Alternative Splicing-Mediated Resistance to Antibody-Based Therapies: Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

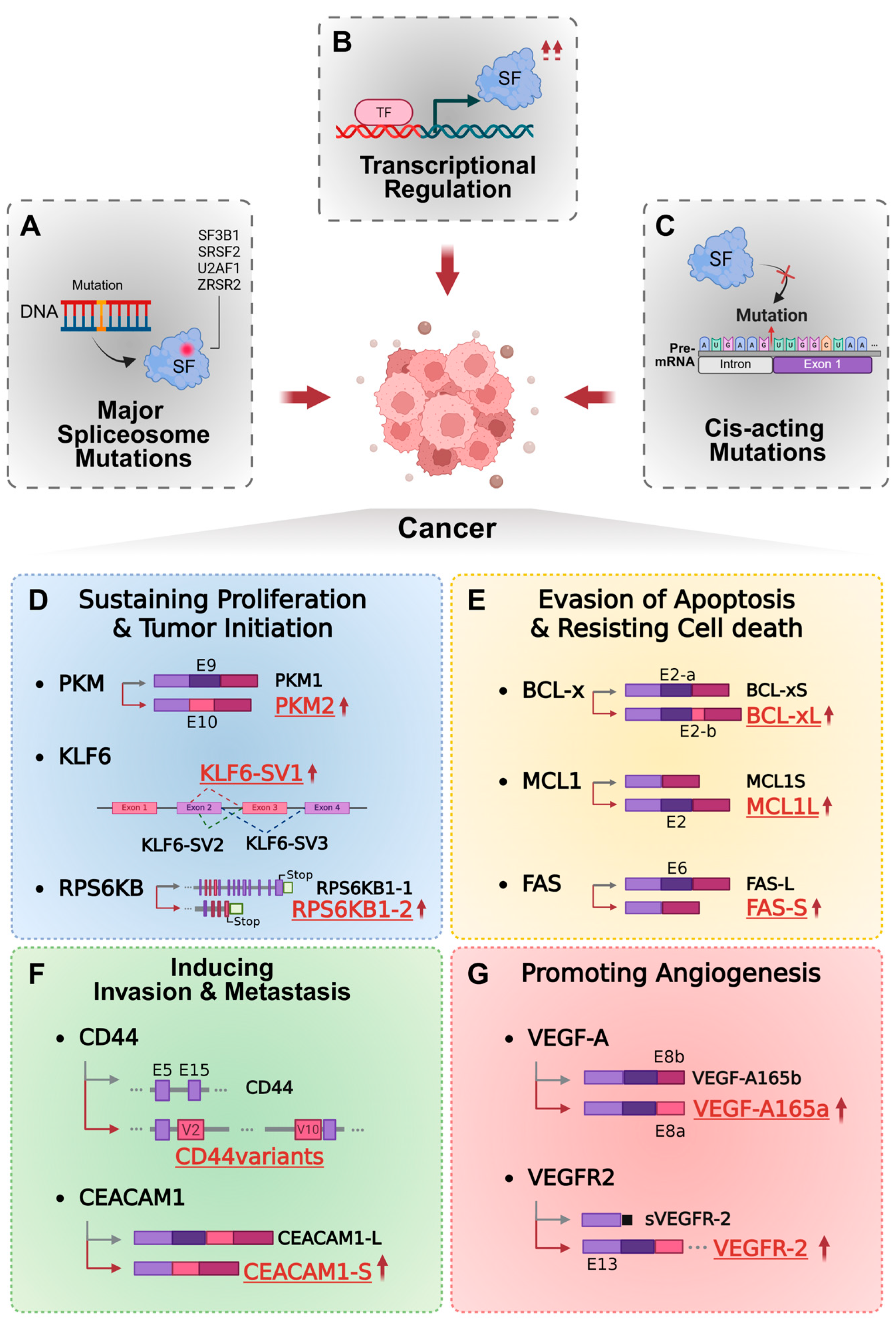

2. Mechanism of Aberrant Regulation of RNA Splicing in Cancer

- (1)

- Mutations in core spliceosomal components

- (2)

- Altered expression of splicing factors

- (3)

- Cis-acting mutations within RNA regulatory elements

3. Oncogenic Functions of Aberrant Alternative Splicing Isoforms

3.1. Tumor Growth and Proliferation

3.2. Apoptosis Evasion (Resisting Cell Death)

3.3. Invasion and Metastasis

3.4. Tumor Angiogenesis

4. Antibody-Based Therapeutics and the Impact of RNA Splicing on Therapeutic Resistance

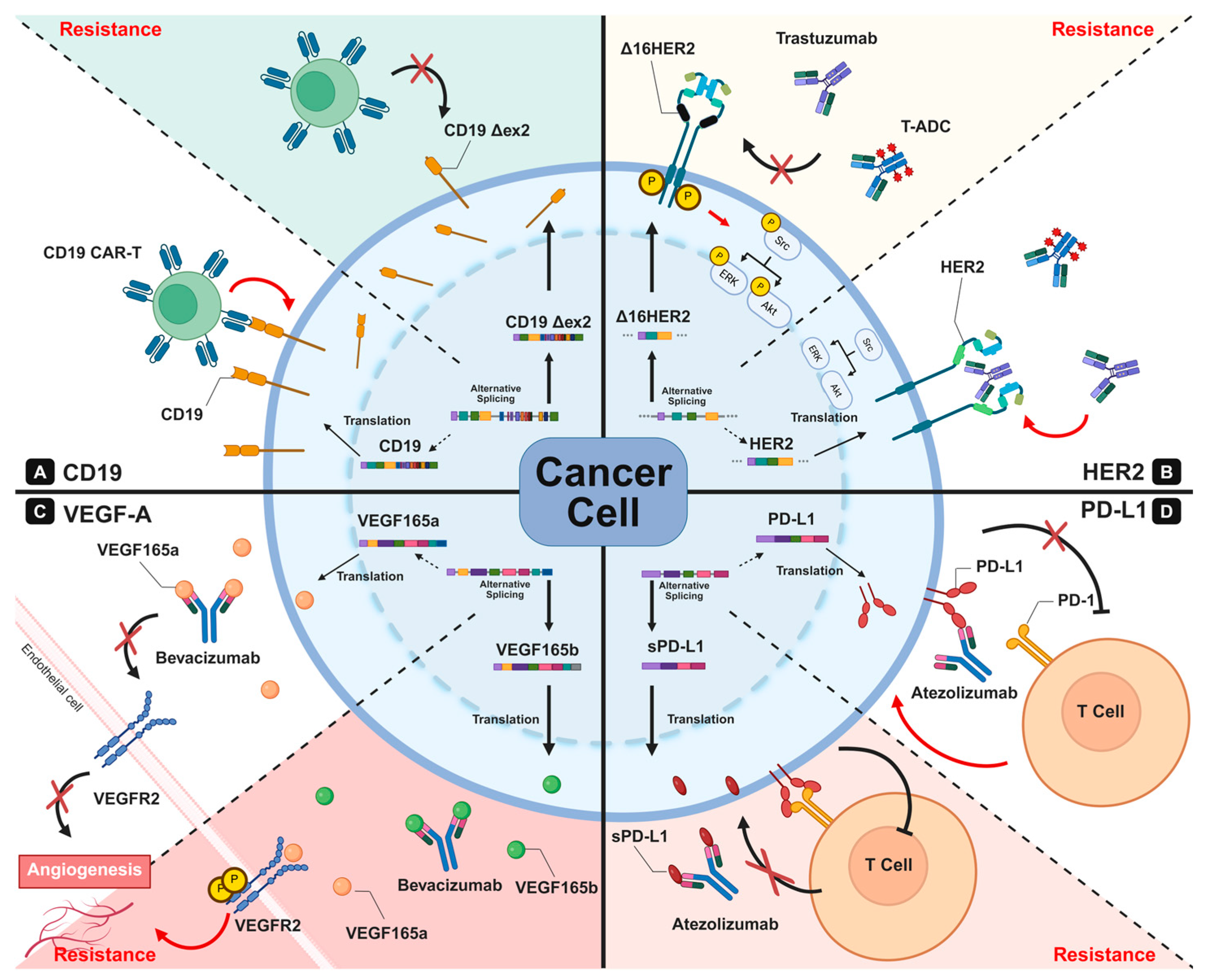

4.1. Alternative Splicing as a Driver of Antigenic Plasticity

- (1)

