Low Levels of Mouse γδ T Cell Development Persist in the Presence of Null Mutants of the LAT Adaptor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. LatNIL KI Mouse Generation

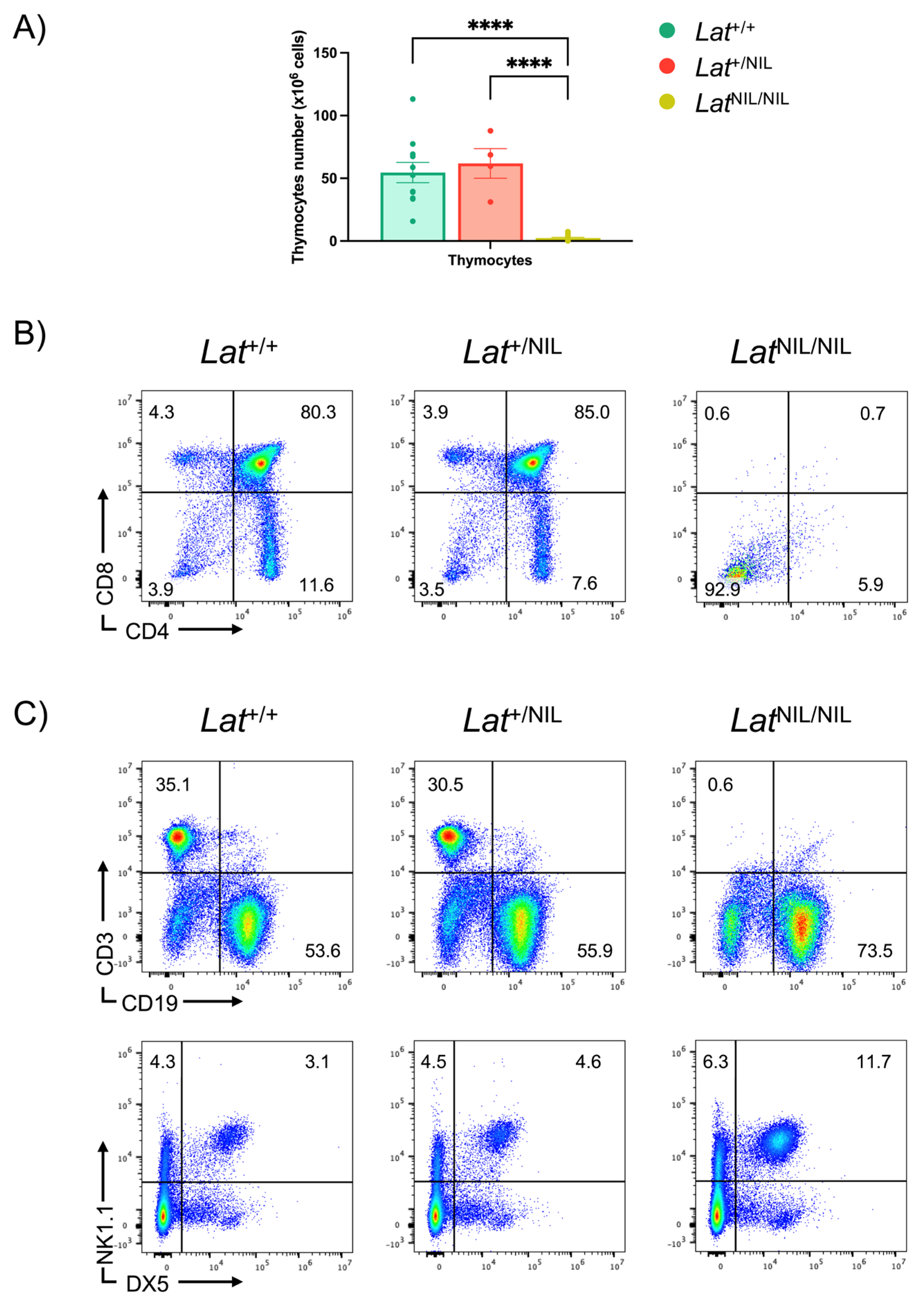

2.2. Thymic Development Arrest in LatNIL Mutant Mice

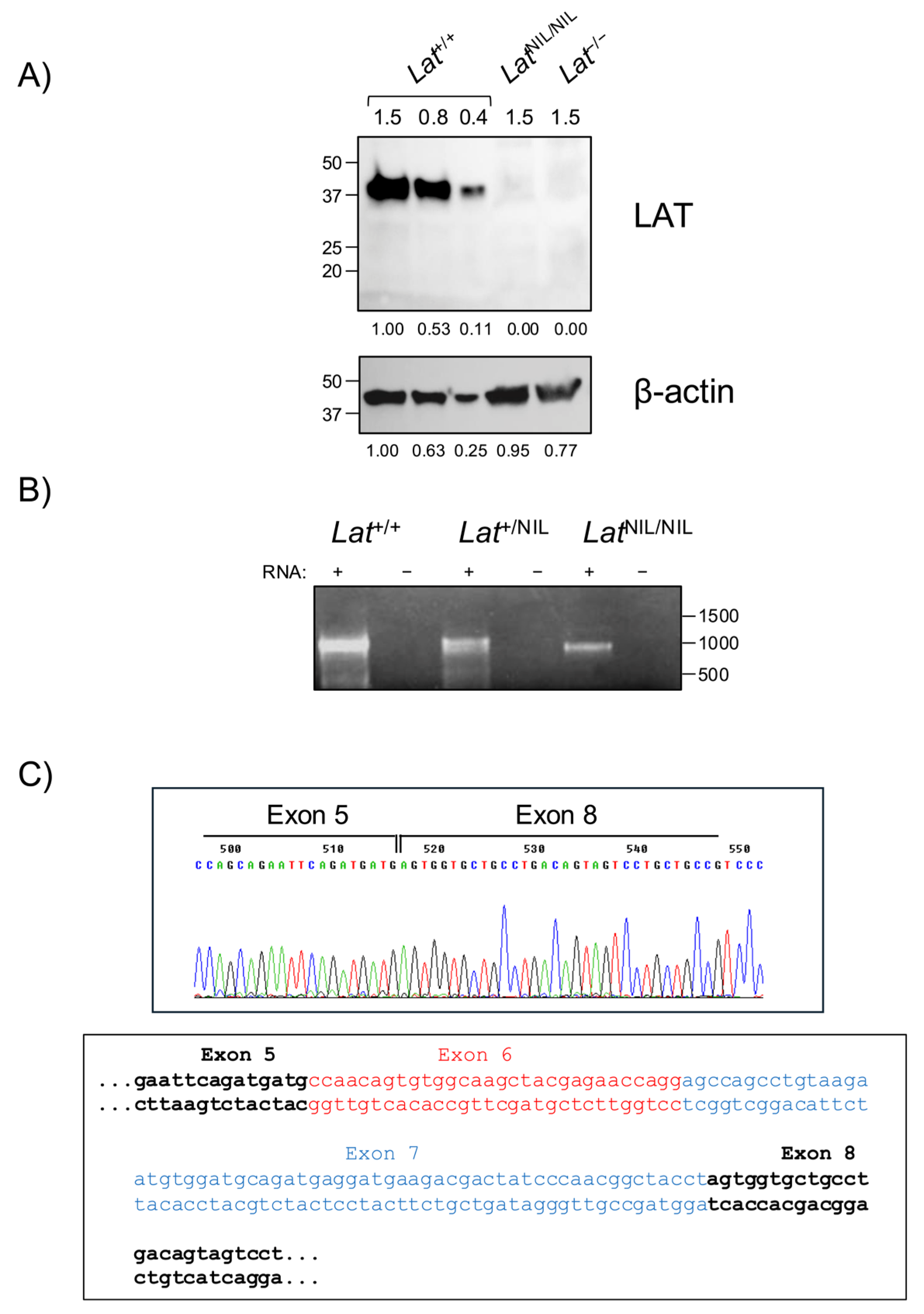

2.3. The LatNIL Mutation Generates