When Mitochondria Falter, the Barrier Fails: Mechanisms of Inner Blood-Retinal Barrier (iBRB) Injury and Opportunities for Mitochondria-Targeted Repair

Abstract

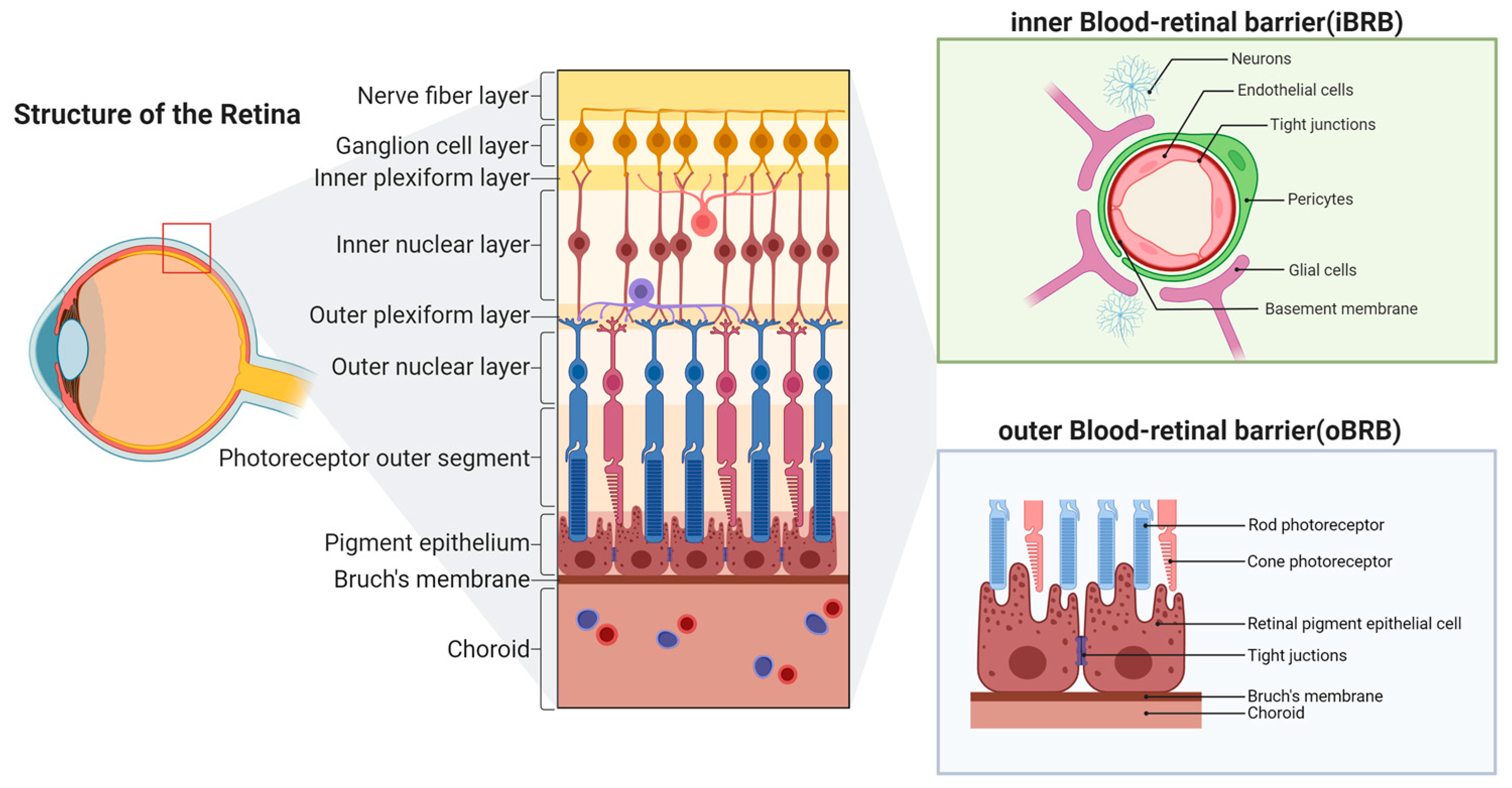

1. Introduction

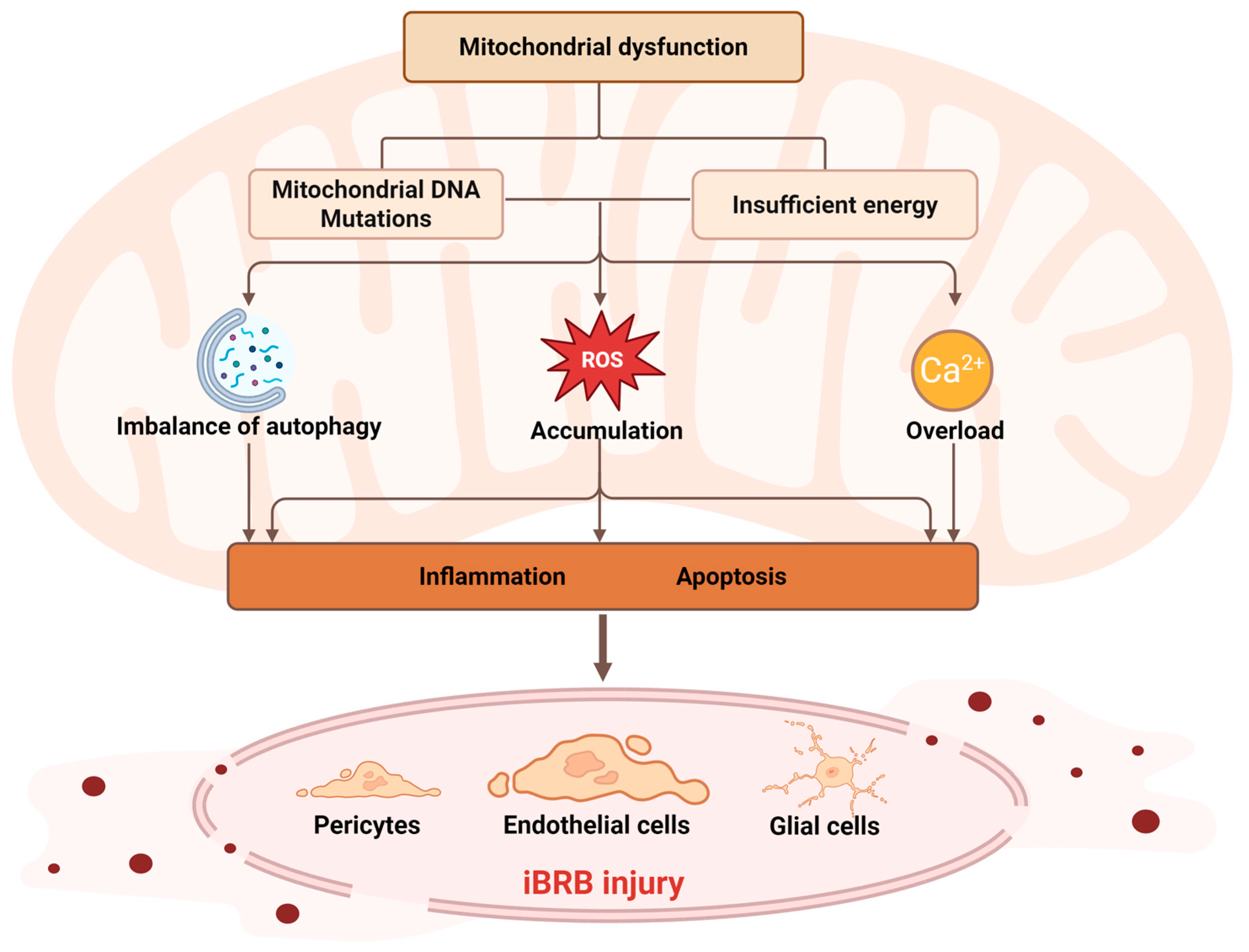

2. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Its Molecular Mechanisms

2.1. Mitochondrial DNA Mutations

2.2. Cellular Energy Supply and Metabolic Disorders

2.3. ROS Generation and Oxidative Stress

2.4. Regulation of Mitophagy

2.5. Regulation and Dysregulation of Calcium Homeostasis

2.6. Mitochondrial Dynamics Balance (Fusion and Fission)

3. Mechanisms of iBRB Damage Induced by Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Retinal Diseases

3.1. Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)

