Synergistic Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training and Asparagus officinalis L. Root Extract Supplementation on Metabolic Regulation, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Overweight and Obese Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Baseline Participant Characteristics

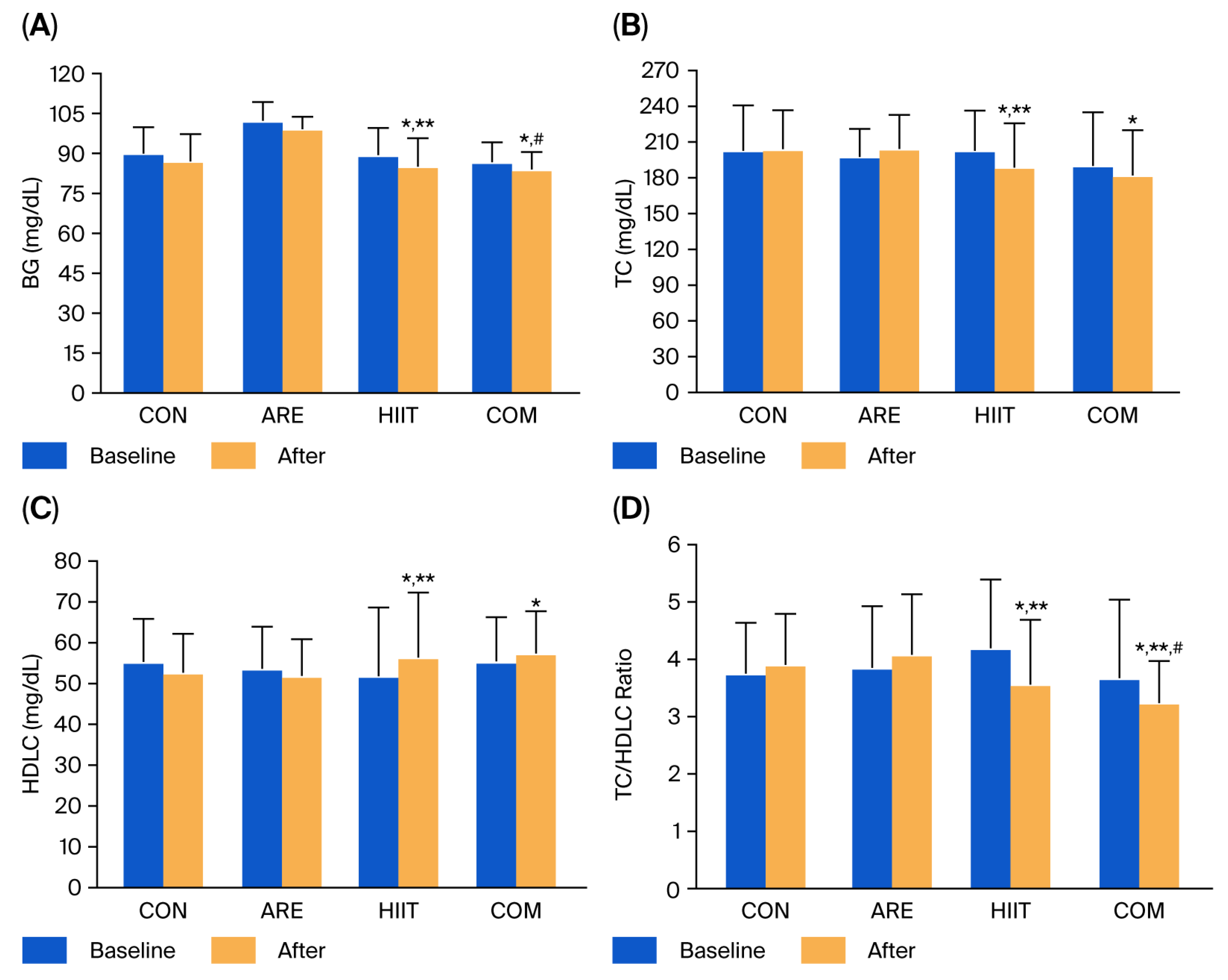

2.2. Blood Glucose and Lipid Profile

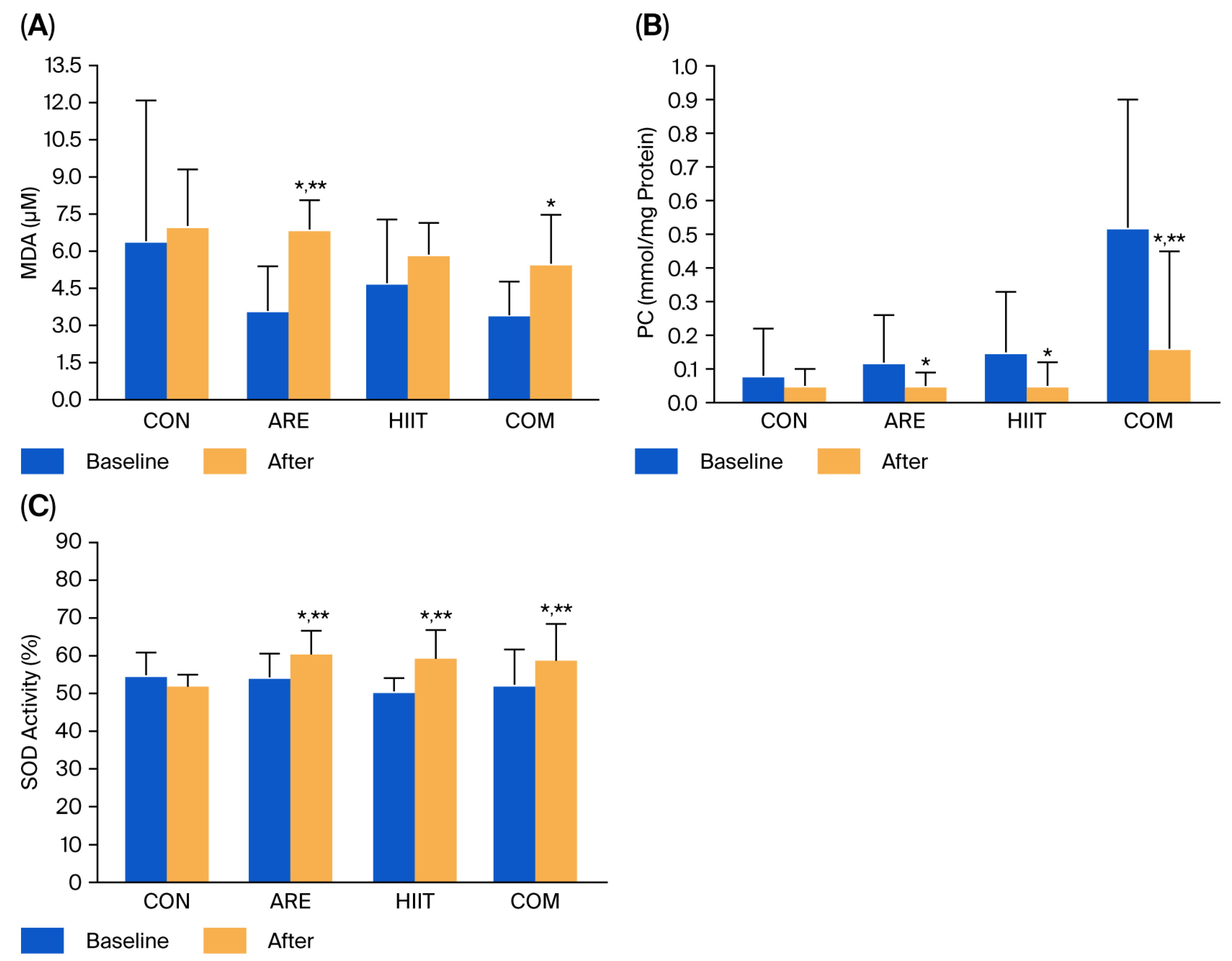

2.3. Oxidative Stress Markers

