Ensuring the Safe Use of Bee Products: A Review of Allergic Risks and Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

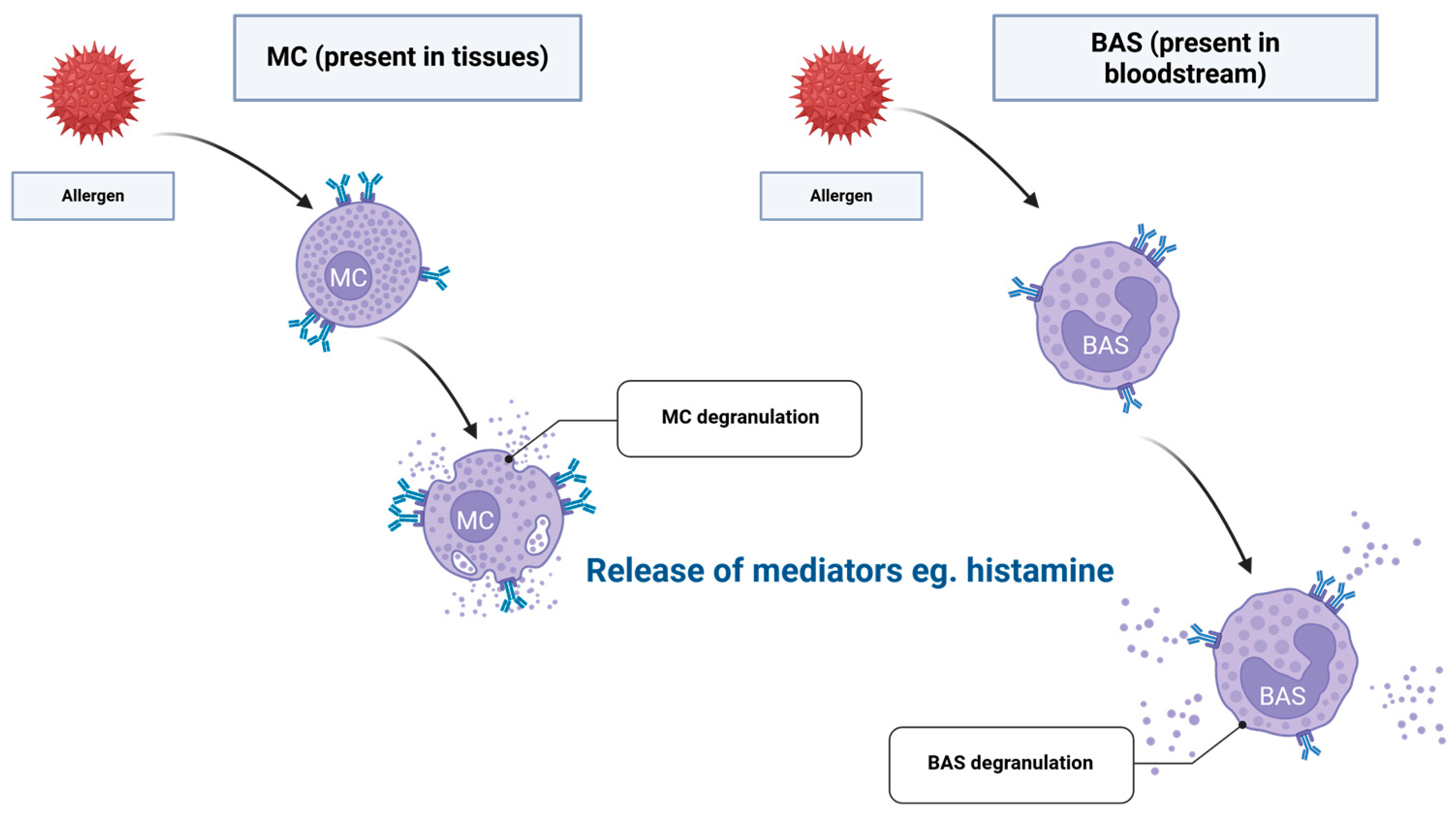

2. Immunological Mechanisms of Sensitisation to HBPs

3. Allergenic Profiles of the Selected HBPs

3.1. Honey

3.2. Bee Pollen

3.3. Bee Bread

3.4. Royal Jelly

3.5. Propolis

3.6. Beeswax

3.7. Bee Brood

3.8. Toxicological Assessment of HBPs via In Vitro Models

4. Diagnosis and Management of HBP Allergy

4.1. Diagnostic Approaches to HBP Allergy

4.2. Pharmacological Management of HBP Allergy

4.3. Future Directions in Research and Clinical Management

5. At-Risk Populations and Confounding Factors

6. Gaps in Knowledge and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 10-HDA | 10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid |

| APC | Antigen-presenting cells |

| BAS | Basophils |

| BAT | Basophil activation test |

| BB | Bee bread |

| BP | Bee pollen |

| BPH | Birch pollen honey |

| BW | Beeswax |

| CCDs | Cross-reactive carbohydrate determinants |

| CD40L | Cluster of Differentiation 40 Ligand |

| CRD | Component-resolved diagnostics |

| DC | Dendritic cells |

| FMI | Fragrance mix I |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| HBPs | Honeybee products |

| HBV | Honeybee venom |

| HDM | House dust mite |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| IL | Interleukin |

| ILC2 | Innate lymphoid type 2 cells |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| Mφ | Macrophages |

| MC | Mast cells |

| MetE | Cobalamin-independent methionine synthase |

| MHC II | Major histocompatibility complex class II |

| MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| MRJP | Major royal jelly protein |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide test |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NK-T | Natural Killer T cells |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OIT | Oral immunotherapy |

| PAF | Platelet-activating factor |

| PFAS | Pollen-Food Allergy Syndrome |

| RAST | Radioallergosorbent test |

| RJ | Royal jelly |

| RH | Regular honey |

| sIgE | Specific Immunoglobulin E |

| SPT | Skin-prick test |

| SRB | Sulforhodamine B |

| Tfh | T follicular helper |

| Th | Naïve T-helper cells |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor alpha |

| TNF-β | Tumour necrosis factor beta |

| Treg | Regulatory T cells |

| TSLP | Thymic stromal lymphopoietin |

References

- Kowalczuk, I.; Gębski, J.; Stangierska, D.; Szymańska, A. Determinants of Honey and Other Bee Products Use for Culinary, Cosmetic, and Medical Purposes. Nutrients 2023, 15, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merdan, K. Analysis of Bee Products in Terms of Global Production, Consumption, and International Trade. In Research & Reviews in Agriculture, Forestry and Aquaculture Sciences-II; Gece Publishing: Ankara, Turkey, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 113–126. ISBN 978-625-8002-50-8. [Google Scholar]

