Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and FGF21 Dysregulation in Seipin-Deficient and BSCL2-Associated Celia’s Encephalopathy Murine Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

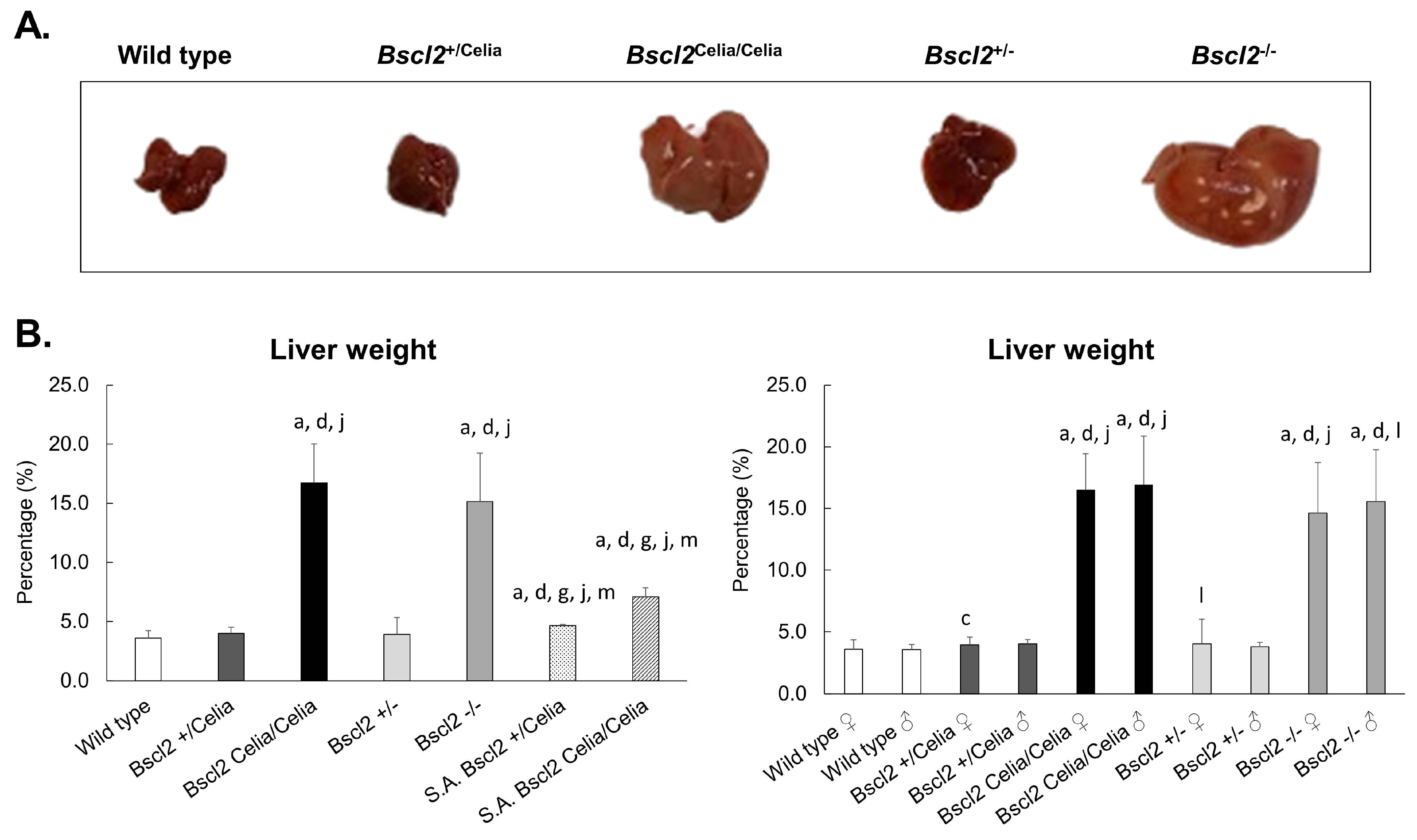

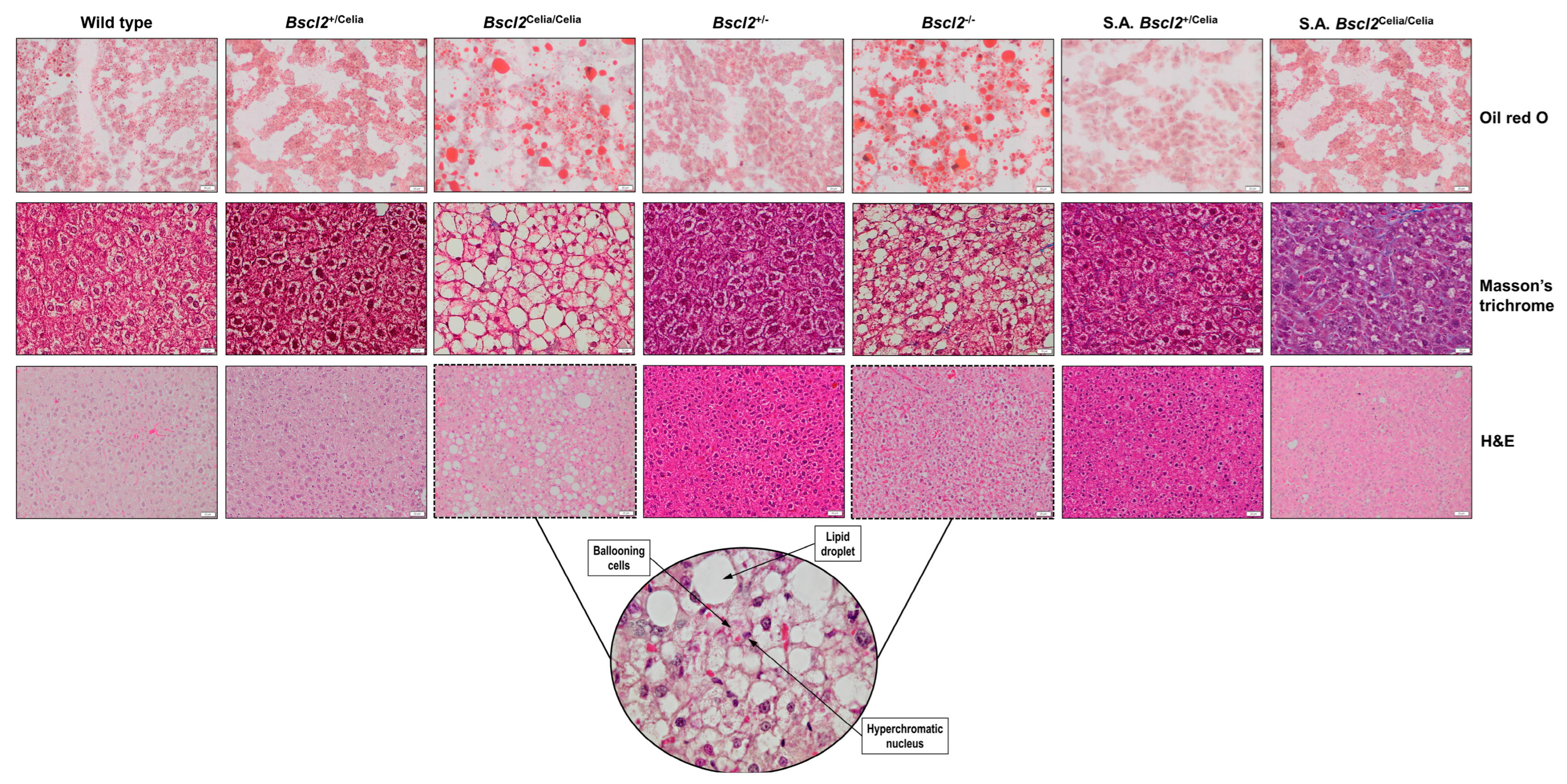

2.1. Macroscropic Examination of the Liver