3.2. Retinal Vein Occlusion (RVO)

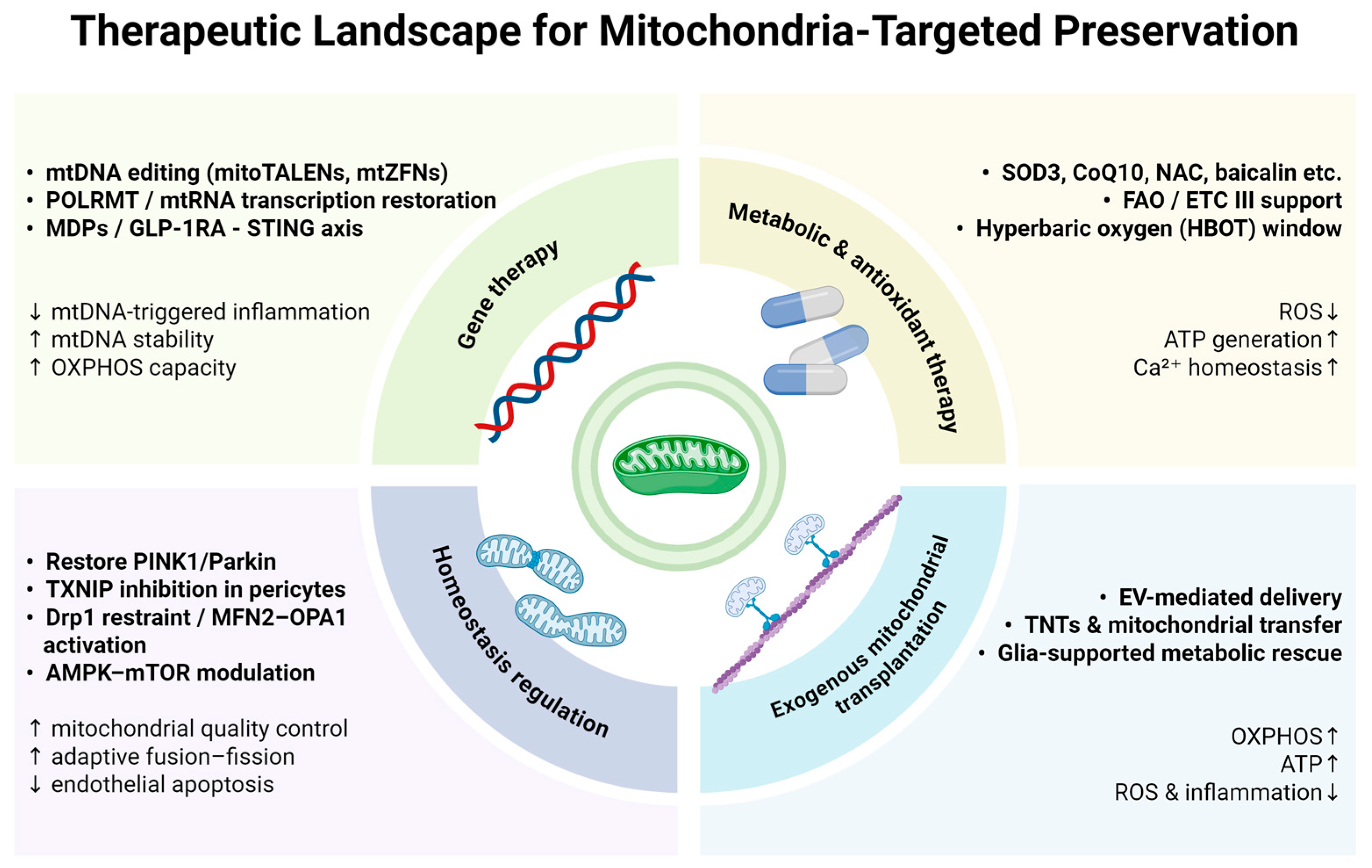

4. Therapeutic Strategies

4.1. Gene Therapy

4.2. Energy Metabolism Regulation and Antioxidant Therapy

4.3. Regulation of Mitochondrial Homeostasis

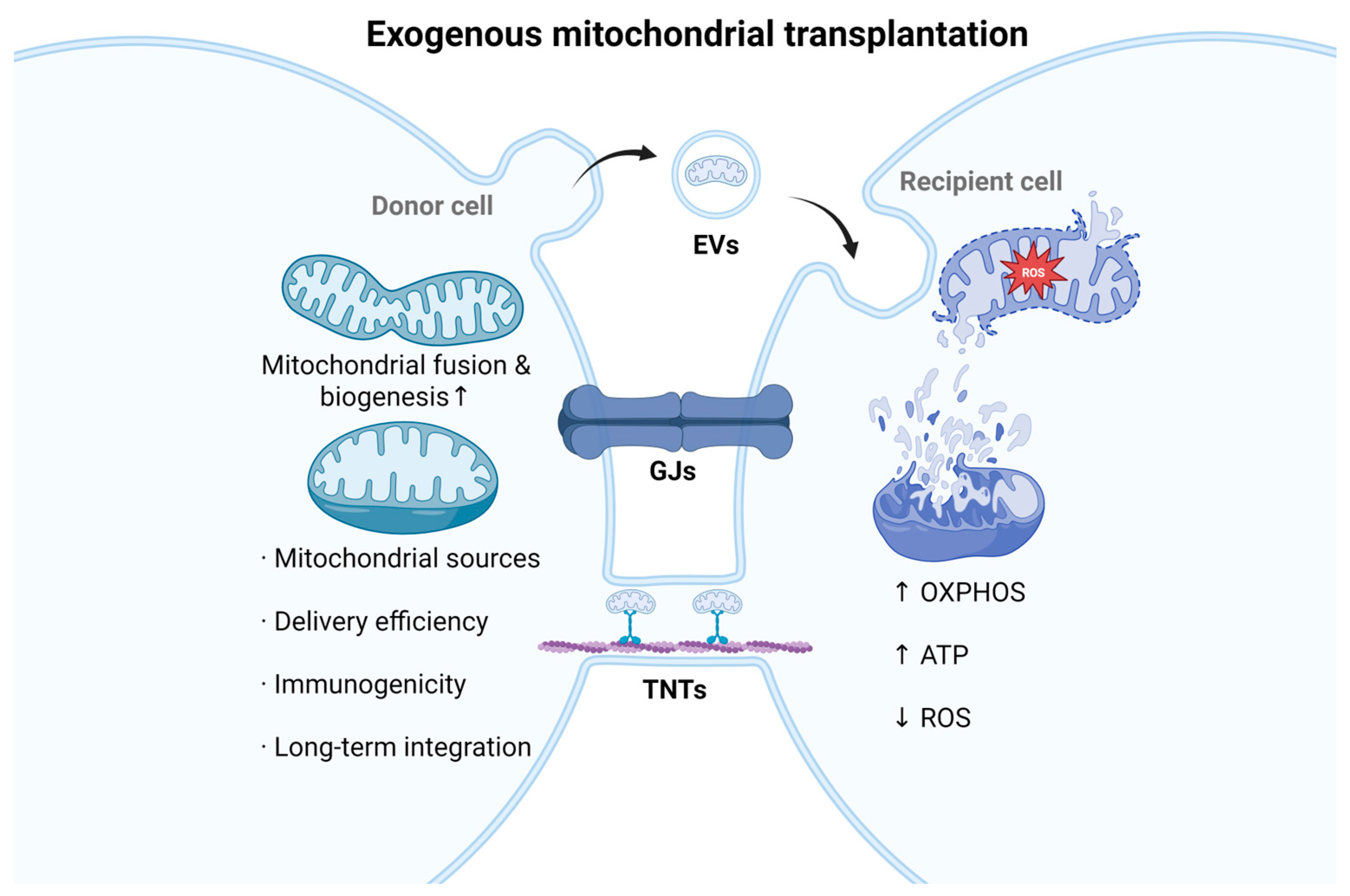

4.4. Exogenous Mitochondrial Transplantation

5. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ren, Y.; Liang, H.; Xie, M.; Zhang, M. Natural plant medications for the treatment of retinal diseases: The blood-retinal barrier as a clue. Phytomedicine 2024, 130, 155568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.H.-I.; Zou, B.; Chan, H.H.-L.; Tse, D.Y.-Y. Functional and structural changes in the neuroretina are accompanied by mitochondrial dysfunction in a type 2 diabetic mouse model. Eye Vis. 2023, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha-Vaz, J.; Bernardes, R.; Lobo, C. Blood-retinal barrier. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2011, 21, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, K.; Kushwah, N.; Maurya, M.; Pavlovich, M.C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J. Assessment of Inner Blood-Retinal Barrier: Animal Models and Methods. Cells 2023, 12, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L. Endothelial deletion of TBK1 contributes to BRB dysfunction via CXCR4 phosphorylation suppression. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yu, X.W.; Zhang, D.D.; Fan, Z.G. Blood-retinal barrier as a converging pivot in understanding the initiation and development of retinal diseases. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 2586–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Pericyte-Endothelial Interactions in the Retinal Microvasculature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Lee, S.J.; Vlahos, L.; Yuki, K.; Rada, C.C.; van Unen, V.; Vuppalapaty, M.; Chen, H.; Sura, A.; McCormick, A.K.; et al. Therapeutic blood-brain barrier modulation and stroke treatment by a bioengineered FZD4-selective WNT surrogate in mice. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Gu, L.; Luo, D.; Qiu, Q. Diabetic Macular Edema: Current Understanding, Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2022, 11, 3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkins-Netzer, O.; Niederer, R.; Greenwood, J.; Fabian, I.D.; Serlin, Y.; Friedman, A.; Lightman, S. Mechanisms of blood-retinal barrier disruption related to intraocular inflammation and malignancy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2024, 99, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudraraju, M.; Narayanan, S.P.; Somanath, P.R. Regulation of blood-retinal barrier cell-junctions in diabetic retinopathy. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 161, 105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Xiang, X.H.; Wei, J.; Zhang, P.B.; Xu, Q.; Liu, M.H.; Qu, L.-Q.; Wang, X.-X.; Yu, L.; Wu, A.-G.; et al. Raddeanin A Protects the BRB Through Inhibiting Inflammation and Apoptosis in the Retina of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurochem. Res. 2024, 49, 2197–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, D.; Huang, M.; Wang, B.; Yan, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X. mtDNA Maintenance and Alterations in the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2023, 21, 578–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, A.; Kallabis, S.; Gaedke, F.; Jüngst, C.; Boix, J.; Nüchel, J.; Maliphol, K.; Hofmann, J.; Schauss, A.C.; Krüger, M.; et al. Mitochondrial membrane proteins and VPS35 orchestrate selective removal of mtDNA. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.V.; Gitschlag, B.L.; Patel, M.R. Cellular mechanisms of mtDNA heteroplasmy dynamics. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 56, 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filograna, R.; Mennuni, M.; Alsina, D.; Larsson, N.G. Mitochondrial DNA copy number in human disease: The more the better? FEBS Lett. 2021, 595, 976–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J.; Liang, W.; Ding, G. AKAP1 contributes to impaired mtDNA replication and mitochondrial dysfunction in podocytes of diabetic kidney disease. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, P.; Anderson, N.S.; Shpilka, T.; Du, Y.; Naresh, N.U.; Li, R.; Zhu, L.J.; Luk, K.; Lavelle, J.; et al. LONP-1 and ATFS-1 sustain deleterious heteroplasmy by promoting mtDNA replication in dysfunctional mitochondria. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, B.; Yu, H.; Liu, S.; Wan, H.; Fu, S.; Liu, S.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, H.; Li, Q.; et al. Mitochondrial cristae architecture protects against mtDNA release and inflammation. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.Y.; Valdebenito, G.E.; Chacko, A.R.; Duchen, M.R. Rewiring cell signalling pathways in pathogenic mtDNA mutations. Trends Cell Biol. 2022, 32, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.S.; Hong, Z.; Wu, W.; Xiong, S.; Zhong, M.; Gao, X.; Malik, A.B. mtDNA Activates cGAS Signaling and Suppresses the YAP-Mediated Endothelial Cell Proliferation Program to Promote Inflammatory Injury. Immunity 2020, 52, 475–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, X.; Zheng, L.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, R.; Chen, J.; Gu, J.; Yin, Q.; Jiang, H.; et al. Non-canonical STING-PERK pathway dependent epigenetic regulation of vascular endothelial dysfunction via integrating IRF3 and NF- κ B in inflammatory response. Acta Pharm. Sinica B 2023, 13, 4765–4784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wen, S.; Tang, X.; Wen, Z.; Zhang, R.; Li, S.; Gao, R.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Fang, D.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists rescued diabetic vascular endothelial damage through suppression of aberrant STING signaling. Acta Pharm. Sinica B 2024, 14, 2613–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, C.; Sun, F.; Liu, C.; Huang, S.; Xu, T.; Zhang, C.; Ge, S. IQGAP1 promotes mitochondrial damage and activation of the mtDNA sensor cGAS-STING pathway to induce endothelial cell pyroptosis leading to atherosclerosis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 123, 110795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Liu, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, L. Cytoplasmic mtDNA clearance suppresses inflammatory immune responses. Trends Cell Biol. 2024, 34, 897–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Yucel, N.; Kim, B.; Arany, Z. Local Mitochondrial ATP Production Regulates Endothelial Fatty Acid Uptake and Transport. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, L.P.; Gil, H.J.; Gao, P.; Martinez, C.A.; Weinberg, S.E.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial complex III is necessary for endothelial cell proliferation during angiogenesis. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltanani, S.; Yumnamcha, T.; Gregory, A.; Elshal, M.; Shawky, M.; Ibrahim, A.S. Relative Importance of Different Elements of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation in Maintaining the Barrier Integrity of Retinal Endothelial Cells: Implications for Vascular-Associated Retinal Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, M.J.; Fu, P.P.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.X.; Ma, Z.R.; Cai, S.Z.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Q. Identification of the central role of RNA polymerase mitochondrial for angiogenesis. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2024, 22, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.W.; Jiang, K.; Shen, X.W.; Ma, Z.R.; Yan, X.M.; Xia, H.; Cao, X. The requirement of the mitochondrial protein NDUFS8 for angiogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.W.; Fung, T.S.; Baker, D.C.; Saoi, M.; Park, J.; Febres-Aldana, C.A.; Aly, R.G.; Cui, R.; Sharma, A.; Fu, Y.; et al. Cellular ATP demand creates metabolically distinct subpopulations of mitochondria. Nature 2024, 635, 746–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Lee, M.D.; Buckley, C.; Zhang, X.; McCarron, J.G. Mitochondrial ATP Production is Required for Endothelial Cell Control of Vascular Tone. Function 2022, 4, zqac063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Lee, M.D.; Heathcote, H.R.; Zhang, X.; Buckley, C.; Girkin, J.M.; Saunter, C.D.; McCarron, J.G. Mitochondrial ATP production provides long-range control of endothelial inositol trisphosphate-evoked calcium signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 737–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lee, M.D.; Buckley, C.; Wilson, C.; McCarron, J.G. Mitochondria regulate TRPV4-mediated release of ATP. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.R.; Gantner, B.N.; Sakiyama, M.J.; Kayzuka, C.; Shukla, S.; Lacchini, R.; Cunniff, B.; Bonini, M.G. ROS production by mitochondria: Function or dysfunction? Oncogene 2024, 43, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Gu, R.; Gan, D.; Hu, F.; Li, G.; Xu, G. Mitochondrial DNA drives noncanonical inflammation activation via cGAS-STING signaling pathway in retinal microvascular endothelial cells. Cell Commun. Signal. CCS 2020, 18, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Zhang, C.; Di, T.; Chen, L.; Zhao, W.; Wei, L.; Zhou, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y. Salvianolic acid B alleviates diabetic endothelial and mitochondrial dysfunction by down-regulating apoptosis and mitophagy of endothelial cells. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 3486–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negri, S.; Faris, P.; Moccia, F. Reactive Oxygen Species and Endothelial Ca2+ Signaling: Brothers in Arms or Partners in Crime? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Cellular mitophagy: Mechanism, roles in diseases and small molecule pharmacological regulation. Theranostics 2023, 13, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Long, H.; Hou, L.; Feng, B.; Ma, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, G. The mitophagy pathway and its implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Wang, X.; Yang, C.; Chen, F.; Shi, L.; Xu, W.; Wang, K.; Liu, B.; Wang, C.; Sun, D.; et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps drive intestinal microvascular endothelial ferroptosis by impairing Fundc1-dependent mitophagy. Redox Biol. 2023, 67, 102906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkon, L.L.; Strubbe-Rivera, J.O.; Bazil, J.N. Calcium Overload and Mitochondrial Metabolism. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbincius, J.F.; Elrod, J.W. Mitochondrial calcium exchange in physiology and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 893–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Rodriguez, M.; Bacskai, B.J. Mitochondria and Calcium in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Cell Signaling to Neuronal Cell Death. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.D.; Du, T.T.; Wang, C.Y.; Sun, L.N.; Wang, Y.Q. Calcium signaling crosstalk between the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria, a new drug development strategies of kidney diseases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 225, 116278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, H.Y.; Shao, J.; Zhu, L.; Xie, T.H.; Cai, J.; Wang, W.; Cai, M.X.; Wang, Z.L.; Yao, Y.; et al. GRP75 Modulates Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Coupling and Accelerates Ca(2+)-Dependent Endothelial Cell Apoptosis in Diabetic Retinopathy. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Sankaramoorthy, A.; Roy, S. Downregulation of Drp1 and Fis1 Inhibits Mitochondrial Fission and Prevents High Glucose-Induced Apoptosis in Retinal Endothelial Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grel, H.; Woznica, D.; Ratajczak, K.; Kalwarczyk, E.; Anchimowicz, J.; Switlik, W.; Jakiela, S. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Unraveling the Role of Fusion and Fission Processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudeau, K.; Molina, A.J.A.; Roy, S. High Glucose Induces Mitochondrial Morphology and Metabolic Changes in Retinal Pericytes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 8657–8664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, M.; Klug, N.R.; Mughal, A.; Koide, M.; Huerta de la Cruz, S.; Heppner, T.J.; Bonev, A.D.; Hill-Eubanks, D.; Nelson, M.T. Adenosine signaling activates ATP-sensitive K+ channels in endothelial cells and pericytes in CNS capillaries. Sci. Signal. 2022, 15, eabl5405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempf, S.; Popp, R.; Naeem, Z.; Frömel, T.; Wittig, I.; Klatt, S.; Fleming, I. Pericyte-to-Endothelial Cell Communication via Tunneling Nanotubes Is Disrupted by a Diol of Docosahexaenoic Acid. Cells 2024, 13, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S.; Guo, Y.; Fang, X.; Zheng, B.; Gao, W.; Yu, H.; Chen, Z.; Roman, R.J.; et al. Reduced pericyte and tight junction coverage in old diabetic rats are associated with hyperglycemia-induced cerebrovascular pericyte dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2021, 320, H549–H562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutto, R.A.; Rutter, K.M.; Giarmarco, M.M.; Parker, E.D.; Chambers, Z.S.; Brockerhoff, S.E. Cone photoreceptors transfer damaged mitochondria to Müller glia. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tong, B.; Xiong, J.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, H.; Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, F.; Yu, P.; Hu, Y.; et al. Identification of macrophage polarisation and mitochondria-related biomarkers in diabetic retinopathy. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahiri, A.; Sims, S.G.; Herstine, J.A.; Meyer, A.; Marshall, M.J.; Jahan, I.; Meares, G.P. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Amplifies Cytokine Responses in Astrocytes via a PERK/eIF2α/JAK1 Signaling Axis. Glia 2025, 73, 2273–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Qiao, G.; Qin, D.; Law, B.Y.