- Weis, W.A.; Ripari, N.; Conte, F.L.; Honorio, M.d.S.; Sartori, A.A.; Matucci, R.H.; Sforcin, J.M. An Overview about Apitherapy and Its Clinical Applications. Phytomed. Plus 2022, 2, 100239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornara, L.; Biagi, M.; Xiao, J.; Burlando, B. Therapeutic Properties of Bioactive Compounds from Different Honeybee Products. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliai, G.; Dinu, M.; Madarena, M.P.; Bonaccio, M.; Iacoviello, L.; Sofi, F. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 125, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnuqaydan, A.M. The Dark Side of Beauty: An in-Depth Analysis of the Health Hazards and Toxicological Impact of Synthetic Cosmetics and Personal Care Products. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1439027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunne, F.J. The ‘Natural Health Service’: Natural Does Not Mean Safe. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2009, 15, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes, L. Allergy to Honeybee … Not Only Stings. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 15, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucu, A.-A.; Baci, G.-M.; Moise, A.R.; Dezsi, Ş.; Marc, B.D.; Stângaciu, Ş.; Dezmirean, D.S. Towards a Better Understanding of Nutritional and Therapeutic Effects of Honey and Their Applications in Apitherapy. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma, S.T.; Bobiş, O.; Bonta, V.; Acaroz, U.; Shah, S.R.A.; Istanbullugil, F.R.; Arslan-Acaroz, D. General Nutritional Profile of Bee Products and Their Potential Antiviral Properties against Mammalian Viruses. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bava, R.; Castagna, F.; Lupia, C.; Poerio, G.; Liguori, G.; Lombardi, R.; Naturale, M.D.; Bulotta, R.M.; Biondi, V.; Passantino, A.; et al. Hive Products: Composition, Pharmacological Properties, and Therapeutic Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenta, R.; Hochwallner, H.; Linhart, B.; Pahr, S. Food Allergies: The Basics. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 1120–1131.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.H. Pollen-Food Allergy Syndrome in Children. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2020, 63, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.; Nielsen, M.; Sette, A. T Cell Epitope Predictions. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidney, J.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. Epitope Prediction and Identification- Adaptive T Cell Responses in Humans. Semin. Immunol. 2020, 50, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jutel, M.; Agache, I.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M.; Akdis, M.; Chivato, T.; del Giacco, S.; Gajdanowicz, P.; Gracia, I.E.; Klimek, L.; Lauerma, A.; et al. Nomenclature of Allergic Diseases and Hypersensitivity Reactions: Adapted to Modern Needs: An EAACI Position Paper. Allergy 2023, 78, 2851–2874, Correction in Allergy 2024, 79, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzaman, A.; Cho, S.H. Chapter 28: Classification of Hypersensitivity Reactions. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2012, 33, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platts-Mills, T.A.E. The Role of Immunoglobulin E in Allergy and Asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, B.T.; Grayson, M.H. Immunoglobulin E, What Is It Good For? Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016, 116, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, O.T.; Oettgen, H.C. Beyond Immediate Hypersensitivity: Evolving Roles for IgE Antibodies in Immune Homeostasis and Allergic Diseases. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 242, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamji, M.H.; Valenta, R.; Jardetzky, T.; Verhasselt, V.; Durham, S.R.; Würtzen, P.A.; van Neerven, R.J.J. The Role of Allergen-specific IgE, IgG and IgA in Allergic Disease. Allergy 2021, 76, 3627–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, K.D.; Prussin, C.; Metcalfe, D.D. IgE, Mast Cells, Basophils, and Eosinophils. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, S73–S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitte, J.; Vibhushan, S.; Bratti, M.; Montero-Hernandez, J.E.; Blank, U. Allergy, Anaphylaxis, and Nonallergic Hypersensitivity: IgE, Mast Cells, and Beyond. Med. Princ. Pract. 2022, 31, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Goldin, J. Type I Hypersensitivity Reaction. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, M.-T.; Chang, W.-C.; Pao, S.-C.; Hung, S.-I. Delayed Drug Hypersensitivity Reactions: Molecular Recognition, Genetic Susceptibility, and Immune Mediators. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibril, F.I.; Hilmi, A.B.M.; Manivannan, L. Isolation and Characterization of Polyphenols in Natural Honey for the Treatment of Human Diseases. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Shi, F.; He, X.; Cai, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yao, D.; Zhou, J.; Wei, X. Establishment and Application of Quantitative Method for 22 Organic Acids in Honey Based on SPE-GC–MS. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarghandian, S.; Farkhondeh, T.; Samini, F. Honey and Health: A Review of Recent Clinical Research. Pharmacogn. Res. 2017, 9, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Bai, W.; Xiao, G.; Liu, G. Composition, Functional Properties and Safety of Honey: A Review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 6767–6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, S.; Jurendic, T.; Sieber, R.; Gallmann, P. Honey for Nutrition and Health: A Review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2008, 27, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Costanzo, M.; De Paulis, N.; Peveri, S.; Montagni, M.; Berni Canani, R.; Biasucci, G. Anaphylaxis Caused by Artisanal Honey in a Child: A Case Report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2021, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steininger, J.; Heyne, S.; Abraham, S.; Beissert, S.; Bauer, A. Honey as a Rare Cause of Severe Anaphylaxis: Case Report and Review of Literature. JEADV Clin. Pract. 2025, 4, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, R.; Duarte, F.C.; Mendes, A.; Bartolomé, B.; Barbosa, M.P. Anaphylaxis Caused by Honey: A Case Report. Asia Pac. Allergy 2017, 7, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ključevšek, T.; Kreft, S. Allergic Potential of Medicinal Plants From the Asteraceae Family. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Végh, R.; Csóka, M.; Sörös, C.; Sipos, L. Underexplored Food Safety Hazards of Beekeeping Products: Key Knowledge Gaps and Suggestions for Future Research. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altameemi, H.; Sarheed, N.M.; Zaker, K.A.; Zaidan, S. Honey Allergy, First Documentation in Iraq—A Case Report. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw Yong, P.Y.; Islam, F.; Harith, H.H.; Israf, D.A.; Tan, J.W.; Tham, C.L. The Potential Use of Honey as a Remedy for Allergic Diseases: A Mini Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 599080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, K.; Jantunen, J.; Haahtela, T. Birch Pollen Honey for Birch Pollen Allergy—A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2010, 155, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, L.; Kohlich, A.; Hirschwehr, R.; Siemanna, U.; Ebner, H.; Scheiner, O.; Kraft, D.; Ebner, C. Food Allergy to Honey: Pollen or Bee Products?: Characterization of Allergenic Proteins in Honey by Means of Immunoblotting. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1996, 97, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burzyńska, M.; Piasecka-Kwiatkowska, D.; Springer, E. Allergenic Properties of Polish Nectar Honeys. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2020, 19, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbling, A.; Peter, C.H.; Berchtold, E.; Bogdanov, S.; Müller, U. Allergy to Honey: Relation to Pollen and Honey Bee Allergy. Allergy 1992, 47, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, S.; Haneefa, S.M.; Fernandez-Cabezudo, M.J.; Giampieri, F.; al-Ramadi, B.K.; Battino, M. Therapeutic and Preventive Properties of Honey and Its Bioactive Compounds in Cancer: An Evidence-Based Review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2020, 33, 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, W.Y.; Gabry, M.S.; El-Shaikh, K.A.; Othman, G.A. The Anti-Tumor Effect of Bee Honey in Ehrlich Ascite Tumor Model of Mice Is Coincided with Stimulation of the Immune Cells. Egypt. J. Immunol. 2008, 15, 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Majtan, J.; Bohova, J.; Garcia-Villalba, R.; Tomas-Barberan, F.A.; Madakova, Z.; Majtan, T.; Majtan, V.; Klaudiny, J. Fir Honeydew Honey Flavonoids Inhibit TNF-α-Induced MMP-9 Expression in Human Keratinocytes: A New Action of Honey in Wound Healing. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2013, 305, 619–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoone, P.; Warnock, M.; Fyfe, L. Honey: An Immunomodulatory Agent for Disorders of the Skin. Food Agric. Immunol. 2016, 27, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majtan, J.; Kumar, P.; Majtan, T.; Walls, A.F.; Klaudiny, J. Effect of Honey and Its Major Royal Jelly Protein 1 on Cytokine and MMP-9 mRNA Transcripts in Human Keratinocytes. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, e73–e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzyńska, M.; Piasecka-Kwiatkowska, D. A Review of Honeybee Venom Allergens and Allergenicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, M.; Nanda, V. Composition and Functionality of Bee Pollen: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 98, 82–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.G.R.; Frigerio, C.; Lopes, J.; Bogdanov, S. What Is the Future of Bee-Pollen? J. ApiProd. ApiMed. Sci. 2010, 2, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komosinska-Vassev, K.; Olczyk, P.; Kaźmierczak, J.; Mencner, L.; Olczyk, K. Bee Pollen: Chemical Composition and Therapeutic Application. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 297425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, K.C.P.; Figueiredo, C.A.V.; Figueredo, T.B.; Freire, K.R.L.; Santos, F.A.R.; Alcantara-Neves, N.M.; Silva, T.M.S.; Piuvezam, M.R. Anti-Allergic Effect of Bee Pollen Phenolic Extract and Myricetin in Ovalbumin-Sensitized Mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 119, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-H.; Jang, Y.-S.; Oh, J.-W.; Kim, C.-H.; Hyun, I.-G. Bee Pollen-Induced Anaphylaxis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2015, 7, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagdis, A.; Sussman, G. Anaphylaxis from Bee Pollen Supplement. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2012, 184, 1167–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberger, P.A.; Flais, M.J. Bee Pollen-Induced Anaphylactic Reaction in an Unknowingly Sensitized Subject. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001, 86, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, K.B.; Pien, L. Exercise-Induced Anaphylaxis Associated with the Use of Bee Pollen. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 122, 118–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leang, Z.X.; Thalayasingam, M.; O’Sullivan, M. A Paediatric Case of Exercise-Augmented Anaphylaxis Following Bee Pollen Ingestion in Western Australia. Asia Pac. Allergy 2022, 12, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.H.; Yunginger, J.W.; Rosenberg, N.; Fink, J.N. Acute Allergic Reaction after Composite Pollen Ingestion. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1979, 64, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Muñoz, M.F.; Bartolome, B.; Caminoa, M.; Bobolea, I.; Garcia Ara, M.C.; Quirce, S. Bee Pollen: A Dangerous Food for Allergic Children. Identification of Responsible Allergens. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2010, 38, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitsios, C.; Chliva, C.; Mikos, N.; Kompoti, E.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Kontou-Fili, K. Bee Pollen Sensitivity in Airborne Pollen Allergic Individuals. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006, 97, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonotte-Varly, C. In Vivo Biological Potency of Fraxinus Bee-Collected Pollen on Patients Allergic to Oleaceae. Alergol. Pol.-Pol. J. Allergol. 2015, 2, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Tokura, T.; Nakano, N.; Hara, M.; Niyonsaba, F.; Ushio, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Tadokoro, T.; Okumura, K.; Ogawa, H. Inhibitory Effect of Honeybee-Collected Pollen on Mast Cell Degranulation In Vivo and In Vitro. J. Med. Food 2008, 11, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, Y.; Tokura, T.; Ushio, H.; Niyonsaba, F.; Yamamoto, Y.; Tadokoro, T.; Ogawa, H.; Okumura, K. Lipid-Soluble Components of Honeybee-Collected Pollen Exert Antiallergic Effect by Inhibiting IgE-Mediated Mast Cell Activation in Vivo. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 1581–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilles-Stein, S.; Beck, I.; Chaker, A.; Bas, M.; McIntyre, M.; Cifuentes, L.; Petersen, A.; Gutermuth, J.; Schmidt-Weber, C.; Behrendt, H.; et al. Pollen Derived Low Molecular Compounds Enhance the Human Allergen Specific Immune Response in Vivo. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2016, 46, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, M.; Kino, K.; Takishita, T.; Hattori, H.; Ogawa, T.; Yoshino, T.; Yokoyama, M.; Nishizaki, K. Roles of Carbohydrates on Cry j 1, the Major Allergen of Japanese Cedar Pollen, in Specific T-Cell Responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001, 108, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batanero, E.; Crespo, J.F.; Monsalve, R.I.; Martín-Esteban, M.; Villalba, M.; Rodríguez, R. IgE-Binding and Histamine-Release Capabilities of the Main Carbohydrate Component Isolated from the Major Allergen of Olive Tree Pollen, Ole e 1. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 103, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, T.; Choi, Y.-S.; Nam, B.-Y.; Uh, S.T.; Park, J.S.; Kim, Y.-H.; Paik, Y.-K.; Park, C.-S. Plasma Protein Profiles in Early Asthmatic Responses to Inhalation Allergen Challenge. Allergy 2009, 64, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska, E.; Plewa, S.; Pietkiewicz, D.; Kossakowski, K.; Matysiak, J.; Rosiński, G.; Matysiak, J. Mass Spectrometry-Based Identification of Bioactive Bee Pollen Proteins: Evaluation of Allergy Risk after Bee Pollen Supplementation. Molecules 2022, 27, 7733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Yin, S.; Fu, L.; Wang, M.; Meng, L.; Li, F.; Xue, X.; Wu, L.; Li, Q. Identification of Allergens and Allergen Hydrolysates by Proteomics and Metabolomics: A Comparative Study of Natural and Enzymolytic Bee Pollen. Food Res. Int. 2022, 158, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.P.; Verma, J.; Rai, D.; Sridhara, S.; Gaur, S.N.; Gangal, S.V. Immunobiochemical Characterization of Brassica Campestris Pollen Allergen. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1995, 108, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denisow-Pietrzyk, M.; Pietrzyk, Ł.; Denisow, B. Asteraceae Species as Potential Environmental Factors of Allergy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 6290–6300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Sun, J.-L.; Yin, J.; Li, Z. Artemisia Allergy Research in China. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 179426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bains, S.; Lang, D.M.; Han, Y.; Hsieh, F.H. Characterizing the Allergens Contained in Goldenrod (Solidago virgaurea). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008, 121, S175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, J.; Dhivert, H.; Clauzel, A.-M.; Hewitt, B.; Michel, F.-B. Occupational Allergy to Sunflower Pollen. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1985, 75, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Hoz, F.; Melero, J.A.; González, R.; Carreira, J. Isolation and Partial Characterization of Allergens from Helianthus Annuus (Sunflower) Pollen. Allergy 1994, 49, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.W.; Choi, S.Y.; Lee, E.K.; Sohn, J.H.; Park, J.-W.; Hong, C.-S. Cross-Allergenicity of Pollens from the Compositae Family: Artemisia vulgaris, Dendranthema grandiflorum, and Taraxacum officinale. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007, 99, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mur, P.; Feo Brito, F.; Lombardero, M.; Barber, D.; Galindo, P.A.; Gómez, E.; Borja, J. Allergy to Linden Pollen (Tilia Cordata). Allergy 2001, 56, 457–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărgăoan, R.; Stranț, M.; Varadi, A.; Topal, E.; Yücel, B.; Cornea-Cipcigan, M.; Campos, M.G.; Vodnar, D.C. Bee Collected Pollen and Bee Bread: Bioactive Constituents and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakour, M.; Laaroussi, H.; Ousaaid, D.; El Ghouizi, A.; Es-Safi, I.; Mechchate, H.; Lyoussi, B. Bee Bread as a Promising Source of Bioactive Molecules and Functional Properties: An Up-To-Date Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urcan, A.C. Health Benefits and Uses of Bee Bread in Medicine. In Bee Products–Chemical and Biological Properties; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 473–491. ISBN 978-3-031-89049-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kosedag, M.; Gulaboglu, M. Pollen and Bee Bread Expressed Highest Anti-Inflammatory Activities among Bee Products in Chronic Inflammation: An Experimental Study with Cotton Pellet Granuloma in Rats. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 1967–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samtiya, M.; Aluko, R.E.; Puniya, A.K.; Dhewa, T. Enhancing Micronutrients Bioavailability through Fermentation of Plant-Based Foods: A Concise Review. Fermentation 2021, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, J.A.; Njobeh, P.B.; Gbashi, S.; Oyedeji, A.B.; Ogundele, O.M.; Oyeyinka, S.A.; Adebo, O.A. Fermentation of Cereals and Legumes: Impact on Nutritional Constituents and Nutrient Bioavailability. Fermentation 2022, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw Terefe, N.; Augustin, M.A. Fermentation for Tailoring the Technological and Health Related Functionality of Food Products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2887–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenbaum, M.R.; Johnson, R.M. Xenobiotic Detoxification Pathways in Honey Bees. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 10, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Cui, Q.; Wan, Y.; Fu, G.; Chen, H.; Cheng, J. Recent Advances in Alleviating Food Allergenicity through Fermentation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 7255–7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghaish, S.; Ahmadova, A.; Hadji-Sfaxi, I.; El Mecherfi, K.E.; Bazukyan, I.; Choiset, Y.; Rabesona, H.; Sitohy, M.; Popov, Y.G.; Kuliev, A.A.; et al. Potential Use of Lactic Acid Bacteria for Reduction of Allergenicity and for Longer Conservation of Fermented Foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areczuk, A.; Barbaś, P.; Flaczyk, E.; Flaczyk, D.; Habryka, C.; Hęś, M.; Juzwa, W.; Kiełtyka-Dadasiewicz, A.; Kmiecik, D.