Development of αβ and γδ T Cells in the Thymus and Methods of Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

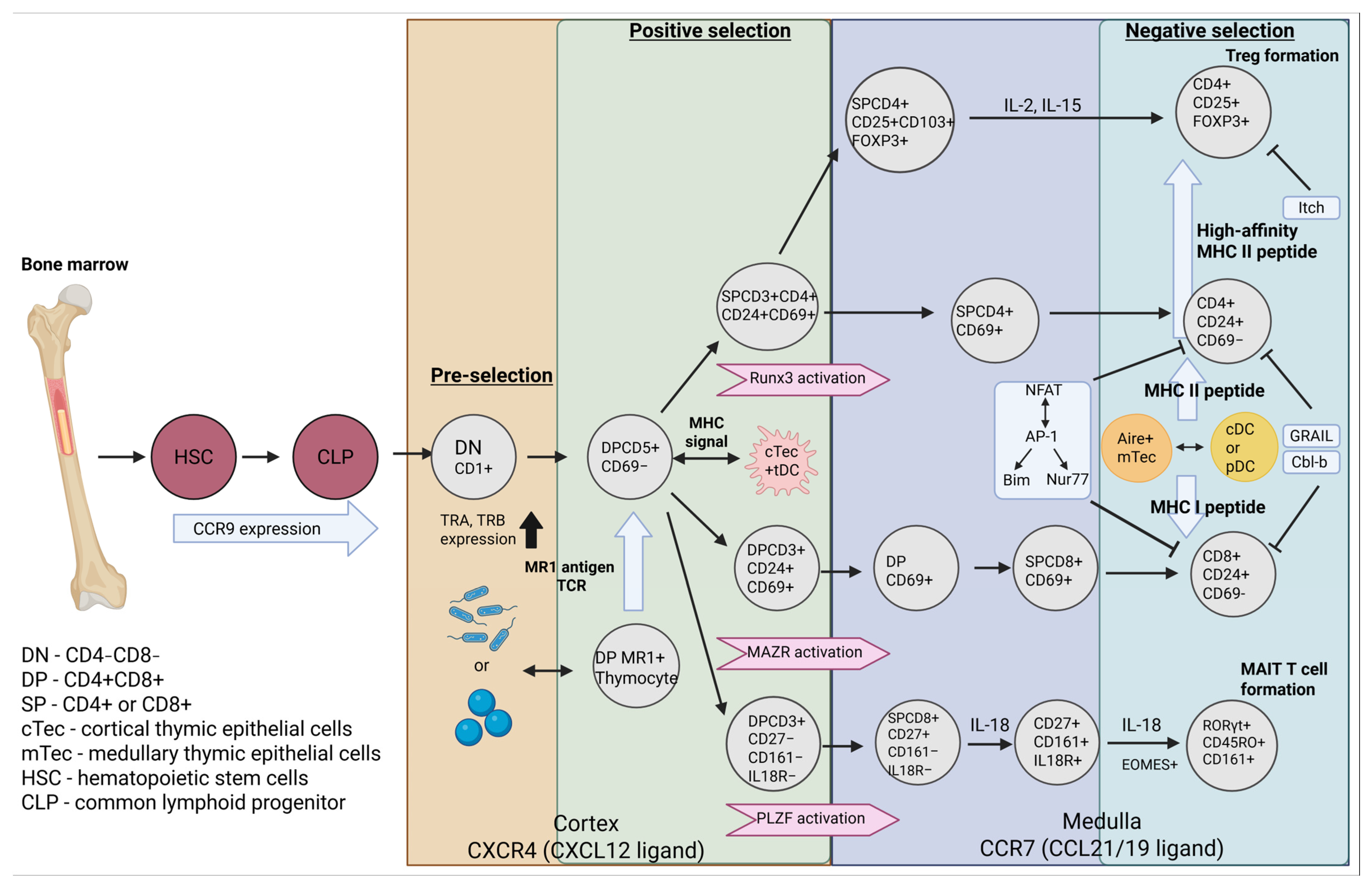

2. Starting Point of αβ and γδ Thymocyte Formation

3. Formation αβ TCR T Cells

4. Formation γδ TCR T Cells

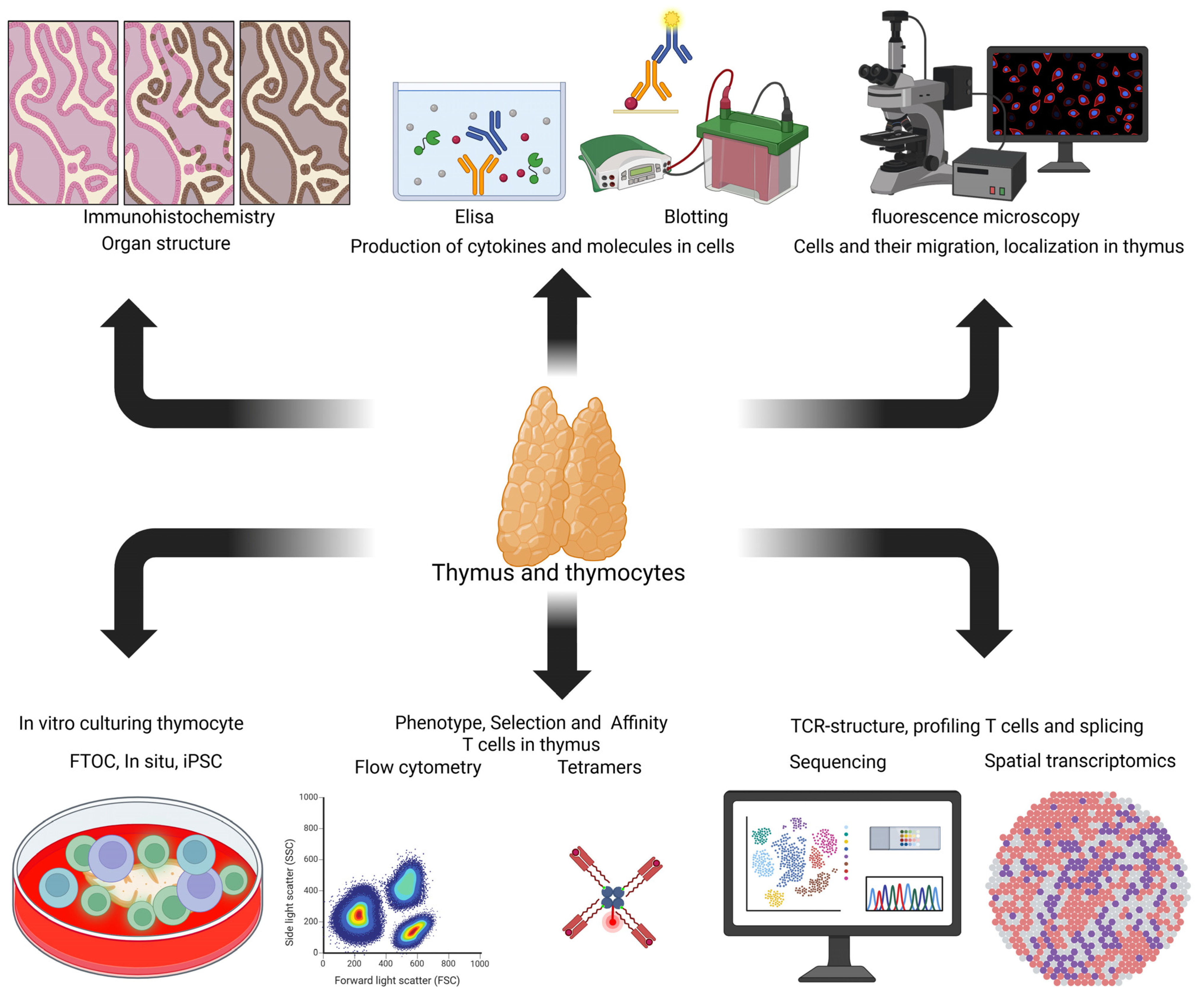

4.1. Vδ1+ T Cell Population

4.2. Vδ2+ T Cell Population

5. Affinity and Its Role in T Cell Formation

6. Methods for Analyzing the Processes of T Cell Formation in the Thymus

6.1. Experimental Models for Studying Thymopoiesis In Vitro

6.2. Analytical Methods for Studying the Thymus

7. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raica, M.; Cîmpean, A.M.; Encică, S.; Cornea, R. Involution of the thymus: A possible diagnostic pitfall. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2007, 48, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, H.T.; Zúñiga-Pflücker, J.C. Zoned out: Functional mapping of stromal signaling microenvironments in the thymus. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 649–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouse, H.; Suban, M.; Suban, M.G.; Gunasegaran, J.P. Histological and histometrical study on human fetal thymus. Health Sci. 2019, 8, 90–109. [Google Scholar]

