Coordinated Auxin–Cytokinin–Nitrogen Signaling Orchestrates Root Suckering in Populus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Rapid Induction System and Temporal Transcriptome Dynamics of Root Suckering

2.2. WGCNA Reveals Stage-Specific Key Pathway and Genes During Root Suckering

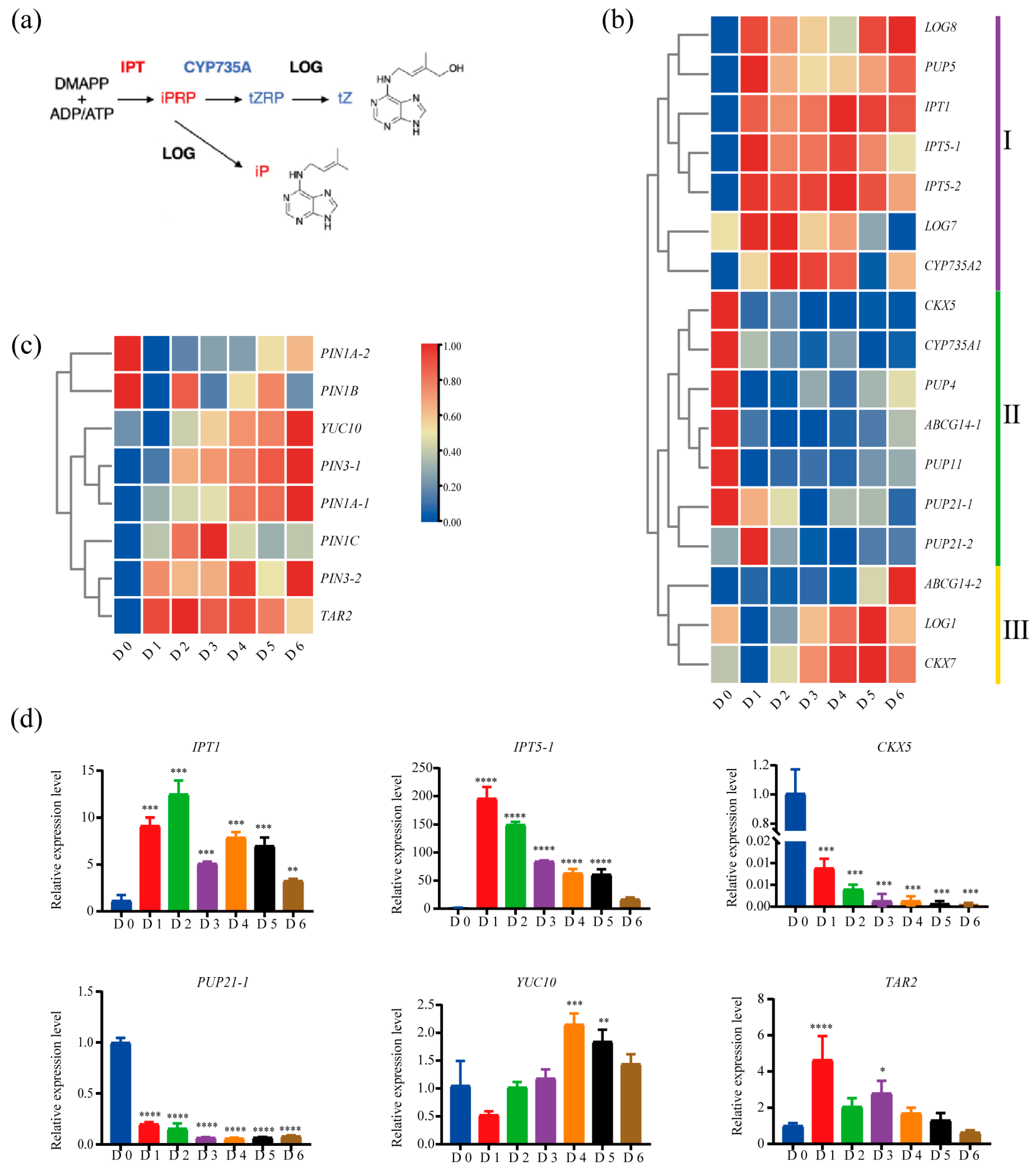

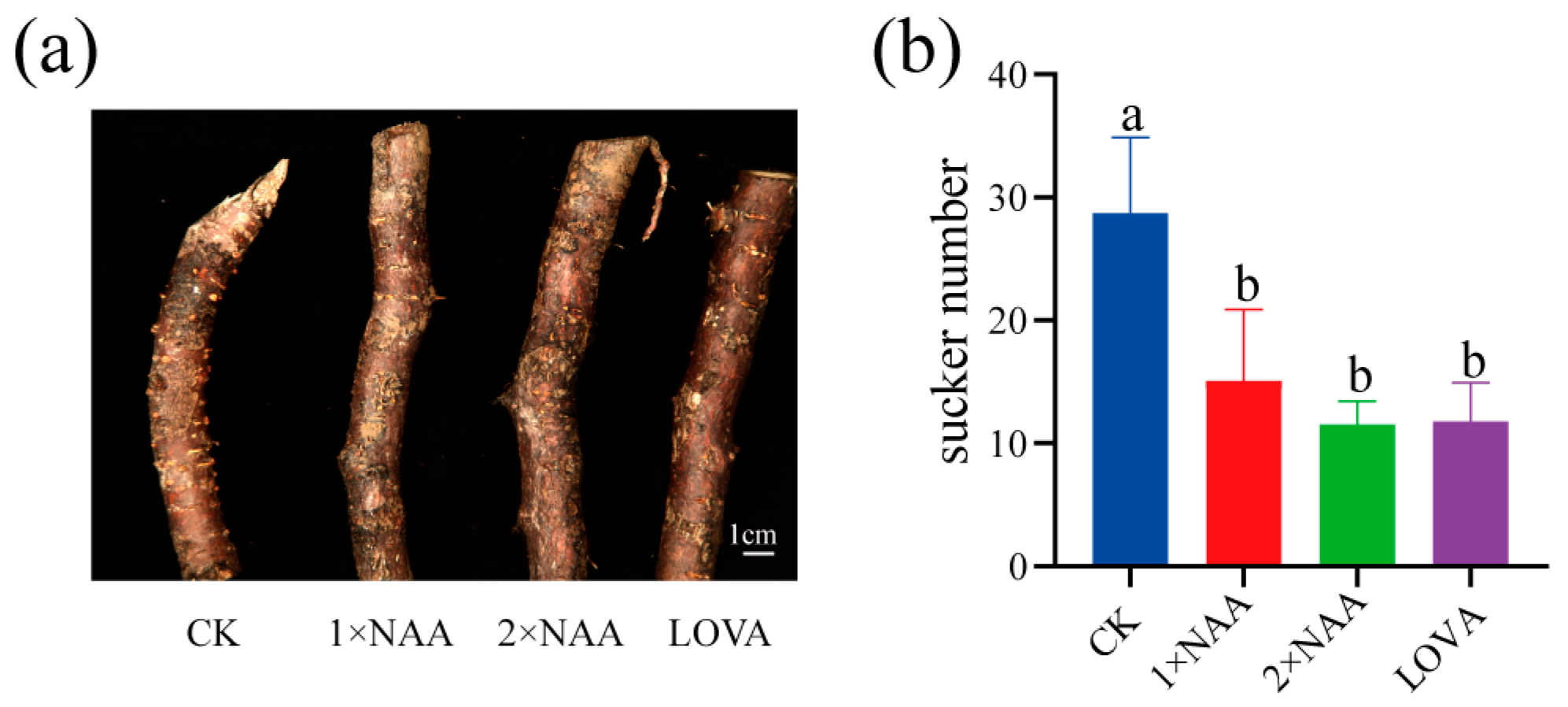

2.3. Molecular Pathways of Auxin and Cytokinin Governing SAM Formation in Poplar Root Suckering

