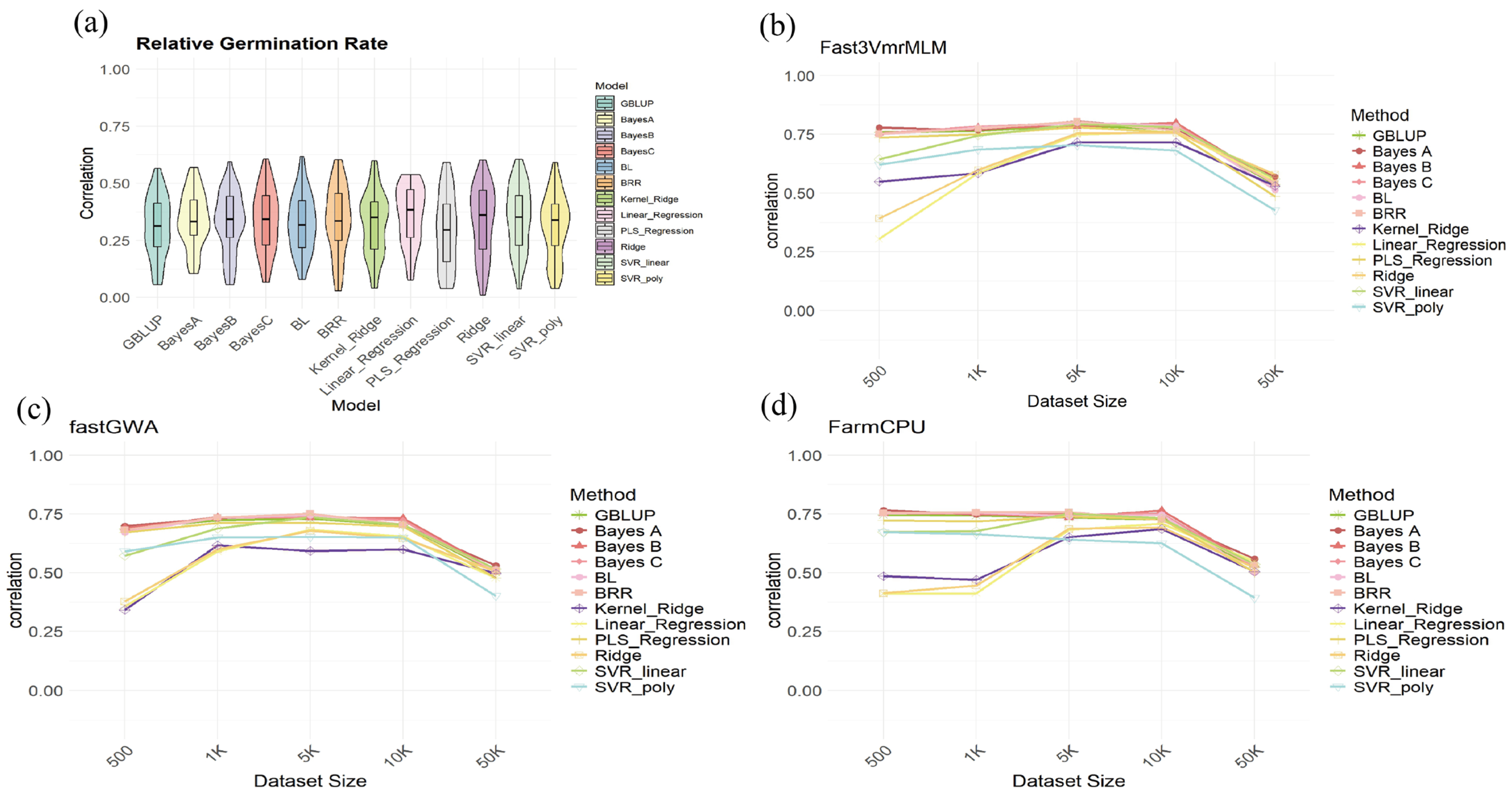

2.5. Joint GWAS-GS Analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. GWAS Results and Significant SNP Markers Associated with Cold Tolerance Traits

