Isosorbide Diesters: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Applications in Skin and Neuroinflammatory Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

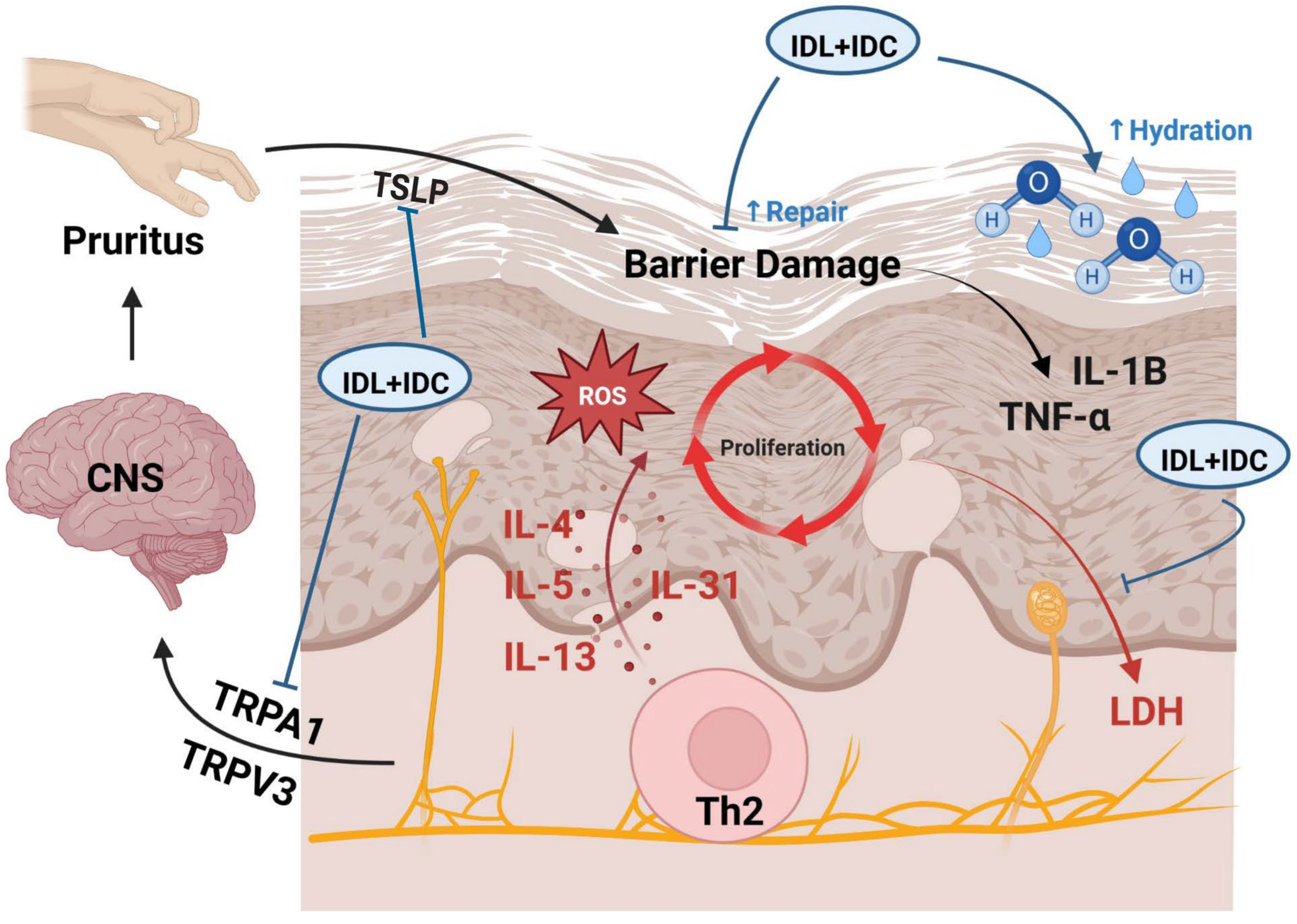

2. Methodology

3. Dermatological Applications

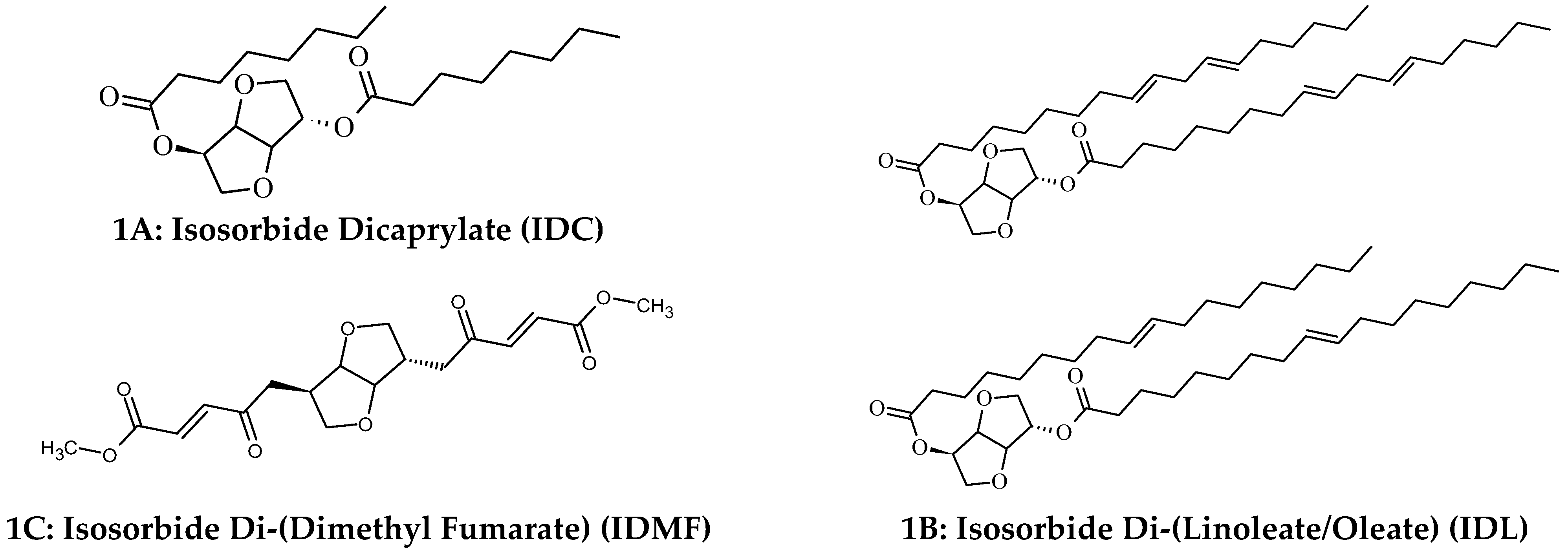

3.1. Cutaneous Metabolism of Di-Fatty Acid Isosorbide Esters

3.2. IDC and IDL Promote Hydration and Restoration of Disrupted Barrier Function

3.2.1. Clinical Studies Confirm That IDC Enhances, Prolongs Skin Hydration and Strengthens the Barrier Function

3.2.2. Mechanistic Insights into IDC’s Ability to Promote Epidermal Skin Hydration

3.2.3. IDL Represses Expression of Inflammatory Genes and Supplements IDC in Stimulation of Pro-Differentiation Genes to Restore Epidermal Barrier Function and Improve Skin Hydration

3.3. IDC + IDL in Management of AD

3.3.1. Therapeutic Outlook of IDC + IDL in Inflammatory Skin Disorders

3.3.2. Clinical Implications and Future Directions for IDC + IDL in Dermatology

3.3.3. Limitations and Future Clinical Studies

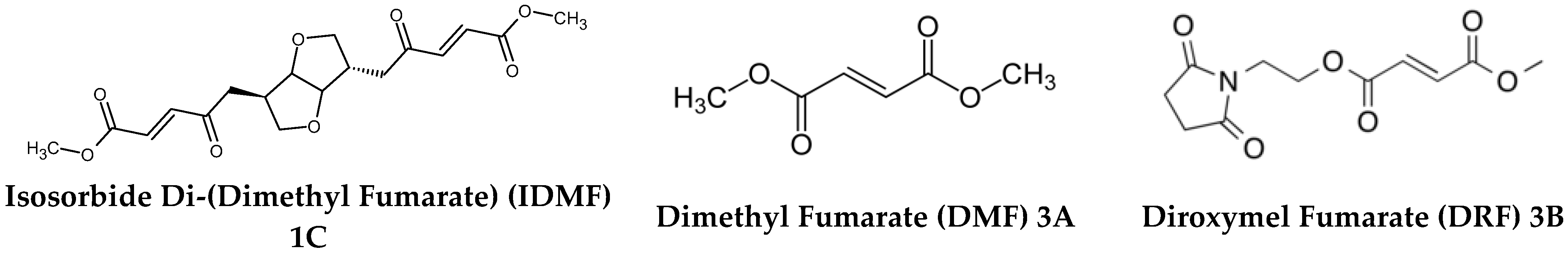

3.4. IDMF in Management of Psoriatic Skin

3.4.1. Therapeutic Outlook of IDMF to Manage Psoriasis

3.4.2. Clinical Implications and Future Directions of IDMF in Psoriasis Treatment

3.4.3. Limitations and Future Clinical Studies

4. Systemic Applications of IDMF

4.1. Rationale for Systemic Evaluation

4.2. Systemic Therapeutic Landscape of Fumarates

4.3. IDMF Mimics DMF-Induced Astrocyte Transcriptomes While Suppressing Reactive Phenotype-Associated Genes

- IDMF preserves NRF2-driven antioxidant defenses as a core mechanistic overlap between IDMF and DMF. Through comprehensive global transcriptome profiling, the study demonstrates that IDMF closely mirrors the gene expression signature elicited by DMF in human astrocytes, particularly in pathways related to cytoprotection, oxidative stress mitigation, and redox homeostasis. Central to this shared response is the robust induction of the NRF2 transcriptional program, a critical determinant of cellular defense against oxidative and electrophilic stress [129]. Within cells, NRF2 serves as a crucial transcription factor and plays an essential role in maintaining the balance of oxidative-reductive reactions and responding to oxidative stress.

