Neuroplastic Effects Induced by Hypercapnic Hypoxia in Rat Focal Ischemic Stroke Are Driven via BDNF and VEGF Signaling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Motor Coordination and Neurological Deficit in Rats

2.2. Rotarod Test Results and Neurological Deficit Assessment

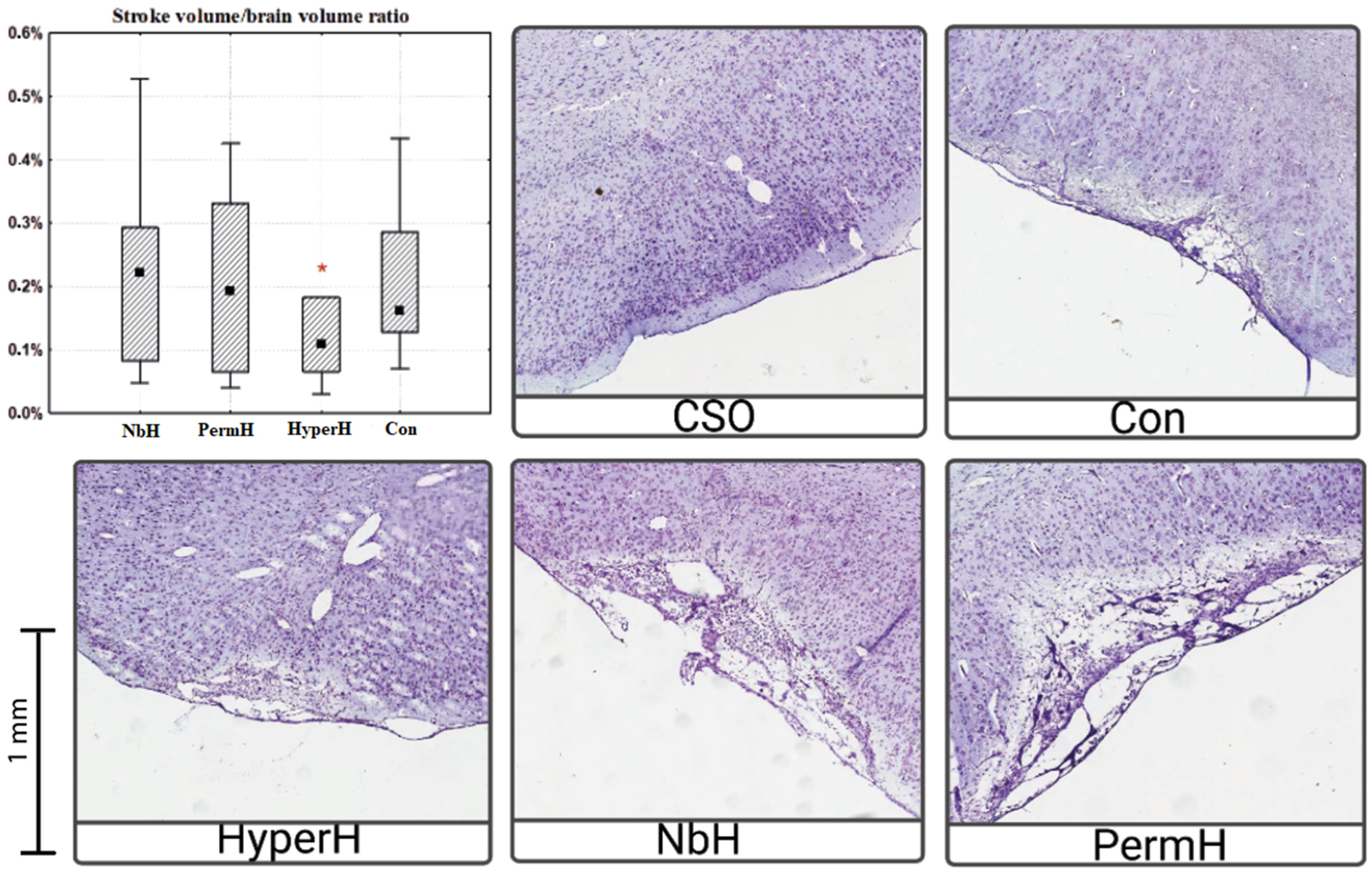

2.3. Infarct Volume in the Cerebral Cortex

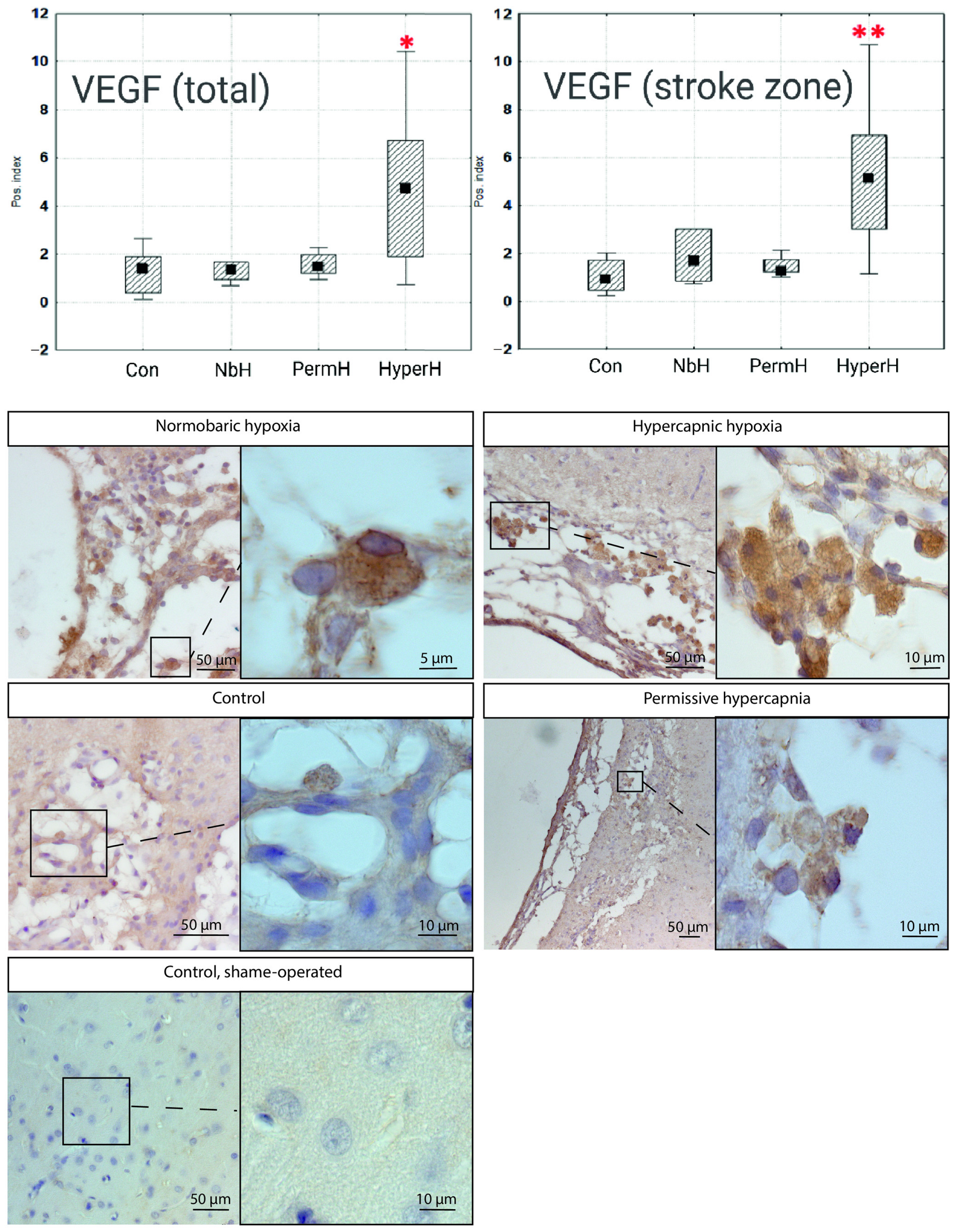

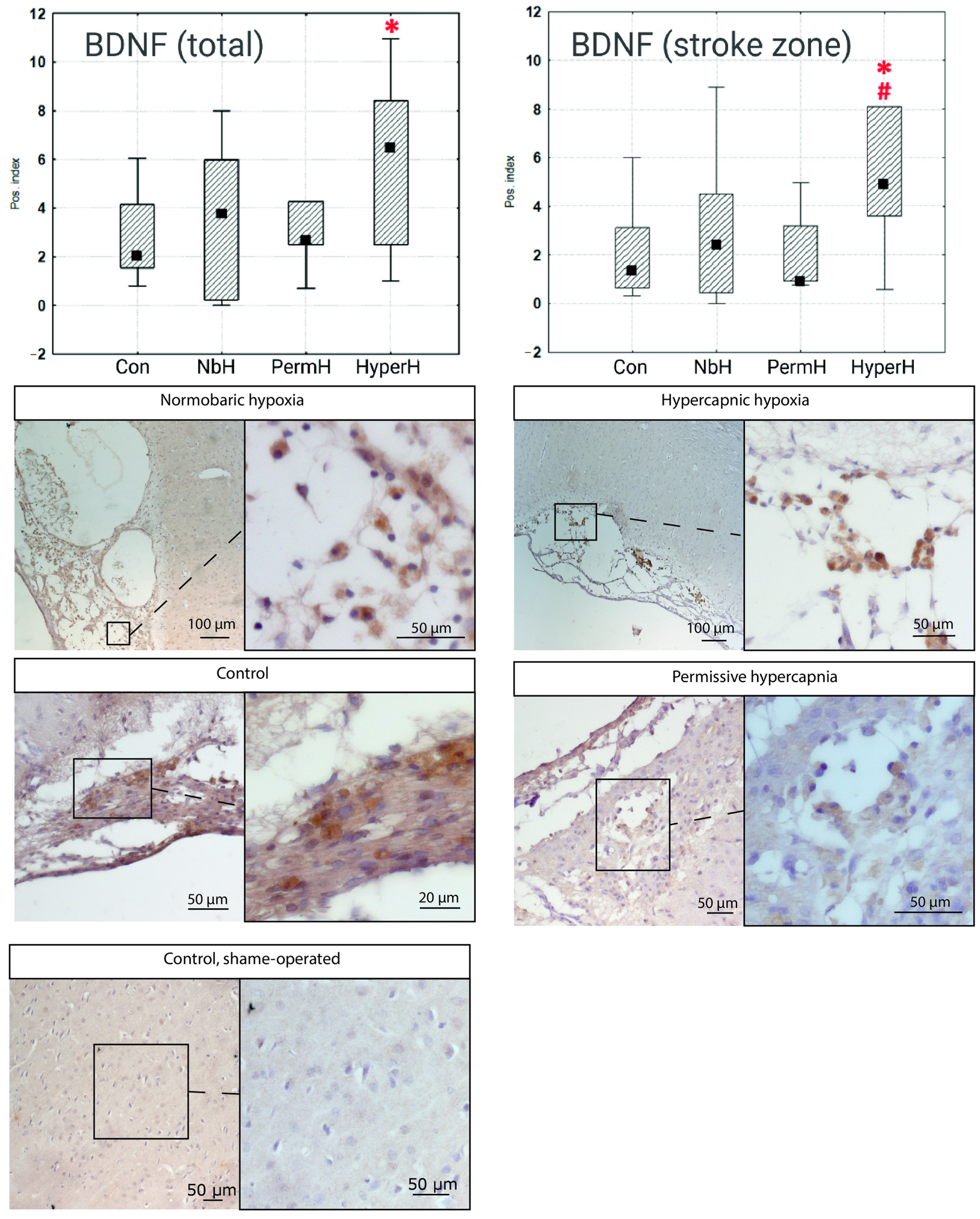

2.4. VEGF and BDNF Expression in Cells from the Ischemic Cortical Region

2.5. Serum Levels of S100 and NSE in Rats