an Alternative Splicing Event That Excludes Exons 6 and 7

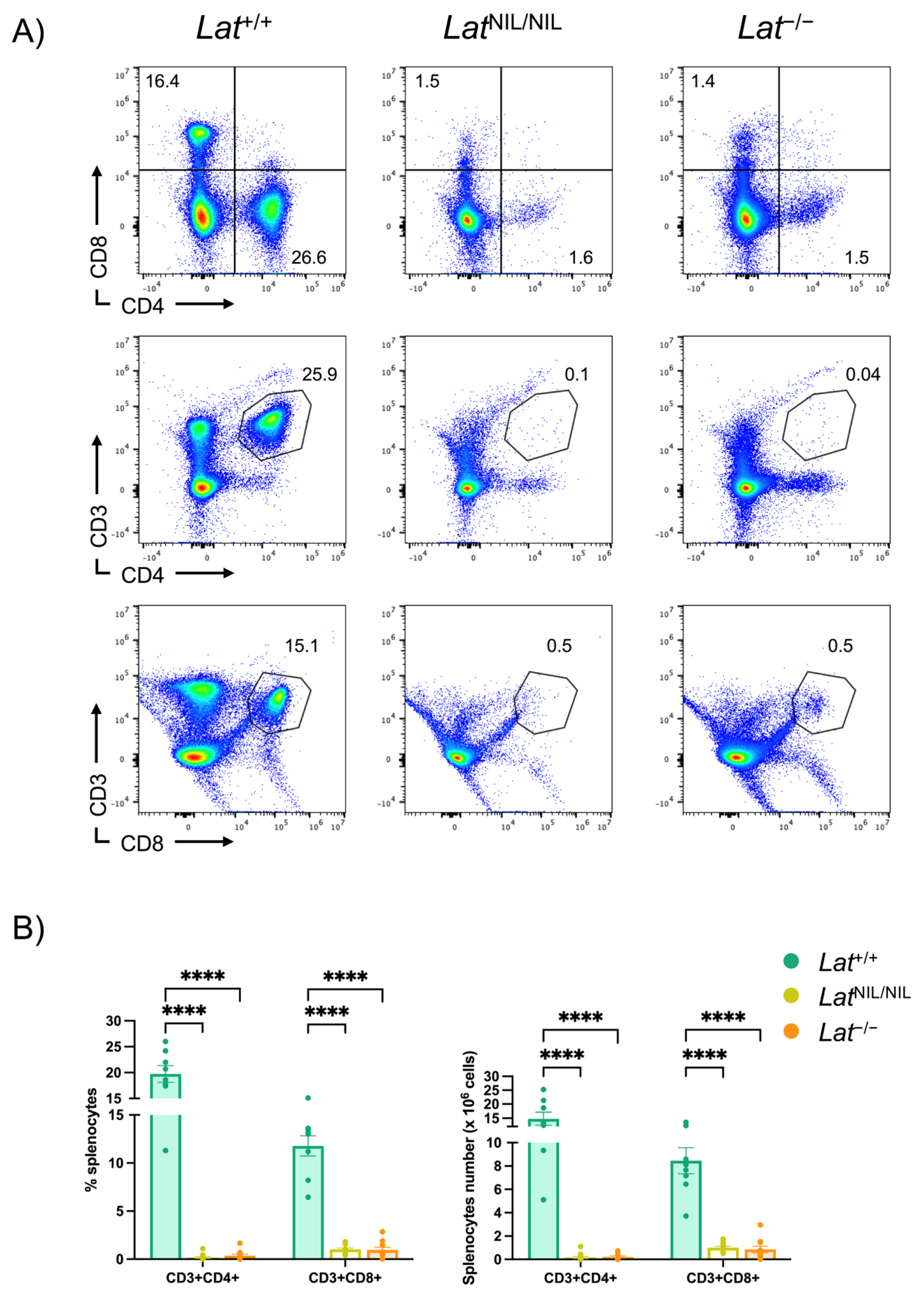

2.4. Marked Reduction in T Lymphocytes in Peripheral Lymphoid Organs of