- Loss of Extracellular Epitopes Through Exon Skipping

- (2)

- Structural Remodeling of Receptor Conformation

- (3)

- Generation of Soluble Decoy Isoforms

- (4)

- Signaling Rewiring Through Isoform Switching

4.2. Target-Specific Manifestations of Splicing-Mediated Resistance

4.2.1. CD19/CD22: Exon Skipping-Mediated Antigen Loss in B-Cell Malignancies

- (1)

- Biological Roles of CD19 and CD22

- (2)

- Therapeutic Outcomes and Resistance Dynamics

- (3)

- RNA Splicing-Mediated Mechanisms of Resistance

4.2.2. CD20: Splicing-Related Modulation of Antigen Density and Resistance to Anti-CD20 Therapy

- (1)

- Biological Roles of CD20

- (2)

- Therapeutic Outcomes and Resistance Dynamics

- (3)

- RNA Splicing-Mediated Mechanisms of Resistance

4.2.3. ERBB Family Receptors: Divergent Splicing-Driven Resistance

EGFR: Alternative Splicing and Resistance to Anti-EGFR Therapy

- (1)

- Biological Roles of EGFR

- (2)

- Therapeutic Outcomes and Resistance Dynamics

- (3)

- RNA Splicing-Mediated Mechanisms of Resistance

HER2: Exon 16 Skipping and Receptor Rewiring

- (1)

- Biological Roles of HER2

- (2)

- Therapeutic Outcomes and Resistance Dynamics

- (3)

- RNA Splicing-Mediated Mechanisms of Resistance

4.2.4. VEGF: Isoform Switching and Soluble Ligand Decoys

- (1)

- Biological Roles of VEGF

- (2)

- Therapeutic Outcomes and Resistance Dynamics

- (3)

- RNA Splicing-Mediated Mechanisms of Resistance

4.2.5. PD-1/PD-L1: Soluble Isoforms and Immune Checkpoint Blockade Resistance

- (1)

- Biological Roles of PD-1 and PD-L1

- (2)

- Therapeutic Outcomes and Resistance Dynamics

- (3)

- RNA Splicing-Mediated Mechanisms of Resistance

5. Advanced Strategies to Counter Aberrant Regulation of RNA Splicing in Cancer

5.1. Comprehensive Mapping of Cancer Splicing Landscapes

5.2. Integrating Splicing Signatures into Diagnostics and Patient Monitoring

5.3. Therapeutic Targeting of Splicing Regulators

5.4. Clinical Applications of Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) and RNA Editing

5.5. Development of Isoform-Selective Antibodies and ADCs

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABBREVIATION | FULL TERM |

| ADC | Antibody–Drug Conjugate |

| ADCC | Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity |

| ADCP | Antibody-Dependent Cellular Phagocytosis |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| AS | Alternative Splicing |

| ASCANCER | Alternative Splicing in Cancer Atlas |

| ASO | Antisense Oligonucleotide |

| B-ALL | B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia |

| BCL2L1 | BCL2-Like 1 |

| BCL-XL | BCL2-like 1 long isoform |

| BCL-XS | BCL2-like 1 short isoform |

| BCR | B-cell Receptor |

| BPS | Branch Point Site |

| BSAB | Bispecific Antibody |

| CAR | Chimeric Antigen Receptor |

| CAR-T | Chimeric Antigen Receptor T cell |

| CD | Cluster of Differentiation |

| CDC | Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity |

| CEACAM1 | Carcinoembryonic Antigen-Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| CEACAM1-S | CEACAM1 short isoform |

| CLEOPATRA | CLinical Evaluation Of Pertuzumab And TRAstuzumab |

| CLK1 | CDC-like Kinase 1 |

| CLL | Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia |

| CR | Complete Remission |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte-Associated Protein 4 |

| DAR | Drug-to-Antibody Ratio |

| DDX5 | DEAD-box Helicase 5 |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR/ERBB1) |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition |

| ERBB | Erythroblastic Leukemia Viral Oncogene Homolog (Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Family) |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| ESRP1 | Epithelial Splicing Regulatory Protein 1 |

| ESS | Exonic Splicing Silencer |

| FAB | Fragment Antigen Binding |

| FAS | Fas Cell Surface Death Receptor |

| FC | Fragment crystallizable |

| FLT-1 | Fms-like Tyrosine Kinase-1 (also called VEGFR1) |

| FLT-4 | Fms-like Tyrosine Kinase-4 (also called VEGFR3) |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| HER3 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 3 |

| HER4 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 4 |

| HNRNP H1 | Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein H1 |

| HNRNPK | Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein K |

| HNSCC | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| ITIM | Immunoreceptor Tyrosine-Based Inhibitory Motif |

| KDR | Kinase-Insert Domain Receptor (VEGFR2) |

| KLF6 | Kruppel-like factor 6 |

| KLF6-SV1 | Kruppel-like factor 6 splice variant 1 |

| LYN | Src Family Tyrosine Kinase Lyn |

| MAB | Monoclonal Antibody |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MATR3 | Matrin 3 |

| MCL1 | Myeloid Cell Leukemia 1 |

| MCL1L | Myeloid cell leukemia 1, long isoform |

| MCL1S | Myeloid cell leukemia 1, short isoform |

| MRNA | messenger RNA |

| MS4A1 | Membrane-Spanning 4-Domains A1 (CD20 gene) |

| MTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| MTORC1 | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 |

| MVEGFR2 | Membrane VEGFR2 |

| NFAT | Nuclear Factor of Activated T cells |

| NHL | Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma |

| NSCLC | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PDCD1 | PD-1 gene |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PD-L2 | Programmed Death-Ligand 2 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase |

