Placental Barrier Breakdown Induced by Trypanosoma cruzi-Derived Exovesicles: A Role for MMP-2 and MMP-9 in Congenital Chagas Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

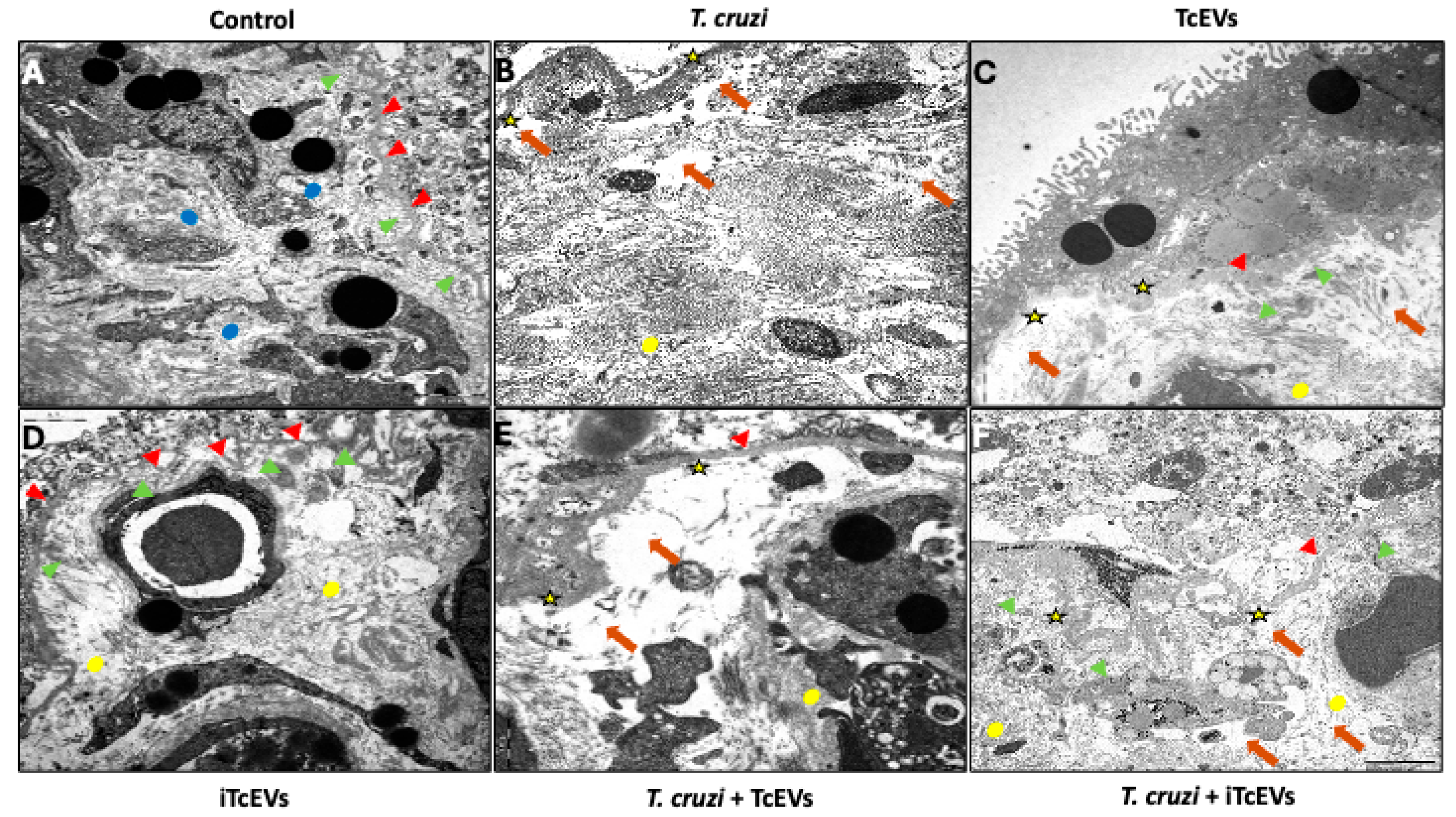

2.1. TcEVs Exacerbate Ultrastructural Damage to the Placental Barrier

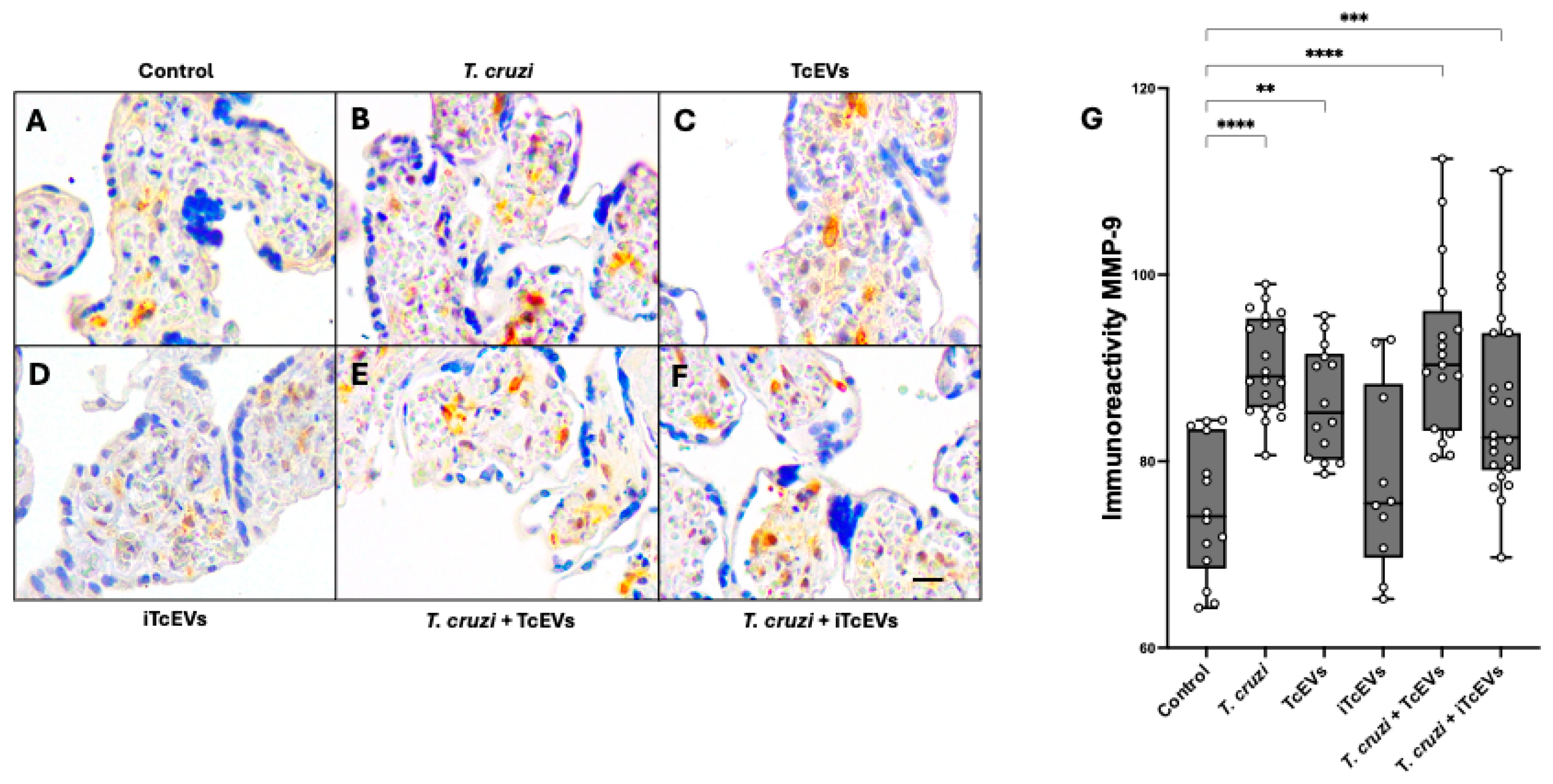

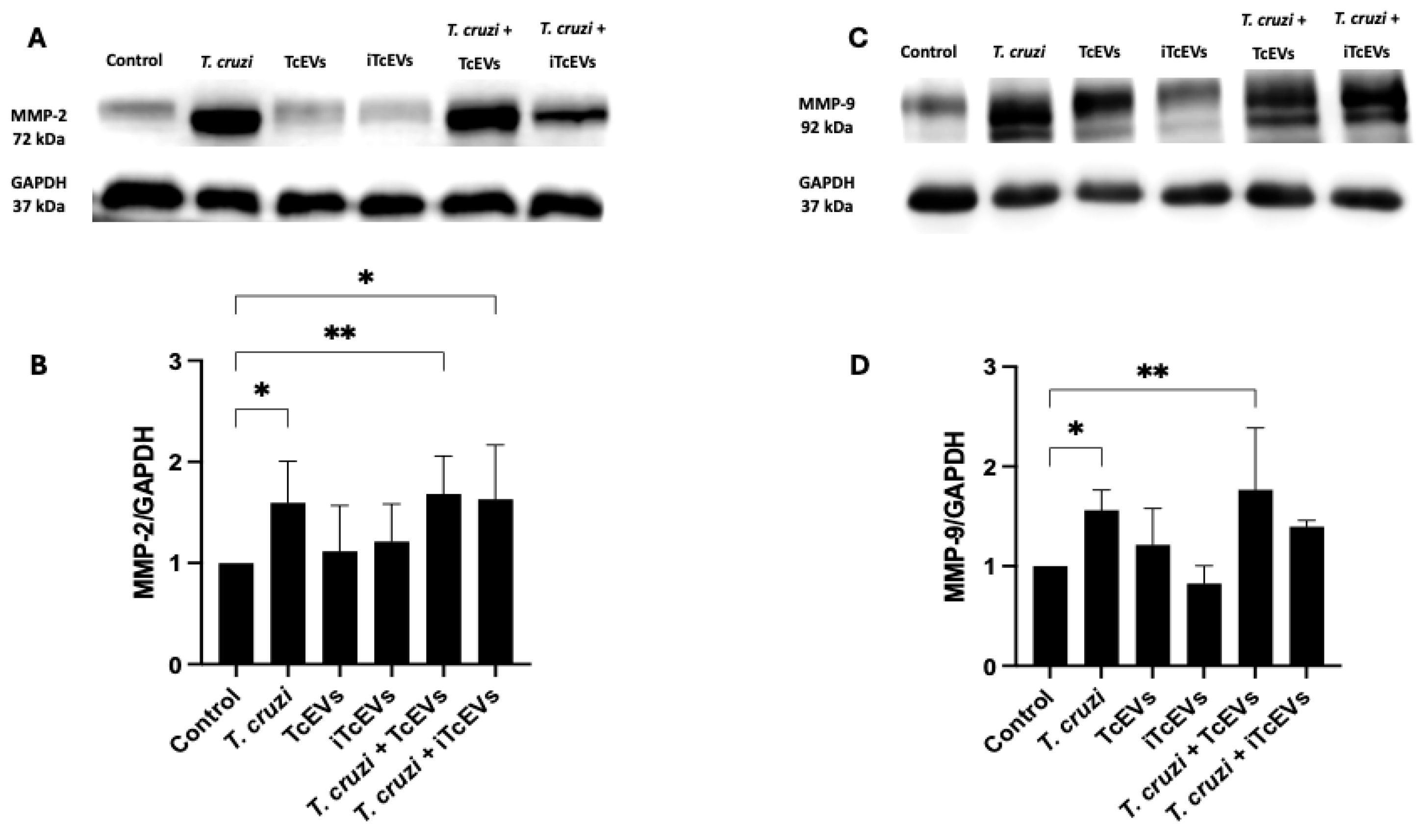

2.2. TcEVs per se Increase MMP-2 and MMP-9 Expression in the Villous Stroma

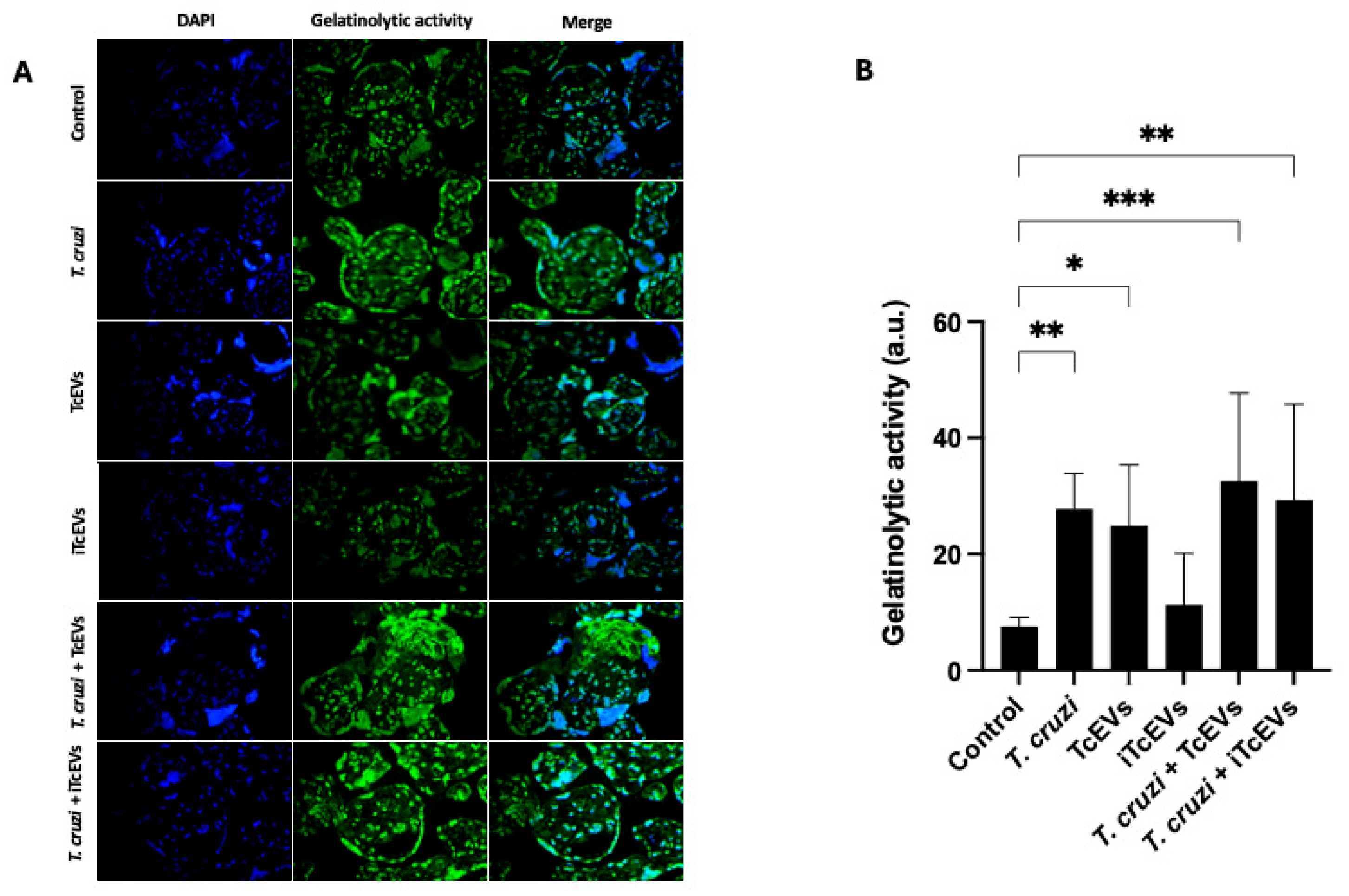

2.3. TcEVs Modulate Gelatinolytic Activity of Endogenous MMPs in HPEs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Parasite Culture and Harvesting

4.2. EV Isolation and Treatments

4.3. HPE Culture and Parasite Infection

4.4. Transmission Electron Microcopy

4.5. MMP Immunohistochemistry

4.6. MMP Detection by Western Blotting

4.7. Gelatin In Situ Zymography

4.8. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD | Chagas disease |

| T. cruzi | Trypanosoma cruzi |

| VS | Villous stroma |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| TcEVs | T. cruzi-derived extracellular vesicles |

| TS | Transialidase |

| MASPs | Mucin-associated Surface proteins |

| Cz | Cruzipain |

| HPEs | Human placental explants |

| MMP-2 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

| MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| iTcEVs | Heat-inactivated T. cruzi-derived extracellular vesicles |

| T. gondii | Toxoplasma gondii |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| IFBS | Inactivated fetal bovine serum |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PFS | Paraformaldehyde |

| DAB | Diaminobenzidine |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DL-BAPNA | Nα-Benzoyl-DL-arginine 4-nitroanilide hydrochloride |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase |

| ANOVA | ANalysis Of VAriance |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Castillo, C.; Liempi, A.; Fernàndez-Moya, A.; Guerrero-Muñoz, J.; Araneda, S.; Cáceres, G.; Alfaro, S.; Gallardo, C.H.; Maya, J.D.; Müller, M.; et al. Congenital Chagas Disease: The Importance of Trypanosoma cruzi-Placenta Interactions. Placenta 2025, S0143-4004(25)00011-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, Y.; Schijman, A.G.; Kemmerling, U. Placenta, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Congenital chagas Disease. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2020, 7, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Moya, A.; Oviedo, B.; Liempi, A.I.; Guerrero-Muñoz, J.; Rivas, C.; Arregui, R.; Araneda, S.; Cornet-Gomez, A.; Maya, J.D.; Müller, M.; et al. Trypanosoma cruzi-Derived Exovesicles Contribute to Parasite Infection, Tissue Damage, and Apoptotic Cell Death during Ex Vivo Infection of Human Placental Explants. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1437339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2023 Chagas Disease and RAISE Study Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Chagas Disease, 1990–2023: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.d.S.; Maldonado, R.A.; Farani, P.S.G. Chagas Disease in the 21st Century: Global Spread, Ecological Shifts, and Research Frontiers. Biology 2025, 14, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beatty, N.L.; Hamer, G.L.; Moreno-Peniche, B.; Mayes, B.; Hamer, S.A. Chagas Disease, an Endemic Disease in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 1691–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, E.; Xiong, X.; Carlier, Y.; Sosa-Estani, S.; Buekens, P. Frequency of the Congenital Transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2014, 121, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, M.K.; Rodríguez Aquino, M.S.; Buendía Rivas, C.A.; Landrove, A.M.; Portillo de Juarez, A.M.; Aguila Cerón, R.; García López, D.; Nolan, M.S. El Salvador Congenital Chagas team Prenatal Chagas Disease Screening in Latin America: The Current Policy Landscape and Potential Utility of an Expanded Maternal-Familial Trypanosoma cruzi Testing Framework. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2025, 47, 101139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marraffa, P.; Dentato, M.; Nurchis, M.C.; Angheben, A.; Olivo, L.; Barbera, G.; Damiani, G.; Gianino, M.M. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Screening for Congenital Chagas Disease in a Non-Endemic Area. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemmerling, U.; Osuna, A.; Schijman, A.G.A.G.; Truyens, C. Congenital Transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi: A Review About the Interactions Between the Parasite, the Placenta, the Maternal and the Fetal/Neonatal Immune Responses; Frontiers Media S.A.: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 10, p. 1854. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, C.; Chi, H.H.J.; Ghilardi, L.B.; Liempi, A.; Sato, M.N.; Kemmerling, U.; Bevilacqua, E. Placenta—A Competent, But Not Infallible, Antiviral and Antiparasitic Barrier. Reprod. Sci. 2025, 32, 2669–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, F.M. The Placenta as an Immunological Environment. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2025, 82, 14910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.H.; Stafford, L.S.; Langel, S.N. Advancing Protective Effects of Maternal Antibodies in Neonates through Animal Models. J. Immunol. 2025, 214, 2523–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorami-Sarvestani, S.; Vanaki, N.; Shojaeian, S.; Zarnani, K.; Stensballe, A.; Jeddi-Tehrani, M.; Zarnani, A.-H. Placenta: An Old Organ with New Functions. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1385762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.M. Genomics, the Diversification of Mammals, and the Evolution of Placentation. Dev. Biol. 2024, 516, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Pablos Torró, L.M.; Retana Moreira, L.; Osuna, A. Extracellular Vesicles in Chagas Disease: A New Passenger for an Old Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Luján, C.; Triquell, M.F.F.; Castillo, C.; Hardisson, D.; Kemmerling, U.; Fretes, R.E.E. Role of Placental Barrier Integrity in Infection by Trypanosoma cruzi. Acta Trop. 2016, 164, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, L.R.; Prescilla-Ledezma, A.; Cornet-Gomez, A.; Linares, F.; Jódar-Reyes, A.B.; Fernandez, J.; Vannucci, A.K.I.; De Pablos, L.M.; Osuna, A. Biophysical and Biochemical Comparison of Extracellular Vesicles Produced by Infective and Non-Infective Stages of Trypanosoma cruzi. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneghetti, P.; Kozela, E.; Alfandari, D.; Karam, P.A.; Porat, Z.; Xander, P.; Regev-Rudzki, N.; Schenkman, S.; Torrecilhas, A.C. Trypanosoma cruzi G and Y Strains’ Metacyclic Trypomastigote Sheds Extracellular Vesicles and Trigger Host-Cell Communication. Cell Biol. Int. 2025, 49, 1141–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiribao, M.L.; Díaz-Viraqué, F.; Libisch, M.G.; Batthyány, C.; Cunha, N.; De Souza, W.; Parodi-Talice, A.; Robello, C. Paracrine Signaling Mediated by the Cytosolic Tryparedoxin Peroxidase of Trypanosoma cruzi. Pathogens 2024, 13, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Serra, N.; Gualdron-Lopez, M.; Pinazo, M.-J.; Torrecilhas, A.C.; Fernandez-Becerra, C. Extracellular Vesicles in Trypanosoma cruzi Infection: Immunomodulatory Effects and Future Perspectives as Potential Control Tools against Chagas Disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 5230603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidel-Bar, R.; Agarwal, P. Outside Influences: The Impact of Extracellular Matrix Mechanics on Cell Migration. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2025, 164, 29–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.H.; Murphy, H.A.; Chapman, H.; George, E.M. Syncytialization Alters the Extracellular Matrix and Barrier Function of Placental Trophoblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 321, C694–C703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nappi, F. Structure and Function of the Extracellular Matrix in Normal and Pathological Conditions: Looking at the Bicuspid Aortic Valve. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, C.; López-Muñoz, R.A.; Duaso, J.; Galanti, N.; Jaña, F.; Ferreira, J.; Cabrera, G.; Maya, J.D.J.D.; Kemmerling, U. Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in Ex Vivo Trypanosoma cruzi Infection of Human Placental chorionic villi. Placenta 2012, 33, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-N.; Park, K.H.; Ahn, K.; Im, E.M.; Oh, E.; Cho, I. Extracellular Matrix-Related and Serine Protease Proteins in the Amniotic Fluid of Women with Early Preterm Labor: Association with Spontaneous Preterm Birth, Intra-Amniotic Inflammation, and Microbial Invasion of the Amniotic Cavity. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2023, 90, e13736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, K.; de Souza, L.J.; Salomão, N.G.; Machado, L.N.; Pereira, P.G.; Portari, E.A.; Basílio-de-Oliveira, R.; Dos Santos, F.B.; Neves, L.D.; Morgade, L.F.; et al. Zika Induces Human Placental Damage and Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, S.; Ozaki, Y.; Mori, R.; Ozawa, F.; Obayashi, Y.; Kitaori, T.; Sugiura-Ogasawara, M. MMP2 and MMP9 Are Associated with the Pathogenesis of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss through Protein Expression Rather than Genetic Polymorphism. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2024, 164, 104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karachrysafi, S.; Georgiou, P.; Kavvadas, D.; Papafotiou, F.; Isaakidou, S.; Grammatikakis, I.E.; Papamitsou, T. Immunohistochemical Study of MMP-2, MMP-9, EGFR and IL-8 in Decidual and Trophoblastic Specimens of Recurrent Pregnancy Loss Cases. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2023, 36, 2218523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lan, C.; Benlagha, K.; Camara, N.O.S.; Miller, H.; Kubo, M.; Heegaard, S.; Lee, P.; Yang, L.; Forsman, H.; et al. The Interaction of Innate Immune and Adaptive Immune System. Med. Comm. 2024, 5, e714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoo, R.; Nakimuli, A.; Vento-Tormo, R. Innate Immune Mechanisms to Protect Against Infection at the Human Decidual-Placental Interface. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creisher, P.S.; Klein, S.L. Pathogenesis of Viral Infections during Pregnancy. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e00073-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.F.S.; Botelho, R.M.; Fragoso, M.B.T.; Silva, M.L.; Xavier, J.A.; Borbely, A.U.; Goulart, M.O.F. Viral Vertical Transmission through the Placenta: The Potential of Natural Products as Therapeutic and Prophylactic Antiviral Agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, S.; Nebesna, Z.; Yakymchuk, Y.; Boychuk, A.; Shevchuk, O.; Korda, M.; Vari, S.G. Changes in Placentas of Pregnant Women Infected with COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, F.Y.; Cortez, C.; Izidoro, M.A.; Juliano, L.; Yoshida, N. Fibronectin-Degrading Activity of Trypanosoma cruzi Cysteine Proteinase Plays a Role in Host Cell Invasion. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 5166–5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira de Melo, A.C.; de Souza, E.P.; Elias, C.G.R.; dos Santos, A.L.S.; Branquinha, M.H.; d’Avila-Levy, C.M.; dos Reis, F.C.G.; Costa, T.F.R.; Lima, A.P.C.d.A.; de Souza Pereira, M.C.; et al. Detection of Matrix Metallopeptidase-9-like Proteins in Trypanosoma cruzi. Exp. Parasitol. 2010, 125, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunkofske, M.E.; Perumal, N.; White, B.; Strauch, E.-M.; Tarleton, R. Epitopes in the Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Attachment Signal Peptide of Trypanosoma cruzi Mucin Proteins Generate Robust but Delayed and Nonprotective CD8+ T Cell Responses. J. Immunol. 2023, 210, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe Costa, R.; da Silveira, J.F.; Bahia, D. Interactions between Trypanosoma cruzi Secreted Proteins and Host Cell Signaling Pathways. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharfstein, J. Subverting Bradykinin-Evoked Inflammation by Co-Opting the Contact System: Lessons from Survival Strategies of Trypanosoma cruzi. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2018, 25, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesías, A.C.; Vázquez, M.E.; Cosenza, M.; Poulakidas, S.N.; Ramos, F.; Acuña, L.; Pérez Brandán, C.; Tekiel, V.; Parodi, C. Strain-Dependent Immune Signaling by Small Extracellular Vesicles Derived From Trypanosoma cruzi-Infected Macrophages. Traffic 2025, 26, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gong, P.; Li, J. Trypanosoma Evansi Evades Host Innate Immunity by Releasing Extracellular Vesicles to Activate TLR2-AKT Signaling Pathway. Virulence 2021, 12, 2017–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.M.; Aronoff, D.M.; Eastman, A.J. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Preterm Prelabor Rupture of Membranes in the Setting of Chorioamnionitis: A Scoping Review. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2023, 89, e13642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Peng, X.; Ran, Y.; Feng, R.; Xia, Y.; Liu, Y. Transforming Growth Factor Alpha Promotes Bullous Pemphigoid Pathogenesis by Disrupting Cell Adhesion and Inducing Inflammation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.A.S.; Torrecilhas, A.C.; Souza, B.S.d.F.; Cruz, F.F.; Guedes, H.L.d.M.; Ramos, T.D.; Lopes-Pacheco, M.; Caruso-Neves, C.; Rocco, P.R.M. Potential of Extracellular Vesicles in the Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Therapy for Parasitic Diseases. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas-Pereira, L.; Menna-Barreto, R.; Lannes-Vieira, J. Extracellular Vesicles: Potential Role in Remote Signaling and Inflammation in Trypanosoma cruzi-Triggered Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 798054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestrini, M.M.A.; Alessio, G.D.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Teixeira-Carvalho, A. Extracellular Vesicles as Biomarkers Prognosis, Diagnosis, and Treatment in Chagas Disease. Curr. Top. Membr. 2025, 96, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, C.I.; Cronemberger-Andrade, A.; Souza-Melo, N.; Maricato, J.T.; Xander, P.; Batista, W.L.; Soares, R.P.; Schenkman, S.; Torrecilhas, A.C. Stress Induces Release of Extracellular Vesicles by Trypanosoma cruzi Trypomastigotes. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 2939693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, E.; Rojas, D.A.; Urbina, F.; Solari, A. The Oxidative Stress and Chronic Inflammatory Process in Chagas Disease: Role of Exosomes and Contributing Genetic Factors. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 4993452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, C.C.; Parker, L.L.; Lambert, J.A.; Baldwin, L.; Buxton, I.L.O.; Etezadi-Amoli, N.; Leblanc, N.; Burkin, H.R. Matrix Metallopeptidase 9 Promotes Contraction in Human Uterine Myometrium. Reprod. Sci. 2025, 32, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörg, A.; Grubert, T.; Grimm, T.; Guenzi, E.; Naschberger, E.; Samson, E.; Oostendorp, R.; Keller, U.; Stürzl, M. Maternal HIV Type 1 Infection Suppresses MMP-1 Expression in Endothelial Cells of Uninfected Newborns: Nonviral Vertical Transmission of HIV Type 1-Related Effects. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 2005, 21, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchide, N.; Obatake, K.; Yamada, R.; Sadanari, H.; Matsubara, K.; Murayama, T.; Ohyama, K. Regulation of Matrix Metalloproteinases-2 and -9 Gene Expression in Cultured Human Fetal Membrane Cells by Influenza Virus Infection. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 39, 1912–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pena-Burgos, E.M.; Regojo-Zapata, R.M.; Caballero-Ferrero, Á.; Martínez-Payo, C.; Viñuela-Benéitez, M.D.C.; Montero, D.; De La Calle, M. The Spectrum of Placental Findings of First-Trimester Cytomegalovirus Infection Related to the Presence of Symptoms in the Newborns and Stillbirths. Mod. Pathol. 2025, 38, 100808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liempi, A.; Castillo, C.; Medina, L.; Galanti, N.; Maya, J.D.; Parraguez, V.H.; Kemmerling, U. Comparative Ex Vivo Infection with Trypanosoma cruzi and Toxoplasma gondii of Human, Canine and Ovine Placenta: Analysis of Tissue Damage and Infection Efficiency. Parasitol. Int. 2020, 76, 102065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retana Moreira, L.; Rodríguez Serrano, F.; Osuna, A. Extracellular Vesicles of Trypanosoma cruzi Tissue-Culture Cell-Derived Trypomastigotes: Induction of Physiological Changes in Non-Parasitized Culture Cells. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pablos, L.M.; Díaz Lozano, I.M.; Jercic, M.I.; Quinzada, M.; Giménez, M.J.; Calabuig, E.; Espino, A.M.; Schijman, A.G.; Zulantay, I.; Apt, W.; et al. The C-Terminal Region of Trypanosoma cruzi MASPs Is Antigenic and Secreted via Exovesicles. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, G.G.; Madrid-Marina, V.; Martínez-Romero, A.; Torres-Poveda, K.; Favela-Hernández, J.M. Host-Pathogen Interaction Interface: Promising Candidate Targets for Vaccine-Induced Protective and Memory Immune Responses. Vaccines 2025, 13, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Bhat, C.V.; Sagilkumar, A.C.; Aziz, S.; Arya, J.; Dutta, A.; Dutta, S.; Show, S.; Sharma, K.; Rakshit, S.; et al. Bacterial Pore-Forming Toxin Pneumolysin Drives Pathogenicity through Host Extracellular Vesicles Released during Infection. iScience 2024, 27, 110589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara, B.; Sassot, M.; Calo, G.; Paparini, D.; Gliosca, L.; Chaufan, G.; Loureiro, I.; Vota, D.; Ramhorst, R.; Pérez Leirós, C.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles of Porphyromonas Gingivalis Disrupt Trophoblast Cell Interaction with Vascular and Immune Cells in an In Vitro Model of Early Placentation. Life 2023, 13, 1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schemiko Almeida, K.; Rossi, S.A.; Alves, L.R. RNA-Containing Extracellular Vesicles in Infection. RNA Biol. 2024, 21, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-El-Naga, I.F. Emerging Roles for Extracellular Vesicles in Schistosoma Infection. Acta Trop. 2022, 232, 106467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad-Rahimi, H.; Nemati, S.; Zanjirani-Farahani, L.; Mahdavi, F.; Mirjalali, H. The Increased Bax/Bcl-2 Ratio and Induced Apoptosis in Human Macrophages Treated by Echinococcus Granulosus Hydatid Cyst Fluid Extracellular Vesicles. BMC Res. Notes 2025, 18, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumbado-Salas, M.; Rojas, A.; Maizels, R.M.; Mora, J. Cross-Species Immunomodulation by Zoonotic Helminths: The Roles of Excretory/Secretory Products and Extracellular Vesicles. Curr. Top. Membr. 2025, 96, 47–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibrandi, S.; Clemens, A.; Li, Y.; Shufesky, W.J.; Vo, A.; Ammerman, N.; Huang, E.; Watkins, S.C.; Heeger, P.; Jordan, S.; et al. Exosome-Primed T Cell Immunity Is Facilitated by Complement Activation. Am. J. Transpl. 2025, S1600-6135(25)02988-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, C.; Diaz-Luján, C.; Liempi, A.; Fretes, R.E.; Kemmerling, U. Mammalian Placental Explants: A Tool for Studying Host-Parasite Interactions and Placental Biology. Placenta 2025, 166, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, R.P.; Meneghetti, P.; de Barros, L.A.; de Cassia Buck, P.; Mady, C.; Ianni, B.M.; Fernandez-Becerra, C.; Torrecilhas, A.C. Isolation and Molecular Characterization of Circulating Extracellular Vesicles from Blood of Chronic Chagas Disease Patients. Cell Biol. Int. 2022, 46, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassi, A.; Rassi, A.; Marcondes de Rezende, J. American Trypanosomiasis (Chagas Disease). Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 26, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fretes, R.E.R.; Kemmerling, U. Mechanism of Trypanosoma cruzi Placenta Invasion and Infection: The Use of Human chorionic villi Explants. J. Trop. Med. 2012, 2012, 614820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipes, D.P. Braunwald’s Heart Disease E-Book: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 978-0-323-55593-7. [Google Scholar]

