1. Introduction

Chronic and hard-to-heal wounds remain a significant clinical challenge worldwide, often resulting from impaired cellular response, persistent inflammation, or microbial infection [

1]. Wound healing is a complex, non-linear process that involves overlapping stages of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling, which can be significantly influenced by both extrinsic and intrinsic factors, such as cytokines, growth factors, and oxidative stress. Interruptions or imbalances in these stages often lead to delayed healing or chronic wounds [

2]. Consequently, various strategies have been developed to accelerate and improve the healing process. Any choice of wound treatment strategy should take into account the development of bacterial resistance, which is important in the current post-antibiotic era. Treatment compliance should also be considered. Bifunctionality expressed by the selection of appropriate biopolymers and active compounds is an important procedure when developing effective and convenient solutions for wound healing.

Biopolymer-based materials have gained prominence in wound care because of their natural origin, biocompatibility, and capacity to mimic the extracellular matrix [

3]. Among them, chitosan is particularly attractive owing to its polycationic nature, which imparts antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, while also enabling its use as a versatile drug delivery platform [

4,

5]. Chitosan has already found applications in wound dressings, membranes, and foils, supporting skin regeneration and accelerating the closure of burns, ulcers, and postoperative wounds. Furthermore, chitosan blended with polyethylene oxide (PEO) significantly improves electrospinnability and enables the formation of continuous nanofibers, which can serve as three-dimensional scaffolds to support tissue regeneration [

6]. Electrospinning, based on the application of electrostatic forces, has emerged as a powerful technique to produce nanofibrous mats with high surface area, porosity, and tunable morphology, making them excellent candidates for biomedical applications [

7].

Biopolymer-based materials can be effectively enhanced with natural additives, including plant-derived extracts exhibiting multifunctional biological activity.

Centella asiatica is an excellent example of such an ingredient [

8,

9].

Centella asiatica, also known as Gotu kola, is a medicinal herb rich in pentacyclic triterpenoids, including asiaticoside, madecassoside, and madecassic acid, along with other constituents such as centellose and centelloside [

10]. Among them, asiaticoside is considered the major bioactive compound in aqueous extracts of

C. asiatica (CAE) and has been extensively applied in traditional and alternative medicine formulations. Various biological activities of asiaticoside have been reported, including inhibition of keratinocyte proliferation, induction of collagen synthesis, and suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine activity [

11,

12]. These effects highlight its therapeutic potential in modulating skin repair and regeneration.

The innovative aspect of this study lies in the combination of

C. asiatica extract with chitosan/PEO nanofibers obtained by electrospinning. While chitosan-based nanofibers are well recognized for their structural and antimicrobial properties, and

C. asiatica is widely known for its regenerative and anti-inflammatory potential [

9], few studies have explored their integration into a single multifunctional wound-healing system [

13,

14,

15]. Incorporating asiaticoside-rich extract into electrospun nanofibers not only enhances therapeutic potential but also allows for controlled release of bioactive compounds directly at the wound site, thus addressing the limitations of conventional formulations.

This study aims to develop and comprehensively characterize electrospun chitosan/PEO nanofibers loaded with Centella asiatica extract as a multifunctional wound-healing platform. The novelty of this work lies in integrating asiaticoside-rich phytochemicals with a hybrid CS/PEO nanofibrous matrix to achieve sustained release up to 7 days, which marks a significant improvement compared with our previously developed hydrogels and 3D-printed chitosan systems that released the extract within 24 h. By combining a natural bioactive extract with a biopolymer–synthetic polymer nanofiber scaffold, this study introduces a new approach to prolonged topical delivery of triterpenoid saponins and expands the therapeutic potential of electrospun wound dressings.

Compared with our previously developed Centella asiatica delivery platform, chitosan hydrogels [

13] and 3D-printed chitosan-based scaffolds [

14], the electrospun nanofiber system investigated in this work introduces a significant functional improvement. Both earlier systems provided rapid release of asiaticosides, with complete release occurring within approximately 24 h, which limits their applicability in chronic wound environments that require prolonged exposure to bioactive compounds. In contrast, the nanofiber matrix described here enables sustained asiaticoside release for up to 7 days, resulting from a combined diffusion–erosion mechanism. This extended release profile represents a substantial advancement over our earlier formulations and provides a clear rationale for developing a nanofibrous dressing as a novel dosage form. It is also worth noting that the developed nanofibers offer a completely different functional use compared to hydrogel and 3D-printed dressings. Nanofibers offer significantly improved comfort of use, eliminating abrasion and unwanted loss of the applied system due to its significantly greater thickness or viscosity.

2. Results and Discussion

The present study focused on the development of chitosan-based nanofibers incorporating Centella asiatica extract, with the aim of selecting the optimal extract concentration and polymer composition to achieve favorable physicochemical and biological properties. The combination of chitosan with polyethylene oxide (PEO) provided a stable and flexible polymeric matrix characterized by good rheological properties, enhanced water retention, and improved mechanical resistance. Importantly, the incorporation of natural bioactive compounds into such biopolymeric nanofibers is expected to reduce potential side effects while ensuring a controlled and sustained release profile, thereby supporting wound-healing applications.

The

Centella asiatica extract was prepared under previously optimized conditions (70% methanol, 70 °C, three ultrasonic extraction cycles of 60 min each), followed by freeze-drying [

13].

In the first stage, the influence of polymer composition on the electrospinning process was evaluated. Pure chitosan exhibits poor spinnability due to its high viscosity, limited chain entanglement, and strong intermolecular interactions, which hinder the formation of continuous and defect-free fibers [

16]. To overcome these limitations, polyethylene oxide (PEO) was incorporated as a co-polymer. PEO is a synthetic, water-soluble polymer with excellent electrospinnability, high molecular flexibility, and the ability to form uniform nanofibers [

17]. When blended with chitosan, PEO improves solution viscosity, enhances chain entanglement, and reduces electrostatic repulsion between chitosan’s polycationic groups. As a result, the addition of PEO facilitates stable jet formation during electrospinning and contributes to the production of continuous nanofibers with improved morphology and mechanical stability [

18].