3.2. Analysis of PVE Differences

3.3. GWAS Selection Enhances GS Prediction Accuracy

3.4. Limitations of the Study and Future Prospects

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Phenotypic Data Collection

4.3. Genomic DNA Extraction and SNP Genotyping

4.4. Principal Component Analysis

4.5. PVE

4.6. GWAS Analysis and Candidate Gene Annotation

4.7. GWAS-GS

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Han, D.; Yang, Q.; Li, C.; Shi, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, C.; Qiu, L.; Jia, H.; et al. Cold tolerance SNPs and candidate gene mining in the soybean germination stage based on genome-wide association analysis. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Jiafeng, J.; Jiangang, L.; Minchong, S.; Xin, H.; Hanliang, S.; Yuanhua, D. Effects of cold plasma treatment on seed germination and seedling growth of soybean. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsegaw, M.; Zegeye, W.A.; Jiang, B.; Sun, S.; Yuan, S.; Han, T.; Wu, T. Progress and prospects of the molecular basis of soybean cold tolerance. Plants 2023, 12, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staniak, M.; Czopek, K.; Stępień-Warda, A.; Kocira, A.; Przybyś, M. Cold stress during flowering alters plant structure, yield and seed quality of different soybean genotypes. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appuhamilage, N.; Anuththara, S. Cold Temperature and Water Effect on Germination and Emergence of Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]; OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. Master’s Thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; Sun, R.; Xu, J.; Yan, X.; Jia, H.; Chai, S.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Sun, B.; Lu, W.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of Soybean Germplasm Resources Collected from China and Europe Under Cold Conditions. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2022, 23, 1383–1392. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.A.; Li, S.; Gao, H.; Feng, C.; Sun, P.; Sui, X.; Jing, Y.; Xu, K.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Comparative analysis of physiological variations and genetic architecture for cold stress response in soybean germplasm. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1095335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Li, M.; Yang, T.; Li, H.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Ma, M. Effect of cold plasma on physical-biochemical properties and nutritional components of soybean sprouts. Food Res. Int. 2022, 161, 111766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, R.; Sonah, H.; Patil, G.; Chen, W.; Prince, S.; Mutava, R.; Vuong, T.; Valliyodan, B.; Nguyen, H.T. Integrating omic approaches for abiotic stress tolerance in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, T.H.E.; Hayes, B.J.; Goddard, M.E. Prediction of Total Genetic Value Using Genome-Wide Dense Marker Maps. Genetics 2001, 157, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Cai, N.; Pacheco, P.P.; Narrandes, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, W. Applications of Support Vector Machine (SVM) Learning in Cancer Genomics. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2018, 15, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Alakus, C.; Larocque, D.; Labbe, A. Covariance regression with random forests. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T.; Rousseau, A.J.; Geubbelmans, M.; Burzykowski, T.; Valkenborg, D. Decision trees and random forests. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2023, 164, 894–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Zeng, X.; Xu, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, F.; He, F.; Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Gao, T.; Long, R. The whole-genome dissection of root system architecture provides new insights for the genetic improvement of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Shu, G.; Zhao, M.; Zheng, A.; Chang, X.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.-M. Fast3VmrMLM: A fast algorithm that integrates genome-wide scanning with machine learning to accelerate gene mining and breeding by design for polygenic traits in large-scale GWAS datasets. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 7101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dong, H.-B.; Peng, C.-J.; Du, X.-J.; Li, C.-X.; Han, X.-L.; Sun, W.-X.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Hu, L. Phenotypic plasticity of flowering time and plant height related traits in wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Luo, J. Metabolic GWAS-based dissection of genetic bases underlying the diversity of plant metabolism. Plant J. 2019, 97, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, J. GWAS. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, R265–R266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelett, D.J.; Conti, D.V.; Han, Y.; Al Olama, A.A.; Easton, D.; Eeles, R.A.; Kote-Jarai, Z.; Haiman, C.A.; Coetzee, G.A. Reducing GWAS Complexity. Cell Cycle 2016, 15, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, B. Overview of Statistical Methods for Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS). Methods Mol. Biol. 2013, 1019, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ishigaki, K. Beyond GWAS: From simple associations to functional insights. Semin. Immunopathol. 2022, 44, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marees, A.T.; de Kluiver, H.; Stringer, S.; Vorspan, F.; Curis, E.; Marie-Claire, C.; Derks, E.M. A tutorial on conducting genome-wide association studies: Quality control and statistical analysis. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 27, e1608. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chong, K.; Xu, Y. Chilling tolerance in rice: Past and present. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 268, 153576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Dong, X.; Cao, X.; Xu, C.; Wei, J.; Zhen, G.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Fang, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. QTL mapping for cold tolerance and higher overwintering survival rate in winter rapeseed (Brassica napus). J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 275, 153735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, W.; Xu, Y.; Cao, J.; Guo, X.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liang, G.; et al. COLD6-OSM1 module senses chilling for cold tolerance via 2′,3′-cAMP signaling in rice. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 4224–4238.e4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.H.; Nong, B.X.; Chen, L.; Yang, X.H.; Xia, X.Z.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Qing, D.J.; Gao, J.; Huang, C.C.; Li, D.T.; et al. QTL mapping and identification of candidate genes for cold tolerance at the germination stage in wild rice. Genes Genom. 2023, 45, 867–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-L.; Yu, S.; Yu, J.; Yu, L.; Zhou, S.-L. A modified CTAB protocol for plant DNA extraction. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2013, 48, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Zwickl, D.J.; Beerli, P.; Holder, M.T.; Lewis, P.O.; Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F.; Swofford, D.L.; Cummings, M.P. BEAGLE: An application programming interface and high-performance computing library for statistical phylogenetics. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; De Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, P.; de Los Campos, G. Genome-wide regression and prediction with the BGLR statistical package. Genetics 2014, 198, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Ho, T.K. Machine learning made easy: A review of scikit-learn package in python programming language. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 2019, 44, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Z.; Xu, J.; Yin, D.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, S.; Li, X. rMVP: A memory-efficient, visualization-enhanced, and parallel-accelerated tool for genome-wide association study. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2021, 19, 619–628. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Lee, S.H.; Goddard, M.E.; Visscher, P.M. GCTA: A tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am. J. Human Genet. 2011, 88, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L. CMplot: Circle manhattan plot. R Package Version 2020, 3, 699. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