3. Discussion

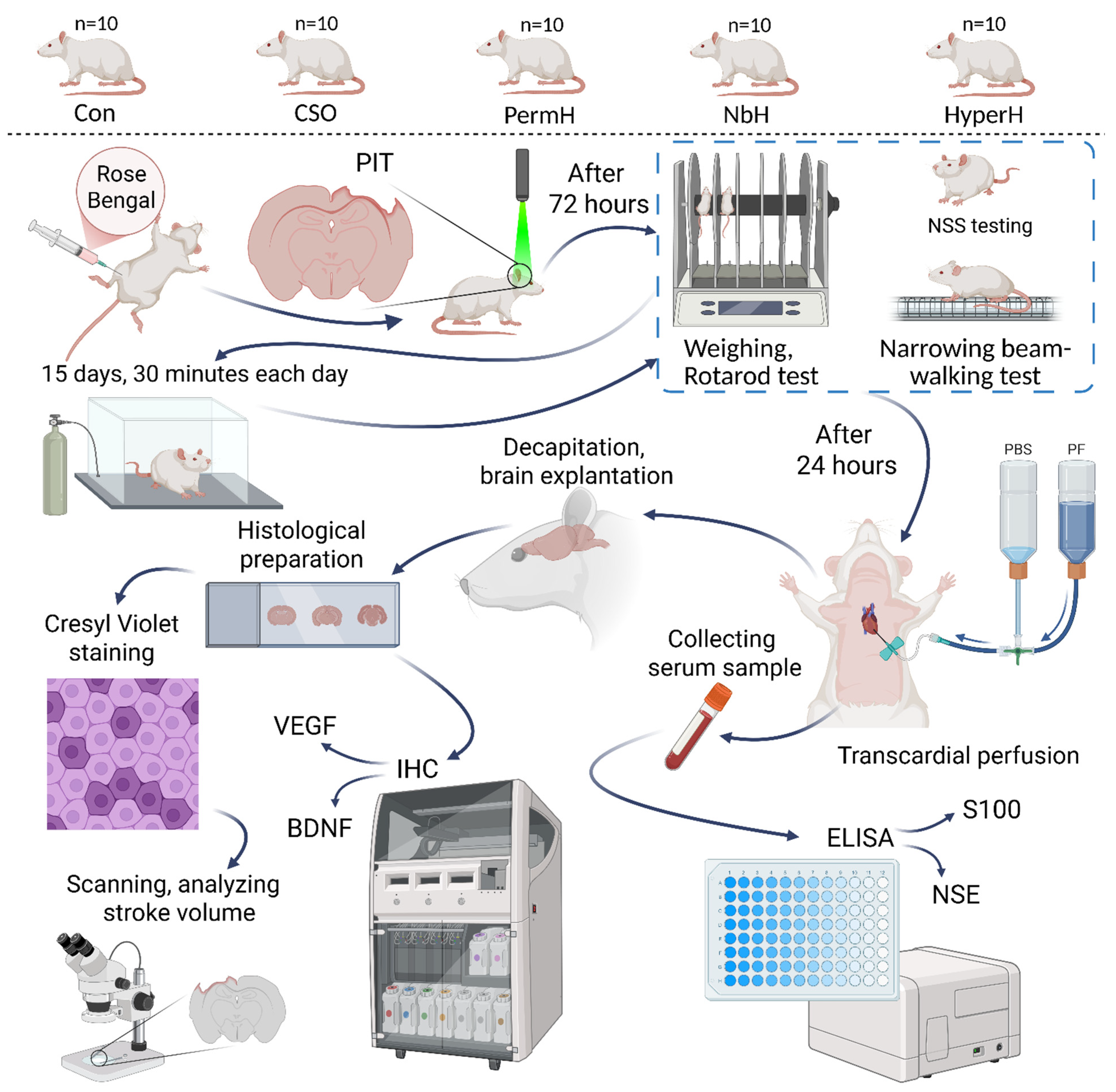

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Groups and Experimental Design

- NbH (normobaric hypoxia): PO2 ≈ 90 mmHg, PCO2 ≈ 1 mmHg, and balance—nitrogen (N2).

- PermH (permissive hypercapnia): PO2 ≈ 150 mmHg, PCO2 ≈ 50 mmHg, and balance—N2.

- HyperH (hypercapnic hypoxia): PO2 ≈ 90 mmHg, PCO2 ≈ 50 mmHg, and balance—N2.

- Con (control group): PO2 ≈ 150 mmHg, PCO2 ≈ 1 mmHg, and balance—N2. Animals underwent all experimental procedures except gas exposure and breathed atmospheric air in the flow chamber.