| PKM | Pyruvate Kinase M |

| PKM1 | Pyruvate Kinase isozymes M1 |

| PKM2 | Pyruvate Kinase isozymes M2 |

| PLCγ | Phospholipase C-gamma |

| PLGF | Placental Growth Factor |

| PRE-MRNA | precursor messenger RNA |

| PTBP1 | Polypyrimidine Tract Binding Protein 1 |

| RHUPH20 | Recombinant Human Hyaluronidase PH20 |

| RPS6KB1 | Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase Beta1 |

| RPS6KB1-1 | RPS6KB1 alternative splice variant 1 |

| RPS6KB1-2 | RPS6KB1 alternative splice variant 2 |

| SC | Subcutaneous |

| SCFV | Single-Chain Variable Fragment |

| SF | Splicing factor |

| SF3B1 | Splicing factor 3B subunit 1 |

| SHP2 | Src Homology 2-Containing Phosphatase 2 |

| SMA | Spinal Muscular Atrophy |

| SPD-1 | Soluble PD-1 |

| SPD-L1 | Soluble PD-L1 |

| SR | Serine/Arginine-rich |

| SRC | Sarcoma |

| SRPK1 | Serine/arginine-Rich Splicing Factor (SRSF) protein kinase 1 |

| SRPK2 | Serine/arginine-Rich Splicing Factor (SRSF) protein kinase 2 |

| SRSF1 | Serine/Arginine-Rich Splicing Factor 1 |

| SRSF2 | Serine/Arginine-Rich Splicing Factor 2 |

| SRSF3 | Serine/Arginine-Rich Splicing Factor 3 |

| SRSF5 | Serine/Arginine-Rich Splicing Factor 5 |

| SRSF7 | Serine/Arginine-Rich Splicing Factor 7 |

| SVEGFR2 | Soluble VEGFR2 |

| TCR | T Cell Receptor |

| T-DM1 | Trastuzumab Emtansine |

| TDP-43 | TAR DNA-Binding Protein 43 |

| T-DXD | Trastuzumab Deruxtecan |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-β |

| TIA-1 | TIA1 cytotoxic granule associated RNA binding protein |

| TROP2 | Trophoblast Cell Surface Antigen 2 |

| U2 SNRNP | U2 Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein |

| U2AF1 | U2 Small Nuclear RNA Auxiliary Factor 1 |

| VAV | Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor Vav |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| VEGFA | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A |

