From Deep-Sea Natural Product to Optimized Therapeutics: Computational Design of Marizomib Analogs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Structure Alignment and Similarity Analysis

2.2. Molecular Docking Results, Binding Pose, and Binding Affinity Analysis

2.3. Frontier Molecular Orbital (HOMO–LUMO) Results of Marizomib and Its Analogs

2.4. Pharmacophore Modeling Results

2.5. MD Simulations Reveal Structural Stability and Interaction Profiles of Marizomib and Its Analogs

2.6. MM/PBSA Free Energy Analysis and Per-Residue Decomposition

2.7. In Silico Pharmacokinetics and ADMET Profiling of Marizomib and Its Analogs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Three-Dimensional Structure Modifications and MM2 Energy Minimization

4.2. Three-Dimensional Structure Alignment and Similarity Analysis

4.3. Molecular Docking Simulations and Binding Affinity Analysis

4.4. HOMO–LUMO Analysis of MZB Analogs

4.5. Three-Dimensional Pharmacophore Modeling

4.6. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation for Structural Stability and Interaction Analysis

4.7. Molecular Mechanics/Poisson–Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) Calculations

4.8. In Silico Pharmacokinetics and ADMET Evaluation

5. Limitations and Future Works

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMET | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity |

| AIRs | Ambiguous interaction restraints |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| DDI | Drug–drug interaction |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| FEP | Free-energy perturbation |

| FMO | Frontier molecular orbital |

| GAFF2 | General amber force field |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| HADDOCK | High ambiguity driven protein-protein docking |

| HBA | Hydrogen bond acceptor |

| HBD | Hydrogen bond donor |

| HOMO | Highest occupied molecular orbital |

| LBD | Ligand-binding domain |

| LUMO | Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| MM/PBSA | Molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann surface area |

| MOE | Molecular operating environment |

| NPT | Number of particles, pressure, and temperature |

| NVT | Number of particles, volume, and temperature |

| PME | Particle mesh Ewald |

| PSMB5 | Proteasome subunit beta type-5 |

| PRODIGY | Protein binding energy prediction |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation |

| RMSF | Root mean square fluctuation |

| RoG | Radius of gyration |

| SASA | Solvent-accessible surface area |

| SCF | Self-consistent field |

| SPCE | Single point charge extended |

| SPR | Surface plasmon resonance |

| STP | Single-trajectory protocol |

| TPSA | Topological polar surface area |

| UPS | Ubiquitin–proteasome system |

References

- Shetty, C.; Tamatta, R.; Dhas, N.; Singh, A.K. Evolving therapesutic strategies in glioblastoma: Traditional approaches and novel interventions. 3 Biotech 2025, 15, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyan, A.; Ghorbanlo, M.; Eslami, M.; Jahanshahi, M.; Ziaei, E.; Salami, A.; Mokhtari, K.; Shahpasand, K.; Farahani, N.; Meybodi, T.E.; et al. Glioblastoma multiforme: Insights into pathogenesis, key signaling pathways, and therapeutic strategies. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angom, R.S.; Nakka, N.M.R.; Bhattacharya, S. Advances in Glioblastoma Therapy: An Update on Current Approaches. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, M.; Cao, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Ren, B.; Wang, L.; Goh, B.C. Blood-Brain Barrier Conquest in Glioblastoma Nanomedicine: Strategies, Clinical Advances, and Emerging Challenges. Cancers 2024, 16, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikitsh, J.L.; Chacko, A.M. Pathways for small molecule delivery to the central nervous system across the blood-brain barrier. Perspect. Med. Chem. 2014, 6, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.-Y.; Lee, H.-Y. Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1670–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Cho, J.; Song, E.J. Ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) as a target for anticancer treatment. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2020, 43, 1144–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Dou, Q.P. The ubiquitin-proteasome system as a prospective molecular target for cancer treatment and prevention. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2010, 11, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaudeau, T.A.; Smith, D.M. A Practical Review of Proteasome Pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2019, 71, 170–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S. Proteasome Inhibitors for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Cancers 2020, 12, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Cheng, T.; Liu, T.; Xu, W.; Liu, D.; Dai, J.; Cai, S.; Guan, Y.; Ye, T.; Cheng, X. Safety of proteasome inhibitor drugs for the treatment of multiple myeloma post-marketing: A pharmacovigilance investigation based on the FDA adverse event reporting system. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2024, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Klockow, J.L.; Zhang, M.; Lafortune, F.; Chang, E.; Jin, L.; Wu, Y.; Daldrup-Link, H.E. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM): An overview of current therapies and mechanisms of resistance. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 171, 105780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piskorz, W.M.; Krętowski, R.; Cechowska-Pasko, M. Marizomib (Salinosporamide A) Promotes Apoptosis in A375 and G361 Melanoma Cancer Cells. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, K.D.; Shende, V.V.; Chen, P.Y.; Trivella, D.B.B.; Gulder, T.A.M.; Vellalath, S.; Romo, D.; Moore, B.S. Enzymatic assembly of the salinosporamide γ-lactam-β-lactone anticancer warhead. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potts, B.C.; Albitar, M.X.; Anderson, K.C.; Baritaki, S.; Berkers, C.; Bonavida, B.; Chandra, J.; Chauhan, D.; Cusack, J.C., Jr.; Fenical, W.; et al. Marizomib, a proteasome inhibitor for all seasons: Preclinical profile and a framework for clinical trials. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2011, 11, 254–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groll, M.; Huber, R.; Potts, B.C. Crystal structures of Salinosporamide A (NPI-0052) and B (NPI-0047) in complex with the 20S proteasome reveal important consequences of beta-lactone ring opening and a mechanism for irreversible binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 5136–5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, K.; Lloyd, G.K.; Abraham, V.; MacLaren, A.; Burrows, F.J.; Desjardins, A.; Trikha, M.; Bota, D.A. Marizomib activity as a single agent in malignant gliomas: Ability to cross the blood-brain barrier. Neuro Oncol. 2016, 18, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, P.; Reijneveld, J.; Gorlia, T.; Dhermain, F.; De Vos, F.; Vanlancker, M.; O’Callaghan, C.; Rhun, E.; Bent, M.; Mason, W.; et al. P14.124 EORTC 1709/CCTG CE.8: A phase III trial of marizomib in combination with standard temozolomide-based radiochemotherapy versus standard temozolomide-based radiochemotherapy alone in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, iii98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.M.; Lim, S.J.; Tong, J.C. Recent advances in computer-aided drug design. Brief. Bioinform. 2009, 10, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaiq, N.; Dermawan, D. Computational Investigation of Montelukast and Its Structural Derivatives for Binding Affinity to Dopaminergic and Serotonergic Receptors: Insights from a Comprehensive Molecular Simulation. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dermawan, D.; Alotaiq, N. Computational analysis of antimicrobial peptides targeting key receptors in infection-related cardiovascular diseases: Molecular docking and dynamics insights. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowska, J.; Giżyńska, M.; Karpowicz, P.; Sowik, D.; Trepczyk, K.; Hennenberg, F.; Chari, A.; Giełdoń, A.; Pierzynowska, K.; Gaffke, L.; et al. Blm10-Based Compounds Add to the Knowledge of How Allosteric Modulators Influence Human 20S Proteasome. ACS Chem. Biol. 2025, 20, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sülzen, H.; Fajtova, P.; O’Donoghue, A.J.; Boura, E.; Silhan, J. Structural insights into Salinosporamide A mediated inhibition of the human 20S proteasome. Molecules 2025, 30, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, P.; Gorlia, T.; Reijneveld, J.C.; de Vos, F.; Idbaih, A.; Frenel, J.S.; Le Rhun, E.; Sepulveda, J.M.; Perry, J.; Masucci, G.L.; et al. Marizomib for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma: A randomized phase 3 trial. Neuro Oncol. 2024, 26, 1670–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Park, J.; Han, E.T.; Han, J.H.; Park, W.S.; Chun, W. Identification of Malaria-Selective Proteasome β5 Inhibitors Through Pharmacophore Modeling, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.S.; Binduhayyim, R.I.H.; Gurumurthy, V.; Alshadidi, A.A.F.; Aldosari, L.I.N.; Okshah, A.; Kuruniyan, M.S.; Dermawan, D.; Avetisyan, A.; Mosaddad, S.A.; et al. Dental biomaterials redefined: Molecular docking and dynamics-driven dental resin composite optimization. BMC Oral. Health 2024, 24, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.S.; Binduhayyim, R.I.H.; Gurumurthy, V.; Alshadidi, A.A.F.; Bavabeedu, S.S.; Vyas, R.; Dermawan, D.; Naseef, P.P.; Mosaddad, S.A.; Heboyan, A. In silico assessment of biocompatibility and toxicity: Molecular docking and dynamics simulation of PMMA-based dental materials for interim prosthetic restorations. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2024, 35, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faleye, O.S.; Boya, B.R.; Lee, J.-H.; Choi, I.; Lee, J. Halogenated Antimicrobial Agents to Combat Drug-Resistant Pathogens. Pharmacol. Rev. 2024, 76, 90–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verteramo, M.L.; Ignjatović, M.M.; Kumar, R.; Wernersson, S.; Ekberg, V.; Wallerstein, J.; Carlström, G.; Chadimová, V.; Leffler, H.; Zetterberg, F.; et al. Interplay of halogen bonding and solvation in protein-ligand binding. iScience 2024, 27, 109636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujjar, R.; El Mazouni, F.; White, K.L.; White, J.; Creason, S.; Shackleford, D.M.; Deng, X.; Charman, W.N.; Bathurst, I.; Burrows, J.; et al. Lead optimization of aryl and aralkyl amine-based triazolopyrimidine inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenase with antimalarial activity in mice. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 3935–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribas, J.; Cubero, E.; Luque, F.J.; Orozco, M. Theoretical Study of Alkyl-π and Aryl-π Interactions. Reconciling Theory Experiment. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 67, 7057–7065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alex, A.; Millan, D.S.; Perez, M.; Wakenhut, F.; Whitlock, G.A. Intramolecular hydrogen bonding to improve membrane permeability and absorption in beyond rule of five chemical space. MedChemComm 2011, 2, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, K.M. Functional materials based on molecules with hydrogen-bonding ability: Applications to drug co-crystals and polymer complexes. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 180564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, H.; Olson, J.; Abt, D. A Short Synthesis of γ-Lactams Via the Spontaneous Ring Expansion of β-Lactams. Synth. Commun. 1992, 22, 2729–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drossman, H.; Johnson, H.; Mill, T. Structure activity relationships for environmental processes 1: Hydrolysis of esters and carbamates. Chemosphere 1988, 17, 1509–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Enzyme Models—From Catalysis to Prodrugs. Molecules 2021, 26, 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, F.; Ba, X.; Wu, Y. Synthesis of Fused-Ring Derivatives Containing Bifluorenylidene Units via Pd-Catalyzed Tandem Multistep Suzuki Coupling/Heck Cyclization Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 15964–15968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-L.; Schneider, G. Scaffold Architecture and Pharmacophoric Properties of Natural Products and Trade Drugs: Application in the Design of Natural Product-Based Combinatorial Libraries. J. Comb. Chem. 2001, 3, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dassault Systèmes. BIOVIA Discovery Studio; Dassault Systèmes: San Diego, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman, V.; Gaiser, J.; Demekas, D.; Roy, A.; Xiong, R.; Wheeler, T.J. Do Molecular Fingerprints Identify Diverse Active Drugs in Large-Scale Virtual Screening? (No). Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Gao, K.; Nguyen, D.D.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, G.-W.; Pan, F. Algebraic graph-assisted bidirectional transformers for molecular property prediction. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Skolnick, J. Utility of the Morgan Fingerprint in Structure-Based Virtual Ligand Screening. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 5363–5370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsi, M.; Reymond, J.-L. One chiral fingerprint to find them all. J. Cheminformatics 2024, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guex, N.; Peitsch, M.C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 2714–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R.A.; Jabłońska, J.; Pravda, L.; Vařeková, R.S.; Thornton, J.M. PDBsum: Structural summaries of PDB entries. Protein Sci. 2018, 27, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Ho, P.; Chen, C.H. Activation and inhibition of the proteasome by betulinic acid and its derivatives. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 4955–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, C.; Boelens, R.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J. HADDOCK: A Protein−Protein Docking Approach Based on Biochemical or Biophysical Information. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 1731–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zundert, G.C.P.; Rodrigues, J.; Trellet, M.; Schmitz, C.; Kastritis, P.L.; Karaca, E.; Melquiond, A.S.J.; van Dijk, M.; de Vries, S.J.; Bonvin, A. The HADDOCK2.2 Web Server: User-Friendly Integrative Modeling of Biomolecular Complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangone, A.; Bonvin, A. PRODIGY: A Contact-based Predictor of Binding Affinity in Protein-protein Complexes. Bio-Protocol 2017, 7, e2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, J.; Henneberg, F.; Mata, R.A.; Tittmann, K.; Schneider, T.R.; Stark, H.; Bourenkov, G.; Chari, A. The inhibition mechanism of human 20S proteasomes enables next-generation inhibitor design. Science 2016, 353, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Rives, J.; Jorgensen, W.L. Performance of B3LYP Density Functional Methods for a Large Set of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidault, X.; Chaudhuri, S. How Accurate Can Crystal Structure Predictions Be for High-Energy Molecular Crystals? Molecules 2023, 28, 4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Zafar, M.; Hussain, S.; Asghar, M.A.; Khera, R.A.; Imran, M.; Abookleesh, F.L.; Akram, M.Y.; Ullah, A. Influence of End-Capped Modifications in the Nonlinear Optical Amplitude of Nonfullerene-Based Chromophores with a D−π–A Architecture: A DFT/TDDFT Study. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 23532–23548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Z.; Ou, Q.; Mao, Y.; Yang, J.; Lande, A.; Plasser, F.; Liang, W.; Shuai, Z.; Shao, Y. Elucidating the Electronic Structure of a Delayed Fluorescence Emitter via Orbital Interactions, Excitation Energy Components, Charge-Transfer Numbers, and Vibrational Reorganization Energies. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 2712–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Aguiar, A.S.N.; de Carvalho, L.B.R.; Gomes, C.M.; Castro, M.M.; Martins, F.S.; Borges, L.L. Computational Insights into the Antioxidant Activity of Luteolin: Density Functional Theory Analysis and Docking in Cytochrome P450 17A1. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolber, G.; Langer, T. LigandScout: 3-D pharmacophores derived from protein-bound ligands and their use as virtual screening filters. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2005, 45, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronk, S.; Páll, S.; Schulz, R.; Larsson, P.; Bjelkmar, P.; Apostolov, R.; Shirts, M.R.; Smith, J.C.; Kasson, P.M.; van der Spoel, D.; et al. GROMACS 4.5: A high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaiq, N.; Dermawan, D.; Elwali, N.E. Leveraging Therapeutic Proteins and Peptides from Lumbricus Earthworms: Targeting SOCS2 E3 Ligase for Cardiovascular Therapy through Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaiq, N.; Dermawan, D. Evaluation of Structure Prediction and Molecular Docking Tools for Therapeutic Peptides in Clinical Use and Trials Targeting Coronary Artery Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermawan, D.; Alotaiq, N. Unveiling Pharmacological Mechanisms of Bombyx mori (Abresham), a Traditional Arabic Unani Medicine for Ischemic Heart Disease: An Integrative Molecular Simulation Study. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.S.; Vaddamanu, S.K.; Dermawan, D.; Mosaddad, S.A.; Heboyan, A. Investigating the role of temperature and moisture on the degradation of 3D-printed polymethyl methacrylate dental materials through molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, LLC. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 2.4; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Couch, G.S.; Greenblatt, D.M.; Meng, E.C.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogolari, F.; Brigo, A.; Molinari, H. Protocol for MM/PBSA Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Proteins. Biophys. J. 2003, 85, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genheden, S.; Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA methods to estimate ligand-binding affinities. Expert. Opin. Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hou, T. Develop and test a solvent accessible surface area-based model in conformational entropy calculations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermawan, D.; Alsenani, F.; Elwali, N.E.; Alotaiq, N. Therapeutic potential of earthworm-derived proteins: Targeting NEDD4 for cardiovascular disease intervention. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 15, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Tresanco, M.; Valdés-Tresanco, M.; Valiente, P.; Moreno Frias, E. gmx_MMPBSA: A New Tool to Perform End-State Free Energy Calculations with GROMACS. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 6281–6291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, T.; Freyss, J.; von Korff, M.; Rufener, C. DataWarrior: An open-source program for chemistry aware data visualization and analysis. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrödinger, LLC. Schrödinger Release 2025-3: QikProp; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