- Both IDMF and DMF significantly upregulate canonical NRF2 target genes—including HMOX1 (heme oxygenase 1), NQO1 (NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1), and GCLM (glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit). These genes are instrumental in the detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the maintenance of glutathione levels, and the reinforcement of antioxidant capacity in glial cells. Their consistent activation underscores that IDMF effectively recapitulates the protective molecular footprint that underlies DMF’s established clinical benefits, particularly in the treatment of neuroinflammatory conditions like multiple sclerosis.

- Importantly, this conserved activation of NRF2 signaling suggests that IDMF retains the core mechanistic axis responsible for promoting neuronal resilience and limiting oxidative damage, making it a viable and mechanistically grounded alternative to DMF. By preserving this antioxidant foundation, IDMF maintains a proven therapeutic modality while offering a platform for further refinement and enhancement of fumarate-based treatments. Besides its well-known antioxidant and cytoprotective role, an Nrf2 activator also enhances protein quality control, helping cells detect, tag, and remove damaged proteins through proteasomal and autophagic pathways [130].

- IDMF provides targeted suppression of neurotoxic astrocyte signatures as a distinct anti-inflammatory advantage over DMF. Crucially, while IDMF shares core NRF2-mediated antioxidant functions with DMF, it also diverges sharply in its regulation of astrocyte inflammatory programs, revealing a more refined and targeted therapeutic profile. Transcriptomic analyses uncovered that IDMF selectively downregulates gene networks associated with the A1 reactive astrocyte phenotype, a pro-inflammatory, neurotoxic state that contributes to neuronal degeneration and disease progression in multiple neurological disorders [131].

- Most notably, IDMF exerts strong repressive effects on key A1 astrocyte markers, including C3 (complement component 3), SERPING1 (serpin family G member 1), and GBP2 (guanylate binding protein 2) [128]. These genes play key roles in the amplification of CNS inflammation, initiation of the complement cascade, and promotion of astrocyte-mediated neurotoxicity. Unlike DMF, which shows minimal modulation of these transcripts, IDMF demonstrates a precise anti-inflammatory action, actively attenuating the molecular signature of pathological astrocyte activation.