2.4. Inflammatory Biomarkers

2.5. White Blood Cell Counts

2.6. Liver Function Parameters

3. Discussion

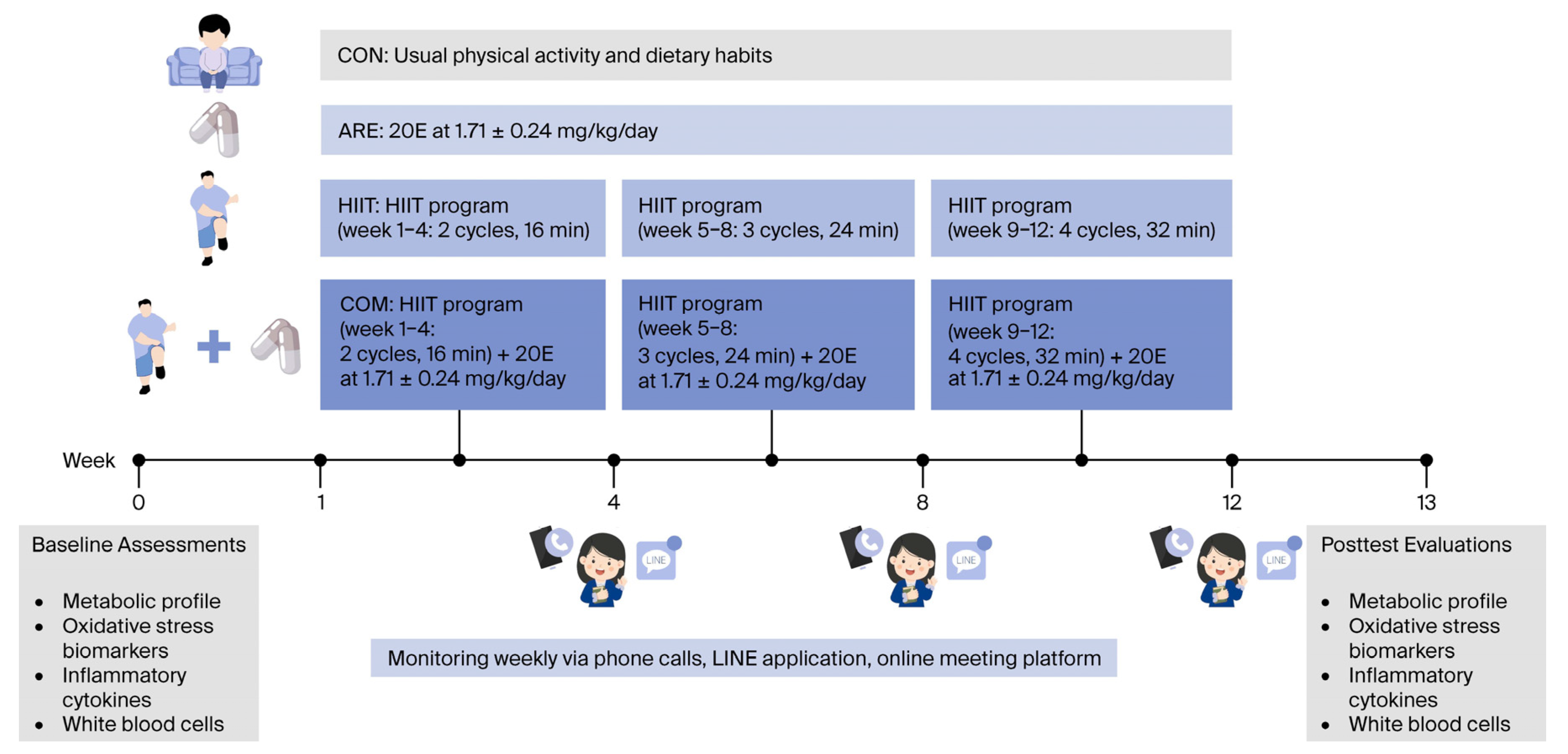

4. Materials and Methods

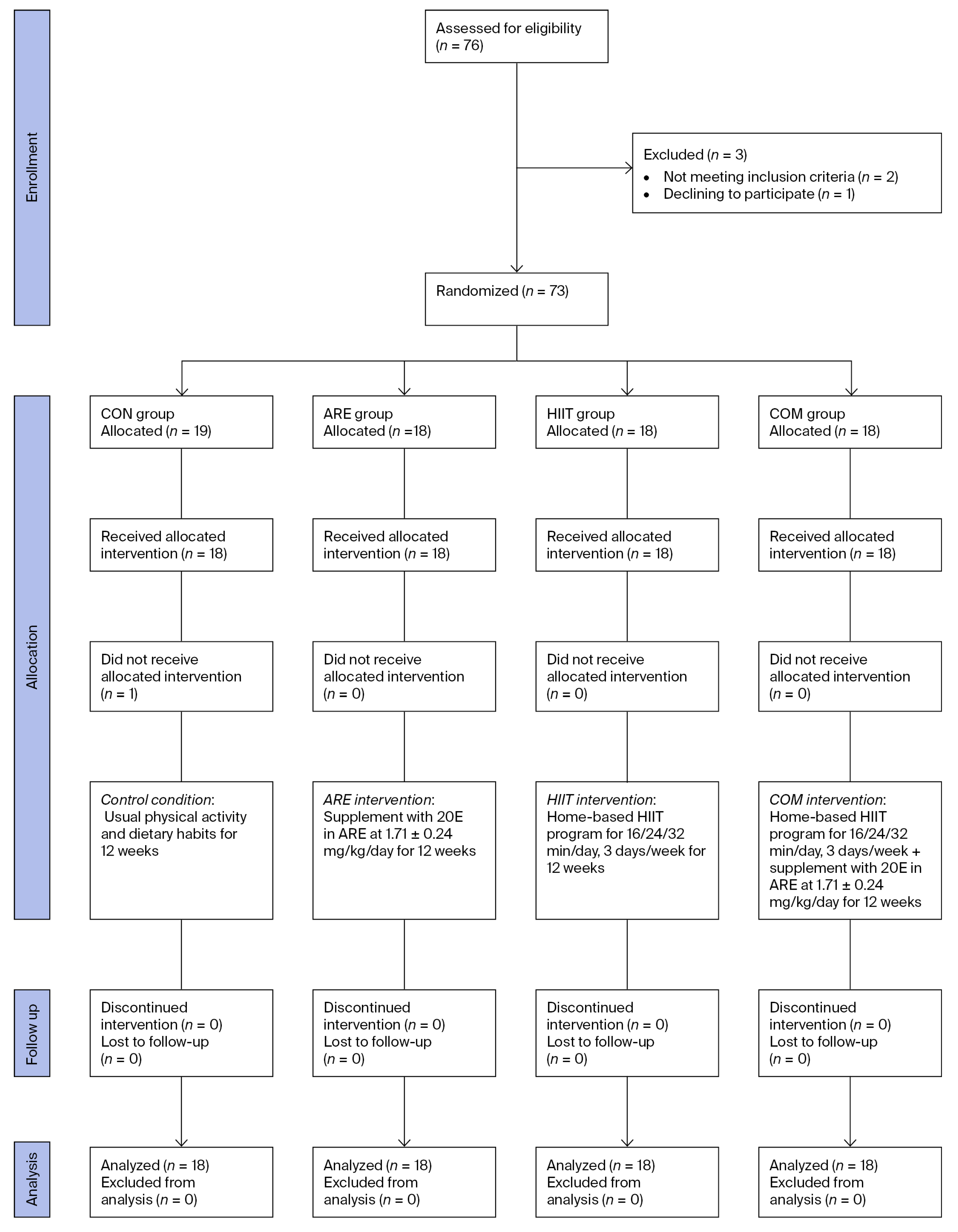

4.1. Study Design and Sample Size

4.2. Ethical Considerations and Informed Consent

4.3. Screening of Participants

4.4. Experimental Procedures

4.4.1. Randomization and Blinding

4.4.2. Experimental Protocols

4.5. HIIT Program

4.6. ARE Supplement

4.7. Study Outcomes and Measurements

4.7.1. Oxidative Stress Biomarker Analysis

4.7.2. Inflammatory Cytokine Analysis

4.7.3. WBC and Metabolic Profile Analysis

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 20E | 20-hydroxyecdysone |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase; |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of covariance |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| ARE | Asparagus root extract |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase; |

