The Disruption of Cyp7b1 Controls IGFBP2 and Prediabetes Exerted Through Different Hydroxycholesterol Metabolites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Modification of the Cyp7b1 Gene in Rat Zygotes

2.2. Plasma Lipid and Lipoprotein Profiles of Male Cyp7b1-Deficient Rats Fed Regular Chow

2.3. Characterization of Secreted Plasma Lipids and Lipoprotein Profiles of Rats Lacking CYP7B1

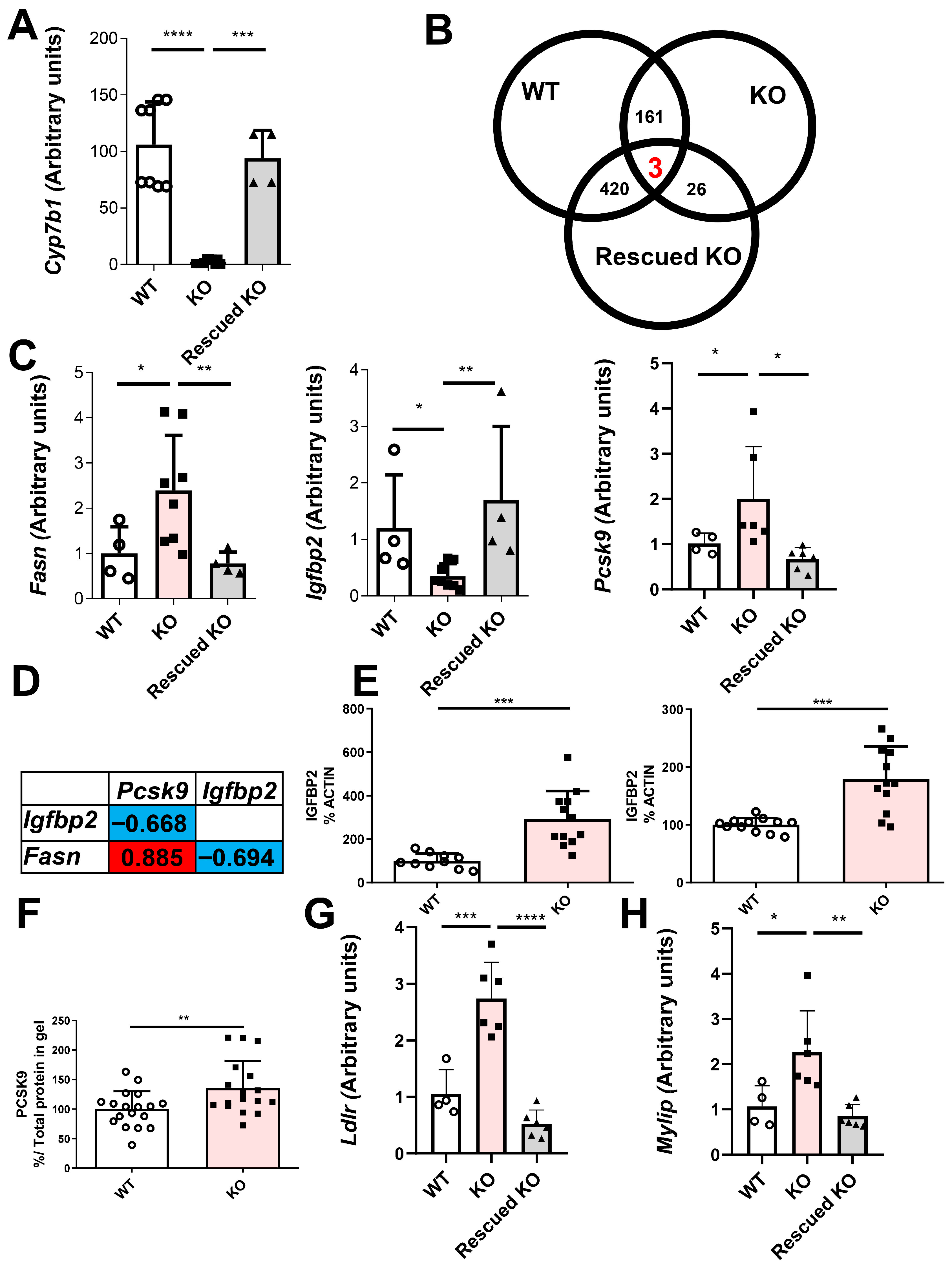

2.4. Mechanisms of Increased Hepatic Secretion of VLDL in Rats Lacking CYP7B1

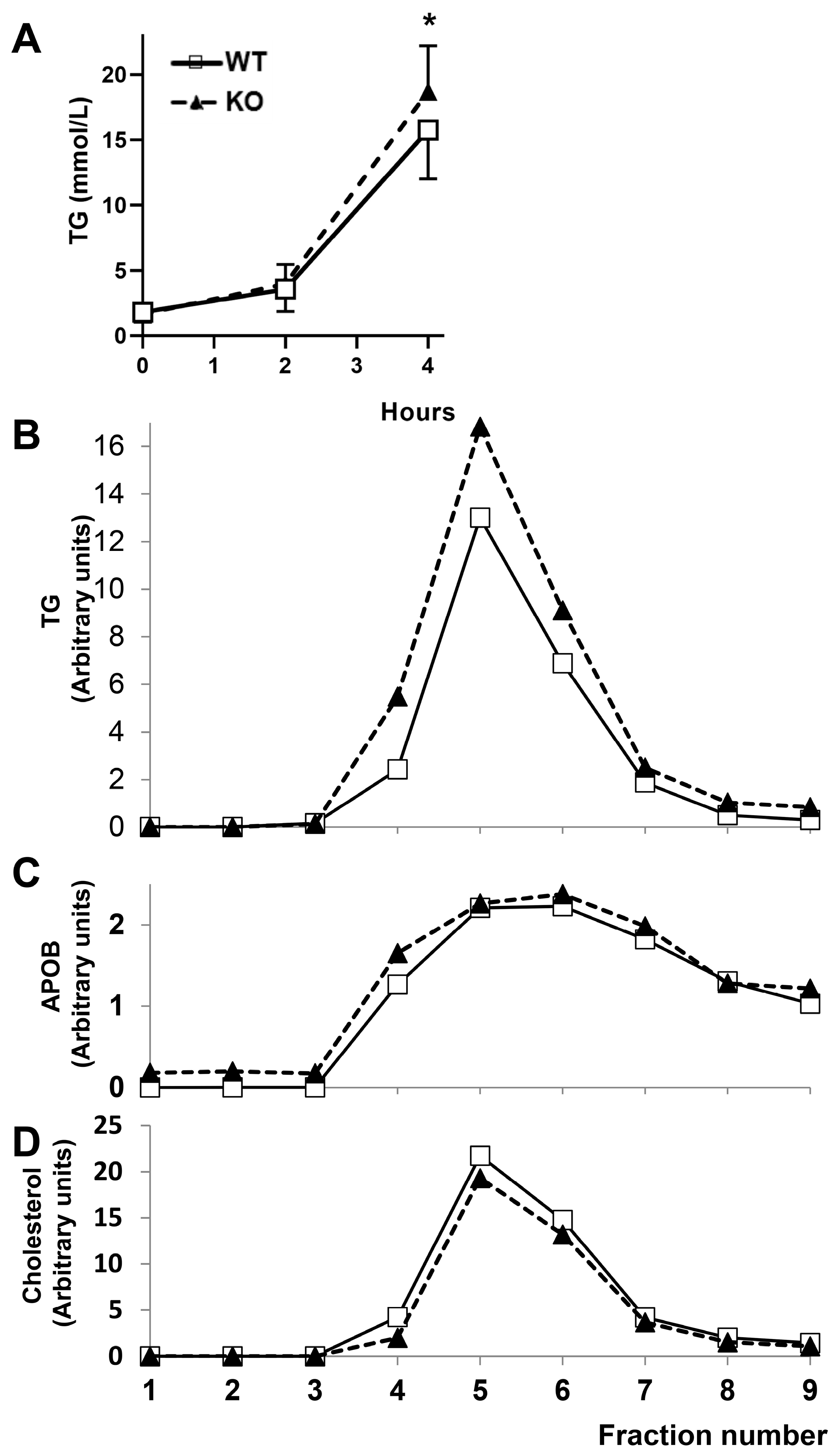

2.5. Response to a Fat Gavage

2.6. Response to Oral Glucose Tolerance Tests in Rats