- This selective repression of reactive astrocyte markers positions IDMF as a fumarate compound with enhanced neuroprotective capacity—not only mitigating oxidative damage but also interrupting key inflammatory feedback loops within the CNS glial environment. The data suggests that IDMF can more effectively blunt the progression of neuroinflammation and limit collateral damage to neurons and oligodendrocytes, offering potential advantages in the treatment of conditions characterized by chronic glial activation, such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and traumatic CNS injury. By modulating both redox balance and inflammatory gene networks with greater precision, IDMF represents a next-generation therapeutic agent capable of delivering dual-action protection: antioxidant reinforcement and active suppression of astrocyte-mediated neuroinflammatory cascades.

4.4. Transcriptomic Profiling of Astrocytes Reveals Distinct Responses to IDMF over Traditional Fumarates

- IDMF demonstrated distinct and potent regulatory effects on a suite of genes associated with the NRF2, NF-κB, and IRF1 signaling pathways comprising key molecular hubs that govern cellular responses to oxidative stress, inflammation, and immune activation. These pathways are critically involved in the pathogenesis of numerous inflammatory and autoimmune skin diseases. Through transcriptomic profiling, the study revealed that IDMF induces a unique expression pattern, markedly different from the other fumarate compounds.

- IDMF’s distinct transcriptomic profile reveals broader and targeted benefits. Gene set enrichment and pathway analyses revealed that IDMF’s transcriptomic signature diverges markedly from that of DMF, reflecting fundamental differences in biological activity at the molecular level. While both compounds modulate pathways linked to oxidative stress and immune regulation, IDMF exhibits a broader and more targeted impact on key gene networks, particularly those associated with anti-inflammatory responses, interferon regulation, and cellular detoxification. Notably, IDMF activates NRF2 target genes more robustly while concurrently exerting greater suppression of pro-inflammatory mediators governed by the NF-κB and IRF1 axes [133].

4.5. Benchmarking IDMF Against Fumarates in Three Disease-Relevant Models

- Oxidative stress model in keratinocytes: IDMF more effectively upregulated antioxidant response elements and suppressed pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8, indicating superior skin-protective properties.

- Inflammation model in the microglial: IDMF significantly inhibited LPS-induced TNF-α and IL-1β production, suggesting enhanced neuroprotective potential relevant for demyelinating CNS disorders.

- PBMC assay: IDMF modulated PBMC cytokine profiles in a manner consistent with an anti-inflammatory phenotype, including suppression of Th1/Th17—associated cytokines, which are crucial mediators in the pathogenesis of both MS and psoriasis.

4.6. Mechanistic Basis of IDMF Action in Neuroinflammation and Multiple Sclerosis

4.7. Therapeutic Outlook for IDMF

- Provide targeted modulation of inflammatory pathways: IDMF exerts distinct and selective effects on key inflammatory transcriptional regulators, including NRF2, NF-κB, and IRF1, suggesting a refined immunomodulatory profile compared to DMF. This positions IDMF as a candidate capable of balancing pro- and anti-inflammatory signaling more precisely than existing therapies.

- Attenuate reactive astrocyte phenotypes: IDMF not only mirrors the DMF-induced transcriptomic signature in astrocytes but also more effectively suppresses genes linked to reactive astrocyte phenotypes—key contributors to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative and demyelinating diseases. This indicates potential for neuroprotection and glial modulation.

- Deliver efficacy across disease models: IDMF exerts broad activity across three preclinical models relevant to both MS and psoriasis, highlighting its multi-tissue efficacy. Importantly, IDMF exhibited superior or comparable activity to DMF in modulating disease-relevant pathways, suggesting translational value in multi-system inflammatory disorders.

4.8. Clinical Implications and Future Directions for IDMF

- Improved safety and tolerability: Its optimized molecular structure and targeted transcriptomic effects may translate to fewer off-target effects and improved tolerability compared to DMF, which is frequently associated with gastrointestinal and flushing-related side effects.

- Dual therapeutic relevance: Demonstrated efficacy in both central nervous system (CNS) and cutaneous models suggests that IDMF may serve as a dual-action therapeutic for comorbid conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and psoriasis, which often co-occur.

- Precision neuroimmunology: Through NRF2 activation and suppression of NF-κB/IRF1 signaling as well as astrocytic reactivity, IDMF represents a step toward precision neuroimmunomodulation, enabling cell type–specific targeting of neuroinflammatory pathways.

4.9. Limitations and Future Clinical Studies

5. Concluding Remarks

- Strengthen epidermal barrier function via activation of genes regulating keratinocyte differentiation, lipid synthesis, and tight junction integrity.

- Upregulate FLG, IVL, and LOR expression at both the transcriptomic (DEG) and protein levels, reinforcing barrier restoration at a molecular scale.

- Enhance hydration through mechanisms beyond passive humectancy, engaging AQP3, AQP9, CD44, and ceramide biosynthesis pathways.

- Suppress inflammation, normalize dysbiosis, reduce corticosteroid reliance, and improve quality of life in AD populations.

- Potent NRF2 activation coupled with NF-κB/IRF1 suppression, attenuating oxidative stress and inflammatory cascades at their molecular origins.

- Superior inhibition of reactive astrocyte phenotypes in neuroinflammatory models, conferring neuroprotection in MS.