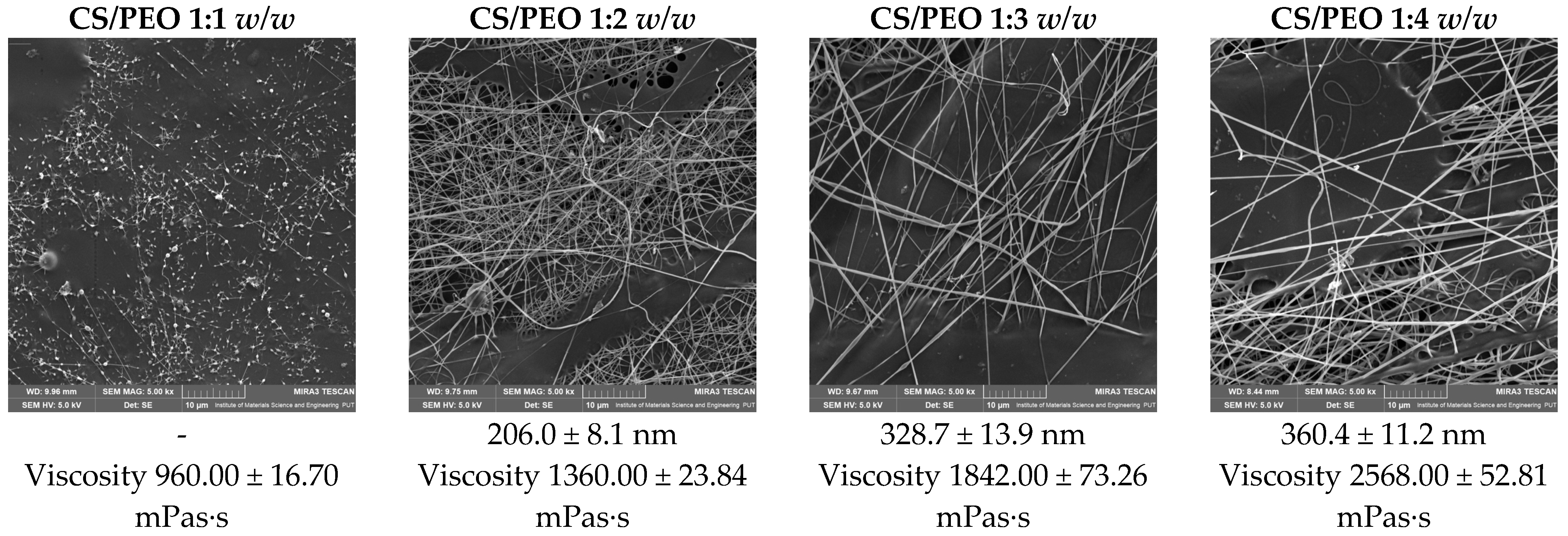

Figure 1 presents SEM micrographs of chitosan/PEO nanofibers obtained at different polymer ratios (CS/PEO = 1:1, 1:2, 1:3, and 1:4

w/w). Distinct differences in morphology and fiber diameter can be observed depending on the proportion of PEO. At the 1:1 ratio, the fibers exhibit morphological defects in the form of bead-like structures, indicating insufficient spinnability and reduced homogeneity of the material. Increasing the proportion of PEO results in the formation of smoother, more continuous nanofibers with higher uniformity. This improvement can be attributed to the enhanced chain entanglement and viscoelastic properties of the polymer solution. Quantitative analysis of fiber diameters confirmed that the average diameter increased with rising PEO content, ranging from 206.0 ± 80.5 nm at 1:2 to 360.4 ± 111.8 nm at 1:3 and 328.7 ± 139.5 nm at 1:4. These results demonstrate that the addition of PEO significantly influences nanofiber morphology, with the CS/PEO 1:2 and 1:3 systems exhibiting the most favorable structural properties for further functionalization. This also highlights the essential role of PEO as a synthetic co-spinning polymer that enables the electroprocessing of the natural biopolymer chitosan; therefore, the final nanofiber matrix should be regarded as a hybrid system composed of both natural and synthetic polymers rather than a purely biopolymer-based material.

As shown by the viscosity values included in

Figure 1, increasing the PEO proportion leads to a progressive rise in solution viscosity, which directly improves chain entanglement and stabilizes jet formation during electrospinning. The viscosity values obtained for the CS/PEO systems fall within the range typically reported as suitable for stable electrospinning (approximately 100–3000 mPa·s), ensuring sufficient chain entanglement and jet continuity during fiber formation [

19].

Several studies have confirmed that PEO content directly influences nanofiber morphology and diameter. Szymańska et al. reported that chitosan/PEO mats in a 1:4 ratio yielded nanofibers with an average diameter of 266 ± 114 nm, highlighting the stabilizing role of PEO in electrospinning and its impact on drug release profiles [

20]. Similarly, Liu et al. demonstrated that blends containing equal proportions of chitosan and PEO produced smooth and homogeneous nanofibers with diameters of 53.93 ± 17.07 nm [

21], while Murillo et al. obtained fibers of 124 ± 36 nm using a CS/PEO 1:1 system [

22]. These findings indicate that increasing PEO concentration generally results in larger fiber diameters and reduced bead formation, improving fiber homogeneity and mechanical stability. Collectively, the literature evidence confirms that the presence of PEO is crucial for achieving defect-free chitosan nanofibers, while its proportion enables tuning of fiber diameter and structural features depending on the intended biomedical application.

In the second stage of the study, the

Centella asiatica extract was incorporated into the selected hydrogel bases at concentrations of 1%, 2%, and 3% (

w/w). The objective was to evaluate how the increasing extract content influences the morphology and homogeneity of the obtained nanofibers. SEM analysis confirmed that the addition of the extract affected both the structural integrity and the diameter of the fibers.

Figure 2 presents SEM micrographs of CS/PEO nanofibers (ratios 1:2 and 1:3

w/w) loaded with varying concentrations of the extract. At a concentration of 1%, the nanofibers maintained good continuity and uniform morphology, with diameters ranging between ~444 nm and ~589 nm, depending on the polymer ratio. However, higher extract concentrations (2% and 3%) resulted in a progressive increase in average fiber diameter (up to ~893 nm in CS/PEO 1:3 with 3% extract) and reduced homogeneity, as evidenced by the appearance of irregularities and bead-like structures. This effect can be attributed to changes in the viscosity and conductivity of the polymer solution, which disrupts the stability of the electrospinning jet. Taken together, the results demonstrate that moderate extract loading (1%) is most favorable for obtaining uniform and defect-free nanofibers, while higher concentrations compromise fiber quality. These findings suggest that polymer–extract interactions and solution parameters must be carefully balanced to optimize the electrospinning process and produce nanofibers with desirable morphological features.