- CSO (control, sham-operated): PO2 ≈ 150 mmHg, PCO2 ≈ 1 mmHg, and balance—N2. These animals underwent all procedures but received an injection of saline instead of Rose Bengal, thus not undergoing photochemically induced thrombosis (PIT); therefore, ischemia was not induced in this group. Animals breathed atmospheric air. The CSO group serves as an additional control of normal rat neural tissue during histological evaluation, immunohistochemical analysis, and behavioral testing.

4.3. Assessment of Neurological Deficit and Behavioral Testing

4.3.1. Neurological Severity Score

4.3.2. Narrow Beam Walking Test

- Number of foot placements on the lower board (classified as errors);

- Number of slips (partial or complete paw displacement from the upper to lower board);

- Total number of steps from the starting point to the entrance of the dark compartment.

4.3.3. Rotarod Test

4.4. Respiratory Exposure Protocol

4.5. Surgical Procedure and Photochemically Induced Thrombosis

4.6. Histology and Measurement of Ischemic Lesion Volume

4.6.1. Histological Preparation

4.6.2. Nissl Staining

4.6.3. Infarct Volume Quantification

4.7. Immunohistochemistry

4.8. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CaMKII | Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II |

| CREB | cAMP response element-binding protein |

| HIF | Hypoxia-inducible factor |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| PF | Paraformaldehyde |

| EPR | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| cAMP | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular adhesion molecule 1 |

| IL | Interleukin |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NSE | Neuron-specific enolase |

| NSS | Neurological severity score |

| p.p. | Percentage points |

| PCO2 | Partial pressure of carbon dioxide |

| PO2 | Partial pressure of oxygen |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 |

