Immune Landscape and Application of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Characterization of ccRCC

2.1. Pathological Characterization of ccRCC

2.2. Genomic/Molecular Characterization of ccRCC

2.3. Immune Landscape of ccRCC

3. Development of Therapeutic Treatment for ccRCC

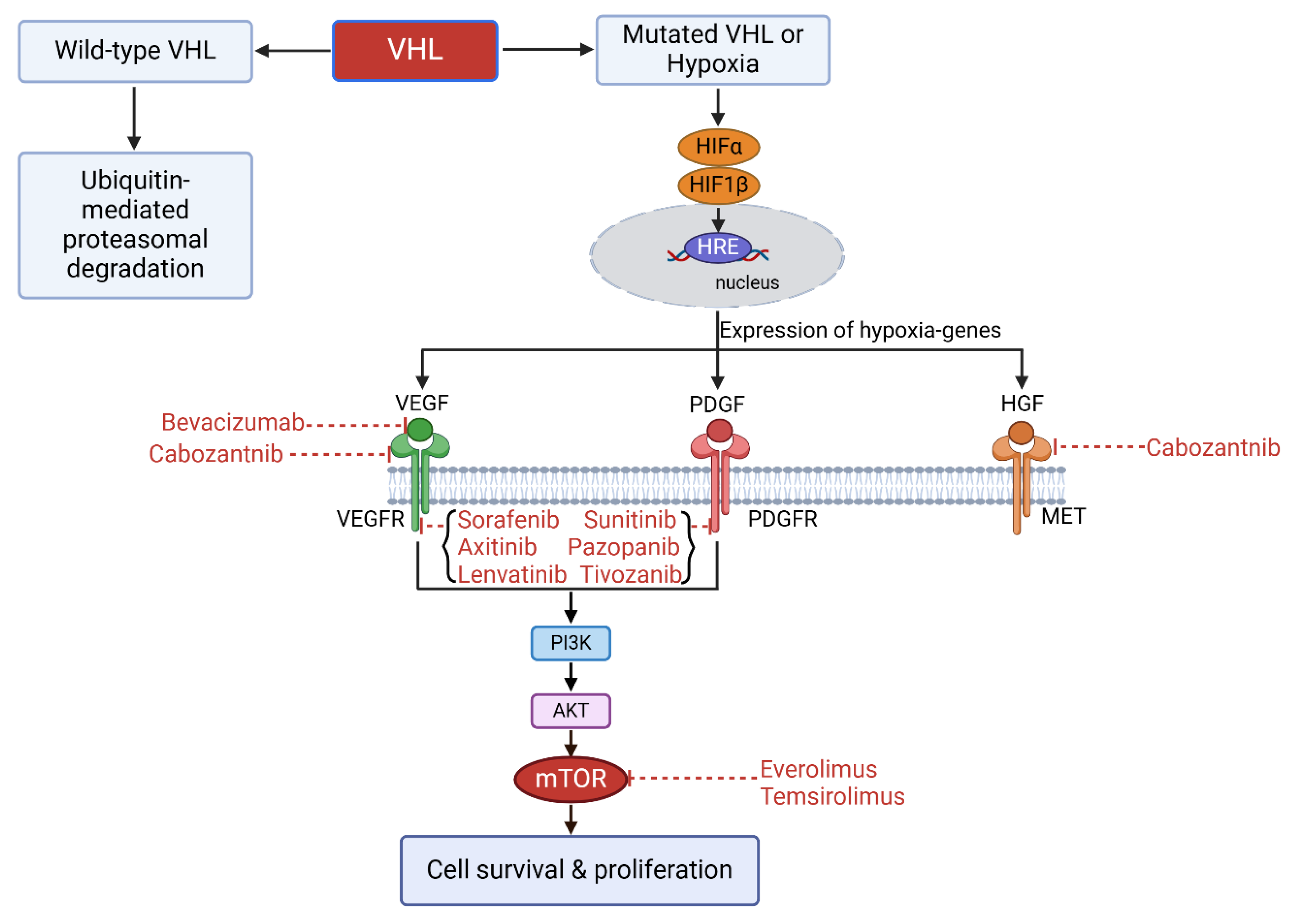

3.1. Targeting Therapy

- Sorafenib is a multi-kinase inhibitor that primarily inhibits VEGFR1, 2, 3, and PDGF receptor (PDGFR). Sorafenib also has an action on newly identified targets CRAF, BRAF, and V600E BRAF. Sorafenib is the first commercialized TKI for metastatic ccRCC and European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved second-line treatment of metastatic ccRCC that was resistant to IL-2 or IFN-α therapy [31,32,33].

- Sunitinib is a multi-kinase inhibitor that primarily inhibits VEGFR1, 2, 3, and PDGFR. Due to a clinical trial in 2007, which shows a better overall response rate (ORR) and a longer progression-free survival (PFS) of sunitinib group compared to IFN-α group, sunitinib/targeted therapy replaced cytokine therapy becoming the standard care for metastatic ccRCC. Sunitinib is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)- and EMA-approved first-line treatment of metastatic ccRCC [34,35,36,37].

- Pazopanib is a multi-kinase inhibitor that primarily inhibits VEGFR1, 2, 3, and PDGFR. It shows a better safety profile without compromising the efficacy compared to sunitinib. Pazopanib is the EMA-approved first-line treatment of metastatic ccRCC. Sunitinib and pazopanib are the favored targeted therapies for the first-line treatment of ccRCC [38,39].

- Axitinib is a second-generation of TKI that selectively targets VEGFR 1, 2, and 3, whose IC50 is of picomolar level and significantly lower than the first-generation of TKIs. Axitinib is an FDA- and EMA-approved second-line treatment of metastatic ccRCC that was resistant to sunitinib or cytokine treatment [40,41,42,43].

- Cabozantinib is a multi-kinase inhibitor that targets VEGFR, mesenchymal epithelial transition factor (MET), and anexelekto (AXL), all of which are commonly upregulated in RCC. Cabozantinib is an FDA- and EMA-approved first-line treatment of metastatic ccRCC with intermediate or poor risk and second-line treatment of metastatic ccRCC that was resistant to anti-VEGF therapy [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

- Tivozanib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is selectively targets VEGFR1, 2, and 3, which works at picomolar level to inhibit VEGFR phosphorylation. It has a better safety profile than the broad-spectrum tyrosine kinase inhibitors and is recommended as a third- or fourth-line treatment for metastatic ccRCC [62].

- Everolimus is a derivative of Rapamycin that binds FK506 binding protein 12 (FKBP12) and inhibits mTOR activity resulting in a G1 growth arrest and decreased levels of both HIFs and VEGF. Everolimus is an oral inhibitor and an EMA-approved first-line treatment of metastatic ccRCC and a recommended drug after the failure of first-line TKI therapy [70,71,72].

- Temsirolimus binds FK506 binding protein 12 (FKBP12) and inhibits mTOR activity resulting in a G1 growth arrest and decreased levels of both HIFs and VEGF. Temsirolimus is administered intravenously. FDA and EMA approved temsirolimus as a first-line treatment of metastatic ccRCC. mTOR inhibitors are more potent in inhibiting cell proliferation than neovascularization [73,74,75].

