The Importance of Humic Acids in Shaping the Resistance of Soil Microorganisms and the Tolerance of Zea mays to Excess Cadmium in Soil

Abstract

1. Introduction

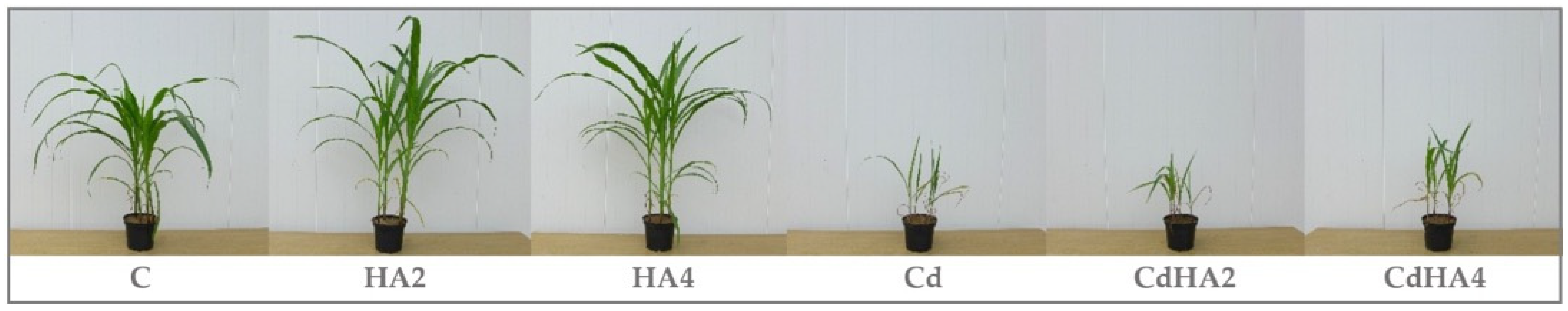

2. Results

2.1. Effect of Soil Contamination with Cadmium (Cd) on the Abundance and Diversity of Culturable Bacteria

2.2. Effect of Soil Contamination with Cadmium (Cd2+) on the Abundance and Diversity of Non-Culturable Bacteria

2.3. Metabolic and Ecological Functions of the Analyzed Bacteria

2.4. Effect of Soil Contamination with Cadmium on Zea mays Leaf Greenness Index (SPAD)

3. Discussion

3.1. Effect of Soil Contamination with Cadmium and Amendment with Humus Active on Culturable Bacteria

3.2. Effect of Soil Contamination with Cadmium and Amendment with Humus Active on the Abundance of Non-Culturable Bacteria

3.3. Effect of Cadmium and Humus Active on the Soil Microbiome, Bacterial Metabolic Functions, and the Biomass of Zea mays as Well as Leaf Greenness Index (SPAD)

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Characteristics of the Soil Material