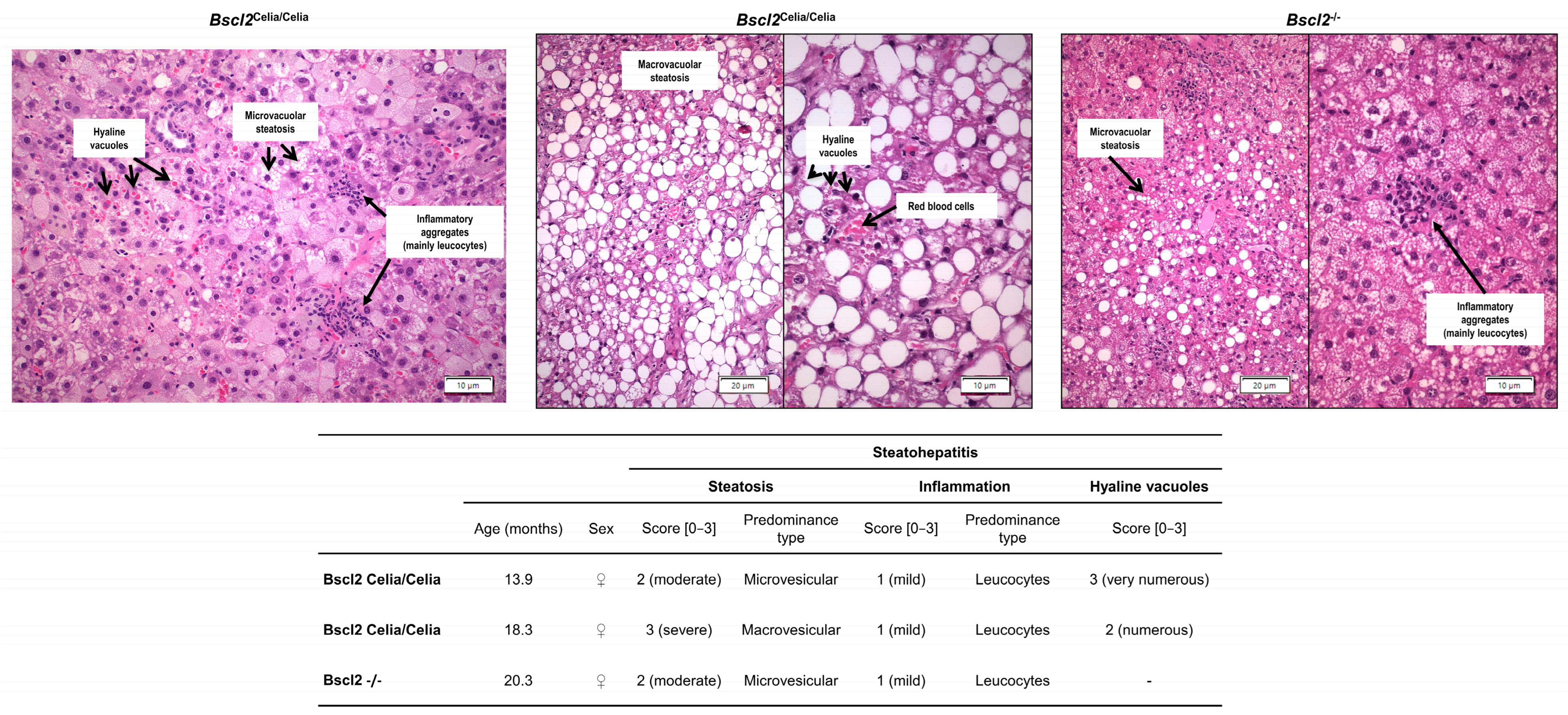

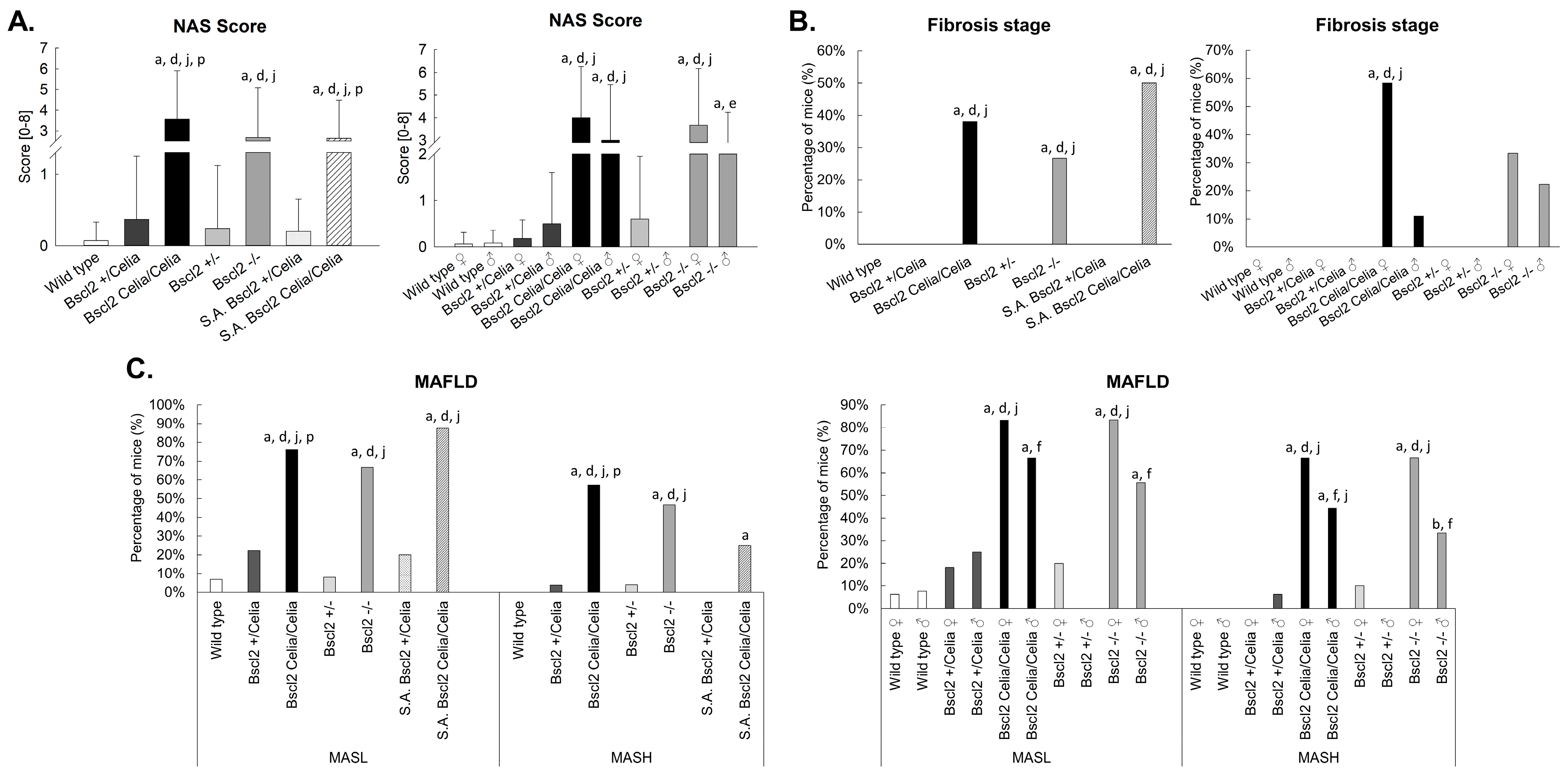

2.2. Histopathological Description of the Liver

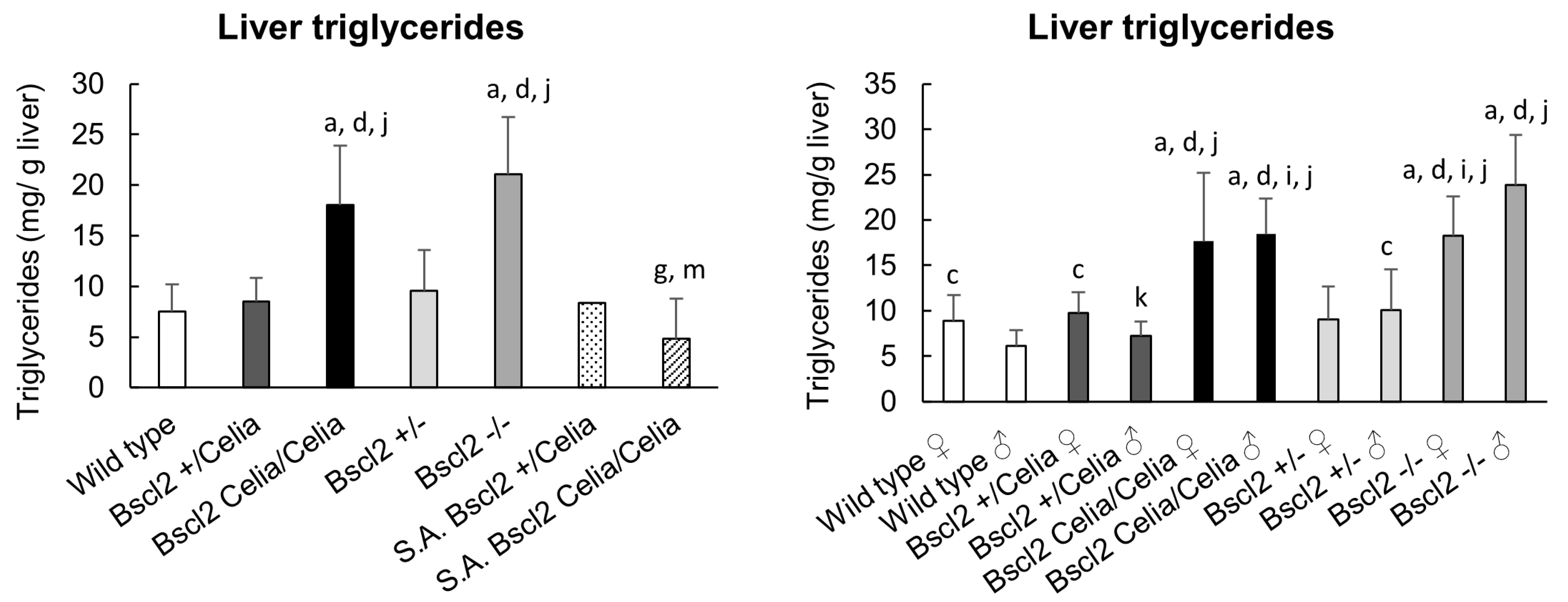

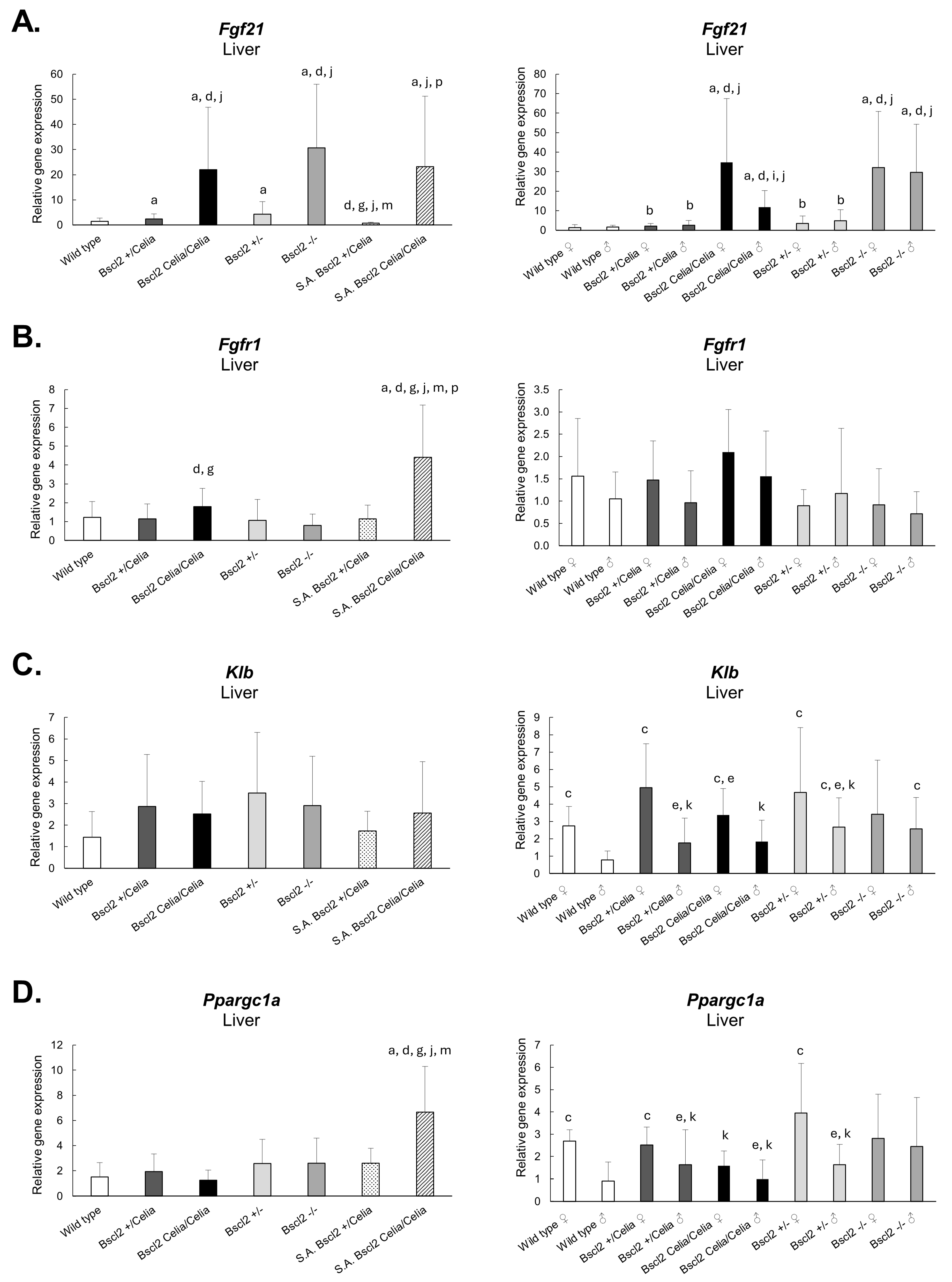

2.3. Gene Expression in Hepatic Tissue

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Experimental Design

4.1.1. Generation of Bscl2Celia/Celia and Bscl2−/− Mice

4.1.2. Maintenance and Care of Animals

4.1.3. Genotyping Protocol

4.2. Histology

4.2.1. Tissue Processing

4.2.2. Imaging

4.3. Total Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Activity Score

4.4. Triglyceride’s Analysis

4.5. RNA Isolation

4.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CGL2 | Congenital generalized lipodystrophy type 2 |

| FFA | Free fatty acids |

| IHBs | Intracytoplasmic hyaline bodies |

| MASL | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| NAFL | Non-alcoholic fatty liver |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NAS | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease activity score |

