Innovative Colorimetric Neutral Red-Based Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (NR-LAMP) Assay: Transforming Rapid and Affordable Feline Leukemia Virus Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

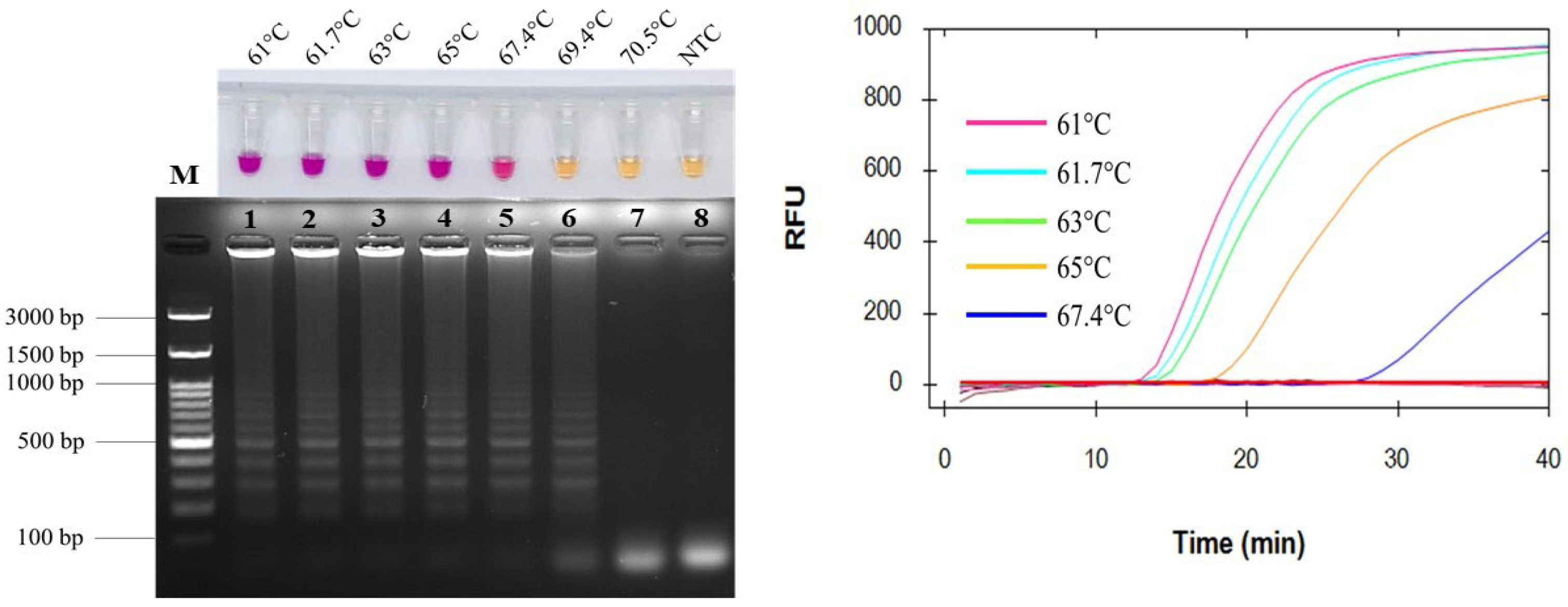

2.1. Optimization of Amplification Temperatures