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; et al. Pyłek Pszczeli Produktem Pracy Pszczół. In Bioprodukty–Pozyskiwanie, Właściwości i Zastosowanie w Produkcji Żywności; Wydział Nauk o Żywności i Żywieniu, Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy w Poznaniu: Poznań, Poland, 2016; pp. 13–20. ISBN 78-83-7160-835-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan, A.N.K.G.; Nair, A.J.; Sugunan, V.S. A Review on Royal Jelly Proteins and Peptides. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 44, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Campos, M.G.; Fratini, F.; Altaye, S.Z.; Li, J. New Insights into the Biological and Pharmaceutical Properties of Royal Jelly. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, B.; Wilde, J. Mleczko pszczele jako produkt dietetyczny i leczniczy. Biul. Nauk. 2002, 18, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, H.; Ikeda, T.; Kajita, K.; Fujioka, K.; Mori, I.; Okada, H.; Uno, Y.; Ishizuka, T. Effect of Royal Jelly Ingestion for Six Months on Healthy Volunteers. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Saiga, A.; Sato, M.; Miyazawa, I.; Shibata, M.; Takahata, Y.; Morimatsu, F. Royal Jelly Supplementation Improves Lipoprotein Metabolism in Humans. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2007, 53, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, M.; Aoki, M.; Kawana, S. Case of Anaphylaxis Caused by Ingestion of Royal Jelly. J. Dermatol. 2008, 35, 222–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahama, H.; Shimazu, T. Food-Induced Anaphylaxis Caused by Ingestion of Royal Jelly. J. Dermatol. 2006, 33, 424–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, Y.; Shibuya, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Tsunoda, T.; Moriyama, T.; Seishima, M. Major Royal Jelly Protein 3 as a Possible Allergen in Royal Jelly-Induced Anaphylaxis. J. Dermatol. 2011, 38, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-D.; Cui, L.; Xu, Y.-Y.; Guan, K. A Case of Anaphylaxis Caused by Major Royal Jelly Protein 3 of Royal Jelly and Its Cross-Reactivity with Honeycomb. J. Asthma Allergy 2021, 14, 1555–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, R.; Thien, F.C.K.; Baldo, B.; Czarny, D. Royal Jelly–Induced Asthma and Anaphylaxis: Clinical Characteristics and Immunologic Correlations. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1995, 96, 1004–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thien, F.C.K.; Leung, R.; Baldo, B.A.; Weinbr, J.A.; Plomley, R.; Czarny, D. Asthma and Anaphylaxis Induced by Royal Jelly. Clin. Exp. Allergy 1996, 26, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Matsuo, I.; Ohkido, M. Contact Dermatitis Due to Honeybee Royal Jelly. Contact Dermat. 1983, 9, 452–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, R.; Lam, C.W.; Ho, A.; Chan, J.K.; Choy, D.; Lai, C.K. Allergic Sensitisation to Common Environmental Allergens in Adult Asthmatics in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med. J. 1997, 3, 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Hata, T.; Furusawa-Horie, T.; Arai, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Seishima, M.; Ichihara, K. Studies of Royal Jelly and Associated Cross-Reactive Allergens in Atopic Dermatitis Patients. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonei, Y.; Shibagaki, K.; Tsukada, N.; Nagasu, N.; Inagaki, Y.; Miyamoto, K.; Suzuki, O.; Kiryu, Y. CASE REPORT: Haemorrhagic Colitis Associated with Royal Jelly Intake. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 1997, 12, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.-S.; Guan, K. Occupational Asthma Caused by Inhalable Royal Jelly and Its Cross-Reactivity with Honeybee Venom. Chin. Med. J. 2016, 129, 2888–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testi, S.; Cecchi, L.; Severino, M.; Manfredi, M.; Ermini, G.; Macchia, D.; Capretti, S.; Campi, P. Severe Anaphylaxis to Royal Jelly Attributed to Cefonicid. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2007, 17, 281. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, R.J.; Rohan, A.; Straatmans, J.-A. Fatal Royal Jelly-Induced Asthma. Med. J. Aust. 1994, 160, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, A.; Rubira, N.; Nogueiras, C.; Guspi, R.; Baltasar, M.; Cadahia, A. Anaphylaxis caused by royal jelly. Allergol. Immunopathol. 1995, 23, 133–135. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, L.; Bartolome, B.; Moreno, A. Cross-Reactivity between Royal Jelly and Dermato-Phagoides Pteronyssinus. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2013, 1, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paola, F.; Pantalea, D.D.; Gianfranco, C.; Antonio, F.; Angelo, V.; Eustachio, N.; Elisabetta, D.L. Oral Allergy Syndrome in a Child Provoked by Royal Jelly. Case Rep. Med. 2014, 2014, 941248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, H.; Emori, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Hayashi, Y.; Nomoto, K. Suppression of Allergic Reactions by Royal Jelly in Association with the Restoration of Macrophage Function and the Improvement of Th1/Th2 Cell Responses. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2001, 1, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guendouz, M.; Haddi, A.; Grar, H.; Kheroua, O.; Saidi, D.; Kaddouri, H. Preventive Effects of Royal Jelly against Anaphylactic Response in a Murine Model of Cow’s Milk Allergy. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 2145–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-T.; Fan, J.-K.; Chen, X.; Que, S.-Y.; Zhang, R.-X.; Xie, Y.-Y.; Zhou, T.-C.; Ji, K.; Zhao, Z.-F.; Chen, J.-J. Royal Jelly Acid Inhibits NF-κB Signaling by Regulating H3 Histone Lactylation to Alleviate IgE-Mediated Mast Cell Activation and Allergic Inflammation. Phytomedicine 2025, 148, 157344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Fukase, T.; Yamazaki, M.; Watanabe, H.; Ebina, K. Royal Jelly-Derived Two Compounds, 10-Hydroxy-2-Decenoic Acid and a Biotinylated Royalisin-Related Peptide, Alleviate Anaphylactic Hypothermia In Vivo. J. Biol. Act. Prod. Nat. 2022, 12, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, I.; Taniguchi, Y.; Kunikata, T.; Kohno, K.; Iwaki, K.; Ikeda, M.; Kurimoto, M. Major Royal Jelly Protein 3 Modulates Immune Responses in Vitro and in Vivo. Life Sci. 2003, 73, 2029–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosmilah, M.; Shahnaz, M.; Patel, G.; Lock, J.; Rahman, D.; Masita, A.; Noormalin, A. Characterization of major allergens of royal jelly Apis mellifera. Trop. Biomed. 2008, 25, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matuszewska, E.; Matysiak, J.; Rosiński, G.; Kędzia, E.; Ząbek, W.; Zawadziński, J.; Matysiak, J. Mining the Royal Jelly Proteins: Combinatorial Hexapeptide Ligand Library Significantly Improves the MS-Based Proteomic Identification in Complex Biological Samples. Molecules 2021, 26, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, C.; Senna, G.E.; Gatti, B.; Feligioni, M.; Riva, G.; Bonadonna, P.; Dama, A.R.; Canonica, G.W.; Passalacqua, G. Allergic Reactions to Honey and Royal Jelly and Their Relationship with Sensitization to Compositae. Allergol. Immunopathol. 1998, 26, 288–290. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.M.; Rocha, B.; Moreira, M.M.; Delerue-Matos, C.; das Neves, J.; Rodrigues, F. Biological Activity and Chemical Composition of Propolis Extracts with Potential Use in Vulvovaginal Candidiasis Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdock, G.A. Review of the Biological Properties and Toxicity of Bee Propolis (Propolis). Food Chem. Toxicol. 1998, 36, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagh, V.D. Propolis: A Wonder Bees Product and Its Pharmacological Potentials. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 2013, 308249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oršolić, N. Allergic Inflammation: Effect of Propolis and Its Flavonoids. Molecules 2022, 27, 6694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maicelo-Quintana, J.L.; Reyna-Gonzales, K.; Balcázar-Zumaeta, C.R.; Auquiñivin-Silva, E.A.; Castro-Alayo, E.M.; Medina-Mendoza, M.; Cayo-Colca, I.S.; Maldonado-Ramirez, I.; Silva-Zuta, M.Z. Potential Application of Bee Products in Food Industry: An Exploratory Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münstedt, K.; Hellner, M.; Hackethal, A.; Winter, D.; Von Georgi, R. Contact Allergy to Propolis in Beekeepers. Allergol. Immunopathol. 2007, 35, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budimir, V.; Brailo, V.; Alajbeg, I.; Vučićević Boras, V.; Budimir, J. Allergic Contact Cheilitis and Perioral Dermatitis Caused by Propolis: Case Report. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2012, 20, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gulbahar, O.; Ozturk, G.; Erdem, N.; Kazandi, A.C.; Kokuludag, A. Psoriasiform Contact Dermatitis Due to Propolis in a Beekeeper. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005, 94, 509–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-J.; Lin, J.-L.; Yang, C.-W.; Yu, C.-C. Acute Renal Failure Induced by a Brazilian Variety of Propolis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2005, 46, e125–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezei, D.; Németh, D.; Temesvári, E.; Pónyai, G. A new-old allergen: Propolis contact hypersensitivity 1992–2021. Orvosi Hetil. 