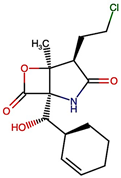

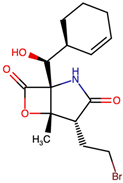

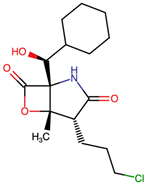

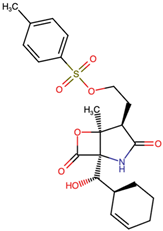

| Molecule | Modification Category | Tanimoto Similarity (FP2) | SMILES | 2D Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

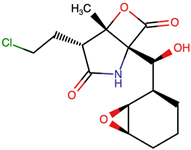

| MZB | N/A | 1.000 | C[C@]12[C@H](C(=O)N[C@]1(C(=O)O2)[C@H]([C@H]3CCCC=C3)O)CCCl |  |

| MZBMOD-1 | Halogenation | 0.927 | C[C@@]12OC(=O)[C@@]1(NC(=O)[C@@H]2CCBr)[C@@H](O)[C@H]1CCCC=C1 |  |

| MZBMOD-4 | Halogenation | 0.909 | C[C@@]12OC(=O)[C@@]1(NC(=O)[C@@H]2CCCCl)[C@@H](O)C1CCCCC1 |  |

| MZBMOD-22 | Alkyl/Aryl Substitutions | 0.601 | CC(C)COC(=O)C1C2OC3(CN(C4CCCC4)C(=O)C13)C=C2 |  |

| MZBMOD-25 | Alkyl/Aryl Substitutions | 0.847 | CC1=CC=C(C=C1)S(=O)(=O)OCC[C@H]1C(=O)N[C@@]2([C@@H](O)[C@H]3CCCC=C3)C(=O)O[C@@]12C |  |

| MZBMOD-36 | Hydroxyl/Ether Modifications | 0.900 | C[C@@]12OC(=O)[C@@]1(NC(=O)[C@@H]2CCCl)[C@@H](O)[C@H]1CCC[C@H]2O[C@@H]12 |  |

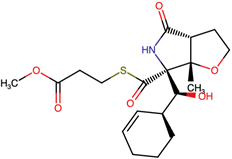

| MZBMOD-38 | Hydroxyl/Ether Modifications | 0.721 | COC(=O)CCSC(=O)[C@@]1(NC(=O)[C@@H]2CCO[C@]12C)[C@@H](O)[C@H]1CCCC=C1 |  |

| MZBMOD-50 | Lactone/Lactam Ring Modifications | 0.626 | C[C@H]1C=C[C@H]2CCCC[C@@H]2[C@H]1C(=O)[C@H]1[C@@H]2OC(=O)[C@@H]3CCN(C1=O)[C@]23O |  |

| MZBMOD-56 | Lactone/Lactam Ring Modifications | 0.565 | CCOC(=O)CN1CC23OC(C=C2)C(C3C1=O)C(=O)NC1CCCC1 |  |

| MZBMOD-68 | Ester Modifications | 0.449 | CCOC(=O)[C@H]1CCCN1C(=O)C(=O)C1(CCCCC1)OC |  |

| MZBMOD-72 | Ester Modifications | 0.446 | CCOC(=O)C1CCCCN1C(=O)C(=O)C1(CCCCC1)OC |  |

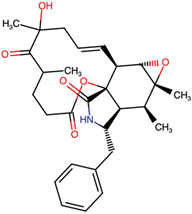

| MZBMOD-77 | Fused/Polycyclic/Complex Cyclized | 0.626 | C[C@H]1[C@H]2[C@H](CC3=CC=CC=C3)NC(=O)[C@]22OC(=O)CCC(C)C(=O)C(C)(O)C/C=C/[C@H]2[C@@H]2O[C@]12C |  |