| VEGFB | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor B |

| VEGFC | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor C |

| VEGFD | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor D |

| VEGFR1 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 |

| VEGFR2 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 |

| VEGFR3 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 |

| VHH | Variable domain of Heavy-chain-only antibody |

| ZRSR2 | Zinc finger CCCH-type RBM and serine/arginine rich 2 |

| Δ16HER2 | HER2 exon-16–deleted isoform |

| ΔEX2 | Exon 2-skipped isoform |

| ΔEX3 | Exon 3-skipped isoform |

| ΔEX5–6 | Exon 5–6-skipped isoform |

References

- Marasco, L.E.; Kornblihtt, A.R. The physiology of alternative splicing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choquet, K.; Patop, I.L.; Churchman, L.S. The regulation and function of post-transcriptional RNA splicing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2025, 26, 378–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Fang, L.; Wu, C. Alternative Splicing and Isoforms: From Mechanisms to Diseases. Genes 2022, 13, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponomarenko, E.A.; Poverennaya, E.V.; Ilgisonis, E.V.; Pyatnitskiy, M.A.; Kopylov, A.T.; Zgoda, V.G.; Lisitsa, A.V.; Archakov, A.I. The Size of the Human Proteome: The Width and Depth. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2016, 2016, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-S.; Pinto, S.M.; Getnet, D.; Nirujogi, R.S.; Manda, S.S.; Chaerkady, R.; Madugundu, A.K.; Kelkar, D.S.; Isserlin, R.; Jain, S.; et al. A draft map of the human proteome. Nature 2014, 509, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, T.W.; Graveley, B.R. Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature 2010, 463, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matera, A.G.; Wang, Z. A day in the life of the spliceosome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 108–121, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 294.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Shai, O.; Lee, L.J.; Frey, B.J.; Blencowe, B.J. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2008, 40, 1413–1415, Addendum in Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.T.; Sandberg, R.; Luo, S.; Khrebtukova, I.; Zhang, L.; Mayr, C.; Kingsmore, S.F.; Schroth, G.P.; Burge, C.B. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 2008, 456, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barash, Y.; Calarco, J.A.; Gao, W.; Pan, Q.; Wang, X.; Shai, O.; Blencowe, B.J.; Frey, B.J. Deciphering the splicing code. Nature 2010, 465, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejman, J.; Zieliński, G.; Gawda, P.; Lejman, M. Alternative Splicing Role in New Therapies of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Genes 2021, 12, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daguenet, E.; Dujardin, G.; Valcárcel, J. The pathogenicity of splicing defects: Mechanistic insights into pre- mRNA processing inform novel therapeutic approaches. Embo Rep. 2015, 16, 1640–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scotti, M.M.; Swanson, M.S. RNA mis-splicing in disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 17, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Rio, D.C. Mechanisms and Regulation of Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 291–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, M.; Bortfeldt, R.H.; Grützmann, K.; Schuster, S. Alternative splicing of mutually exclusive exons—A review. Biosystems 2013, 114, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, B.; Xu, Y.-M.; Li, J.; Huang, L.-F.; Lin, J.; Zhang, J.; Min, Q.-H.; Yang, W.-M.; et al. Mechanism of alternative splicing and its regulation. Biomed. Rep. 2014, 3, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, E.; Oltean, S. Alternative Splicing in Angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baralle, F.E.; Giudice, J. Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K.W. Regulation of Alternative Splicing by Signal Transduction Pathways. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007, 623, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.-P.; Lin, L.-J.; Liu, X.-M. Significance of alternative splicing in cancer cells. Chin. Med J. 2019, 133, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnal, S.C.; López-Oreja, I.; Valcárcel, J. Roles and mechanisms of alternative splicing in cancer — implications for care. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Qian, J.; Gu, C.; Yang, Y. Alternative splicing and cancer: A systematic review. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuranaga, Y.; Sugito, N.; Shinohara, H.; Tsujino, T.; Taniguchi, K.; Komura, K.; Ito, Y.; Soga, T.; Akao, Y. SRSF3, a Splicer of the PKM Gene, Regulates Cell Growth and Maintenance of Cancer-Specific Energy Metabolism in Colon Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, M.; Xu, L.; Suzuki, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; Sakamoto, H.; Uemura, H.; Yoshizawa, A.C.; Suzuki, Y.; Nakatsura, T.; Ishihama, Y.; et al. Aberrant splicing isoforms detected by full-length transcriptome sequencing as transcripts of potential neoantigens in non-small cell lung cancer. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, S.; Lynch, K.W. Alternative splicing and cancer: Insights, opportunities, and challenges from an expanding view of the transcriptome. Genes Dev. 2020, 34, 1005–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climente-González, H.; Porta-Pardo, E.; Godzik, A.; Eyras, E. The Functional Impact of Alternative Splicing in Cancer. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 2215–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanski, L.M.; Leclair, N.; Anczuków, O. Alternative-splicing defects in cancer: Splicing regulators and their downstream targets, guiding the way to novel cancer therapeutics. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2018, 9, e1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvinge, H.; Kim, E.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Bradley, R.K. RNA splicing factors as oncoproteins and tumour suppressors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurica, M.S.; Mesecar, A.; Heath, P.J.; Shi, W.; Nowak, T.; Stoddard, B.L. The allosteric regulation of pyruvate kinase by fructose-1,6-bisphosphate. Structure 1998, 6, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, C.J.; Chen, M.; Assanah, M.; Canoll, P.; Manley, J.L. HnRNP proteins controlled by c-Myc deregulate pyruvate kinase mRNA splicing in cancer. Nature 2009, 463, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Shi, X.-Y. Expression of pyruvate kinase M2 in human colorectal cancer and its prognostic value. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 11393–11399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DiFeo, A.; Martignetti, J.A.; Narla, G. The role of KLF6 and its splice variants in cancer therapy. Drug Resist. Updat. 2009, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Hur, V.; Denichenko, P.; Siegfried, Z.; Maimon, A.; Krainer, A.; Davidson, B.; Karni, R. S6K1 Alternative Splicing Modulates Its Oncogenic Activity and Regulates mTORC. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarrillo, R.; Wojtuszkiewicz, A.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Jansen, G.; Kaspers, G.J.; Giovannetti, E.; Cloos, J. The role of alternative splicing in cancer: From oncogenesis to drug resistance. Drug Resist. Updat. 2020, 53, 100728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minn, A.J.; Boise, L.H.; Thompson, C.B. Bcl-xS Antagonizes the Protective Effects of Bcl-xL. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 6306–6312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boise, L.H.; González-García, M.; Postema, C.E.; Ding, L.; Lindsten, T.; Turka, L.A.; Mao, X.; Nuñez, G.; Thompson, C.B. bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell 1993, 74, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aird, D.; Teng, T.; Huang, C.-L.; Pazolli, E.; Banka, D.; Cheung-Ong, K.; Eifert, C.; Furman, C.; Wu, Z.J.; Seiler, M.; et al. Sensitivity to splicing modulation of BCL2 family genes defines cancer therapeutic strategies for splicing modulators. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautrey, H.L.; Tyson-Capper, A.J. Regulation of Mcl-1 by SRSF1 and SRSF5 in Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, Y. SRSF7 knockdown promotes apoptosis of colon and lung cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 5545–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.L.; Reinke, L.M.; Damerow, M.S.; Perez, D.; Chodosh, L.A.; Yang, J.; Cheng, C. CD44 splice isoform switching in human and mouse epithelium is essential for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and breast cancer progression. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yae, T.; Tsuchihashi, K.; Ishimoto, T.; Motohara, T.; Yoshikawa, M.; Yoshida, G.J.; Wada, T.; Masuko, T.; Mogushi, K.; Tanaka, H.; et al. Alternative splicing of CD44 mRNA by ESRP1 enhances lung colonization of metastatic cancer cell. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.H.; Lin, Q.L.; Wei, J.; Huai, Y.L.; Wang, K.J.; Yan, H.Y. CD44v6 expression in patients with stage II or stage III sporadic colorectal cancer is superior to CD44 expression for predicting progression. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 692–701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Yokoyama, S.; Ueno, M.; Hayami, S.; Mitani, Y.; Takeuchi, A.; Shively, J.E.; Yamaue, H. CEACAM1 is associated with recurrence after hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastasis. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 220, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.J.; Bates, D.O. VEGF-A splicing: The key to anti-angiogenic therapeutics? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, D.G.; Amin, E.M.; Rennel, E.S.; Hoareau-Aveilla, C.; Gammons, M.; Damodoran, G.; Hagiwara, M.; Harper, S.J.; Woolard, J.; Ladomery, M.R.; et al. Regulation of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Splicing from Pro-angiogenic to Anti-angiogenic Isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 5532–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudria, A.; Faycal, C.A.; Jia, T.; Gout, S.; Keramidas, M.; Didier, C.; Lemaître, N.; Manet, S.; Coll, J.-L.; Toffart, A.-C.; et al. VEGF165b, a splice variant of VEGF-A, promotes lung tumor progression and escape from anti-angiogenic therapies through a β1 integrin/VEGFR autocrine loop. Oncogene 2018, 38, 1050–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlakovic, H.; Becker, J.; Albuquerque, R.; Wilting, J.; Ambati, J. Soluble VEGFR-2: An antilymphangiogenic variant of VEGF receptors. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1207, E7–E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, G.; Milstein, C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 1975, 256, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.C.; Martyn, G.D.; Carter, P.J. Fifty years of monoclonals: The past, present and future of antibody therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2025, 25, 745–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullard, A. FDA approves 100th monoclonal antibody product. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, P.J.; Rajpal, A. Designing antibodies as therapeutics. Cell 2022, 185, 2789–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.M.; Wolchok, J.D.; Old, L.J. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Lu, H.; Li, H.; Tang, M.; Tong, A. Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. Mol. Biomed. 2022, 3, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Izadi, S.; Callahan, M.; Deperalta, G.; Wecksler, A.T. Antibody–receptor interactions mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, B.; Kiyotani, K.; Sakata, S.; Nagano, S.; Kumehara, S.; Baba, S.; Besse, B.; Yanagitani, N.; Friboulet, L.; Nishio, M.; et al. Secreted PD-L1 variants mediate resistance to PD-L1 blockade therapy in non–small cell lung cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 982–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varey, A.H.R.; Rennel, E.S.; Qiu, Y.; Bevan, H.S.; Perrin, R.M.; Raffy, S.; Dixon, A.R.; Paraskeva, C.; Zaccheo, O.; Hassan, A.B.; et al. VEGF165b, an antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoform, binds and inhibits bevacizumab treatment in experimental colorectal carcinoma: Balance of pro- and antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoforms has implications for therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 98, 1366–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klümper, N.; Ralser, D.J.; Ellinger, J.; Roghmann, F.; Albrecht, J.; Below, E.; Alajati, A.; Sikic, D.; Breyer, J.; Bolenz, C.; et al. Membranous NECTIN-4 Expression Frequently Decreases during Metastatic Spread of Urothelial Carcinoma and Is Associated with Enfortumab Vedotin Resistance. Clin Cancer Res 2023, 29, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ding, Y.; Zi, M.; Sun, L.; Zhang, W.; Chen, S.; Xu, Y. CD19, from bench to bedside. Immunol. Lett. 2017, 183, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Luo, W.; Li, C.; Mei, H. Targeting CD22 for B-cell hematologic malignancies. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumontet, C.; Reichert, J.M.; Senter, P.D.; Lambert, J.M.; Beck, A. Antibody–drug conjugates come of age in oncology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotillo, E.; Barrett, D.M.; Black, K.L.; Bagashev, A.; Oldridge, D.; Wu, G.; Sussman, R.; LaNauze, C.; Ruella, M.; Gazzara, M.R.; et al. Convergence of Acquired Mutations and Alternative Splicing of CD19 Enables Resistance to CART-19 Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1282–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Gillespie, E.; Naqvi, A.S.; Hayer, K.E.; Ang, Z.; Torres-Diz, M.; Quesnel-Vallières, M.; Hottman, D.A.; Bagashev, A.; Chukinas, J.; et al. Modulation of CD22 Protein Expression in Childhood Leukemia by Pervasive Splicing Aberrations: Implications for CD22-Directed Immunotherapies. Blood Cancer Discov. 2022, 3, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fry, T.J.; Shah, N.N.; Orentas, R.J.; Stetler-Stevenson, M.; Yuan, C.M.; Ramakrishna, S.; Wolters, P.; Martin, S.; Delbrook, C.; Yates, B.; et al. CD22-targeted CAR T cells induce remission in B-ALL that is naive or resistant to CD19-targeted CAR immunotherapy. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braig, F.; Brandt, A.; Goebeler, M.; Tony, H.-P.; Kurze, A.-K.; Nollau, P.; Bumm, T.; Böttcher, S.; Bargou, R.C.; Binder, M. Resistance to anti-CD19/CD3 BiTE in acute lymphoblastic leukemia may be mediated by disrupted CD19 membrane trafficking. Blood 2017, 129, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.; Wu, D.; Cherian, S.; Fang, M.; Hanafi, L.-A.; Finney, O.; Smithers, H.; Jensen, M.C.; Riddell, S.R.; Maloney, D.G.; et al. Acquisition of a CD19-negative myeloid phenotype allows immune escape of MLL-rearranged B-ALL from CD19 CAR-T-cell therapy. Blood 2016, 127, 2406–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-López, M.; Schulz, L.; Enculescu, M.; Paret, C.; Spiekermann, B.; Quesnel-Vallières, M.; Torres-Diz, M.; Unic, S.; Busch, A.; Orekhova, A.; et al. High-throughput mutagenesis identifies mutations and RNA-binding proteins controlling CD19 splicing and CART-19 therapy resistance. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czuczman, M.S.; Olejniczak, S.; Gowda, A.; Kotowski, A.; Binder, A.; Kaur, H.; Knight, J.; Starostik, P.; Deans, J.; Hernandez-Ilizaliturri, F.J. Acquirement of Rituximab Resistance in Lymphoma Cell Lines Is Associated with Both GlobalCD20Gene and Protein Down-Regulation Regulated at the Pretranscriptional and Posttranscriptional Levels. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 1561–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaru, C.; Thiel, J. The need for markers and predictors of Rituximab treatment resistance. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23, 236–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraga, J.; Tomita, A.; Sugimoto, T.; Shimada, K.; Ito, M.; Nakamura, S.; Kiyoi, H.; Kinoshita, T.; Naoe, T. Down-regulation of CD20 expression in B-cell lymphoma cells after treatment with rituximab-containing combination chemotherapies: Its prevalence and clinical significance. Blood 2009, 113, 4885–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeshima, A.M.; Taniguchi, H.; Fujino, T.; Saito, Y.; Ito, Y.; Hatta, S.; Yuda, S.; Makita, S.; Fukuhara, S.; Munakata, W.; et al. Immunohistochemical CD20-negative change in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas after rituximab-containing therapy. Ann. Hematol. 2020, 99, 2141–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, C.K.; Arthur, S.E.; Alcaide, M.; Cheung, M.; Jiang, A.; Coyle, K.M.; Cleary, K.L.S.; Thomas, N.; Hilton, L.K.; Michaud, N.; et al. Genetic and evolutionary patterns of treatment resistance in relapsed B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 2886–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, Z.; Paruzzo, L.; Hayer, K.E.; Schmidt, C.; Diz, M.T.; Xu, F.; Zankharia, U.; Zhang, Y.; Soldan, S.; Zheng, S.; et al. Alternative splicing of its 5′-UTR limits CD20 mRNA translation and enables resistance to CD20-directed immunotherapies. Blood 2023, 142, 1724–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamonet, C.; Bole-Richard, E.; Delherme, A.; Aubin, F.; Toussirot, E.; Garnache-Ottou, F.; Godet, Y.; Ysebaert, L.; Tournilhac, O.; Dartigeas, C.; et al. New CD20 alternative splice variants: Molecular identification and differential expression within hematological B cell malignancies. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 5, 10, Erratum in Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 5, 10.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Faycal, C.; Hatat, A.S.; Gazzeri, S.; Eymin, B. Splice variants of the RTK family: Their role in tumor progression and response to targeted therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, D.M.; Buck, E. Old dog, new tricks: Extracellular domain arginine methylation regulates EGFR function. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 4320–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wei, M.; Piao, H.; He, M. Improving the efficacy of anti-EGFR drugs in GBM: Where we are going? Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Rev. Cancer 2023, 1878, 188996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarden, Y.; Pines, G. The ERBB network: At last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaltriti, M.; Rojo, F.; Ocana, A.; Anido, J.; Guzman, M.; Cortes, J.; Di Cosimo, S.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Ramon y Cajal, S.; Arribas, J.; et al. Expression of p95HER2, a Truncated Form of the HER2 Receptor, and Response to Anti-HER2 Therapies in Breast Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007, 99, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-H.; Zheng, Z.-Q.; Jia, S.; Liu, S.-N.; Xiao, X.-F.; Chen, G.-Y.; Liang, W.-Q.; Lu, X.-F. Trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer: Mechanisms, emerging biomarkers and targeting agents. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1006429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardia, G.D.A.; dos Anjos, C.H.; Rangel-Pozzo, A.; dos Santos, F.F.; Birbrair, A.; Asprino, P.F.; Camargo, A.A.; Galante, P.A. Alternative splicing generates HER2 isoform diversity underlying antibody–drug conjugate resistance in breast cancer. Genome Res. 2025, 35, 1942–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D.; Brumlik, M.J.; Okamgba, S.U.; Zhu, Y.; Duplessis, T.T.; Parvani, J.G.; Lesko, S.M.; Brogi, E.; Jones, F.E. An oncogenic isoform of HER2 associated with locally disseminated breast cancer and trastuzumab resistance. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2009, 8, 2152–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, J.; Ling, C.; Crosby, E.J.; Hartman, Z.C.; Simond, A.M.; A Chodosh, L.; Rennhack, J.P.; Andrechek, E.R.; Ozcelik, J.; Hallett, M.; et al. The ErbB2ΔEx16 splice variant is a major oncogenic driver in breast cancer that promotes a pro-metastatic tumor microenvironment. Oncogene 2016, 35, 6053–6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castiglioni, F.; Tagliabue, E.; Campiglio, M.; Pupa, S.M.; Balsari, A.; Ménard, S. Role of exon-16-deleted HER2 in breast carcinomas. Endocr.-Relat. Cancer 2006, 13, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagnoli, L.; Iezzi, M.; Ghedini, G.C.; Ciravolo, V.; Marzano, G.; Lamolinara, A.; Zappasodi, R.; Gasparini, P.; Campiglio, M.; Amici, A.; et al. Activated d16HER2 Homodimers and SRC Kinase Mediate Optimal Efficacy for Trastuzumab. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 6248–6259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biselli-Chicote, P.M.; Oliveira, A.R.C.P.; Pavarino, E.C.; Goloni-Bertollo, E.M. VEGF gene alternative splicing: Pro- and anti-angiogenic isoforms in cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 138, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanian, F.; Hojati, Z.; Kay, M. New Insights into VEGF-A Alternative Splicing: Key Regulatory Switching in the Pathological Process. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2014, 6, 192–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, N.; Gerber, H.-P.; LeCouter, J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itatani, Y.; Kawada, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Sakai, Y. Resistance to Anti-Angiogenic Therapy in Cancer—Alterations to Anti-VEGF Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolard, J.; Wang, W.-Y.; Bevan, H.S.; Qiu, Y.; Morbidelli, L.; Pritchard-Jones, R.O.; Cui, T.-G.; Sugiono, M.; Waine, E.; Perrin, R.; et al. VEGF165b, an Inhibitory Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Splice Variant. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 7822–7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.O.; Cui, T.-G.; Doughty, J.M.; Winkler, M.; Sugiono, M.; Shields, J.D.; Peat, D.; Gillatt, D.; Harper, S.J. VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 4123–4131. [Google Scholar]