Homozygous LatNIL/NIL Mice

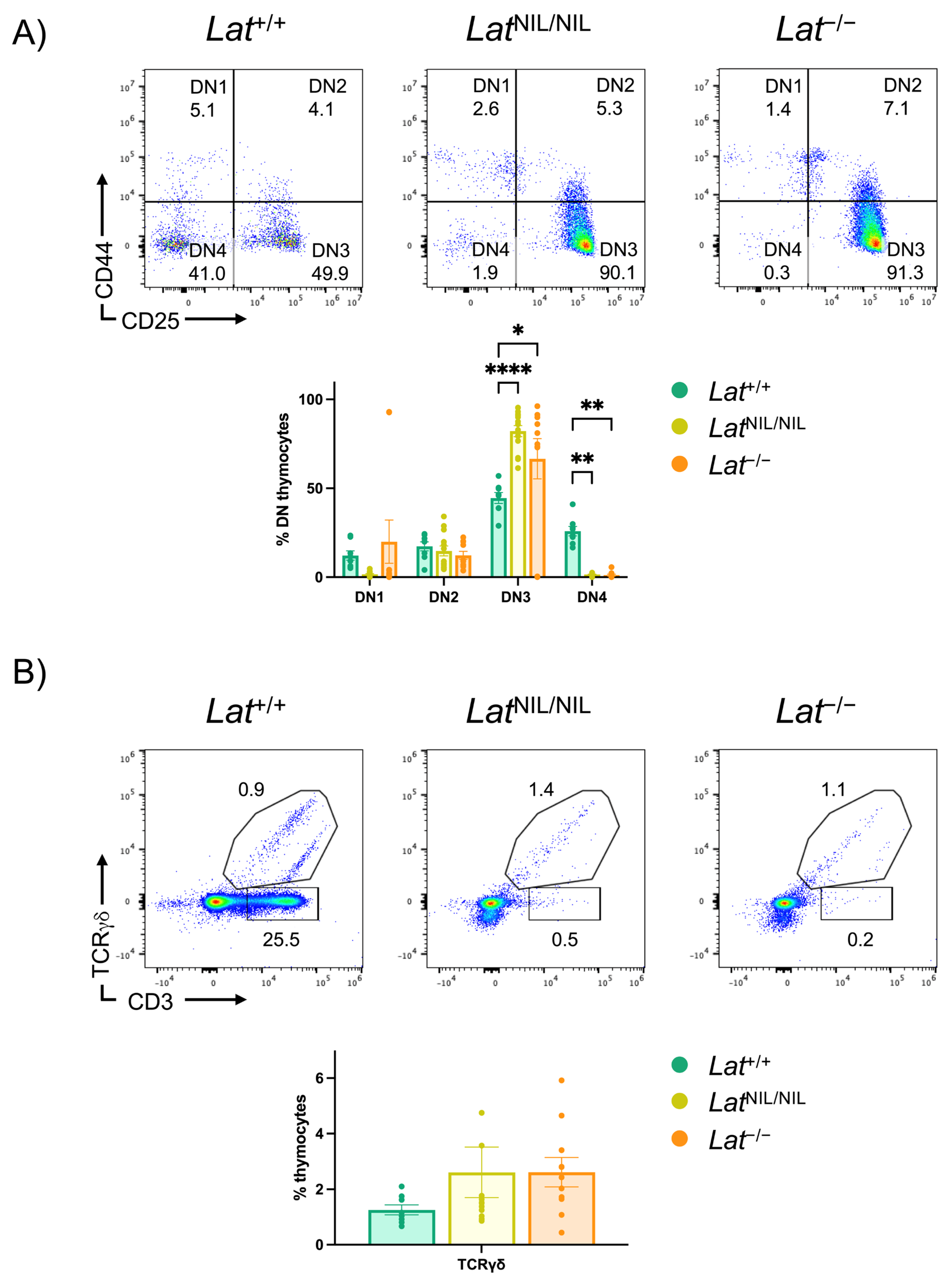

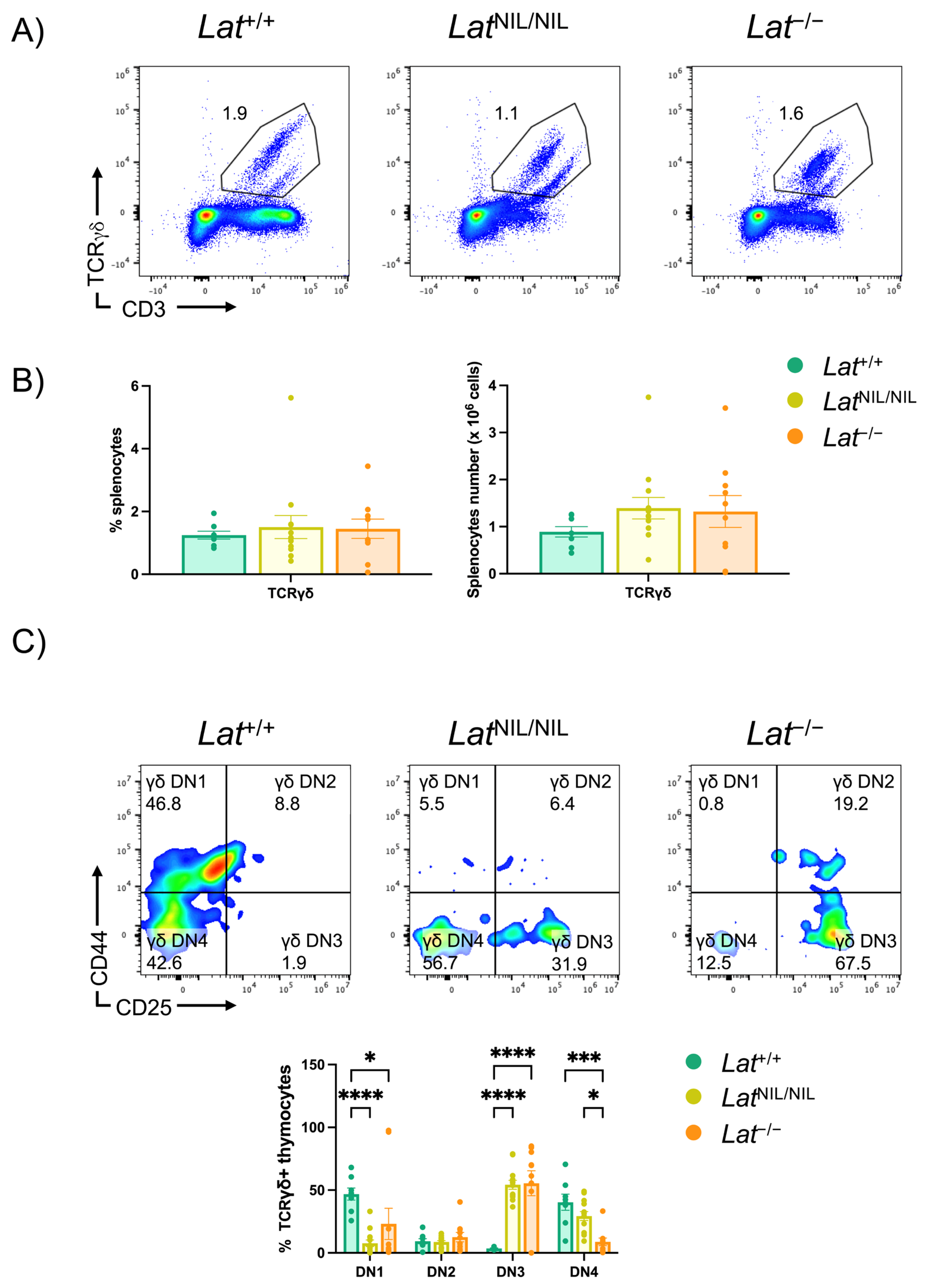

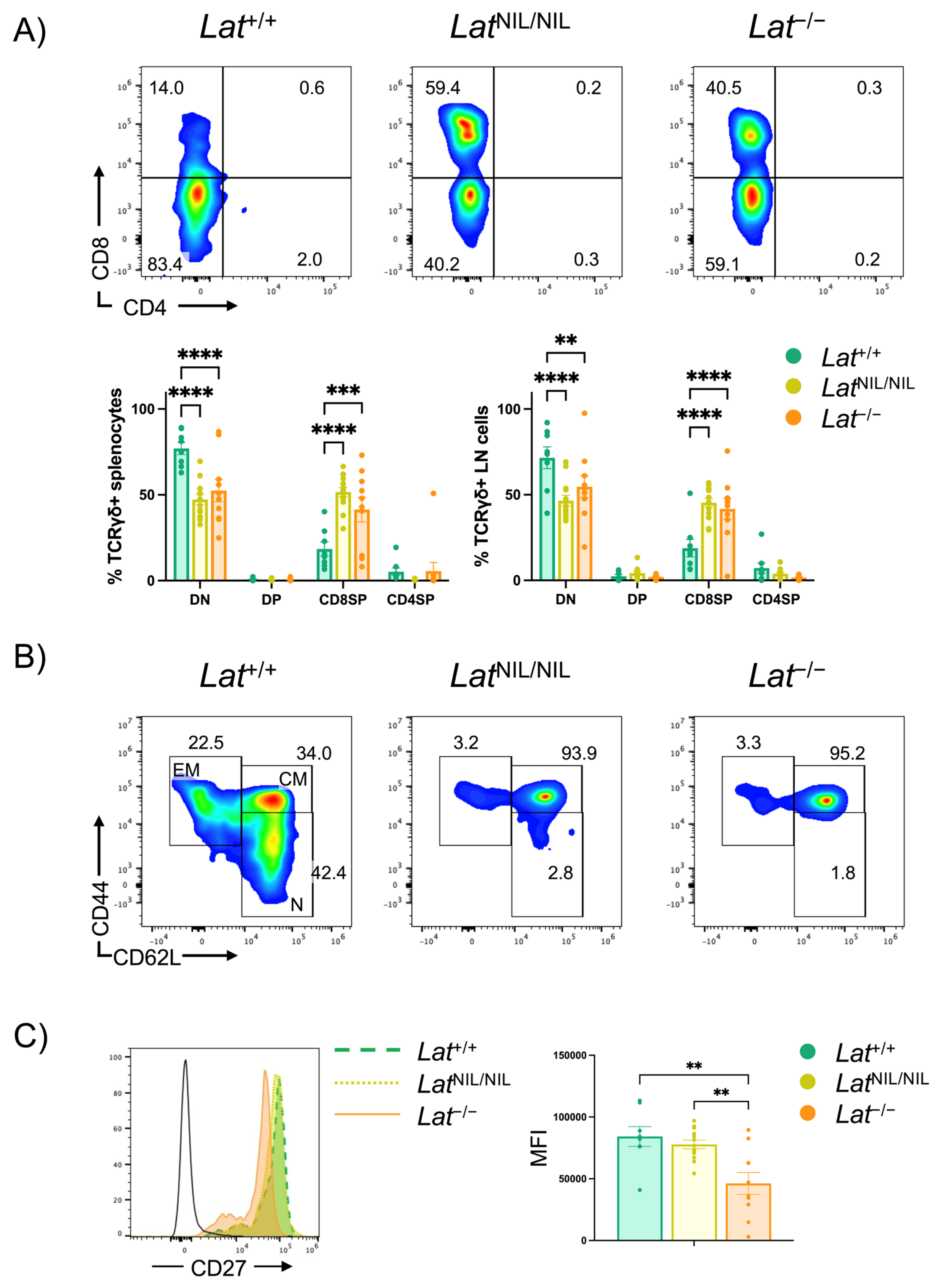

2.5. Effects of the LatNIL Mutation on γδ T Cells Development

2.6. Phenotype of γδ T Cells Found in LatNIL/NIL and Lat−/− Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Antibodies and Reagents