So, for all subsequent experiments, the CS/PEO (1:2 w/w) nanofibers containing 1% Centella asiatica extract were selected as the optimal formulation and used for further analyses.

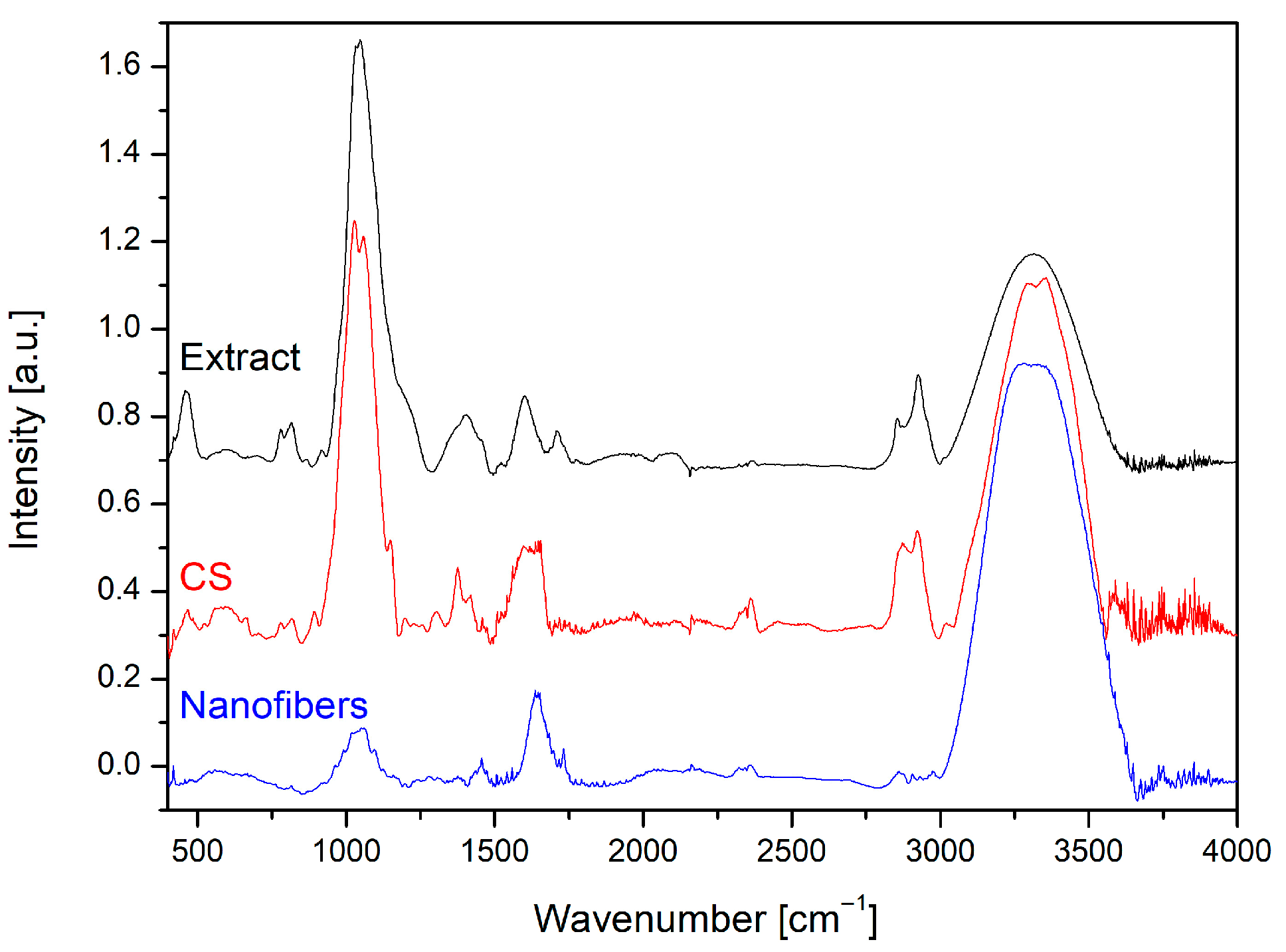

The FTIR spectra of

Centella asiatica extract and chitosan have been previously described in detail [

13,

14], and the characteristic bands corresponding to asiaticoside and CS were confirmed in nanofiber samples. Importantly, in the spectra of the composite nanofibers, no new absorption peaks were observed (

Figure 3), only shifts and overlapping of the characteristic bands. In addition to the signals originating from chitosan and the extract, the spectrum also contained dominant PEO-related bands, particularly the strong C–O–C stretching vibration at ~1100 cm

−1, as well as the CH

2 stretching bands at ~2880–2930 cm

−1 and the CH

2 rocking vibration near 840–950 cm

−1, which are typical for polyethylene oxide [

23]. The most noticeable changes were small shifts and broadening within the O–H/N–H stretching region around 3350–3300 cm

−1, characteristic of hydroxyl and amine groups, indicating stronger hydrogen bonding between the extract and the CS/PEO matrix. In addition, the amide I (C=O stretching) band of chitosan at ~1640 cm

−1 and the amide II (N–H bending) band near ~1580 cm

−1 partially overlapped with the asiaticoside carbonyl band at ~1730–1720 cm

−1. Overlapping and broadening of the C–O–C asymmetric stretching (~1150 cm

−1) and C–O stretching of secondary alcohols (~1060–1050 cm

−1) reflected contributions from both the polysaccharide backbone of chitosan and the glycosidic structure of asiaticoside, in addition to the strong ether bands of PEO. This overall pattern confirms that the components interact through physical interactions, mainly hydrogen bonding, rather than forming new covalent bonds, allowing the nanofibers to preserve the structural integrity and bioactivity of the incorporated extract.