| BG | Blood glucose |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CAT | Catalase |

| COM | Combined intervention |

| CON | Control |

| DNPH | Dinitrophenylhydrazine |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| GLUT4 | Glucose transporter 4 |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | Glutathione disulfide |

| HCL | Hydrochloric acid |

| HDLC | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HIIT | High-intensity interval training |

| HMG-CoA | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LDLC | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| M2 | Alternatively activated macrophages |

| MARK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor- kappa B |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PC | Protein carbonyl |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α |

| PPAR-α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TBAR | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substance |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TCA | Trichloroacetic acid |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| Th2 | T helper 2 |

| TNF-α | Tumor-necrosis factor-alpha |

| VLDLC | Very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| WBC | White blood cell |

References

- Ahmed, S.K.; Mohammed, R.A. Obesity: Prevalence, causes, consequences, management, preventive strategies and future research directions. Metabol. Open 2025, 27, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, P.; Jain, S.K. Obesity, Oxidative Stress, Adipose Tissue Dysfunction, and the Associated Health Risks: Causes and Therapeutic Strategies. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2015, 13, 423–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, A.; Korac, A.; Buzadzic, B.; Otasevic, V.; Stancic, A.; Daiber, A.; Korac, B. Redox implications in adipose tissue (dys)function--A new look at old acquaintances. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asatiani, N.; Sapojnikova, N.; Kartvelishvili, T.; Asanishvili, L.; Sichinava, N.; Chikovani, Z. Blood Catalase, Superoxide Dismutase, and Glutathione Peroxidase Activities in Alcohol- and Opioid-Addicted Patients. Medicina 2025, 61, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; Gu, N.; Chen, L.; Zhu, L.; Yang, L.; Pang, L.; Guo, X.; Ji, C.; et al. IL-6 and TNF-α induced obesity-related inflammatory response through transcriptional regulation of miR-146b. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014, 34, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atakan, M.M.; Li, Y.; Koşar, Ş.N.; Turnagöl, H.H.; Yan, X. Evidence-Based Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training on Exercise Capacity and Health: A Review with Historical Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reljic, D. High-Intensity Interval Training as Redox Medicine: Targeting Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Adaptations in Cardiometabolic Disease Cohorts. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouerghi, N.; Fradj, M.K.B.; Duclos, M.; Bouassida, A.; Feki, M.; Weiss, K.; Knechtle, B. Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training on Selected Adipokines and Cardiometabolic Risk Markers in Normal-Weight and Overweight/Obese Young Males-A Pre-Post Test Trial. Biology 2022, 11, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, C.; He, H. Effect of Exercise Training on Body Composition and Inflammatory Cytokine Levels in Overweight and Obese Individuals: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 921085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegiou, E.; Mumm, R.; Acharya, P.; de Vos, R.C.H.; Hall, R.D. Green and White Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis): A Source of Developmental, Chemical and Urinary Intrigue. Metabolites 2019, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denben, B.; Sripinyowanich, S.; Ruangthai, R.; Phoemsapthawee, J. Beneficial Effects of Asparagus officinalis Extract Supplementation on Muscle Mass and Strength following Resistance Training and Detraining in Healthy Males. Sports 2023, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.J.; Dai, J.Q.; Fang, J.G.; Ma, L.P.; Hou, L.F.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.L. Antioxidative and free radical scavenging effects of ecdysteroids from Serratula strangulata. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2002, 80, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, M.; Mamadalieva, N.Z.; Chauhan, A.K.; Kang, S.C. α-Ecdysone suppresses inflammatory responses via the Nrf2 pathway in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 73, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalán, R.E.; Martinez, A.M.; Aragones, M.D.; Miguel, B.G.; Robles, A.; Godoy, J.E. Alterations in rat lipid metabolism following ecdysterone treatment. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 1985, 81, 771–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibala, M.J.; Little, J.P.; Macdonald, M.J.; Hawley, J.A. Physiological adaptations to low-volume, high-intensity interval training in health and disease. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J.P.; Gillen, J.B.; Percival, M.E.; Safdar, A.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Punthakee, Z.; Jung, M.E.; Gibala, M.J. Low-volume high-intensity interval training reduces hyperglycemia and increases muscle mitochondrial capacity in patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 1554–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, M.S.; Little, J.P.; Tarnopolsky, M.A.; Myslik, F.; Gibala, M.J. Low-volume interval training improves muscle oxidative capacity in sedentary adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1849–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolati, S.; Namiranian, K.; Amerian, R.; Mansouri, S.; Arshadi, S.; Azarbayjani, M.A. The Effect of Curcumin Supplementation and Aerobic Training on Anthropometric Indices, Serum Lipid Profiles, C-Reactive Protein and Insulin Resistance in Overweight Women: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 2020, 29, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Yang, W.; Kiarasi, F. Polyphenol-Based Nutritional Strategies Combined with Exercise for Brain Function and Glioma Control: Focus on Epigenetic Modifications, Cognitive Function, Learning and Memory Processes. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongraykang, J.; Padkao, T.; Boonla, O.; Teethaisong, Y.; Roengrit, T.; Koowattanatianchai, S.; Prasertsri, P. Effects of Asparagus Powder Supplementation on Glycemic Control, Lipid Profile, and Oxidative Stress in Overweight and Obese Adults: An Exploratory Randomized Controlled Trial. Life 2025, 15, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjønna, A.E.; Lee, S.J.; Rognmo, Ø.; Stølen, T.O.; Bye, A.; Haram, P.M.; Loennechen, J.P.; Al-Share, Q.Y.; Skogvoll, E.; Slørdahl, S.A.; et al. Aerobic interval training versus continuous moderate exercise as a treatment for the metabolic syndrome: A pilot study. Circulation 2008, 118, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, H.S.; Sisson, S.B.; Short, K.R. The potential for high-intensity interval training to reduce cardiometabolic disease risk. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, D.I.; Adeniran, S.A.; Dikko, A.U.; Sayers, S.P. The effect of a high-intensity interval training program on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in young men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olas, B. A Review of the Pro-Health Activity of Asparagus officinalis L. and Its Components. Foods 2024, 13, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Lepe, M.A.; Olivas-Aguirre, F.J.; Gómez-Miranda, L.M.; Hernández-Torres, R.P.; Manríquez-Torres, J.J.; Ramos-Jiménez, A. Systematic Physical Exercise and Spirulina maxima Supplementation Improve Body Composition, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and Blood Lipid Profile: Correlations of a Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Trial. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, S.; Tadibi, V.; Hoseini, R. How combined aerobic training and pomegranate juice intake affect lipid profile? A clinical trial in men with type 2 diabetes. Biomed. Human Kinet. 