- Cébe-Suarez, S.; Grünewald, F.S.; Jaussi, R.; Li, X.; Claesson-Welsh, L.; Spillmann, D.; Mercer, A.A.; Prota, A.E.; Ballmer-Hofer, K. Orf virus VEGF-E NZ2 promotes paracellular NRP-1/VEGFR-2 coreceptor assembly via the peptide RPPR. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 3078–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, H.; Li, X.; Harper, S.J.; Bates, D.O.; Claesson_Welsh, L. Vascualr endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A165b is a weak in vitro agonist for VEGF receptor-2 due to lack of coreceptor binding and deficient regulation of kinase activity. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 4683–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris-Pagès, M. The role of VEGF165b in pathophysiology. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2012, 6, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, M.; Liu, Y.; Yi, M.; Jiao, D.; Wu, K. Biological Characteristics and Clinical Significance of Soluble PD-1/PD-L1 and Exosomal PD-L1 in Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 827921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, M.; Pratoomthai, B.; Egbuniwe, I.U.; Evans, H.R.; Babaei-Jadidi, R.; Amartey, J.O.; Erdelyi, V.; Yacqub-Usman, K.; Jackson, A.M.; Morris, J.C.; et al. Targeting alternative splicing as a new cancer immunotherapy-phosphorylation of serine arginine-rich splicing factor (SRSF1) by SR protein kinase 1 (SRPK1) regulates alternative splicing of PD1 to generate a soluble antagonistic isoform that prevents T cell exhaustion. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 4001–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yan, L.; Wang, X.; Jia, R.; Guo, J. Surface PD-1 expression in T cells is suppressed by HNRNPK through an exonic splicing silencer on exon. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 73, 1123–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Bai, J.; Jiang, T.; Gao, Y.; Hua, Y. Modulation of PDCD1 exon 3 splicing. RNA Biol. 2019, 16, 1794–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dioken, D.N.; Ozgul, I.; Yilmazbilek, I.; Yakicier, M.C.; Karaca, E.; Erson-Bensan, A.E. An alternatively spliced PD-L1 isoform PD-L1∆3, and PD-L2 expression in breast cancers: Implications for eligibility scoring and immunotherapy response. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 4065–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragu, D.; Necula, L.G.; Bleotu, C.; Diaconu, C.C.; Chivu-Economescu, M. Soluble PD-L1: From Immune Evasion to Cancer Therapy. Life 2025, 15, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlasova, G.; Mraz, M. The regulation and function of CD20: An “enigma” of B-cell biology and targeted therapy. Haematologica 2020, 105, 1494–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, M.S.; Walshe, C.A.; Ivanov, A.O.; Glennie, M.J. The Biology of CD20 and Its Potential as a Target for mAb Therapy. Curr. Dir. Autoimmun. 2005, 8, 140–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, M.J.E.; Stopforth, R.J.; Cragg, M.S. Therapeutic Antibodies: What Have We Learnt from Targeting CD20 and Where Are We Going? Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabkowska, A.; Domka, K.; Firczuk, M. Advancements in cancer immunotherapies targeting CD20: From pioneering monoclonal antibodies to chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1363102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casan, J.M.L.; Wong, J.; Northcott, M.J.; Opat, S. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies: Reviewing a revolution. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2018, 14, 2820–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasunaga, M. Antibody therapeutics and immunoregulation in cancer and autoimmune disease. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 64, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, G.J. Rituximab: Mechanism of Action. Semin. Hematol. 2010, 47, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. Complement system in Anti-CD20 mAb therapy for cancer: A mini-review. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2023, 37, 03946320231181464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wagoner, C.M.; Rivera-Escalera, F.; Jaimes-Delgadillo, N.C.; Chu, C.C.; Zent, C.S.; Elliott, M.R. Antibody-mediated phagocytosis in cancer immunotherapy. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 319, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Hu, W.; Qin, X. The Role of Complement in the Mechanism of Action of Rituximab for B-Cell Lymphoma: Implications for Therapy. Oncologist 2008, 13, 954–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagacean, C.; Zdrenghea, M.; Tempescul, A.; Cristea, V.; Renaudineau, Y. Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibodies in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia: From Uncertainties to Promises. Immunotherapy 2016, 8, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Ni, A.; Bantilan, K.S.; Soumerai, J.D.; Alperovich, A.; Batlevi, C.; Younes, A.; Zelenetz, A.D. The impact of anti-CD20-based therapy on hypogammaglobulinemia in patients with follicular lymphoma. Leuk. Lymphoma 2022, 63, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arteaga, C.L.; Engelman, J.A. ERBB Receptors: From Oncogene Discovery to Basic Science to Mechanism-Based Cancer Therapeutics. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 282–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Hynes, N.; MacDonald, G. ErbB receptors and signaling pathways in cancer. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009, 21, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordella, R.; Bell, D.W.; Haber, D.A.; Settleman, J. Gefitinib-Sensitizing EGFR Mutations in Lung Cancer Activate Anti-Apoptotic Pathways. Science 2004, 305, 1163–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsen, E.-A.; Kahler, S.; Tefay, J.; Joseph, S.R.; Simpson, F. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Expression and Resistance Patterns to Targeted Therapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Review. Cells 2021, 10, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, R.; Gee, J.; Harper, M. EGFR and cancer prognosis. Eur. J. Cancer 2001, 37, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshacharyulu, P.; Ponnusamy, M.P.; Haridas, D.; Jain, M.; Ganti, A.K.; Batra, S.K. Targeting the EGFR signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2012, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.-Q.; Zeng, L.-S.; Wang, L.-F.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Cheng, J.-T.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Z.-W.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, S.-L.; Wang, X.-W.; et al. The Latest Battles Between EGFR Monoclonal Antibodies and Resistant Tumor Cells. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.F.; Noronha, M.M.; de Menezes, J.S.A.; da Conceição, L.D.; Almeida, L.F.C.; Cappellaro, A.P.; Belotto, M.; de Castria, T.B.; Peixoto, R.D.; Megid, T.B.C. Anti-EGFR Therapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Identifying, Tracking, and Overcoming Resistance. Cancers 2025, 17, 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, J. The EGFR as a target for anticancer therapy—Focus on cetuximab. Eur. J. Cancer 2001, 37 (Suppl. 4), 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, T.M.; Iida, M.; Wheeler, D.L. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to the EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011, 11, 777–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Hopper-Borge, E.; E Nasto, R.; Ratushny, V.; Weiner, L.M.; A Golemis, E.; Astsaturov, I. Mechanisms of tumor resistance to EGFR-targeted therapies. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2009, 13, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, L.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, M.; Sun, L.; Peng, P.; Yu, Q.; Yuan, X. Mechanisms of resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 3980–4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukai, J.; Nishio, K.; Itakura, T.; Koizumi, F. Antitumor activity of cetuximab against malignant glioma cells overexpressing EGFR deletion mutant variant III. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99, 2062–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citri, A.; Yarden, Y. EGF–ERBB signalling: Towards the systems level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, G.P.; Shah, R.; Reiman, T.; Wallace, A.; Carter, M.D.; Snow, S.; Fris, J.; Xu, Z. Identification of Driver Mutations and Risk Stratification in Lung Adenocarcinoma via Liquid Biopsy. Cancers 2025, 17, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, N.; Iqbal, N. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in cancers: Overexpression and therapeutic implications. Mol. Biol. Int. 2014, 2014, 852748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javle, M.; Churi, C.; Kang, H.C.; Shroff, R.; Janku, F.; Surapaneni, R.; Zuo, M.; Barrera, C.; Alshamsi, H.; Krishnan, S.; et al. HER2/neu-directed therapy for biliary tract cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 8, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slamon, D.J.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Shak, S.; Fuchs, H.; Paton, V.; Bajamonde, A.; Fleming, T.; Eiermann, W.; Wolter, J.; Pegram, M.; et al. Use of Chemotherapy plus a Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 for Metastatic Breast Cancer That Overexpresses HER. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselga, J.; Cortés, J.; Kim, S.-B.; Im, S.-A.; Hegg, R.; Im, Y.-H.; Roman, L.; Pedrini, J.L.; Pienkowski, T.; Knott, A.; et al. Pertuzumab plus Trastuzumab plus Docetaxel for Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, M.C.; Carey, K.D.; Vajdos, F.F.; Leahy, D.J.; de Vos, A.M.; Sliwkowski, M.X. Insights into ErbB signaling from the structure of the ErbB2-pertuzumab complex. Cancer Cell 2004, 5, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yardley, D.A.; Krop, I.E.; LoRusso, P.M.; Mayer, M.; Barnett, B.; Yoo, B.; Perez, E.A. Trastuzumab Emtansine (T-DM1) in Patients With HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer Previously Treated With Chemotherapy and 2 or More HER2-Targeted Agents. Cancer J. 2015, 21, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modi, S.; Saura, C.; Yamashita, T.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, S.-B.; Tamura, K.; Andre, F.; Iwata, H.; Ito, Y.; Tsurutani, J.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Miles, D.; Gianni, L.; Krop, I.E.; Welslau, M.; Baselga, J.; Pegram, M.; Oh, D.-Y.; Diéras, V.; Guardino, E.; et al. Trastuzumab Emtansine for HER2-Positive Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1783–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, J.; Kim, S.-B.; Chung, W.-P.; Im, S.-A.; Park, Y.H.; Hegg, R.; Kim, M.H.; Tseng, L.-M.; Petry, V.; Chung, C.-F.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan versus Trastuzumab Emtansine for Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitara, K.; Bang, Y.-J.; Iwasa, S.; Sugimoto, N.; Ryu, M.-H.; Sakai, D.; Chung, H.-C.; Kawakami, H.; Yabusaki, H.; Lee, J.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Gastric Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2419–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.A.; Codony-Servat, J.; Albanell, J.; Rojo, F.; Arribas, J.; Baselga, J. Trastuzumab (herceptin), a humanized anti-Her2 receptor monoclonal antibody, inhibits basal and activated Her2 ectodomain cleavage in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4744–4749. [Google Scholar]