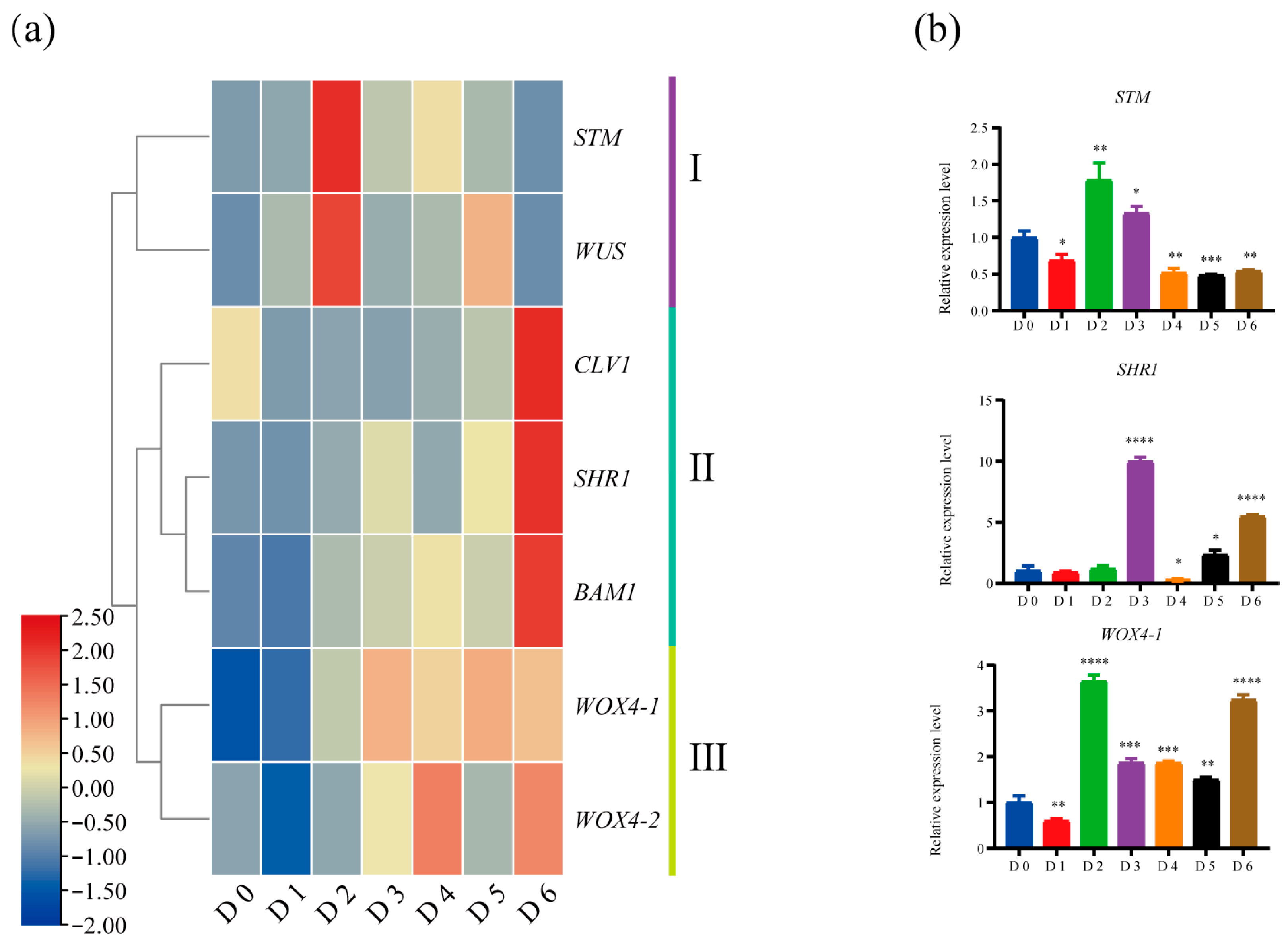

2.4. Reprogramming of Core Meristem Regulators During De Novo SAM Formation in Root Suckering

3. Discussion

3.1. Cytological Features and Key Molecular Triggers of Populus Root Suckering

3.2. Auxin–Cytokinin–Nitrogen Crosstalk Controls SAM Formation in Populus Root Suckering

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Induction of Root Suckers

4.2. Semi-Thin Sectioning and Microscopy

4.3. RNA Extraction, cDNA Library Construction and High-Throughput Sequencing

4.4. Bioinformatic Analysis

4.5. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

4.6. Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

4.7. Sucker Induction Under Hormone Treatments

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPIBA | α-(p-chlorophenoxy) isobutyric acid |