2021, 13, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher-Wellman, K.; Bloomer, R.J. Acute exercise and oxidative stress: A 30 year history. Dyn. Med. 2009, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avloniti, A.; Chatzinikolaou, A.; Deli, C.K.; Vlachopoulos, D.; Gracia-Marco, L.; Leontsini, D.; Draganidis, D.; Jamurtas, A.Z.; Mastorakos, G.; Fatouros, I.G. Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress Responses in the Pediatric Population. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza-Silva, A.A.; Moreira, E.; de Melo-Marins, D.; Schöler, C.M.; de Bittencourt, P.I., Jr.; Laitano, O. High intensity interval training in the heat enhances exercise-induced lipid peroxidation, but prevents protein oxidation in physically active men. Temperature 2016, 3, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samjoo, I.A.; Safdar, A.; Hamadeh, M.J.; Raha, S.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. The effect of endurance exercise on both skeletal muscle and systemic oxidative stress in previously sedentary obese men. Nutr. Diabetes 2013, 3, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, A.M.; Pedersen, B.K. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2005, 98, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleeson, M.; Bishop, N.C.; Stensel, D.J.; Lindley, M.R.; Mastana, S.S.; Nimmo, M.A. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: Mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, D.; Chaudhary, M.; Mandotra, S.K.; Tuli, H.S.; Chauhan, R.; Joshi, N.C.; Kaur, D.; Dufossé, L.; Chauhan, A. Anti-inflammatory potential of quercetin: From chemistry and mechanistic insight to nanoformulations. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2025, 8, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mediavilla, V.; Crespo, I.; Collado, P.S.; Esteller, A.; Sánchez-Campos, S.; Tuñón, M.J.; González-Gallego, J. The anti-inflammatory flavones quercetin and kaempferol cause inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase, cyclooxygenase-2 and reactive C-protein, and down-regulation of the nuclear factor kappaB pathway in Chang Liver cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 557, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesekara, T.; Luo, J.; Xu, B. Critical review on anti-inflammation effects of saponins and their molecular mechanisms. Phytother. Res. 2024, 38, 2007–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanim, H.; Sia, C.L.; Abuaysheh, S.; Korzeniewski, K.; Patnaik, P.; Marumganti, A.; Chaudhuri, A.; Dandona, P. An antiinflammatory and reactive oxygen species suppressive effects of an extract of Polygonum cuspidatum containing resveratrol. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, E1–E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Gao, C.; Wang, H.; Ren, Y.; Li, J.; Li, M.; Du, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, J. Effects of dietary polyphenol curcumin supplementation on metabolic, inflammatory, and oxidative stress indices in patients with metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1216708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighatdoost, F.; Gholami, A.; Hariri, M. Effect of grape polyphenols on selected inflammatory mediators: A systematic review and meta-analysis randomized clinical trials. Excli J. 2020, 19, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radak, Z.; Chung, H.Y.; Koltai, E.; Taylor, A.W.; Goto, S. Exercise, oxidative stress and hormesis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2008, 7, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K. The Physiology of Optimizing Health with a Focus on Exercise as Medicine. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2019, 81, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirato, K.; Koda, T.; Takanari, J.; Sakurai, T.; Ogasawara, J.; Imaizumi, K.; Ohno, H.; Kizaki, T. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of ETAS®50 by Inhibiting Nuclear Factor-κB p65 Nuclear Import in Ultraviolet-B-Irradiated Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2018, 2018, 5072986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobhy, Y.; Mahgoub, S.; Abo-Zeid, Y.; Mina, S.A.; Mady, M.S. In-Vitro Cytotoxic and Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Asparagus Densiflorus Meyeri and its Phytochemical Investigation. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202400959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltani, N.; Marandi, S.M.; Kazemi, M.; Esmaeil, N. Combined All-Extremity High-Intensity Interval Training Regulates Immunometabolic Responses through Toll-Like Receptor 4 Adaptors and A20 Downregulation in Obese Young Females. Obes. Facts 2020, 13, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castillo, I.M.; Rueda, R.; Bouzamondo, H.; Aparicio-Pascual, D.; Valiño-Marques, A.; López-Chicharro, J.; Segura-Ortiz, F. Does Lifelong Exercise Counteract Low-Grade Inflammation Associated with Aging? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2025, 55, 675–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuraikhy, S.; Sellami, M.; Al-Amri, H.S.; Domling, A.; Althani, A.A.; Elrayess, M.A. Impact of Moderate Physical Activity on Inflammatory Markers and Telomere Length in Sedentary and Moderately Active Individuals with Varied Insulin Sensitivity. J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 16, 5427–5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Molofsky, A.B.; Liang, H.E.; Ricardo-Gonzalez, R.R.; Jouihan, H.A.; Bando, J.K.; Chawla, A.; Locksley, R.M. Eosinophils sustain adipose alternatively activated macrophages associated with glucose homeostasis. Science 2011, 332, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Nguyen, K.D.; Odegaard, J.I.; Cui, X.; Tian, X.; Locksley, R.M.; Palmiter, R.D.; Chawla, A. Eosinophils and type 2 cytokine signaling in macrophages orchestrate development of functional beige fat. Cell 2014, 157, 1292–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, N.P.; Gleeson, M.; Shephard, R.J.; Gleeson, M.; Woods, J.A.; Bishop, N.C.; Fleshner, M.; Green, C.; Pedersen, B.K.; Hoffman-Goetz, L.; et al. Position statement. Part one: Immune function and exercise. Exerc. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 17, 6–63. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, H.A.; Wood, L.G.; Williams, E.J.; Weaver, N.; Upham, J.W. Comparing the Effect of Acute Moderate and Vigorous Exercise on Inflammation in Adults with Asthma: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2022, 19, 1848–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes-Ferreira, R.; Brandao-Rangel, M.A.R.; Gibson-Alves, T.G.; Silva-Reis, A.; Souza-Palmeira, V.H.; Aquino-Santos, H.C.; Frison, C.R.; Oliveira, L.V.F.; Albertini, R.; Vieira, R.P. Physical Training Reduces Chronic Airway Inflammation and Mediators of Remodeling in Asthma. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2022, 2022, 5037553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viriyautsahakul, V.; Soontornmanokul, T.; Komolmit, P.; Jiamjarasrangsi, W.; Treeprasertsuk, S. What is the normal serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) value for Thai subjects with the low risk of liver diseases? Chulalongkorn Med. J. 2013, 57, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varra, F.N.; Varras, M.; Varra, V.K.; Theodosis-Nobelos, P. Mechanisms Linking Obesity with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs)-The Role of Oxidative Stress. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, M.C.; Subar, A.F.; Warthon-Medina, M.; Cade, J.E.; Burrows, T.; Golley, R.K.; Forouhi, N.G.; Pearce, M.; Holmes, B.A. Dietary assessment toolkits: An overview. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baecke, J.A.; Burema, J.; Frijters, J.E. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1982, 36, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalayondeja, C.; Jalayondeja, W.; Vachalathiti, R.; Bovonsunthonchai, S.; Sakulsriprasert, P.; Kaewkhuntee, W.; Bunprajun, T.; Upiriyasakul, R. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the Compendium of Physical Activity: Thai Translation and Content Validity. J. Med. Assoc. Thai 2015, 98, S53–S59. [Google Scholar]

