Hyperglycemia Induced in Sprague–Dawley Rats Modulates the Expression of CD36 and CD69 During Wound Healing

Abstract

1. Introduction

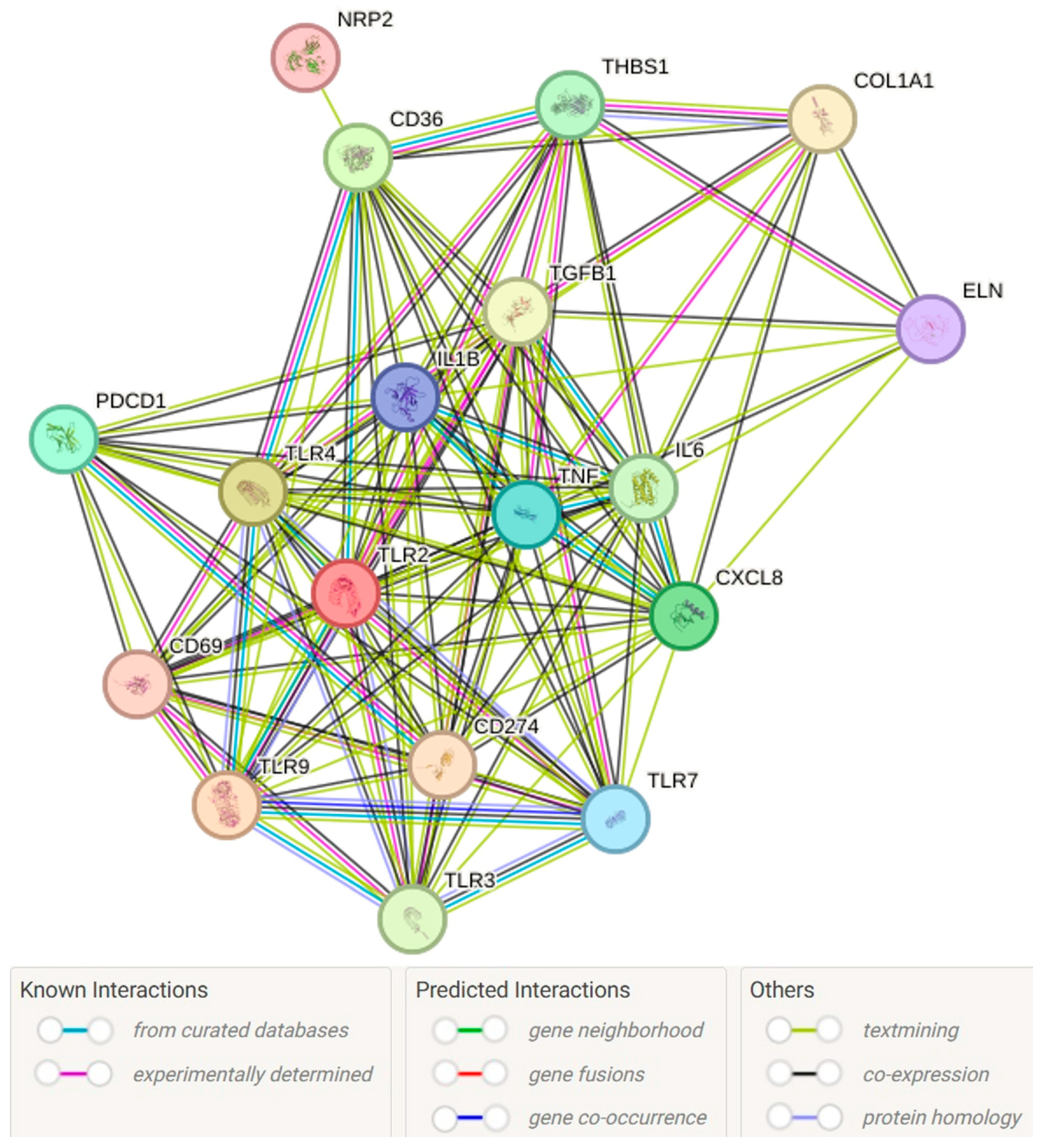

2. Results

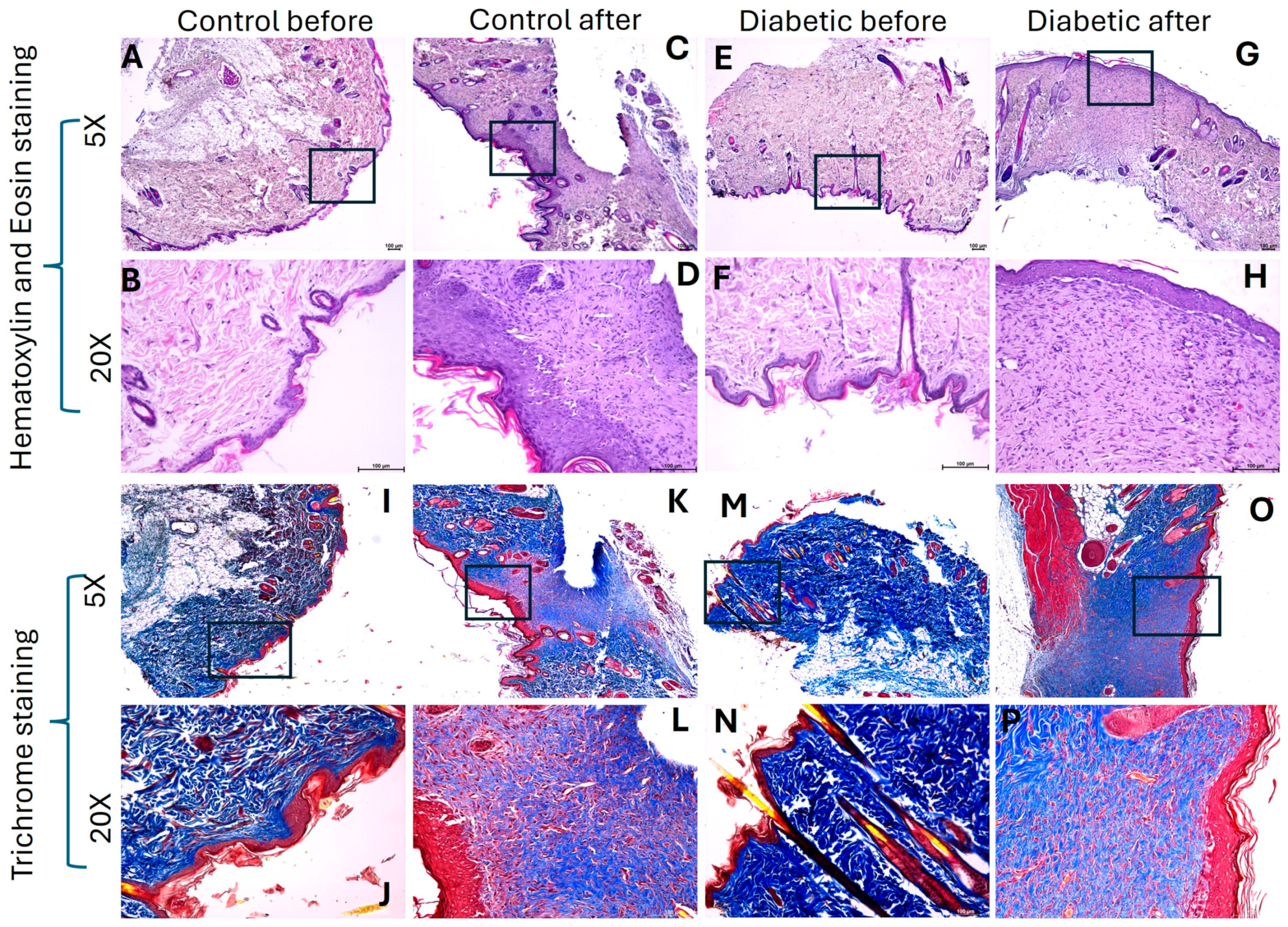

2.1. Hyperglycemia Decreases Collagen Content in Healed Tissues

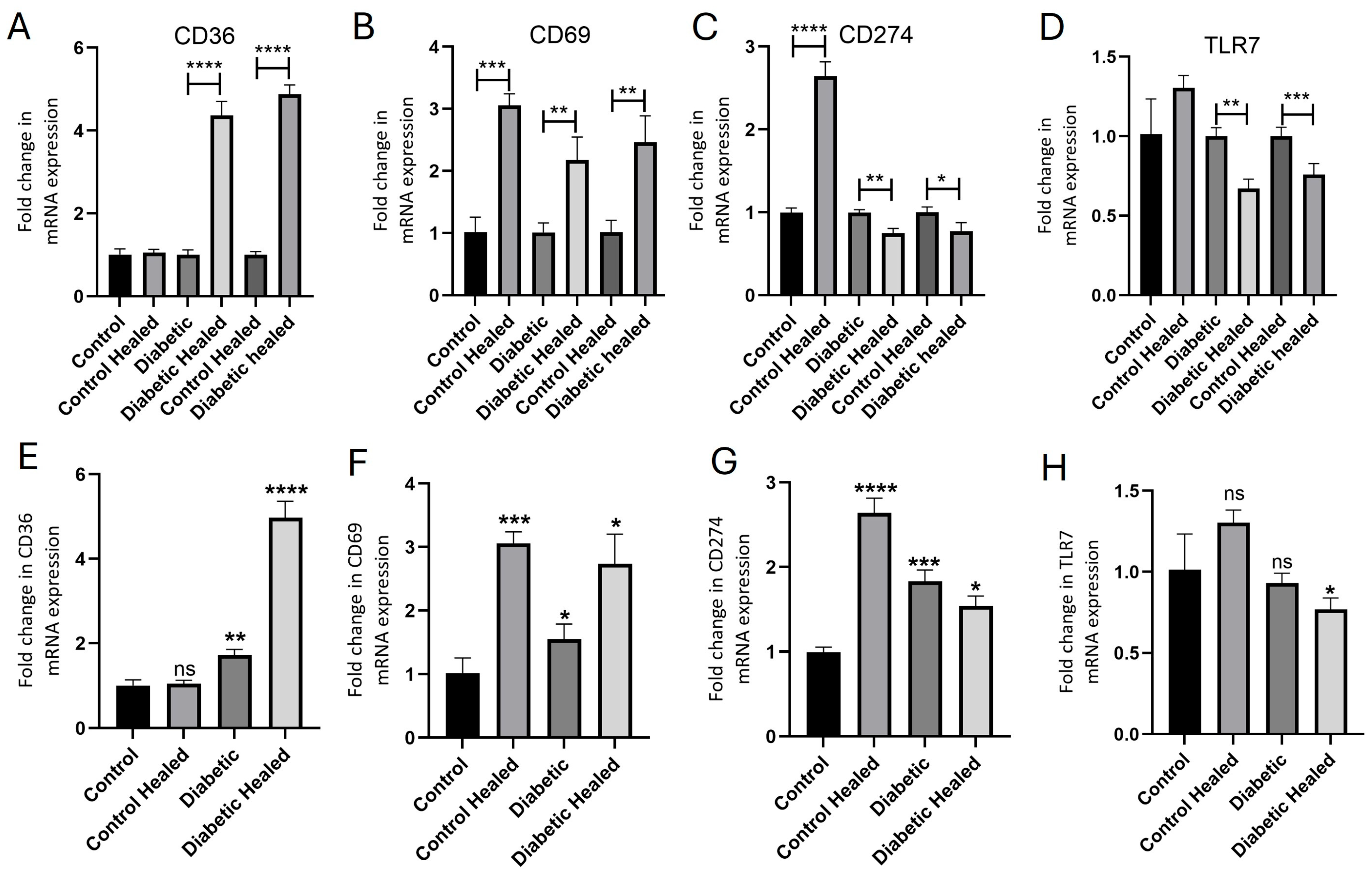