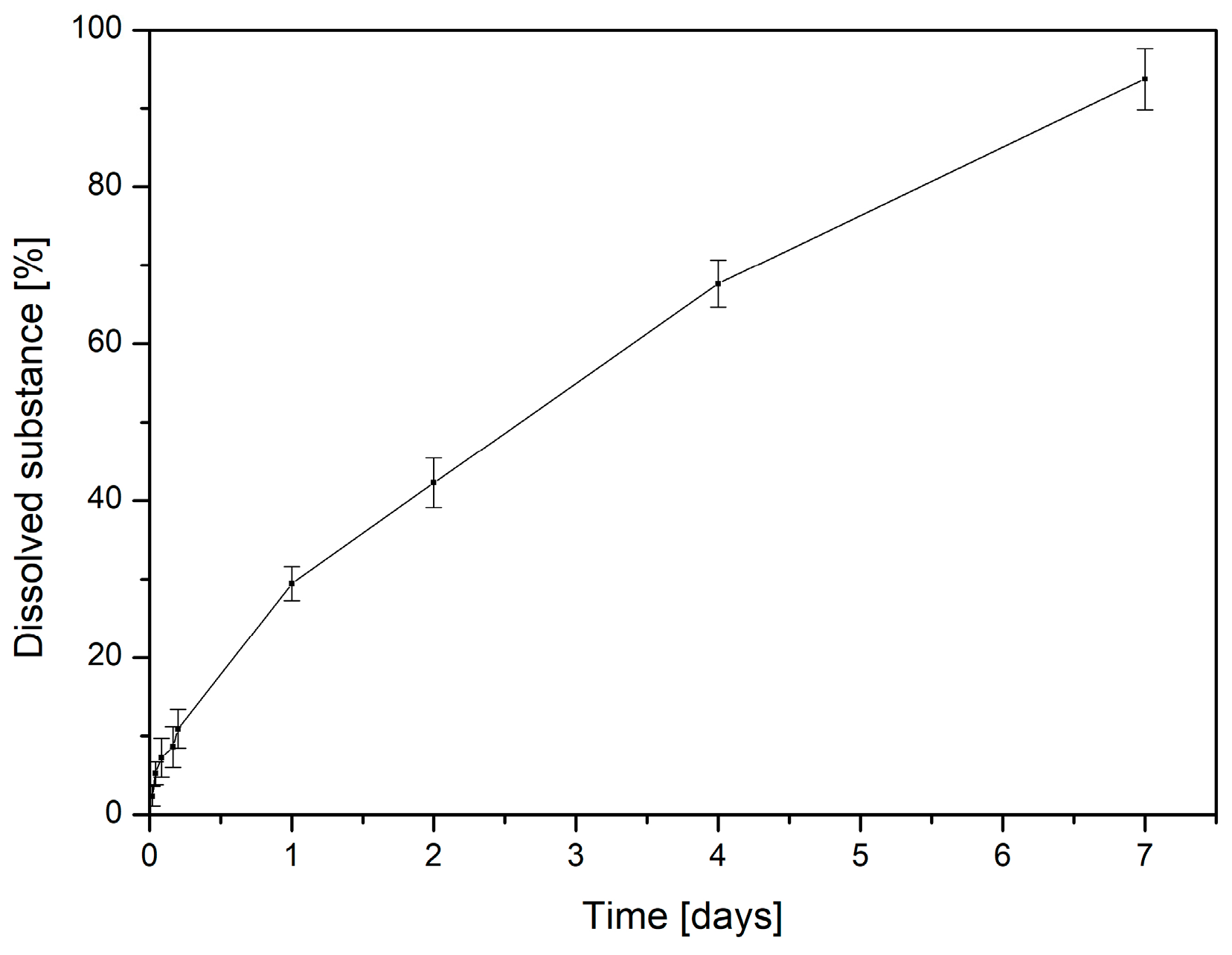

For a formulation to exert its therapeutic effect, it must ensure the efficient release of incorporated bioactive compounds. In this study, the in vitro release of asiaticosides from CS/PEO (1:2

w/w) nanofibers loaded with

Centella asiatica (1%) was analyzed using common kinetic models (zero-order, first-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer–Peppas, and Hixson–Crowell) (

Figure 4,

Table S1 in Supplementary Materials). As shown in

Table 1 and

Figure 4, the dataset is best described by the Hixson–Crowell cube-root model (highest R

2), indicating that release is governed by changes in the effective surface area/geometry of the matrix rather than by simple diffusion alone. The Higuchi model also provides an excellent description, supporting a diffusion-controlled component at early and intermediate times. The Korsmeyer–Peppas analysis (log–log linearization) yields an exponent n typical of anomalous (non-Fickian) transport, consistent with a combined mechanism in which diffusion from the hydrated polymer network is coupled with matrix relaxation/erosion. Zero-order and first-order descriptions are less adequate for this system.

To gain deeper insight into the release mechanism, the dissolution profile was analyzed using the Peppas–Sahlin model [

24]. First, the Korsmeyer–Peppas equation was fitted to the early stage of release (≤60% of drug released), and the kinetic exponent

was calculated from the slope of the log–log plot of

versus

. The obtained value of

indicated a non-Fickian transport regime. The value of

in the Peppas–Sahlin equation was therefore fixed to

, and the two model constants (

and

) were determined by linear regression. The coefficient

describes the contribution of Fickian diffusion, whereas

reflects the relaxation-(or erosion-) driven transport. The fitted model showed excellent agreement with the experimental data (R

2 close to 1), confirming the suitability of the Peppas–Sahlin approach for this formulation. Positive values of both constants indicated that both mechanisms participated in the release process. However,

was higher than

, and the ratio

remained below 1 over the whole-time interval, suggesting that Fickian diffusion was the predominant mechanism. The simulated contributions further confirmed that the diffusion term

dominated especially at shorter release times, while the relaxation component

increased gradually with time. These results indicate that the drug is released mainly by diffusion through the hydrated polymeric matrix, while polymer relaxation becomes more relevant at later stages.