- Dinan, L.; Dioh, W.; Veillet, S.; Lafont, R. 20-Hydroxyecdysone, from Plant Extracts to Clinical Use: Therapeutic Potential for the Treatment of Neuromuscular, Cardio-Metabolic and Respiratory Diseases. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padkao, T.; Prasertsri, P. The Impact of Modified Tabata Training on Segmental Fat Accumulation, Muscle Mass, Muscle Thickness, and Physical and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Overweight and Obese Participants: A Randomized Control Trial. Sports 2025, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padkao, T.; Prasertsri, P. Effects of High-Intensity Intermittent Training Combined with Asparagus officinalis Extract Supplementation on Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Function Parameters in Obese and Overweight Individuals: A Randomized Control Trial. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2025, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukongviriyapan, U.; Kukongviriyapan, V.; Pannangpetch, P.; Donpunha, W.; Sripui, J.; Sae-Eaw, A.; Boonla, O. Mamao Pomace Extract Alleviates Hypertension and Oxidative Stress in Nitric Oxide Deficient Rats. Nutrients 2015, 7, 6179–6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intakhiao, S.; Prakobkaew, N.; Buddhisa, S.; Boonla, O.; Teethaisong, Y.; Koowattanatianchai, S.; Prasertsri, P. Ameliorative Effects of Triphala Supplementation on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Individuals with Post-COVID-19 Condition: A Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. Glob. Adv. Integr. Med. Health 2025, 14, 27536130251385551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, R.W.; D’Orazio, P.; Fogh-Andersen, N.; Kuwa, K.; Külpmann, W.R.; Larsson, L.; Lewnstam, A.; Maas, A.H.; Mager, G.; Spichiger-Keller, U.; et al. IFCC recommendation on reporting results for blood glucose. Clin. Chim. Acta 2001, 307, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | CON (n = 18) | ARE (n = 18) | HIIT (n = 18) | COM (n = 18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female, n (%) | 5 (28)/13 (72) | 2 (11)/16 (89) | 5 (28)/13 (72) | 2 (11)/16 (89) |