- Takada, K.; Ohigashi, I.; Kasai, M.; Nakase, H.; Takahama, Y. Development and function of cortical thymic epithelial cells. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014, 373, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, L.; Kyewski, B.; Allen, P.M.; Hogquist, K.A. Positive and negative selection of the T cell repertoire: What thymocytes see (and don’t see). Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.S.; Venanzi, E.S.; Klein, L.; Chen, Z.; Berzins, S.P.; Turley, S.J.; von Boehmer, H.; Bronson, R.; Dierich, A.; Benoist, C.; et al. Projection of an immunological self shadow within the thymus by the aire protein. Science 2002, 298, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Givony, T.; Leshkowitz, D.; Del Castillo, D.; Nevo, S.; Kadouri, N.; Dassa, B.; Gruper, Y.; Khalaila, R.; Ben-Nun, O.; Gome, T.; et al. Thymic mimetic cells function beyond self-tolerance. Nature 2023, 622, 164–172, Correction in: Nature 2023, 624, E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, C.; Bennaceur-Griscelli, A.; Louache, F.; Vainchenker, W.; Coulombel, L. Identification of human T-lymphoid progenitor cells in CD34+ CD38low and CD34+ CD38+ subsets of human cord blood and bone marrow cells using NOD-SCID fetal thymus organ cultures. Br. J. Haematol. 1999, 104, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, L.; Boehm, T. Three chemokine receptors cooperatively regulate homing of hematopoietic progeni-tors to the embryonic mouse thymus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7517–7522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Chen, C.H.; Cooper, M.D. Thymic function can be accurately monitored by the level of recent T cell emigrants in the circulation. Immunity 1998, 8, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, C.; Heinzel, K.; Bleul, C.C. Homing of immature thymocytes to the subcapsular microenvironment within the thymus is not an absolute requirement for T cell development. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004, 34, 3652–3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karima, G.; Kim, H.D. Unlocking the regenerative key: Targeting stem cell factors for bone renewal. J Tissue Eng. 2024, 15, 20417314241287491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenins, L.; Gill, J.W.; Boyd, R.L.; Holländer, G.A.; Wodnar-Filipowicz, A. Intrathymic expression of Flt3 ligand enhances thymic recovery after irradiation. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hozumi, K.; Mailhos, C.; Negishi, N.; Hirano, K.; Yahata, T.; Ando, K.; Zuklys, S.; HollänDer, G.A.; Shima, D.T.; Habu, S. Delta-like 4 is indispensable in thymic environment specific for T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 2507–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Famili, F.; Wiekmeijer, A.S.; Staal, F.J. The development of T cells from stem cells in mice and humans. Future Sci. OA 2017, 3, FSO186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboloff, J.; Kappes, D.J. (Eds.) Signaling Mechanisms Regulating T Cell Diversity and Function; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M.E.; Ciofani, M. Regulation of γδ T Cell Effector Diversification in the Thymus. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinzawa, M.; Moseman, E.A.; Gossa, S.; Mano, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Guinter, T.; Alag, A.; Chen, X.; Cam, M.; McGavern, D.B.; et al. Reversal of the T Cell Immune System Reveals the Molecular Basis for T Cell Lineage Fate Determination in the Thymus. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turchinovich, G.; Hayday, A.C. Skint-1 Identifies a Common Molecular Mechanism for the Development of Interferon-γ-Secreting Versus Interleukin-17-Secreting γδ T Cells. Immunity 2011, 35, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, W.N.; Chang, C.F.; Fischer, A.M.; Li, M.; Hedrick, S.M. The Erk2 MAPK regulates CD8 T cell proliferation and survival. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 7617–7629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laethem, F.; Tikhonova, A.N.; Pobezinsky, L.A.; Tai, X.; Kimura, M.Y.; Le Saout, C.; Guinter, T.I.; Adams, A.; Sharrow, S.O.; Bernhardt, G.; et al. Lck Availability During Thymic Selection Determines the Recognition Specificity of the T Cell Repertoire. Cell 2013, 154, 1326–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, E.H.; Weiss, A. Distinct Roles for Syk and ZAP-70 During Early Thymocyte Development. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 1703–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagattuta, K.A.; Kohlgruber, A.C.; Abdelfattah, N.S.; Nathan, A.; Rumker, L.; Birnbaum, M.E.; Elledge, S.J.; Raychaudhuri, S. The T Cell Receptor Sequence Influences the Likelihood of T Cell Memory Formation. bioRxiv 2023, Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhang, X.; Kovalovsky, D. PLZF Controls the Development of Fetal-Derived IL-17+Vγ6+ γδ T Cells. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 4273–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, H.; Romero-Wolf, M.; Yui, M.A.; Ungerbäck, J.; Quiloan, M.L.G.; Matsumoto, M.; Nakayama, K.I.; Tanaka, T.; Rothenberg, E.V. Bcl11b sets pro-T cell fate by site-specific cofactor recruitment and by repressing Id2 and Zbtb16. Nat Immunol. 2018, 19, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda-Lennikov, M.; Ohigashi, I.; Takahama, Y. Tissue-Specific Proteasomes in Generation of MHC Class I Peptides and CD8+ T Cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2022, 77, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arudchelvan, Y.; Nishimura, Y.; Tokuda, N.; Sawada, T.; Shinozaki, F.; Fukumoto, T. Differential Expression of MHC Class II Antigens and Cathepsin L by Subtypes of Cortical Epithelial Cells in the Rat Thymus: An Immunoelectron Microscopic Study. J. Electron. Microsc. 2002, 51, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozga, A.J.; Moalli, F.; Abe, J.; Swoger, J.; Sharpe, J.; Zehn, D.; Kreutzfeldt, M.; Merkler, D.; Ripoll, J.; Stein, J.V. pMHC Affinity Controls Duration of CD8+ T Cell-DC Interactions and Imprints Timing of Effector Differentiation Versus Expansion. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 2811–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puech, P.H.; Bongrand, P. Mechanotransduction as a Major Driver of Cell Behaviour: Mechanisms, and Relevance to Cell Organization and Future Research. Open Biol. 2021, 11, 210256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, A.C.; Grainger, J.R.; Xiong, Y.; Kanno, Y.; Chu, H.H.; Wang, L.; Naik, S.; dos Santos, L.; Wei, L.; Jenkins, M.K.; et al. The Transcription Factors Thpok and LRF Are Necessary and Partly Redundant for T Helper Cell Differentiation. Immunity 2012, 37, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twu, Y.C.; Teh, H.S. The ThPOK Transcription Factor Differentially Affects the Development and Function of Self-Specific CD8+ T Cells and Regulatory CD4+ T Cells. Immunology 2014, 141, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istaces, N.; Splittgerber, M.; Lima Silva, V.; Nguyen, M.; Thomas, S.; Le, A.; Achouri, Y.; Calonne, E.; Defrance, M.; Fuks, F.; et al. EOMES Interacts with RUNX3 and BRG1 to Promote Innate Memory Cell Formation Through Epigenetic Reprogramming. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitti, B.; Hoffer, E.; Zheng, W.; Pandey, R.V.; Schlums, H.; Perinetti Casoni, G.; Fusi, I.; Nguyen, L.; Kärner, J.; Kokkinou, E.; et al. Human Skin-Resident CD8+ T Cells Require RUNX2 and RUNX3 for Induction of Cytotoxicity and Expression of the Integrin CD49a. Immunity 2023, 56, 1285–1302.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappes, D.J. Expanding Roles for ThPOK in Thymic Development. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 238, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.; Sakaguchi, S.; Tenno, M.; Kopf, A.; Boucheron, N.; Carpenter, A.C.; Egawa, T.; Taniuchi, I.; Ellmeier, W. Cd8 Enhancer E8I and Runx Factors Regulate CD8α Expression in Activated CD8+ T Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18330–18335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.Q.; Shi, Y.; Reid, H.H.; Boyd, R.L.; Khattabi, M.; El-Omrani, H.Y.; Zheng, P.; Liu, Y.; Bai, X. CD24 on Thymic APCs Regulates Negative Selection of Myelin Antigen-Specific T Lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 924–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, I.; Nagata, T.; Tada, T.; Nakayama, T. CD69 Cell Surface Expression Identifies Developing Thymocytes Which Audition for T Cell Antigen Receptor-Mediated Positive Selection. Int. Immunol. 1993, 5, 1139–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozai, M.; Kubo, Y.; Katakai, T.; Kondo, H.; Kiyonari, H.; Schaeuble, K.; Luther, S.A.; Ishimaru, N.; Ohigashi, I.; Takahama, Y. Essential Role of CCL21 in Establishment of Central Self-Tolerance in T Cells. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 1925–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, B.; White, A.J.; Parnell, S.M.; Henley, P.M.; Jenkinson, W.E.; Anderson, G. Progressive Changes in CXCR4 Expression That Define Thymocyte Positive Selection Are Dispensable For Both Innate and Conventional αβT-cell Development. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.Y.; Jung, K.C.; Park, H.J.; Chung, D.H.; Song, J.S.; Yang, S.D.; Simpson, E.; Park, S.H. Thymocyte-Thymocyte Interaction for Efficient Positive Selection and Maturation of CD4 T Cells. Immunity 2005, 23, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, P.; Org, T.; Rebane, A. Transcriptional Regulation by AIRE: Molecular Mechanisms of Central Tolerance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.S.; Venanzi, E.S.; Chen, Z.; Berzins, S.P.; Benoist, C.; Mathis, D. The Cellular Mechanism of Aire Control of T Cell Tolerance. Immunity 2005, 23, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevyrev, D.; Tereshchenko, V.; Kozlov, V.; Sennikov, S. Phylogeny, Structure, Functions, and Role of AIRE in the Formation of T-Cell Subsets. Cells 2022, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passos, G.A.; Speck-Hernandez, C.A.; Assis, A.F.; Mendes-da-Cruz, D.A. Update on Aire and Thymic Negative Selection. Immunology 2018, 153, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez Arias, D.A.; McCarty, N.; Lu, L.; Maldonado, R.A.; Shinohara, M.L.; Cantor, H. Unexpected Role of Clathrin Adaptor AP-1 in MHC-Dependent Positive Selection of T Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 2556–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Bouillet, P.; Robati, M.; Belz, G.T.; Davey, G.M.; Strasser, A. Loss of Bim Increases T Cell Production and Function in Interleukin 7 Receptor-Deficient Mice. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 200, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lith, S.C.; van Os, B.W.; Seijkens, T.T.P.; de Vries, C.J.M. ‘Nur’turing Tumor T Cell Tolerance and Exhaustion: Novel Function for Nuclear Receptor Nur77 in Immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2020, 50, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sade, H.; Sarin, A. Reactive Oxygen Species Regulate Quiescent T-Cell Apoptosis via the BH3-Only Proapoptotic Protein BIM. Cell Death Differ. 2004, 11, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Wang, Z.E.; Shen, L.; Schroeder, A.; Eckalbar, W.; Weiss, A. Cbl-b Deficiency Prevents Functional But Not Phenotypic T Cell Anergy. J. Exp. Med. 2021, 218, e20202477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurieva, R.I.; Zheng, S.; Jin, W.; Chung, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Martinez, G.J.; Reynolds, J.M.; Wang, S.-L.; Lin, X.; Sun, S.-C.; et al. The E3 Ubiquitin Ligase GRAIL Regulates T Cell Tolerance and Regulatory T Cell Function by Mediating T Cell Receptor-CD3 Degradation. Immunity 2010, 32, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; He, N.; Zhang, N.; Quan, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Yu, R.T.; Atkins, A.R.; Zhu, R.; Yang, C.; et al. NCoR1 Restrains Thymic Negative Selection by Repressing Bim Expression to Spare Thymocytes Undergoing Positive Selection. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettini, M.L.; Vignali, D.A. Development of Thymically Derived Natural Regulatory T Cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1183, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, X.; Indart, A.; Rojano, M.; Guo, J.; Apenes, N.; Kadakia, T.; Craveiro, M.; Alag, A.; Etzensperger, R.; Badr, M.E.; et al. How Autoreactive Thymocytes Differentiate into Regulatory Versus Effector CD4+ T Cells After Avoiding Clonal Deletion. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprouse, M.L.; Shevchenko, I.; Scavuzzo, M.A.; Joseph, F.; Lee, T.; Blum, S.; Borowiak, M.; Bettini, M.L.; Bettini, M. Cutting Edge: Low-Affinity TCRs Support Regulatory T Cell Function in Autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Lee, G.R. Transcriptional Regulation and Development of Regulatory T Cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, e456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, M.F.; Hinks, T.S.C. MAIT Cells and the Microbiome. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1127588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salou, M.; Legoux, F.; Lantz, O. MAIT Cell Development in Mice and Humans. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 130, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, L.C.; Amini, A.; FitzPatrick, M.E.B.; Lett, M.J.; Hess, G.F.; Filipowicz Sinnreich, M.; Provine, N.M.; Klenerman, P. Single-Cell Analysis of Human MAIT Cell Transcriptional, Functional and Clonal Diversity. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, H.F.; Gherardin, N.A.; Enders, A.; Loh, L.; Mackay, L.K.; Almeida, C.F.; Russ, B.E.; Nold-Petry, C.A.; Nold, M.F.; Bedoui, S.; et al. A Three-Stage Intrathymic Development Pathway for the Mucosal-Associated Invariant T Cell Lineage. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 1300–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjer-Nielsen, L.; Patel, O.; Corbett, A.; Le Nours, J.; Meehan, B.; Liu, L.; Bhati, M.; Chen, Z.; Kostenko, L.; Reantragoon, R.; et al. MR1 Presents Microbial Vitamin B Metabolites to MAIT Cells. Nature 2012, 491, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, W.; Mayall, J.R.; Xu, W.; Johansen, M.D.; Patton, T.; Lim, X.Y.; Galvao, I.; Howson, L.J.; Brown, A.C.; Haw, T.J.; et al. Cigarette Smoke Components Modulate the MR1-MAIT Axis. J. Exp. Med. 2025, 222, e20240896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drashansky, T.T.; Helm, E.Y.; Curkovic, N.; Cooper, J.; Cheng, P.; Chen, X.; Gautam, N.; Meng, L.; Kwiatkowski, A.J.; Collins, W.O.; et al. BCL11B Is Positioned Upstream of PLZF and RORγt to Control Thymic Development of Mucosal-Associated Invariant T Cells and MAIT17 Program. iScience 2021, 24, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.J.; Kunze-Schumacher, H.; Imelmann, E.; Grewers, Z.; Osthues, T.; Krueger, A. MicroRNA miR-181a/b-1 Controls MAIT Cell Development. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2019, 97, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Liu, X.; Tomei, S.; Luo, M.; Skinner, J.P.; Berzins, S.P.; Naik, S.H.; Gray, D.H.D.; Chong, M.M.W. Distinct Subpopulations of DN1 Thymocytes Exhibit Preferential γδ T Lineage Potential. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1106652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Stadanlick, J.; Kappes, D.J.; Wiest, D.L. Towards a Molecular Understanding of the Differential Signals Regulating Alphabeta/Gammadelta T Lineage Choice. Semin. Immunol. 2010, 22, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallis, R.J.; Duke-Cohan, J.S.; Das, D.K.; Akitsu, A.; Luoma, A.M.; Banik, D.; Stephens, H.M.; Tetteh, P.W.; Castro, C.D.; Krahnke, S.; et al. Molecular Design of the γδT Cell Receptor Ectodomain Encodes Biologically Fit Ligand Recognition in the Absence of Mechanosensing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023050118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laky, K.; Lefrançois, L.; von Freeden-Jeffry, U.; Murray, R.; Puddington, L. The Role of IL-7 in Thymic and Extrathymic Development of TCR Gamma Delta Cells. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz Pérez, M.; Vandenabeele, P.; Tougaard, P. The Thymus Road to a T Cell: Migration, Selection, and Atrophy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1443910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahl, S.P.; Contreras, A.V.; Verma, A.; Qiu, X.; Harly, C.; Radtke, F.; Zúñiga-Pflücker, J.C.; Murre, C.; Xue, H.-H.; Sen, J.M.; et al. The E Protein-TCF1 Axis Controls γδ T Cell Development and Effector Fate. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, C.; Ma, S.; Ma, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhu, J.; Yang, D. The Protective Role of Tissue-Resident Interleukin 17A-Producing Gamma Delta T Cells in Mycobacterium Leprae Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 961405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venken, K.; Jacques, P.; Mortier, C.; Labadia, M.E.; Decruy, T.; Coudenys, J.; Hoyt, K.; Wayne, A.L.; Hughes, R.; Turner, M.; et al. RORγt Inhibition Selectively Targets IL-17 Producing iNKT and γδ-T Cells Enriched in Spondyloarthritis Patients. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.L.Y.; Lee, C.R.; Thompson, P.K.; Wiest, D.L.; Anderson, M.K.; Zúñiga-Pflücker, J.C. Ontogenic timing, T cell receptor signal strength, and Notch signaling direct γδ T cell functional differentiation in vivo. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karner, K.H.; Menon, M.P.; Inamdar, K.V.; Carey, J.L. Post-Transplant CD4+ Non-Cytotoxic γδ T Cell Lymphoma With Lymph Node Involvement. J. Hematop. 2018, 11, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Ohtsuka, K.; Watanabe, H.; Asakura, H.; Abo, T. Detailed characterization of gamma delta T cells within the organs in mice: Classification into three groups. Immunology 1993, 80, 380–387. [Google Scholar]