Mechanistically, this behavior is consistent with gradual hydration and swelling of the CS/PEO network [

25]. In the release medium at pH 5.5, PEO, as a highly water-soluble polymer, dissolves rapidly, leading to an initial loss of mass and contributing to the early-stage burst release and erosion of the nanofiber surface. In contrast, chitosan undergoes gradual hydration, protonation, and swelling, forming a more stable but progressively loosening network. Therefore, the release profile likely reflects a two-step process in which the rapid dissolution of PEO governs the initial phase, while the subsequent swelling and partial erosion of chitosan sustain the later stages of asiaticoside release. This behavior is consistent with the strong fit of the Hixson–Crowell model, which accounts for geometry changes, and with the mixed diffusion–relaxation mechanism indicated by the Korsmeyer–Peppas and Peppas–Sahlin analyses. Such a multi-stage, geometry-affected process is advantageous for wound-care applications, where prolonged exposure to triterpenoid saponins supports ongoing antioxidant and anti-inflammatory action at the wound bed. This behavior is particularly advantageous in wound-healing applications, where prolonged availability of active compounds is desirable to ensure continuous support for tissue regeneration and protection against oxidative and inflammatory damage [

26].

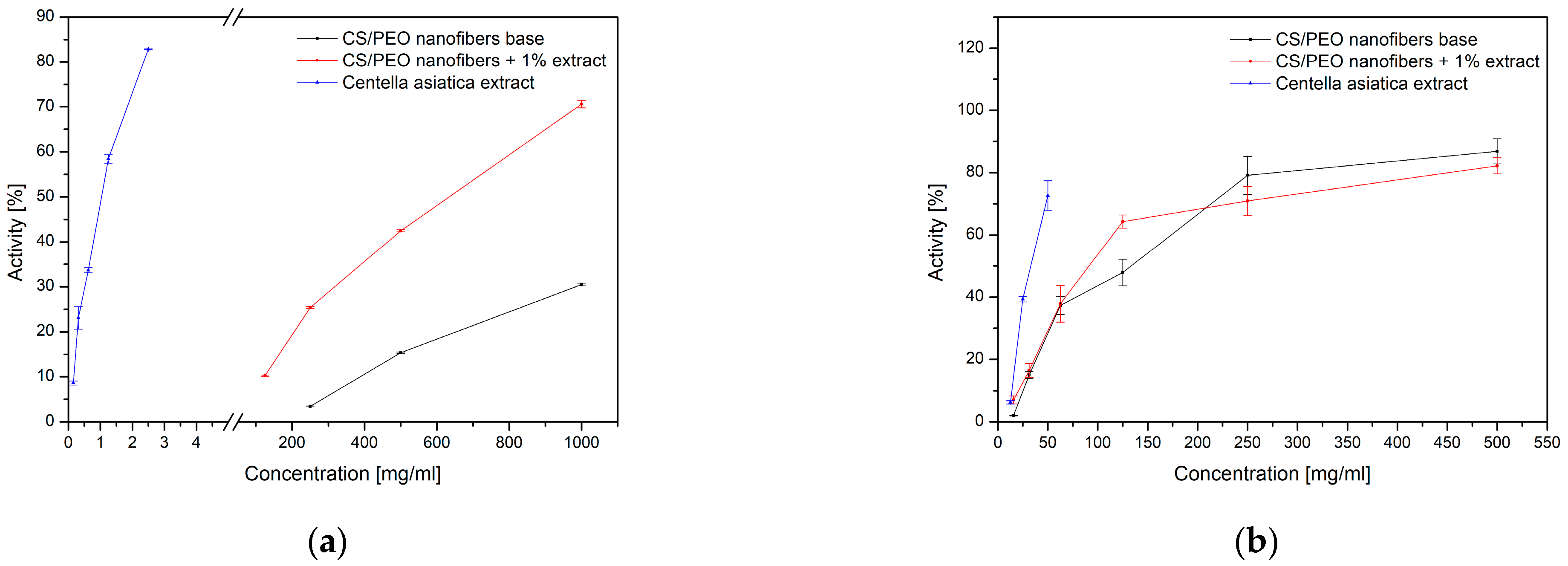

The biological activity of the obtained nanofibers was assessed in terms of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (

Figure 5,

Table 2). The base CS/PEO (1:2

w/w) system exhibited only moderate antioxidant potential, whereas the incorporation of

Centella asiatica extract significantly enhanced radical scavenging capacity. The comparison with the extract alone suggests that although the polymer matrix may limit the immediate availability of active compounds, it provides stabilization and controlled release, resulting in improved overall antioxidant performance. The sustained release profile of asiaticosides from the nanofiber matrix directly contributes to the prolonged antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity observed in vitro. Unlike the free extract, which provides rapid but transient bioactivity, the controlled release from the CS/PEO nanofibers ensures continuous availability of triterpenoid saponins over time. This release-driven exposure likely underlies the enhanced and more stable inhibition of DPPH radicals and hyaluronidase activity, highlighting the functional advantage of the nanofibrous delivery system over conventional formulations.

A similar tendency was observed for anti-inflammatory activity evaluated through hyaluronidase inhibition (

Table 2). While the extract alone showed only weak inhibition, the nanofiber formulation containing

Centella asiatica displayed markedly stronger effects. Notably, even the CS/PEO base demonstrated measurable inhibition, confirming the intrinsic bioactivity of chitosan. These findings indicate a synergistic effect between the natural extract and the chitosan-based carrier, which not only enhances antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties but also supports the potential of the developed nanofibers as multifunctional biomaterials for wound-healing applications.

The enhanced activity observed for the composite system is consistent with the pharmacological properties of

C. asiatica triterpenoid saponins, such as asiaticoside and madecassoside. These compounds act as direct radical scavengers and modulate cellular responses by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) and promoting fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis [

10]. At the same time, the inhibitory effect of chitosan on hyaluronidase activity can be attributed to several complementary mechanisms. As a polycationic biopolymer, chitosan possesses protonated amino groups that can interact electrostatically with negatively charged residues of the enzyme and with hyaluronic acid, thereby hindering substrate access to the catalytic site [

27]. Furthermore, the formation of dense polymeric matrices, such as nanofibers or hydrogels, provides a physical diffusion barrier that restricts the penetration of hyaluronic acid to the enzyme [

28]. Chitosan has also been reported to immobilize enzymes on its surface through ionic and hydrogen bonding, which reduces their catalytic mobility and overall enzymatic efficiency [

29]. The synergistic effect observed in our study reflects these complementary mechanisms. Similar findings were reported by Phupaisan et al., who demonstrated improved anti-hyaluronidase activity when

C. asiatica was combined with other antioxidants [

30], and by Paczkowska-Walendowska et al., who showed that chitosan scaffolds enriched with baicalein-rich extracts enhanced both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential [

31].