4.2. Animals

4.3. Generation of Knockin Mouse Expressing a LatNIL Allele

4.4. Preparation of Cell Lysates and Western Blotting

4.5. RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis and PCR

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Erk | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| Gads | Growth factor receptor-bound 2-related adaptor downstream of Shc |

| Grb2 | Growth factor receptor-bound 2 |

| LAT | Linker for the Activation of T cells |

| PLC-γ1 | Phospholipase C-γ1 |

| TCR | T Cell Receptor |

References

- Zhang, W.; Sloan-Lancaster, J.; Kitchen, J.; Trible, R.P.; Samelson, L.E. LAT: The ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase substrate that links T cell receptor to cellular activation. Cell 1998, 92, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, A.K.; Weiss, A. Insights into the initiation of TCR signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2014, 15, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtney, A.H.; Lo, W.L.; Weiss, A. TCR Signaling: Mechanisms of Initiation and Propagation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2018, 43, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, P.E.; Hatzihristidis, T.; Bryant, J.; Gaud, G. Early events in TCR signaling—The evolving role of ITAMs. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1563049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malissen, B.; Aguado, E.; Malissen, M. Role of the LAT adaptor in T-cell development and Th2 differentiation. Adv. Immunol. 2005, 87, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Burbach, B.J.; Medeiros, R.B.; Mueller, K.L.; Shimizu, Y. T-cell receptor signaling to integrins. Immunol. Rev. 2007, 218, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Trible, R.P.; Zhu, M.; Liu, S.K.; McGlade, C.J.; Samelson, L.E. Association of Grb2, Gads, and phospholipase C-gamma 1 with phosphorylated LAT tyrosine residues. Effect of LAT tyrosine mutations on T cell angigen receptor-mediated signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 23355–23361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Weiss, A. Identification of the minimal tyrosine residues required for linker for activation of T cell function. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 29588–29595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sommers, C.L.; Burshtyn, D.N.; Stebbins, C.C.; DeJarnette, J.B.; Trible, R.P.; Grinberg, A.; Tsay, H.C.; Jacobs, H.M.; Kessler, C.M.; et al. Essential role of LAT in T cell development. Immunity 1999, 10, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez-Cruz, S.; Aguado, E.; Richelme, S.; Chetaille, B.; Mura, A.M.; Richelme, M.; Pouyet, L.; Jouvin-Marche, E.; Xerri, L.; Malissen, B.; et al. LAT regulates gammadelta T cell homeostasis and differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommers, C.L.; Menon, R.K.; Grinberg, A.; Zhang, W.; Samelson, L.E.; Love, P.E. Knock-in mutation of the distal four tyrosines of linker for activation of T cells blocks murine T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 194, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommers, C.L.; Samelson, L.E.; Love, P.E. LAT: A T lymphocyte adapter protein that couples the antigen receptor to downstream signaling pathways. Bioessays 2004, 26, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz, P.E.; Wang, S.; Clarke, H.; Lu, X.; Stokoe, D.; Abo, A. Mapping the Zap-70 phosphorylation sites on LAT (linker for activation of T cells) required for recruitment and activation of signalling proteins in T cells. Biochem. J. 2001, 356, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joachim, A.; Aussel, R.; Gelard, L.; Zhang, F.; Mori, D.; Gregoire, C.; Villazala Merino, S.; Gaya, M.; Liang, Y.; Malissen, M.; et al. Defective LAT signalosome pathology in mice mimics human IgG4-related disease at single-cell level. J. Exp. Med. 2023, 220, e20231028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabouridis, P.S. Selective interaction of LAT (linker of activated T cells) with the open-active form of Lck in lipid rafts reveals a new mechanism for the regulation of Lck in T cells. Biochem. J. 2003, 371, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabouridis, P.S.; Isenberg, D.A.; Jury, E.C. A negatively charged domain of LAT mediates its interaction with the active form of Lck. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2011, 28, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chass, G.A.; Lovas, S.; Murphy, R.F.; Csizmadia, I.G. The role of enhanced aromatic π-electron donating aptitude of the tyrosyl sidechain with respect to that of phenylalanyl in intramolecular interactions. Eur. Phys. J. D 2002, 20, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulo-Echevarria, M.M.; Narbona-Sanchez, I.; Fernandez-Ponce, C.M.; Vico-Barranco, I.; Rueda-Ygueravide, M.D.; Dustin, M.L.; Miazek, A.; Duran-Ruiz, M.C.; Garcia-Cozar, F.; Aguado, E. A Stretch of Negatively Charged Amino Acids of Linker for Activation of T-Cell Adaptor Has a Dual Role in T-Cell Antigen Receptor Intracellular Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.