4.2. Cadmium

4.3. Characteristics of Humus Active Soil Biostimulant

4.4. Experiment Design

4.5. Methodology of Chemical and Physicochemical Analyses of Soil

4.6. Methodology of Microbiological Analyses of Soil

4.7. Data Analysis and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Hou, D.; Jia, X.; Wang, L.; McGrath, S.P.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, F.-J.; Bank, M.S.; O’Connor, D.; Nriagu, J. Global Soil Pollution by Toxic Metals Threatens Agriculture and Human Health. Science 2025, 388, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubier, A.; Wilkin, R.T.; Pichler, T. Cadmium in Soils and Groundwater: A Review. Appl. Geochem. 2019, 108, 104388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group, W.R.B. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, Update 2015. International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps. In World Soil Resources Reports; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Status of the World’s Soil Resources|FAO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/family-farming/detail/en/c/357394/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Zou, C.; Shi, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, N. The Characteristics, Enrichment, and Migration Mechanism of Cadmium in Phosphate Rock and Phosphogypsum of the Qingping Phosphate Deposit, Southwest China. Minerals 2023, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Song, C.; Chen, Z.; Guan, H.; Xing, D.; Gao, T.; Sun, J.; Ning, Z.; Xiao, T. Geochemical Factors Controlling the Mobilization of Geogenic Cadmium in Soils Developed on Carbonate Bedrocks in Southwest China. Geoderma 2023, 437, 116606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yan, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Andom, O.; Li, Z. Microplastics Alter Cadmium Accumulation in Different Soil-Plant Systems: Revealing the Crucial Roles of Soil Bacteria and Metabolism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 474, 134768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S. Protective Role of the Essential Trace Elements in the Obviation of Cadmium Toxicity: Glimpses of Mechanisms. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2022, 200, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, T.; Wang, H.; Liang, Y.; Cui, K.; Yang, K.; Lu, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Gao, N.; Yu, Q.; et al. Source Tracing with Cadmium Isotope and Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Sediment of an Urban River, China. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 305, 119325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Wu, S.; Xie, H.; Chen, F.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, R. Effect of Phosphate on Cadmium Immobilized by Microbial-Induced Carbonate Precipitation: Mobilization or Immobilization? J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Dong, S.; Li, L.; Wang, S. Effects of Biochar and Magnesium Oxide on Cadmium Immobilized by Microbially Induced Carbonate: Mobilization or Immobilization in Alkaline Agricultural Soils? Environ. Pollut. 2024, 358, 124537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhong, L.; Dong, Y.; Wang, G.; Shi, K. Cd Immobilization Mechanisms in a Pseudomonas Strain and Its Application in Soil Cd Remediation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Q.; Chang, C.; Huang, F.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H. Sulfur-Driven Approaches to Cadmium Detoxification: From Soil Microbials to Plant-Based Mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 55, 1383–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.; Dai, J.; Jian, J.; Yan, C.; Peng, D.; Liu, H.; Xu, H. The Effect of Phosphate Solubilizing Bacteria on the Fate of Cadmium Immobilized by Microbial Induced Phosphate Precipitation. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 380, 125125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennaciri, Y.; Bettach, M. The Chemical Behavior of the Different Impurities Present in Phosphogypsum: A Review. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2024, 199, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samrane, K.; Bouhaouss, A. Cadmium in Phosphorous Fertilizers: Balance and Trends. Rasayan J. Chem. 2022, 15, 2103–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, I.; Afzal, S.; Ashraf, M.A.; Rasheed, R.; Saleem, M.H.; Alatawi, A.; Ameen, F.; Fahad, S. Effect of Metals or Trace Elements on Wheat Growth and Its Remediation in Contaminated Soil. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 2258–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Kaur, H.; Kaur, H.; Srivastava, S. The Beneficial Roles of Trace and Ultratrace Elements in Plants. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 100, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, S.; Mohapatra, B.; Gupta, A. Plant Growth-Promoting Microbe Mediated Uptake of Essential Nutrients (Fe, P, K) for Crop Stress Management: Microbe–Soil–Plant Continuum. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 689972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubeen, S.; Ni, W.; He, C.; Yang, Z. Agricultural Strategies to Reduce Cadmium Accumulation in Crops for Food Safety. Agriculture 2023, 13, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilachi, I.C.; Stoleru, V.; Gavrilescu, M. Analysis of Heavy Metal Impacts on Cereal Crop Growth and Development in Contaminated Soils. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Dong, W.; Luo, Y.; Fan, T.; Xiong, X.; Sun, L.; Hu, X. Cultivar Diversity and Organ Differences of Cadmium Accumulation in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Allow the Potential for Cd-Safe Staple Food Production on Contaminated Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 134534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, D.; Braissant, O. Cadmium-tolerant Bacteria: Current Trends and Applications in Agriculture. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 74, 311–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food, Agriculture; Food, Environmental Protection Section, FAO/IAEA Agriculture and Biotechnology Laboratory. Food and Environmental Protection Newsletter; Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Techniques in Food and Agriculture, Food and Environmental Protection Section: Vienna, Austria, 2018; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