2.2. Hyperglycemia Modulates the Gene Expression of CD36, CD69, CD274, and TLR-7 in Healed Tissues

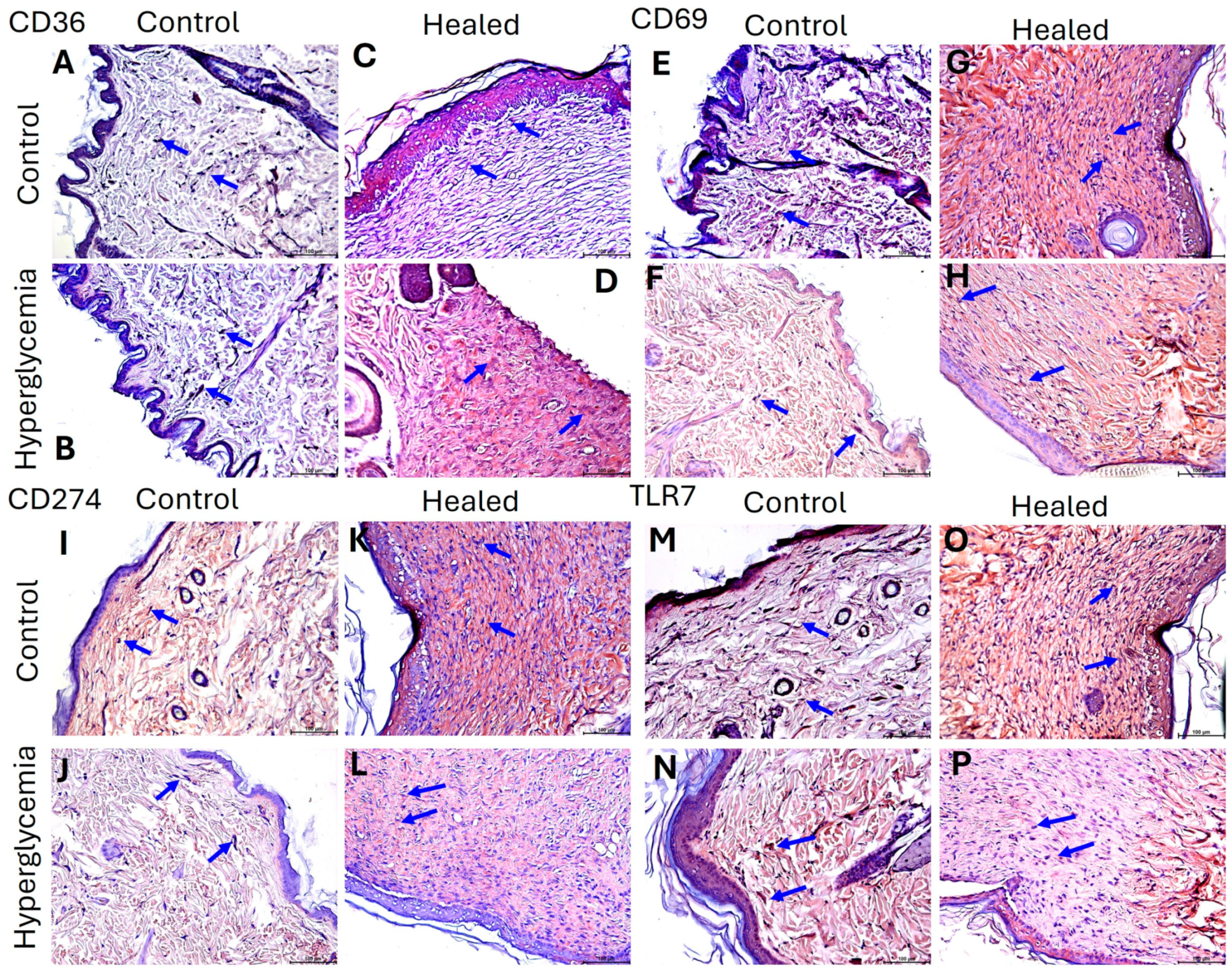

2.3. Hyperglycemia Modulate the Protein Expression of CD36, CD69, CD274, and TLR-7 in Healed Tissues

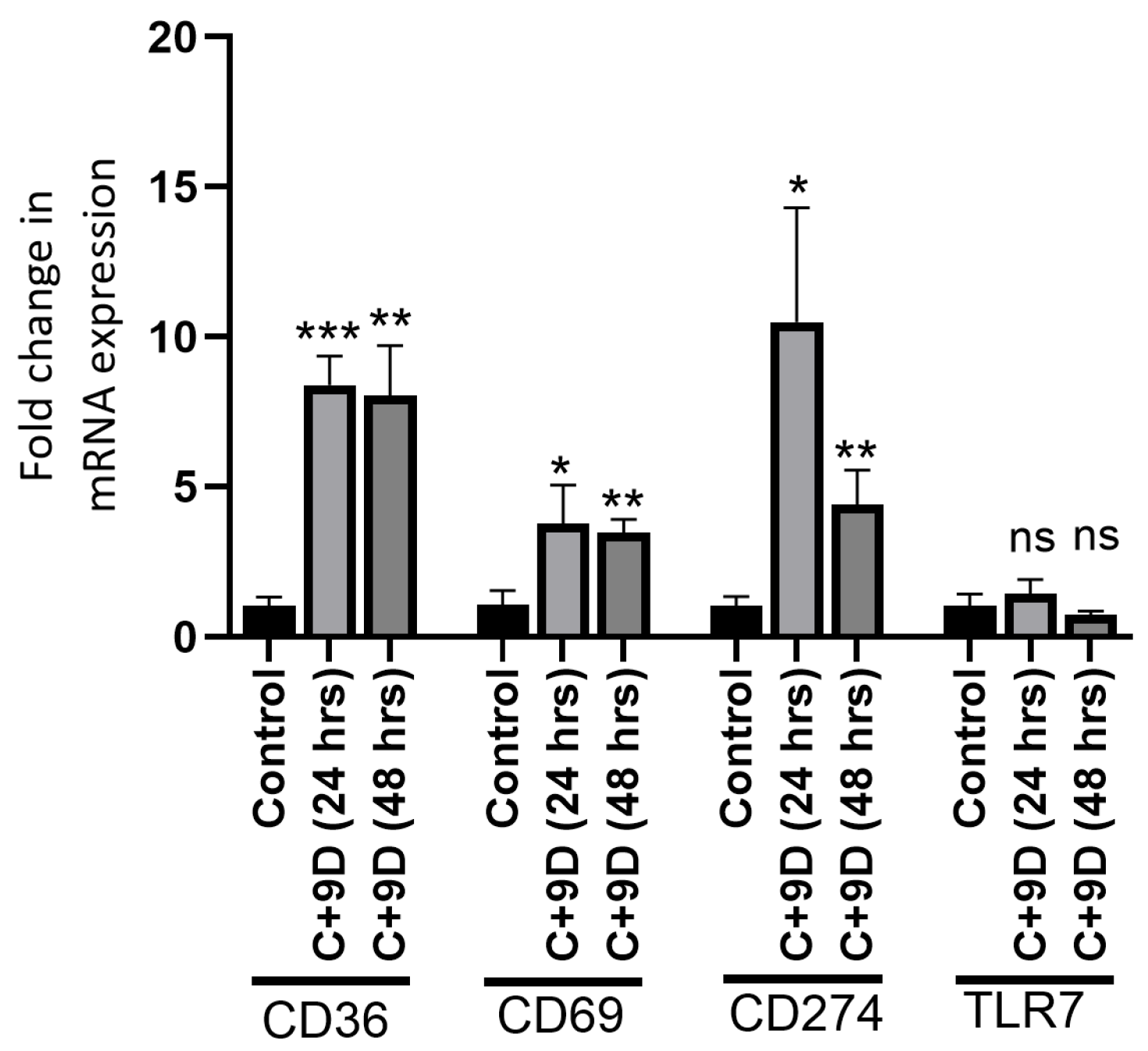

2.4. Hyperglycemia Modulate the Protein Expression of CD36, CD69, CD274, and TLR-7 in Fibroblasts

2.5. Hyperglycemia Modulates the Gene Expression of CD36, CD69, and CD274 in Rat Fibroblasts

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Model

4.2. Tissue Processing

4.3. Histology

4.4. Immunohistochemistry

4.5. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

4.6. Cell Culture and In Vitro Studies

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end-products |

| DFUs | Diabetic foot ulcers |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| IL | Interleukin |

| MMPs | Matrix metalloproteinases |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa beta |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TLR-7 | Toll-like receptor-7 |