- Slamon, D.; Eiermann, W.; Robert, N.; Pienkowski, T.; Martin, M.; Press, M.; Mackey, J.; Glaspy, J.; Chan, A.; Pawlicki, M.; et al. Adjuvant Trastuzumab in HER2-Positive Breast. Cancer 2011, 14, 1273–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Pandiella, A.; Vargas-Castrillón, E.; Diaz-Rodriguez, E.; Iglesias-Hernangomez, T.; Cano, C.M.; Fernández-Cuesta, I.; Winkow, E.; Perelló, M.F. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in breast cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 198, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.M.; Nishino, M.; Lancaster, L.H.; Li, B.T.; Nicholson, A.G.; Bartholmai, B.J.; Naidoo, J.; Schumacher-Wulf, E.; Shitara, K.; Tsurutani, J.; et al. Multidisciplinary clinical guidance on trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd)–related interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis—Focus on proactive monitoring, diagnosis, and management. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 106, 102378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakada, T. Discovery research and translation science of trastuzumab deruxtecan, from non-clinical study to clinical trial. Transl. Regul. Sci. 2021, 3, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautrey, H.; Jackson, C.; Dittrich, A.-L.; Browell, D.; Lennard, T.; Tyson-Capper, A. SRSF3 and hnRNP H1 regulate a splicing hotspot of HER2 in breast cancer cells. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 1139–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurwitz, H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Novotny, W.; Cartwright, T.; Hainsworth, J.; Heim, W.; Berlin, J.; Baron, A.; Griffing, S.; Holmgren, E.; et al. Bevacizumab plus Irinotecan, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2335–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeliet, P.; Jain, R.K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 2011, 473, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Hoareau-Aveilla, C.; Oltean, S.; Harper, S.J.; Bates, D.O. The anti-angiogenic isoforms of VEGF in health and disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2009, 37, 1207–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presta, L.G.; Chen, H.; O’Connor, S.J.; Chisholm, V.; Meng, Y.G.; Krummen, L.; Winkler, M.; Ferrara, N. Humanization of an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody for the therapy of solid tumors and other disorders. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 4593–4599. [Google Scholar]