-K.; Ren, F.; Wu, J.; Wu, A. Mitophagy and cGAS–STING crosstalk in neuroinflammation. Acta Pharm. Sinica B 2024, 14, 3327–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Alka, K. Mitochondrial Quality Control and Metabolic Memory Phenomenon Associated with Continued Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Kowluru, R.A. DNA Methylation-a Potential Source of Mitochondria DNA Base Mismatch in the Development of Diabetic Retinopathy. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Liu, C.; Hsu, J.W.; Chacko, S.; Minard, C.; Jahoor, F.; Sekhar, R.V. Glycine and N-acetylcysteine (GlyNAC) supplementation in older adults improves glutathione deficiency, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation, insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, genotoxicity, muscle strength, and cognition: Results of a pilot clinical trial. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salmina, A.B.; Kharitonova, E.V.; Gorina, Y.V.; Teplyashina, E.A.; Malinovskaya, N.A.; Khilazheva, E.D.; Mosyagina, A.I.; Morgun, A.V.; Shuvaev, A.N.; Salmin, V.V. Blood-Brain Barrier and Neurovascular Unit In Vitro Models for Studying Mitochondria-Driven Molecular Mechanisms of Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.H.; Chen, J.Y.; Zheng, J.L.; Zeng, H.X.; Chen, J.G.; Wu, C.H.; Zhuang, S.M. Fructose Metabolism in Tumor Endothelial Cells Promotes Angiogenesis by Activating AMPK Signaling and Mitochondrial Respiration. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 1249–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hameren, G.; Muradov, J.; Minarik, A.; Aboghazleh, R.; Orr, S.; Cort, S.; Andrews, L.; McKenna, C.; Pham, N.T.; MacLean, M.A.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction underlies impaired neurovascular coupling following traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 186, 106269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, N. Mitonuclear match: Optimizing fitness and fertility over generations drives ageing within generations. Bioessays 2011, 33, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristow, M.; Zarse, K. How increased oxidative stress promotes longevity and metabolic health: The concept of mitochondrial hormesis (mitohormesis). Exp. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Cui, S.; Xu, R.; Li, W.; Jiao, L.; Wang, T. ROS-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Aging Dis. 2024, 16, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salameh, T.S.; Mortell, W.G.; Logsdon, A.F.; Butterfield, D.A.; Banks, W.A. Disruption of the hippocampal and hypothalamic blood-brain barrier in a diet-induced obese model of type II diabetes: Prevention and treatment by the mitochondrial carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, topiramate. Fluids Barriers CNS 2019, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenin, R.; Thomas, S.M.; Gangaraju, R. Endothelial Activation and Oxidative Stress in Neurovascular Defects of the Retina. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 4742–4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Pang, Y.; Yan, H. Mechanism of apoptosis induced by the combined action of acrylamide and Elaidic acid through endoplasmic reticulum stress injury. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2024, 189, 114733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhu, C.; Wan, L.; Yao, W. The bidirectional roles of the cGAS-STING pathway in pain processing: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Ouyang, X.; Dong, Y.; Sarapultsev, A.; Luo, S.; Hu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Ouyang, X.; et al. Multifaceted functions of STING in human health and disease: From molecular mechanism to targeted strategy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Jia, Z.; Gong, W. Circulating Mitochondrial DNA Stimulates Innate Immune Signaling Pathways to Mediate Acute Kidney Injury. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 680648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Y.; Chen, Y.-S.; Jin, B.-Y.; Bilal, A. The cGAS-STING pathway in atherosclerosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1550930, Correction in Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1641100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ghosh, S.; Vaidya, T.; Bammidi, S.; Huang, C.; Shang, P.; Nair, A.P.; Chowdhury, O.; Stepicheva, N.A.; Strizhakova, A.; et al. Activated cGAS/STING signaling elicits endothelial cell senescence in early diabetic retinopathy. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e168945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Akasu, R.; Miyazaki, A. Calpain proteolytic systems counteract endothelial cell adaptation to inflammatory environments. Inflamm. Regen. 2020, 40, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shi, C.; He, M.; Xiong, S.; Xia, X.; Chen, X.; Shi, C.; He, M.; Xiong, S.; Xia, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.; Jiang, D.; Hu, X.; Du, W.; Ji, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Sho, T.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Mitocytosis, a migrasome-mediated mitochondrial quality-control process. Cell 2021, 184, 2896–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tábara, L.C.; Burr, S.P.; Frison, M.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Paupe, V.; Nie, Y.; Johnson, M.; Villar-Azpillaga, J.; Viegas, F.; Segawa, M.; et al. MTFP1 controls mitochondrial fusion to regulate inner membrane quality control and maintain mtDNA levels. Cell 2024, 187, 3619–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, A.; Samra, Y.A.; Elsherbiny, N.M.; Al-Shabrawey, M. Implication of Hyperhomocysteinemia in Blood Retinal Barrier (BRB) Dysfunction. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titi-Lartey, O.; Mohammed, I.; Amoaku, W.M. Frontiers. Toll-Like Receptor Signalling Pathways and the Pathogenesis of Retinal Diseases. Front. Ophthalmol. 2022, 2, 850394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.M.d.; Tewari, S.; Goldberg, A.F.X.; Kowluru, R.A. Mitochondria biogenesis and the development of diabetic retinopathy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1849–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Chen, Y.; Chai, S.; Lu, X.; Kang, L. O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modification: Emerging pathogenesis and a therapeutic target of diabetic nephropathy. Diabet. Med. 2024, 42, e15436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A. Diabetic Retinopathy: Mitochondria Caught in a Muddle of Homocysteine. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshaq, R.S.; Aldalati, A.M.Z.; Alexander, J.S.; Harris, N.R. Diabetic Retinopathy: Breaking the Barrier. Pathophysiol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Pathophysiol. 