| TSP1 | Thrombospondin 1 |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor beta |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Fonseca, V.A. Defining and characterizing the progression of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009, 32 (Suppl. S2), S151–S156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, J.; Kojima, H.; Katagi, M.; Nakagawa, T.; Nakae, Y.; Terashima, T.; Kurakane, T.; Kubota, M.; Maegawa, H.; Udagawa, J. Hyperglycemia Induces Skin Barrier Dysfunctions with Impairment of Epidermal Integrity in Non-Wounded Skin of Type 1 Diabetic Mice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.; Moellmer, R.; Agrawal, D.K. The role of CXCL8 in chronic nonhealing diabetic foot ulcers and phenotypic changes in fibroblasts: A molecular perspective. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 1565–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccioli, L.; Izzo, V.; Meloni, M.; Vainieri, E.; Ruotolo, V.; Giurato, L. Non-healing foot ulcers in diabetic patients: General and local interfering conditions and management options with advanced wound dressings. J. Wound Care 2015, 24, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theocharidis, G.; Baltzis, D.; Roustit, M.; Tellechea, A.; Dangwal, S.; Khetani, R.S.; Shu, B.; Zhao, W.; Fu, J.; Bhasin, S.; et al. Integrated Skin Transcriptomics and Serum Multiplex Assays Reveal Novel Mechanisms of Wound Healing in Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes 2020, 69, 2157–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, G.; Lu, Z. Extensive serum biomarker analysis before and after treatment in healing of diabetic foot ulcers using a cytokine antibody array. Cytokine 2020, 133, 155173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shofler, D.; Rai, V.; Mansager, S.; Cramer, K.; Agrawal, D.K. Impact of resolvin mediators in the immunopathology of diabetes and wound healing. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 17, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.L.; Febbraio, M. CD36, a scavenger receptor involved in immunity, metabolism, angiogenesis, and behavior. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2, re3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.; Peng, Y.; Hang, W.; Nie, J.; Zhou, N.; Wang, D.W. The role of CD36 in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.W.; Zuppe, H.T.; Kurokawa, M. The Role of CD36 in Cancer Progression and Its Value as a Therapeutic Target. Cells 2023, 12, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifarelli, V.; Ivanov, S.; Xie, Y.; Son, N.H.; Saunders, B.T.; Pietka, T.A.; Shew, T.M.; Yoshino, J.; Sundaresan, S.; Davidson, N.O.; et al. CD36 deficiency impairs the small intestinal barrier and induces subclinical inflammation in mice. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 2017, 3, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLeon-Pennell, K.Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, B.; Cates, C.A.; Iyer, R.P.; Cannon, P.; Shah, P.; Aiyetan, P.; Halade, G.V.; Ma, Y.; et al. CD36 Is a Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Substrate That Stimulates Neutrophil Apoptosis and Removal During Cardiac Remodeling. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2016, 9, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Fernandez, M.; de la Fuente, H.; Martin, P.; Cibrian, D.; Sanchez-Madrid, F. Unraveling CD69 signaling pathways, ligands and laterally associated molecules. EXCLI J. 2023, 22, 334–351. [Google Scholar]