| Inhibitors | Targets | Mechanisms | Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sorafenib [31,32,33] | VEGFR-1/-2/-3, PDGFR-α/-β, BRAF V600E, c-Raf, c-kit, FLT-3 | blocking RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway and suppressing VEGFR and PDGFR | RCC, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, thyroid cancer, myeloid leukemia |

| Sunitinib [34,35,36,37] | VEGFR-1/-2/-3, PDGFR-α/-β, FLT-3, c-kit | suppressing VEGFR-2 signaling | advanced ccRCC, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, breast cancer, small cell lung cancer |

| Pazopanib [38,39] | VEGFR-1/-2/-3, PDGFR-α/-β, LCK, c-fms, FGFR-1/-3, c-kit | inhibiting VEGFR-2 phosphorylation | advanced RCC, soft tissue sarcoma |

| Axitinib [40,41,42,43] | VEGFR-1/-2/-3, PDGFR, KIT | selectively inhibiting VEGFR-1/-2/-3 signaling | advanced RCC, advanced sarcoma, head and neck malignancies, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer |

| Cabozantinib [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54] | VEGFR-2, MET, RET, AXL, FLT3, c-kit | targeting MET and VEGFR2 | advanced RCC, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, progressive/metastatic medullary thyroid cancer, adrenocortical carcinoma, breast cancer, glioblastoma, non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, ovarian cancer |

| Lenvatinib [55,56,57,58,59,60,61] | VEGFR-1/-2/-3, PDGFR, c-kit, FGFR-1/-2/-3/-4 | dual inhibition of VEGFR1-3 and FGFR1-4 signaling | thyroid carcinoma, unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma, unresectable thymic carcinoma, advanced RCC, |

| Tivozanib [62] | VEGFR-1/-2/-3, c-kit, PDGFR-β | selectively inhibition of VEGFR-1/-2/-3 | advanced RCC |

| Bevacizumab [63,64,65,66,67,68,69] | VEGF | preventing the activation of VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 on endothelial cells | metastatic colorectal cancer, advanced non-small cell lung cancer, metastatic RCC, glioblastoma, advanced cervical cancer, ovarian cancer |

| Everolimus [70,71,72] | mTOR complex 1 | inhibiting mTOR activity, which results in a G1 growth arrest, and decreased levels of HIFs and VEGF | Pancreatic, gastrointestinal, and pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors, RCC, hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer |

| Temsirolimus [73,74,75] | mTOR complex 1 | inhibiting mTOR activity, which results in a G1 growth arrest, and decreased levels of HIFs and VEGF | advanced RCC, mantle cell lymphoma, radio-resistant nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

3.2. Immunotherapy

- ◆

- Cytokine

- ◆

- Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs)

- CTLA-4 expression occurs in a variety of cancers and associates with T cell infiltration [81]. CTLA-4 is homologous to CD28 and expressed on T cells. CTLA-4 competitively recruits CD80/CD86 and forms higher affinity than CD28 that limits its interaction with CD28 and plays an inhibitory role in the regulation of T cell activation [82,83].

- PD-1 expression occurs mainly in activated T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells with an elevated expression in tumor-specific T cells [84]. PD-L1 (a PD-1 ligand) expression occurs on the cell membrane of tumor cells. In general, PD-1 expression decreases as the antigen decreases. However, PD-1 expression increases and leads to T cell exhaustion if the antigen is present for a long time [85]. PD-1 binding to PD-L1 prevents T cell activation and proliferation via inhibition of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-EMK-ERK signaling pathways, which thereby attenuates the killing action of T cells [86]. If PD-1 binding to PD-L1 is blocked, then the state of T cell exhaustion can be restored [87]. PD-L1 and PD-L2 are highly expressed in both primary and metastatic sites in advanced ccRCC [87,88].

- LAG3 (an inhibitory receptor) expression occurs mainly in activated T cells, Tregs, and NK cells [89]. LAG3 binds MHC-II with a high affinity and prevents MHC-II interaction with T cell co-receptor CD4 [90,91]. Dual blockade of LAG3 and PD-L1 results in synergistic anti-tumor effects since LAG3 and PD-L1 co-expression always occurs in tumor-infiltrating T cells [92]. Furthermore, LAG3 and PD-1 combinations are common in activated T cells in ccRCC tissues. Consequently, dual blockage of LAG3 and PD-1 holds promise as an effective ccRCC treatment [93].

- TIGIT (an inhibitory receptor) expression occurs mainly in activated CD8+ or CD4+ T cells, Tregs, and NK cells [94]. CD155, CD112, and CD113 (TIGIT ligands) expression occurs in APCs. CD155 demonstrates the highest affinity for TIGIT among these ligands. TIGIT binding to ligand alters APC function and reduces cytokine release which results in diminished T cell activation [95]. Studies have shown that TIGIT is expressed on exhausted CD8+ T cells, and detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and TILs in ccRCC patients [96].

- TIM3 (a co-inhibitory receptor) expression occurs mainly in IFN-γ-producing T cells, FOXP3+ Treg cells, and innate immune cells [97]. Galectin-9 (TIM3 ligand) is found on the surface of cancer cells or in the parenchyma. TIM3 binding to galectin-9 results in disruption of immune synapse formation and ultimately anergia or apoptosis of T cells. The increase in TIM3 expression results in a suppression of the T cell response and T cell dysfunction, similar to PD-1 [98]. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) that express TIM3 also express PD-1 and TIM3+PD-1+ TILs exhibit a more severe depletion phenotype [99]. Consistent with the above findings, TIM3 and PD1 co-expression on CD8+ T cells results in poor clinical outcomes for ccRCC patients [100].

- VISTA expression occurs in a variety of tumor cells and TILs. It shares a homology with PD-L1 and plays a role in tumor immunosuppression [101]. VISTA serves dual immunosuppressive roles as both a ligand on APCs with PSGL-1 being its receptor on CTLs and a receptor on CTLs with VSIG-3 as its ligand [102]. VISTA interacts with its receptor/ligand, resulting in the inhibition of T cell activation and proliferation, while simultaneously promoting the expression of Foxp3 within the TME [103]. VISTA expression occurs mainly in CD14+HLA−DR+ macrophages and activated CD8+ T cells [104,105], and is significantly increased in ccRCC, even more than PD-L1.

- IDO1 is an amino acid cytosolic haem-containing enzyme involved in the first, rate-limiting step of the tryptophan metabolism to kynurenine. It is associated with increased introtumoral Treg infiltration and impaired cytotoxic T-cell function. IDO1 plays an immunosuppressive role illustrated in two aspects. On one hand, local depletion of Trp results in the activation of the amino-acid-sensitive GCN2 and mTOR stress-kinase pathways, which in turn causes cell cycle arrest and induction of anergy of responding T cells. On the other hand, the downstream Kyns induces effector T-cell arrest or apoptosis and may contribute to the conversion of naive CD4+ T cells into FOXP3+ Treg cells [106]. Moreover, it also contributes to MDSC infiltration and M2 polarization [107].

- TREM2 expression occurs in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) which are immunosuppressive cells in the TME [105]. TAMs cause T cell dysfunction, tolerance to PD1/PD-L1 therapy, and poor clinical outcomes [106]. TAMs that express a high level of TRME2 are more abundant in ccRCC than in normal renal tissue [107]. In this regard, high TRME-2-expressing TAMs are often accompanied by a higher risk of recurrence. Therefore, TRME-2 is a putative therapeutic target for the treatment of ccRCC, and clinical trials using TRME2 blockade therapy are currently ongoing [108].

| Targets | Molecular Properties | Mechanism | Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTLA-4 | expressed on T cells, structurally homologous to CD28 and competitively binds CD80/CD86 | CTLA-4 competes with CD28 for CD80/CD86 binding and acting as an antagonist of CD28-mediated co-stimulation of T cells [81,82,83] | Ipilimumab [108] |

| PD-1 | expression occurs mainly in activated T cells, B cells, and NK cells, and binds PD-L1 and PD-L2 | PD-1 binding to PD-L1 prevents T cell activation and proliferation via inhibition of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-EMK-ERK signaling pathways [86,87] | Nivolumab [109,110,111] Pembrolizumab [112] |

| PD-L1 | expression occurs in tumor cells and binds to PD-1 | PD-1 binding to PD-L1 prevents T cell activation and proliferation via inhibition of the PI3K-AKT-mTOR and Ras-EMK-ERK signaling pathways [86,87] | Avelumab [113] Atezolizumab [114] |

| LAG3 | expression occurs mainly in activated T cells, Tregs, and NK cells | LAG3-MHC-II interface overlaps with the MHC-II-binding site of the CD4, disrupting CD4-MHC-II interactions as a mechanism for LAG3 immunosuppressive function [91] | Relatlimab (NCT02996110) [115] Ieramilimab (NCT05148546) [115] |

| TIGIT | expressed on activated CD8+ or CD4+ T cells, Tregs, and NK cells, and binds CD155, CD112 and CD113 on APC | TIGIT binding to CD155 alters APC function and reduces cytokine release which results in diminished T cell activation [95] | Tiragolumab (NCT03977467) [115] |

| TREM2 | occurs in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) | TREM2 functions as a tumor suppressor and is predominantly expressed in various myeloid cell types, including dendritic cells (DCs), immunosuppressive macrophages, and monocytes. The absence of TREM2 facilitates the phenotypic transformation of macrophages towards the M1 phenotype, accompanied by the increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12, IL-6, IL-15, and TNF. Notably, TREM2 deficiency also enhances the proliferation and activation of both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells [80] | PY314 (NCT04691375) [115] |

| TIM3 | expressed on IFN-γ-producing T cells, FOXP3+ Treg cells, and innate immune cells, and binds to galectin-9 | binding to galectin-9 results in disruption of immune synapse formation and ultimately anergia or apoptosis of T cells [97] | Cobolimab [116] Sabatolimab [117] |

| VISTA | expression occurs in a variety of tumor cells and TILs, sharing homology to PD-L1 | VISTA functions as both a ligand on APCs with PSGL-1 being its receptor on CTLs and a receptor on CTLs with VSIG-3 as its ligand, which potently suppresses activation of T cells [102,103] | HMBD-002 [118] KVA12123 [119] |

| IDO1 | an amino acid cytosolic haem-containing enzyme involved in the first, rate-limiting step of the tryptophan metabolism to kynurenine | 1. Local depletion of Trp results in activation of the amino-acid-sensitive GCN2 and mTOR stress-kinase pathways, which in turn causes cell cycle arrest and induction of anergy of responding T cells. 2. Downstream Kyns induces effector T-cell arrest or apoptosis, and may also contribute to the conversion of naive CD4+ T cells into FOXP3+ Treg cells [106] | Epacadostat [120] Navoximod [121] |