- Drabesch, S.; Lechtenfeld, O.J.; Bibaj, E.; León Ninin, J.M.; Lezama Pachecco, J.; Fendorf, S.; Planer-Friedrich, B.; Kappler, A.; Muehe, E.M. Climate Induced Microbiome Alterations Increase Cadmium Bioavailability in Agricultural Soils with pH below 7. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Sun, L.; Tian, J.; Wu, N. Cadmium Pollution Impact on the Bacterial Community Structure of Arable Soil and the Isolation of the Cadmium Resistant Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 698834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.; Singh, D. Bioremediation Potential of Cadmium-Resistant Bacteria Isolated from Water Samples of Rivulet Holy Kali Bein, Punjab, India. Bioremediat. J. 2024, 28, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, S.; Chen, X.; Dong, Y.; Zeng, M.; Yan, C.; Hou, L.; Jiao, R. Isolation of Cadmium-Resistance and Siderophore-Producing Endophytic Bacteria and Their Potential Use for Soil Cadmium Remediation. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Li, Q.; Tian, Z.; He, Q.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Gu, Y.; Zou, L.; Zhao, K.; et al. Co-Application of Cadmium-Immobilizing Bacteria and Organic Fertilizers Alter the Wheat Root Soil Chemistry and Microbial Communities. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 287, 117288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Xiong, Y.; Li, G.; Cui, J.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, L. Effects of Dissolved Organic Matter on Distribution Characteristics of Heavy Metals and Their Interactions with Microorganisms in Soil under Long-Term Exogenous Effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 947, 174565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Hui, C.; Zhang, N.; Liu, L.; Li, H.; Zheng, H. Development of Cadmium Multiple-Signal Biosensing and Bioadsorption Systems Based on Artificial Cad Operons. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 585617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, N.; Xie, X.; Fan, Q. Cadmium Resistance, Microbial Biosorptive Performance and Mechanisms of a Novel Biocontrol Bacterium Paenibacillus sp. LYX-1. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 68692–68706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Sharma, S.; Paavan Gupta, M.; Goyal, S.; Talukder, D.; Akhtar, M.S.; Kumar, R.; Umar, A.; Alkhanjaf, A.A.M.; Baskoutas, S. Mechanisms of Microbial Resistance against Cadmium—A Review. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galan-Freyle, N.J.; Aranguren-Diaz, Y.; Ospina-Maldonado, S.L.; Chapuel-Aguillon, P.F.; Pertuz-Peña, M.F.; Hernandez-Rivera, S.P.; Pacheco-Londoño, L.C. Exploring Cadmium Bioaccumulation and Bioremediation Mechanisms and Related Genes in Soil Microorganisms: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 20215–20231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Huang, Q.; Cai, Y.; Xiao, L.; Wang, T.; Li, X.; Wu, W.; Yuan, G. A Comparative Assessment of Humic Acid and Biochar Altering Cadmium and Arsenic Fractions in a Paddy Soil. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Song, G.; Zheng, Z.; Mi, X.; Song, Z. Exploring the Impact of Fulvic Acid and Humic Acid on Heavy Metal Availability to Alfalfa in Molybdenum Contaminated Soil. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, E.; Ekinci, M.; Turan, M.; Ağar, G.; Dursun, A.; Kul, R.; Alim, Z.; Argin, S. Humic + Fulvic Acid Mitigated Cd Adverse Effects on Plant Growth, Physiology and Biochemical Properties of Garden Cress. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8040, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, C.A.; Yong, R.N. Humic Acid Preparation, Properties and Interactions with Metals Lead and Cadmium. Eng. Geol. 2006, 85, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangelou, M.W.H.; Daghan, H.; Schaeffer, A. The Influence of Humic Acids on the Phytoextraction of Cadmium from Soil. Chemosphere 2004, 57, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Luo, Z.; Yu, Y.; Liu, L.; Wu, B.; Liu, Q. Insight into Mineral-Microbe Interaction on Cadmium Immobilization via Microbially Induced Phosphate Precipitation with Various Phosphate Minerals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 498, 139854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Pi, B.; Dai, J.; Nie, Z.; Yu, G.; Du, W. Effects of Humic Acid on the Growth and Cadmium Accumulation of Maize (Zea mays L.) Seedlings. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2025, 27, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tibco Software Inc. Statistica, Version 13; Data Analysis Software System; Tibco Software Inc.: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.tibco.com/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Syed, A.; Zeyad, M.T.; Shahid, M.; Elgorban, A.M.; Alkhulaifi, M.M.; Ansari, I.A. Heavy Metals Induced Modulations in Growth, Physiology, Cellular Viability, and Biofilm Formation of an Identified Bacterial Isolate. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 25076–25088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Qin, L.; Sun, X.; Zhao, S.; Yu, L.; Wang, M.; Chen, S. Linking Bacterial Growth Responses to Soil Salinity with Cd Availability. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2022, 109, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, R.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Luo, L.; Wang, P.; Xia, H.; Zhou, Y. Ecotoxicological Impacts of Cadmium on Soil Microorganisms and Earthworms Eisenia Foetida: From Gene Regulation to Physiological Processes. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1479500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Fu, S.; Sarkodie, E.K.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, L.; Liang, Y.; Yin, H.; Bai, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; et al. Ecological Responses of Bacterial Assembly and Functions to Steep Cd Gradient in a Typical Cd-Contaminated Farmland Ecosystem. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 229, 113067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camillone, N.R.; Bruns, M.A.V.; Román, R.; Wasner, D.; Couradeau, E. Translationally Active Soil Microorganisms during Substrate-Induced Respiration. bioRxiv 2023, 2023.12.20.572626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, W.; Lu, X. Shifts in Bacterial Diversity, Interactions and Microbial Elemental Cycling Genes under Cadmium Contamination in Paddy Soil: Implications for Altered Ecological Function. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros-Lajszner, E.; Wyszkowska, J.; Borowik, A.; Kucharski, J. The Response of the Soil Microbiome to Contamination with Cadmium, Cobalt and Nickel in Soil Sown with Brassica Napus. Minerals 2021, 11, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campillo-Cora, C.; Rodríguez-Seijo, A.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Fernández-Calviño, D.; Santás-Miguel, V. Effect of Heavy Metal Pollution on Soil Microorganisms: Influence of Soil Physicochemical Properties. A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2025, 124, 103706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnholm, T.R.; Tisa, L.S. The Ins and Outs of Metal Homeostasis by the Root Nodule Actinobacterium Frankia. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Dolfing, J.; Guo, Z.; Chen, R.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.; Lin, X.; Feng, Y. Important Ecophysiological Roles of Non-Dominant Actinobacteria in Plant Residue Decomposition, Especially in Less Fertile Soils. Microbiome 2021, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, B.; Huo, L.; Cao, M.; Ke, Y.; Wang, L.; Tan, W.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, X. Insights into the Critical Roles of Water-Soluble Organic Matter and Humic Acid within Kitchen Compost in Influencing Cadmium Bioavailability. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborowska, M.; Kucharski, J.; Wyszkowska, J. Using Basalt Flour and Brown Algae to Improve Biological Properties of Soil Contaminated with Cadmium. Soil Water Res. 2015, 10, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Dang, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Bian, H.; Ivanets, A.; Zheng, J.; He, X.; García-Mina, J.M.; et al. Conversion Mechanism of Pyrolysis Humic Substances of Cotton Stalks and Carbide Slag and Its Excellent Repair Performance in Cd-Contaminated Soil. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 494, 153147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Paredes, A.; Valdés, G.; Araneda, N.; Valdebenito, E.; Hansen, F.; Nuti, M.; Aguilar-Paredes, A.; Valdés, G.; Araneda, N.; Valdebenito, E.; et al. Microbial Community in the Composting Process and Its Positive Impact on the Soil Biota in Sustainable Agriculture. Agronomy 2023, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszkowska, J.; Borowik, A.; Zaborowska, M.; Kucharski, J. Sensitivity of Zea Mays and Soil Microorganisms to the Toxic Effect of Chromium (VI). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowik, A.; Wyszkowska, J.; Zaborowska, M.; Kucharski, J. Regulation of the Microbiome in Soil Contaminated with Diesel Oil and Gasoline. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborowska, M.; Wyszkowska, J.; Słaba, M.; Borowik, A.; Kucharski, J.; Bernat, P. The Effect of Organic Materials on the Response of the Soil Microbiome to Bisphenol A. Molecules 2025, 30, 3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, A.; Drosos, M. The Essential Role of Humified Organic Matter in Preserving Soil Health. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X. The Properties of Microorganisms and Plants in Soils after Amelioration. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, D.; Misra, P.; Singh, S.; Kalra, A. Humic Acid Rich Vermicompost Promotes Plant Growth by Improving Microbial Community Structure of Soil as Well as Root Nodulation and Mycorrhizal Colonization in the Roots of Pisum Sativum. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2017, 110, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, J.; Jiang, C.; Wu, M.; Liu, M.; Li, Z. Distinct Successions of Common and Rare Bacteria in Soil Under Humic Acid Amendment—A Microcosm Study. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Gao, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zuo, H.; Wei, Z. Roles of Different Humin and Heavy-Metal Resistant Bacteria from Composting on Heavy Metal Removal. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 296, 122375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Li, Z.; Zhou, L.; Xie, J.; Zhou, Q.; Ding, M.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Nie, M.; Huang, G. Rhizosphere Microbiota Modulate Cadmium Mobility Dynamics and Phytotoxicity in Rice under Differential Cd Stress. Plant Soil 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhou, J.; Xu, X.; Na, M.; Xu, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zheng, X. Inoculation of Cadmium-Tolerant Bacteria to Regulate Microbial Activity and Key Bacterial Population in Cadmium-Contaminated Soils during Bioremediation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 271, 115957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Shao, C.; Jin, Q.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, H.; Lei, H.; Qian, J.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Cadmium Contamination on Bacterial and Fungal Communities in Panax Ginseng-Growing Soil. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Yu, L.; Sun, X.; Qin, L.; Liu, J.; Han, Y.; Chen, S. Integrating Rhizosphere Bacterial Structure and Metabolites with Soil Cd Availability in Different Parent Paddy Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 177096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; He, Q.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Liu, H.; Mu, Q.; Wang, S.; Nie, J.; Lin, S.; He, Q.; et al. Effects of Cadmium Stress on Root Exudates and Soil Rhizosphere Microorganisms of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) and Its Ecological Regulatory Mechanisms. Plants 2025, 14, 1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.; Saha, J.; Dutta, P.; Pal, A. Bacterial Homeostasis and Tolerance to Potentially Toxic Metals and Metalloids through Diverse Transporters: Metal-Specific Insights. Geomicrobiol. J. 2024, 41, 496–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolón-Cárdenas, G.A.; Hernández-Morales, A. Microbial Tolerance Strategies Against Cadmium Toxicity. In Cadmium Toxicity Mitigation; Jha, A.K., Kumar, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 147–168. ISBN 978-3-031-47390-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Tang, S.; Wei, H.; Yao, L.; Chen, Z.; Han, H.; Ji, M.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Tang, S.; et al. Reducing Cd Uptake by Wheat Through Rhizosphere Soil N-C Cycling and Bacterial Community Modulation by Urease-Producing Bacteria and Organo-Fe Hydroxide Coprecipitates. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Tang, S.; Deng, Z.; Makar, R.S.; Yao, L.; Han, H. Exopolysaccharide-Producing Strains Alter Heavy Metal Fates and Bacterial Communities in Soil Aggregates to Reduce Metal Uptake by Pakchoi. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1595142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulikova, N.A.; Perminova, I.V.; Kulikova, N.A.; Perminova, I.V. Interactions between Humic Substances and Microorganisms and Their Implications for Nature-like Bioremediation Technologies. Molecules 2021, 26, 2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Shao, S.; Yu, X.; Huang, M.; Qiu, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, H.; Shen, L. Evaluation of Microbial Metabolites in the Bioleaching of Rare Earth Elements from Ion-Adsorption Type Rare Earth Ore. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.C.; Datta, M.; Sharma, V. Chemistry, Microbiology, and Behaviour of Acid Soils. In Soil Acidity: Management Options for Higher Crop Productivity; Sharma, U.C., Datta, M., Sharma, V., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 121–322. ISBN 978-3-031-76357-1. [Google Scholar]