2.7. Search for Hepatocyte-Specific Targets of Cyp7b1 Deficiency in Rats

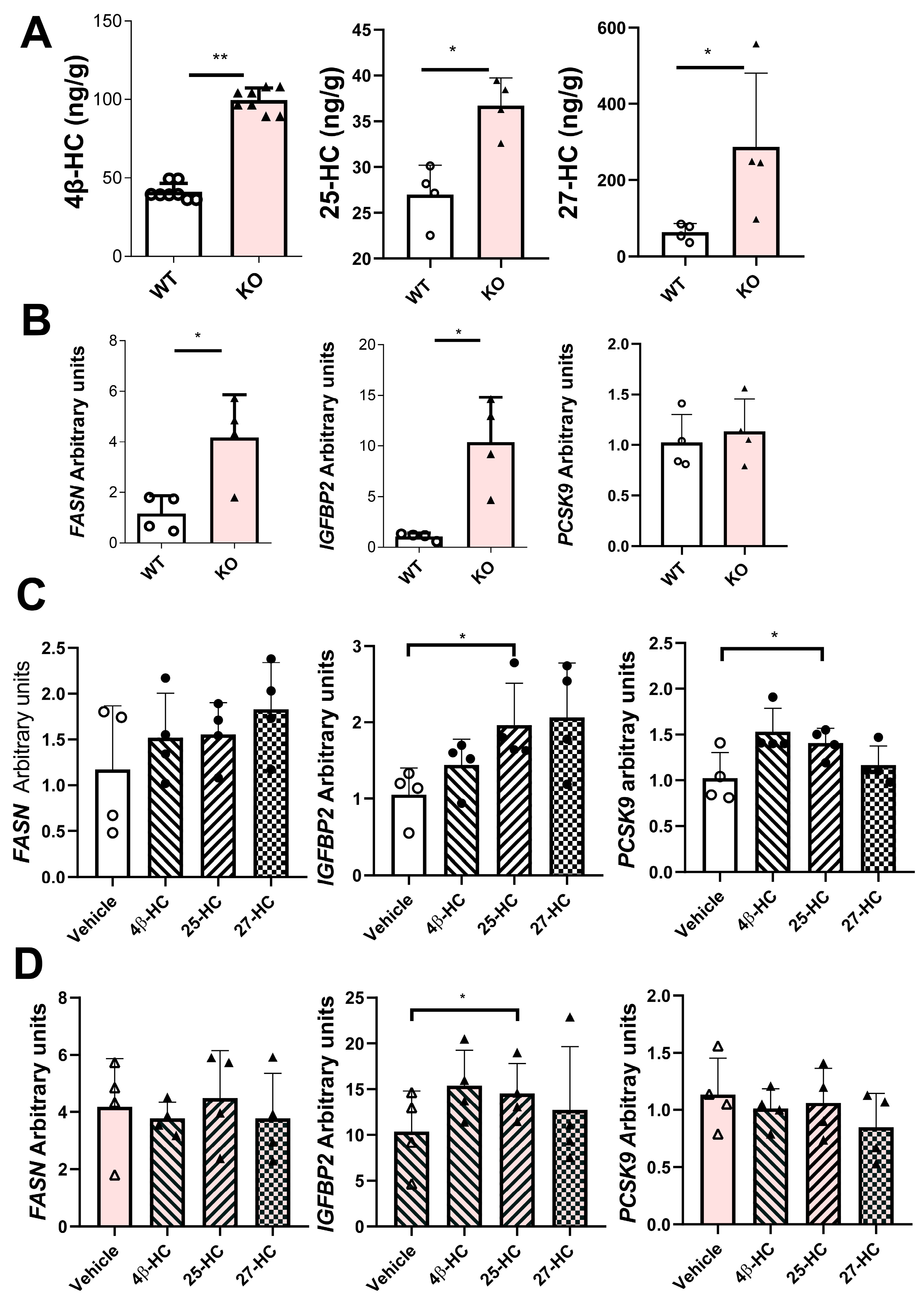

2.8. Characterization of a Stable Human CYP7B1-Knockout HepG2 Cell Line

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Inactivation of Cyp7b1 Gene

4.2. Rats and Diets

4.3. Plasma Analyses

4.4. Analysis of Oxysterols by Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (LC/MS) in the Liver and HepG2 Cell Line

4.5. Histological Analyses

4.6. Fat Tolerance Test

4.7. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

4.8. Quantification of mRNA

4.9. Triglyceride Secretion Rate

4.10. Microsomal and Plasma Membrane Preparations and Western Blot Analyses

4.11. Hepatic Rescue of Cyp7b1-Deficient Rats

4.12. RNAseq

4.13. HepG2 Incubations

4.14. Generation of a Stable CYP7B1 Knockout HepG2 Cell Line

4.15. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALAT | alanine aminotransferase |

| ASAT | aspartate aminotransferase |

| 25-HC | 25-hydroxycholesterol |

| 27-HC | 27-hydroxycholesterol |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| LDLR | low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| LRP1 | low-density lipoprotein receptor related protein 1 |

