Eco-Friendly Activation of Silicone Surfaces and Antimicrobial Coating with Chitosan Biopolymer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

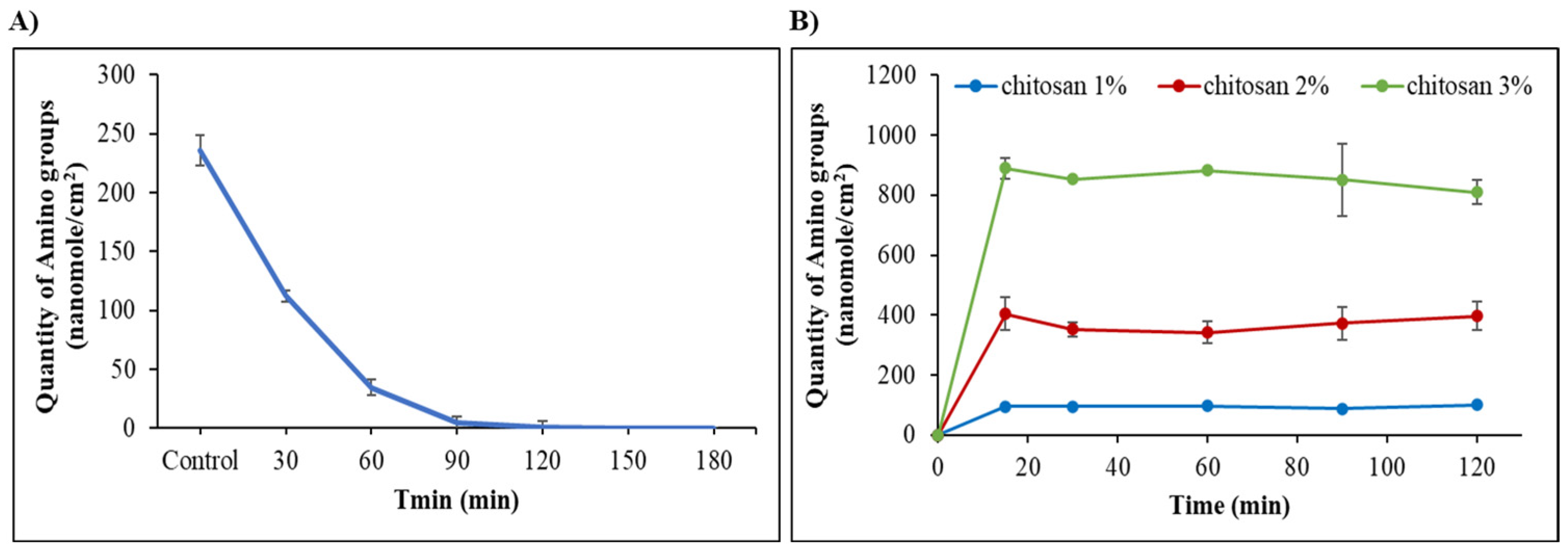

2.1. Surface Activation of Silicone by Reaction with Ethanolamine (ETA) or 1,3-Diaminopropane (DAP)

2.2. Silicone Modification with DAP, ETA, 3-Amino-1,2-Propanediol (APD), and Ethylenediamine (EDA)

