Linking Cell Architecture to Mitochondrial Signaling in Neurodegeneration: The Role of Intermediate Filaments

Abstract

1. Introduction

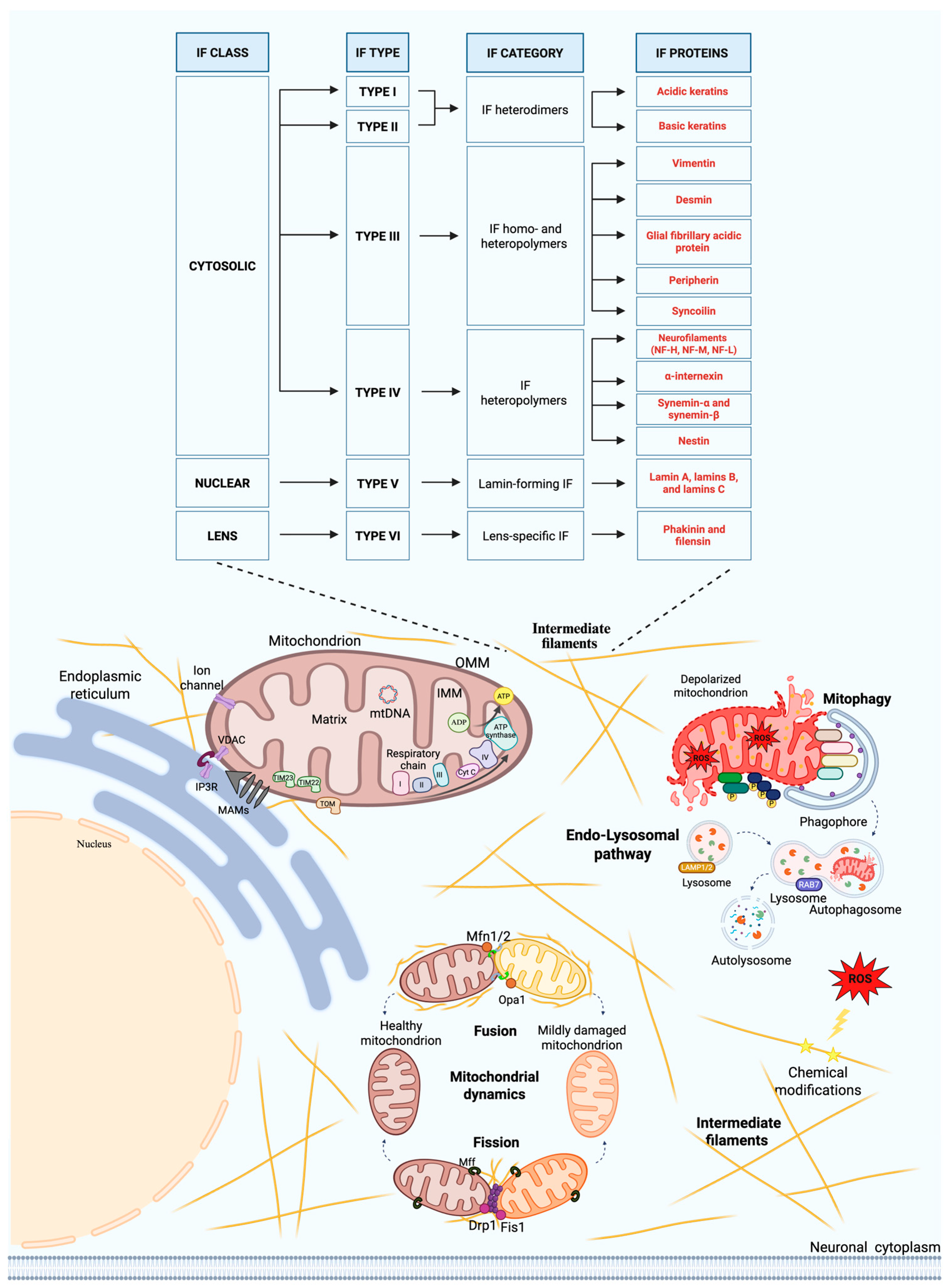

2. Intermediate Filaments: Ultrastructure and Functional Roles in Neurons

3. Intermediate Filaments and Mitochondria Interactions

3.1. Vimentin and Desmin

3.2. Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein

3.3. Neurofilaments

3.4. Peripherin

4. Physiological Roles of Intermediate Filaments and Mitochondrial Crosstalk in Neurons

4.1. Intermediate Filaments in Mitochondria–Endoplasmic Reticulum Interactions

4.2. Intermediate Filaments and Mitochondrial Dynamics

4.3. Intermediate Filaments and Mitochondrial Redox Regulation

4.4. Intermediate Filaments and the Endo-Lysosomal System

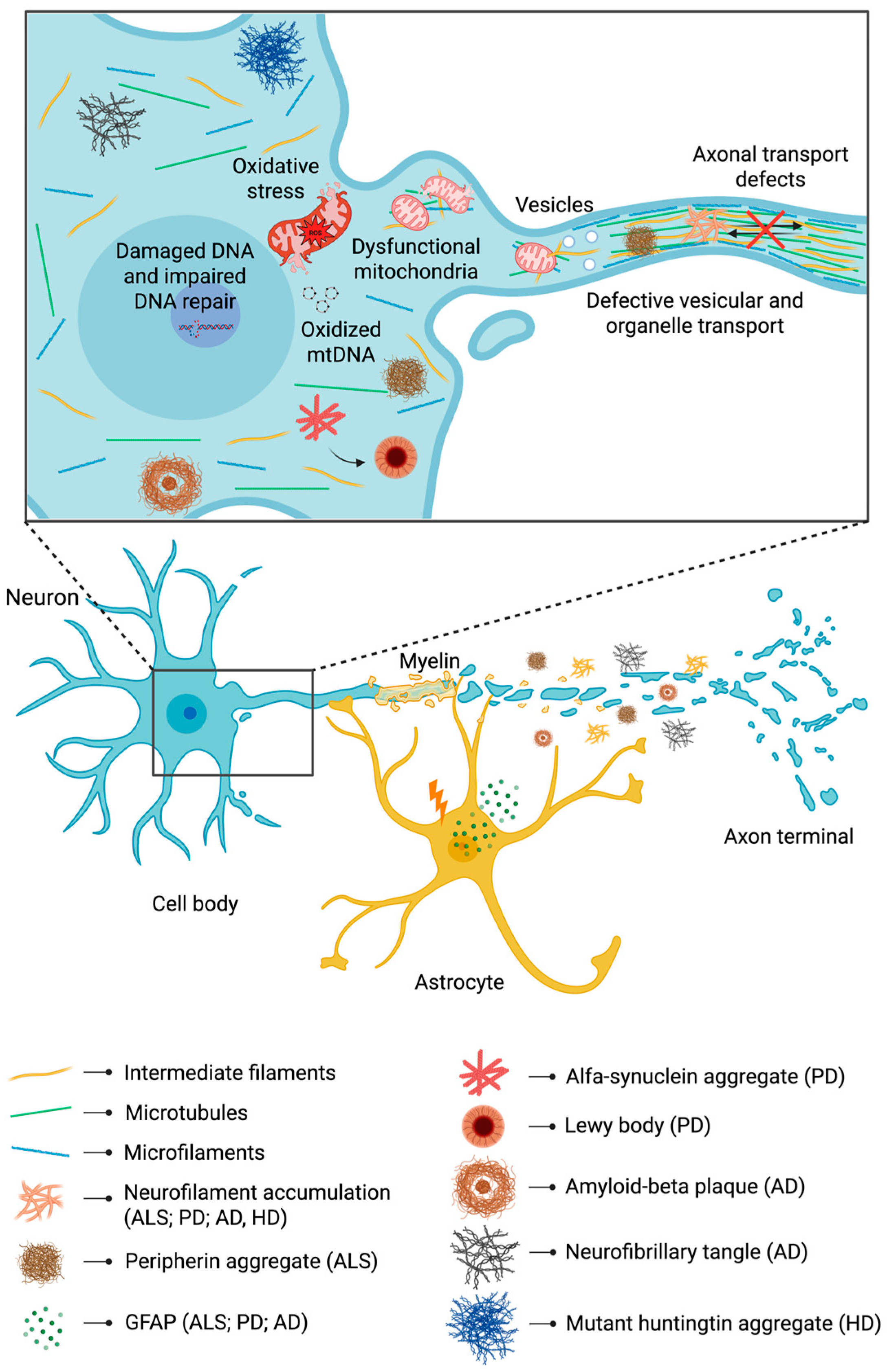

5. From Cytoskeletal Disturbance to Energy Deficits: Implications of Intermediate Filaments in Neurodegeneration

5.1. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

5.2. Parkinson’s Disease

5.3. Alzheimer’s Disease

5.4. Huntington’s Disease

| Disease | Cytoskeletal/IFs Alterations and Protein Aggregates Fromation | Mitochondrial Defects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | Overexpression of peripherin; Slowed neurofilament transport; IF inclusions that precede axonal spheroids | Mitophagy defects; Lysosomal alterations; Accumulation of damaged organelles; Impaired mitochondrial turnover | [155,166] |