| NASH | Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis |

| PELD | Progressive encephalopathy with or without lipodystrophy |

| RT | Room temperature |

| S.A. | Severely affected |

| SKO | Seipin knock-out mice |

References

- Araujo-Vilar, D.; Santini, F. Diagnosis and treatment of lipodystrophy: A step-by-step approach. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2019, 42, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen-Navarro, E.; Sanchez-Iglesias, S.; Domingo-Jimenez, R.; Victoria, B.; Ruiz-Riquelme, A.; Rabano, A.; Loidi, L.; Beiras, A.; Gonzalez-Mendez, B.; Ramos, A.; et al. A new seipin-associated neurodegenerative syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2013, 50, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javor, E.D.; Ghany, M.G.; Cochran, E.K.; Oral, E.A.; DePaoli, A.M.; Premkumar, A.; Kleiner, D.E.; Gorden, P. Leptin reverses nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with severe lipodystrophy. Hepatology 2005, 41, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Brandao, J.R.; Cleto, E.; Santos, M.; Borges, T.; Santos Silva, E. Fatty Liver and Autoimmune Hepatitis: Two Forms of Liver Involvement in Lipodystrophies. GE Port. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 26, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo-Vilar, D.; Iglesias, S.S.; Guillín-Amarelle, C.; Fernández-Pombo, A.; de Tudela Cánovas, N.E.P.; Tudela, J.C. Guía Práctica Para el Diagnóstico y Tratamiento de las Lipodistrofias Infrecuentes; AELIP: Totana, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1542–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safar Zadeh, E.; Lungu, A.O.; Cochran, E.K.; Brown, R.J.; Ghany, M.G.; Heller, T.; Kleiner, D.E.; Gorden, P. The liver diseases of lipodystrophy: The long-term effect of leptin treatment. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollet, L.; Magre, J.; Cariou, B.; Prieur, X. Function of seipin: New insights from Bscl2/seipin knockout mouse models. Biochimie 2014, 96, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlroy, G.D.; Suchacki, K.; Roelofs, A.J.; Yang, W.; Fu, Y.; Bai, B.; Wallace, R.J.; De Bari, C.; Cawthorn, W.P.; Han, W.; et al. Adipose specific disruption of seipin causes early-onset generalised lipodystrophy and altered fuel utilisation without severe metabolic disease. Mol. Metab. 2018, 10, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieur, X.; Dollet, L.; Takahashi, M.; Nemani, M.; Pillot, B.; Le May, C.; Mounier, C.; Takigawa-Imamura, H.; Zelenika, D.; Matsuda, F.; et al. Thiazolidinediones partially reverse the metabolic disturbances observed in Bscl2/seipin-deficient mice. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 1813–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Zhou, H.; Saha, P.; Li, L.; Chan, L. Molecular mechanisms underlying fasting modulated liver insulin sensitivity and metabolism in male lipodystrophic Bscl2/Seipin-deficient mice. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 4215–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lounis, M.A.; Lalonde, S.; Rial, S.A.; Bergeron, K.F.; Ralston, J.C.; Mutch, D.M.; Mounier, C. Hepatic BSCL2 (Seipin) Deficiency Disrupts Lipid Droplet Homeostasis and Increases Lipid Metabolism via SCD1 Activity. Lipids 2017, 52, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Thein, S.; Guo, X.; Xu, F.; Venkatesh, B.; Sugii, S.; Radda, G.K.; Han, W. Seipin differentially regulates lipogenesis and adipogenesis through a conserved core sequence and an evolutionarily acquired C-terminus. Biochem. J. 2013, 452, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Wang, Q.A.; Tao, C.; Vishvanath, L.; Shao, M.; McDonald, J.G.; Gupta, R.K.; Scherer, P.E. Impact of tamoxifen on adipocyte lineage tracing: Inducer of adipogenesis and prolonged nuclear translocation of Cre recombinase. Mol. Metab. 2015, 4, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Wang, M.; Guo, X.; Qiu, X.; Liu, L.; Liao, J.; Liu, J.; Lu, G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G. Expression of seipin in adipose tissue rescues lipodystrophy, hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in seipin null mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 460, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlroy, G.D.; Mitchell, S.E.; Han, W.; Delibegovic, M.; Rochford, J.J. Ablation of Bscl2/seipin in hepatocytes does not cause metabolic dysfunction in congenital generalised lipodystrophy. Dis. Model. Mech. 2020, 13, dmm042655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miehle, K.; Ebert, T.; Kralisch, S.; Hoffmann, A.; Kratzsch, J.; Schlogl, H.; Stumvoll, M.; Fasshauer, M. Serum concentrations of fibroblast growth factor 21 are elevated in patients with congenital or acquired lipodystrophy. Cytokine 2016, 83, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollet, L.; Levrel, C.; Coskun, T.; Le Lay, S.; Le