| SDC1 | syndecan 1 |

References

- Stiles, A.R.; McDonald, J.G.; Bauman, D.R.; Russell, D.W. CYP7B1: One cytochrome P450, two human genetic diseases, and multiple physiological functions. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 28485–28489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorbek, G.; Lewinska, M.; Rozman, D. Cytochrome P450s in the synthesis of cholesterol and bile acids—From mouse models to human diseases. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 1516–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandak, W.M.; Kakiyama, G. The acidic pathway of bile acid synthesis: Not just an alternative pathway. Liver Res. 2019, 3, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Taylor, R.E.; Guo, G.L. In vivo mouse models to study bile acid synthesis and signaling. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2023, 22, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Bean, R.; Rose, K.; Habib, F.; Seckl, J. cyp7b1 catalyses the 7alpha-hydroxylation of dehydroepiandrosterone and 25-hydroxycholesterol in rat prostate. Biochem. J. 2001, 355, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Hawkins, J.; Lund, E.G.; Turley, S.D.; Russell, D.W. Disruption of the oxysterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 16536–16542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.; Allan, A.; Gauldie, S.; Stapleton, G.; Dobbie, L.; Dott, K.; Martin, C.; Wang, L.; Hedlund, E.; Seckl, J.R.; et al. Neurosteroid hydroxylase CYP7B: Vivid reporter activity in dentate gyrus of gene-targeted mice and abolition of a widespread pathway of steroid and oxysterol hydroxylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 23937–23944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, H.; Lundqvist, J.; Norlin, M. Effects of CYP7B1-mediated catalysis on estrogen receptor activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1801, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omoto, Y.; Lathe, R.; Warner, M.; Gustafsson, J.A. Early onset of puberty and early ovarian failure in CYP7B1 knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 2814–2819, Erratum in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 8298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihua, Z.; Lathe, R.; Warner, M.; Gustafsson, J.A. An endocrine pathway in the prostate, ERbeta, AR, 5alpha-androstane-3beta,17beta-diol, and CYP7B1, regulates prostate growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13589–13594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Martin, K.O.; Javitt, N.B.; Chiang, J.Y. Structure and functions of human oxysterol 7alpha-hydroxylase cDNAs and gene CYP7B1. J. Lipid Res. 1999, 40, 2195–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennebert, O.; Chalbot, S.; Alran, S.; Morfin, R. Dehydroepiandrosterone 7alpha-hydroxylation in human tissues: Possible interference with type 1 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-mediated processes. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007, 104, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, C.; Pompon, D.; Urban, P.; Morfin, R. Inter-conversion of 7alpha- and 7beta-hydroxy-dehydroepiandrosterone by the human 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006, 99, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoldi, A.; Crimella, C.; Tenderini, E.; Martinuzzi, A.; D’Angelo, M.G.; Musumeci, O.; Toscano, A.; Scarlato, M.; Fantin, M.; Bresolin, N.; et al. Clinical phenotype variability in patients with hereditary spastic paraplegia type 5 associated with CYP7B1 mutations. Clin. Genet. 2012, 81, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Torre, P.; Garcia Galloway, E.; Lopez-Sendon Moreno, J.L. Hereditary spastic paraparesis due to SPG5/CYP7B1 mutation with potential therapeutic implications. Neurologia 2023, 38, 710–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pass, G.J.; Becker, W.; Kluge, R.; Linnartz, K.; Plum, L.; Giesen, K.; Joost, H.G. Effect of hyperinsulinemia and type 2 diabetes-like hyperglycemia on expression of hepatic cytochrome p450 and glutathione s-transferase isoforms in a New Zealand obese-derived mouse backcross population. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002, 302, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Menke, J.G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, G.; MacNaul, K.L.; Wright, S.D.; Sparrow, C.P.; Lund, E.G. 27-hydroxycholesterol is an endogenous ligand for liver X receptor in cholesterol-loaded cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 38378–38387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umetani, M.; Domoto, H.; Gormley, A.K.; Yuhanna, I.S.; Cummins, C.L.; Javitt, N.B.; Korach, K.S.; Shaul, P.W.