- ◆

- Application of ICIs monotherapy in ccRCC (Table 3)

- ■

- CTLA-4 inhibitor

- ○

- Ipilimumab (a CTLA-4 blocker) is used to treat metastatic ccRCC patients and its efficacy was assessed in a phase II clinical trial (NCT00057889). The results based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) showed the following: 1) 1 of 21 low dose ipilimumab patients had a partial response, 2) 5 of 40 high dose ipilimumab patients had partial responses, and 3) 33% of patients experienced a grade III or IV immune-mediated toxicity. Despite the above-mentioned low overall efficacy of ipilimumab, ipilimumab treatment does induce cancer regression in some metastatic ccRCC patients that were resistant to IL-2 treatment [108].

- ■

- PD-1 inhibitor

- ○

- Nivolumab shows anti-tumor activity and improves the overall survival (OS) of a variety of malignant tumors, including mRCC [111]. The results based on CheckMate 025 phase III clinical trial (NCT01668784) in 2015 led to FDA approval of nivolumab for the treatment of mRCC patients [110]. In this clinical trial, a total of 821 patients who had received sorafenib or sunitinib were randomly assigned to either nivolumab or everolimus (a mTOR inhibitor) treatment. Of a 72-month median follow-up time, the results showed an ORR of 23% vs. 4%, OS of 25.8 months vs. 19.7 months, and a 5-year survival rate of 23% vs. 4% in the nivolumab versus everolimus groups, respectively. In addition, the results showed an adverse events (AEs) incidence of 80.5% vs. 88.9% and grade 3–4 treatment-related AEs of 21.4% vs. 36.8% in the nivolumab versus everolimus groups, respectively. Thus, nivolumab shows significant survival and safety advantages over everolimus as a second-line treatment for metastatic ccRCC [109].

- ○

- Pembrolizumab has shown promise as a first-line treatment in various types of cancer. Pembrolizumab was evaluated as a monotherapy for treating naive patients with metastatic ccRCC in a phase II KEYNOTE-427 clinical trial. In this clinical trial, 110 patients received 200 mg of pembrolizumab intravenously every 3 weeks for 24 months. The results showed a median duration of response of 18.9 months (range; 2–37 months) and a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 7.1 months (95% CI; 5–11 months). The 12-month OS and 24-month OS rates were 88.2% vs. 70.8%, respectively. And, 30% of the patients showed grade 3–5 treatment-related AEs, with colitis (5.5%) and diarrhea (3.6%) as the most common AEs [112].

- ■

- PD-L1 inhibitor

- ○

- Atezolizumab was evaluated as a first-line treatment for mRCC in the phase II IMmotion150 clinical trial (NCT01984242) [114]. In this clinical trial, one group of patients received 1200 mg of atezolizumab intravenously once every 3 weeks and the other group of patients received 50 mg of sunitinib every day for 4 weeks. The results showed a PFS of 7.8 months vs. 5.5 months, an overall ORR of 25% vs. 29% in the atezolizumab versus sunitinib groups, respectively. Although the overall ORR in the atezolizumab group was lower, the proportion of patients with complete response in the atezolizumab group was higher [114]. In addition, the incidence of treatment-related AEs in the atezolizumab group was less than that in the sunitinib group.

- ◆

- Application of ICIs combination therapy in ccRCC (Table 3)

- ■

- ipilimumab + nivolumab

- ■

- Emerging + Traditional immune checkpoint inhibitors

- ■

- ICIs combination with anti-VEGF therapy

- ○

- The phase III JAVELIN Renal 101 (NCT02684006) clinical trial evaluated avelumab (a PD-L1 inhibitor) + axitinib combination therapy compared to sunitinib therapy alone and was the first clinical trial to report on ICI + anti-VEGF combination therapy for RCC [113]. In this clinical trial, one group of 442 PD-L1+ RCC patients received avelumab + axitinib combination therapy and the other group of 444 PD-L1+ RCC patients received sunitinib therapy. The results showed an ORR of 55.2% vs. 25.5% and a PFS of 13.8 months vs. 8.4 months in the avelumab + axitinib combination therapy group versus the sunitinib therapy group, respectively. The follow-up results (August 2020) showed a PFS of 13.8 months vs. 7.0 months in the avelumab + axitinib combination therapy group versus the sunitinib therapy group, respectively [126,127]. Based upon this clinical trial, avelumab + axitinib combination therapy achieves short-term positive clinical benefits. The OS rate in this clinical trial is currently too early to calculate.

- ○

- The phase III KEYNOTE-426 (NCT02853331) clinical trial evaluated pembrolizumab + axitinib combination therapy compared to sunitinib therapy alone. In this clinical trial of 861 ccRCC patients, one group of patients received pembrolizumab + axitinib combination therapy and the other group of patients received sunitinib therapy. The results showed a PFS of 15.1 months vs. 11.1 months and an ORR of 59.3% vs. 35.7% in the pembrolizumab + axitinib combination therapy group versus the sunitinib therapy group, respectively. The 30.6-month follow-up results (October 2020) showed an OS of not reached (NR) vs. 35.7 months and a PFS of 15.4 months vs. 11.1 months in the pembrolizumab + axitinib combination therapy group versus the sunitinib therapy group, respectively [128]. Moreover, the extended follow-up results showed an OS of 57.7% vs. 48.5%, a PFS of 25.1% vs. 10.6%, and an ORR of 60.4% vs. 39.6% in the pembrolizumab + axitinib combination therapy group versus the sunitinib therapy group, respectively [129]. The FDA approved pembrolizumab + axitinib combination therapy as a first-line treatment of advanced ccRCC based upon the above-mentioned results.

- ○

- The phase III KEYNOTE-581 (NCT02811861) clinical trial evaluated pembrolizumab + lenvatinib combination therapy compared to sunitinib therapy alone [59,130]. In this clinical trial, one group of 335 advanced ccRCC patients received pembrolizumab + lenvatinib combination therapy and the other group of 357 advanced ccRCC patients received sunitinib therapy alone. The results showed a PFS of 23.9 months vs. 9.2 months and an OS of (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49 to 0.88; p = 0.005) in the pembrolizumab + lenvatinib combination therapy group versus sunitinib therapy group, respectively. The above-mentioned results suggest that pembrolizumab + lenvatinib combination therapy as a first-line treatment of advanced ccRCC patients is superior to sunitinib therapy alone. However, the incidence of treatment-related Grade 3 or higher AEs (e.g., hypertension, diarrhea, and elevated lipase levels) was 82.4% vs. 71.8% in the pembrolizumab + lenvatinib combination therapy group versus the sunitinib therapy group, respectively.

- ○

- The phase III CheckMate 9ER clinical trial evaluated nivolumab + cabozantinib combination therapy compared to sunitinib therapy alone. In this clinical trial, one group of 323 advanced RCC patients received nivolumab + cabozantinib combination therapy and the other group of 328 advanced RCC patients received sunitinib therapy alone. The results showed a PFS of 16.6 months vs. 8.3 months, an OS of 85.7% vs. 75.6%, and an ORR of 55.7% vs. 27.1% in the nivolumab + cabozantinib combination therapy group versus the sunitinib therapy group, respectively. However, the incidence of treatment-related Grade 3 or higher AEs was 82.4% vs. 71.8% in the nivolumab + cabozantinib combination therapy group versus the sunitinib therapy group, respectively. In the nivolumab + cabozantinib combination therapy group, the AEs forced 19.7% of the patients to discontinue use of at least one of the trial drugs and 5.6% of the patients to discontinue use of both trial drugs. Overall, the advanced RCC patients in the nivolumab + cabozantinib combination therapy group had a better quality of life than the patients in the sunitinib therapy group [131].