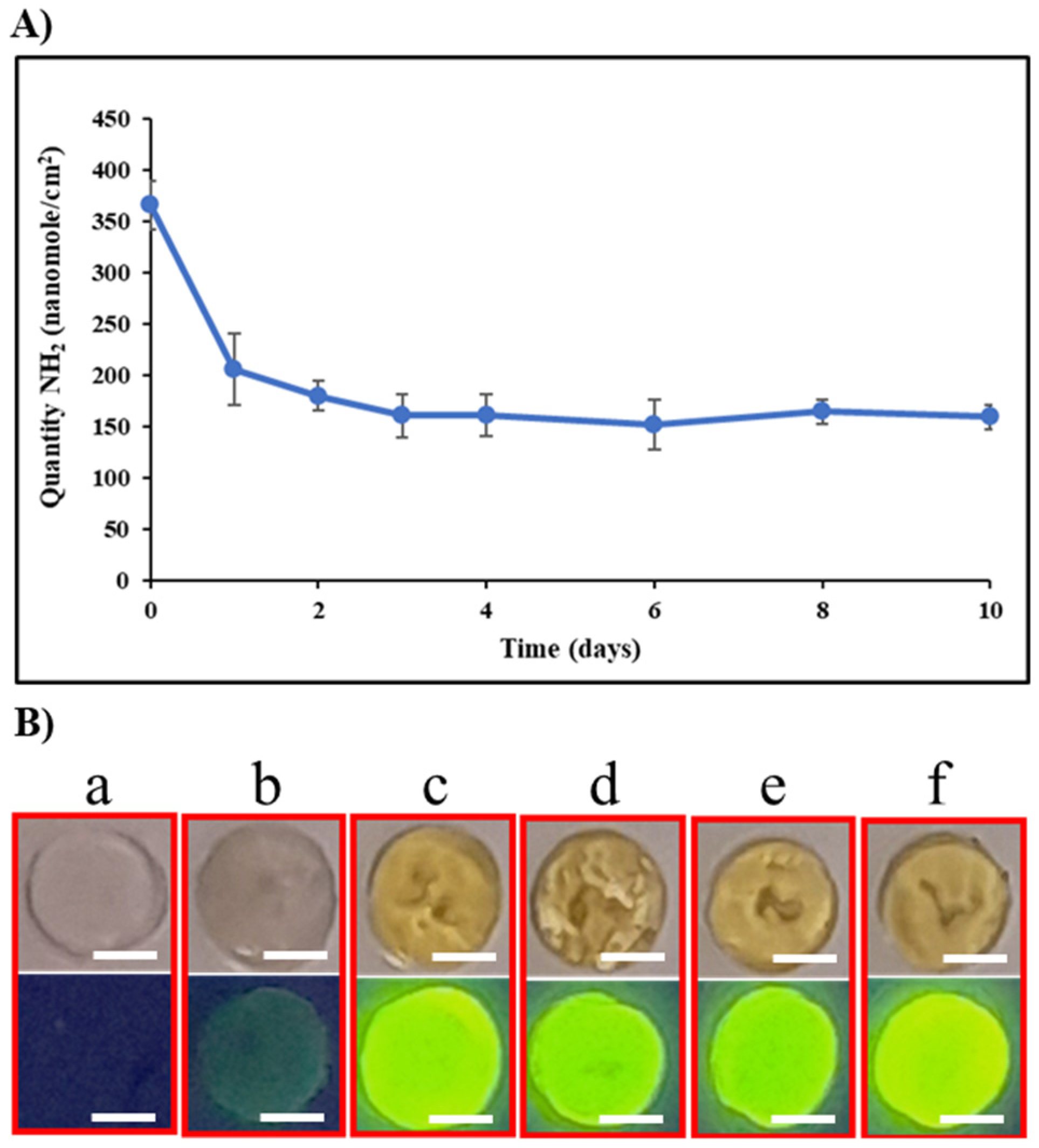

2.3. Stability of the Surface Activation

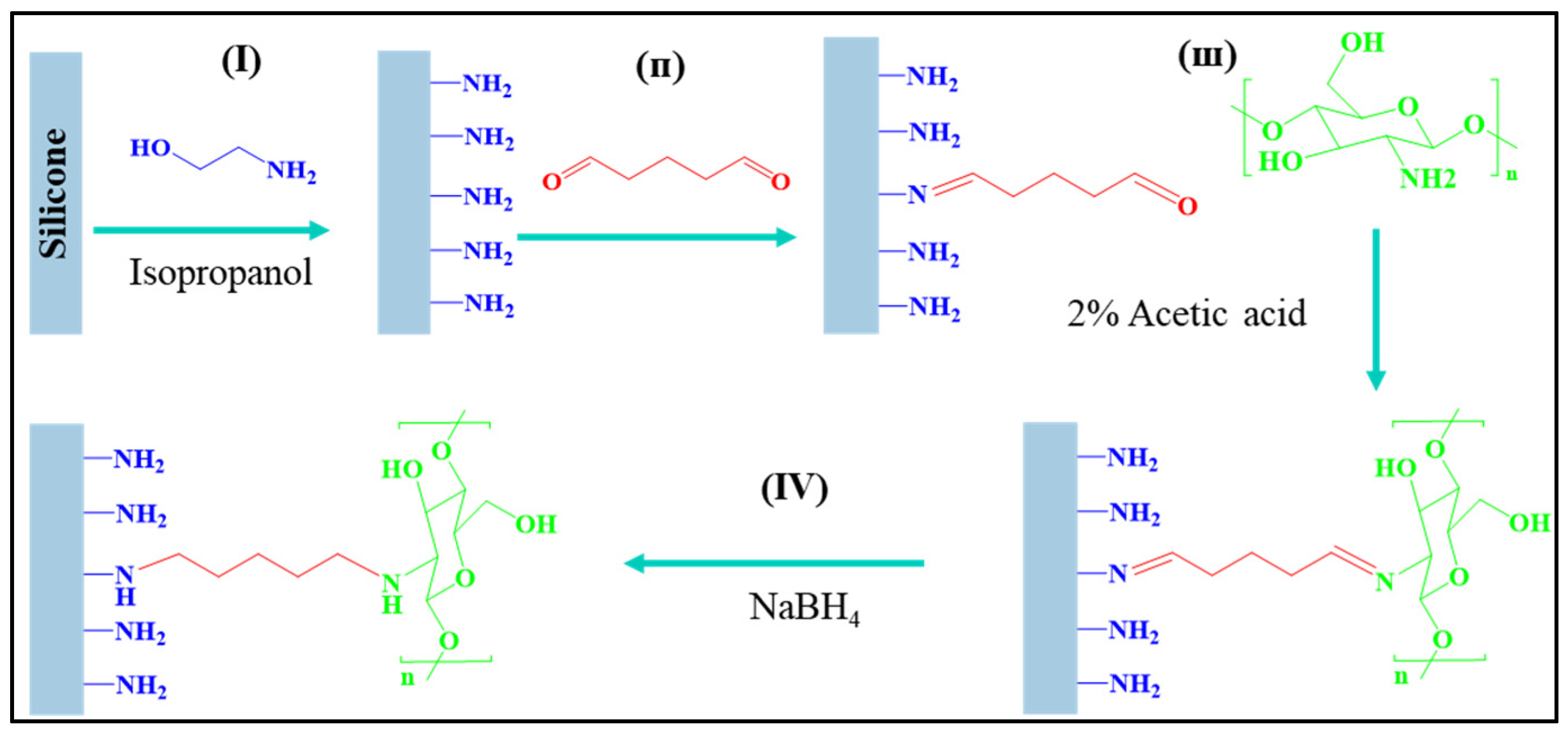

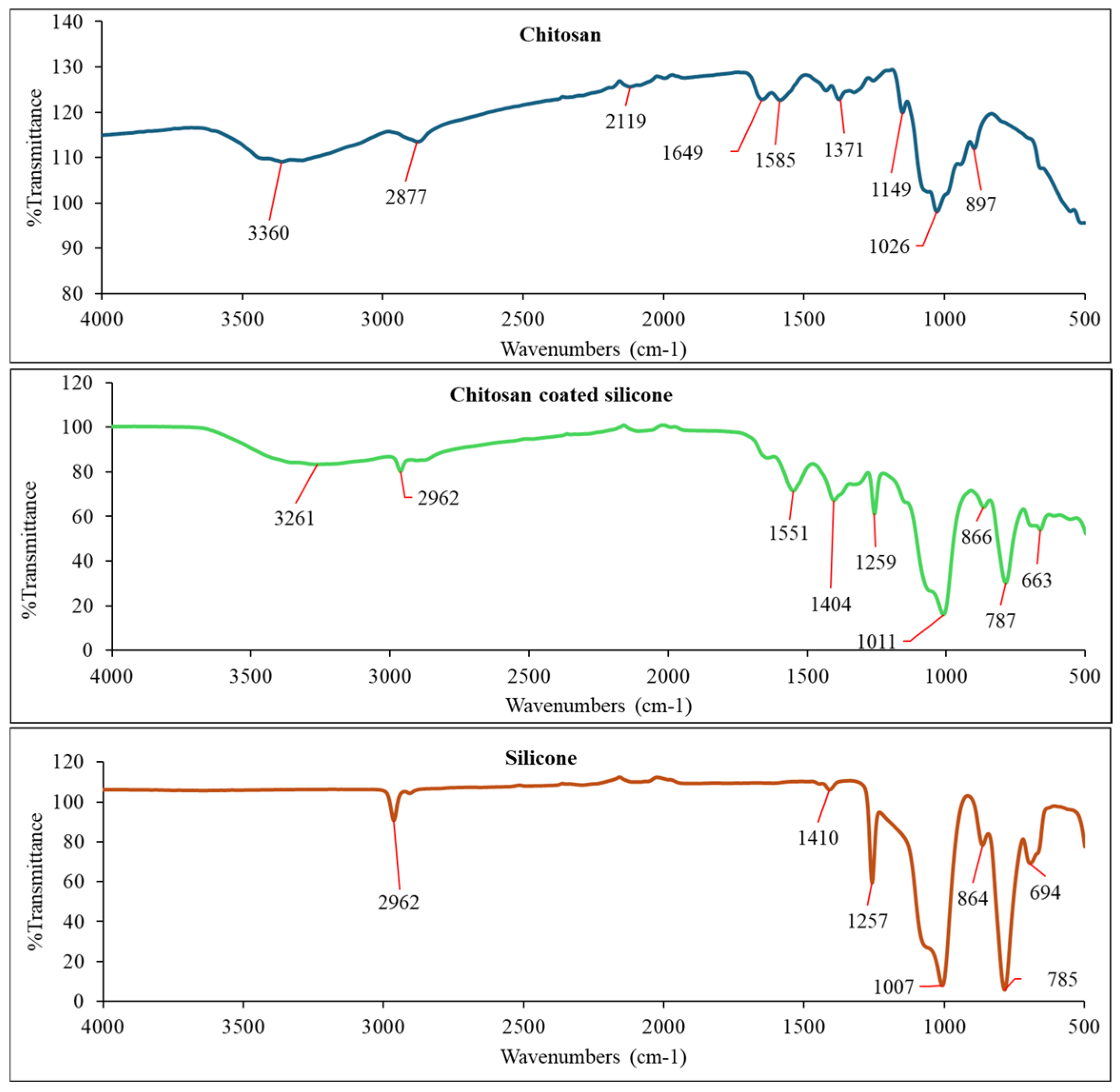

2.4. Chitosan Coating of ETA-Activated Silicone via Glutaraldehyde Crosslinking

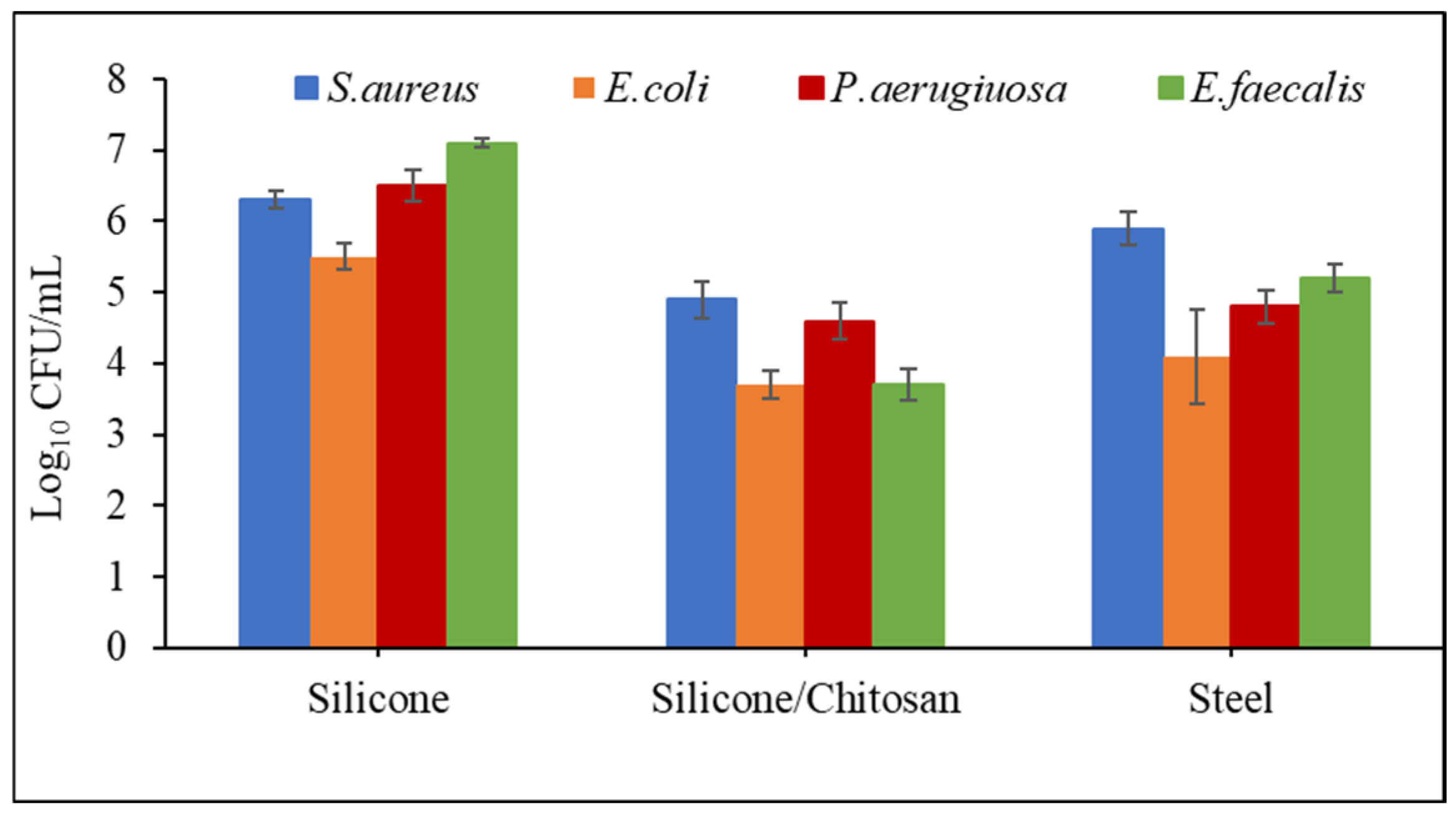

2.5. Antibacterial Properties