| CKX | cytokinin oxidase |

| WUS | WUSCHEL |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

| AHK4 | Arabidopsis histidine kinase 4 |

| SHR1 | SHORT-ROOT1 |

References

- Ko, D.; Kang, J.; Kiba, T.; Park, J.; Kojima, M.; Do, J.; Kim, K.Y.; Kwon, M.; Endler, A.; Song, W.Y.; et al. Arabidopsis ABCG14 is essential for the root-to-shoot translocation of cytokinin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7150–7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.Z.; Zhang, F.; Song, H.S. Breeding technology and application of Populus tomentosa. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 2022, 28, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.C. Cultivation techniques for fast-growing poplar root sprouts. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2021, 07, 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.S.; Bai, Y.M.; Sun, Y.G. Cutting and grafting propagation techniques of Populus ‘Shanxin’. Sci. Technol. West China 2007, 6, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, X.Y. Reflections and practices on the new round of genetic improvement strategies for Populus tomentosa. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2016, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.M.; Wang, Z.M.; Wang, Z.Y. Experimental study on cultivation techniques of fast-growing poplar root sprout forests in the Hebei plain. J. Hebei For. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B.R.; Lieffers, V.J.; Landhausser, S.M.; Comeau, P.G.; Greenway, K.J. An analysis of sucker regeneration of trembling aspen. Can. J. For. Res. 2003, 33, 1169–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.T.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhao, Y.G. Study on rapid propagation methods of elite Populus tomentosa trees. J. Beijing For. Univ. 1986, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, D.C.; Li, J.W.; Chen, W.Q.; Peng, C.; Li, J.Q. Development and growth of root suckers of Populus euphratica in different forest gaps in Ejina Oasis. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2009, 29, 1954–1961. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.K.; Jiao, A.Y.; Ling, H.B. Characteristics of root sprouting propagation of Populus euphratica under different irrigation patterns. Arid Zone Res. 2022, 39, 1133–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Schier, G.A. Promotion of sucker development on Populus tremuloides root cuttings by an antiauxin. Can. J. For. Res. 1975, 5, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hélia, C.; Augusto, P.; Catherine, B.; Sara, P.; Uwe, D. Editorial: Advances on the biological mechanisms involved in adventitious root formation: From signaling to morphogenesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 867651–867653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Levesque, M.P.; Vernoux, T.; Jung, J.W.; Paquette, A.J.; Gallagher, K.L.; Wang, J.Y.J.; Blilou, I.; Scheres, B.; Benfey, P.N. An evolutionarily conserved mechanism delimiting SHR movement defines a single layer of endodermis in plants. Science 2007, 316, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schier, G.A. Physiological Research on Adventitious Shoot Development in Aspen Roots; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Washington, DC, USA, 1981; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhai, L.; Strauss, S.H.; Yer, H.; Li, Y. Transgenic reduction of cytokinin levels in roots inhibits root-sprouting in Populus. Plant Physiol. 2019, 180, 1788–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Shao, X.; Xue, P.; Tian, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Wu, Y. Root sprouting ability and growth dynamics of the rootsuckers of Emmenopterys henryi, a rare and endangered plant endemic to China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 389, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P. Dancing with hormones: A current perspective of nitrate signaling and regulation in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schier, G.A. Origin and development of aspen root suckers. Can. J. For. Res. 1973, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.B. Cambial activity, root habit and sucker shoot development in two species of Poplar. New Phytol. 1935, 34, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, A.; Tamaoki, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuoka, M. The expression of tobacco knotted1-type class 1 homeobox genes correspond to regions predicted by the cytohistological zonation model. Plant J. 1999, 18, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.C.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Cell signaling within the shoot meristem. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2000, 3, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.K.; Girke, T.; Pasala, S.; Xie, M.; Reddy, G.V. Gene expression map of the Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem stem cell niche. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 4941–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, C.; Long, J.; Yamaguchi, J.; Serikawa, K.; Hake, S. A knotted1-like homeobox gene in Arabidopsis is expressed in the vegetative meristem and dramatically alters leaf morphology when overexpressed in transgenic plants. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 1859–1876. [Google Scholar]