- Escudier, B.; Pluzanska, A.; Koralewski, P.; Ravaud, A.; Bracarda, S.; Szczylik, C.; Chevreau, C.; Filipek, M.; Melichar, B.; Bajetta, E.; et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: A randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet 2007, 370, 2103–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, S.C.; Pieren, M.; Cariolato, L.; Arn, S.; Hoffmann, U.; Bogucki, A.; Manlius, C.; Wood, J.; Ballmer-Hofer, K. A VEGF-A splice variant defective for heparan sulfate and neuropilin-1 binding shows attenuated signaling through VEGFR-2. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.G.; Woolard, J.; Amin, E.M.; Konopatskaya, O.; Saleem, M.A.; Churchill, A.J.; Ladomery, M.R.; Harper, S.J.; Bates, D.O. Expression of pro- and anti-angiogenic isoforms of VEGF is differentially regulated by splicing and growth factors. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 3487–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, M.; Guiducci, S.; Romano, E.; Ceccarelli, C.; Bellando-Randone, S.; Conforti, M.L.; Ibba-Manneschi, L.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Overexpression of VEGF 165 b, an Inhibitory Splice Variant of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, Leads to Insufficient Angiogenesis in Patients with Systemic Sclerosis. Circ. Res. 2011, 109, e14–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merdzhanova, G.; Gout, S.; Keramidas, M.; Edmond, V.; Coll, J.L.; Brambilla, C.; Brambilla, E.; Gazzeri, S.; Eymin, B. The transcription factor E2F1 and the SR protein SC35 control the ratio of pro-angiogenic verus antiangiogenic isoforms of vascular endothelial growth factor-A to inhibit noevascularization in vivo. Oncogene 2010, 29, 5392–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrou, A.; Brakspear, K.; Hamdollah-Zadeh, M.; Damodaran, G.; Babaei-Jadidi, R.; Oxley, J.; A Gillatt, D.; Ladomery, M.R.; Harper, S.J.; O Bates, D.; et al. Serine–arginine protein kinase 1 (SRPK1) inhibition as a potential novel targeted therapeutic strategy in prostate cancer. Oncogene 2014, 34, 4311–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubol, B.E.; Wu, G.; Keshwani, M.M.; Movassat, M.; Fattet, L.; Hertel, K.J.; Fu, X.-D.; Adams, J.A. Release of SR Proteins from CLK1 by SRPK1: A Symbiotic Kinase System for Phosphorylation Control of Pre-mRNA Splicing. Mol. Cell 2016, 63, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, P.; Pandey, A.; Kakani, P.; Mutnuru, S.A.; Samaiya, A.; Mishra, J.; Shukla, S. Hypoxia-induced loss of SRSF2-dependent DNA methylation promotes CTCF-mediated alternative splicing of VEGFA in breast cancer. iScience 2023, 26, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, M.A.H.; Amin, E.M.; Hoareau-Aveilla, C.; Domingo, E.; Symonds, K.E.; Ye, X.; Heesom, K.J.; Salmon, A.; D’Silva, O.; Betteridge, K.B.; et al. Alternative splicing of TIA-1 in human colon cancer regulates VEGF isoform expression, angiogenesis, tumour growth and bevacizumab resistance. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 9, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Li, Y.; Ding, A.; Zhang, C.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Cheng, S.; Cheng, T.; Wu, S.; et al. A splicing isoform of PD-1 promotes tumor progression as a potential immune checkpoint. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Hu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, Q.; Liu, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, L. Characterization of alternative sPD-1 isoforms reveals that ECD sPD-1 signature predicts an efficient antitumor response. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Fang, J.; Peng, J.; Wang, X.; Xing, P.; Jia, K.; Hu, J.; Wang, D.; Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint blockade in breast cancer: Research insights and sensitization strategies. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohaegbulam, K.C.; Assal, A.; Lazar-Molnar, E.; Yao, Y.; Zang, X. Human cancer immunotherapy with antibodies to the PD-1 and PD-L1 pathway. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Chen, S.; Yang, L.; Li, Y. The role of PD-1 and PD-L1 in T-cell immune suppression in patients with hematological malignancies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ni, Y.; Liang, X.; Lin, Y.; An, B.; He, X.; Zhao, X. Mechanisms of tumor resistance to immune checkpoint blockade and combination strategies to overcome resistance. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 915094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Han, Y.; He, J.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Ning, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Jin, Q.; Yang, L.; Li, S.; et al. Long-read sequencing reveals the landscape of aberrant alternative splicing and novel therapeutic target in colorectal cancer. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Feng, J.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, S. Long-read RNA sequencing dataset of human pancreatic cancer cell lines. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Xia, L.; Xie, D. Long-read RNA sequencing enables full-length chimeric transcript annotation of transposable elements in lung adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Gong, Z.; Wang, G.; Zheng, X.; Zong, W.; Zhao, W.; Xing, P.; Li, R.; et al. ASCancer Atlas: A comprehensive knowledgebase of alternative splicing in human cancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D1196–D1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Fraipont, F.; Gazzeri, S.; Cho, W.C.; Eymin, B. Circular RNAs and RNA Splice Variants as Biomarkers for Prognosis and Therapeutic Response in the Liquid Biopsies of Lung Cancer Patients. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Guo, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Bu, J.; Sun, T.; Wei, J. Liquid biopsy in cancer: Current status, challenges and future prospects. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havens, M.A.; Hastings, M.L. Splice-switching antisense oligonucleotides as therapeutic drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 6549–6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collotta, D.; Bertocchi, I.; Chiapello, E.; Collino, M. Antisense oligonucleotides: A novel Frontier in pharmacological strategy. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1304342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuu, A.; Verreault, M.; Colin, P.; Tran, H.; Idbaih, A. Clinical Applications of Antisense Oligonucleotides in Cancer: A Focus on Glioblastoma. Cells 2024, 13, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagg, B.C.; Uehara, H.; Lambert, N.; Rai, R.; Gupta, I.; Radmall, B.; Bates, T.; Ambati, B.K. Morpholino-Mediated Isoform Modulation of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 (VEGFR2) Reduces Colon Cancer Xenograft Growth. Cancers 2014, 6, 2330–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villiger, L.; Joung, J.; Koblan, L.; Weissman, J.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Gootenberg, J.S. CRISPR technologies for genome, epigenome and transcriptome editing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 464–487, Correction in Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 510.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Ghosh, A.; Chakravarti, R.; Singh, R.; Ravichandiran, V.; Swarnakar, S.; Ghosh, D. Cas13d: A New Molecular Scissor for Transcriptome Engineering. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 866800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konermann, S.; Lotfy, P.; Brideau, N.J.; Oki, J.; Shokhirev, M.N.; Hsu, P.D. Transcriptome Engineering with RNA-Targeting Type VI-D CRISPR Effectors. Cell 2018, 173, 665–676.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiflis, D.N.; Rey, N.A.; Venugopal-Lavanya, H.; Sewell, B.; Mitchell-Dick, A.; Clements, K.N.; Milo, S.; Benkert, A.R.; Rosales, A.; Fergione, S.; et al. Repurposing CRISPR-Cas13 systems for robust mRNA trans-splicing. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Núñez-Álvarez, Y.; Espie-Caullet, T.; Buhagiar, G.; Rubio-Zulaika, A.; Alonso-Marañón, J.; Luna-Pérez, E.; Blazquez, L.; Luco, R.F. A CRISPR-dCas13 RNA-editing tool to study alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 11926–11939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Targets | Gene Names | Splicing Alterations | Pathogenic ISOFORMS | Mechanism | Clinical Relevance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD19 | CD19 | Exon 2 skipping | Δex2 CD19 | Loss of extracellular epitope → CAR-T recognition failure | CD19− relapse after CAR-T therapy | [61,64,65,66] |