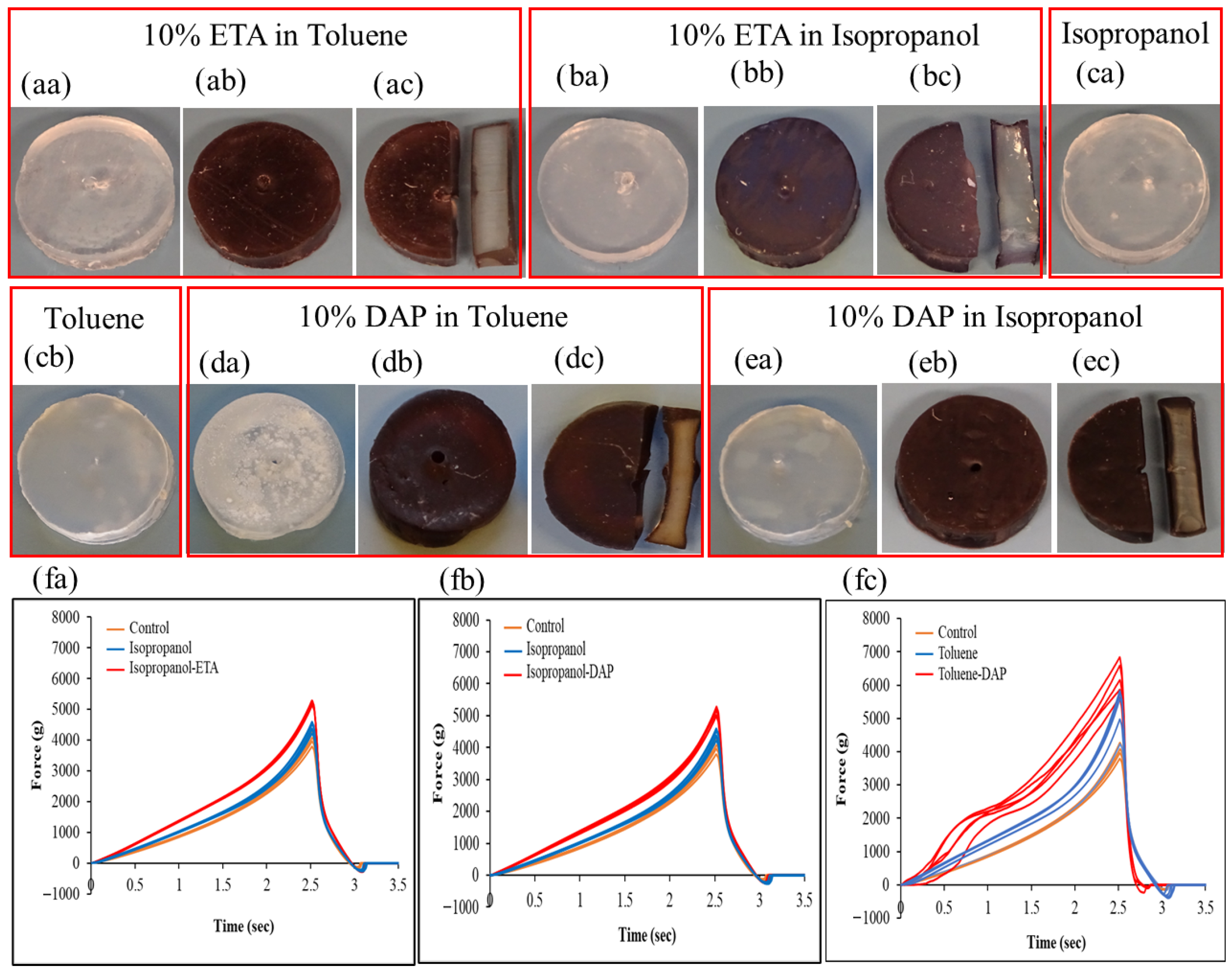

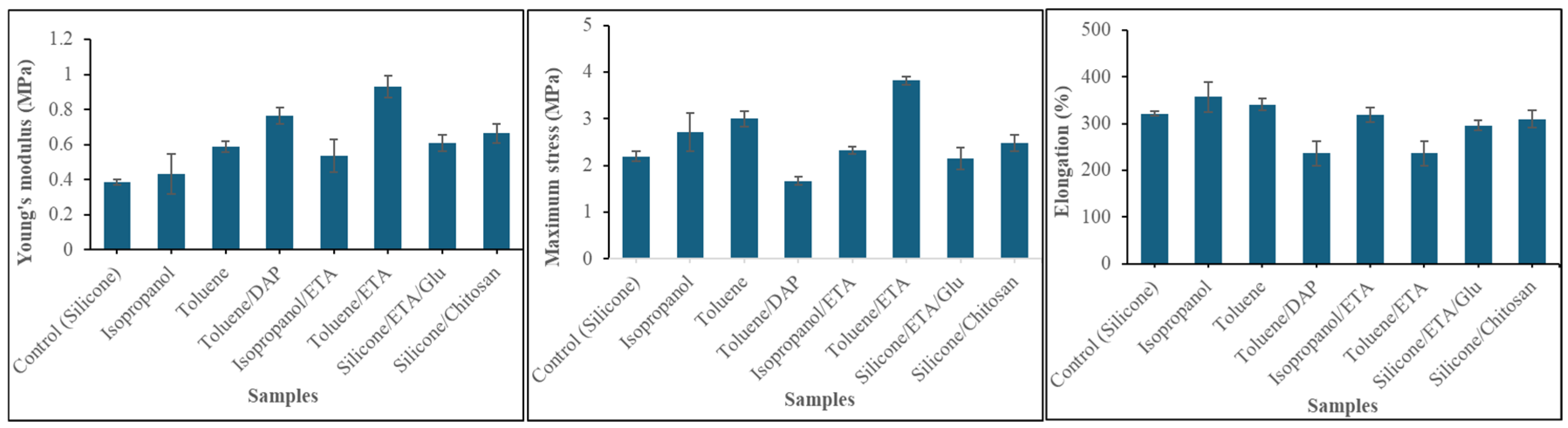

2.6. Impact of Amine Agents and Reaction Medium on the Tensile Properties of Silicone

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Methods and Preparations

3.2.1. Curing of Silicone Membranes and Sample Disc Preparation

3.2.2. Surface Characterization

3.2.3. Mechanical Testing

3.2.4. Ninhydrin Assay

3.2.5. Glutaraldehyde Treatment

3.2.6. Investigation of the Effects of ETA Concentration on Silicone Surface Activation in Various Reaction Media

3.2.7. Fluorescence Labeling

3.2.8. Stability Study

3.2.9. Chitosan Coating

3.2.10. Antibacterial Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| APD | 3-Amino-1,2-propanediol |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| DAP | 1,3-Diaminopropane |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DMF | N,N-dimethylformamide |

| DA% | Degree of acetylation |

| EDA | Ethylenediamine |

| ETA | Ethanolamine |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| Glu | Glutaraldehyde |

| MHA | Mueller-Hinton agar |

| MH | Mueller-Hinton broth |

| NaBH4 | Sodium borohydride |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| P(DMAPS) | Poly((2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl)dimethyl-(3-sulfopropyl)ammonium hydroxide) |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscope |

References

- Lawrence, E.L.; Turner, I.G. Materials for Urinary Catheters: A Review of Their History and Development in the UK. Med. Eng. Phys. 2005, 27, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Luo, G.; Xia, H.; He, W.; Zhao, J.; Liu, B.; Tan, J.; Zhou, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Novel Bilayer Wound Dressing Composed of Silicone Rubber with Particular Micropores Enhanced Wound Re-Epithelialization and Contraction. Biomaterials 2015, 40, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spear, S.L.; Murphy, D.K.; Allergan Silicone Breast Implant U.S. Core Clinical Study Group. Natrelle Round Silicone Breast Implants: Core Study Results at 10 Years. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 133, 1354–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coroneos, C.J.; Selber, J.C.; Offodile, A.C.; Butler, C.E.; Clemens, M.W. US FDA Breast Implant Postapproval Studies: Long-Term Outcomes in 99,993 Patients. Ann. Surg. 2019, 269, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Ghomi, E.R.; Venkatraman, P.D.; Ramakrishna, S. Silicone-Based Biomaterials for Biomedical Applications: Antimicrobial Strategies and 3D Printing Technologies. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacka, J.; Donoghue, J.; Sutherland, M.; Martincich, I.; Mitten-Lewis, S.; Morris, P.; Meredith, G. Dwell Time and Functional Failure in Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Tubes: A Prospective Randomized-Controlled Comparison between Silicon Polymer and Polyurethane Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Tubes. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 20, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, J.T.; Burgess, B.J.; Galler, D.; Nadol, J.B., Jr. Foreign Body Response to Silicone in Cochlear Implant Electrodes in the Human. Otol. Neurotol. 2017, 38, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liravi, F.; Toyserkani, E. Additive Manufacturing of Silicone Structures: A Review and Prospective. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 24, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmo, A.C.; Grunlan, M.A. Biomedical Silicones: Leveraging Additive Strategies to Propel Modern Utility. ACS Macro Lett. 2023, 12, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayani, B.; Dilhari, A.; Kottegoda, N.; Ratnaweera, D.R.; Weerasekera, M.M. Reduced Crystalline Biofilm Formation on Superhydrophobic Silicone Urinary Catheter Materials. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 11488–11496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeribi, R.; Bouchloukh, W.; Jouenne, T.; Menaa, B. Characterization of Bacterial Biofilms Formed on Urinary Catheters. Am. J. Infect. Control 2012, 40, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radd, I.; Costerton, W.; Sabharwal, U.; Sacilowski, M.; Anaissie, E.; Bodey, G.P. Ultrastructural Analysis of Indwelling Vascular Catheters: A Quantitative Relationship between Luminal Colonization and Duration of Placement. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 168, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.; Migonney, V.; Falentin-Daudre, C. Review of Silicone Surface Modification Techniques and Coatings for Antibacterial/Antimicrobial Applications to Improve Breast Implant Surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2021, 121, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolle, L.E. Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infections. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2014, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubi, H.; Mudey, G.; Kunjalwar, R. Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI). Cureus 2022, 14, e30385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Yuan, X. Antimicrobial Strategies for Urinary Catheters. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Seenivasan, M.K.; Inbarajan, A. A Literature Review on Biofilm Formation on Silicone and Poymethyl Methacrylate Used for Maxillofacial Prostheses. Cureus 2021, 13, e20029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkanci, A.; Tunçcan, Ö.G. Biofilm-Related Infection: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Mediterr. J. Infect. Microbes Antimicrob. 2019, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatoon, Z.; McTiernan, C.D.; Suuronen, E.J.; Mah, T.-F.; Alarcon, E.I. Bacterial Biofilm Formation on Implantable Devices and Approaches to Its Treatment and Prevention. Heliyon 2018, 4, e01067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetrick, E.M.; Schoenfisch, M.H. Reducing Implant-Related Infections: Active Release Strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Azghani, A.O.; Omri, A. Antimicrobial Efficacy of a New Antibiotic-Loaded Poly(Hydroxybutyric-Co-Hydroxyvaleric Acid) Controlled Release System. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2004, 54, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Pareek, V.; Roy Choudhury, S.; Panwar, J.; Karmakar, S. Superior Bactericidal Efficacy of Fucose-Functionalized Silver Nanoparticles against Pseudomonas Aeruginosa PAO1 and Prevention of Its Colonization on Urinary Catheters. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 29325–29337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Q.; Chang, H.-E.; Francis, R.; Olszowy, H.; Liu, P.-Y.; Kempf, M.; Cuttle, L.; Kravchuk, O.; Phillips, G.E.; Kimble, R.M. Silver Deposits in Cutaneous Burn Scar Tissue Is a Common Phenomenon Following Application of a Silver Dressing. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2009, 36, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knetsch, M.L.W.; Koole, L.H. New Strategies in the Development of Antimicrobial Coatings: The Example of Increasing Usage of Silver and Silver Nanoparticles. Polymers 2011, 3, 340–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinese, C.; Jebors, S.; Echalier, C.; Licznar-Fajardo, P.; Garric, X.; Humblot, V.; Calers, C.; Martinez, J.; Mehdi, A.; Subra, G. Simple and Specific Grafting of Antibacterial Peptides on Silicone Catheters. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 3067–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Neoh, K.G.; Xu, L.Q.; Wang, R.; Kang, E.-T.; Lau, T.; Olszyna, D.P.; Chiong, E. Surface Modification of Silicone for Biomedical Applications Requiring Long-Term Antibacterial, Antifouling, and Hemocompatible Properties. Langmuir 2012, 28, 16408–16422, Correction in Langmuir 2012, 28, 17859. https://doi.org/10.1021/la3047017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zha, W.; Li, X. Tough Hydrogel Coating on Silicone Rubber with Improved Antifouling and Antibacterial Properties. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 3462–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Másson, M. Antimicrobial Properties of Chitosan and Its Derivatives. In Chitosan for Biomaterials III: Structure-Property Relationships; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 131–168. [Google Scholar]