- Laux, T.; Mayer, K.F.; Berger, J.; Jürgens, G. The WUSCHEL gene is required for shoot and floral meristem integrity in Arabidopsis. Development 1996, 122, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrizzi, K.; Moussian, B.; Haecker, A.; Levin, J.Z.; Laux, T. The SHOOT MERISTEMLESS gene is required for maintenance of undifferentiated cells in Arabidopsis shoot and floral meristems and acts at a different regulatory level than the meristem genes WUSCHEL and ZWILLE. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010, 10, 967–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.H.; Zhou, C.; Li, Y.J.; Yu, Y.; Tang, L.P.; Zhang, W.J.; Yao, W.J.; Huang, R.; Laux, T.; Zhang, X.S. Integration of pluripotency pathways regulates stem cell maintenance in the Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 22561–22571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.Q.; Lian, H.; Zhou, C.M.; Xu, L.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, J.W. A two-step model for de novo activation of WUSCHEL during plant shoot regeneration. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallois, J.L.; Nora, F.R.; Mizukami, Y.; Sablowski, R. WUSCHEL induces shoot stem cell activity and developmental plasticity in the root meristem. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.E. Cell signalling at the shoot meristem. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, J.C. The CLV-WUS stem cell signaling pathway: A roadmap to crop yield optimization. Plants 2018, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eljebbawi, A.; Dolata, A.; Strotmann, V.I.; Stahl, Y.; Considine, M. Stem cell quiescence and dormancy in plant meristems. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 6022–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Liu, Z.; Qiao, M.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Xiang, F. ARR12 promotes de novo shoot regeneration in Arabidopsis thaliana via activation of WUSCHEL expression. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2017, 59, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.J.; Cheng, Z.J.; Sang, Y.L.; Zhang, M.M.; Rong, X.F.; Wang, Z.W.; Tang, Y.Y.; Zhang, X.S. Type-B ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATORs specify the shoot stem cell niche by dual regulation of WUSCHEL. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1357–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, Y.; Ikeuchi, M.; Jiao, Y.; Prasad, K.; Su, Y.H.; Xiao, J.; Xu, L.; Yang, W.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Plant regeneration in the new era: From molecular mechanisms to biotechnology applications. Sci. China Life Sci. 2024, 67, 1338–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.J.; Wang, L.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Su, Y.H.; Li, W.; Sun, T.T.; Zhao, X.Y.; Li, X.G.; et al. Pattern of auxin and cytokinin responses for shoot meristem induction results from the regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis by AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3. Plant Physiol. 2013, 161, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zaitoon, Y.M.; Al-Ramamneh, E.A.M.; Al Tawaha, A.R.; Alnaimat, S.M.; Almomani, F.A. Comparative coexpression analysis of indole synthase and tryptophan synthase a reveals the independent production of auxin via the cytosolic free indole. Plants 2023, 12, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.L.; Xie, Q.; Weijers, D.; Liu, C.M. The anaphase promoting complex initiates zygote division in Arabidopsis through degradation of cyclin B1. Plant J. 2016, 86, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.H.; Liu, Y.B.; Zhang, X.S. Auxin–cytokinin interaction regulates meristem development. Mol. Plant 2011, 4, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.A.H.; Jones, A.; Godin, C.; Traas, J. Systems analysis of shoot apical meristem growth and development: Integrating hormonal and mechanical signaling. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 3907–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiba, T.; Takei, K.; Kojima, M.; Sakakibara, H. Side-chain modification of cytokinins controls shoot growth in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 2013, 27, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen, J. The cytokinin side chain commands shooting. Dev. Cell 2013, 27, 371–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, H. CYTOKININS: Activity, biosynthesis, and translocation. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieber, J.J.; Schaller, G.E. Cytokinin signaling in plant development. Development 2018, 145, dev149344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, C.; Novak, O.; Wei, Z.; Gou, M.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Yang, H.; Cai, Y.; Strnad, M. Arabidopsis ABCG14 protein controls the acropetal translocation of root-synthesized cytokinins. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, T.; Motyka, V.; Strnad, M.; Schmülling, T. Regulation of plant growth by cytokinin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10487–10492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroha, T.; Tokunaga, H.; Kojima, M.; Ueda, N.; Ishida, T.; Nagawa, S.; Fukuda, H.; Sugimoto, K.; Sakakibara, H. Functional analyses of LONELY GUY cytokinin-activating enzymes reveal the importance of the direct activation pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 3152–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chickarmane, V.S.; Gordon, S.P.; Tarr, P.T.; Heisler, M.G.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Cytokinin signaling as a positional cue for patterning the apical-basal axis of the growing Arabidopsis shoot meristem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 4002–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartrina, I.; Otto, E.; Strnad, M.; Werner, T.; Schmülling, T. Cytokinin regulates the activity of reproductive meristems, flower organ size, ovule formation, and thus seed yield in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.K.; Tavakkoli, M.; Xie, M.; Girke, T.; Reddy, G.V. A high-resolution gene expression map of the Arabidopsis shoot meristem stem cell niche. Development 2014, 141, 2735–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friml, J.; Vieten, A.; Sauer, M.; Weijers, D.; Schwarz, H.; Hamann, T.; Offringa, R.; Jürgens, G. Efflux-dependent auxin gradients establish the apical-basal axis of Arabidopsis. Nature 2003, 426, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, A.W.; Bartel, B. Auxin: Regulation, action, and interaction. Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 707–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normanly, J. Approaching cellular and molecular resolution of auxin biosynthesis and metabolism. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a001594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, J.; Nilsson, J.; Mellerowicz, E.; Berglund, A.; Nilsson, P.; Hertzberg, M.; Sandberg, G.R. A high-resolution transcript profile across the wood-forming meristem of Poplar identifies potential regulators of cambial stem cell identity. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 2278–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.; Yoon, E.K.; Dhar, S.; Oh, J.; Lim, J. A SHORTROOT-mediated transcriptional regulatory network for vascular development in the Arabidopsis shoot. J. Plant Biol. 2022, 65, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helariutta, Y.; Fukaki, H.; Wysocka-Diller, J.; Nakajima, K.; Jung, J.; Sena, G.; Hauser, M.T.; Benfey, P.N. The SHORT-ROOT gene controls radial patterning of the Arabidopsis root through radial signaling. Cell 2000, 101, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsbecker, A.; Lee, J.Y.; Roberts, C.J.; Dettmer, J.; Lehesranta, S.; Zhou, J.; Lindgren, O.; Moreno-Risueno, M.A.; Vatén, A.; Thitamadee, S.; et al. Cell signalling by microRNA165/6 directs gene dose-dependent root cell fate. Nature 2010, 465, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Su, H.; Cao, H.; Wei, H.; Fu, X.; Jiang, X.; Song, Q.; He, X.; Xu, C.; Luo, K. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR7 integrates gibberellin and auxin signaling via interactions between DELLA and AUX/IAA proteins to regulate cambial activity in poplar. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 2688–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Strable, J.; Shimizu, R.; Koenig, D.; Sinha, N.; Scanlon, M.J. WOX4 promotes procambial development. Plant Physiol. 2009, 152, 1346–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schier, G.A.; Zasada, J.C. Role of carbohydrate reserves in the development of root suckers in Populus tremuloides. Can. J. For. Res. 1973, 3, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukoglu, M.; Nilsson, J.; Zheng, B.; Chaabouni, S.; Nilsson, O. WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX 4 (WOX 4)-like genes regulate cambial cell division activity and secondary growth in Populus trees. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 642–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.C.; Song, R.; Zheng, S.Q.; Li, T.T.; Zhang, B.L.; Gao, X.; Lu, Y.T. Coordination of plant growth and abiotic stress responses by Tryptophan Synthase β Subunit1 through modulating tryptophan and ABA homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 973–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, Y.; Kawamura, A.; Suzuki, T.; Segami, S.; Maeshima, M.; Polyn, S.; De Veylder, L.; Sugimoto, K. Transcriptional activation of auxin biosynthesis drives developmental reprogramming of differentiated cells. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 4348–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ckurshumova, W.; Smirnova, T.; Marcos, D.; Zayed, Y.; Berleth, T. Irrepressible MONOPTEROS/ARF5 promotes de novo shoot formation. New Phytol. 2014, 204, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, S.M.; Habash, D.Z. The importance of cytosolic glutamine synthetase in nitrogen assimilation and recycling. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Zhang, C.; Suglo, P.; Sun, S.; Wang, M.; Su, T. l-Aspartate: An essential metabolite for plant growth and stress acclimation. Molecules 2021, 26, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, G.; Takahashi, H. How does nitrogen shape plant architecture? J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 4415–4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Qin, R.; Liu, T.; Yu, M.; Yang, T.; Xu, G. OsASN1 plays a critical role in asparagine-dependent rice development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhou, F.; Du, W.; Dou, J.; Xu, Y.; Gao, W.; Chen, G.; Zuo, X.; Sun, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. Knockdown of Asparagine synthetase by RNAi suppresses cell growth in human melanoma cells and epidermoid carcinoma cells. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2016, 63, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Zheng, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, B. Knockdown of Asparagine synthetase (ASNS) suppresses cell proliferation and inhibits tumor growth in gastric cancer cells. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 51, 1220–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krall, A.S.; Xu, S.; Graeber, T.G.; Braas, D.; Christofk, H.R. Asparagine promotes cancer cell proliferation through use as an amino acid exchange factor. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funayama, K.; Kojima, S.; Tabuchi-Kobayashi, M.; Sawa, Y.; Nakayama, Y.; Hayakawa, T.; Yamaya, T. Cytosolic glutamine synthetase1;2 is responsible for the primary assimilation of ammonium in rice roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, M.; Ishiyama, K.; Kusano, M.; Fukushima, A.; Kojima, S.; Hanada, A.; Kanno, K.; Hayakawa, T.; Seto, Y.; Kyozuka, J.; et al. Lack of cytosolic glutamine synthetase1;2 in vascular tissues of axillary buds causes severe reduction in their outgrowth and disorder of metabolic balance in rice seedlings. Plant J. 2015, 81, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, M.; Ishiyama, K.; Kojima, S.; Kojima, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Yamaya, T.; Hayakawa, T. Lack of cytosolic Glutamine Synthetase1;2 activity reduces nitrogen-dependent biosynthesis of cytokinin required for axillary bud outgrowth in rice seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Qu, B.; Li, W.; Zhao, X.; Teng, W.; Ma, W.; Ren, Y.; Li, B.; Li, Z.; Tong, Y. The nitrate-inducible NAC transcription factor TaNAC2-5A controls nitrate response and increases wheat yield. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 1991–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, J.; Chen, R.; Chen, J.; Zong, J.; Li, L.; Hao, D.; Guo, H. Review: Nitrogen acquisition, assimilation, and seasonal cycling in perennial grasses. Plant Sci. 2024, 5, 112054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Xu, X.; Li, X.; Xu, M.; Hu, M.; Xiong, Y.; Feng, J.; Wu, H.; Zhu, H.; Su, T. New insight into aspartate metabolic pathways in populus: Linking the root responsive isoenzymes with amino acid biosynthesis during incompatible interactions of fusarium solani. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, A.; Williams, B.A.; Mccue, K.; Schaeffer, L.; Wold, B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; Mccarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Biogeosciences 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, H.; Lyu, W.; Chen, Y.; Ding, L.; Zheng, L.; Wang, H. Coordinated Auxin–Cytokinin–Nitrogen Signaling Orchestrates Root Suckering in Populus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412172

Pang H, Lyu W, Chen Y, Ding L, Zheng L, Wang H. Coordinated Auxin–Cytokinin–Nitrogen Signaling Orchestrates Root Suckering in Populus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412172

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Hongying, Wanwan Lyu, Yajuan Chen, Liping Ding, Lin Zheng, and Hongzhi Wang. 2025. "Coordinated Auxin–Cytokinin–Nitrogen Signaling Orchestrates Root Suckering in Populus" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412172

APA StylePang, H., Lyu, W., Chen, Y., Ding, L., Zheng, L., & Wang, H. (2025). Coordinated Auxin–Cytokinin–Nitrogen Signaling Orchestrates Root Suckering in Populus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12172. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412172