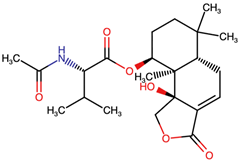

| MZBMOD-79 | Fused/Polycyclic/Complex Cyclized | 0.542 | CC(C)[C@H](NC(C)=O)C(=O)O[C@H]1CCC(C)(C)[C@@H]2CC=C3C(=O)OC[C@]3(O)[C@@]12C |  |

| Complex | HADDOCK Score (a.u.) | Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Van der Waals Energy | Electrostatic Energy | Desolvation Energy | RMSD | Hydrogen Bonds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSMB5_MZB | −27.1 ± 0.4 | −7.13 | −22.3 ± 0.4 | −10.1 ± 1.4 | −3.8 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | Arg19, Thr21, Gly23, Gly47 |

| PSMB5_BA | −22.4 ± 0.9 | −6.98 | −16.6 ± 0.8 | −9.1 ± 5.3 | −2.5 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | Gly47 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-77 | −34.8 ± 0.4 | −8.09 | −29.4 ± 0.5 | −14.0 ± 2.6 | −4.0 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | Arg19, Thr21, Gly23, Gly47 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-79 | −33.8 ± 0.4 | −7.83 | −27.0 ± 0.5 | −37.5 ± 1.8 | −3.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | Arg19, Thr21, Gly23, Gly47 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-93 | −28.2 ± 0.2 | −7.39 | −22.1 ± 0.6 | −42.2 ± 3.3 | −2.1 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.0 | Arg19, Thr21, Gly23, Gly47 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-50 | −33.3 ± 0.2 | −7.37 | −29.0 ± 0.3 | −20.6 ± 5.1 | −2.3 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | Thr1, Arg19, Thr21, Gly47 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-99 | −28.7 ± 1.4 | −7.30 | −27.0 ± 1.0 | −1.3 ± 7.2 | −1.6 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | Arg19, Thr21, Gly47 |

| Complex | CC | CO | CN | CX | OO | OX | NO | NN | NX | XX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSMB5_MZB | 1363 | 852 | 521 | 21 | 128 | 6 | 132 | 24 | 2 | 0 |

| PSMB5_BA | 1269 | 793 | 511 | 33 | 91 | 4 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-77 | 1950 | 1269 | 687 | 34 | 184 | 9 | 179 | 21 | 1 | 0 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-79 | 1620 | 1104 | 588 | 28 | 174 | 11 | 170 | 17 | 1 | 0 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-93 | 1324 | 838 | 535 | 23 | 131 | 10 | 142 | 32 | 1 | 0 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-50 | 1426 | 1040 | 533 | 18 | 189 | 9 | 184 | 25 | 2 | 0 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-99 | 1573 | 1101 | 608 | 30 | 169 | 5 | 181 | 35 | 2 | 0 |

| Molecule | HOMO (eV) | LUMO (eV) | Gap (eV) | Dipole (D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MZB | −6.76 | −0.81 | 5.95 | 6.43 |

| MZBMOD-77 | −5.95 | −0.35 | 5.60 | 2.72 |

| MZBMOD-79 | −6.80 | −1.57 | 5.23 | 8.26 |

| MZBMOD-93 | −6.17 | −1.24 | 4.92 | 2.91 |

| MZBMOD-50 | −6.52 | −0.95 | 5.57 | 1.58 |

| MZBMOD-99 | −6.41 | −1.08 | 5.33 | 7.88 |

| Complex | Average RMSD (nm) | Average RMSF (nm) | Average RoG (nm) | Average SASA (nm2) | Average Distance (nm) | Number of Hydrogen Bonds Between the Ligand-Receptor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSMB5 (Apo-protein) | 0.347 ± 0.015 | 0.078 ± 0.038 | 1.608 ± 0.014 | 104.064 ± 2.283 | N/A | N/A |

| PSMB5_MZB | 0.702 ± 0.174 | 0.093 ± 0.053 | 1.606 ± 0.009 | 102.644 ± 2.027 | 1.864 ± 0.429 | 1.863 ± 0.781 |

| PSMB5_BA | 1.226 ± 0.370 | 0.076 ± 0.034 | 1.620 ± 0.014 | 105.868 ± 2.528 | 2.317 ± 0.865 | 0.414 ± 0.751 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-77 | 0.396 ± 0.114 | 0.111 ± 0.064 | 1.606 ± 0.008 | 102.489 ± 1.770 | 1.303 ± 0.398 | 2.416 ± 0.864 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-79 | 0.419 ± 0.122 | 0.099 ± 0.051 | 1.594 ± 0.008 | 99.847 ± 1.980 | 1.523 ± 0.547 | 1.300 ± 0.720 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-93 | 1.146 ± 0.317 | 0.100 ± 0.061 | 1.609 ± 0.011 | 100.798 ± 2.267 | 2.018 ± 0.214 | 0.642 ± 0.536 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-50 | 0.624 ± 0.155 | 0.086 ± 0.036 | 1.613 ± 0.012 | 103.070 ± 2.320 | 1.741 ± 0.152 | 0.708 ± 1.025 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-99 | 0.711 ± 0.153 | 0.093 ± 0.047 | 1.596 ± 0.009 | 101.919 ± 2.242 | 1.821 ± 0.427 | 0.617 ± 0.807 |