2017, 24, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Mishra, M. Therapeutic targets for altering mitochondrial dysfunction associated with diabetic retinopathy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2018, 22, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, F.; Dragoni, S.; Moccia, F.; Dragoni, S. The Calcium Signalling Profile of the Inner Blood-Retinal Barrier in Diabetic Retinopathy. Cells 2025, 14, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Zhu, L.; Bao, X.; Xie, T.H.; Cai, J.; Zou, J.; Wang, W.; Gu, S.; Li, Y.; Li, H.-Y.; et al. Inhibition of Drp1 ameliorates diabetic retinopathy by regulating mitochondrial homeostasis. Exp. Eye Res. 2022, 220, 109095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-Y.; Zhu, L.; Zheng, X.; Xie, T.-H.; Wang, W.; Zou, J.; Li, Y.; Li, H.-Y.; Cai, J.; Gu, S.; et al. TGR5 Activation Ameliorates Mitochondrial Homeostasis via Regulating the PKCδ/Drp1-HK2 Signaling in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 759421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serikbaeva, A.; Li, Y.; Ma, S.; Yi, D.; Kazlauskas, A. Resilience to diabetic retinopathy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2024, 101, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Z.; Sun, Y.; Yu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, S.; Lu, F.; Zhang, W. Hydrogen Sulphide modulating mitochondrial morphology to promote mitophagy in endothelial cells under high-glucose and high-palmitate. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 3190–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, G.; Dixit, A.; Nunemaker, C.S. A Putative Prohibitin-Calcium Nexus in β-Cell Mitochondria and Diabetes. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 7814628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, P.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, J. Microvascular destabilization and intricated network of the cytokines in diabetic retinopathy: From the perspective of cellular and molecular components. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, S.; Lo, A.C.Y.; Mi, Y.; Ren, K.; Yang, D.; Nian, S.; Lo, A.C.Y.; Mi, Y.; Ren, K.; Yang, D. Neurovascular unit in diabetic retinopathy: Pathophysiological roles and potential therapeutical targets. Eye Vis. 2021, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Mohammad, G. Epigenetics and Mitochondrial Stability in the Metabolic Memory Phenomenon Associated with Continued Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Eshwaran, R.; Beck, S.C.; Hammes, H.-P.; Wieland, T.; Feng, Y. Contribution of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway in the hyperglycemia-dependent and -independent breakdown of the retinal neurovascular unit. Mol. Metab. 2023, 73, 101736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.J.; Cascio, M.A.; Rosca, M.G. Diabetic Retinopathy: The Role of Mitochondria in the Neural Retina and Microvascular Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarniranta, K.; Uusitalo, H.; Blasiak, J.; Felszeghy, S.; Kannan, R.; Kauppinen, A.; Ferrington, D. Mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction and their impact on age-related macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 79, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noma, H.; Mimura, T.; Eguchi, S. Association of inflammatory factors with macular edema in branch retinal vein occlusion. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013, 131, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulovic-Sissawo, A.; Tocantins, C.; Diniz, M.S.; Weiss, E.; Steiner, A.; Tokic, S.; Madreiter-Sokolowski, C.T.; Pereira, S.P.; Hiden, U.; Kulovic-Sissawo, A.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Endothelial Progenitor Cells: Unraveling Insights from Vascular Endothelial Cells. Biology 2024, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, A.; Bruckner, D.; Rivera, F.J.; Reitsamer, H.A. Pericytes in the Retina. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1122, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester, S.J.; Preston, K.J.; Cooper, H.A.; Boyer, M.J.; Escoto, K.M.; Poltronetti, A.J.; Elliott, K.J.; Kuroda, R.; Miyao, M.; Sesaki, H.; et al. Mitochondrial Fission Mediates Endothelial Inflammation. Hypertension 2020, 76, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SQ, H.; KX, C.; CL, W.; PL, C.; YX, C.; YT, Z.; SH, Y.; ZX, B.; S, G.; MX, L.; et al. Decreasing mitochondrial fission ameliorates HIF-1α-dependent pathological retinal angiogenesis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2024, 45, 1438–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wen, F.; Yan, C.; Su, L.; Luo, J.; Chi, W.; Zhang, S. Frontiers. Mitophagy Protects the Retina Against Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Therapy-Driven Hypoxia via Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α Signaling. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 727822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Xia, F.; Mei, F.; Shi, S.; Robichaux, W.G.; Lin, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Cheng, X. Upregulation of Epac1 Promotes Pericyte Loss by Inducing Mitochondrial Fission, Reactive Oxygen Species Production, and Apoptosis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao-Malavé, V.; González-Zamora, J.; de la Puente, M.; Recalde, S.; Fernandez-Robredo, P.; Hernandez, M.; Layana, A.G.; de Viteri, M.S. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Age Related Macular Degeneration, Role in Pathophysiology, and Possible New Therapeutic Strategies. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaassen, I.; Van Noorden, C.J.; Schlingemann, R.O. Molecular basis of the inner blood-retinal barrier and its breakdown in diabetic macular edema and other pathological conditions. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2013, 34, 19–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, E.; Raoul, W.; Calippe, B.; Sahel, J.-A.; Guillonneau, X.; Paques, M.; Sennlaub, F. Experimental Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion Induces Upstream Pericyte Loss and Vascular Destabilization. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.D.; Kodati, B.; Stankowska, D.L.; Krishnamoorthy, R.R. Role of mitophagy in ocular neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1299552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lendzioszek, M.; Bryl, A.; Poppe, E.; Zorena, K.; Mrugacz, M.; Lendzioszek, M.; Bryl, A.; Poppe, E.; Zorena, K.; Mrugacz, M. Retinal Vein Occlusion–Background Knowledge and Foreground Knowledge Prospects—A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Deng, J.; Sun, D.; Chen, S.; Yao, X.; Wang, N.; Zhang, J.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; et al. FBXW7 alleviates hyperglycemia-induced endothelial oxidative stress injury via ROS and PARP inhibition. Redox Biol. 2022, 58, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sazonova, M.A.; Ryzhkova, A.I.; Sinyov, V.V.; Sazonova, M.D.; Kirichenko, T.V.; Doroschuk, N.A.; Sobenin, I.A. Mutations of mtDNA in some Vascular and Metabolic Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 102530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtashami, Z.; Singh, M.K.; Neto, F.T.; Salimiaghdam, N.; Hasanpour, H.; Kenney, M.C. Mitochondrial Open Reading Frame of the 12S rRNA Type-c: Potential Therapeutic Candidate in Retinal Diseases. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Kim, M.; Oh, S.B.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, C.; Kim, T.Y.; Park, Y.H. Superoxide dismutase 3 prevents early stage diabetic retinopathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battaglia, A.M.; Chirillo, R.; Aversa, I.; Sacco, A.; Costanzo, F.; Biamonte, F. Ferroptosis and Cancer: Mitochondria Meet the “Iron Maiden” Cell Death. Cells 2020, 9, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.; Huang, C.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Tan, N. GPR30-driven fatty acid oxidation targeted by ginsenoside Rd maintains mitochondrial redox homeostasis to restore vascular barrier in diabetic retinopathy. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.S.; Truong, T.T.; Bortolasci, C.C.; Spolding, B.; Panizzutti, B.; Swinton, C.; Kim, J.H.; Hernandez, D.; Kidnapillai, S.; Gray, L.; et al. The potential of baicalin to enhance neuroprotection and mitochondrial function in a human neuronal cell model. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 2487–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uozumi, H.; Kawakami, S.; Matsui, Y.; Mori, S.; Sato, A. Passion fruit seed extract protects hydrogen peroxide-induced cell damage in human retinal pigment epithelium ARPE-19 cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Peng, S.; Duan, B.; Shao, Y.; Li, X.; Zou, H.; Fan, H.; You, Z. Isoquercetin Alleviates Diabetic Retinopathy Via Inhibiting p53-Mediated Ferroptosis. Cell Biol. Int. 2025, 49, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C.H.I.; Zuo, B.; Chan, H.H.L.; Leung, T.W.; Abokyi, S.; Catral, K.P.C.; Tse, D.Y.Y. Coenzyme Q10 eyedrops conjugated with vitamin E TPGS alleviate neurodegeneration and mitochondrial dysfunction in the diabetic mouse retina. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1404987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.P.; Chidlow, G.; Wall, G.M.; Casson, R.J. N-acetylcysteine amide and di- N-acetylcysteine amide protect retinal cells in culture via an antioxidant action. Exp. Eye Res. 2024, 248, 110074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deppe, L.; Mueller-Buehl, A.M.; Tsai, T.; Erb, C.; Dick, H.B.; Joachim, S.C. Protection against Oxidative Stress by Coenzyme Q10 in a Porcine Retinal Degeneration Model. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.; Recalde, S.; Bezunartea, J.; Moreno-Orduña, M.; Belza, I.; Chas-Prat, A.; Perugini, E.; Garcia-Layana, A.; Fernandez-Robredo, P. The Scavenging Activity of Coenzyme Q10 Plus a Nutritional Complex on Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schottlender, N.; Gottfried, I.; Ashery, U. Hyperbaric Oxygen Treatment: Effects on Mitochondrial Function and Oxidative Stress. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xiang, J.; Chen, Y.; He, C.; Tong, J.; Liao, Y.; Lei, H.; Sun, L.; Yao, G.; Xie, Z. MiR-125a-5p in MSC-derived small extracellular vesicles alleviates Müller cells injury in diabetic retinopathy by modulating mitophagy via PTP1B pathway. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Dong, X.; Pan, Y.; Sun, X.; Luo, Y. Ginsenoside Ro prevents endothelial injury via promoting Epac1/AMPK- mediated mitochondria protection in early diabetic retinopathy. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 211, 107562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wang, T.; Sun, G.-F.; Xiao, J.-X.; Jiang, L.-P.; Tou, F.-F.; Qu, X.-H.; Han, X.-J. Metformin protects against retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury through AMPK-mediated mitochondrial fusion. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 205, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Ji, Z.; Gao, J.; Fan, J.; Hou, J.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Z. Poldip2 Aggravates inflammation in diabetic retinopathy by impairing mitophagy via the AMPK/ULK1/Pink1 pathway. Life Sci. 2025, 373, 123681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, X.; Ma, J.; Xu, G.; Sun, Z. SHP-1 knockdown suppresses mitochondrial biogenesis and aggravates mitochondria-dependent apoptosis induced by all trans retinal through the STING/AMPK pathways. Mol. Med. 2022, 28, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.-Y.; Singh, K.; Sheshadri, P.; Valdebenito, G.E.; Chacko, A.R.; Besada, M.A.C.; Liang, X.F.; Kabir, L.; Pitceathly, R.D.S.; Szabadkai, G.; et al. Inhibition of the PI3K-AKT-MTORC1 axis reduces the burden of the m.3243A>G mtDNA mutation by promoting mitophagy and improving mitochondrial function. Autophagy 2025, 21, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, T.S.; Hosoya, K.I.; Terasaki, T.; Singh, L.P. Critical role of TXNIP in oxidative stress, DNA damage and retinal pericyte apoptosis under high glucose: Implications for diabetic retinopathy. Exp. Cell Res. 2013, 319, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Sesaki, H.; Roy, S. Reduced Levels of Drp1 Protect against Development of Retinal Vascular Lesions in Diabetic Retinopathy. Cells 2021, 10, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Lenahan, C.; Lian, L.; Ou, Y.; He, Y. Mitochondrial Dynamics: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Ischemic Stroke. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 721428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Qian, Y.; Huo, D.; Wang, S.; Qian, Q. Tanshinone IIa protects retinal endothelial cells against mitochondrial fission induced by methylglyoxal through glyoxalase 1. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 857, 172419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Liu, X.; Qu, W.; Zhang, X.; Zou, Y.; Lin, X.; Hu, W.; Gao, R.; He, Y.; Zhou, S.; et al. Astragaloside IV Relieves Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Damage and Dysfunction in Diabetic Mice Endothelial Progenitor Cells by Regulating the GSK-3β/Nrf2 Axis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2025, 197, 3964–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.-R.; Li, H.-P.; Cai, S.-Z.; Du, S.-Y.; Chen, X.; Yao, J.; Cao, X.; Zhen, Y.-F.; Wang, Q. The mitochondrial protein TIMM44 is required for angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, J.; Zeng, T.; Roux, M.; Lazar, D.; Chen, L.; Tudzarova, S. The Role of HIF1α-PFKFB3 Pathway in Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 2505–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.C. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Its Involvement in Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2020, 15, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borcherding, N.; Brestoff, J.R. The power and potential of mitochondria transfer. Nature 2023, 623, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhou, Y. Frontiers. The Functions, Methods, and Mobility of Mitochondrial Transfer Between Cells. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 672781. [Google Scholar]