- Akinpelu, E.A.; Ntwampe, S.K.O.; Fosso-Kankeu, E.; Nchu, F.; Angadam, J.O. Performance of Microbial Community Dominated by Bacillus spp. in Acid Mine Drainage Remediation Systems: A Focus on the High Removal Efficiency of SO42−, Al3+, Cd2+, Cu2+, Mn2+, Pb2+, and Sr2+. Heliyon 2021, 7, e17661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Jiang, L.; Yang, J.; Guo, Z.; Li, K.; Peng, Y.; Ibrahim, N.; Liu, H.; Liang, Y.; Yin, H.; et al. Transport Behavior of Cd2+ in Highly Weathered Acidic Soils and Shaping in Soil Microbial Community Structure. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2024, 86, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Mao, H.; Yang, X.; Zhao, W.; Sheng, L.; Sun, S.; Du, X. Resilience Mechanisms of Rhizosphere Microorganisms in Lead-Zinc Tailings: Metagenomic Insights into Heavy Metal Resistance. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 292, 117956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebril, N.; Boden, R.; Braungardt, C. Cadmium Resistant Bacteria Mediated Cadmium Removal: A Systematic Review on Resistance, Mechanism and Bioremediation Approaches. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1002, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.-Y.; Liu, X.-J.; Fu, C.-A.; Gu, X.-F.; Lin, J.-Q.; Liu, X.-M.; Pang, X.; Lin, J.-Q.; Chen, L.-X.; Gao, X.-Y.; et al. Novel Strategy for Improvement of the Bioleaching Efficiency of Acidithiobacillus Ferrooxidans Based on the AfeI/R Quorum Sensing System. Minerals 2020, 10, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, R.; Hei, J.; Li, Y.; Al Farraj, D.A.; Noor, F.; Wang, S.; He, X. Effects of Humic Acid Fertilizer on the Growth and Microbial Network Stability of Panax Notoginseng from the Forest Understorey. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Song, G.; Zheng, Z.; Song, Z.; Mi, X.; Hua, J.; Wang, Z. Effect of Humic Substances on the Fraction of Heavy Metal and Microbial Response. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszkowski, M.; Kordala, N. The Role of Organic Materials in Shaping the Content of Trace Elements in Iron-Contaminated Soil. Materials 2025, 18, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Li, S.; Lei, X.; Sun, X.; Qin, L. Salt Stress-Induced Changes in Microbial Community Structures and Metabolic Processes Result in Increased Soil Cadmium Availability. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 782, 147125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Xie, T.; Wang, X.; Bai, J.; Tang, L.; Zhao, H.; Wei, W.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y. Metagenomic Analysis of Microbial Community and Function Involved in Cd-Contaminated Soil. BMC Microbiol. 2018, 18, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumactud, R.A.; Gorim, L.Y.; Thilakarathna, M.S. Impacts of Humic-Based Products on the Microbial Community Structure and Functions toward Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 977121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Use and Types of Alpha-Diversity Metrics in Microbial NGS—CD Genomics. Available online: https://www.cd-genomics.com/microbioseq/the-use-and-types-of-alpha-diversity-metrics-in-microbial-ngs.html (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Wyszkowska, J.; Borowik, A.; Zaborowska, M.; Kucharski, J. Evaluation of the Usefulness of Sorbents in the Remediation of Soil Exposed to the Pressure of Cadmium and Cobalt. Materials 2022, 15, 5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Niu, W.; Li, G.; Du, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Q.; Siddique, K.H.M. Crucial Role of Rare Taxa in Preserving Bacterial Community Stability. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 1397–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; He, J.-Z.; Singh, B.K.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Wang, J.-T.; Li, P.-P.; Zhang, Q.-B.; Han, L.-L.; Shen, J.-P.; Ge, A.-H.; et al. Rare Taxa Maintain the Stability of Crop Mycobiomes and Ecosystem Functions. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 1907–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Wen, Q.; Lin, X.; Luo, Z.; Qian, Z.; Li, M.; Deng, C.; et al. Rare Species Are Significant in Harsh Environments and Unstable Communities: Based on the Changes of Species Richness and Community Stability in Different Sub-Assemblages. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansupa, C.; Wahdan, S.F.M.; Hossen, S.; Disayathanoowat, T.; Wubet, T.; Purahong, W.; Sansupa, C.; Wahdan, S.F.M.; Hossen, S.; Disayathanoowat, T.; et al. Can We Use Functional Annotation of Prokaryotic Taxa (FAPROTAX) to Assign the Ecological Functions of Soil Bacteria? Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Peng, C.; Cao, H.; Song, J.; Gong, B.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Liang, M.; Lin, J.; et al. Microbial Functional Assemblages Predicted by the FAPROTAX Analysis Are Impacted by Physicochemical Properties, but C, N and S Cycling Genes Are Not in Mangrove Soil in the Beibu Gulf, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 139, 108887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Leung, P.M.; Wood, J.L.; Bay, S.K.; Hugenholtz, P.; Kessler, A.J.; Shelley, G.; Waite, D.W.; Franks, A.E.; Cook, P.L.M.; et al. Metabolic Flexibility Allows Bacterial Habitat Generalists to Become Dominant in a Frequently Disturbed Ecosystem. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2986–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, S.-T.; Song, J.; Kang, Y.-H.; Zhang, J.-L.; Chen, T.-S.; Li, Y.-R. Effects of Chemical Fertilization on Bacterial Community in Rhizosphere Soil of Sugarcane. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0327545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Peñuelas, J.; Cao, R.; Wang, L.; Yang, W. Decaying Logs and Gap Positions Jointly Mediate the Structure and Function of Soil Bacterial Community in the Forest Ecosystem. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 567, 122070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Guo, P. Treatment Performance and Microbial Community Dynamics in Vertical Flow Constructed Wetlands Integrated with Gradient Magnetic Fields. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 434, 132756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulfiqar, U.; Ayub, A.; Hussain, S.; Waraich, E.A.; El-Esawi, M.A.; Ishfaq, M.; Ahmad, M.; Ali, N.; Maqsood, M.F. Cadmium Toxicity in Plants: Recent Progress on Morpho-Physiological Effects and Remediation Strategies. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 22, 212–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaari, N.E.M.; Tajudin, M.T.F.M.; Khandaker, M.M.; Majrashi, A.; Alenazi, M.M.; Abdullahi, U.A.; Mohd, K.S. Cadmium Toxicity Symptoms and Uptake Mechanism in Plants: A Review. Braz. J. Biol. 2024, 84, e252143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros-Lajszner, E.; Wyszkowska, J.; Kucharski, J. Phytoremediation of Soil Contaminated with Nickel, Cadmium and Cobalt. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2021, 23, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, F.U.; Liqun, C.; Coulter, J.A.; Cheema, S.A.; Wu, J.; Zhang, R.; Wenjun, M.; Farooq, M. Cadmium Toxicity in Plants: Impacts and Remediation Strategies. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 211, 111887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, C.; Chen, J.; Coppens, F.; Inzé, D.; Verbruggen, N. Low Magnesium Status in Plants Enhances Tolerance to Cadmium Exposure. New Phytol. 2011, 192, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pál, M.; Janda, T.; Szalai, G. Interactions between Plant Hormones and Thiol-Related Heavy Metal Chelators. Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 85, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagorchev, L.; Seal, C.E.; Kranner, I.; Odjakova, M.; Zagorchev, L.; Seal, C.E.; Kranner, I.; Odjakova, M. A Central Role for Thiols in Plant Tolerance to Abiotic Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7405–7432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W. The Importance of Salicylic Acid, Humic Acid and Fulvic Acid on Crop Production. Lett. Drug Des. Discov. 2024, 21, 1465–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchaikovskaya, O.N.; Nechaev, L.V.; Yudina, N.V.; Mal’tseva, E.V. Quenching of Fluorescence of Phenolic Compounds and Modified Humic Acids by Cadmium Ions. Luminescence 2016, 31, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahemmat, M.; Farahbakhsh, M.; Kianirad, M. Humic Substances-Enhanced Electroremediation of Heavy Metals Contaminated Soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 312, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathor, P.; Gorim, L.Y.; Thilakarathna, M.S. Plant Physiological and Molecular Responses Triggered by Humic Based Biostimulants—A Way Forward to Sustainable Agriculture. Plant Soil 2023, 492, 31–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, D.; Wang, F.; Wei, Z.; Mao, N.; Wang, S.; Liu, X.; et al. Biodegradation of Humic Acids by Streptomyces Rochei to Promote the Growth and Yield of Corn. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 286, 127826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Qin, M.; Elahie, M.; Naeem, M.; Bashir, T.; Yasmin, H.; Younas, M.; Areeb, A.; Irfan, M.; Billah, M.; et al. Bacillus Pumilus Induced Tolerance of Maize (Zea mays L.) against Cadmium (Cd) Stress. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G. Editorial: Biostimulants in Agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakhin, O.I.; Lubyanov, A.A.; Yakhin, I.A.; Brown, P.H. Biostimulants in Plant Science: A Global Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- du Jardin, P. Plant Biostimulants: Definition, Concept, Main Categories and Regulation. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 196, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canellas, L.P.; Olivares, F.L. Physiological Responses to Humic Substances as Plant Growth Promoter. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2014, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, M.; Shokouhian, A.; Mohebodini, M. Effect of Humic Acid, Nitrogen Concentrations and Application Method on the Morphological, Yield and Biochemical Characteristics of Strawberry ‘Paros’. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2022, 22, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Qu, Z.; Ma, G.; Wang, W.; Dai, J.; Zhang, M.; Wei, Z.; Liu, Z. Humic Acid Modulates Growth, Photosynthesis, Hormone and Osmolytes System of Maize under Drought Conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 263, 107447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Reference Base|FAO SOILS PORTAL|Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-classification/world-reference-base/en/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- ISO 10390; In Soil Quality—Determination of PH. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Jaremko, D.; Kalembasa, D. A Comparison of Methods for the Determination of Cation Exchange Capacity of Soils/Porównanie Metod Oznaczania Pojemności Wymiany Kationów I Sumy Kationów Wymiennych W Glebach. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2014, 21, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klute, A. Methods of Soil Analysis. In American Society of Agronomy; Agronomy Monograph 9: Madison, WI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Wyszkowska, J.; Borowik, A.; Zaborowska, M.; Kucharski, J. Revitalization of Soil Contaminated by Petroleum Products Using Materials That Improve the Physicochemical and Biochemical Properties of the Soil. Molecules 2024, 29, 5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszkowska, J.; Borowik, A.; Zaborowska, M.; Kucharski, J. The Potential for Restoring the Activity of Oxidoreductases and Hydrolases in Soil Contaminated with Petroleum Products Using Perlite and Dolomite. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-ISO 11466:2002; Soil Quality—Extraction of Trace Elements Soluble in Aqua Regia. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. Available online: https://sklep.pkn.pl/normy/pn-iso-11466-2002p.html (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Bunt, J.S.; Rovira, A.D. Microbiological Studies of Some Subantarctic Soils. J. Soil Sci. 1955, 6, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, D.; Gray, F.R.G.; Williams, S.T. Methods of Studying Ecology of Soil Microorganism. In IBP Handbook; Blackweel Scientific Publication: Oxford/Edinburgh, UK, 1971; p. 19. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19721103172 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Sarathchandra, S.U.; Burch, G.; Cox, N.R. Growth Patterns of Bacterial Communities in the Rhizoplane and Rhizosphere of White Clover (Trifolium repens L.) and Perennial Ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) in Long-Term Pasture. Appl. Soil Ecol. 1997, 6, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leij, F.A.A.M.; Whipps, J.M.; Lynch, J.M. The Use of Colony Development for the Characterization of Bacterial Communities in Soil and on Roots. Microb. Ecol. 1994, 27, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “One for All, All for One” Bioinformatics Platform for Biological Big-Data Mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitikidou, K.; Milios, E.; Stampoulidis, A.; Pipinis, E.; Radoglou, K.; Kitikidou, K.; Milios, E.; Stampoulidis, A.; Pipinis, E.; Radoglou, K. Using Biodiversity Indices Effectively: Considerations for Forest Management. Ecologies 2024, 5, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Turmuhan, R.-G.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Wan, L. Five Years of Natural Vegetation Recovery in Three Forests of Karst Graben Area and Its Effects on Plant Diversity and Soil Properties. Forests 2025, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gihring, T.M.; Green, S.J.; Schadt, C.W. Massively Parallel rRNA Gene Sequencing Exacerbates the Potential for Biased Community Diversity Comparisons Due to Variable Library Sizes. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Gotelli, N.J.; Hsieh, T.C.; Sander, E.L.; Ma, K.H.; Colwell, R.K.; Ellison, A.M. Rarefaction and Extrapolation with Hill Numbers: A Framework for Sampling and Estimation in Species Diversity Studies. Ecol. Monogr. 2014, 84, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnes, G.R.; Bolker, B.; Bonebakker, L.; Gentleman, R.; Huber, W.; Liaw, A.; Lumley, T.; Maechler, M.; Magnusson, A.; Moeller, S.; et al. Gplots: Various R Programming Tools for Plotting Data. 2024. R Package Version 2.17.0. 2020. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gplots (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019; Available online: https://www.r-project.org (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Caspi, R.; Altman, T.; Billington, R.; Dreher, K.; Foerster, H.; Fulcher, C.A.; Holland, T.A.; Keseler, I.M.; Kothari, A.; Kubo, A.; et al. The MetaCyc Database of Metabolic Pathways and Enzymes and the BioCyc Collection of Pathway/Genome Databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D459–D471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Boulch, M.; Déhais, P.; Combes, S.; Pascal, G. The MACADAM Database: A MetAboliC pAthways DAtabase for Microbial Taxonomic Groups for Mining Potential Metabolic Capacities of Archaeal and Bacterial Taxonomic Groups. Database 2019, 2019, baz049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, S.; Parfrey, L.W.; Doebeli, M. Decoupling Function and Taxonomy in the Global Ocean Microbiome. Science 2016, 353, 1272–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberán, A.; Caceres Velazquez, H.; Jones, S.; Fierer, N. Hiding in Plain Sight: Mining Bacterial Species Records for Phenotypic Trait Information. mSphere 2017, 2, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Chen, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. SRplot: A Free Online Platform for Data Visualization and Graphing. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borowik, A.; Wyszkowska, J.; Zaborowska, M.; Kucharski, J. The Importance of Humic Acids in Shaping the Resistance of Soil Microorganisms and the Tolerance of Zea mays to Excess Cadmium in Soil. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412175

Borowik A, Wyszkowska J, Zaborowska M, Kucharski J. The Importance of Humic Acids in Shaping the Resistance of Soil Microorganisms and the Tolerance of Zea mays to Excess Cadmium in Soil. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412175

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorowik, Agata, Jadwiga Wyszkowska, Magdalena Zaborowska, and Jan Kucharski. 2025. "The Importance of Humic Acids in Shaping the Resistance of Soil Microorganisms and the Tolerance of Zea mays to Excess Cadmium in Soil" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412175

APA StyleBorowik, A., Wyszkowska, J., Zaborowska, M., & Kucharski, J. (2025). The Importance of Humic Acids in Shaping the Resistance of Soil Microorganisms and the Tolerance of Zea mays to Excess Cadmium in Soil. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12175. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412175