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. 27-Hydroxycholesterol is an endogenous SERM that inhibits the cardiovascular effects of estrogen. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, D.R.; Bitmansour, A.D.; McDonald, J.G.; Thompson, B.M.; Liang, G.; Russell, D.W. 25-Hydroxycholesterol secreted by macrophages in response to Toll-like receptor activation suppresses immunoglobulin A production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 16764–16769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.; Saint-Pol, J.; Dib, S.; Pot, C.; Gosselet, F. 25-Hydroxycholesterol in health and diseases. J. Lipid Res. 2024, 65, 100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philipeaux, J.M. Note sur l’extirpation des capsules servenales chez les rats albios (Mus Rattus). Comptes Rendus Hebd. Seances L’academie Sci. 1856, 43, 904–906. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, M.J. Comparative analysis of mammalian plasma lipoproteins. Methods Enzym. 1986, 128, 70–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greeve, J.; Altkemper, I.; Dieterich, J.H.; Greten, H.; Windler, E. Apolipoprotein B mRNA editing in 12 different mammalian species: Hepatic expression is reflected in low concentrations of apoB-containing plasma lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 1993, 34, 1367–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietschy, J.M.; Turley, S.D.; Spady, D.K. Role of liver in the maintenance of cholesterol and low density lipoprotein homeostasis in different animal species, including humans. J. Lipid Res. 1993, 34, 1637–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrosova, I.G.; Drel, V.R.; Kumagai, A.K.; Szábo, C.; Pacher, P.; Stevens, M.J. Early diabetes-induced biochemical changes in the retina: Comparison of rat and mouse models. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2525–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NLM Genome Assembly GRCr8. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_036323735.1/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Ishibashi, S.; Brown, M.S.; Goldstein, J.L.; Gerard, R.D.; Hammer, R.E.; Herz, J. Hypercholesterolemia in low density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice and its reversal by adenovirus-mediated gene delivery. J. Clin. Investig. 1993, 92, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishibashi, S.; Herz, J.; Maeda, N.; Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. The two-receptor model of lipoprotein clearance: Tests of the hypothesis in “knockout” mice lacking the low density lipoprotein receptor, apolipoprotein E, or both proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 4431–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, D.; Chen, C.; Han, S.; Ganda, A.; Murphy, A.J.; Haeusler, R.; Thorp, E.; Accili, D.; Horton, J.D.; Tall, A.R. Regulation of hepatic LDL receptors by mTORC1 and PCSK9 in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauzier, C.; Lamarche, B.; Tremblay, A.J.; Couture, P.; Picard, F. Associations between insulin-like growth factor binding protein-2 and lipoprotein kinetics in men. J. Lipid Res. 2022, 63, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Chung, S.; Shelness, G.S.; Parks, J.S. Hepatic ABCA1 deficiency is associated with delayed apolipoprotein B secretory trafficking and augmented VLDL triglyceride secretion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2017, 1862, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, K.I.; Bishop, J.R.; Foley, E.M.; Gonzales, J.C.; Niesman, I.R.; Witztum, J.L.; Esko, J.D. Syndecan-1 is the primary heparan sulfate proteoglycan mediating hepatic clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 3236–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quazi, F.; Molday, R.S. Differential phospholipid substrates and directional transport by ATP-binding cassette proteins ABCA1, ABCA7, and ABCA4 and disease-causing mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 34414–34426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segrest, J.P.; Tang, C.; Song, H.D.; Jones, M.K.; Davidson, W.S.; Aller, S.G.; Heinecke, J.W. ABCA1 is an extracellular phospholipid translocase. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Timmins, J.M.; Duong, M.; Degirolamo, C.; Rong, S.; Sawyer, J.K.; Singaraja, R.R.; Hayden, M.R.; Maeda, N.; Rudel, L.L.; et al. Targeted deletion of hepatocyte ABCA1 leads to very low density lipoprotein triglyceride overproduction and low density lipoprotein hypercatabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 12197–12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.L.; Zhang, J.L.; Zheng, Q.C.; Niu, R.J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.X.; Sun, C.C. Structural and dynamic basis of human cytochrome P450 7B1: A survey of substrate selectivity and major active site access channels. Chemistry 2013, 19, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.S.; Jirik, F.R.; LeBoeuf, R.C.; Henderson, H.; Castellani, L.W.; Lusis, A.J.; Ma, Y.; Forsythe, I.J.; Zhang, H.; Kirk, E.; et al. Alteration of lipid profiles in plasma of transgenic mice expressing human lipoprotein lipase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 11417–11424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, N.; Li, H.; Lee, D.; Oliver, P.; Quarfordt, S.H.; Osada, J. Targeted disruption of the apolipoprotein C-III gene in mice results in hypotriglyceridemia and protection from postprandial hypertriglyceridemia. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 23610–23616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Geurts, A.M.; Poirier, C.; Petit, D.C.; Harrison, W.; Overbeek, P.A.; Bishop, C.E. Generation of rat mutants using a coat color-tagged Sleeping Beauty transposon system. Mamm. Genome 2007, 18, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, M.A.; Carpintero, R.; Acin, S.; Arbones-Mainar, J.M.; Calleja, L.; Carnicer, R.; Surra, J.C.; Guzman-Garcia, M.A.; Gonzalez-Ramon, N.; Iturralde, M.; et al. Immune-regulation of the apolipoprotein A-I/C-III/A-IV gene cluster in experimental inflammation. Cytokine 2005, 31, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, L.; Paris, M.A.; Paul, A.; Vilella, E.; Joven, J.; Jimenez, A.; Beltran, G.; Uceda, M.; Maeda, N.; Osada, J. Low-cholesterol and high-fat diets reduce atherosclerotic lesion development in ApoE-knockout mice. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999, 19, 2368–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Beamonte, R.; Navarro, M.A.; Acin, S.; Guillen, N.; Barranquero, C.; Arnal, C.; Surra, J.; Osada, J. Postprandial changes in high density lipoproteins in rats subjected to gavage administration of virgin olive oil. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendiara, I.; Domeno, C.; Nerin, C.; Geurts, A.M.; Osada, J.; Martinez-Beamonte, R. Determination of total plasma oxysterols by enzymatic hydrolysis, solid phase extraction and liquid chromatography coupled to mass-spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 150, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.L.; Spicer, M.T.; Spicer, L.J. Effect of high-fat diet on body composition and hormone responses to glucose tolerance tests. Endocrine 2002, 19, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Beamonte, R.; Navarro, M.A.; Larraga, A.; Strunk, M.; Barranquero, C.; Acin, S.; Guzman, M.A.; Inigo, P.; Osada, J. Selection of reference genes for gene expression studies in rats. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 151, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Knapik, S.; Pastor, O.; Barranquero, C.; Herrera Marcos, L.V.; Guillen, N.; Arnal, C.; Gascon, S.; Navarro, M.A.; Rodriguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Busto, R.; et al. Hepatic Synaptotagmin 1 is involved in the remodelling of liver plasma- membrane lipid composition and gene expression in male Apoe-deficient mice consuming a Western diet. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2020, 1865, 158790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillen, N.; Acin, S.; Surra, J.C.; Arnal, C.; Godino, J.; Garcia-Granados, A.; Muniesa, P.; Ruiz-Gutierrez, V.; Osada, J. Apolipoprotein E determines the hepatic transcriptional profile of dietary maslinic acid in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009, 20, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Song, Y.; Liu, D. Hydrodynamics-based transfection in animals by systemic administration of plasmid DNA. Gene Ther. 1999, 6, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Budker, V.; Wolff, J.A. High levels of foreign gene expression in hepatocytes after tail vein injections of naked plasmid DNA. Hum. Gene Ther. 1999, 10, 1735–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 2011, 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrera-Marcos, L.V.; Sancho-Knapik, S.; Gabas-Rivera, C.; Barranquero, C.; Gascon, S.; Romanos, E.; Martinez-Beamonte, R.; Navarro, M.A.; Surra, J.C.; Arnal, C.; et al. Pgc1a is responsible for the sex differences in hepatic Cidec/Fsp27beta mRNA expression in hepatic steatosis of mice fed a Western diet. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 318, E249–E261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Wild-Type (n = 5) | Homozygous Cyp7b1-KO (n = 7) | |