- Dual efficacy across cutaneous (psoriasis) and central nervous system (MS) disease models, underscoring its versatility as a precision immunomodulator.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosso, J.D.; Zeichner, J.; Alexis, A.; Cohen, D.; Berson, D. Understanding the epidermal barrier in healthy and compromised skin: Clinically relevant information for the dermatology practitioner. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2016, 9 (Suppl. 1), S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Del Rosso, J.Q.; Levin, J. The clinical relevance of maintaining the functional integrity of the stratum corneum in both healthy and disease-affected skin. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2011, 4, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elias, P.M. Skin barrier function. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008, 8, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Orsmond, A.; Bereza-Malcolm, L.; Lynch, T.; March, L.; Xue, M. Skin Barrier Dysregulation in Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fluhr, J.W.; Moore, D.J.; Lane, M.E.; Lachmann, N.; Rawlings, A. Epidermal barrier function in dry, flaky and sensitive skin: A narrative review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 38, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Man, M.; Li, T.; Elias, P.M.; Mauro, T.M. Aging-associated alterations in epidermal function and their clinical significance. Aging 2020, 12, 5551–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachner, L.A.; Alexis, A.F.; Andriessen, A.; Berson, D.; Gold, M.; Golderberg, D.J.; Hu, S.; Keri, J.; Kircik, L.; Woolery-Lloyd, H. Insights into acne and skin barrier: Optimizing treatment regimens with ceramide-containing skincare. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2023, 22, 2902–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medgyesi, B.; Dajnoki, Z.; Beke, G.; Gaspar, K.; Szabo, I.L.; Janka, E.A.; Poliska, S.; Hendrik, Z.; Mehes, G.; Torocsik, D.; et al. Rosacea is characterized by a profoundly diminished skin barrier. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 140, 1938–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, P.; Nijhawan, S.; Singdia, H.; Mehta, T. Skin Barrier Function Defect-A Marker of Recalcitrant Tinea Infections. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2020, 11, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ye, L.; Mauro, T.M.; Dang, E.; Wang, G.; Hu, L.Z.; Yu, C.; Jeong, S.; Feingold, K.; Elias, P.M.; Lv, C.Z.; et al. Topical applications of an emollient reduce circulating pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in chronically aged humans: A pilot clinical study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 33, 2197–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, B.; Lv, C.; Ye, L.; Wang, Z.; Kim, Y.; Luo, W.; Elias, P.M.; Man, M.Q. Stratum corneum hydration inversely correlates with certain serum cytokine levels in the elderly, possibly contributing to inflammaging. Immun. Ageing 2023, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, R.K.; An, Y.; Zukley, L.; Ferrucci, L.; Mauro, T.; Yaffe, K.; Resnick, S.M.; Abuabara, K. Skin barrier function and cognition among older adults. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 143, 1085–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Seok, J.K.; Kang, H.C.; Cho, Y.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.Y. Skin barrier abnormalities and immune dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Amagai, M. Dissecting the formation, structure and barrier function of the stratum corneum. Int. Immunol. 2015, 27, 269–280, Correction in Int. Immunol. 2017, 29, 243–244. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxx024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cork, M.J.; Danby, S.G.; Vasilopoulos, Y.; Hadgraft, J.; Lane, M.E.; Moustafa, M.; Guy, R.H.; MacGown, A.L.; Tazi-Ahnini, R.; Ward, S.J. Epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 1892–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreci, R.S.; Lechler, T. Epidermal structure and differentiation. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R144–R149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamatas, G.N. Protein degradation in the stratum corneum. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2024, 46, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, P.M. Stratum corneum defensive functions: An integrated view. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrado, C.; Mercado-Saenz, S.; Perez-Davo, A.; Gilaberte, Y.; Gonzalez, S.; Juarranz, A. Environmental Stressors on Skin Aging. Mechanistic Insights. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beck, L.A.; Cork, M.J.; Amagai, M.; De Benedetto, A.; Kabashima, K.; Hamilton, J.D.; Rossi, A.B. Type 2 inflammation contributes to skin barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. JID Innov. 2022, 2, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, P.M.; Steinhoff, M. “Outside-to-inside” (and now back to outside) pathogenic mechanisms in atopic dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, J.M. Therapeutic implications of a barrier-based pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Ann. Dermatol. 2010, 22, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, S.M.; Bulfone-Paus, S.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Watson, R.E.B. Inflammaging and the skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.S.; Bieber, T.B.; Williams, H.C. Are the concepts of induction of remission and treatment of subclinical inflammation in atopic dermatitis clinically useful? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 133, 1615–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Hu, A.; Bollag, W.B. The Skin and Inflamm-Aging. Biology 2023, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Elias, P.M. Optimizing emollient therapy for skin barrier repair in atopic dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022, 128, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bogaard, E.H.; Elias, P.M.; Goleva, E.; Berdyshev, E.; Smits, J.P.H.; Danby, S.G.; Cork, M.J.; Leung, D.Y.M. Targeting skin barrier function in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2023, 11, 1335–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danby, S.G.; Chalmers, J.; Brown, K.; Williams, H.C.; Cork, M.J. A functional mechanistic study of the effect of emollients on the structure and function of the skin barrier. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 1011–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmuth, M.; Eckmann, S.; Moosbrugger-Martinez, V.; Ortner-Tobider, D.; Blunder, S.; Trafoier, T.; Guber, R.; Elias, P.M. Skin barrier in atopic dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 144, 989–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagami, H.; Kobayashi, H.; O’goshi, K.; Kikuchi, K. Atopic xerosis: Employment of noninvasive biophysical instrumentation for the functional analyses of the mildly abnormal stratum corneum and for the efficacy assessment of skin care products. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2006, 5, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicol, N.H.; Rippke, F.; Weber, T.M.; Hebert, A.A. Daily moisturization for atopic dermatitis: Importance, recommendations and moisturizer choices. J. Nurse Pract. 2021, 17, 920–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, A.K. Skin aging & modern age anti-aging strategies. Int. J. Clin. Dermatol. Res. 2019, 7, 209–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buraczewska, I.; Berne, B.; Lindberg, M.; Torma, H.; Loden, M. Changes in skin barrier function following long-term treatment with moisturizers, a randomized clinical trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2007, 156, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowther, J.M.; Sieg, A.; Blenkiron, P.; Marcott, C.; Matts, P.J.; Kaczvinsky, J.R.; Rawlings, A.V. Measuring the effects of topical moisturizers on changes in stratum corneum thickness, water gradients and hydration in vivo. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 159, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, D.S.; Ali, Z.K.; Hameed, S.A.; Aldosky, H.Y.Y. Evaluation of the effect of several moisturizing creams using the low frequency electrical susceptance approach. J. Electr. Bioimpedance 2024, 15, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhengxiao, L.; Hu, L.; Elias, P.M.; Man, M. Skin care products can aggravate epidermal function: Studies in a murine model suggest a pathogenic role in sensitive skin. Contact Dermat. 2017, 78, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerstrom, U.; Reitamo, S.; Langeland, T.; Berg, M.; Rustad, L.; Korhonen, L.; Loden, M.; Wiren, K.; Grande, M.; Skare, P.; et al. Comparison of moisturizing creams for the prevention of atopic dermatitis relapse: A randomized double-blind controlled multicentre clinical trial. Acta Derm.