| CD22 | CD22 | (1) Exon 2 skipping (2) Exon 5–6 skipping | (1) Δex2 CD22 (2) Δex5–6 CD22 | (1) Loss of protein expression (2) Loss of extracellular domain → ADC/CAR-T escape | - Resistance to inotuzumab ozogamicin - CD22 CAR-T relapse | [62,63] |

| CD20 | MS4A1 | Eson 3–5 skipping | truncated CD20 | Fail to localize to membrane → Reduce CD20 density | - Reduced rituximab binding - primary/relapsed CD20-dim lymphoma | [67,68,69,70,71,72,73] |

| EGFR | ERBB1/ EGFR | (1) Exon 16–17 skipping (2) alternative terminal exon usage | soluble EGFR | Loss of TM domain → soluble decoy that binds ligands and antibodies → reduced membrane EGFR availability | - Variable response to anti-cetuximab, panitumumab - potential mechanism of intrinsic resistance | [74,75,76] |

| HER2 | ERBB2 | Exon 16 skipping | Δ16HER2 | Constitutive dimerization → distorted trastuzumab epitope → reduced ADCC and binding | Resistance to trastuzumab, T-DM1, T-DXd | [77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84] |

| VEGFA | VEGFA | Exon 8a → 8b switching | VEGF165b | Pro- vs anti-angiogenic switch → VEGF165b binds bevacizumab | - Predictor of bevacizumab response - Tumor angiogenesis regulation | [45,46,56,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93] |

| PD-1 | PDCD1 | Exon 3 skipping | soluble PD-1 | Loss of TM domain → soluble decoy binding to PD-L1 → weakens checkpoint blockade | Alter response to anti-PD-1 therapy | [94,95,96,97] |

| PD-L1 | CD274 | (1) Exon 6 or 7 skipping (2) multiple variants | (1) soluble PD-L1 (2) PD-L1v242, PD-L1v229, PD-L1Δ3 | - Secreted isoforms sequester anti-PD-L1 antibodies - Reduced membrane PD-L1 | Anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy resistance | [57,94,95,96,98,99] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, S.; Kang, J.; Kim, J.-H. Alternative Splicing-Mediated Resistance to Antibody-Based Therapies: Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411918

Choi S, Kang J, Kim J-H. Alternative Splicing-Mediated Resistance to Antibody-Based Therapies: Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411918

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Sanga, Jieun Kang, and Jung-Hyun Kim. 2025. "Alternative Splicing-Mediated Resistance to Antibody-Based Therapies: Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411918

APA StyleChoi, S., Kang, J., & Kim, J.-H. (2025). Alternative Splicing-Mediated Resistance to Antibody-Based Therapies: Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411918