- ○

- The phase III IMmotion151 (NCT02420821) clinical trial evaluated atezolizumab + bevacizumab combination therapy compared to sunitinib therapy alone [132]. In this clinical trial, one group of 454 RCC patients (about 40% were PD-L1+) received atezolizumab + bevacizumab combination therapy and the other group of 461 RCC patients received sunitinib therapy alone. The results showed a PFS of 11.2 months vs. 7.7 months in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab combination therapy group versus the sunitinib therapy group, respectively. However, the incidence of treatment-related Grade 3–4 AEs was 40% vs. 54% and treatment-related all Grade AEs was 5% vs. 8% in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab combination therapy group versus the sunitinib therapy group, respectively.

- ■

- ICIs combination with cytokine therapy

- ○

- The use of high dose IL-2 in the treatment of advanced ccRCC has been limited due to the severe toxicity of IL-2 [133]. However, in the era of ICIs, the use of IL-2 has been reconsidered. In order to reduce IL-2 toxicity and to improve IL-2 anti-tumor activity, nemvaleukin alfa (nemvaleukin; ALKS 4230) was constructed. Nemvaleukin alfa is a fusion protein of circularly permuted IL-2 to the extracellular domain of IL-2 receptor α (IL-2Rα). Nemvaleukin alfa mimics an intermediate-affinity rather than a high-affinity IL-2R which results in an IL-2 fusion protein that preferentially stimulates effector T cells rather than Tregs cells [134]. The phase I/II ARTISTRY-1 (NCT02799095) clinical trial evaluated pembrolizumab + nemvaleukin alfa combination therapy as a second-line treatment for solid tumors (including RCC). The preliminary results showed an ORR of 16.1% and a disease control rate of 59.9% in a solid tumor cohort [135].

- ○

- Bempegaldesleukin (NKTR-214) is a pegylated form of the cytokine IL-2 which preferentially binds to IL-2Rβ over IL-2Rα. The phase I PIVOT-02 (NCT02983045) clinical trial evaluated nivolumab + NKTR-214 combination therapy as a first-line treatment in 14 advanced RCC patients and as a second-line treatment in 8 patients. The results showed an ORR of 71.4% (first-line treatment) and 28.6% (second-line treatment). However, the incidence of treatment-related Grade 3–4 AEs was 21.1% in the patients. A Phase III randomized clinical trial (PIVOT-09, NCT03729245) investigated the efficacy of bempegaldesleukin in combination with nivolumab compared to sunitinib or cabozantinib in patients with previously untreated advanced ccRCC. The findings indicated an ORR of 23.0% for the combination therapy versus 30.6% for the TKI treatments, with a median OS of 29.0 months. Notably, the adverse reactions associated with the combination of bempegaldesleukin and nivolumab were predominantly pyrexia (32.6% compared to 2.0%) and pruritus (31.3% compared to 8.8%). Furthermore, the incidence of grade 3/4 TRAEs was lower in the group receiving bempegaldesleukin plus nivolumab (25.8%) compared to those receiving TKI therapy (56.5%) [136].

- ○

- Pegilodecakin is a pegylated recombinant human IL-10. The phase 1/1b IVY (NCT02009449) clinical trial evaluated pembrolizumab + pegilodecakin combination therapy compared to nivolumab + pegilodecakin combination therapy against several solid tumors [137]. In this clinical trial, one group of 53 patients received pembrolizumab + pegilodecakin combination therapy and the other group of 58 patients received nivolumab + pegilodecakin combination therapy. The results showed that 93% of patients (103 out of 111) had at least one treatment-related AE and 66% of patients had Grade 3–4 AEs. In a clinical trial involving 38 patients with advanced RCC, the ORR was found to be 40% among the 35 patients who were assessed for response, and 44% among the 27 patients who had received prior treatment [137].

| Clinical Trials | Identifiers | Patients | Arms | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDR0000285624 (II) [108] | NCT00053729 | 61 | Ipilimumab | low dose ORR: 4.8% high dose ORR: 12.5% |

| CheckMate 025 (III) [109,110] | NCT01668784 | 803 | Nivolumab vs. Everolimus | ORR: 23% vs. 4% OS: 25.8 mo vs. 19.7 mo |

| KEYNOTE- 427 (II) [112] | NCT02853344 | 110 | Pembrolizumab | ORR:36.4% PFS:7.1 mo |

| IMmotion 150 (II) [114] | NCT01984242 | 305 | Atezolizumab vs. Sunitinib | ORR:25% vs. 29% PFS:7.8 mo vs. 5.5 mo |

| CheckMate-214 (III) [122,124] | NCT02231749 | 1096 | Nivolumab + Ipilimumab vs. Sunitinib | ORR: 42% vs. 27% PFS: 11.6 mo vs. 8.4 mo OS: NR vs. 26.0 mo |

| JAVELIN Renal 101 (III) [113,127] | NCT02684006 | 886 | Avelumab + Axitinib vs. Sunitinib | ORR: 55.2% vs. 25.5% PFS: 13.8 mo vs. 8.4 mo OS: 10.8 mo vs. 8.6 mo |

| KEYNOTE-426 (III) [128,139] | NCT02853331 | 861 | Pembrolizumab + Axitinib vs. Sunitinib | ORR: 59.3% vs. 35.7% PFS: 15.1 mo vs. 11.1 mo |

| CheckMate 9ER (III) [131] | NCT03141177 | 651 | Nivolumab + Cabozantinib vs. Sunitinib | ORR: 55.7% vs. 27.1% PFS: 16.6 mo vs. 8.3 mo |

| KEYNOTE-581 (III) [59] | NCT02811861 | 1069 | Pembrolizumab + Lenvatinib vs. Sunitinib | ORR: 71% vs. 36.1% PFS: 23.9 mo vs. 9.2 mo |

| IMmotion 151 (III) [132] | NCT02420821 | 915 | Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab vs. Sunitinib | PD-L1+ patients ORR: 43% vs. 35% PFS: 11.2 mo vs. 7.7 mo ITT population ORR: 37% vs. 33% PFS: 11.2 mo vs. 8.4 mo |

| ALKS 4230 (I/II) [134,135] | NCT02799095 | 243 | Pembrolizumab + Nemvaleukin alfa vs. Nemvaleukin alfa | ORR: 16.1% (combination) ORR:18.2% (monotherapy) |

| PIVOT-02 (I) [140] | NCT02983045 | 22 | Nivolumab + NKTR-214 (1st line and 2nd line) | ORR: 71.4 (1st line) % and 28.6% (2nd line) |

| IVY(I) [137,138] | NCT02009449 | 62 | Pembrolizumab/Nivolumab + Pegilodecakin vs. pegilodecakin | ORR: 43% vs. 20% PFS: 13.9 mo vs. 1.8 mo |