-Venereol. 2015, 95, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elias, P.M.; Sugarman, J. Clinical perspective: Moisturizers vs. barrier repair in the management of atopic dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018, 121, 653–656.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danby, S.G.; Andrew, P.V.; Taylor, R.N.; Kay, L.J.; Chittock, J.; Pinnock, A.; Ulhaq, I.; Fasth, A.; Carlander, K.; Holm, T.; et al. Different types of emollient cream exhibit diverse physiological effects on the skin barrier in adults with atopic dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danby, S.G.; Al-Enezi, T.; Sultan, A.; Chittock, J.; Kennedy, K.; Cork, M.J. The effect of aqueous cream BP on the skin barrier in volunteers with a previous history of atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 165, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.H.; Kang, H. Importance of stratum corneum acidification to restore skin barrier function in eczematous diseases. Ann. Dermatol. 2024, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, P.V.; Pinnock, A.; Poyner, A.; Brown, K.; Chittock, J.; Kay, L.J.; Cork, M.J. Maintenance of an acidic skin surface with a novel zinc lactobionate emollient preparation improves skin barrier function in patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatol. Ther. 2024, 14, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purnamawati, S.; Indrastuti, N.; Danarti, R.; Saefudin, T. The role of moisturizers in addressing various kinds of dermatitis: A review. Clin. Med. Res. 2017, 15, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, W.; Fan, L.; Tian, Y.; Congfen, H. Study of the protective effects of cosmetic ingredients on the skin barrier, based on the expression of barrier-related genes and cytokines. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buraczewska, I.; Berne, B.; Lindberg, M.; Loden, M.; Torma, H. Moisturizers change the mRNA expression of enzymes synthesizing skin barrier lipids. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2009, 301, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Hu, J.; Liu, J.; Lu, S.W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Stereoselective characteristics and mechanism of epidermal carboxylesterase metabolism observed in HaCaT keratinocytes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmer, J.F.; Lally, M.N.; Gardiner, P.; Dillon, G.; Gaynor, J.M.; Reidy, S. Novel isosorbide-based substates for human butyrylcholinesterase. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2005, 157–158, 317–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonte, F. Skin moisturization mechanisms: New data. In Annales Pharmaceutiques Francaises; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 69, pp. 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, R.K.; Bojanowski, K. Improvement of hydration and epidermal barrier function in human skin by a novel compound isosorbide dicaprylate. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2017, 39, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.H.; Man, M.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Brown, B.E.; Feingold, K.R.; Elias, P.M. Is endogenous glycerol a determinant of stratum corneum hydration in humans? J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncheva, M. The physical chemistry of the stratum corneum lipids. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2014, 36, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwstra, J.; Nadaban, A.; Bras, W.; McCabe, C.; Bunge, A.; Gooris, G.S. The skin barrier: An extraordinary interface with an exceptional lipid organization. Prog. Lipid Res. 2023, 92, 101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J. Understanding the role of natural moisturizing factor in skin hydration. Pract. Dermatol. 2012, 9, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mojumdar, E.H.; Pham, Q.D.; Topgaard, D.; Sparr, E. Skin hydration: Interplay between molecular dynamics, structure and water uptake in the stratum corneum. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boury-Jamot, M.; Sougrat, R.; Tailhardat, M.; Le Varlet, B.; Bonte, F.; Dumas, M.; Verbavatz, J.M. Expression and function of aquaporins in human skin: Is aquaporin-3 just a glycerol transporter? Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)–Biomembr. 2006, 1758, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, M.; Ma, T.; Verkman, A.S. Selectively reduced glycerol in skin of aquaporin-3 deficient mice amy account for impaired skin hydration, elasticity and barrier recovery. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 46616–46621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, M.; Verkman, A.S. Glycerol replacement corrects defective skin hydration, elasticity and barrier function in aquaporin-3 deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 7360–7365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, A.; Siefken, W.; Kueper, T.; Breitenback, U.; Gatermann, C.; Sperling, G.; Biernoth, T.; Scherner, C.; Stab, F.; Wenck, H.; et al. Effects of glyceryl glucoside on AQP3 expression, barrier function and hydration of human skin. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2012, 25, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungersted, J.M.; Bomholt, J.; Bajraktari, N.; Hansen, J.S.; Klærke, D.A.; Pedersen, P.A.; Hedfalk, K.; Nielsen, K.H.; Agner, T.; Hélix-Nielsen, C. In vivo studies of aquaporins 3 and 10 in human stratum corneum. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2013, 305, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underhill, C. CD44: The hyaluranon receptor. J. Cell Sci. 1992, 103, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Roth, M.; Karakiulkis, G. Hyaluronic acid: A key molecule in skin aging. Dermatoendocrinol 2012, 4, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammi, R.; Ripellino, J.A.; Margolis, R.U.; Tammi, M. Localization of epidermal hyaluronic acid using the hyaluronate binding region of cartilage proteoglycan as a specific probe. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1988, 90, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourguignon, L.Y.W.; Ramez, M.; Gilad, E.; Singleton, P.A.; Man, M.; Crumrine, D.A.; Elias, P.M.; Feingold, K.R. Hyaluranon-CD44 interaction stimulates keratinocyte differentiation, lamellar body formation/secretion, and permeability barrier homeostasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2006, 126, 1356–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, N.; Haftek, M.; Niessen, C.M.; Behne, M.J.; Furuse, M.; Moll, I.; Brandner, M. CD44 regulates tight-junction assembly and barrier function. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, G.; Rodriguez, I.; Jorcano, J.L.; Vassalli, P.; Stamenkovic, I. Selective suppression of CD44 in keratinocytes of mice bearing an antisense CD44 transgene driven by a tissue-specific promoter disrupts hyaluronate metabolism in the skin and impairs keratinocyte proliferation. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 996–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, H.K.; Maiers, J.L.; DeMali, K.A. Interplay between tight junctions and adherens junctions. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 358, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunggal, J.A.; Helfrich, I.; Schmitz, A.; Schwarz, H.; Günzel, D.; Fromm, M.; Kemler, R.; Krieg, T.; Niessen, C.M. E-cadherin is essential for in vivo epidermal barrier function by regulating tight junctions. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 1146–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, S.; O’Boyle, N.M. Skin lipids in health and disease: A review. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2021, 236, 105055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdyshev, E. Skin lipid barrier: Structure, function and metabolism. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2024, 16, 445–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennemann, R.; Rabionet, M.; Gorgas, K.; Epstein, S.; Dalpke, A.; Rothermel, U.; Bayerle, A.; Van der Hoeven, F.; Imgrund, S.; Kirsch, J.; et al. Loss of ceramide synthase 3 causes lethal skin barrier disruption. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 586–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, B.; Tilli, C.M.; Hardman, M.J.; Avilion, A.A.; MacLeod, M.C.; Ashcroft, G.S.; Byrne, C.J. Late cornified envelope family in differentiating epithelia—response to calcium and ultraviolet irradiation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 124, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohl, D.; de Viragh, P.A.; Amiguet-Barras, F.; Gibbs, S.; Beckendorf, C.; Huber, M. The small proline-rich proteins constitute a multigene family of differentially regulated cornified cell envelope precursor proteins. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1995, 104, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candi, E.; Schmidt, R.; Melino, G. The cornified envelope: A model of cell death in the skin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, P.M.; Candi, E.; Tarcsa, E.; Marekov, L.N.; Sette, M.; Paci, M.; Ciani, B.; Guerrieri, P.; Melino, G. Transglutaminase crosslinking and structural studies of the human small proline rich 3 protein. Cell Death Differ. 1999, 6, 916–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verjeij, W.; Backendorf, C. Skin cornification proteins provide global link between ROS detoxification and cell migration during wound healing. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hu, Z.; Lone, A.G.; Artami, M.; Edwards, M.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Stein, M.; Harris-Tryon, T.A. Small proline-rich proteins (SPRRs) are epidermally produced antimicrobial proteins that defend the cutaneous barrier by direct bacterial membrane disruption. eLife 2022, 11, e76729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabini, A.; Zimmer, Y.; Medova, M. Beyond keratinocyte differentiation: Emerging new biology of the small proline-rich proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 2023, 33, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanowski, K.; Swindell, W.R.; Cantor, S.; Chaudhuri, R.K. Isosorbide di-(linoleate/oleate) stimulates prodifferentiation gene expression to restore the epidermal barrier and improve skin hydration. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1416–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanovic, N.; Irvine, A.D. Filaggrin and beyond: New insights into the skin barrier in atopic dermatitis and allergic diseases, from genetics to therapeutic perspectives. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024, 132, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishitsuka, Y.; Roop, D.R. Loricrin: Past, Present, and Future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swindell, W.R.; Johnston, A.; Xing, X.; Voorhees, J.J.; Elder, J.T.; Gudjonsson, J.E. Modulation of epidermal transcription circuits in psoriasis: New links between inflammation and hypoproliferation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, A.; Voskamp, P.; Cleton-Jansen, A.; South, A.; Nizetie, D.; Backendorf, C. Structural organization and regulation of the small proline-rich family of cornified envelope precursors suggest a role in adaptive barrier function. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 19231–19237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.E.; Choi, H.; Shin, D.W.; Na, H.W.; Park, N.Y.; Kim, J.B.; Jo, D.S.; Cho, M.J.; Lyu, J.H.; Chang, J.H.; et al. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) inhibits ciliogenesis by increasing SPRR3 expression via c-Jun activation in RPE cells and skin keratinocytes. Sci Rep. 2019, 9, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, M.C.M.; Mao, G.; Saad, P.; Flach, C.R.; Mendelsohn, R.; Walters, R.M. Molecular interactions of plant oil components with stratum corneum lipids correlates with clinical measures of skin barrier function. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; He, H. The role of linoleic acid in skin and hair health: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabionet, M.; Gorgas, K.; Sandoff, R. Ceramide synthesis in the epidermis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2014, 1841, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, A.A.; Rippke, F.; Weber, T.M.; Nicol, H.N. Efficacy of nonprescription moisturizers for atopic dermatitis: An updated review of clinical evidence. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 21, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leman, G.; Pavel, P.; Hermann, M.; Crumrine, D.; Elias, P.M.; Minzaghi, D.; Goudounèche, D.; Roshardt Prieto, N.M.; Cavinato, M.; Wanner, A.; et al. Mitochondrial activity is upregulated in nonlesional atopic dermatitis and amenable to therapeutic intervention. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 2623–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindell, W.R.; Bojanowski, K.; Chaudhuri, R.K. Isosorbide fatty acid diesters have synergistic anti-inflammatory effects in cytokine-induced tissue culture models of atopic dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadora, D.; Burney, W.; Chaudhuri, R.K.; Galati, A.; Min, M.; Fong, S.; Lo, K.; Chambers, C.; Sivamani, R.K. Prospective randomized double-blind vehicle-controlled study of topical coconut and sunflower seed oil-derived isosorbide diesters on atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis 2024, 35, S62–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Dulai, A.S.; O’Neill, A.; Min, M.; Lee, J.; Dion, C.; Afzal, N.; Chaudhuri, R.K.; Sivamani, R.K. Impact of Isosorbide Diesters from Coconut and Sunflower Fatty Acids on Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis and the Skin Microbiome: A Randomized Double-Blind Vehicle-Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2025. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, J.; Lax, S.J.; Lowe, A.; Santer, M.; Lawton, S.; Langan, S.M.; Roberts, A.; Stuart, B.; Williams, H.C.; Thomas, K.S. The long-term safety of topical corticosteroids in atopic dermatitis: A systematic review. Skin Health Dis. 2023, 3, e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsuji, T.; Gallo, R.L. The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 122, 263–269, Erratum in Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 123, 529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2019.08.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.L.; Villarreal, M.; Jepson, B.; Rafaels, N.; David, G.; Hanifin, J.; Taylor, P.; Boguniewicz, M.; Yoshida, T.; De Benedetto, A.; et al. Patients with atopic dermatitis subjects colonized with Staphhylococcus aureus have a distinct phenotype and endotype. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 2224–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demessant-Flavigny, A.L.; Connetable, S.; Kerob, D.; Moreau, M.; Aguilar, L.; Wollenberg, A. Skin microbiome dysbiosis and the role of Staphhylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis in adultsand children: A narrative review. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2023, 37 (Suppl. 5), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanowski, K.; Ibeji, C.U.; Singh, P.; Swindell, W.R.; Chaudhuri, R.K. A sensitization-free dimethyl fumarate prodrug, isosorbide di-(methyl fumarate), provides a topical treatment candidate for psoriasis. JID Innov. 2021, 1, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Held, K.D.; Epp, E.R.; Awad, S.; Biaglow, J.E. Postirradiation sensitization of mammalian cells by the thiol-depleting agent dimethyl fumarate. Radiat. Res. 1991, 127, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Ruiz, A.; Kornacker, K.; Brash, D.E. Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer hyperhotspots as sensitive indicators of keratinocyte UV exposure. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 98, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, P.; Brown, A.J.; Esaki, S.; Lockwood, S.; Poon, G.M.K.; Smerdon, M.J.; Roberts, S.A.; Wyrick, J.J. ETS transcription factors induce a unique UV damage signature that drives recurrent mutagenesis in melanoma. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, K.A.; Morledge-Hampton, B.; Stevison, S.; Mao, P.; Roberts, S.A.; Wyrick, J.J. Genome-wide maps of rare and atypical UV photoproducts reveal distinct patterns of damage formation and mutagenesis in yeast chromatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2216907120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Ratnakumar, K.; Hung, K.F.; Rokunohe, D.; Kawasumi, M. Deciphering UV-induced DNA damage responses to prevent and treat skin cancer. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 478–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitsiou, E.; Pulido, T.; Campisi, J.; Alimirah, F.; Demaria, M. Cellular senescence and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype as drivers of skin photoaging. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebo, K.B.; Bonnekoh, B.; Geisel, J.; Mahrle, G. Antiproliferative and cytotoxic profiles of anti-psoriatic fumaric acid derivatives in keratinocyte cultures. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1994, 270, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thio, H.B.; Zomerdijk, T.P.; Oudshoorn, C.; Kempenaar, J.; Nibbering, P.H.; van der Schroeff, J.G.; Ponec, M. Fumaric acid derivatives evoke a transient increase in intracellular free calcium concentration and inhibit the proliferation of human keratinocytes. Br. J. Dermatol. 