References

- Yuan, H.; Liu, J.; Gu, Y.; Ji, X.; Nan, G. Intermittent hypoxia conditioning as a potential prevention and treatment strategy for ischemic stroke: Current evidence and future directions. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1067411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, F.R.; Ran, R.; Lu, A.; Tang, Y.; Strauss, K.I.; Glass, T.; Ardizzone, T.; Bernaudin, M. Hypoxic preconditioning protects against ischemic brain injury. NeuroRx 2004, 1, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrogrande, G.; Zalewska, K.; Zhao, Z.; Johnson, S.J.; Nilsson, M.; Walker, F.R. Low Oxygen Post Conditioning as an Efficient Non-pharmacological Strategy to Promote Motor Function After Stroke. Transl. Stroke Res. 2019, 10, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprick, J.D.; Mallet, R.T.; Przyklenk, K.; Rickards, C.A. Ischaemic and hypoxic conditioning: Potential for protection of vital organs. Exp. Physiol. 2019, 104, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Zhao, M. Therapeutic hypercapnia improves functional recovery and attenuates injury via antiapoptotic mechanisms in a rat focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion model. Brain Res. 2013, 1533, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruimboom, L.; Muskiet, F.A.J. Intermittent living: The use of ancient challenges as a vaccine against the deleterious effects of modern life—A hypothesis. Med. Hypotheses 2018, 120, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulikov, V.P.; Bespalov, A.G.; Yakushev, N.N. The effectiveness of training with hypercapnic hypoxia in the rehabilitation of ischemic brain damage in the experiment. Bull. Restor. Med. 2008, 2, 59–61. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kulikov, V.P.; Tregub, P.P.; Bespalov, A.G.; Vvedenskiy, A.J. Comparative efficacy of hypoxia, hypercapnia and hypercapnic hypoxia increases body resistance to acute hypoxia in rats. Patol. Fiziol. Eksp. Ter. 2013, 3, 59–61. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tregub, P.; Kulikov, V.; Motin, Y.; Bespalov, A.; Osipov, I. Combined exposure to hypercapnia and hypoxia provides its maximum neuroprotective effect during focal ischemic injury in the brain. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2015, 24, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alekseeva, T.M.; Topuzova, M.P.; Kulikov, V.P.; Kovzelev, P.D.; Kosenko, M.G.; Tregub, P.P. Hypercapnic hypoxia as a method of rehabilitation of patients after ischemic stroke. Neurol. Res. 2024, 46, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tregub, P.P.; Kulikov, V.P.; Ibrahimli, I.; Tregub, O.F.; Volodkin, A.V.; Ignatyuk, M.A.; Kostin, A.A.; Atiakshin, D.A. Molecular Mechanisms of Neuroprotection after the Intermittent Exposures of Hypercapnic Hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bespalov, A.G.; Tregub, P.P.; Kulikov, V.P.; Pijanzin, A.I.; Belousov, A.A. The role of VEGF, HSP-70 and protein S-100B in the potentiation effect of the neuroprotective effect of hypercapnic hypoxia. Patol. Fiziol. Eksp. Ter. 2014, 2, 24–27. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Varis, N.; Leinonen, A.; Parkkola, K.; Leino, T.K. Hyperventilation and Hypoxia Hangover During Normobaric Hypoxia Training in Hawk Simulator. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 942249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasso Pirot, A.; Fritz, K.I.; Ashraf, Q.M.; Mishra, O.P.; Delivoria-Papadopoulos, M. Effects of severe hypocapnia on expression of bax and bcl-2 proteins, DNA fragmentation, and membrane peroxidation products in cerebral cortical mitochondria of newborn piglets. Neonatology 2007, 91, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudellari, A.; Dudek, P.; Marino, L.; Badenes, R.; Bilotta, F. Ventilation Targets for Patients Undergoing Mechanical Thrombectomy for Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A.M.; Mody, I. Changes in hippocampal neuronal activity during and after unilateral selective hippocampal ischemia in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, C.; Lacal, P.M.; Barbaccia, M.L.; Mercuri, N.B.; Graziani, G.; Ledonne, A. The VEGFs/VEGFRs system in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: Pathophysiological roles and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 201, 107101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.G.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Davies, K.; Powers, C.; van Bruggen, N.; Chopp, M. VEGF enhances angiogenesis and promotes blood-brain barrier leakage in the ischemic brain. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 106, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkaya, M.; Cho, S. Genetics of stroke recovery: BDNF val66met polymorphism in stroke recovery and its interaction with aging. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 126, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rroji, O.; Mucignat, C. Factors influencing brain recovery from stroke via possible epigenetic changes. Future Sci. OA 2024, 10, 2409609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwoździńska, P.; Buchbinder, B.A.; Mayer, K.; Herold, S.; Morty, R.E.; Seeger, W.; Vadász, I. Hypercapnia Impairs ENaC Cell Surface Stability by Promoting Phosphorylation, Polyubiquitination and Endocytosis of β-ENaC in a Human Alveolar Epithelial Cell Line. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galganska, H.; Jarmuszkiewicz, W.; Galganski, L. Carbon dioxide inhibits COVID-19-type proinflammatory responses through extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2, novel carbon dioxide sensors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 8229–8242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikov, V.P.; Tregub, P.P.; Kovzelev, P.D.; Dorokhov, E.A.; Belousov, A.A. Hypercapnia--alternative hypoxia signal incentives to increase HIF-1α and erythropoietin in the brain. Patol. Fiziol. Eksp. Ter. 2015, 3, 34–37. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Tregub, P.P.; Malinovskaya, N.A.; Morgun, A.V.; Osipova, E.D.; Kulikov, V.P.; Kuzovkov, D.A.; Kovzelev, P.D. Hypercapnia potentiates HIF-1α activation in the brain of rats exposed to intermittent hypoxia. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2020, 278, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, P.D.; Holliday, P.M.; Fenyk, S.; Hess, K.C.; Gray, M.A.; Hodgson, D.R.; Cann, M.J. Stimulation of mammalian G-protein-responsive adenylyl cyclases by carbon dioxide. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhi, Y.; Jin, Y.; Li, J.; Shi, W.