- Born, W.K.; Kemal Aydintug, M.; O’Brien, R.L. Diversity of γδ T-Cell Antigens. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2013, 10, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.L.; von Borstel, A.; Taher, T.E.; Syrimi, E.; Taylor, G.S.; Sharif, M.; Rossjohn, J.; Remmerswaal, E.B.; Bemelman, F.J.; Braga, F.A.V.; et al. Transcriptional Profiling of Human Vδ1 T Cells Reveals a Pathogen-Driven Adaptive Differentiation Program. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Bu, X.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Y. Research Progress on V Delta 1+ T Cells and Their Effect on Pathogen Infection. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ji, H.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, H.; Ma, B.; Qi, H. Profiles, Distribution, and Functions of Gamma Delta T Cells in Ocular Surface Homeostasis and Diseases. Front. Biosci. 2024, 29, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerich, L.; Bangen, J.M.; Govaere, O.; Zimmermann, H.W.; Gassler, N.; Huss, S.; Liedtke, C.; Prinz, I.; Lira, S.A.; Luedde, T.; et al. Chemokine Receptor CCR6-Dependent Accumulation of γδ T Cells in Injured Liver Restricts Hepatic Inflammation and Fibrosis. Hepatology 2014, 59, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Lu, N.; Zhang, C. Murine CXCR3+CXCR6+γδT Cells Reside in the Liver and Provide Protection Against HBV Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 757379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyerich, S.; Eyerich, K.; Cavani, A.; Schmidt-Weber, C. IL-17 and IL-22: Siblings, Not Twins. Trends Immunol. 2010, 31, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingoni, A.; Ardolino, M.; Santoni, A.; Cerboni, C. NKG2D and DNAM-1 Activating Receptors and Their Ligands in NK-T Cell Interactions: Role in the NK Cell-Mediated Negative Regulation of T Cell Responses. Front. Immunol. 2013, 3, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugai, S.; Yoshikawa, T.; Iwama, T.; Tsuchiya, N.; Ueda, N.; Fujinami, N.; Shimomura, M.; Zhang, R.; Kaneko, S.; Uemura, Y.; et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Sensitivity to Vγ9Vδ2 T Lymphocyte-Mediated Killing Is Increased by Zoledronate. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 48, 1794–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, X.; Guo, Y.; Chen, H.; Xu, C.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H.; Cui, L.; Ba, D.; He, W. Antigen Specificity of Gammadelta T Cells Depends Primarily on the Flanking Sequences of CDR3δ. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 27449–27455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieppo, P.; Papadopoulou, M.; Gatti, D.; McGovern, N.; Chan, J.K.Y.; Gosselin, F.; Goetgeluk, G.; Weening, K.; Ma, L.; Dauby, N.; et al. The Human Fetal Thymus Generates Invariant Effector γδ T Cells. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20190580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, W.; Huang, B.; Chi, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Su, Q.; Zhou, Q. Structures of Human γδ T Cell Receptor-CD3 Complex. Nature 2024, 630, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, H.; Chen, T.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, W.; Lin, N.; Yu, X.; Lou, Y.; Li, B.; Yinwang, E.; et al. Human γδ T Cells Induce CD8+ T Cell Antitumor Responses via Antigen-Presenting Effect Through HSP90-MyD88-Mediated Activation of JNK. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 1803–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatzel, A.; Wesch, D.; Schiemann, F.; Brandt, E.; Janssen, O.; Kabelitz, D. Patterns of Chemokine Receptor Expression on Peripheral Blood Gamma Delta T Lymphocytes: Strong Expression of CCR5 Is a Selective Feature of V Delta 2/V Gamma 9 Gamma Delta T Cells. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 4920–4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, A.; Carosio, R.; Fenoglio, D.; Brenci, S.; Murdaca, G.; Setti, M.; Indiveri, F.; Scabini, S.; Ferrero, E.; Zocchi, M.R. Migration of V Delta 1 and V Delta 2 T Cells in Response to CXCR3 and CXCR4 Ligands in Healthy Donors and HIV-1-Infected Patients: Competition by HIV-1 Tat. Blood 2004, 103, 2205–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Niu, C.; Cui, J. Gamma-Delta (γδ) T Cells: Friend or Foe in Cancer Development? J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sant, S.; Jenkins, M.R.; Dash, P.; Watson, K.A.; Wang, Z.; Pizzolla, A.; Koutsakos, M.; Nguyen, T.H.; Lappas, M.; Crowe, J.; et al. Human γδ T-Cell Receptor Repertoire Is Shaped by Influenza Viruses, Age and Tissue Compartmentalisation. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2019, 8, e1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Yin, W.; Chen, W. Mathematical Models of TCR Initial Triggering. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1411614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksic, M.; Dushek, O.; Zhang, H.; Shenderov, E.; Chen, J.L.; Cerundolo, V.; Coombs, D.; van der Merwe, P.A. Dependence of T Cell Antigen Recognition on T Cell Receptor-Peptide MHC Confinement Time. Immunity 2010, 32, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasinghe, S.D.; Peres, N.G.; Goyette, J.; Gaus, K. Biomechanics of T Cell Dysfunctions in Chronic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 600829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, M.; Couturaud, B.; Carretero-Iglesia, L.; Duong, M.N.; Schmidt, J.; Monnot, G.C.; Romero, P.; Speiser, D.E.; Hebeisen, M.; Rufer, N. TCR-Ligand Dissociation Rate Is a Robust and Stable Biomarker of CD8+ T Cell Potency. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e92570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, X.; Ma, W.; Duan, J.; Xue, J.; Yang, H.; et al. Phosphoantigens Glue Butyrophilin 3A1 and 2A1 to Activate Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells. Nature 2023, 621, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, W.L.; Shah, N.H.; Ahsan, N.; Horkova, V.; Stepanek, O.; Salomon, A.R.; Kuriyan, J.; Weiss, A. Lck Promotes Zap70-Dependent LAT Phosphorylation by Bridging Zap70 to LAT. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 733–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wither, M.J.; White, W.L.; Pendyala, S.; Leanza, P.J.; Fowler, D.; Kueh, H.Y. Antigen Perception in T Cells by Long-Term Erk and NFAT Signaling Dynamics. bioRxiv 2023, Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, C.R.; Vantourout, P.; Salim, M.; Zlatareva, I.; Melandri, D.; Zanardo, L.; George, R.; Kjaer, S.; Jeeves, M.; Mohammed, F.; et al. Butyrophilin-Like 3 Directly Binds a Human Vγ4+ T Cell Receptor Using a Modality Distinct from Clonally-Restricted Antigen. Immunity 2019, 51, 813–825.