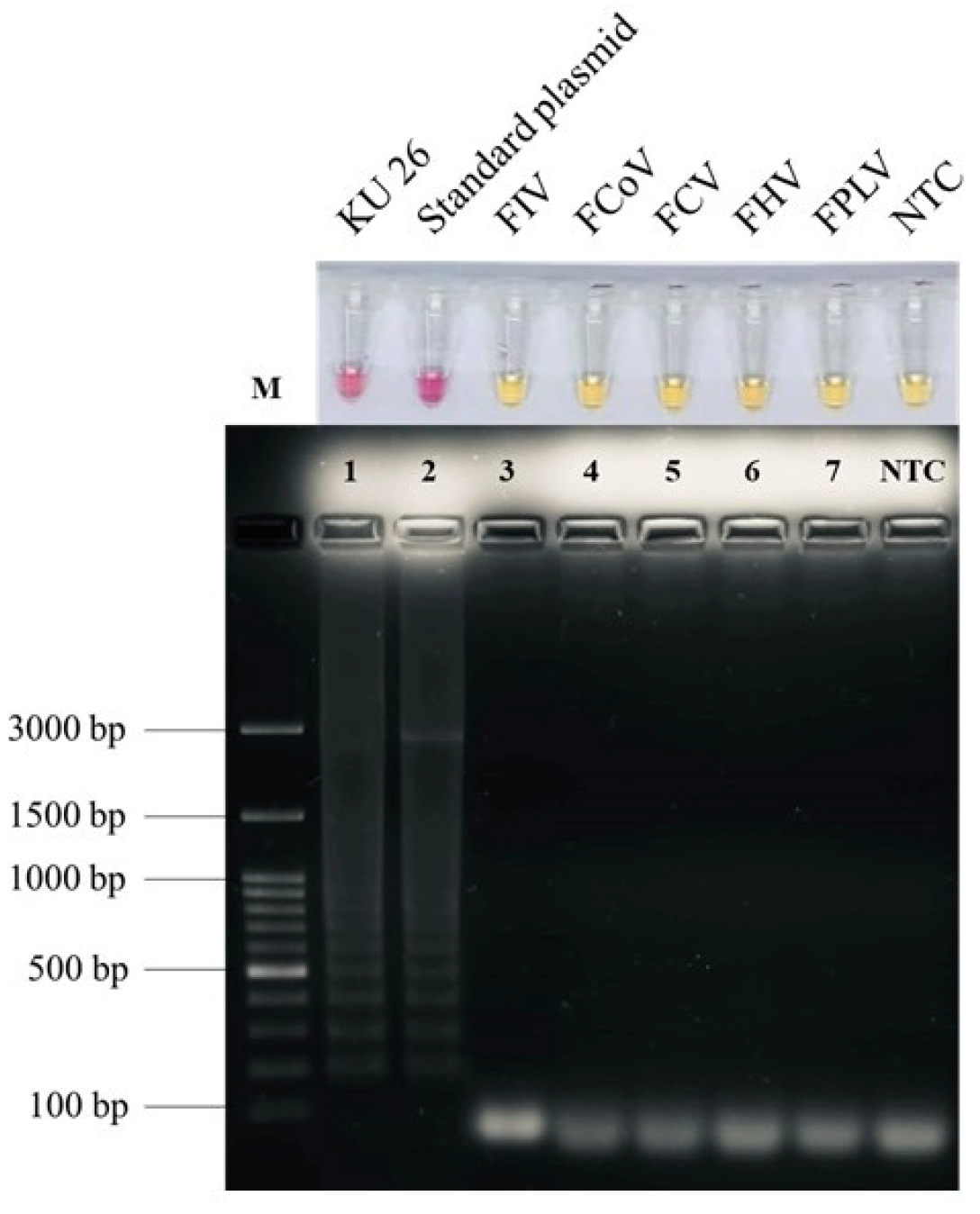

2.2. Specificity of Colorimetric LAMP for FeLV Detection

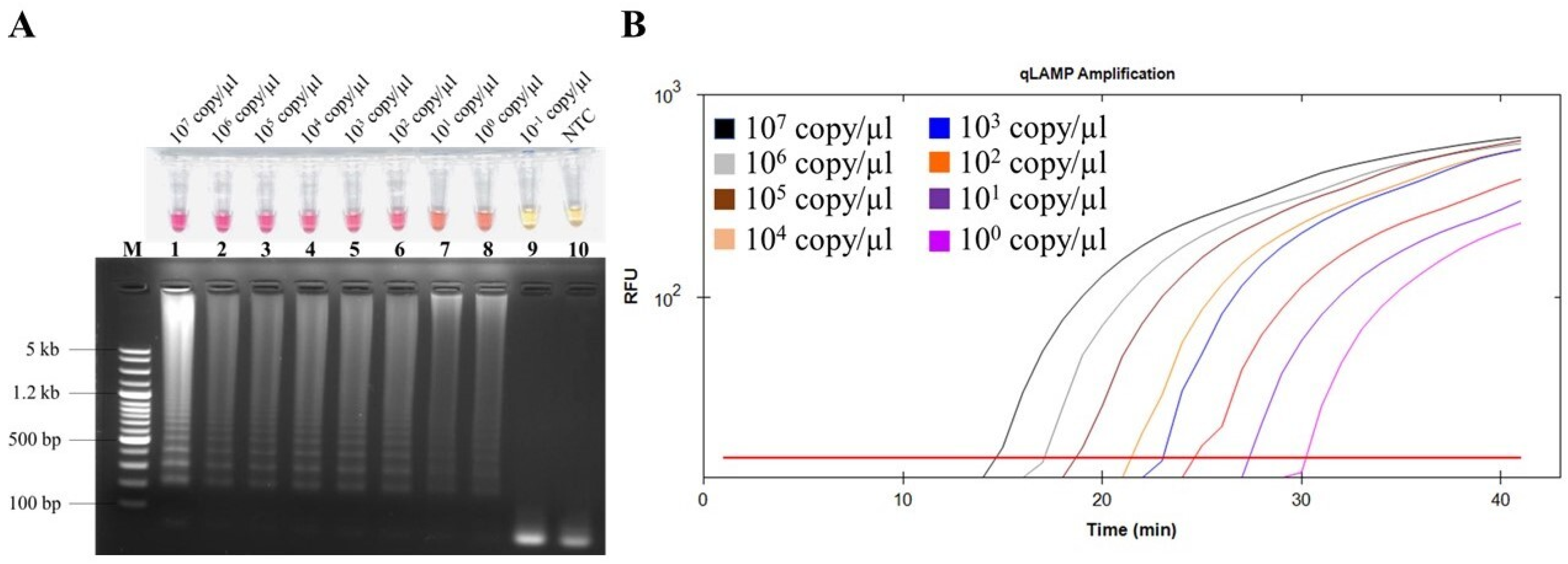

2.3. Detection Limit of Colorimetric LAMP for FeLV Detection

2.4. LAMP Performance with Clinical Samples and Cost Estimation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Statements