- Cibrian, D.; Sanchez-Madrid, F. CD69: From activation marker to metabolic gatekeeper. Eur. J. Immunol. 2017, 47, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, Y.; Yang, P.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Jin, Z.; Xu, L. CD69 is a Promising Immunotherapy and Prognosis Prediction Target in Cancer. Immunotargets Ther. 2024, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liappas, G.; Gonzalez-Mateo, G.T.; Sanchez-Diaz, R.; Lazcano, J.J.; Lasarte, S.; Matesanz-Marin, A.; Zur, R.; Ferrantelli, E.; Ramirez, L.G.; Aguilera, A.; et al. Immune-Regulatory Molecule CD69 Controls Peritoneal Fibrosis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 3561–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Yang, F.; Zhang, F.; Guo, D.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Liang, T.; Wang, J.; Cai, Z.; Jin, H. CD69 enhances immunosuppressive function of regulatory T-cells and attenuates colitis by prompting IL-10 production. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregorio, J.; Meller, S.; Conrad, C.; Di Nardo, A.; Homey, B.; Lauerma, A.; Arai, N.; Gallo, R.L.; Digiovanni, J.; Gilliet, M. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense skin injury and promote wound healing through type I interferons. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 2921–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Agrawal, N.K.; Gupta, S.K.; Mohan, G.; Chaturvedi, S.; Singh, K. Increased expression of endosomal members of toll-like receptor family abrogates wound healing in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int. Wound J. 2016, 13, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer-Geissler, J.C.J.; Schwingenschuh, S.; Zacharias, M.; Einsiedler, J.; Kainz, S.; Reisenegger, P.; Holecek, C.; Hofmann, E.; Wolff-Winiski, B.; Fahrngruber, H.; et al. The Impact of Prolonged Inflammation on Wound Healing. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinhal-Enfield, G.; Ramanathan, M.; Hasko, G.; Vogel, S.N.; Salzman, A.L.; Boons, G.J.; Leibovich, S.J. An angiogenic switch in macrophages involving synergy between Toll-like receptors 2, 4, 7, and 9 and adenosine A(2A) receptors. Am. J. Pathol. 2003, 163, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salagianni, M.; Galani, I.E.; Lundberg, A.M.; Davos, C.H.; Varela, A.; Gavriil, A.; Lyytikainen, L.P.; Lehtimaki, T.; Sigala, F.; Folkersen, L.; et al. Toll-like receptor 7 protects from atherosclerosis by constraining “inflammatory” macrophage activation. Circulation 2012, 126, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kleijn, D.P.V.; Chong, S.Y.; Wang, X.; Yatim, S.; Fairhurst, A.M.; Vernooij, F.; Zharkova, O.; Chan, M.Y.; Foo, R.S.Y.; Timmers, L.; et al. Toll-like receptor 7 deficiency promotes survival and reduces adverse left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1791–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Guo, W.; Qiu, W.; Ao, L.Q.; Yao, M.W.; Xing, W.; Yu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wu, X.F.; Li, Z.; et al. Fibroblast-like cells Promote Wound Healing via PD-L1-mediated Inflammation Resolution. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4388–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanheimer, R.G.; Umpierrez, G.E.; Stumpf, V. Decreased collagen production in diabetic rats. Diabetes 1988, 37, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, E.; Vibe-Petersen, J.; Jorgensen, L.N.; Madsen, S.M.; Agren, M.S.; Holstein, P.E.; Perrild, H.; Gottrup, F. Decrease of collagen deposition in wound repair in type 1 diabetes independent of glycemic control. Arch. Surg. 2003, 138, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.J.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Kou, X.X.; Zhang, J.N.; Gan, Y.H.; Zhou, Y.H.; Wang, X.D. Chronic inflammation deteriorates structure and function of collagen fibril in rat temporomandibular joint disc. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew-Steiner, S.S.; Roy, S.; Sen, C.K. Collagen in Wound Healing. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.S.; Karunakaran, U.; Suma, E.; Chung, S.M.; Won, K.C. The Role of CD36 in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Beta-Cell Dysfunction and Beyond. Diabetes Metab. J. 2020, 44, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Nag, S.; Mukherjee, O.; Das, N.; Banerjee, P.; Majumdar, T.