2022, 163, 1559–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antelmi, A.; Trave, I.; Gallo, R.; Cozzani, E.; Parodi, A.; Bruze, M.; Svedman, C. Prevalence of Contact Allergy to Propolis—Testing With Different Propolis Patch Test Materials. Contact Dermat. 2025, 92, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BasistaSołtys, K. Allergy to Propolis in Beekeepers-A Literature Review. Occup. Med. Health Aff. 2013, 1, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, Y.; Maloh, J.; Natarelli, N.; Gunt, H.B.; Tristani, E.; Sivamani, R.K. A Review of the Use of Beeswax in Skincare. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 2166–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.F.; Mousavi, Z.; McClements, D.J. Beeswax: A Review on the Recent Progress in the Development of Superhydrophobic Films/Coatings and Their Applications in Fruits Preservation. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, F.; Cilia, G.; Turchi, B.; Felicioli, A. Beeswax: A Minireview of Its Antimicrobial Activity and Its Application in Medicine. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2016, 9, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyman, G.S.A.; Tang, M.; Inerot, A.; Osmancevic, A.; Malmberg, P.; Hagvall, L. Contact Allergy to Beeswax and Propolis among Patients with Cheilitis or Facial Dermatitis. Contact Dermat. 2019, 81, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrebi, N.E.; Svečnjak, L.; Horvatinec, J.; Renault, V.; Rortais, A.; Cravedi, J.-P.; Saegerman, C. Adulteration of Beeswax: A First Nationwide Survey from Belgium. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Beeswax (E 901) as a glazing agent and as carrier for flavours-Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Food additives, Flavourings, Processing aids and Materials in Contact with Food (AFC). EFSA J. 2007, 5, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, S.M.; English, J.S. Occupational Contact Dermatitis from Propolis in a Dental Technician. Contact Dermat. 2007, 56, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpara, S.; Wilkinson, M.S.; King, C.M.; Gawkrodger, D.J.; English, J.S.C.; Statham, B.N.; Green, C.; Sansom, J.E.; Chowdhury, M.M.U.; Horne, H.L.; et al. The Importance of Propolis in Patch Testing–a Multicentre Survey. Contact Dermat. 2009, 61, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekky, A.E.; El-Barkey, N.M.; Abd El Halim, H.M.; Nasser, S.A.; Mahmoud, N.N.; Zahra, A.A.; Nasr-Eldin, M.A. Exploring the Potential of Hydro Alcoholic Crude Extract of Beeswax as Antibacterial Antifungal Antiviral Antiinflammatory and Antioxidant Agent. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska-Mach, E.; Packi, K.; Rzetecka, N.; Wieliński, W.; Kokot, Z.J.; Kowalczyk, D.; Matysiak, J. Insights into the Nutritional Value of Honeybee Drone Larvae (Apis Mellifera) through Proteomic Profiling. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiel, L.; Wind, C.; Ulmer, M.; Braun, P.G.; Koethe, M. Honey Bee Drone Brood Used as Food. Ernahr. Umsch. 2022, 69, 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, M.D. Nutrient Composition of Bee Brood and Its Potential as Human Food. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2007, 44, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B.; Jung, C. Honey Bees and Their Brood: A Potentially Valuable Resource of Food, Worthy of Greater Appreciation and Scientific Attention. J. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 45, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoevesandt, J.; Trautmann, A. Freshly Squeezed: Anaphylaxis Caused by Drone Larvae Juice. Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 50, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletta, F.; Ridolo, E.; Ottoni, M.; Barone, A.; Delfino, D.; Folli, C.; Tedeschi, T. Edible Insects and Allergenic Potential: An Observational Study About In Vitro IgE-Reactivity to Recombinant Pan-Allergens of the Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia Illucens) in Patients Sensitized to Crustaceans and Mites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premrov Bajuk, B.; Zrimšek, P.; Kotnik, T.; Leonardi, A.; Križaj, I.; Jakovac Strajn, B. Insect Protein-Based Diet as Potential Risk of Allergy in Dogs. Animals 2021, 11, 1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, E.; Dżugan, M. Drone Brood Homogenate as Natural Remedy for Treating Health Care Problem: A Scientific and Practical Approach. Molecules 2020, 25, 5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbarić, A.; Saftić Martinović, L.; Marijanović, Z.; Juretić, L.; Jurič, A.; Petrović, D.; Šoljić, V.; Gobin, I. Integrated Chemical and Biological Evaluation of Linden Honeydew Honey from Bosnia and Herzegovina: Composition and Cellular Effects. Foods 2025, 14, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, K.; Majie, A.; Jha, B.; Chatterjee, A.; Lim, W.M.; Gorain, B. Comparative Physicochemical, Microbiological, Pharmacological, and Toxicological Evaluations of Different Varieties of Honey Targeting Wound Repairment. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2025, 65, 103544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, S.D.A.; Baird, S.K. Honey Is Cytotoxic towards Prostate Cancer Cells but Interacts with the MTT Reagent: Considerations for the Choice of Cell Viability Assay. Food Chem. 2018, 241, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badria, F.; Fathy, H.; Fatehe, A.; Elimam, D.; Ghazy, M. Evaluate the Cytotoxic Activity of Honey, Propolis, and Bee Venom from Different Localities in Egypt against Liver, Breast, and Colorectal Cancer. J. Apither. 2017, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Olivo, L.A.; Paz-González, V. Screening of Biological Activities Present in Honeybee (Apis Mellifera) Royal Jelly. Toxicol. In Vitro 2005, 19, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, S.N.M.; Ramakreshnan, L.; Fong, C.S.; Wahab, R.A.; Rasad, M.S.B.A. In-Vitro Cytotoxicity of Trigona Itama Honey against Human Lung Adenocarcinoma Epithelial Cell Line (A549). Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2019, 30, 100955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustiawan, P.M.; Puthong, S.; Arung, E.T.; Chanchao, C. In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Indonesian Stingless Bee Products against Human Cancer Cell Lines. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arung, E.T.; Ramadhan, R.; Khairunnisa, B.; Amen, Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Nagata, M.; Kusuma, I.W.; Paramita, S.; Sukemi; Yadi; et al. Cytotoxicity Effect of Honey, Bee Pollen, and Propolis from Seven Stingless Bees in Some Cancer Cell Lines. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 7182–7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, J.F.; dos Santos, U.P.; Macorini, L.F.B.; de Melo, A.M.M.F.; Balestieri, J.B.P.; Paredes-Gamero, E.J.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; de Picoli Souza, K.; dos Santos, E.L. Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activities of Propolis from Melipona Orbignyi (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 65, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysin, F. Royal Jelly’s Strong Selective Cytotoxicity Against Lung Malignant Cells and Macromolecular Alterations in Cells Observed by FTIR Spectroscopy. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2025, 25, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnomasy, S.; Shehri, Z.; Shehri, Z.; Shehri, Z. Anti-Cancer and Cell Toxicity Effects of Royal Jelly and Its Cellular Mechanisms against Human Hepatoma Cells. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2022, 18, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusal, H.; Bozdayı, M.A.; Yigit Dumrul, H.K.; Tarakçıoğlu, M.S.; Taşkın, A. Investigation of Apoptosis-Mediated Cytotoxic Effects of Royal Jelly on HL-60 Cells. J. Anatol. Environ. Anim. Sci. 2024, 9, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervişoğlu, G.; Çobanoğlu, D.N.; Yelkovan, S.; Karahan, D.; Çakir, Y.; KoçyiğiT, S. Comprehensive Study on BeeBread: Palynological Analysis, Chemical Composition, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activities. Int. J. Second. Metab. 2022, 9, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonamigo, T.; Campos, J.F.; Oliveira, A.S.; Torquato, H.F.V.; Balestieri, J.B.P.; Cardoso, C.A.L.; Paredes-Gamero, E.J.; Souza, K.d.P.; dos Santos, E.L. Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activity of Propolis of Plebeia Droryana and Apis Mellifera (Hymenoptera, Apidae) from the Brazilian Cerrado Biome. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teerasripreecha, D.; Phuwapraisirisan, P.; Puthong, S.; Kimura, K.; Okuyama, M.; Mori, H.; Kimura, A.; Chanchao, C. In Vitro Antiproliferative/Cytotoxic Activity on Cancer Cell Lines of a Cardanol and a Cardol Enriched from Thai Apis Mellifera Propolis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matysiak, J.; Matuszewska, E.; Packi, K.; Klupczyńska-Gabryszak, A. Diagnosis of Hymenoptera Venom Allergy: State of the Art, Challenges, and Perspectives. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2170, Correction in Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Yanagida, N.; Ebisawa, M. How to Diagnose Food Allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 18, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhawar, N.; Gonzalez-Estrada, A. Honey-Induced Anaphylaxis in an Adult. QJM Int. J. Med. 2022, 115, 325–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinson, E.; Ocampo, C.; Liao, C.; Nguyen, S.; Dinh, L.; Rodems, K.; Whitters, E.; Hamilton, R.G. Cross-Reactive Carbohydrate Determinant Interference in Cellulose-Based IgE Allergy Tests Utilizing Recombinant Allergen Components. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ree, R.; Cabanes-Macheteau, M.; Akkerdaas, J.; Milazzo, J.-P.; Loutelier-Bourhis, C.; Rayon, C.; Villalba, M.; Koppelman, S.; Aalberse, R.; Rodriguez, R.; et al. β(1,2)-Xylose and α(1,3)-Fucose Residues Have a Strong Contribution in IgE Binding to Plant Glycoallergens. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 11451–11458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, F. The Role of Protein Glycosylation in Allergy. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2006, 142, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commins, S.P. Carbohydrates as Allergens. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014, 15, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vezir, E.; Kaya, A.; Toyran, M.; Azkur, D.; Dibek Mısırlıoğlu, E.; Kocabaş, C.N. Anaphylaxis/Angioedema Caused by Honey Ingestion. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014, 35, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, H.; Mowitz, M.; Bruze, M.; Engfeldt, M.; Isaksson, M.; Svedman, C. A Comparative Study between the Two Patch Test Systems Finn Chambers and Finn Chambers AQUA. Contact Dermat. 2021, 84, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calamelli, E.; Liotti, L.; Beghetti, I.; Piccinno, V.; Serra, L.; Bottau, P. Component-Resolved Diagnosis in Food Allergies. Medicina 2019, 55, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.C.; Simons, E.; Rudders, S.A. Epinephrine in the Management of Anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 1186–1195, Correction in J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroody, F.M.; Naclerio, R.M. Antiallergic Effects of H1-Receptor Antagonists. Allergy 2000, 55, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraro, A.; Roberts, G.; Worm, M.; Bilò, M.B.; Brockow, K.; Fernández Rivas, M.; Santos, A.F.; Zolkipli, Z.Q.; Bellou, A.; Beyer, K.; et al. Anaphylaxis: Guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Allergy 2014, 69, 1026–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frew, A.J. 86—Glucocorticoids. In Clinical Immunology, 5th ed.; Rich, R.R., Fleisher, T.A., Shearer, W.T., Schroeder, H.W., Frew, A.J., Weyand, C.M., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1165–1175.e1. ISBN 978-0-7020-6896-6. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R.L.; Li, J.T.C.; Nicklas, R.A.; Sadosty, A.T. Emergency Department Diagnosis and Treatment of Anaphylaxis: A Practice Parameter. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014, 113, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurashi, W.; Ellis, A.K. Do Corticosteroids Prevent Biphasic Anaphylaxis? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2017, 5, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahali, Y. Allergy after Ingestion of Bee-Gathered Pollen: Influence of Botanical Origins. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015, 114, 250–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecoraro, L.; Flore, A.I.; Dalle Carbonare, L.; Piacentini, G.; Pietrobelli, A. Honey and Children: Only a Grandma’s Panacea or a Real Useful Tool? Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 72, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, I.M.; Beiler, J.; McMonagle, A.; Shaffer, M.L.; Duda, L.; Berlin, C.M. Effect of Honey, Dextromethorphan, and No Treatment on Nocturnal Cough and Sleep Quality for Coughing Children and Their Parents. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, E.; Mulhauser, B.; Mulot, M.; Mutabazi, A.; Glauser, G.; Aebi, A. A Worldwide Survey of Neonicotinoids in Honey. Science 2017, 358, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, M.; Sütçü, M.; Kılıç, Ö.; Gül, D.; Tural Kara, T.; Akkoç, G.; Baktır, A.; Bozdemir, Ş.E.; Özgür Gündeşlioğlu, Ö.; Yıldız, F.; et al. Propolis as a Treatment Option for Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (HFMD) in Children: A Prospective Randomized Clinical Study. Children 2025, 12, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oršolić, N.; Jazvinšćak Jembrek, M. Royal Jelly: Biological Action and Health Benefits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahran, A.M.; Elsayh, K.I.; Saad, K.; Eloseily, E.M.A.; Osman, N.S.; Alblihed, M.A.; Badr, G.; Mahmoud, M.H. Effects of Royal Jelly Supplementation on Regulatory T Cells in Children with SLE. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 32963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strant, M.; Yücel, B.; Topal, E.; Puscasu, A.M.; Margaoan, R.; Varadi, A. Use of Royal Jelly as Functional Food on Human and Animal Health. Hayvansal Üretim 2019, 60, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouacha, M.; Ayed, H.; Grara, N. Honey Bee as Alternative Medicine to Treat Eleven Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Causing Urinary Tract Infection during Pregnancy. Sci. Pharm. 2018, 86, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatami, R.; Soltani, N.; Forouzideh, N.; Kazemi Robati, A.; Tavakolizadeh, M. Vaginal Honey as an Adjuvant Therapy for Standard Antibiotic Protocol of Cervicitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Res. J. Pharmacogn. 2022, 9, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrida, A.; Astuti, A.; Leli, L.; Saad, R. Effect of Honey to Levels Hemoglobin and Levels of 8-Hydroxy-2-Deoxyguanosin (8-Ohdg) in Pregnant Women with Anemia. J. Asian Multicult. Res. Med. Health Sci. Study 2022, 3, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulyani, Y.; Sari, D.N. The Effect of Dragon Fruit Juice and Honey On The Improvement of Pregnant Women’s Hb. Str. J. Ilm. Kesehat. 2020, 9, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianturi, M.I.B.; Sinaga, E.; Batubara, K. The Effect Of Honey Administration On Hemoglobin Levels Of Pregnant Women Trimester II. J. EduHealth 2022, 13, 1051–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Apnita Sari, K.; Sandhika, W.; Hardianto, G. Effect of Giving Propolis Extract to Pregnant Women with Bacterial Vaginosis. Indones. Midwifery Health Sci. J. 2023, 7, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikri, A.M.; Sulaeman, A.; Marliyati, S.A.; Fahrudin, M.; Handharyani, E. Effect of Propolis on Maternal Toxicity. Pharm. Sci. Asia 2021, 48, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, J.W.; Fasitasari, M.; Zulaikhah, S.T. Effects of Propolis Extract Supplementation during Pregnancy on Stress Oxidative and Pregnancy Outcome: Levels of Malondialdehyde, 8-Oxo-2â€2-Deoxogunosine, Maternal Body Weight, and Number of Fetuses. J. Kedokt. Brawijaya 2021, 31, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, U.Z.; Bakar, A.B.A.; Mohamed, M. Propolis Improves Pregnancy Outcomes and Placental Oxidative Stress Status in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baky, M.H.; Abouelela, M.B.; Wang, K.; Farag, M.A. Bee Pollen and Bread as a Super-Food: A Comparative Review of Their Metabolome Composition and Quality Assessment in the Context of Best Recovery Conditions. Molecules 2023, 28, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanov, S. Royal Jelly, Bee Brood: Composition, Health, Medicine: A Review. Lipids 2011, 3, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mishima, S.; Suzuki, K.-M.; Isohama, Y.; Kuratsu, N.; Araki, Y.; Inoue, M.; Miyata, T. Royal Jelly Has Estrogenic Effects in Vitro and in Vivo. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 101, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basista, K.M.; Filipek, B. Allergy to Propolis in Polish Beekeepers. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2012, 29, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qayoom, M.; Hassan, I.; Jeelani, S. Prevalence, Pattern, Contact Sensitisers and Impact on Quality-of-Life of Occupational Dermatitis among Beekeepers in North India. Contact Dermat. 2025, 92, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münstedt, K. Heat Immersion Therapy—A New Approach for Contact Dermatitis to Propolis? Allergol. Immunopathol. 2014, 42, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M.; Kaminska, D.; Matuszewska, E.; Hołderna-Kedzia, E.; Rogacki, J.; Matysiak, J. Promising Antimicrobial Properties of Bioactive Compounds from Different Honeybee Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzetecka, N.; Matuszewska, E.; Plewa, S.; Matysiak, J.; Klupczynska-Gabryszak, A. Bee Products as Valuable Nutritional Ingredients: Determination of Broad Free Amino Acid Profiles in Bee Pollen, Royal Jelly, and Propolis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 126, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska, E.; Klupczyńska-Gabryszak, A.; Plewa, S.; Rzetecka, N.; Packi, K.; Mohd, H.; Michniak-Kohn, B.; Matysiak, J. Application of Modern Analytical Techniques in the Analysis of Complex Matrices of Natural Origin on the Example of Honeybee Venom. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2023, 80, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, P.; Wu, Y.; He, Q. Recent Advances in Analytical Techniques for the Detection of Adulteration and Authenticity of Bee Products—A Review. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2021, 38, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bee Product | Primary Mechanism | Main Clinical Manifestation | Known/Suspected Allergens | Notes on Cross-Reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honey | Type I (IgE-mediated) | Anaphylaxis, urticaria, angioedema, gastrointestinal symptoms | Bee origin: Major Royal Jelly Protein 1 (MRJP1) Plant origin: Pollen proteins (e.g., from Asteraceae or Compositae families) | Strong cross-reactivity with airborne pollens (Pollen-Food Allergy Syndrome) |