4.2. DNA Extraction from Blood Samples

4.3. Recombinant Plasmid Construction

4.4. LAMP Primer Design

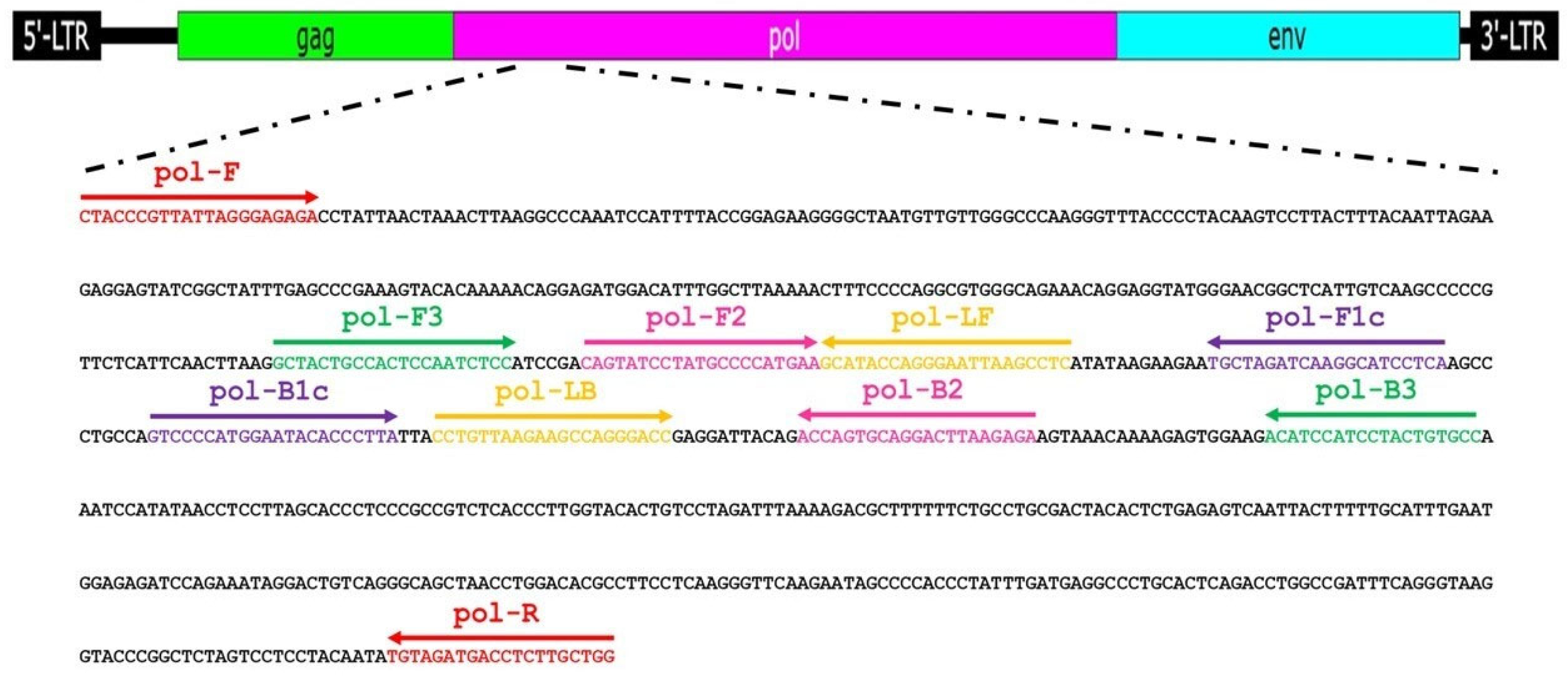

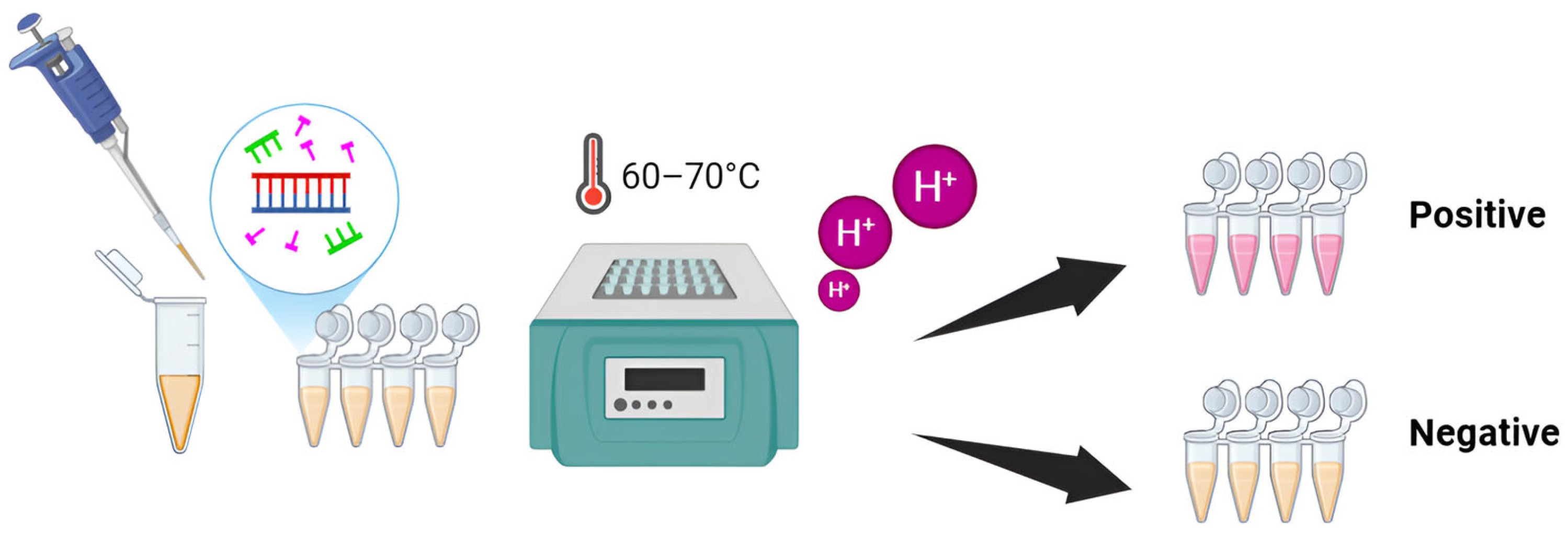

4.5. LAMP Reaction

4.6. PCR

4.7. LAMP Specificity

4.8. LAMP Detection Limit

4.9. Clinical Application of LAMP Method and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Willett, B.J.; Hosie, M.J. Feline Leukaemia Virus: Half a Century since Its Discovery. Vet. J. 2013, 195, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, E.S.; Hoover, E.A.; Vandewoude, S. A Retrospective Examination of Feline Leukemia Subgroup Characterization: Viral Interference Assays to Deep Sequencing. Viruses 2018, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojko, J.L.; Hoover, E.A.; Mathes, L.E.; Olsen, R.G.; Schalier, J.P. Pathogenesis of Experimental Feline Leukemia Virus Infection. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1979, 63, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleich, S.; Hartmann, K. Hematology and Serum Biochemistry of Feline Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected and Feline Leukemia Virus-Infected Cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2009, 23, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorny, P.; Speybroeck, N.; Verstraete, S.; Baeke, M.; De Becker, A.; Berkvens, D.; Vercruysse, J. Serological Survey Toxoplasma Gondii of a on Feline Immunodeficiency Virus and Feine Leukaemia Virus in Urban Stray Cats in Belgium. Vet. Rec. 2002, 151, 626–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandecchi, P.; Dell’Omodarme, M.; Magi, M.; Palamidessi, A.; Prati, M.C. Feline Leukaemia Virus (FeLV) and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus Infections in Cats in the Pisa District of Tuscany, and Attempts to Control FeLV Infection in a Colony of Domestic Cats by Vaccination. Vet. Rec. 2006, 158, 555–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.V.; Berry, B.T.; Roy-Burman, P. Nucleotide Sequence and Distinctive Characteristics of the Env Gene of Endogenous Feline Leukemia Provirus. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biezus, G.; Machado, G.; Ferian, P.E.; da Costa, U.M.; Pereira, L.H.H.d.S.; Withoeft, J.A.; Nunes, I.A.C.; Muller, T.R.; de Cristo, T.G.; Casagrande, R.A. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) in Cats of the State of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 63, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.K.; Scott, H.M.; Lachtara, J.L.; Crawford, P.C. Seroprevalence of Feline Leukemia Virus and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus Infection among Cats in North America and Risk Factors for Seropositivity. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2006, 228, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Washizu, T.; Toriyabe, K.; Motoyoshi, S.; Tomoda, I.; Pedersen, N. Feline Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Cats of Japan. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1989, 194, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bande, F.; Arshad, S.S.; Hassan, L.; Zakaria, Z.; Sapian, N.A.; Rahman, N.A.; Alazawy, A. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Feline Leukaemia Virus and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus in Peninsular Malaysia. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capozza, P.; Lorusso, E.; Colella, V.; Thibault, J.C.; Tan, D.Y.; Tronel, J.P.; Halos, L.; Beugnet, F.; Elia, G.; Nguyen, V.L.; et al. Feline Leukemia Virus in Owned Cats in Southeast Asia and Taiwan. Vet. Microbiol. 2021, 254, 109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westman, M.; Norris, J.; Malik, R.