-L.; Shah, N.H.; Ahsan, N.; Horkova, V.; Stepanek, O.; Salomon, A.R.; Kuriyan, J.; Weiss, A. Lck promotes Zap70-dependent LAT phosphorylation by bridging Zap70 to LAT. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.H.; Wang, Q.; Yan, Q.; Karandur, D.; Kadlecek, T.A.; Fallahee, I.R.; Russ, W.P.; Ranganathan, R.; Weiss, A.; Kuriyan, J. An electrostatic selection mechanism controls sequential kinase signaling downstream of the T cell receptor. eLife 2016, 5, e20105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klossowicz, M.; Marek-Bukowiec, K.; Arbulo-Echevarria, M.M.; Scirka, B.; Majkowski, M.; Sikorski, A.F.; Aguado, E.; Miazek, A. Identification of functional, short-lived isoform of linker for activation of T cells (LAT). Genes Immun. 2014, 15, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.P.; Finlay, D.K.; Hinton, H.J.; Clarke, R.G.; Fiorini, E.; Radtke, F.; Cantrell, D.A. Notch-induced T cell development requires phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 3441–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaramuzzino, S.; Potier, D.; Ordioni, R.; Grenot, P.; Payet-Bornet, D.; Luche, H.; Malissen, B. Single-cell transcriptomics uncovers an instructive T-cell receptor role in adult gammadelta T-cell lineage commitment. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e110023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prinz, I.; Meyer, A. What We Know and What We Don’t Know About the Function of gammadelta T Cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2025, 55, e70058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.C.; deBarros, A.; Pang, D.J.; Neves, J.F.; Peperzak, V.; Roberts, S.J.; Girardi, M.; Borst, J.; Hayday, A.C.; Pennington, D.J.; et al. CD27 is a thymic determinant of the balance between interferon-gamma- and interleukin 17-producing gammadelta T cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balagopalan, L.; Kortum, R.L.; Coussens, N.P.; Barr, V.A.; Samelson, L.E. The linker for activation of T cells (LAT) signaling hub: From signaling complexes to microclusters. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 26422–26429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.L.; Weiss, A. Adapting T Cell Receptor Ligand Discrimination Capability via LAT. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 673196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samelson, L.E. Signal transduction mediated by the T cell antigen receptor: The role of adapter proteins. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 20, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.L.; Shah, N.H.; Rubin, S.A.; Zhang, W.; Horkova, V.; Fallahee, I.R.; Stepanek, O.; Zon, L.I.; Kuriyan, J.; Weiss, A. Slow phosphorylation of a tyrosine residue in LAT optimizes T cell ligand discrimination. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbulo-Echevarria, M.M.; Vico-Barranco, I.; Zhang, F.; Fernandez-Aguilar, L.M.; Chotomska, M.; Narbona-Sanchez, I.; Zhang, L.; Malissen, B.; Liang, Y.; Aguado, E. Mutation of the glycine residue preceding the sixth tyrosine of the LAT adaptor severely alters T cell development and activation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1054920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.L.; Kuhlmann, M.; Rizzuto, G.; Ekiz, H.A.; Kolawole, E.M.; Revelo, M.P.; Andargachew, R.; Li, Z.; Tsai, Y.L.; Marson, A.; et al. A single-amino acid substitution in the adaptor LAT accelerates TCR proofreading kinetics and alters T-cell selection, maintenance and function. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.H.; Lobel, M.; Weiss, A.; Kuriyan, J. Fine-tuning of substrate preferences of the Src-family kinase Lck revealed through a high-throughput specificity screen. eLife 2018, 7, e35190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Blesa, A.; Klossowicz, M.; Lopez-Osuna, C.; Martinez-Florensa, M.; Malissen, B.; Garcia-Cozar, F.J.; Miazek, A.; Aguado, E. The membrane adaptor LAT is proteolytically cleaved following Fas engagement in a tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent fashion. Biochem. J. 2013, 450, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Centurion, P.; Minana, B.; Valcarcel, J.; Lehner, B. Mutations primarily alter the inclusion of alternatively spliced exons. eLife 2020, 9, e59959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irimia, M.; Blencowe, B.J. Alternative splicing: Decoding an expansive regulatory layer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2012, 24, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaal, T.D.; Maniatis, T. Multiple distinct splicing enhancers in the protein-coding sequences of a constitutively spliced pre-mRNA. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999, 19, 261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Burge, C.B. Splicing regulation: From a parts list of regulatory elements to an integrated splicing code. RNA 2008, 14, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.J.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Chew, S.L.; Zhang, M.Q.; Krainer, A.R. An increased specificity score matrix for the prediction of SF2/ASF-specific exonic splicing enhancers. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 2490–2508. [Google Scholar]