May, C.; Ayer, A.; Venara, Q.; Adams, A.C.; Gimeno, R.E.; Magre, J.; et al. FGF21 Improves the Adipocyte Dysfunction Related to Seipin Deficiency. Diabetes 2016, 65, 3410–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Softic, S.; Boucher, J.; Solheim, M.H.; Fujisaka, S.; Haering, M.F.; Homan, E.P.; Winnay, J.; Perez-Atayde, A.R.; Kahn, C.R. Lipodystrophy Due to Adipose Tissue-Specific Insulin Receptor Knockout Results in Progressive NAFLD. Diabetes 2016, 65, 2187–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobelo-Gomez, S.; Sanchez-Iglesias, S.; Rabano, A.; Senra, A.; Aguiar, P.; Gomez-Lado, N.; Garcia-Varela, L.; Burgueno-Garcia, I.; Lampon-Fernandez, L.; Fernandez-Pombo, A.; et al. A murine model of BSCL2-associated Celia’s encephalopathy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 187, 106300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo, M.M.; Estefania, C.V. Congenital Generalized Lipodystrophy Type 2 in a Patient from a High-Prevalence Area. J. Endocr. Soc. 2017, 1, 1012–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, H.; Kayoumu, A.; Wang, M.; Huang, W.; Liu, G. Diet rich in Docosahexaenoic Acid/Eicosapentaenoic Acid robustly ameliorates hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in seipin deficient lipodystrophy mice. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Deng, J.; Xu, G.; Peng, X.; Ju, S.; Liu, G.; et al. Seipin ablation in mice results in severe generalized lipodystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 3022–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, R.C.; Lam, S.M.; Shui, G.; Zhou, L.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; et al. Adipose-specific knockout of SEIPIN/BSCL2 results in progressive lipodystrophy. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2320–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.; Liu, X.; Gao, M.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Huang, W.; Liu, G. Dyslipidemia, steatohepatitis and atherogenesis in lipodystrophic apoE deficient mice with Seipin deletion. Gene 2018, 648, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Chang, B.; Saha, P.; Hartig, S.M.; Li, L.; Reddy, V.T.; Yang, Y.; Yechoor, V.; Mancini, M.A.; Chan, L. Berardinelli-seip congenital lipodystrophy 2/seipin is a cell-autonomous regulator of lipolysis essential for adipocyte differentiation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 32, 1099–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Bi, J.; Shui, G.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wenk, M.R.; Yang, H.; Huang, X. Tissue-autonomous function of Drosophila seipin in preventing ectopic lipid droplet formation. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1001364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomou, T.; Mori, M.A.; Dreyfuss, J.M.; Konishi, M.; Sakaguchi, M.; Wolfrum, C.; Rao, T.N.; Winnay, J.N.; Garcia-Martin, R.; Grinspoon, S.K.; et al. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature 2017, 542, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Lei, X.; Benson, T.; Mintz, J.; Xu, X.; Harris, R.B.; Weintraub, N.L.; Wang, X.; Chen, W. Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy 2 regulates adipocyte lipolysis, browning, and energy balance in adult animals. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 1912–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moure, R.; Cairo, M.; Moron-Ros, S.; Quesada-Lopez, T.; Campderros, L.; Cereijo, R.; Hernaez, A.; Villarroya, F.; Giralt, M. Levels of beta-klotho determine the thermogenic responsiveness of adipose tissues: Involvement of the autocrine action of FGF21. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 320, E822–E834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A.C.; Cheng, C.C.; Coskun, T.; Kharitonenkov, A. FGF21 requires betaklotho to act in vivo. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Boney-Montoya, J.; Owen, B.M.; Bookout, A.L.; Coate, K.C.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Kliewer, S.A. betaKlotho is required for fibroblast growth factor 21 effects on growth and metabolism. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharitonenkov, A.; Dunbar, J.D.; Bina, H.A.; Bright, S.; Moyers, J.S.; Zhang, C.; Ding, L.; Micanovic, R.; Mehrbod, S.F.; Knierman, M.D.; et al. FGF-21/FGF-21 receptor interaction and activation is determined by betaKlotho. J. Cell Physiol. 2008, 215, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.C.; Puigserver, P.; Chen, G.; Donovan, J.; Wu, Z.; Rhee, J.; Adelmant, G.; Stafford, J.; Kahn, C.R.; Granner, D.K.; et al. Control of hepatic gluconeogenesis through the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1. Nature 2001, 413, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finck, B.N.; Gropler, M.C.; Chen, Z.; Leone, T.C.; Croce, M.A.; Harris, T.E.; Lawrence, J.C., Jr.; Kelly, D.P. Lipin 1 is an inducible amplifier of the hepatic PGC-1alpha/PPARalpha regulatory pathway. Cell Metab. 