| Complex | MM/PBSA Free Binding Energy ΔG_Binding (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| PSMB5_MZB | −6.26 ± 4.08 |

| PSMB5_BA | −5.60 ± 6.01 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-77 | −19.99 ± 4.75 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-79 | −18.79 ± 4.22 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-93 | −4.15 ± 2.75 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-50 | −11.00 ± 3.21 |

| PSMB5_MZBMOD-99 | −7.51 ± 3.38 |

| Parameter | MZB | MZBMOD-77 | MZBMOD-79 | MZBMOD-93 | MZBMOD-50 | MZBMOD-99 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (g/mol) | 313.78 | 481.58 | 407.50 | 335.39 | 359.42 | 363.45 |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| cLogP | 0.513 | 2.810 | 1.591 | 1.597 | 0.716 | 2.671 |

| Total Surface Area | 217.61 | 354.78 | 298.60 | 244.84 | 245.13 | 282.73 |

| Polar Surface Area (PSA) | 75.63 | 105.23 | 101.93 | 76.07 | 83.91 | 92.70 |

| Relative PSA | 0.278 | 0.257 | 0.280 | 0.256 | 0.268 | 0.261 |

| CYP Inhibitor | None | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | None | None | None |

| Mutagenic | Low | None | None | High | None | None |

| Tumorigenic | High | None | None | None | None | None |

| Reproductive Effective | High | None | None | None | None | None |

| Irritant | None | Low | None | High | None | High |

| Shape Index | 0.524 | 0.428 | 0.413 | 0.375 | 0.423 | 0.577 |

| Molecular Flexibility | 0.398 | 0.323 | 0.308 | 0.247 | 0.405 | 0.455 |

| Molecular Complexity | 0.930 | 0.963 | 0.893 | 0.845 | 0.948 | 0.838 |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) | 509.102 | 690.075 | 579.515 | 504.734 | 592.286 | 631.913 |

| Hydrophobic Component of SASA (FOSA) | 262.447 | 423.787 | 455.525 | 340.156 | 412.699 | 461.339 |

| Hydrophilic Component of SASA (FISA) | 120.387 | 86.831 | 94.686 | 105.606 | 141.693 | 156.493 |

| Percent Human Oral Absorption | 78.905 | 100.000 | 90.684 | 77.373 | 78.031 | 73.843 |

| QPlogHERG | −2.071 | −3.252 | −1.726 | −3.750 | −2.556 | −2.726 |

| QPPCaco | 336.704 | 1026.878 | 741.274 | 246.230 | 324.836 | 194.782 |

| QPlogBB | −0.494 | −0.397 | −0.497 | 0.079 | −0.886 | −1.258 |

| QPPMDCK | 868.818 | 759.945 | 631.349 | 120.321 | 208.185 | 146.808 |

| QPlogKp | −3.168 | −2.200 | −2.681 | −5.225 | −3.709 | −3.778 |

| QPlogKhsa | −0.867 | 0.105 | −0.211 | −0.080 | −0.750 | −0.525 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alotaiq, N.; Dermawan, D. From Deep-Sea Natural Product to Optimized Therapeutics: Computational Design of Marizomib Analogs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412159

Alotaiq N, Dermawan D. From Deep-Sea Natural Product to Optimized Therapeutics: Computational Design of Marizomib Analogs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412159

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlotaiq, Nasser, and Doni Dermawan. 2025. "From Deep-Sea Natural Product to Optimized Therapeutics: Computational Design of Marizomib Analogs" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412159

APA StyleAlotaiq, N., & Dermawan, D. (2025). From Deep-Sea Natural Product to Optimized Therapeutics: Computational Design of Marizomib Analogs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412159