The antimicrobial potential of the obtained nanofibers was evaluated against representative Gram-positive (

Staphylococcus aureus), Gram-negative (

Klebsiella pneumoniae), and fungal (

Candida albicans) strains (

Table 3). These microorganisms were selected as clinically relevant models because they are among the most common pathogens associated with skin and soft tissue infections as well as chronic wound colonization.

S. aureus is a leading cause of wound infections, known for its ability to form biofilms and secrete toxins that impair tissue healing [

32].

K. pneumoniae, a Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen, is increasingly associated with multidrug-resistant wound infections, where it exacerbates inflammation and delays regeneration [

33]. While

C. albicans represents fungal pathogens frequently isolated from chronic wounds, its capacity to adhere, form biofilms, and secrete hydrolytic enzymes contributes to persistent infection and impaired tissue repair [

34]. The CS/PEO nanofiber base demonstrated the strongest activity, particularly against

S. aureus and

K. pneumoniae, with low minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs). In contrast, the extract-loaded nanofibers exhibited weaker antimicrobial effects, and the

C. asiatica extract alone showed negligible activity within the tested concentration range. These results suggest that the antimicrobial effect is mainly attributed to the chitosan component, while the incorporation of the plant extract may dilute or partially mask this activity. These observations clearly indicate that the antimicrobial properties of the nanofiber system are primarily derived from the chitosan component. Chitosan is well known for its broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties, which result from its polycationic nature. The positively charged amino groups interact with negatively charged bacterial membranes, leading to increased permeability, leakage of intracellular constituents, and ultimately cell death [

35]. Additionally, chitosan can chelate essential metal ions and bind to microbial DNA, further impairing microbial metabolism and replication [

36]. This explains the pronounced antibacterial activity of the nanofiber base observed in our study. The reduced antimicrobial activity of the extract-loaded nanofibers compared to the CS/PEO base can be attributed to several factors. Incorporation of the C. asiatica extract likely results in partial coating of the chitosan surface and masking of its protonated –NH

3+ groups, thereby limiting the electrostatic interactions responsible for membrane disruption in bacteria. In addition, the extract modifies fiber morphology and increases fiber diameter, which reduces the effective surface area of chitosan available for antimicrobial action. These combined effects explain the higher MIC values observed for the composite formulation. Previous studies have similarly demonstrated that combining

C. asiatica with other bioactive agents often requires optimization to balance wound-healing benefits with antimicrobial protection [

13].

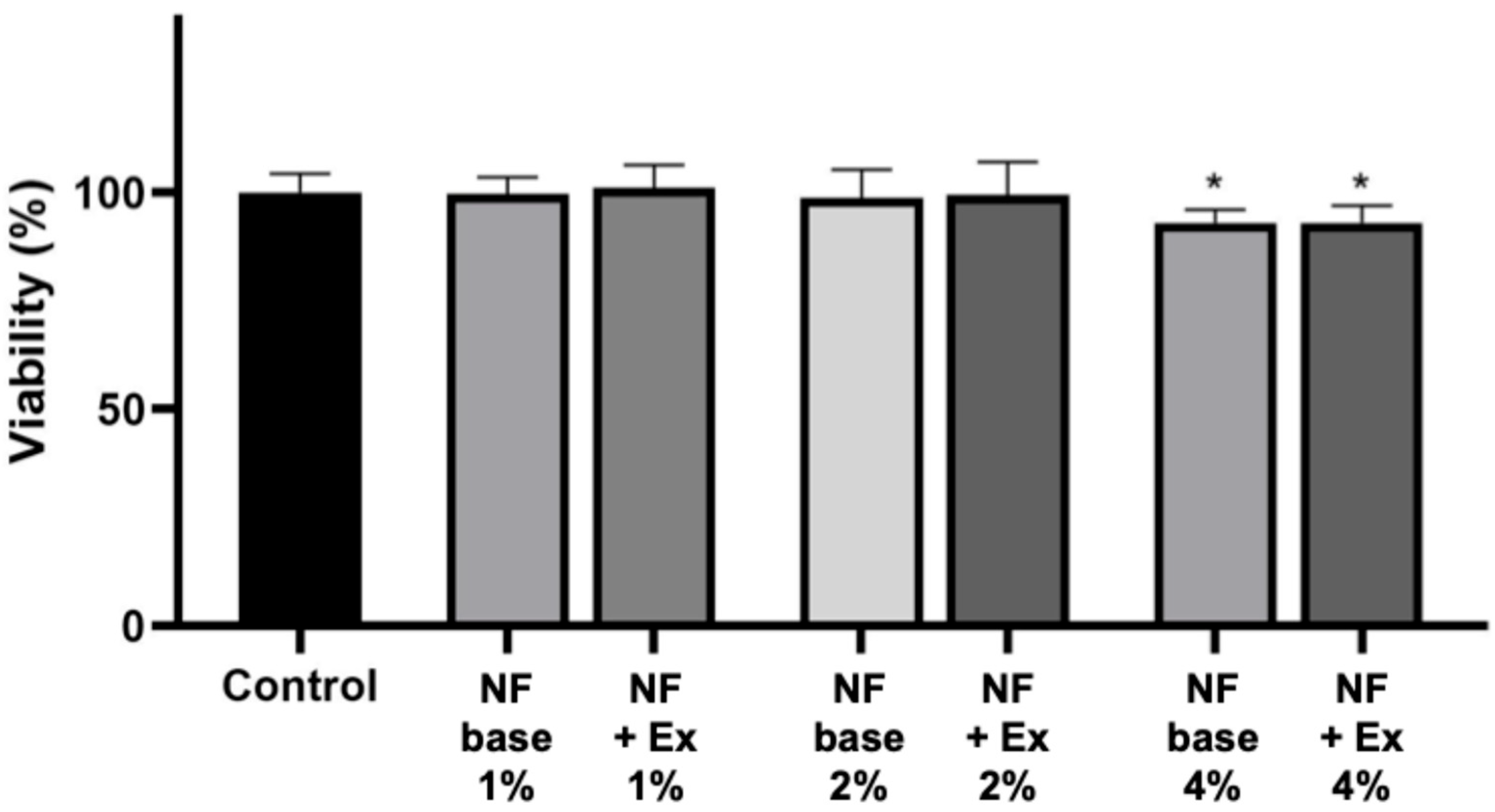

Biocompatibility of nanofibers was evaluated using human skin fibroblasts, and the results are presented in