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Harvey, A.; McLuckie, A.; Perkins, M.; Schofield, D.; Marcus, A.; McDonald, M.; et al. The Diagnosis of Feline Leukaemia Virus (FeLV) Infection in Owned and Group-Housed Rescue Cats in Australia. Viruses 2019, 11, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luckman, C.; Gates, M.C. Epidemiology and Clinical Outcomes of Feline Immunodeficiency Virus and Feline Leukaemia Virus in Client-Owned Cats in New Zealand. J. Feline Med. Surg. Open Rep. 2017, 3, 2055116917729311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, A.L.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; O’Brien, S.J. Genomically Intact Endogenous Feline Leukemia Viruses of Recent Origin. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 4370–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, S.; Levy, J.; Hartmann, K.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Hosie, M.; Olah, G.; Denis, K.S. 2020 AAFP Feline Retrovirus Testing and Management Guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2020, 22, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, A.; Cattori, V.; Boenzli, E.; Riond, B.; Ossent, P.; Meli, M.L.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Lutz, H. Exposure of Cats to Low Doses of FeLV: Seroconversion as the Sole Parameter of Infection. Vet. Res. 2010, 41, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, K. Clinical Aspects of Feline Retroviruses: A Review. Viruses 2012, 4, 2684–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, A.C.; Tandon, R.; Cattori, V.; Niederer, E.; Riond, B.; Willi, B.; Lutz, H.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Cellular Segregation of Feline Leukemia Provirus and Viral RNA in Leukocyte Subsets of Long-Term Experimentally Infected Cats. Virus Res. 2007, 127, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulet, H.; Brunet, S.; Boularand, C.; Guiot, A.L.; Leroy, V.; Tartaglia, J.; Minke, J.; Audonnet, J.C.; Desmettre, P. Efficacy of a Canarypox Virus-Vectored Vaccine against Feline Leukaemia. Vet. Rec. 2003, 153, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciani, D.J.; Kensil, C.R.; Beltz, G.A.; Hung, C.h.; Cronier, J.; Aubert, A. Genetically-Engineered Subunit Vaccine against Feline Leukaemia Virus: Protective Immune Response in Cats. Vaccine 1991, 9, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, W.; Jarrett, O.; MacKey, L.; Laird, H.; Hood, C.; Hay, D. Vaccination against Feline Leukaemia Virus Using a Cell Membrane Antigen System. Int. J. Cancer 1975, 16, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Cattori, V.; Tandon, R.; Boretti, F.S.; Meli, M.L.; Riond, B.; Lutz, H. How Molecular Methods Change Our Views of FeLV Infection and Vaccination. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008, 123, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, A.N.; Mathiason, C.K.; Hoover, E.A. Re-Examination of Feline Leukemia Virus: Host Relationships Using Real-Time PCR. Virology 2005, 332, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arjona, A.; Barquero, N.; Doménech, A.; Tejerizo, G.; Collado, V.M.; Toural, C.; Martín, D.; Gomez-Lucia, E. Evaluation of a Novel Nested PCR for the Routine Diagnosis of Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV). J. Feline Med. Surg. 2007, 9, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagamine, K.; Hase, T.; Notomi, T. Accelerated Reaction by Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Using Loop Primers. Mol. Cell. Probes 2002, 16, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notomi, T.; Okayama, H.; Masubuchi, H.; Yonekawa, T.; Watanabe, K.; Amino, N.; Hase, T. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapichai, W.; Saejung, W.; Khumtong, K.; Boonkaewwan, C.; Tuanthap, S.; Lieberzeit, P.A.; Choowongkomon, K.; Rattanasrisomporn, J. Development of Colorimetric Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay for Detecting Feline Coronavirus. Animals 2022, 12, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Kitao, M.; Tomita, N.; Notomi, T. Real-Time Turbidimetry of LAMP Reaction for Quantifying Template DNA. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2004, 59, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S.M.G.; Ali, H.; Chase, C.C.L.; Cepica, A. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification for Diagnosis of 18 World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) Notifiable Viral Diseases of Ruminants, Swine and Poultry. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2015, 16, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamsingnok, P.; Rapichai, W.; Rattanasrisomporn, A.; Rungsuriyawiboon, O.; Choowongkomon, K.; Rattanasrisomporn, J. Comparison of PCR, Nested PCR, and RT-LAMP for Rapid Detection of Feline Calicivirus Infection in Clinical Samples. Animals 2024, 14, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saejung, W.; Khumtong, K.; Rapichai, W.; Ratanabunyong, S.; Rattanasrisomporn, A.; Choowongkomon, K.; Rungsuriyawiboon, O.; Rattanasrisomporn, J. Detection of Feline Immunodeficiency Virus by Neutral Red-Based Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay. Vet. World 2024, 17, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khumtong, K.; Rapichai, W.; Saejung, W.; Khamsingnok, P.; Meecharoen, N.; Ratanabunyong, S.; Van Dong, H.; Tuanthap, S.; Rattanasrisomporn, A.; Choowongkomon, K.; et al. Colorimetric Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification with Xylenol Orange Targeting Nucleocapsid Gene for Detection of Feline Coronavirus Infection. Viruses 2025, 17, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazawa, T.; Jarrett, O. Feline Leukaemia Virus Proviral DNA Detected by Polymerase Chain Reaction in Antigenaemic but Non-Viraemic (‘discordant’) Cats. Arch. Virol. 1997, 142, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongtako, W.; Sirinarumitr, T. Development of TaqMan® Real-Time Reverse Transcription- Polymerase Chain Reaction for the Quantification of Feline Leukemia Virus Load. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2009, 43, 153–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cattori, V.; Tandon, R.; Pepin, A.; Lutz, H.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Rapid Detection of Feline Leukemia Virus Provirus Integration into Feline Genomic DNA. Mol. Cell. Probes 2006, 20, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, R.; Cattori, V.; Gomes-Keller, M.A.; Meli, M.L.; Golder, M.C.; Lutz, H.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Quantitation of Feline Leukaemia Virus Viral and Proviral Loads by TaqMan® Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Virol. Methods 2005, 130, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinches, M.D.G.; Helps, C.R.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.J.; Egan, K.; Jarrett, O.; Tasker, S. Diagnosis of Feline Leukaemia Virus Infection by Semi-Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2007, 9, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacharoje, S.; Techangamsuwan, S.; Chaichanawongsaroj, N. Rapid Characterization of Feline Leukemia Virus Infective Stages by a Novel Nested Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) and Reverse Transcriptase-RPA. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, W.F.H.; Crawford, E.M.; Martin, W.B.; Davie, F.A. Leukæmia in the Cat: A Virus-like Particle associated with Leukæmia (Lymphosarcoma). Nature 1964, 202, 567–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, H.; Addie, D.; Belák, S.; Boucraut-Baralon, C.; Egberink, H.; Frymus, T.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.; Hartmann, K.; Hosie, M.J.; Lloret, A.; et al. Feline Leukaemia: ABCD Guidelines on Prevention and Management. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2009, 11, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boenzli, E.; Hadorn, M.; Hartnack, S.; Huder, J.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; Lutz, H. Detection of Antibodies to the Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) Transmembrane Protein P15E: An Alternative Approach for Serological FeLV Detection Based on Antibodies to P15E. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 2046–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, N.; Mori, Y.; Kanda, H.; Notomi, T. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) of Gene Sequences and Simple Visual Detection of Products. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quyen, T.L.; Ngo, T.A.; Bang, D.D.; Madsen, M.; Wolff, A. Classification of Multiple DNA Dyes Based on Inhibition Effects on Real-Time Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): Prospect for Point of Care Setting. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Hou, T.; Li, S. A Novel One-Pot Rapid Diagnostic Technology for COVID-19. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1154, 338310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Dai, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Hou, Q.; Ou, Y.; Ding, Y.; Ma, B.; Chen, H.; Li, M.M.; et al. Development of a Potential Penside Colorimetric LAMP Assay Using Neutral Red for Detection of African Swine Fever Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stranieri, A.; Lauzi, S.; Giordano, A.; Paltrinieri, S. Reverse Transcriptase Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification for the Detection of Feline Coronavirus. J. Virol. Methods 2017, 243, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günther, S.; Felten, S.; Wess, G.; Hartmann, K.; Weber, K. Detection of Feline Coronavirus in Effusions of Cats with and without Feline Infectious Peritonitis Using Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification. J. Virol. Methods 2018, 256, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techangamsuwan, S.; Radtanakatikanon, A.; Thanawongnuwech, R. Development and Application of Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (RT-LAMP) for Feline Coronavirus Detection. Thai J. Vet. Med. 2013, 43, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saechue, B.; Kamiyama, N.; Wang, Y.; Fukuda, C.; Watanabe, K.; Soga, Y.; Goto, M.; Dewayani, A.; Ariki, S.; Hirose, H.; et al. Development of a Portable Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification System to Detect the E1 Region of Chikungunya Virus in a Cost-Effective Manner. Genes Cells 2020, 25, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, W.; Matsumura, Y.; Thongchankaew-Seo, U.; Yamazaki, Y.; Nagao, M. Development of a Point-of-Care Test to Detect SARS-CoV-2 from Saliva Which Combines a Simple RNA Extraction Method with Colorimetric Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Detection. J. Clin. Virol. 2021, 136, 104760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyrc, K.; Milewska, A.; Potempa, J. Development of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay for Detection of Human Coronavirus-NL63. J. Virol. Methods 2011, 175, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, L.M.; Niessen, L. Development and Optimization of a Group-Specific Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Assay for the Detection of Patulin-Producing Penicillium Species. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 298, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, L.M.; Mann, M.A.; Marek, D.N.; Niessen, L. Development and Optimization of a Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Assay for the Species-Specific Detection of Penicillium expansum. Food Microbiol. 2021, 95, 103681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuertes-Perez, S.; Hilgarth, M.; Vogel, R.F. Development of a Rapid Detection Method for Photobacterium Spp. Using Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 334, 108805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenpanich, P.; Mungkung, A.; Seeviset, N. A PH Sensitive, Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay for Detection of Salmonella in Food. Sci. Eng. Health Stud. 2020, 2020, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, L. The Application of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Assays for the Rapid Diagnosis of Food-Borne Mycotoxigenic Fungi. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 23, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Sun, N.; Liu, M.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Pei, R. Neutral Red as a Specific Light-up Fluorescent Probe for i-Motif DNA. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 14330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- abcam. Fluorophore Table. Available online: https://www.abcam.com/ps/pdf/protocols/fluorophore%20table.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Ramírez, H.; Autran, M.; García, M.M.; Carmona, M.Á.; Rodríguez, C.; Martínez, H.A. Genotyping of Feline Leukemia Virus in Mexican Housecats. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markoulatos, P.; Siafakas, N.; Moncany, M. Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction: A Practical Approach. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2002, 16, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Guo, J.; Shen, P.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D. Visual and Rapid Detection of Two Genetically Modified Soybean Events Using Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Method. Food Anal. Methods 2010, 3, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemoto, J.; Sugawara, C.; Akahane, K.; Hashimoto, K.; Kojima, T.; Ikedo, M.; Konuma, H.; Yukiko, H.K. Rapid and Specific Detection of the Thermostable Direct Hemolysin Gene in Vibrio Parahaemolyticus by Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuta, S.; Ohishi, K.; Yoshida, K.; Mizukami, Y.; Ishida, A.; Kanbe, M. Development of Immunocapture Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification for the Detection of Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus from Chrysanthemum. J. Virol. Methods 2004, 121, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Guo, J.; Chen, R.; Grisham, M.P.; Que, Y. Development of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification for Detection of Leifsonia xyli subsp. xyli in Sugarcane. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 357692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X. Reverse Transcription Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification of DNA for Detection of Potato Virus Y. Plant Dis. 2005, 89, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wu, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, L.; Ying, Y. Portable PH-Inspired Electrochemical Detection of DNA Amplification. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 8416–8419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njiru, Z.K.; Mikosza, A.S.J.; Matovu, E.; Enyaru, J.C.K.; Ouma, J.O.; Kibona, S.N.; Thompson, R.C.A.; Ndung’u, J.M. African Trypanosomiasis: Sensitive and Rapid Detection of the Sub-Genus Trypanozoon by Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) of Parasite DNA. Int. J. Parasitol. 2008, 38, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangchuen, A.; Chaumpluk, P.; Suriyasomboon, A.; Ekgasit, S. Colorimetric Detection of Ehrlichia Canis via Nucleic Acid Hybridization in Gold Nano-Colloids. Sensors 2014, 14, 14472–14487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, M.A. Critical Insight into Recombinase Polymerase Amplification Technology. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 22, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Duan, J.; Chen, J.; Ding, S.; Cheng, W. Recent Advances in Rolling Circle Amplification-Based Biosensing Strategies—A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1148, 238187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NR-LAMP | Conventional PCR | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | PPV (%) (95% CI) | NPV (%) (95% CI) | κ Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | ||||||