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, B.; Chen, J.Y.; Han, P.; Rufner, K.M.; Goularte, O.D.; Kaye, J. TOX: An HMG Box Protein Implicated in the Regulation of Thymocyte Selection. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.L.; Schilling, M.M.; Cho, S.H.; Lee, K.; Wei, M.; Aditi; Boothby, M. STAT4 and T-bet Are Required for the Plasticity of IFN-γ Expression Across Th2 Ontogeny and Influence Changes in Ifng Promoter DNA Methylation. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, C.; Yang, D.; Zhou, J.; Dong, H.; Wei, Z.; Xu, S.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; et al. STAT3 and SOX-5 Induce BRG1-Mediated Chromatin Remodeling of RORCE2 in Th17 Cells. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S.; Amasaki, Y.; Miyatake, S.; Arai, N.; Iwata, M. Successive Expression and Activation of NFAT Family Members During Thymocyte Differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 14708–14716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, D.; Gómez, M.; Viedma, F.; Esplugues, E.; Gordón-Alonso, M.; García-López, M.A.; de la Fuente, H.; Martínez-A, C.; Lauzurica, P.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. CD69 Down-Regulates Autoimmune Reactivity Through Active Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Production in Collagen-Induced Arthritis. J. Clin. Investg. 2003, 112, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, P.J.; Alegre, M.L.; Reiner, S.L.; Thompson, C.B. Impaired Negative Selection in CD28-Deficient Mice. Cell. Immunol. 1998, 187, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimova, T.; Ge, G.; Golovina, T.; Mikheeva, T.; Wang, L.; Riley, J.L.; Hancock, W.W. Histone/Protein Deacetylase Inhibitors Increase Suppressive Functions of Human FOXP3+ Tregs. Clin. Immunol. 2010, 136, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfar, R.; Napoleon, J.V.; Shahriar, I.; Finnell, R.; Walchle, C.; Johnson, A.; Low, P.S. Selective Reprogramming of Regulatory T Cells in Solid Tumors Can Strongly Enhance or Inhibit Tumor Growth. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1274199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thien, C.B.; Langdon, W.Y. c-Cbl and Cbl-b Ubiquitin Ligases: Substrate Diversity and the Negative Regulation of Signalling Responses. Biochem. J. 2005, 391, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakov, N.; Altman, A. PKC-Theta-Mediated Signal Delivery from the TCR/CD28 Surface Receptors. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehn, D.; Lee, S.; Bevan, M. Complete but Curtailed T-Cell Response to Very Low-Affinity Antigen. Nature 2009, 458, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Fichtner, A.S.; Bruni, E.; Odak, I.; Sandrock, I.; Bubke, A.; Borchers, A.; Schultze-Florey, C.; Koenecke, C.; Förster, R.; et al. A Fetal Wave of Human Type 3 Effector γδ Cells with Restricted TCR Diversity Persists into Adulthood. Sci. Immunol. 2021, 6, eabf0125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.F. Immunological Function of the Thymus. Lancet 1961, 278, 748–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Henze, L.; Casar, C.; Schwinge, D.; Schramm, C.; Fuss, J.; Tan, L.; Prinz, I. Human γδ T Cell Identification from Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Datasets by Modular TCR Expression. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2023, 114, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.M.; Stultz, R.; Bonde, S.; Zavazava, N. Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived T Cells Induce Lethal Graft-Versus-Host Disease and Reject Allogenic Skin Grafts Upon Thymic Selection. Am. J. Transpl. 2012, 12, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyao, T.; Miyauchi, M.; Kelly, S.T.; Terooatea, T.W.; Ishikawa, T.; Oh, E.; Hirai, S.; Horie, K.; Takakura, Y.; Ohki, H.; et al. Integrative Analysis of scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq Revealed Transit-Amplifying Thymic Epithelial Cells Expressing Autoimmune Regulator. elife 2022, 11, e73998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, I.N.; Chiang, B.L.; Lou, K.L.; Huang, P.T.; Yao, C.C.; Wang, J.S.; Lin, L.-D.; Jeng, J.-H.; Chang, B.-E. Cloning, Expression and Characterization of CCL21 and CCL25 Chemokines in Zebrafish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2012, 38, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thome, J.J.; Grinshpun, B.; Kumar, B.V.; Kubota, M.; Ohmura, Y.; Lerner, H.; Sempowski, G.D.; Shen, Y.; Farber, D.L. Longterm Maintenance of Human Naive T Cells Through in Situ Homeostasis in Lymphoid Tissue Sites. Sci. Immunol. 2016, 1, eaah6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weist, B.M.; Kurd, N.; Boussier, J.; Chan, S.W.; Robey, E.A. Thymic Regulatory T Cell Niche Size Is Dictated by Limiting IL-2 from Antigen-Bearing Dendritic Cells and Feedback Competition. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, S.A.; Armitage, L.H.; Morton, J.J.; Alzofon, N.; Handler, D.; Kelly, G.; Homann, D.; Jimeno, A.; Russ, H.A. Generation of Functional Thymic Organoids from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2023, 18, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Tissue-Engineered Artificial Human Thymus from Human iPSCs to Study T Cell Immunity. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 1191–1192. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montel-Hagen, A.; Seet, C.S.; Li, S.; Chick, B.; Zhu, Y.; Chang, P.; Tsai, S.; Sun, V.; Lopez, S.; Chen, H.-C.; et al. Organoid-Induced Differentiation of Conventional T Cells from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 24, 376–389.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Nicol, S.A.; Suen, A.Y.; Baldwin, T.A. Examination of Thymic Positive and Negative Selection by Flow Cytometry. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 68, 4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaglia, F.; Ryvkin, A.; Greenstein, E.; Reich-Zeliger, S.; Chain, B.; Mora, T.; Walczak, A.M.; Friedman, N. Quantifying Changes in the T Cell Receptor Repertoire During Thymic Development. eLife 2023, 12, e81622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, M.; Canté-Barrett, K.; van den Akker, E.B.; Moretti, F.A.; Kiełbasa, S.M.; Vloemans, S.A.; Garcia-Perez, L.; Teodosio, C.; van Dongen, J.J.M.; Pike-Overzet, K.; et al. Single-Cell Immune Profiling Reveals Thymus-Seeding Populations, T Cell Commitment, and Multilineage Development in the Human Thymus. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eade0182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadovskaya, V.A.; Sennikov, S.V.; Ostanin, A.A.; Seledtsova, G.V.; Silkov, A.N.; Kozlov, V.A. Ontogenetic Features of the Expression of mRNA Isoforms for Leukemia-Inhibitory Factor in Human Fetal Tissues and Mononuclear Cells. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2009, 147, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J.; Park, J.E.; Ha, V.; Luong, A.; Branciamore, S.; Rodin, A.S.; Gogoshin, G.; Li, F.; Loh, Y.E.; Camacho, V.; et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Mapping of Human Thymopoiesis Reveals Lineage Specification Trajectories and a Commitment Spectrum in T Cell Development. Immunity 2020, 52, 1105–1118.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskowitz, D.M.; Zhang, D.W.; Hu, B.; Le Saux, S.; Yanes, R.E.; Ye, Z.; Buenrostro, J.D.; Weyand, C.M.; Greenleaf, W.J.; Goronzy, J.J. Epigenomics of Human CD8 T Cell Differentiation and Aging. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2, eaag0192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Qin, Y.; Lu, L.; Zheng, M. Transcriptional Regulation of Early T-Lymphocyte Development in Thymus. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 884569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Nojima, S.; Koizumi, N.; Okuzaki, D.; Funaki, S.; Shintani, Y.; Ohkura, N.; Morii, E.; Okuno, T.; Mochizuki, H. Spatial Transcriptomics Elucidates Medulla Niche Supporting Germinal Center Response in Myasthenia Gravis-Associated Thymoma. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojika, M.; Ishii, G.; Yoshida, J.; Nishimura, M.; Hishida, T.; Ota, S.J.; Murata, Y.; Nagai, K.; Ochiai, A. Immunohistochemical Differential Diagnosis Between Thymic Carcinoma and Type B3 Thymoma: Diagnostic Utility of Hypoxic Marker, GLUT-1, in Thymic Epithelial Neoplasms. Mod. Pathol. 2009, 22, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janardhan, K.S.; Jensen, H.; Clayton, N.P.; Herbert, R.A. Immunohistochemistry in Investigative and Toxicologic Pathology. Toxicol. Pathol. 2018, 46, 488–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansenne, I.; Louis, C.; Martens, H.; Dorban, G.; Charlet-Renard, C.; Peterson, P.; Geenen, V. Aire and Foxp3 Expression in a Particular Microenvironment for T Cell Differentiation. Neuroimmunomodulation 2009, 16, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Matsuno, Y.; Kunitoh, H.; Maeshima, A.; Asamura, H.; Tsuchiya, R. Immunohistochemical KIT (CD117) Expression in Thymic Epithelial Tumors. Chest 2005, 128, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, M.; Nagakubo, D.; Kanzler, B.; Avilov, S.; Krauth, B.; Happe, C.; Swann, J.B.; Nusser, A.; Boehm, T. Fundamental Parameters of the Developing Thymic Epithelium in the Mouse. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Nicholls, P.K.; Yin, C.; Kelman, K.; Yuan, Q.; Greene, W.K.; Shi, Z.; Ma, B. Immunofluorescent Localization of Non-Myelinating Schwann Cells and Their Interactions With Immune Cells in Mouse Thymus. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2018, 66, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, J.N.; Ehrlich, L.I. Analysis of Thymocyte Migration, Cellular Interactions, and Activation by Multiphoton Fluorescence Microscopy of Live Thymic Slices. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1591, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzal, D.; Gradolatto, A.; Truffault, F.; Bismuth, J.; Berrih-Aknin, S. Human Thymus Medullary Epithelial Cells Promote Regulatory T-Cell Generation by Stimulating Interleukin-2 Production via ICOS Ligand. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pircher, H.; Pinschewer, D.D.; Boehm, T. MHC I Tetramer Staining Tends to Overestimate the Number of Functionally Relevant Self-Reactive CD8 T Cells in the Preimmune Repertoire. Eur. J. Immunol. 2023, 53, e2350402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dileepan, T.; Malhotra, D.; Kotov, D.I.; Kolawole, E.M.; Krueger, P.D.; Evavold, B.D.; Jenkins, M.K. MHC Class II Tetramers Engineered for Enhanced Binding to CD4 Improve Detection of Antigen-Specific T Cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, R.J.; Andargachew, R.; Martinez, H.A.; Evavold, B.D. Low-Affinity CD4+ T Cells Are Major Responders in the Primary Immune Response. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, C.A.; Choi, S.; Livak, F.; Zhao, B.; Mitra, A.; Love, P.E.; Singh, N.J. CD5 Dynamically Calibrates Basal NF-κB Signaling in T Cells During Thymic Development and Peripheral Activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14342–14353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giam, M.; Mintern, J.D.; Rautureau, G.J.; Hinds, M.G.; Strasser, A.; Bouillet, P. Detection of Bcl-2 Family Member Bcl-G in Mouse Tissues Using New Monoclonal Antibodies. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, J.A.; Brondstetter, T.I.; English, C.A.; Lee, H.E.; Virts, E.L.; Thoman, M.L. IL-7 Gene Therapy in Aging Restores Early Thymopoiesis Without Reversing Involution. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 4867–4874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchill, M.A.; Goetz, C.A.; Prlic, M.; O’Neil, J.J.; Harmon, I.R.; Bensinger, S.J.; Turka, L.A.; Brennan, P.; Jameson, S.C.; Farrar, M.A. Distinct Effects of STAT5 Activation on CD4+ and CD8+ T Cell Homeostasis: Development of CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T Cells Versus CD8+ Memory T Cells. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 5853–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmers, S.; Schizas, M.; Azizi, E.; Dikiy, S.; Zhong, Y.; Feng, Y.; Altan-Bonnet, G.; Rudensky, A.Y. IL-2 Production by Self-Reactive CD4 Thymocytes Scales Regulatory T Cell Generation in the Thymus. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 2466–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malin, S.; McManus, S.; Cobaleda, C.; Novatchkova, M.; Delogu, A.; Bouillet, P.; Strasser, A.; Busslinger, M. Role of STAT5 in Controlling Cell Survival and Immunoglobulin Gene Recombination During pro-B Cell Development. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Affinity Level | KD Range | Outcomes/Markers | Signaling/Mechanisms | Examples/Type of Cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (Strong Signal) | KD < 1 μM | αβ T cells | Clonal deletion/apoptosis (Bim/Nur77); | αβ T cells | Lack costimulation → anergy (Cbl-b/GRAIL) | αβ T cells | Autoreactive αβ T cells |