2006, 4, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; He, J.; Li, S.; Song, L.; Guo, X.; Yao, W.; Zou, D.; Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Bai, F.; et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) inhibits macrophage-mediated inflammation by activating Nrf2 and suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2016, 38, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.M.; Meers, G.M.; Booth, F.W.; Fritsche, K.L.; Hardin, C.D.; Thyfault, J.P.; Ibdah, J.A. PGC-1alpha overexpression results in increased hepatic fatty acid oxidation with reduced triacylglycerol accumulation and secretion. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, G979–G992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.F.; Ku, H.C.; Lin, H. PGC-1alpha as a Pivotal Factor in Lipid and Metabolic Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xu, P.F.; Li, J.Y.; Liu, X.J.; Wu, X.Y.; Xu, F.; Xie, B.C.; Huang, X.M.; Zhou, Z.H.; Kayoumu, A.; et al. Adipose tissue transplantation ameliorates lipodystrophy-associated metabolic disorders in seipin-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 316, E54–E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Peng, L.; Xia, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, W.; Liu, T.; Jia, D. Role of Seipin in Human Diseases and Experimental Animal Models. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Wang, H.; Pan, X.; Little, P.J.; Xu, S.; Weng, J. Mouse models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): Pathomechanisms and pharmacotherapies. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5681–5697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herck, M.A.; Vonghia, L.; Francque, S.M. Animal Models of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease-A Starter’s Guide. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, N.; Kado, S.; Kano, M.; Masuoka, N.; Nagata, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Miyazaki, K.; Ishikawa, F. A high-fat diet and multiple administration of carbon tetrachloride induces liver injury and pathological features associated with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2013, 40, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniciu, D.C.; Hashiguchi, T.; Shibazaki, Y.; Bisgaier, C.L. Gemcabene downregulates inflammatory, lipid-altering and cell-signaling genes in the STAM model of NASH. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Shin, J.W.; Park, S.K.; Seo, J.N.; Li, L.; Jang, J.J.; Lee, M.J. Diethylnitrosamine (DEN) induces irreversible hepatocellular carcinogenesis through overexpression of G1/S-phase regulatory proteins in rat. Toxicol. Lett. 2009, 191, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang-Doran, I.; Sleigh, A.; Rochford, J.J.; O’Rahilly, S.; Savage, D.B. Lipodystrophy: Metabolic insights from a rare disorder. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 207, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raygada, M.; Rennert, O. Congenital generalized lipodystrophy: Profile of the disease and gender differences in two siblings. Clin. Genet. 2005, 67, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A. Gender differences in the prevalence of metabolic complications in familial partial lipodystrophy (Dunnigan variety). J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 1776–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlroy, G.D.; Mitchell, S.E.; Han, W.; Delibegovic, M.; Rochford, J.J. Female adipose tissue-specific Bscl2 knockout mice develop only moderate metabolic dysfunction when housed at thermoneutrality and fed a high-fat diet. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. BMJ Open Sci. 2020, 4, e100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudamore, C.L. A Practical Guide to the Histology of the Mouse; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; Ferrell, L.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Torbenson, M.S.; Unalp-Arida, A.; et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane Stanley, G.H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Iglesias, S.; Fernandez-Liste, A.; Guillin-Amarelle, C.; Rabano, A.; Rodriguez-Canete, L.; Gonzalez-Mendez, B.; Fernandez-Pombo, A.; Senra, A.; Araujo-Vilar, D. Does Seipin Play a Role in Oxidative Stress Protection and Peroxisome Biogenesis? New Insights from Human Brain Autopsies. Neuroscience 2018, 396, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victoria, B.; Cabezas-Agricola, J.M.; Gonzalez-Mendez, B.; Lattanzi, G.; Del Coco, R.; Loidi, L.; Barreiro, F.; Calvo, C.; Lado-Abeal, J.; Araujo-Vilar, D. Reduced adipogenic gene expression in fibroblasts from a patient with type 2 congenital generalized lipodystrophy. Diabet. Med. 2010, 27, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5′-3′) | Probe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Symbol | Forward | Reverse | Sequence (5′-3′) |