| Parkinson’s disease | Aggregation of α-synuclein; Alters cell morphology and likely associated cytoskeleton (microtubules, secondary IFs) | Reduced mitochondrial respiration; Oxidative stress; Membrane potential loss; Impaired mitochondrial quality | [183] |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Pathological tau spreads and interacts with microtubules and secondary IFs; Intracellular transport of organelles and proteins impaired by tau and Aβ aggregates | Mitochondrial transport defects in dendrites; Mitochondrial fragmentation; Dynamin-related protein 1 activation; Increased reactive oxygen species | [195] |

| Huntington’s disease | Mutant huntingtin aggregates; Accumulation around inclusions; Interference with cytoskeletal trafficking; Cytoskeletal disorganization implicated in transport block | Reduced mitochondrial mobility; Altered morphology (cristae, size); Fragmented mitochondrial network | [203] |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eldeeb, M.A.; Thomas, R.A.; Ragheb, M.A.; Fallahi, A.; Fon, E.A. Mitochondrial quality control in health and in Parkinson’s disease. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1721–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominiak, A.; Gawinek, E.; Banaszek, A.A.; Wilkaniec, A. Mitochondrial quality control in neurodegeneration and cancer: A common denominator, distinct therapeutic challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Deng, J.; Dong, J.; Liu, J.; Bigio, E.H.; Mesulam, M.; Wang, T.; Sun, L.; Wang, L.; Lee, A.Y.L.; et al. TDP-43 induces mitochondrial damage and activates the mitochondrial unfolded protein response. PLoS Genet. 