1994, 131, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helwa, I.; Patel, R.; Karempelis, P.; Kaddour-Djebbar, I.; Choudhary, V.; Bollag, W.B. The antipsoriatic agent monomethylfumarate has antiproliferative, prodifferentiative, and anti-inflammatory effects on keratinocytes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2015, 352, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoof, T.J.; Flier, J.; Sampat, S.; Nieboer, C.; Tensen, C.P.; Boorsma, D.M. The antipsoriatic drug dimethylfumarate strongly suppresses chemokine production in human keratinocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Br. J. Dermatol. 2001, 144, 1114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruck, J.; Dringen, R.; Amasuno, A.; Pau-Charles, I.; Ghoreschi, K. A review of the mechanisms of action of dimethylfumarate in the treatment of psoriasis. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 27, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdes, S.; Shakery, K.; Mrowietz, U. Dimethylfumarate inhibits nuclear binding of nuclear factor kappaB but not of nuclear factor of activated T cells and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta in activated human T cells. Br. J. Dermatol. 2007, 156, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandermeeren, M.; Janssens, S.; Wouters, H.; Borghmans, I.; Borgers, M.; Beyaert, R.; Geysen, J. Dimethylfumarate is an inhibitor of cytokine-induced nuclear translocation of NF-kappa B1, but not RelA in normal human dermal fibroblast cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2001, 116, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesser, B.; Rasmussen, M.K.; Raaby, L.; Rosada, C.; Johansen, C.; Kjellerup, R.B.; Kragballe, K.; Iversen, L. Dimethylfumarate inhibits MIF-induced proliferation of keratinocytes by inhibiting MSK1 and RSK1 activation and by inducing nuclear p-c-Jun (S63) and p-p53 (S15) expression. Inflamm. Res. 2011, 60, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillard, G.O.; Collette, B.; Anderson, J.; Chao, J.; Scannevin, R.H.; Huss, D.J.; Fontenot, J.D. DMF, but not other fumarates, inhibits NF-kB activity in vitro in an Nrf2-independent manner. J. Neuroimmunol. 2015, 283, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, P.; Merfort, I.; Tamm, M.; Roth, M. Inhibition of NF-kB and AP-1 by dimethylfumarate correlates with down-regulated IL-6 secretion and proliferation in human lung fibroblasts. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2010, 140, w13132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleńkowska, J.; Gabig-Cimińska, M.; Mozolewski, P. Oxidative stress as an important contributor to the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, A.J.; Ashby, L.V.; Winterbourn, C.C.; Dickerhof, N. Superoxide: The enigmatic chemical chameleon in neutrophil biology. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 314, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manai, F.; Amadio, M. Dimethyl fumarate triggers the antioxidant defense system in human retinal endothelial cells through Nrf2 activation. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helwa, I.; Choudhary, V.; Chen, X.; Kaddour-Djebbar, I.; Bollag, W.B. Anti-psoriatic drug monomethylfumarate increases nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 levels and induces aquaporin-3 mRNA and protein expression. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 362, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.J.; Bae, J.H.; Kang, S.G.; Cho, S.W.; Chun, D.I.; Nam, S.M.; Lee, S.H.; Cho, M.K. Pro-oxidant status and Nrf2 levels in psoriasis vulgaris skin tissues and dimethyl fumarate treated HaCaT cells. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2017, 40, 1105–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akino, N.; Wada-Hiraike, O.; Isono, W.; Terao, H.; Honjo, H.; Miyamoto, Y.; Tanikawa, M.; Sone, K.; Hirano, M.; Harada, M.; et al. Activation of Nrf2/Keap1 pathway by oral DMF Dimethylfumarate administration alleviates oxidative stress and age-associated infertility might be delayed in the mouse ovary. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2019, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.C.; Cheng, W.J.; Korinek, M.; Lin, C.Y.; Hwang, T.L. Neutrophils in psoriasis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, M.; Boisgard, A.S.; Danoy, A.; Kholti, N.E.; Salvi, J.; Boulieu, R.; Fromy, B.; Verrier, B.; Lamrayah, M. Advanced characterization of imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mouse model. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestre, J.F.; Mercader, P.; Giménez-Arnau, A.M. Contact dermatitis due to dimethyl fumarate. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2010, 101, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourakis, S.; Timpani, C.A.; de Haan, J.B.; Gueven, N.; Fischer, D.; Rybalka, E. Dimethyl Fumarate and Its Esters: A Drug with Broad Clinical Utility? Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brescani, G.; Manai, F.; Davinelli, S.; Tucci, P.; Saso, L.; Amadio, M. Novel potential pharmacological applications of dimethyl furmarate- an overview and update. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1264842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majkutewicz, I. Dimethyl fumarate: A review of preclinical efficacy in models of neurodegenerative diseases. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 926, 175025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naismith, R.T.; Wundes, A.; Ziemssen, T.; Jasinska, E.; Freedman, M.S.; Lembo, A.J.; Selmaj, K.; Bidollari, I.; Chen, H.; Hanna, J.; et al. EVOLVE-MS-2 Study Group. Diroximel Fumarate Demonstrates an Improved Gastrointestinal Tolerability Profile Compared with Dimethyl Fumarate in Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Results from the Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase III EVOLVE-MS-2 Study. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wray, S.; Then-Bergh, F.; Arnold, D.L.; Drulovic, J.; Jasinska, E.; Bowen, J.D.; Negroski, D.; Naismith, R.T.; Hunter, S.F.; Gudesblatt, M.; et al. Phase 3 EVOLVE-MS-1 after switching from glatiramer acetate or interferon or continuing on diroximel fumarate [Poster presentation]. In Proceedings of the MS Trust Conference, Jurys Inn Hinckley Island Hotel, UK, 26 March 2023; Available online: https://mstrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-06/conference-poster-2023-evolve-ms-flushing-study.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Baskaran, A.B.; Grebenciucova, E.; Shoemaker, T.; Graham, E.L. Current Updates on the Diagnosis and Management of Multiple Sclerosis for the General Neurologist. J. Clin. Neurol. 2023, 19, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swindell, W.R.; Bojanowski, K.; Chaudhuri, R.K. A novel fumarate, isosorbide di (methyl fumarate) (IDMF), replicates astrocyte transcriptome responses to dimethyl fumarate (DMF) but specifically down regulates genes linked to a reactive phenotype. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 532, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, J.; Wu, C.; Tang, S.; Bian, W.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Wu, Y.; Li, S.; et al. Targeting epigenetic and post-translational modifications of NRF2: Key regulatory factors in disease treatment. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Lai, Y.; Janicki, J.S.; Wang, X. Nuclear factor erythroid-2 related factor 2 (Nrf2)-mediated protein quality control in cardiomyocytes. Front. Biosci. 2016, 21, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, J.L.; Xu, L.; Foo, L.C.; Nouri, N.; Zhou, L.; Giffard, R.G.; Barres, B.A. Genomic analysis of reactive astrogliosis. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 6391–6410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunki, M.; Amormino, C.; Tedeschi, V.; Fiorillo, M.T.; Tuosto, L. Astrocytes and inflammatory T helper cells: A dangerous liaison in multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 82441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindell, W.R.; Bojanowski, K.; Chaudhuri, R.K. Transcriptomic Analysis of Fumarate Compounds Identifies Unique Effects of Isosorbide Di (Methyl Fumarate) on NRF2, NF κB and IRF1 Pathway Genes. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, S.; Paulet, V.; Hardonnière, K.; Kerdine-Römer, S. The role of NRF2 transcription factor in inflammatory skin diseases. BioFactors 2025, 51, e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Gong, G.; Quijas, G.; Lee, S.M.Y.; Chaudhuri, R.K.; Bojanowski, K. Comparative activity of dimethyl fumarate derivative IDMF in three models relevant to multiple sclerosis and psoriasis. FEBS Open Bio 2025, 15, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Adult Study (4-Weeks) | Pediatric Study (8-Weeks) (2–17 years old) |