| Treg induction (FOXP3/CD25) | Prolonged ERK/NFAT/AP-1 | high-affinity Tregs | |||||

| γδ T cells | γδ selection (PLZF/Sox13, Bim) | γδ T cells | Modulation by BTNL and activation TOX | γδ T cells | Vδ1+ T cells phosphoantigen response | ||

| Intermediate (Survival) | 1–10 μM | αβ T cells | Positive selection → SP (CD69+) | αβ T cells | LCK/ZAP70 → ThPOK/Runx3 balance | αβ T cells | Naive CD4+/CD8+ |

| migration (CCR7↑) | metabolic shift (mTOR) | low Treg suppression | |||||

| γδ T cells | γδ selection (PLZF/Sox13, Bim) | γδ T cells | Activation RORγt and Notch pathway | γδ T cells | NK, Th, Th17 and Vδ2+ | ||

| Low (Weak Signal, anergy) | >10 μM | αβ T cells | Anergy after Negative selection (NR4A/Nur77) | αβ T cells | HDAC/EZH2 suppression | αβ T cells | Naive/low-affinity Aβ; anergic clones |

| memory potential Aβ T cells | FOXO1/Klf2 (CCR7/S1PR1 migration) | Tolerogenic Aβ T cells | |||||

| γδ T cells | Death by neglect | γδ T cells | Activation RANTES and CXCR3 | γδ T cells | Naive/low-affinity γδ; anergic clones | ||

| γδ selection (PLZF) | Vδ2+ phosphoantigen presentation | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bulygin, A.; Golikova, E.; Sennikov, S. Development of αβ and γδ T Cells in the Thymus and Methods of Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11939. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411939

Bulygin A, Golikova E, Sennikov S. Development of αβ and γδ T Cells in the Thymus and Methods of Analysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11939. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411939

Chicago/Turabian StyleBulygin, Aleksey, Elena Golikova, and Sergey Sennikov. 2025. "Development of αβ and γδ T Cells in the Thymus and Methods of Analysis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11939. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411939

APA StyleBulygin, A., Golikova, E., & Sennikov, S. (2025). Development of αβ and γδ T Cells in the Thymus and Methods of Analysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11939. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411939