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padala, S.A.; Barsouk, A.; Thandra, K.C.; Saginala, K.; Mohammed, A.; Vakiti, A.; Rawla, P.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of Renal Cell Carcinoma. World J. Oncol. 2020, 11, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escudier, B.; Porta, C.; Schmidinger, M.; Rioux-Leclercq, N.; Bex, A.; Khoo, V.; Grünwald, V.; Gillessen, S.; Horwich, A. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Mooi, J.; Lawrentschuk, N.; McKay, R.R.; Hannan, R.; Lo, S.S.; Hall, W.A.; Siva, S. The Role of Stereotactic Ablative Body Radiotherapy in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2022, 82, 613–622, Erratum in Eur. Urol. 2022, 8, e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Correa, R.J.M.; Pryor, D.; Higgs, B.; Sridharan, S.; Sidhom, M.; Muacevic, A.; Onishi, H.; Swaminath, A.; Grubb, W.; et al. Efficacy of SABR in Uncommon Subtypes of Primary Kidney Cancer: An Analysis From the International Radiosurgery Oncology Consortium of the Kidney. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2025. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wong, Y.-N.; Armstrong, K.; Haas, N.; Subedi, P.; Davis-Cerone, M.; Doshi, J.A. Survival among patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma in the pretargeted versus targeted therapy eras. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, D.F.; Regan, M.M.; Clark, J.I.; Flaherty, L.E.; Weiss, G.R.; Logan, T.F.; Kirkwood, J.M.; Gordon, M.S.; Sosman, J.A.; Ernstoff, M.S.; et al. Randomized phase III trial of high-dose interleukin-2 versus subcutaneous interleukin-2 and interferon in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudier, B.; Eisen, T.; Stadler, W.M.; Szczylik, C.; Oudard, S.; Siebels, M.; Negrier, S.; Chevreau, C.; Solska, E.; Desai, A.A.; et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 125–134, Erratum in N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, B.; Truong, L.D. Renal epithelial neoplasms: The diagnostic implications of electron microscopic study in 55 cases. Hum. Pathol. 2002, 33, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezami, B.G.; MacLennan, G.T. Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review of its Histopathology, Genetics, and Differential Diagnosis. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2025, 33, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickerson, M.L.; Jaeger, E.; Shi, Y.; Durocher, J.A.; Mahurkar, S.; Zaridze, D.; Matveev, V.; Janout, V.; Kollarova, H.; Bencko, V.; et al. Improved identification of von Hippel-Lindau gene alterations in clear cell renal tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 4726–4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Yoshizato, T.; Shiraishi, Y.; Maekawa, S.; Okuno, Y.; Kamura, T.; Shimamura, T.; Sato-Otsubo, A.; Nagae, G.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Integrated molecular analysis of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugarolas, J. Molecular genetics of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1968–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Tan, P.; Ishihara, M.; Bayley, N.A.; Schokrpur, S.; Reynoso, J.G.; Zhang, Y.; Lim, R.J.; Dumitras, C.; Yang, L.; et al. Tumor heterogeneity in VHL drives metastasis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S.; Higgins, P.J.; Samarakoon, R. Downstream Targets of VHL/HIF-α Signaling in Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma Progression: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Relevance. Cancers 2023, 15, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, P.E. The role of VHL in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma and its relation to targeted therapy. Kidney Int. 2009, 76, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; German, P.; Bai, S.; Barnes, S.; Guo, W.; Qi, X.; Lou, H.; Liang, J.; Jonasch, E.; Mills, G.B.; et al. The PI3K/AKT Pathway and Renal Cell Carcinoma. J. Genet. Genom. 2015, 42, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cai, W.; Cai, B.; Kong, W.; Zhai, W.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Bai, Y.; Huang, Y.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Landscape in Chinese Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 697219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, C.; Machaalani, M.; Bonventre, J.V.; McDermott, D.F.; Choueiri, T.K.; Xu, W. KIM-1 as a Prognostic Marker in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. Focus. 2025, 11, 432–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachostergios, P.J.; Karathanasis, A.; Karasavvidou, F.; Tzortzis, V. Association of KIM-1 (HAVCR1) Expression with the Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Curr. Gene Ther. 2025, 26, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borcherding, N.; Vishwakarma, A.; Voigt, A.P.; Bellizzi, A.; Kaplan, J.; Nepple, K.; Salem, A.K.; Jenkins, R.W.; Zakharia, Y.; Zhang, W. Mapping the immune environment in clear cell renal carcinoma by single-cell genomics. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-C.; Jin, Z.; Kolb, R.; Borcherding, N.; Chatzkel, J.A.; Falzarano, S.M.; Zhang, W. Updates on Immunotherapy and Immune Landscape in Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevrier, S.; Levine, J.H.; Zanotelli, V.R.T.; Silina, K.; Schulz, D.; Bacac, M.; Ries, C.H.; Ailles, L.; Jewett, M.A.S.; Moch, H.; et al. An Immune Atlas of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cell 2017, 169, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annels, N.E.; Denyer, M.; Nicol, D.; Hazell, S.; Silvanto, A.; Crockett, M.; Hussain, M.; Moller-Levet, C.; Pandha, H. The dysfunctional immune response in renal cell carcinoma correlates with changes in the metabolic landscape of ccRCC during disease progression. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 4221–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Akbarinejad, S.; Shahriyari, L. Immune classification of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kippenberger, M.; Schönberg, G.; Kaczorowski, A.; Schneider, F.; Böning, S.; Sun, A.; Schwab, C.; Görtz, M.; Schütz, V.; Stenzinger, A.; et al. Immune landscape of renal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the pancreas. Urol. Oncol. 2024, 42, e9–e373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.M.; Madden, M.Z.; Arner, E.N.; Bader, J.E.; Ye, X.; Vlach, L.; Tigue, M.L.; Landis, M.D.; Jonker, P.B.; Hatem, Z.; et al. VHL loss reprograms the immune landscape to promote an inflammatory myeloid microenvironment in renal tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e173934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhao, J.; Luo, X.; Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Q.; Lu, H.; Meng, Y.; Cai, K.; Lu, L.; et al. Transcriptome Profiling Reveals B-Lineage Cells Contribute to the Poor Prognosis and Metastasis of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 731896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Liu, Z.; Cai, C.; Duan, X.; Deng, T.; Zeng, G. m6A modification patterns and tumor immune landscape in clear cell renal carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e001646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.M.; Adnane, L.; Newell, P.; Villanueva, A.; Llovet, J.M.; Lynch, M. Preclinical overview of sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets both Raf and VEGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 3129–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röllig, C.; Serve, H.; Noppeney, R.; Hanoun, M.; Krug, U.; Baldus, C.D.; Brandts, C.H.; Kunzmann, V.; Einsele, H.; Krämer, A.; et al. Sorafenib or placebo in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukaemia: Long-term follow-up of the randomized controlled SORAML trial. Leukemia 2021, 35, 2517–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brose, M.S.; Nutting, C.M.; Jarzab, B.; Elisei, R.; Siena, S.; Bastholt, L.; de la Fouchardiere, C.; Pacini, F.; Paschke, R.; Shong, Y.K.; et al. Sorafenib in radioactive iodine-refractory, locally advanced or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer: A randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2014, 384, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, T.J.; Lee, L.B.; Murray, L.J.; Pryer, N.K.; Cherrington, J.M. SU11248 inhibits KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta in preclinical models of human small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003, 2, 471–478. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, T.J.; Murray, L.J.; Pesenti, E.; Holway, V.W.; Colombo, T.; Lee, L.B.; Cherrington, J.M.; Pryer, N.K. Preclinical evaluation of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor SU11248 as a single agent and in combination with "standard of care" therapeutic agents for the treatment of breast cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003, 2, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Faivre, S.; Demetri, G.; Sargent, W.; Raymond, E. Molecular basis for sunitinib efficacy and future clinical development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Luo, W.-M.; Zhang, Z.-F.; Snider, J.; Vandenbeldt, K.; Qian, C.-N.; Teh, B.T. Sunitinib acts primarily on tumor endothelium rather than tumor cells to inhibit the growth of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 1053–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.T.J.; Jones, R.L.; Huang, P.H. Pazopanib in advanced soft tissue sarcomas. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2019, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Vidal, M.J.; Molina, Á.; Anido, U.; Chirivella, I.; Etxaniz, O.; Fernández-Parra, E.; Guix, M.; Hernández, C.; Lambea, J.; Montesa, Á.; et al. Pazopanib: Evidence review and clinical practice in the management of advanced renal cell carcinoma. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 19, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.W.; Lee, S.