|---|---|---|

| EASI Scores Achieved | EASI-75: 57% vs. 25% (p = 0.04) at week 4 | EASI-50: 81% vs. 56% (p = 0.10) * at week 8 |

| Itch Reduction (IVAS) | ≥4-point reduction in 66% vs. 44% (p = 0.013) at week 4 | ≥4-point reduction in 43% vs. 13% (p = 0.045) at week 8 |

| Topical Corticosteroid (TCS) Use | Reduced by 25% vs. 292% increase (p = 0.039) at week 1 Reduced by 46% vs. 220% increase (p = 0.08) * at week 2 | 3.4 g vs. 13.3 g TCS (p = 0.12) * at week 8 47% vs. 20% (p = 0.097) * never used TCS at week 8 |

| Abundance of S. aureus | Reduction vs. no change (p = 0.044) at week 4 | Reduction vs. elevation (p= 0.0000) at week 8 |

| Improvement in Sleep or DLQI Ratings | 53% vs. 26% (p= 0.02) improvement in group with moderate-to-severe sleeplessness | Significant (p = 0.035) vs. insignificant (p = 0.35) reduction in DLQI at week 8 |

| Safety | No adverse effects | No adverse effects |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chaudhuri, R.K.; Meyer, T.A. Isosorbide Diesters: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Applications in Skin and Neuroinflammatory Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411855

Chaudhuri RK, Meyer TA. Isosorbide Diesters: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Applications in Skin and Neuroinflammatory Disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411855

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaudhuri, Ratan K., and Thomas A. Meyer. 2025. "Isosorbide Diesters: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Applications in Skin and Neuroinflammatory Disorders" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411855

APA StyleChaudhuri, R. K., & Meyer, T. A. (2025). Isosorbide Diesters: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Applications in Skin and Neuroinflammatory Disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11855. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411855