- Villalta, F.; Kierszenbaum, F. Growth of Isolated Amastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi in Cell-Free Medium. J. Protozool. 1982, 29, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornet-Gomez, A.; Retana Moreira, L.; Kronenberger, T.; Osuna, A. Extracellular Vesicles of Trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi Induce Changes in Ubiquitin-Related Processes, Cell-Signaling Pathways and Apoptosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7618, Correction in Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duaso, J.; Rojo, G.; Cabrera, G.; Galanti, N.; Bosco, C.; Maya, J.D.J.D.; Morello, A.; Kemmerling, U. Trypanosoma cruzi Induces Tissue Disorganization and Destruction of chorionic villi in an Ex Vivo Infection Model of Human Placenta. Placenta 2010, 31, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Espinoza, M.J.; Mezzano, L.; Theumer, M.G.; Panzetta-Dutari, G.M.; Triquell, M.F.; Díaz-Luján, C.M.; Fretes, R.E. Participation of Kynurenine Pathway Metabolites in Trypanosoma cruzi Infection of Human Placenta. Placenta 2025, S0143-4004(25)00692-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buendía-Abad, M.; García-Palencia, P.; de Pablos, L.M.; Alunda, J.M.; Osuna, A.; Martín-Hernández, R.; Higes, M. First Description of Lotmaria passim and Crithidia mellificae Haptomonad Stages in the Honeybee Hindgut. Int. J. Parasitol. 2022, 52, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suvarna, S.K.; Layton, C.; Bancroft, J.D. Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques, 8th Edition; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 1–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadler-Olsen, E.; Kanapathippillai, P.; Berg, E.; Svineng, G.; Winberg, J.-O.; Uhlin-Hansen, L. Gelatin in Situ Zymography on Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Tissue: Zinc and Ethanol Fixation Preserve Enzyme Activity. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2010, 58, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fernández-Moya, A.; Liempi, A.; Müller, M.; Arregui, R.; Osuna, A.; Cornet-Gómez, A.; Castillo, C.; Kemmerling, U. Placental Barrier Breakdown Induced by Trypanosoma cruzi-Derived Exovesicles: A Role for MMP-2 and MMP-9 in Congenital Chagas Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412131

Fernández-Moya A, Liempi A, Müller M, Arregui R, Osuna A, Cornet-Gómez A, Castillo C, Kemmerling U. Placental Barrier Breakdown Induced by Trypanosoma cruzi-Derived Exovesicles: A Role for MMP-2 and MMP-9 in Congenital Chagas Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412131

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Moya, Alejandro, Ana Liempi, Marioly Müller, Rocío Arregui, Antonio Osuna, Alberto Cornet-Gómez, Christian Castillo, and Ulrike Kemmerling. 2025. "Placental Barrier Breakdown Induced by Trypanosoma cruzi-Derived Exovesicles: A Role for MMP-2 and MMP-9 in Congenital Chagas Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412131

APA StyleFernández-Moya, A., Liempi, A., Müller, M., Arregui, R., Osuna, A., Cornet-Gómez, A., Castillo, C., & Kemmerling, U. (2025). Placental Barrier Breakdown Induced by Trypanosoma cruzi-Derived Exovesicles: A Role for MMP-2 and MMP-9 in Congenital Chagas Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12131. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412131