- Velarde, F.; Ezquerra, S.; Delbruyere, X.; Caicedo, A.; Hidalgo, Y.; Khoury, M. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated transfer of mitochondria: Mechanisms and functional impact. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2022, 79, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, A.; Burch, A.; Dave, K.M.; Sreeram, A.; Reynolds, M.J.; Dobbins, D.X.; Kamate, Y.S.; Zhao, W.; Sabatelle, C.; Joy, G.M.; et al. Microvesicles transfer mitochondria and increase mitochondrial function in brain endothelial cells. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2021, 338, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Chen, F.-X.; Zhou, H.; Lu, Y.-Y.; Tan, H.; Yu, S.-J.; Yuan, J.; Liu, H.; Meng, W.; Jin, Z.-B. Bioenergetic Crosstalk between Mesenchymal Stem Cells and various Ocular Cells through the intercellular trafficking of Mitochondria. Theranostics 2020, 10, 7260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; Chen, F.; Jiang, D.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Z.B. ROCK inhibitor enhances mitochondrial transfer via tunneling nanotubes in retinal pigment epithelium. Theranostics 2024, 14, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cell Type | Mechanism | Effects on the iBRB | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endothelial cells | mtDNA mutations and reduced copy number impair OXPHOS | Energy depletion and oxidative stress trigger endothelial apoptosis, inflammatory activation, and tight-junction disruption | [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] |