Figure 6. Both the CS/PEO base and the extract-loaded nanofibers maintained high cell viability, comparable to the untreated control. No cytotoxic effects were observed, indicating that the developed nanofibers are well tolerated by fibroblasts. Interestingly, cells exposed to the extract-containing formulation showed slightly improved metabolic activity compared to the base, suggesting a potential stimulatory effect of

Centella asiatica constituents on fibroblast proliferation. These findings are consistent with previous reports demonstrating the favorable biocompatibility of chitosan-based nanofibers and the regenerative potential of

C. asiatica extract in wound-healing models [

13,

14]. The results confirm that the obtained nanofibers are suitable for biomedical use, particularly in wound dressings where cytocompatibility is a prerequisite for clinical application.

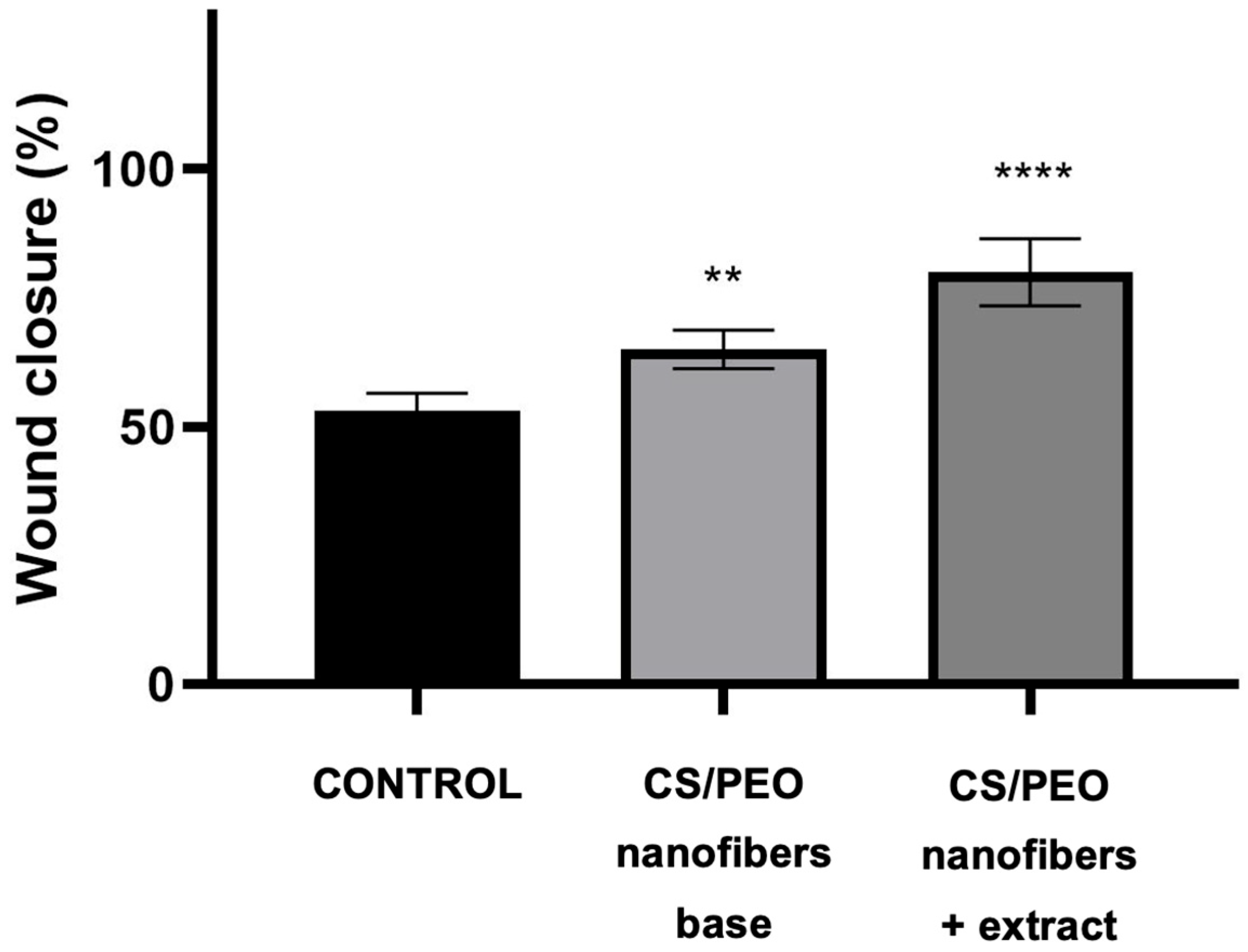

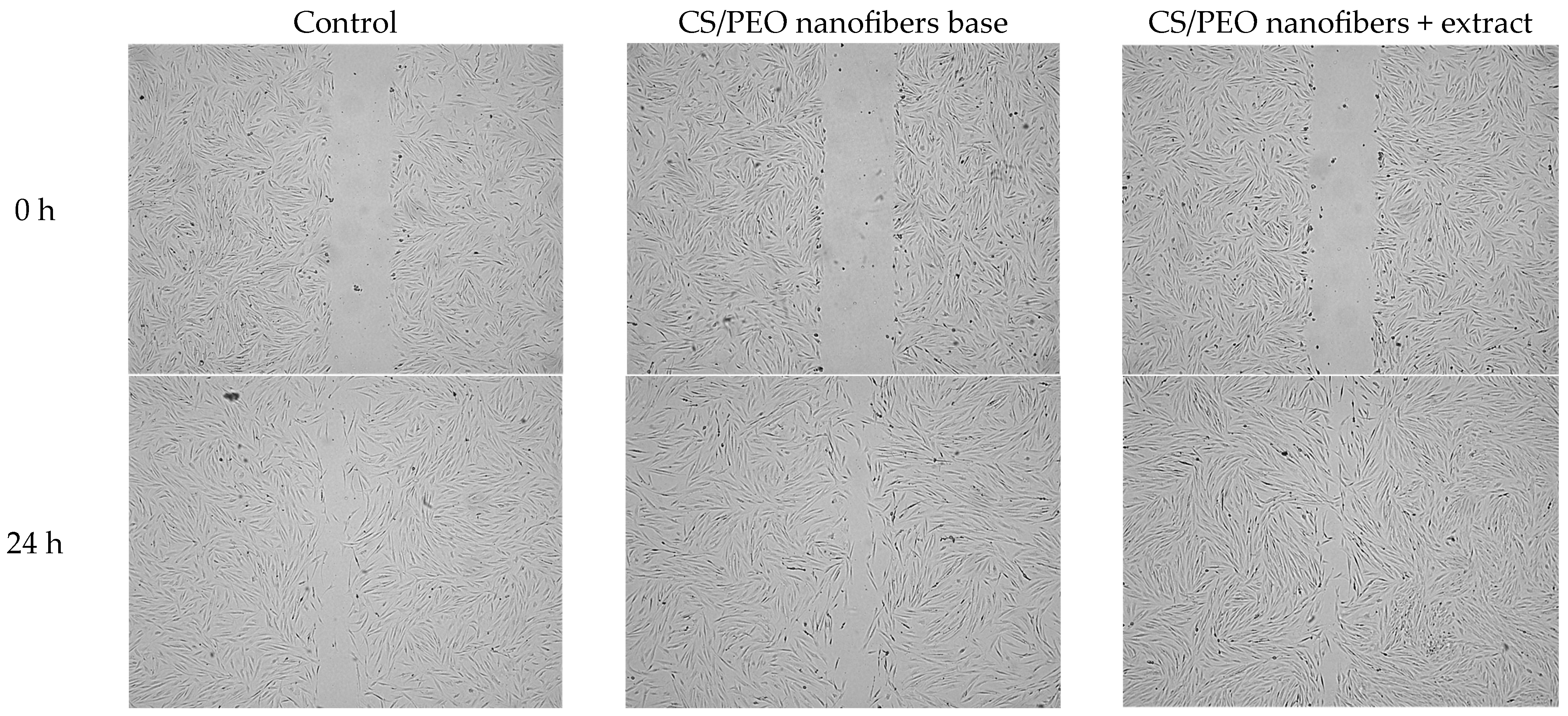

The wound-healing potential of the developed nanofibers was further evaluated using a scratch assay in human skin fibroblasts (Hs27). As shown in

Figure 7, cells treated with the extract-loaded nanofibers demonstrated significantly faster wound closure compared to both the untreated control and the chitosan/PEO base. Already after 24 h, nanofibers exhibited markedly reduced scratch width, indicating combined effects of enhanced fibroblast migration and proliferation. In contrast, the base formulation promoted moderate closure, confirming the intrinsic stimulatory effect of chitosan on cell migration. Representative microscopic images presented in

Figure 8 illustrate these findings, showing more advanced wound closure in cultures treated with extract-containing nanofibers compared to control and base samples. This result highlights the synergistic role of

Centella asiatica triterpenoid saponins, known to stimulate fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, and angiogenesis, in combination with the bioactive chitosan carrier. Together, these effects support the potential of the developed nanofiber system as a bioactive wound dressing capable of accelerating tissue repair.

The enhanced wound closure observed in the scratch assay can be attributed to the combined effects of nanofiber architecture and sustained bioactive release. The high surface area and ECM-mimicking fibrous structure promote close cell–material interactions, facilitating fibroblast adhesion and migration. Simultaneously, the gradual release of Centella asiatica triterpenoids supports fibroblast proliferation and regenerative signaling. This synergistic interaction between material structure and biological activity explains the significantly faster wound closure achieved by the extract-loaded nanofibers compared to the polymer base and control.