| 18S ribosomal RNA | Rn18s | AAACGGCTACCACATCCAAG | TACAGGGCCTCGAAAGAGTC | CGCAAATTACCCACTCCCGACCCG |

| Fibroblast growth factor 21 | Fgf21 | AGCATACCCCATCCCTGACT | GTACCTCTGCCGGACTTGAC | CTCCTCCA |

| Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 | Fgfr1 | ATTGGAGGCTACAAGGTTCG | GAAGGCACCACAGAATCCAT | CCTGGAGC |

| Klotho beta | Klb | CGAGCCCATTGTTACCTTGT | TTTTCCAGCCCCCATATTC | CCTGGAGC |

| Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor, gamma, coactivator 1 alpha | Ppargc1a | GAGAAGCTTGCGCAGGTAAC | TCCCATGAGGTATTGACCATC | TCCTCAGC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cobelo-Gómez, S.; García-Formoso, L.; Fernández-Pombo, A.; Lázare-Iglesias, H.; Díaz-López, E.; Prado-Moraña, T.; Rodríguez-Sobrino, L.; Senra, A.; Araújo-Vilar, D.; Sánchez-Iglesias, S. Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and FGF21 Dysregulation in Seipin-Deficient and BSCL2-Associated Celia’s Encephalopathy Murine Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12037. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412037

Cobelo-Gómez S, García-Formoso L, Fernández-Pombo A, Lázare-Iglesias H, Díaz-López E, Prado-Moraña T, Rodríguez-Sobrino L, Senra A, Araújo-Vilar D, Sánchez-Iglesias S. Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and FGF21 Dysregulation in Seipin-Deficient and BSCL2-Associated Celia’s Encephalopathy Murine Models. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12037. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412037

Chicago/Turabian StyleCobelo-Gómez, Silvia, Lía García-Formoso, Antía Fernández-Pombo, Héctor Lázare-Iglesias, Everardo Díaz-López, Teresa Prado-Moraña, Laura Rodríguez-Sobrino, Ana Senra, David Araújo-Vilar, and Sofía Sánchez-Iglesias. 2025. "Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and FGF21 Dysregulation in Seipin-Deficient and BSCL2-Associated Celia’s Encephalopathy Murine Models" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12037. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412037

APA StyleCobelo-Gómez, S., García-Formoso, L., Fernández-Pombo, A., Lázare-Iglesias, H., Díaz-López, E., Prado-Moraña, T., Rodríguez-Sobrino, L., Senra, A., Araújo-Vilar, D., & Sánchez-Iglesias, S. (2025). Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and FGF21 Dysregulation in Seipin-Deficient and BSCL2-Associated Celia’s Encephalopathy Murine Models. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12037. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412037