| Chr | Start | End | Gene_Name | Snp_Pos | Gwas_Marker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gm03 | 6679636 | 6694991 | Glyma.03G052151 | 6685414 | Gm03_6685414 |

| Gm08 | 46134008 | 46143597 | Glyma.08G318000 | 46144933 | Gm08_46144933 |

| Gm11 | 6634544 | 6638369 | Glyma.11G087900 | 6634392 | Gm11_6634392 |

| Gm11 | 6685236 | 6691789 | Glyma.11G088400 | 6686188 | Gm11_6686188 |

| Gm11 | 6706992 | 6712243 | Glyma.11G088600 | 6707427 | Gm11_6707427 |

| Gm11 | 6766509 | 6768581 | Glyma.11G089200 | 6768477 | Gm11_6768477 |

| Gm11 | 6790735 | 6795318 | Glyma.11G089500 | 6791972 | Gm11_6791972 |

| Gm11 | 6824997 | 6831218 | Glyma.11G090100 | 6832069 | Gm11_6832069 |

| Gm11 | 6852742 | 6856435 | Glyma.11G090200 | 6857935 | Gm11_6857935 |

| Gm11 | 6885814 | 6891986 | Glyma.11G090900 | 6888005 | Gm11_6888005 |

| Gm15 | 17240737 | 17244374 | Glyma.15G179300 | 17239798 | Gm15_17239798 |

| Gm19 | 48536543 | 48545780 | Glyma.19G196700 | 48542345 | Gm19_48542345 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xue, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, R.; Yao, Y.; Cao, D.; He, W.; Liu, Q.; Luan, X.; Shu, Y.; et al. Integrating Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) and Marker-Assisted Selection for Enhanced Predictive Performance of Soybean Cold Tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010165

Xue Y, Tang X, Zhu X, Zhang R, Yao Y, Cao D, He W, Liu Q, Luan X, Shu Y, et al. Integrating Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) and Marker-Assisted Selection for Enhanced Predictive Performance of Soybean Cold Tolerance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010165

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Yongguo, Xiaofei Tang, Xiaoyue Zhu, Ruixin Zhang, Yubo Yao, Dan Cao, Wenjin He, Qi Liu, Xiaoyan Luan, Yongjun Shu, and et al. 2026. "Integrating Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) and Marker-Assisted Selection for Enhanced Predictive Performance of Soybean Cold Tolerance" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010165

APA StyleXue, Y., Tang, X., Zhu, X., Zhang, R., Yao, Y., Cao, D., He, W., Liu, Q., Luan, X., Shu, Y., & Liu, X. (2026). Integrating Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) and Marker-Assisted Selection for Enhanced Predictive Performance of Soybean Cold Tolerance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010165