| Bee Pollen | Type I (IgE-mediated) | Anaphylaxis | Pan-allergens: calmodulins, profilin, Specifics: Bnm1, Sal k 2, MetE | Highly dependent on botanical origin. Frequent cross-reactivity with plant pollens (weeds, grasses, trees) |

| Bee Bread | Type I (IgE-mediated) | - | Similar profile to BP, but potentially modified by fermentation | Lactic acid fermentation may degrade some allergenic epitopes, potentially lowering allergenicity compared to raw pollen |

| Royal Jelly | Type I (IgE-mediated) | Anaphylaxis, asthma, contact dermatitis | Major Royal Jelly Proteins, in particular: MRJP1, MRJP2, MRJP3 Others: venom acid phosphatase Acph-1-like, venom serine protease 34, icarapin variant 2 precursor | Cross-reactivity observed with honeybee venom and environmental allergens (dust mites, crab, cockroach) |

| Propolis | Type IV (T-cell-mediated) Type I (IgE-mediated) | Allergic contact dermatitis | Caffeates: 3-methyl-2-butenyl caffeate, phenylethyl caffeate, geranyl caffeate, benzyl caffeate, Others: Ferulic acid, tectochrysin, benzyl cinnamate, methyl cinnamate | Cross-reactivity with Peru balsam, rosin, turpentine, essential oils, and various fragrances |