|---|---|---|

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 115 ± 33 | 117 ± 26 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 263 ± 177 | 368 ± 99 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 114 ± 33 | 111 ± 24 |

| VLDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1 ± 0.4 | 5 ± 1 *** |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 118 ± 59 | 194 ± 26 * |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.1 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| ALAT (IU/L) | 53 ± 15 | 79 ± 27 |

| ASAT (IU/L) | 106 ± 31 | 102 ± 40 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.3 ± 0.5 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (IU/L) | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.6 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Guillén, N.; Sánchez-Marco, J.; Herrera-Marcos, L.V.; Surra, J.C.; Navarro, M.A.; Barranquero, C.; Arnal, C.; Puente, J.J.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; et al. The Disruption of Cyp7b1 Controls IGFBP2 and Prediabetes Exerted Through Different Hydroxycholesterol Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411994

Martínez-Beamonte R, Guillén N, Sánchez-Marco J, Herrera-Marcos LV, Surra JC, Navarro MA, Barranquero C, Arnal C, Puente JJ, Rodríguez-Yoldi MJ, et al. The Disruption of Cyp7b1 Controls IGFBP2 and Prediabetes Exerted Through Different Hydroxycholesterol Metabolites. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411994

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Beamonte, Roberto, Natalia Guillén, Javier Sánchez-Marco, Luis V. Herrera-Marcos, Joaquín C. Surra, María A. Navarro, Cristina Barranquero, Carmen Arnal, Juan J. Puente, Ma Jesús Rodríguez-Yoldi, and et al. 2025. "The Disruption of Cyp7b1 Controls IGFBP2 and Prediabetes Exerted Through Different Hydroxycholesterol Metabolites" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411994

APA StyleMartínez-Beamonte, R., Guillén, N., Sánchez-Marco, J., Herrera-Marcos, L. V., Surra, J. C., Navarro, M. A., Barranquero, C., Arnal, C., Puente, J. J., Rodríguez-Yoldi, M. J., Mendiara, I., Domeño, C., Nerín, C., Geurts, A. M., Osada, J., & Laclaustra, M. (2025). The Disruption of Cyp7b1 Controls IGFBP2 and Prediabetes Exerted Through Different Hydroxycholesterol Metabolites. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11994. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411994