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Maedler, K.; Kundu, R. CD36 inhibition corrects lipid-FetuinA mediated insulin secretory defects by preventing intracellular lipid accumulation and inflammation in the pancreatic beta cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2025, 1871, 167580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, B.W.; Black, L.L.; Zimmerman, K.A.; Metz, A.E.; Steele, C.; Murphy-Ullrich, J.E.; Kabarowski, J.H. CD36, but not G2A, modulates efferocytosis, inflammation, and fibrosis following bleomycin-induced lung injury. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.F.; Borrelli, M.R.; Garcia, J.T.; Januszyk, M.; King, M.; Lerbs, T.; Cui, L.; Moore, A.L.; Shen, A.H.; Mascharak, S.; et al. JUN promotes hypertrophic skin scarring via CD36 in preclinical in vitro and in vivo models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabb3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, E.; Re, A.; Hamel, N.; Fu, C.; Bush, H.; McCaffrey, T.; Asch, A.S. A link between diabetes and atherosclerosis: Glucose regulates expression of CD36 at the level of translation. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculite, C.M.; Enciu, A.M.; Hinescu, M.E. CD 36: Focus on Epigenetic and Post-Transcriptional Regulation. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Varghese, Z.; Moorhead, J.F.; Chen, Y.; Ruan, X.Z. CD36 and lipid metabolism in the evolution of atherosclerosis. Br. Med. Bull. 2018, 126, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Amaro, R.; Cortes, J.R.; Sanchez-Madrid, F.; Martin, P. Is CD69 an effective brake to control inflammatory diseases? Trends Mol. Med. 2013, 19, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Bolick, D.T.; Lukashev, D.; Lappas, C.; Sitkovsky, M.; Lynch, K.R.; Hedrick, C.C. Sphingosine-1-phosphate reduces CD4+ T-cell activation in type 1 diabetes through regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor short isoform I.1 and CD69. Diabetes 2008, 57, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, S.F.; Ramsdell, F.; Alderson, M.R. The activation antigen CD69. Stem. Cells 1994, 12, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, D.; Shen, F.; Xue, T.T.; Jiang, J.S.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Song, J.K.; Kuai, L.; Wang, M.X.; et al. Epidermal keratinocytes-specific PD-L1 knockout causes delayed healing of diabetic wounds. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 143, 113540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Chen, J.; Bai, J.; Zhang, H.; Tao, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, H.; Wu, H.; Shen, Q.; Yin, T. High glucose-upregulated PD-L1 expression through RAS signaling-driven downregulation of PTRH1 leads to suppression of T cell cytotoxic function in tumor environment. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Liu, X.; Liang, J.; Habiel, D.M.; Kulur, V.; Coelho, A.L.; Deng, N.; Xie, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; et al. PD-L1 on invasive fibroblasts drives fibrosis in a humanized model of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e125326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Pan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Dong, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Hyperglycemia induces an immunosuppressive microenvironment in colorectal cancer liver metastases by recruiting peripheral blood monocytes through the CCL3-CCR1 axis. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D.; Schutte, W.; Turzer, S.; Seliger, B.; Moller, M. High PD-L1/CD274 Expression of Monocytes and Blood Dendritic Cells Is a Risk Factor in Lung Cancer Patients Undergoing Treatment with PD1 Inhibitor Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasu, M.R.; Isseroff, R.R. Toll-like receptors in wound healing: Location, accessibility, and timing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 1955–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arpa, P.; Leung, K.P. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling in Burn Wound Healing and Scarring. Adv. Wound Care 2017, 6, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liotti, F.; Marotta, M.; Sorriento, D.; Pone, E.; Morra, F.; Melillo, R.M.; Prevete, N. Toll-Like Receptor 7 Mediates Inflammation Resolution and Inhibition of Angiogenesis in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasu, M.R.; Devaraj, S.; Zhao, L.; Hwang, D.H.; Jialal, I. High glucose induces toll-like receptor expression in human monocytes: Mechanism of activation. Diabetes 2008, 57, 3090–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| CD36 | Forward: GAAGCCAATCTTACGGTCCTG Reverse: CACATTTCAGAAGGCGGCAA |