| Age (years) | 21.61 ± 2.06 | 20.22 ± 1.93 | 20.72 ± 1.32 | 20.06 ± 2.01 |

| Overweight/obese, n (%) | 2 (11)/16 (89) | 5 (28)/13 (72) | 5 (28)/13 (72) | 5 (28)/13 (72) |

| Physical activity level | ||||

| - Sedentary, n (%) | 3 (17) | 3 (17) | 3 (17) | 1 (6) |

| - Active, n (%) | 11 (61) | 9 (50) | 12 (66) | 14 (78) |

| - Athletic, n (%) | 4 (22) | 6 (33) | 3 (17) | 3 (17) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| - Baseline | 29.10 ± 5.11 | 26.98 ± 2.97 | 29.13 ± 5.48 | 26.92 ± 2.50 |

| - After | 29.10 ± 4.87 | 27.44 ± 3.04 | 29.59 ± 5.65 | 27.19 ± 2.32 |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | ||||

| - Baseline | 46.04 ± 9.06 | 44.73 ± 9.60 | 46.85 ± 9.84 | 44.12 ±6.50 |

| - After | 45.82 ± 9.06 | 45.11 ± 10.12 | 47.24 ± 10.20 | 43.77 ± 6.28 |

| Fat mass (kg) | ||||

| - Baseline | 31.36 ± 10.23 | 26.70 ± 6.21 | 30.79 ±11.64 | 26.34 ± 5.26 |

| - After | 31.53 ± 9.62 | 27.60 ± 6.72 | 31.65 ± 11.85 | 27.42 ± 4.84 |

| Percent body fat | ||||

| - Baseline | 40.07 ± 7.38 | 37.44 ± 5.53 | 39.02 ± 8.98 | 37.37 ± 5.79 |

| - After | 40.44 ± 7.14 | 38.04 ± 5.64 | 39.54 ± 9.21 | 38.52 ± 5.10 |

| Daily energy intake (kcal/day) | ||||

| - Baseline | 2156 ± 218 | 2385 ± 215 | 2439 ± 218 | 2100 ± 150 |

| - After | 2326 ± 204 | 2043 ± 200 | 2334 ± 200 | 2274 ± 119 |

| Daily energy intake (kcal/day/kg) | ||||

| - Baseline | 28.86 ± 3.63 | 33.26 ± 2.89 | 36.13 ± 3.65 | 30.48 ± 2.14 |

| - After | 31.30 ± 3.57 | 28.75 ± 2.87 | 34.26 ± 2.54 | 33.36 ± 2.22 |

| Physical activity score | ||||

| - Baseline | 7.01 ± 1.07 | 7.46 ± 1.19 | 7.04 ± 0.99 | 6.86 ± 0.85 |

| - After | 6.96 ± 0.79 | 7.27 ± 0.99 | 7.31 ± 1.22 | 7.37 ± 1.20 |

| Parameters | CON (n = 18) | ARE (n = 18) | HIIT (n = 18) | COM (n = 18) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After | Baseline | After | Baseline | After | Baseline | After | |

| BG (mg/dL) | 89.94 ± 9.92 | 87.17 ± 10.08 | 102.33 ± 6.97 | 99.11 ± 4.78 | 89.33 ± 10.36 | 84.94 ± 10.90 *,** | 86.72 ± 7.41 | 83.94 ± 6.71 *,# |

| TC (mg/dL) | 202.50 ± 38.44 | 204.06 ± 32.44 | 197.61 ± 23.19 | 204.28 ± 28.38 | 202.61 ± 33.95 | 188.72 ± 37.25 *,** | 189.94 ± 45.16 | 182.11 ± 37.75 * |

| TG (mg/dL) | 111.00 ± 64.51 | 122.94 ± 68.63 | 109.66 ± 51.57 | 111.06 ± 51.16 | 119.83 ± 71.00 | 110.28 ± 47.43 | 94.50 ± 47.01 | 93.94 ± 43.70 |

| HDLC (mg/dL) | 55.27 ± 10.56 | 52.67 ± 9.58 | 53.61 ± 10.36 | 51.89 ± 9.04 | 51.83 ± 16.82 | 56.39 ± 15.91 *,** | 55.44 ± 10.88 | 57.39 ± 10.30 * |

| LDLC (mg/dL) | 135.88 ± 34.10 | 138.00 ± 29.34 | 131.77 ± 27.13 | 145.83 ± 30.31 * | 138.77 ± 28.66 | 139.72 ± 35.39 | 122.50 ± 44.30 | 121.17 ± 40.18 |

| VLDLC (mg/dL) | 22.27 ± 12.92 | 24.50 ± 13.74 | 21.88 ± 10.35 | 22.22 ± 10.12 | 24.00 ± 14.18 | 23.33 ± 9.35 | 18.94 ± 9.40 | 20.39 ± 9.09 |