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Yu, S.; Jiang, J.; et al. PKA- and Ca2+-dependent p38 MAPK/CREB activation protects against manganese-mediated neuronal apoptosis. Toxicol. Lett. 2019, 309, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.J.; Hanbali, L.B. Hypoxia upregulates MAPK(p38)/MAPK(ERK) phosphorylation in vitro: Neuroimmunological differential time-dependent expression of MAPKs. Protein Pept. Lett. 2014, 21, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Amiri, M.; Meng, Q.; Unnithan, R.R.; French, C. Calcium Signalling in Neurological Disorders, with Insights from Miniature Fluorescence Microscopy. Cells 2024, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Z.C.; Gray, M.A.; Cann, M.J. Elevated carbon dioxide blunts mammalian cAMP signaling dependent on inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor-mediated Ca2+ release. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 26291–26301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemura, M.; Lecuona, E.; Angulo, M.; Homma, T.; Rodríguez, D.A.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, F.J.; Welch, L.C.; Amarelle, L.; Kim, S.J.; Kaminski, N.; et al. Hypercapnia increases airway smooth muscle contractility via caspase-7-mediated miR-133a-RhoA signaling. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishio, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Takeshita, K.; Aoki, T.; Kudo, H.; Sato, N.; Naoki, K.; Miyao, N.; Ishii, M.; Yamaguchi, K. Effects of hypercapnia and hypocapnia on [Ca2+]i mobilization in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001, 90, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Pulliam, T.L.; Han, J.J.; Xu, J.; Recio, C.V.; Wilkenfeld, S.R.; Shi, Y.; Kushwaha, M.; Bench, S.; Ruiz, E.; et al. Cholesterol metabolism regulated by CAMKK2-CREB signaling promotes castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dong, S.; Quan, S.; Ding, S.; Zhou, X.; Yu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Huang, W.; Shi, Q.; Li, Q. Nuciferine reduces inflammation induced by cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury through the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB pathway. Phytomedicine 2024, 125, 155312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Jin, Y.; Chen, X.; Ye, X.; Shen, X.; Lin, M.; Zeng, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, J. NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy: New insights and translational implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, C.E.; Scholz, C.C.; Rodriguez, J.; Selfridge, A.C.; von Kriegsheim, A.; Cummins, E.P. Carbon dioxide-dependent regulation of NF-κB family members RelB and p100 gives molecular insight into CO2-dependent immune regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 11561–11571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.E.; Wu, S.Y.; Chu, S.J.; Tzeng, Y.S.; Peng, C.K.; Lan, C.C.; Perng, W.C.; Wu, C.P.; Huang, K.L. Pre-Treatment with Ten-Minute Carbon Dioxide Inhalation Prevents Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Lung Injury in Mice via Down-Regulation of Toll-Like Receptor 4 Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Casalino-Matsuda, S.M.; Nair, A.; Buchbinder, A.; Budinger, G.R.S.; Sporn, P.H.S.; Gates, K.L. A role for heat shock factor 1 in hypercapnia-induced inhibition of inflammatory cytokine expression. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 3614–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, M.; Zeng, H. Treatment with 7% and 10% CO2 Enhanced Expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in Hypoxic Cultures of Human Whole Blood. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060520912105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, D.; Totapally, B.R.; Raszynski, A.; Ramachandran, C.; Torbati, D. The Effects of CO2 on Cytokine Concentrations in Endotoxin-Stimulated Human Whole Blood. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 36, 2823–2827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-L.; Ji, X.-P.; Liu, Z.; Liu, G.; Guan, F.-L. Effects of Hypercapnia on Nuclear Factor-κB and TNF-α in Acute Lung Injury Models. Zhongguo Ying Yong Sheng Li Xue Za Zhi 2004, 20, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Phelan, D.E.; Mota, C.; Strowitzki, M.J.; Shigemura, M.; Sznajder, J.I.; Crowe, L.; Masterson, J.C.; Hayes, S.E.; Reddan, B.; Yin, X.; et al. Hypercapnia alters mitochondrial gene expression and acylcarnitine production in monocytes. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2023, 101, 556–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitta, K.; Meybohm, P.; Bein, B.; Heinrich, C.; Renner, J.; Cremer, J.; Steinfath, M.; Scholz, J.; Albrecht, M. Serum from patients undergoing remote ischemic preconditioning protects cultured human intestinal cells from hypoxia-induced damage: Involvement of matrixmetalloproteinase-2 and -9. Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeev, A.D.; Kritskaya, K.A.; Fedotova, E.I.; Berezhnov, A.V. “One Small Step for Mouse”: High CO2 Inhalation as a New Therapeutic Strategy for Parkinson’s Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.M.; Chen, C.L.; Niu, K.C.; Lin, C.H.; Tang, L.Y.; Lin, L.S.; Chang, C.P. Hypobaric hypoxia preconditioning protects against hypothalamic neuron apoptosis in heat-exposed rats by reversing hypothalamic overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and ischemia. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 2622–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, D.; Lu, M.; Chopp, M. Therapeutic benefit of intravenous administration of bone marrow stromal cells after cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke 2001, 32, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, A.D.; Parekh, A.; Patel, Z.H. Methods for evaluating gait associated dynamic balance and coordination in rodents. Behav. Brain Res. 2024, 456, 114695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balduini, W.; De Angelis, V.; Mazzoni, E.; Cimino, M. Long-lasting behavioral alterations following a hypoxic/ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats. Brain Res. 2000, 859, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiner, S.; Wurm, F.; Kunze, A.; Witte, O.W.; Redecker, C. Rehabilitative therapies differentially alter proliferation and survival of glial cell populations in the perilesional zone of cortical infarcts. Glia 2008, 56, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, R.B.; Holleran, S.; Ramakrishnan, R. Sample Size Determination. ILAR J. 2002, 43, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Slipping Index | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forelimbs | Hindlimbs | |||||||