| Positive | 71 | 0 | 71 | 97.3 (90.45–99.67) | 100.0 (86.3–100) | 100.0 (94.94–100) | 92.6 (76.11–98.0) | 0.9 |

| Negative | 2 | 25 | 27 | |||||

| Total | 73 | 25 | 98 | |||||

| Method | Target | LOD (copy/µL) | Amplification Time (min) | Sensitivity (%)/Specificity (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR-LAMP | pol gene | 100 | 40 | 97.3/100 | This work |

| nPCR | U3LTR-gag | 100 | >60 | NA | [34] |

| RT-qPCR | U3LTR | 8.3 | 44.5 | NA | [35] |

| qPCR | U3LTR | 103 | >60 | NA | [36] |

| qPCR | U3LTR | 180 | >60 | NA | [37] |

| RT-qPCR | LTR | NA | >60 | 92/99 | [38] |

| RPA | U3LTR | NA | 10 min | 95.89/100 | [39] |

| Hospital | Cost per Reaction (USD) a |

|---|---|

| Private Veterinary Hospital | 29.66 |

| Kasetsart University Veterinary Teaching Hospital | 17.79 |

| NR-LAMP (this study) | 1.04 |

| Primer Name | Primer Sequence (5′ ⟶ 3′) | Assay | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| pol-F | CYAMCCRTTATTRGGDAGAGA | PCR | [60] |

| pol-R | CCAGCAAGAGGTCATCTACA | ||

| pol-F3 | GCTACYGCYACTCCAATYTCC | LAMP | This work |

| pol-B3 | GGCACMGTRGGATGGATGT | ||

| pol-LF | GRGGYTTAATTCCYTGGTAIGC | ||

| pol-LB | CCYGTYAARAAGCCWGGRACC | ||

| pol-FIPBR-TO-BREAK (F1C-F2) | TGAGGATRCCTTGRTCYAGCA-CAGTAYCCYATGCCCCATRAR | ||

| pol-BIPBR-TO-BREAK (B1C-B2) | GTCCCCATGGAATACWCCCYTA-TCTCTTAARTCYTGYACTGGT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rapichai, W.; Khamsingnok, P.; Wachirachaikarn, A.; Laodim, T.; Dong, H.V.; Meecharoen, N.; Ratanabunyong, S.; Khaoiam, T.; Tuanthap, S.; Rattanasrisomporn, A.; et al. Innovative Colorimetric Neutral Red-Based Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (NR-LAMP) Assay: Transforming Rapid and Affordable Feline Leukemia Virus Detection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411793

Rapichai W, Khamsingnok P, Wachirachaikarn A, Laodim T, Dong HV, Meecharoen N, Ratanabunyong S, Khaoiam T, Tuanthap S, Rattanasrisomporn A, et al. Innovative Colorimetric Neutral Red-Based Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (NR-LAMP) Assay: Transforming Rapid and Affordable Feline Leukemia Virus Detection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411793

Chicago/Turabian StyleRapichai, Witsanu, Piyamat Khamsingnok, Anyalak Wachirachaikarn, Thawee Laodim, Hieu Van Dong, Nianrawan Meecharoen, Siriluk Ratanabunyong, Thanawat Khaoiam, Supansa Tuanthap, Amonpun Rattanasrisomporn, and et al. 2025. "Innovative Colorimetric Neutral Red-Based Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (NR-LAMP) Assay: Transforming Rapid and Affordable Feline Leukemia Virus Detection" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411793

APA StyleRapichai, W., Khamsingnok, P., Wachirachaikarn, A., Laodim, T., Dong, H. V., Meecharoen, N., Ratanabunyong, S., Khaoiam, T., Tuanthap, S., Rattanasrisomporn, A., Pairor, S., Choowongkomon, K., Tansakul, N., Lieberzeit, P. A., & Rattanasrisomporn, J. (2025). Innovative Colorimetric Neutral Red-Based Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (NR-LAMP) Assay: Transforming Rapid and Affordable Feline Leukemia Virus Detection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411793