| Impaired ATP synthesis and dysfunction of mitochondrial ETC complexes I/III | Loss of cytoskeletal stability and tight-junction integrity; increased endothelial permeability | [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] | |

| Excessive ROS generation via ETC complexes I/III and activation of NF-κB/MAPK signaling | Amplified oxidative stress, endothelial apoptosis, degradation of junctional proteins (ZO-1, Occludin), and up-regulation of pro-inflammatory mediators | [35,36,37,38] | |

| Defective PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy and Fundc1-dependent flux blockade | Accumulation of damaged mitochondria leads to chronic ROS elevation and endothelial cell death | [39,40,41] | |

| Disturbed Ca2+ homeostasis via TRPV4–MCU overactivation and VDAC1–GRP75–IP3R coupling | Mitochondrial Ca2+ overload, mPTP opening, ROS bursts, cytoskeletal collapse, and barrier leakage | [42,43,44,45,46] | |

| Imbalance between mitochondrial fusion and fission (Drp1/Fis1, MFN2/OPA1) | Mitochondrial fragmentation, cytochrome c release, reduced stress adaptability, and endothelial barrier disruption | [47,48] | |

| Pericytes | Mitochondrial fragmentation and metabolic impairment | Decreased contractility, microvascular destabilization, and impaired support for endothelial cells | [30,49,50,51,52] |

| TXNIP-mediated excessive mitophagy and oxidative stress | Mitochondrial depletion, apoptosis, and pericyte loss leading to capillary regression | [39,40] | |

| Glial cells | ER–mitochondrial crosstalk (PERK/eIF2α/JAK1 axis) and redox imbalance | Enhanced cytokine release, loss of neurovascular coupling, and diminished barrier-supportive functions | [53,54,55,56] 1 |

| Mechanism | Key Pathways | DR-Specific Alterations and Effects on iBRB Cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| mtDNA mutations and instability | Reduced mtDNA copy number; ND1/ND6; cytochrome b; POLRMT deficiency; AKAP1 loss | High glucose increases mtDNA damage and cytoplasmic mtDNA leakage, activating cGAS–STING and NF-κB, which trigger VEGF/IL-6 release and endothelial inflammation | [90,91,92] |

| Energy deficiency and OXPHOS impairment | Complex I/III dysfunction; NDUFS8 loss; POLRMT depletion; ATP synthase inhibition | Persistent ATP shortage reduces endothelial migration and barrier repair, weakens pericyte contractility, and impairs neurovascular coupling under hyperglycemia | [82,83] |

| ROS generation and oxidative stress | Complex I/III—derived ROS; NOX activation via AGEs–RAGE; NF-κB/MAPK pathways | Hyperglycemia and AGEs drive excessive ROS, causing endothelial apoptosis, tight-junction degradation (ZO-1, Occludin), and pericyte cytoskeletal oxidation | [82,83,84] |

| Mitophagy dysregulation | Endothelium: PINK1/Parkin deficiency and mTOR overactivation; Pericytes: TXNIP-driven excess mitophagy | Endothelial cells retain damaged mitochondria → mtROS and apoptosis; Pericytes undergo mitochondrial depletion → bioenergetic collapse and cell loss | [85,86,87,88,89] |

| Fusion–fission imbalance | Drp1/Fis1 upregulation; MFN2/OPA1 downregulation; PGC-1α suppression | O-GlcNAc-modified Drp1 activation and loss of fusion proteins promote mitochondrial fragmentation and apoptosis, driving progressive iBRB breakdown | [82,83,85,86,87,88,89] |

| Epigenetic metabolic memory | Persistent Drp1 activation; MFN2 promoter methylation; histone modifications | Long-term mitochondrial stress induces stable epigenetic reprogramming, maintaining oxidative and inflammatory vulnerability after glycemic normalization | [93] 1 |

| Mechanism | Key Pathways | RVO-Specific Alterations and Effects on iBRB Cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute energy deficit | Venous obstruction; acute ischemia; OXPHOS inhibition | Rapid ATP depletion, shift to anaerobic glycolysis, cytosolic acidosis, and early endothelial energy failure that destabilizes the barrier | [83,84,103] |

| Reperfusion-driven oxidative burst | Electron leakage from ETC complexes I/III; mPTP opening; Ca2+ influx | Intense oxidative surge leading to mitochondrial swelling and endothelial apoptosis, with transient and spatially heterogeneous injury patterns characterized by central necrosis and peripheral reversible depolarization | [96,100,101,102] |

| mtDNA-mediated sterile inflammation | Leakage of mtDNA/N-formyl peptides; activation of TLR9 and cGAS–STING;NF-κB/type I IFN | Upregulation of IL-6, TNF-α, and VEGF, increased endothelial permeability, and enhanced leukocyte adhesion; inflammation exhibits time-dependent behavior, where transient activation may aid repair but sustained activation drives irreversible breakdown | [36,96,97,98,99] |

| Biphasic changes in mitochondrial dynamics |

Ischemia: excessive Drp1 activation; MFN2/OPA1 downregulation

Reperfusion: PINK1/Parkin-dependent clearance | During ischemia, excessive mitochondrial fragmentation and cytochrome-c release occur, while the early reperfusion phase requires controlled fission to remove damaged mitochondria; persistent Drp1 overactivation impairs network recovery and prolongs endothelial loss | [100,101,102] |

| Pericyte mitochondrial dysfunction | ATP depletion; Ca2+ overload; ROS elevation | Impaired pericyte contractility and apoptosis reduce mural coverage, weaken microvascular support, and exacerbate vascular leakage | [7,103,106] |

| Endothelial–pericyte mitochondrial crosstalk | ROS–cytokine feedback; gap-junction signaling | Bidirectional amplification of oxidative and inflammatory signals generates a feed-forward injury loop that promotes sustained iBRB instability and worsening hypoxia | [7,104,105,106] 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Jin, Q.; Li, J.; Li, K. When Mitochondria Falter, the Barrier Fails: Mechanisms of Inner Blood-Retinal Barrier (iBRB) Injury and Opportunities for Mitochondria-Targeted Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11984. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411984

Chen Z, Jin Q, Li J, Li K. When Mitochondria Falter, the Barrier Fails: Mechanisms of Inner Blood-Retinal Barrier (iBRB) Injury and Opportunities for Mitochondria-Targeted Repair. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11984. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411984

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ziyi, Qianzi Jin, Jiajun Li, and Keran Li. 2025. "When Mitochondria Falter, the Barrier Fails: Mechanisms of Inner Blood-Retinal Barrier (iBRB) Injury and Opportunities for Mitochondria-Targeted Repair" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11984. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411984

APA StyleChen, Z., Jin, Q., Li, J., & Li, K. (2025). When Mitochondria Falter, the Barrier Fails: Mechanisms of Inner Blood-Retinal Barrier (iBRB) Injury and Opportunities for Mitochondria-Targeted Repair. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11984. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411984