| CD69 | Forward: TAGACTGCGAGGCAAACTTAC Reverse: GCTATGGCACAGTCACCTATAC |

| CD274 | Forward: TTACAGGTTGTCCCTGGTAATG Reverse: CCTCCAGGAAACAGTGTCTATG |

| TLR-7 | Forward: TCCTTGAGTGGCCTACAAATC Reverse: CTTCAGAGAGCTAGACTGTTTCC |

| 18S | Forward: GTAACCCGTTGAACCCCATT Reverse: CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ho, V.; Tran, T.; Patel, J.; Teshome, B.; Rai, V. Hyperglycemia Induced in Sprague–Dawley Rats Modulates the Expression of CD36 and CD69 During Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412032

Ho V, Tran T, Patel J, Teshome B, Rai V. Hyperglycemia Induced in Sprague–Dawley Rats Modulates the Expression of CD36 and CD69 During Wound Healing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412032

Chicago/Turabian StyleHo, Vy, Tommy Tran, Jaylan Patel, Betelhem Teshome, and Vikrant Rai. 2025. "Hyperglycemia Induced in Sprague–Dawley Rats Modulates the Expression of CD36 and CD69 During Wound Healing" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412032

APA StyleHo, V., Tran, T., Patel, J., Teshome, B., & Rai, V. (2025). Hyperglycemia Induced in Sprague–Dawley Rats Modulates the Expression of CD36 and CD69 During Wound Healing. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412032