| Beeswax | Type IV (T-cell-mediated) | Contact dermatitis | Contaminants: mainly caffeic acid derivatives | Pure beeswax is generally inert; reactions are usually due to propolis impurities remaining in unrefined wax |

| Bee Brood | Type I (IgE-mediated) | Anaphylaxis | Bee origin: MRJP Pan-allergens: arginine kinase, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, thioredoxin, and alpha-glucosidase | Risk of cross-reactivity with other honeybee products |

| Product | Frequency and Risk | Severity and Clinical Picture | High-Risk Populations | Diagnostic Approach | Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honey | Rare incidence, though widely consumed | Mild to severe; ranges from oral itching to systemic anaphylaxis and collapse | Individuals with atopy, specifically pollen allergies (Asteraceae) or food allergies | sIgE measurement, skin-prick test (SPT) (often prick-to-prick), component-resolved diagnostics (CRD) | Strict avoidance, epinephrine (adrenaline) for anaphylaxis; antihistamines for mild cutaneous symptoms |

| Bee Pollen | Uncommon, but the risk increases with atopy | Severe; high risk of anaphylaxis, bronchoconstriction, and angioedema within minutes of ingestion | Patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and pollen hypersensitivity | SPT with pollen extracts, sIgE | Discontinuation of supplements, emergency epinephrine auto-injector for sensitised individuals |

| Bee Bread | Very rare, considered safer than raw bee pollen | Mild; no anaphylactic reactions reported to date; mainly mild gastrointestinal or cutaneous symptoms | Individuals sensitive to raw bee pollen | Similarly to bee pollen; oral food challenge may be considered under supervision | Avoidance if pollen allergy is confirmed |

| Royal Jelly | Rare, but may be dangerous | Severe; history of fatal and near-fatal anaphylaxis; acute asthma attacks | Asthmatics (highest risk), individuals with atopic dermatitis or honeybee venom allergy | SPT, sIgE, basophil activation test (BAT) | Strict avoidance for asthmatics/atopics; epinephrine for acute reactions |

| Propolis | Common; related to occupational risk | Mild to moderate; primarily delayed contact dermatitis (eczema, swelling); systemic reactions are rare | Beekeepers (occupational exposure), users of natural cosmetics and biocides | Patch testing (gold standard for type IV hypersensitivity) | Topical corticosteroids for dermatitis; avoidance of propolis-containing cosmetics/lozenges |

| Beeswax | Rare, often linked to impurity | Mild; localised contact dermatitis, cheilitis, or fingertip eczema | Individuals already sensitised to propolis or fragrances | Patch testing (differentiating between yellow and white wax) | Avoidance of unrefined wax products; use of purified synthetic alternatives |

| Bee Brood | Rare—emerging novel food | Moderate; potential for anaphylaxis due to pan-allergens | Individuals allergic to crustaceans (shellfish), dust mites, or mealworms | sIgE (potential cross-reactivity) | Avoidance of edible insects; epinephrine for accidental ingestion reactions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matuszewska-Mach, E.; Borysewicz, P.; Królak, J.; Juzwa-Sobieraj, M.; Matysiak, J. Ensuring the Safe Use of Bee Products: A Review of Allergic Risks and Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12074. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412074

Matuszewska-Mach E, Borysewicz P, Królak J, Juzwa-Sobieraj M, Matysiak J. Ensuring the Safe Use of Bee Products: A Review of Allergic Risks and Management. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12074. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412074

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatuszewska-Mach, Eliza, Paulina Borysewicz, Jan Królak, Magdalena Juzwa-Sobieraj, and Jan Matysiak. 2025. "Ensuring the Safe Use of Bee Products: A Review of Allergic Risks and Management" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12074. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412074

APA StyleMatuszewska-Mach, E., Borysewicz, P., Królak, J., Juzwa-Sobieraj, M., & Matysiak, J. (2025). Ensuring the Safe Use of Bee Products: A Review of Allergic Risks and Management. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12074. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412074