| TC/HDLC ratio | 3.75 ± 0.89 | 3.90 ± 0.89 | 3.85 ± 1.08 | 4.08 ± 1.05 | 4.19 ± 1.20 | 3.56 ± 1.13 *,** | 3.67 ± 1.37 | 3.24 ± 0.73 *,**,# |

| LDLC/HDLC ratio | 2.53 ± 0.79 | 2.72 ± 0.86 | 2.62 ± 1.07 | 2.95 ± 1.06 * | 2.94 ± 1.11 | 2.72 ± 1.18 | 2.29 ± 0.90 | 2.17 ± 0.78 |

| ALT (U/L) | - | - | 19.47 ± 4.58 | 18.67 ± 12.12 | - | - | 16.36 ± 3.85 | 20.22 ± 11.27 |

| AST (U/L) | - | - | 23.83 ± 12.56 | 21.67 ± 4.98 | - | - | 21.61 ± 7.94 | 21.78 ± 5.63 |

| Parameters | CON (n = 18) | ARE (n = 18) | HIIT (n = 18) | COM (n = 18) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | After | Baseline | After | Baseline | After | Baseline | After | |

| Total white blood cell (×103 cells/mm3) | 7.64 ± 1.85 | 8.06 ± 1.58 | 7.43 ± 1.25 | 8.02 ± 1.27 | 7.48 ± 1.76 | 7.91 ± 1.59 | 7.23 ± 2.17 | 7.46 ± 2.01 |

| Neutrophils (×103 cells/mm3) | 4.23 ± 1.48 | 4.39 ± 1.02 | 3.98 ± 0.72 | 4.39 ± 1.23 | 4.02 ± 1.10 | 3.93 ± 1.52 | 4.12 ± 1.47 | 4.25 ± 1.45 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 54.40 ± 7.66 | 54.47 ± 6.12 | 53.52 ± 4.90 | 54.08 ± 7.46 | 53.37 ± 5.60 | 52.14 ± 7.28 | 56.59 ± 8.37 | 56.33 ± 7.67 |

| Eosinophils (cells/mm3) | 177 ± 137 | 209 ± 160 | 255 ± 165 | 311 ± 226 | 199 ± 153 | 188 ± 91 | 163 ± 73 | 179 ± 81# |

| Eosinophils (%) | 2.51 ± 1.95 | 2.66 ± 1.97 | 3.46 ± 2.34 | 3.95 ± 2.97 | 2.47 ± 1.39 | 2.33 ± 0.91 # | 2.28 ± 0.90 | 2.42 ± 1.02 |

| Basophils (cells/mm3) | 27 ± 14 | 30 ± 20 | 37 ± 14 | 34 ± 15 | 24 ± 8 | 28 ± 11 | 22 ± 18# | 25 ± 17 |

| Basophils (%) | 0.38 ± 0.20 | 0.38 ± 0.24 | 0.49 ± 0.15 | 0.43 ± 0.19 | 0.33 ± 0.11 | 0.36 ± 0.17 | 0.31 ± 0.20 | 0.36 ± 0.23 |

| Lymphocytes (×103 cells/mm3) | 2.72 ± 0.63 | 2.96 ± 0.84 | 2.73 ± 0.62 | 2.83 ± 0.51 | 2.75 ± 0.63 | 2.85 ± 0.95 | 2.52 ± 0.93 | 2.59 ± 0.81 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 36.43 ± 6.76 | 36.53 ± 5.78 | 36.79 ± 5.57 | 35.79 ± 6.37 | 37.25 ± 5.65 | 39.01 ± 7.08 | 34.82 ± 7.35 | 35.01 ± 7.17 |

| Monocytes (cells/mm3) | 478 ± 148 | 481 ± 137 | 426 ± 105 | 454 ± 101 | 451 ± 157 | 486 ± 126 | 409 ± 91 | 415 ± 70 |

| Monocytes (%) | 6.25 ± 1.19 | 5.96 ± 1.13 | 5.72 ± 0.95 | 5.74 ± 1.41 | 6.55 ± 1.63 | 6.16 ± 1.01 | 5.97 ± 1.84 | 5.87 ± 1.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prasertsri, P.; Padkao, T.; Boonla, O.; Buddhisa, S.; Prakobkaew, N.; Sripinyowanich, S.; Phoemsapthawee, J. Synergistic Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training and Asparagus officinalis L. Root Extract Supplementation on Metabolic Regulation, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Overweight and Obese Adults. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412054

Prasertsri P, Padkao T, Boonla O, Buddhisa S, Prakobkaew N, Sripinyowanich S, Phoemsapthawee J. Synergistic Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training and Asparagus officinalis L. Root Extract Supplementation on Metabolic Regulation, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Overweight and Obese Adults. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412054

Chicago/Turabian StylePrasertsri, Piyapong, Tadsawiya Padkao, Orachorn Boonla, Surachat Buddhisa, Nattaphol Prakobkaew, Siriporn Sripinyowanich, and Jatuporn Phoemsapthawee. 2025. "Synergistic Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training and Asparagus officinalis L. Root Extract Supplementation on Metabolic Regulation, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Overweight and Obese Adults" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412054

APA StylePrasertsri, P., Padkao, T., Boonla, O., Buddhisa, S., Prakobkaew, N., Sripinyowanich, S., & Phoemsapthawee, J. (2025). Synergistic Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training and Asparagus officinalis L. Root Extract Supplementation on Metabolic Regulation, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation in Overweight and Obese Adults. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12054. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412054