| After Stroke | After Treatment | Before and After Treatment | Compared with Control | After Stroke | After Treatment | Before and After Treatment | Compared with Control | |

| Con | 18.47 | 17.59 | 95% | - | 23.21 | 25 | 108% | - |

| NbH | 22.12 | 15.52 | 70% * | 88% | 30.77 | 23.21 | 75% * | 93% |

| PermH | 34.84 | 24.89 | 71% | 142% | 33.7 | 37.82 | 112% | 151% |

| HyperH | 15.56 | 12.5 | 80% * | 71% | 23.64 | 16.95 | 72% * | 68% |

| CSO | 19 | 17.65 | 93% | 100% | 24.97 | 23.28 | 93% | 93% |

| After Stroke | After Treatment | Before and After Treatment | Compared with Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Con | 128.7 | 117.9 | 92% | - |

| NbH | 151.15 | 78.625 | 52% * | 67% |

| PermH | 118.95 | 110.6 | 93% | 94% |

| HyperH | 138.65 | 142.3 | 103% | 121% |

| CSO | 137 | 138.6333 | 101% | 118% * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tregub, P.P.; Chekulaev, P.A.; Zembatov, G.M.; Namiot, E.D.; Ignatyuk, M.A.; Atiakshin, D.A.; Berdnikov, A.K.; Manasova, Z.S.; Litvitskiy, P.F.; Kulikov, V.P. Neuroplastic Effects Induced by Hypercapnic Hypoxia in Rat Focal Ischemic Stroke Are Driven via BDNF and VEGF Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412019

Tregub PP, Chekulaev PA, Zembatov GM, Namiot ED, Ignatyuk MA, Atiakshin DA, Berdnikov AK, Manasova ZS, Litvitskiy PF, Kulikov VP. Neuroplastic Effects Induced by Hypercapnic Hypoxia in Rat Focal Ischemic Stroke Are Driven via BDNF and VEGF Signaling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412019

Chicago/Turabian StyleTregub, Pavel P., Pavel A. Chekulaev, Georgy M. Zembatov, Eugenia D. Namiot, Michael A. Ignatyuk, Dmitrii A. Atiakshin, Arseniy K. Berdnikov, Zaripat Sh. Manasova, Peter F. Litvitskiy, and Vladimir P. Kulikov. 2025. "Neuroplastic Effects Induced by Hypercapnic Hypoxia in Rat Focal Ischemic Stroke Are Driven via BDNF and VEGF Signaling" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412019

APA StyleTregub, P. P., Chekulaev, P. A., Zembatov, G. M., Namiot, E. D., Ignatyuk, M. A., Atiakshin, D. A., Berdnikov, A. K., Manasova, Z. S., Litvitskiy, P. F., & Kulikov, V. P. (2025). Neuroplastic Effects Induced by Hypercapnic Hypoxia in Rat Focal Ischemic Stroke Are Driven via BDNF and VEGF Signaling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412019