- Másson, M. Chitin and Chitosan. In Handbook of Hydrocolloids; Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 1039–1072. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar, R.; Prabaharan, M.; Kumar, P.T.S.; Nair, S.V.; Tamura, H. Biomaterials Based on Chitin and Chitosan in Wound Dressing Applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, B.H.; Kim, B.H.; Kim, S.; Lee, K.; Choy, Y.B.; Heo, C.Y. Silicone Breast Implant Modification Review: Overcoming Capsular Contracture. Biomater. Res. 2018, 22, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata, A.; Fleischman, A.J.; Roy, S. Characterization of Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Properties for Biomedical Micro/Nanosystems. Biomed. Microdevices 2005, 7, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efimenko, K.; Crowe, J.A.; Manias, E.; Schwark, D.W.; Fischer, D.A.; Genzer, J. Rapid Formation of Soft Hydrophilic Silicone Elastomer Surfaces. Polymer 2005, 46, 9329–9341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.K.; Chen, J.Y.; Wang, L.P.; Huang, N. Plasma-Surface Modification of Biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2002, 36, 143–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, E.C.; Gadioli, G.Z.; Cruz, N.C. Investigations on the Stability of Plasma Modified Silicone Surfaces. Plasmas Polym. 2004, 9, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cui, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G. Effects of Different Silanization Followed via the Sol-Gel Growing of Silica Nanoparticles onto Carbon Fiber on Interfacial Strength of Silicone Resin Composites. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2018, 707, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.-B.; Chen, C.-S.; Chen, W.-Y.; Huang, C.-J. Modification of Silicone Elastomer with Zwitterionic Silane for Durable Antifouling Properties. Langmuir 2014, 30, 11386–11393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.C.; Jerrett, M.; Pope, C.A., III; Krewski, D.; Gapstur, S.M.; Diver, W.R.; Beckerman, B.S.; Marshall, J.D.; Su, J.; Crouse, D.L.; et al. Long-Term Ozone Exposure and Mortality in a Large Prospective Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, M.A. Organosilanes: Where to Find Them, What to Call Them, How to Detect Them; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Ikeda, Y.; Oku, A. Recovery of Monomers and Fillers from High-Temperature-Vulcanized Silicone Rubbers—Combined Effects of Solvent, Base and Fillers. Polymer 2002, 43, 7295–7300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Huang, W.; Oku, A. Recycling of Monomers and Fillers from High-Temperature-Vulcanized Silicone Rubber Using Tetramethylammonium Hydroxide. Green Chem. 2003, 5, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oku, A.; Huang, W.; Ikeda, Y. Monomer Recycling for Vulcanized Silicone Rubbers in the Form of Cyclosiloxane Monomers. Role of Acid Buffers. Polymer 2002, 43, 7289–7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmel, K.-H.; Schulz, J. Polysiloxane. 4. Zum Verhalten Linearer Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) in Diethylamin. Acta Polym. 1987, 38, 536–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achternbosch, M.; Zibula, L.; Kirchhoff, J.-L.; Bauer, J.O.; Strohmann, C. Primary Amine Functionalization of Alkoxysilanes: Synthesis, Selectivity, and Mechanistic Insights. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 11562–11568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabczyk, A.; Kudłacik-Kramarczyk, S.; Głab, M.; Kedzierska, M.; Jaromin, A.; Mierzwiński, D.; Tyliszczak, B. Physicochemical Investigations of Chitosan-Based Hydrogels Containing Aloe Vera Designed for Biomedical Use. Materials 2020, 13, 3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Qiu, W.; Liu, B.; Guo, Q. Stable Superhydrophobic Surface Based on Silicone Combustion Product. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 56259–56262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grass, G.; Rensing, C.; Solioz, M. Metallic Copper as an Antimicrobial Surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1541–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 846:2019; Plastics. Evaluation of the Activity of Microorganisms. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Leane, M.M.; Nankervis, R.; Smith, A.; Illum, L. Use of the Ninhydrin Assay to Measure the Release of Chitosan from Oral Solid Dosage Forms. Int. J. Pharm. 2004, 271, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reaction Media | Amine-Based Agents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APD * | DAP * | ETA * | EDA * | |

| Isopropanol | 44 ± 1 | 105 ± 3 | 303 ± 31 | 87 ± 4 |

| Water | 30 ± 5 | 36 ± 2 | 62 ± 2 | 40 ± 2 |

| Toluene | 111 ± 3 | 345 ± 2 | 644 ± 30 | 156 ± 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amani, D.; Baldvinsdóttir, G.E.; Nagy, V.; Thorsteinsson, F.; Másson, M. Eco-Friendly Activation of Silicone Surfaces and Antimicrobial Coating with Chitosan Biopolymer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412084

Amani D, Baldvinsdóttir GE, Nagy V, Thorsteinsson F, Másson M. Eco-Friendly Activation of Silicone Surfaces and Antimicrobial Coating with Chitosan Biopolymer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412084

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmani, Daniel, Guðný E. Baldvinsdóttir, Vivien Nagy, Freygardur Thorsteinsson, and Már Másson. 2025. "Eco-Friendly Activation of Silicone Surfaces and Antimicrobial Coating with Chitosan Biopolymer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412084

APA StyleAmani, D., Baldvinsdóttir, G. E., Nagy, V., Thorsteinsson, F., & Másson, M. (2025). Eco-Friendly Activation of Silicone Surfaces and Antimicrobial Coating with Chitosan Biopolymer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12084. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412084