The present nanofiber formulation provides several clear advantages over our previously reported delivery systems based on chitosan hydrogels and 3D-printed scaffolds. Most importantly, the nanofibers ensured sustained release of asiaticoside for up to 7 days, whereas both hydrogels [

13] and 3D-printed constructs [

14] exhibited complete release within 24 h. This difference results from the highly porous but slowly eroding electrospun matrix, which follows Hixson–Crowell and Higuchi kinetics. Prolonged release is particularly relevant in chronic wound management, where continuous exposure to triterpenoid saponins supports antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and pro-regenerative processes. Furthermore, the nanofibers demonstrated enhanced anti-inflammatory activity and promoted faster fibroblast migration compared to the earlier formulations, likely due to higher surface area and more intimate cell–material interactions. These improvements confirm that electrospinning provides a significantly more effective platform for long-term delivery of asiaticoside-rich extracts. For future applications, incorporation of additional antimicrobial agents (e.g., silver nanoparticles, essential oils, or synergistic phytochemicals) may further enhance the spectrum of antimicrobial protection without compromising the beneficial effects of

C. asiatica.

The presented solution of utilizing the therapeutic properties of Centella asiatica extract in wound healing through the use of a nanofiber matrix is an innovative approach that requires further research. Although, to our knowledge, this is the first report in this area of development, and although the developed CS/PEO nanofibers loaded with Centella asiatica extract demonstrated promising release characteristics and biological activity profiles, several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, key material properties essential for wound-dressing applications, such as mechanical parameters (tensile strength, Young’s modulus, elongation at break) in both dry and hydrated states, were not evaluated. Similarly, wet-state performance metrics, including swelling behavior, water-uptake capacity, and water vapor transmission rate, were not determined, limiting the ability to fully assess moisture-management functionality. Future work should include these analyses to strengthen the understanding of structure–property relationships and to more comprehensively validate the suitability of the nanofiber system as a wound-dressing material.

In accordance with the principles of biomaterials development, comprehensive in vitro characterization represents a critical prerequisite for subsequent in vivo studies. At this stage, the present work was intentionally designed as an in vitro proof-of-concept to establish structure–function–bioactivity relationships prior to animal testing.