-M. Axitinib for the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2013, 22, 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiecicki, P.L.; Bellile, E.L.; Brummel, C.V.; Brenner, J.C.; Worden, F.P. Efficacy of axitinib in metastatic head and neck cancer with novel radiographic response criteria. Cancer 2021, 127, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woll, P.J.; Gaunt, P.; Gaskell, C.; Young, R.; Benson, C.; Judson, I.R.; Seddon, B.M.; Marples, M.; Ali, N.; Strauss, S.J.; et al. Axitinib in patients with advanced/metastatic soft tissue sarcoma (Axi-STS): An open-label, multicentre, phase II trial in four histological strata. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 129, 1490–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellesoeur, A.; Carton, E.; Alexandre, J.; Goldwasser, F.; Huillard, O. Axitinib in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma: Design, development, and place in therapy. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2017, 11, 2801–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Meyer, T.; Cheng, A.-L.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Rimassa, L.; Ryoo, B.-Y.; Cicin, I.; Merle, P.; Chen, Y.; Park, J.-W.; et al. Cabozantinib in Patients with Advanced and Progressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M.B.; Tannir, N.M. Current and emerging therapies for first-line treatment of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2018, 70, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Escudier, B.; Powles, T.; Mainwaring, P.N.; Rini, B.I.; Donskov, F.; Hammers, H.; Hutson, T.E.; Lee, J.-L.; Peltola, K.; et al. Cabozantinib versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1814–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Halabi, S.; Sanford, B.L.; Hahn, O.; Michaelson, M.D.; Walsh, M.K.; Feldman, D.R.; Olencki, T.; Picus, J.; Small, E.J.; et al. Cabozantinib Versus Sunitinib As Initial Targeted Therapy for Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma of Poor or Intermediate Risk: The Alliance A031203 CABOSUN Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 591–597, Erratum in J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloughesy, T.F.; Drappatz, J.; de Groot, J.; Prados, M.D.; Reardon, D.A.; Schiff, D.; Chamberlain, M.; Mikkelsen, T.; Desjardins, A.; Ping, J.; et al. Phase II study of cabozantinib in patients with progressive glioblastoma: Subset analysis of patients with prior antiangiogenic therapy. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisei, R.; Schlumberger, M.J.; Müller, S.P.; Schöffski, P.; Brose, M.S.; Shah, M.H.; Licitra, L.; Jarzab, B.; Medvedev, V.; Kreissl, M.C.; et al. Cabozantinib in progressive medullary thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 3639–3646, Erratum in J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroiss, M.; Megerle, F.; Kurlbaum, M.; Zimmermann, S.; Wendler, J.; Jimenez, C.; Lapa, C.; Quinkler, M.; Scherf-Clavel, O.; Habra, M.A.; et al. Objective Response and Prolonged Disease Control of Advanced Adrenocortical Carcinoma with Cabozantinib. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 1461–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöffski, P.; Gordon, M.; Smith, D.C.; Kurzrock, R.; Daud, A.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Lee, Y.; Scheffold, C.; Shapiro, G.I. Phase II randomised discontinuation trial of cabozantinib in patients with advanced solid tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 86, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolaney, S.M.; Nechushtan, H.; Ron, I.-G.; Schöffski, P.; Awada, A.; Yasenchak, C.A.; Laird, A.D.; O’Keeffe, B.; Shapiro, G.I.; Winer, E.P. Cabozantinib for metastatic breast carcinoma: Results of a phase II placebo-controlled randomized discontinuation study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 160, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolaney, S.M.; Ziehr, D.R.; Guo, H.; Ng, M.R.; Barry, W.T.; Higgins, M.J.; Isakoff, S.J.; Brock, J.E.; Ivanova, E.V.; Paweletz, C.P.; et al. Phase II and Biomarker Study of Cabozantinib in Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Patients. Oncologist 2021, 26, e1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, P.Y.; Drappatz, J.; de Groot, J.; Prados, M.D.; Reardon, D.A.; Schiff, D.; Chamberlain, M.; Mikkelsen, T.; Desjardins, A.; Holland, J.; et al. Phase II study of cabozantinib in patients with progressive glioblastoma: Subset analysis of patients naive to antiangiogenic therapy. Neuro Oncol. 2018, 20, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, M.; De Divitiis, C.; Ottaiano, A.; von Arx, C.; Scala, S.; Tatangelo, F.; Delrio, P.; Tafuto, S. Lenvatinib, a molecule with versatile application: From preclinical evidence to future development in anti-cancer treatment. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 3847–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, T.; Watanabe Miyano, S.; Watanabe, H.; Sonobe, R.M.K.; Seki, Y.; Ohta, E.; Nomoto, K.; Matsui, J.; Funahashi, Y. Lenvatinib induces death of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells harboring an activated FGF signaling pathway through inhibition of FGFR-MAPK cascades. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 513, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M.; Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Han, K.-H.; Ikeda, K.; Piscaglia, F.; Baron, A.; Park, J.-W.; Han, G.; Jassem, J.; et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 1163–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuki, M.; Hoshi, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ikemori-Kawada, M.; Minoshima, Y.; Funahashi, Y.; Matsui, J. Lenvatinib inhibits angiogenesis and tumor fibroblast growth factor signaling pathways in human hepatocellular carcinoma models. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 2641–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.; Alekseev, B.; Rha, S.-Y.; Porta, C.; Eto, M.; Powles, T.; Grünwald, V.; Hutson, T.E.; Kopyltsov, E.; Méndez-Vidal, M.J.; et al. Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab or Everolimus for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlumberger, M.; Tahara, M.; Wirth, L.J.; Robinson, B.; Brose, M.S.; Elisei, R.; Habra, M.A.; Newbold, K.; Shah, M.H.; Hoff, A.O.; et al. Lenvatinib versus placebo in radioiodine-refractory thyroid cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, J.; Satouchi, M.; Itoh, S.; Okuma, Y.; Niho, S.; Mizugaki, H.; Murakami, H.; Fujisaka, Y.; Kozuki, T.; Nakamura, K.; et al. Lenvatinib in patients with advanced or metastatic thymic carcinoma (REMORA): A multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, A.; Shook, J.; Hutson, T.E. Tivozanib, a highly potent and selective inhibitor of VEGF receptor tyrosine kinases, for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Future Oncol. 2020, 16, 2147–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, N.; Hillan, K.J.; Gerber, H.-P.; Novotny, W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody for treating cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musella, A.; Vertechy, L.; Romito, A.; Marchetti, C.; Giannini, A.; Sciuga, V.; Bracchi, C.; Tomao, F.; Di Donato, V.; De Felice, F.; et al. Bevacizumab in Ovarian Cancer: State of the Art and Unanswered Questions. Chemotherapy 2017, 62, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, K.S.; Sill, M.W.; Long, H.J.; Penson, R.T.; Huang, H.; Ramondetta, L.M.; Landrum, L.M.; Oaknin, A.; Reid, T.J.; Leitao, M.M.; et al. Improved survival with bevacizumab in advanced cervical cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Zhou, Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Hua, W.; Mao, Y. Use of Bevacizumab in recurrent glioblastoma: A scoping review and evidence map. BMC Cancer 2023, 23, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harshman, L.C.; Srinivas, S. The bevacizumab experience in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2010, 3, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vokes, E.E.; Salgia, R.; Karrison, T.G. Evidence-based role of bevacizumab in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, L.S.; Jacobs, I.A.; Burkes, R.L. Bevacizumab in Colorectal Cancer: Current Role in Treatment and the Potential of Biosimilars. Target. Oncol. 2017, 12, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusceddu, S.; Verzoni, E.; Prinzi, N.; Mennitto, A.; Femia, D.; Grassi, P.; Concas, L.; Vernieri, C.; Lo Russo, G.; Procopio, G. Everolimus treatment for neuroendocrine tumors: Latest results and clinical potential. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2017, 9, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buti, S.; Leonetti, A.; Dallatomasina, A.; Bersanelli, M. Everolimus in the management of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: An evidence-based review of its place in therapy. Core Evid. 2016, 11, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Peng, Z.; Jiang, H.; Ma, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, Q.; Tian, X.; Han, Y.; Ji, D.; et al. Everolimus treatment in patients with hormone receptor-positive and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer and a predictive model for its efficacy: A multicenter real-world study. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2024, 16, 17588359241292256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyling, M.; Jurczak, W.; Jerkeman, M.; Silva, R.S.; Rusconi, C.; Trneny, M.; Offner, F.; Caballero, D.; Joao, C.; Witzens-Harig, M.; et al. Ibrutinib versus temsirolimus in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: An international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2016, 387, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, D.; Curran, M.P. Temsirolimus: In advanced renal cell carcinoma. Drugs 2008, 68, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Du, K.; Liu, Z.; Li, J. Inhibition of mTOR by temsirolimus overcomes radio-resistance in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2022, 49, 703–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, R.M. The immune checkpoint inhibitors: Where are we now? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 883–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yu, J.X.; Hubbard-Lucey, V.M.; Neftelinov, S.T.; Hodge, J.P.; Lin, Y. Trial watch: The clinical trial landscape for PD1/PDL1 immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 854–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgeaud, M.; Sandoval, J.; Obeid, M.; Banna, G.; Michielin, O.; Addeo, A.; Friedlaender, A. Novel targets for immune-checkpoint inhibition in cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2023, 120, 102614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.R.; Wu, X.L.; Sun, Y.L. Therapeutic targets and biomarkers of tumor immunotherapy: Response versus non-response. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Shao, Z.; Wen, X.; Jiang, J.; Ma, Q.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Ding, X.; Zhang, L. TREM2: Keeping Pace With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 716710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Song, Q.; Sun, X.; Xue, M.; Yang, Z.; Shang, J. Comprehensive analysis of CTLA-4 in the tumor immune microenvironment of 33 cancer types. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 85, 106633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentcheva-Hoang, T.; Egen, J.G.; Wojnoonski, K.; Allison, J.P. B7-1 and B7-2 selectively recruit CTLA-4 and CD28 to the immunological synapse. Immunity 2004, 21, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokosuka, T.; Kobayashi, W.; Takamatsu, M.; Sakata-Sogawa, K.; Zeng, H.; Hashimoto-Tane, A.; Yagita, H.; Tokunaga, M.; Saito, T. Spatiotemporal basis of CTLA-4 costimulatory molecule-mediated negative regulation of T cell activation. Immunity 2010, 33, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussiotis, V.A. Molecular and Biochemical Aspects of the PD-1 Checkpoint Pathway. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, D.L.; Wherry, E.J.; Masopust, D.; Zhu, B.; Allison, J.P.; Sharpe, A.H.; Freeman, G.J.; Ahmed, R. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 2006, 439, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsoukis, N.; Brown, J.; Petkova, V.; Liu, F.; Li, L.; Boussiotis, V.A. Selective effects of PD-1 on Akt and Ras pathways regulate molecular components of the cell cycle and inhibit T cell proliferation. Sci. Signal 2012, 5, ra46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, F.; Chen, M.; Gao, Z.; Hu, L.; Xuan, J.; Li, X.; Song, Z.; et al. PD1/PD-L1 blockade in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Mechanistic insights, clinical efficacy, and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yin, X.; Zhang, H.; Sun, G.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, P.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; et al. Differential expressions of PD-1, PD-L1 and PD-L2 between primary and metastatic sites in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffo, E.; Wu, R.C.; Bruno, T.C.; Workman, C.J.; Vignali, D.A.A. Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3): The next immune checkpoint receptor. Semin. Immunol. 2019, 42, 101305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, M.V.; Drake, C.G. LAG-3 in Cancer Immunotherapy. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2011, 344, 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, Q.; Antfolk, D.; Price, D.A.; Manturova, A.; Medina, E.; Singh, S.; Mason, C.; Tran, T.H.; Smalley, K.S.M.; Leung, D.W.; et al. Structural basis for mouse LAG3 interactions with the MHC class II molecule I-Ab. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.-R.; Turnis, M.E.; Goldberg, M.V.; Bankoti, J.; Selby, M.; Nirschl, C.J.; Bettini, M.L.; Gravano, D.M.; Vogel, P.; Liu, C.L.; et al. Immune inhibitory molecules LAG-3 and PD-1 synergistically regulate T-cell function to promote tumoral immune escape. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelba, H.; Bedke, J.; Hennenlotter, J.; Mostböck, S.; Zettl, M.; Zichner, T.; Chandran, A.; Stenzl, A.; Rammensee, H.-G.; Gouttefangeas, C. PD-1 and LAG-3 Dominate Checkpoint Receptor-Mediated T-cell Inhibition in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2019, 7, 1891–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, J.-M.; Zarour, H.M. TIGIT in cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjunpää, H.; Guillerey, C. TIGIT as an emerging immune checkpoint. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2020, 200, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X. Correlation of T Cell Immunoglobulin and ITIM Domain (TIGIT) and Programmed Death 1 (PD-1) with Clinicopathological Characteristics of Renal Cell Carcinoma May Indicate Potential Targets for Treatment. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 6861–6872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Zhu, C.; Kuchroo, V.K. Tim-3 and its role in regulating anti-tumor immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 276, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wherry, E.J.; Kurachi, M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuishi, K.; Apetoh, L.; Sullivan, J.M.; Blazar, B.R.; Kuchroo, V.K.; Anderson, A.C. Targeting Tim-3 and PD-1 pathways to reverse T cell exhaustion and restore anti-tumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 2187–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granier, C.; Dariane, C.; Combe, P.; Verkarre, V.; Urien, S.; Badoual, C.; Roussel, H.; Mandavit, M.; Ravel, P.; Sibony, M.; et al. Tim-3 Expression on Tumor-Infiltrating PD-1+CD8+ T Cells Correlates with Poor Clinical Outcome in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, J.L.; Pantazi, E.; Mak, J.; Sempere, L.F.; Wang, L.; O’Connell, S.; Ceeraz, S.; Suriawinata, A.A.; Yan, S.; Ernstoff, M.S.; et al. VISTA is an immune checkpoint molecule for human T cells. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1924–1932, Erratum in Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.S.; Molloy, M.; Ugolkov, A.; von Roemeling, R.W.; Noelle, R.J.; Lewis, L.D.; Johnson, M.; Radvanyi, L.; Martell, R.E. VISTA expression and patient selection for immune-based anticancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1086102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, W.; Putra, J.; Suriawinata, A.A.; Schenk, A.D.; Miller, H.E.; Guleria, I.; Barth, R.J.; Huang, Y.H.; et al. Immune-checkpoint proteins VISTA and PD-1 nonredundantly regulate murine T-cell responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 6682–6687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Yuan, Q.; Xia, H.; Zhu, G.; Feng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; He, W.; Lu, J.; Dong, C.; et al. Analysis of VISTA expression and function in renal cell carcinoma highlights VISTA as a potential target for immunotherapy. Protein Cell 2019, 10, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronik-Le Roux, D.; Sautreuil, M.; Bentriou, M.; Vérine, J.; Palma, M.B.; Daouya, M.; Bouhidel, F.; Lemler, S.; LeMaoult, J.; Desgrandchamps, F.; et al. Comprehensive landscape of immune-checkpoints uncovered in clear cell renal cell carcinoma reveals new and emerging therapeutic targets. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 1237–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Ladomersky, E.; Lenzen, A.; Nguyen, B.; Patel, R.; Lauing, K.L.; Wu, M.; Wainwright, D.A. IDO1 in cancer: A Gemini of immune checkpoints. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2018, 15, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireson, A.; Devos, M.; Brochez, L. IDO Expression in Cancer: Different Compartment, Different Functionality? Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 531491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.C.; Hughes, M.; Kammula, U.; Royal, R.; Sherry, R.M.; Topalian, S.L.; Suri, K.B.; Levy, C.; Allen, T.; Mavroukakis, S.; et al. Ipilimumab (anti-CTLA4 antibody) causes regression of metastatic renal cell cancer associated with enteritis and hypophysitis. J. Immunother. 2007, 30, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornstein, M.C.; Wood, L.S.; Hobbs, B.P.; Allman, K.D.; Martin, A.; Bevan, M.; Gilligan, T.D.; Garcia, J.A.; Rini, B.I. A phase II trial of intermittent nivolumab in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) who have received prior anti-angiogenic therapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; George, S.; Hammers, H.J.; Srinivas, S.; Tykodi, S.S.; Sosman, J.A.; Plimack, E.R.; Procopio, G.; McDermott, D.F.; et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: Updated results with long-term follow-up of the randomized, open-label, phase 3 CheckMate 025 trial. Cancer 2020, 126, 4156–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; George, S.; Hammers, H.J.; Srinivas, S.; Tykodi, S.S.; Sosman, J.A.; Procopio, G.; Plimack, E.R.; et al. Nivolumab versus Everolimus in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, D.F.; Lee, J.-L.; Bjarnason, G.A.; Larkin, J.M.G.; Gafanov, R.A.; Kochenderfer, M.D.; Jensen, N.V.; Donskov, F.; Malik, J.; Poprach, A.; et al. Open-Label, Single-Arm Phase II Study of Pembrolizumab Monotherapy as First-Line Therapy in Patients With Advanced Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1020–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Penkov, K.; Haanen, J.; Rini, B.; Albiges, L.; Campbell, M.T.; Venugopal, B.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Negrier, S.; Uemura, M.; et al. Avelumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, D.F.; Huseni, M.A.; Atkins, M.B.; Motzer, R.J.; Rini, B.I.; Escudier, B.; Fong, L.; Joseph, R.W.; Pal, S.K.; Reeves, J.A.; et al. Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 749–757, Erratum in Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Rini, B.I.; Beckermann, K.E. Emerging Targets in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes de Morais, A.L.; Cerdá, S.; de Miguel, M. New Checkpoint Inhibitors on the Road: Targeting TIM-3 in Solid Tumors. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2022, 24, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curigliano, G.; Gelderblom, H.; Mach, N.; Doi, T.; Tai, D.; Forde, P.M.; Sarantopoulos, J.; Bedard, P.L.; Lin, C.-C.; Hodi, F.S.; et al. Phase I/Ib Clinical Trial of Sabatolimab, an Anti-TIM-3 Antibody, Alone and in Combination with Spartalizumab, an Anti-PD-1 Antibody, in Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 3620–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, D.; Paliwal, S.; Dharmadhikari, B.; Guan, S.; Liu, L.; Kar, S.; Tulsian, N.K.; Gruber, J.J.; DiMascio, L.; Paszkiewicz, K.H.; et al. Rationally targeted anti-VISTA antibody that blockades the C-C’ loop region can reverse VISTA immune suppression and remodel the immune microenvironment to potently inhibit tumor growth in an Fc independent manner. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003382, Erratum in J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003382corr1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadonato, S.; Ovechkina, Y.; Lustig, K.; Cross, J.; Eyde, N.; Frazier, E.; Kabi, N.; Katz, C.; Lance, R.; Peckham, D.; et al. A highly potent anti-VISTA antibody KVA12123—A new immune checkpoint inhibitor and a promising therapy against poorly immunogenic tumors. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1311658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, P.N.; Villanueva, L.; Ibanez, C.; Erman, M.; Lee, J.L.; Heinrich, D.; Lipatov, O.N.; Gedye, C.; Gokmen, E.; Acevedo, A.; et al. A randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial of pembrolizumab plus epacadostat versus sunitinib or pazopanib as first-line treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-679/ECHO-302). BMC Cancer 2024, 23, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.H.; LoRusso, P.; Burris, H.; Gordon, M.; Bang, Y.-J.; Hellmann, M.D.; Cervantes, A.; Ochoa de Olza, M.; Marabelle, A.; Hodi, F.S.; et al. Phase I Study of the Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) Inhibitor Navoximod (GDC-0919) Administered with PD-L1 Inhibitor (Atezolizumab) in Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 3220–3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motzer, R.J.; Tannir, N.M.; McDermott, D.F.; Arén Frontera, O.; Melichar, B.; Choueiri, T.K.; Plimack, E.R.; Barthélémy, P.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, M.B.; Jegede, O.A.; Haas, N.B.; McDermott, D.F.; Bilen, M.A.; Stein, M.; Sosman, J.A.; Alter, R.; Plimack, E.R.; Ornstein, M.; et al. Phase II Study of Nivolumab and Salvage Nivolumab/Ipilimumab in Treatment-Naive Patients With Advanced Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (HCRN GU16-260-Cohort A). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2913–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albiges, L.; Tannir, N.M.; Burotto, M.; McDermott, D.; Plimack, E.R.; Barthélémy, P.; Porta, C.; Powles, T.; Donskov, F.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: Extended 4-year follow-up of the phase III CheckMate 214 trial. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e001079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannir, N.M.; Albigès, L.; McDermott, D.F.; Burotto, M.; Choueiri, T.K.; Hammers, H.J.; Barthélémy, P.; Plimack, E.R.; Porta, C.; George, S.; et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: Extended 8-year follow-up results of efficacy and safety from the phase III CheckMate 214 trial. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 1026–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haanen, J.B.A.G.; Larkin, J.; Choueiri, T.K.; Albiges, L.; Rini, B.I.; Atkins, M.B.; Schmidinger, M.; Penkov, K.; Michelon, E.; Wang, J.; et al. Extended follow-up from JAVELIN Renal 101: Subgroup analysis of avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib by the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium risk group in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. ESMO Open 2023, 8, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Motzer, R.J.; Rini, B.I.; Haanen, J.; Campbell, M.T.; Venugopal, B.; Kollmannsberger, C.; Gravis-Mescam, G.; Uemura, M.; Lee, J.L.; et al. Updated efficacy results from the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial: First-line avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powles, T.; Plimack, E.R.; Soulières, D.; Waddell, T.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Melichar, B.; Vynnychenko, I.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib monotherapy as first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-426): Extended follow-up from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1563–1573, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimack, E.R.; Powles, T.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Nosov, D.; Waddell, T.; Alekseev, B.; Pouliot, F.; Melichar, B.; Soulières, D.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Axitinib Versus Sunitinib as First-line Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: 43-month Follow-up of the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-426 Study. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 449–454, Erratum in Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, e123–e124; Erratum in Eur. Urol. 2024, 85, e58–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motzer, R.J.; Porta, C.; Eto, M.; Powles, T.; Grünwald, V.; Hutson, T.E.; Alekseev, B.; Rha, S.Y.; Merchan, J.; Goh, J.C.; et al. Lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab Versus Sunitinib in First-Line Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: Final Prespecified Overall Survival Analysis of CLEAR, a Phase III Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Powles, T.; Burotto, M.; Escudier, B.; Bourlon, M.T.; Zurawski, B.; Oyervides Juárez, V.M.; Hsieh, J.J.; Basso, U.; Shah, A.Y.; et al. Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rini, B.I.; Powles, T.; Atkins, M.B.; Escudier, B.; McDermott, D.F.; Suarez, C.; Bracarda, S.; Stadler, W.M.; Donskov, F.; Lee, J.L.; et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib in patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma (IMmotion151): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 2404–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fyfe, G.; Fisher, R.I.; Rosenberg, S.A.; Sznol, M.; Parkinson, D.R.; Louie, A.C. Results of treatment of 255 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma who received high-dose recombinant interleukin-2 therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 1995, 13, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, J.E.; Fisher, J.L.; Flick, H.L.; Wang, C.; Sun, L.; Ernstoff, M.S.; Alvarez, J.C.; Losey, H.C. ALKS 4230: A novel engineered IL-2 fusion protein with an improved cellular selectivity profile for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8, e000673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishampayan, U.N.; Muzaffar, J.; Winer, I.; Rosen, S.D.; Hoimes, C.J.; Chauhan, A.; Spreafico, A.; Lewis, K.D.; Bruno, D.S.; Dumas, O.; et al. Nemvaleukin alfa, a modified interleukin-2 cytokine, as monotherapy and with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced solid tumors (ARTISTRY-1). J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e010143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannir, N.M.; Formiga, M.N.; Penkov, K.; Kislov, N.; Vasiliev, A.; Gunnar Skare, N.; Hong, W.; Dai, S.; Tang, L.; Qureshi, A.; et al. Bempegaldesleukin Plus Nivolumab Versus Sunitinib or Cabozantinib in Previously Untreated Advanced Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Phase III Randomized Study (PIVOT-09). J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 2800–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, A.; Wong, D.J.; Infante, J.R.; Korn, W.M.; Aljumaily, R.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Autio, K.A.; Pant, S.; Bauer, T.M.; Drakaki, A.; et al. Pegilodecakin combined with pembrolizumab or nivolumab for patients with advanced solid tumours (IVY): A multicentre, multicohort, open-label, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 1544–1555, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannir, N.M.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Wong, D.J.; Aljumaily, R.; Hung, A.; Afable, M.; Kim, J.S.; Ferry, D.; Drakaki, A.; Bendell, J.; et al. Pegilodecakin as monotherapy or in combination with anti-PD-1 or tyrosine kinase inhibitor in heavily pretreated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: Final results of cohorts A, G, H and I of IVY Phase I study. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulières, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, A.; Tannir, N.M.; Bentebibel, S.-E.; Hwu, P.; Papadimitrakopoulou, V.; Haymaker, C.; Kluger, H.M.; Gettinger, S.N.; Sznol, M.; Tykodi, S.S.; et al. Bempegaldesleukin (NKTR-214) plus Nivolumab in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors: Phase I Dose-Escalation Study of Safety, Efficacy, and Immune Activation (PIVOT-02). Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 1158–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

An, Y.; Luo, N. Immune Landscape and Application of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411986

An Y, Luo N. Immune Landscape and Application of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411986

Chicago/Turabian StyleAn, Yanhe, and Na Luo. 2025. "Immune Landscape and Application of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411986

APA StyleAn, Y., & Luo, N. (2025). Immune Landscape and Application of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411986