- Du, K.; Peng, Y.; Greenbaum, L.E.; Haber, B.A.; Taub, R. HRS/SRp40-mediated inclusion of the fibronectin EIIIB exon, a possible cause of increased EIIIB expression in proliferating liver. Mol. Cell Biol. 1997, 17, 4096–4104. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Li, J.Y.; Ge, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, G.P. Par-4/THAP1 complex and Notch3 competitively regulated pre-mRNA splicing of CCAR1 and affected inversely the survival of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Oncogene 2013, 32, 5602–5613. [Google Scholar]

- Buratti, E.; Stuani, C.; De Prato, G.; Baralle, F.E. SR protein-mediated inhibition of CFTR exon 9 inclusion: Molecular characterization of the intronic splicing silencer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 4359–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miazek, A.; Macha, K.; Laszkiewicz, A.; Kissenpfennig, A.; Malissen, B.; Kisielow, P. Peripheral Thy1+ lymphocytes rearranging TCR-gammadelta genes in LAT-deficient mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 2596–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balagopalan, L.; Ashwell, B.A.; Bernot, K.M.; Akpan, I.O.; Quasba, N.; Barr, V.A.; Samelson, L.E. Enhanced T-cell signaling in cells bearing linker for activation of T-cell (LAT) molecules resistant to ubiquitylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2885–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Ohtsuka, K.; Watanabe, H.; Asakura, H.; Abo, T. Detailed characterization of gamma delta T cells within the organs in mice: Classification into three groups. Immunology 1993, 80, 380–387. [Google Scholar]

- French, J.D.; Roark, C.L.; Born, W.K.; O’Brien, R.L. Gammadelta T lymphocyte homeostasis is negatively regulated by beta2-microglobulin. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 1892–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmolka, N.; Wencker, M.; Hayday, A.C.; Silva-Santos, B. Epigenetic and transcriptional regulation of gammadelta T cell differentiation: Programming cells for responses in time and space. Semin. Immunol. 2015, 27, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Ruiz, M.; Ribot, J.C.; Grosso, A.R.; Goncalves-Sousa, N.; Pamplona, A.; Pennington, D.J.; Regueiro, J.R.; Fernandez-Malave, E.; Silva-Santos, B. TCR signal strength controls thymic differentiation of discrete proinflammatory gammadelta T cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arbulo-Echevarria, M.M.; Fernandez-Aguilar, L.M.; Kurz, E.; Vico-Barranco, I.; Muñoz-Fernández, R.; Narbona-Sánchez, I.; Carrasco, M.; Malissen, B.; Dustin, M.L.; Aguado, E. Low Levels of Mouse γδ T Cell Development Persist in the Presence of Null Mutants of the LAT Adaptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12186. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412186

Arbulo-Echevarria MM, Fernandez-Aguilar LM, Kurz E, Vico-Barranco I, Muñoz-Fernández R, Narbona-Sánchez I, Carrasco M, Malissen B, Dustin ML, Aguado E. Low Levels of Mouse γδ T Cell Development Persist in the Presence of Null Mutants of the LAT Adaptor. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12186. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412186

Chicago/Turabian StyleArbulo-Echevarria, Mikel M., Luis M. Fernandez-Aguilar, Elke Kurz, Inmaculada Vico-Barranco, Raquel Muñoz-Fernández, Isaac Narbona-Sánchez, Manuel Carrasco, Bernard Malissen, Michael L. Dustin, and Enrique Aguado. 2025. "Low Levels of Mouse γδ T Cell Development Persist in the Presence of Null Mutants of the LAT Adaptor" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12186. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412186

APA StyleArbulo-Echevarria, M. M., Fernandez-Aguilar, L. M., Kurz, E., Vico-Barranco, I., Muñoz-Fernández, R., Narbona-Sánchez, I., Carrasco, M., Malissen, B., Dustin, M. L., & Aguado, E. (2025). Low Levels of Mouse γδ T Cell Development Persist in the Presence of Null Mutants of the LAT Adaptor. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12186. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412186