2019, 15, e1007947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugarli, E.I.; Langer, T. Mitochondrial quality control: A matter of life and death for neurons. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 1336–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burté, F.; Carelli, V.; Chinnery, P.F.; Yu-Wai-Man, P. Disturbed mitochondrial dynamics and neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norat, P.; Soldozy, S.; Sokolowski, J.D.; Gorick, C.M.; Kumar, J.S.; Chae, Y.; Yağmurlu, K.; Prada, F.; Walker, M.; Levitt, M.R.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurological disorders: Exploring mitochondrial transplantation. NPJ Regen. Med. 2020, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.L.; Lung, H.L.; Wu, K.C.; Le, A.H.P.; Tang, H.M.; Fung, M.C. Vimentin supports mitochondrial morphology and organization. Biochem. J. 2008, 410, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, J.; Bowden, P.E.; Coulombe, P.A.; Langbein, L.; Lane, E.B.; Magin, T.M.; Maltais, L.; Omary, M.B.; Parry, D.A.D.; Rogers, M.A.; et al. New consensus nomenclature for mammalian keratins. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toivola, D.M.; Tao, G.Z.; Habtezion, A.; Liao, J.; Omary, M.B. Cellular integrity plus: Organelle-related and protein-targeting functions of intermediate filaments. Trends Cell Biol. 2005, 15, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwatsuki, H.; Suda, M. Seven kinds of intermediate filament networks in the cytoplasm of polarized cells: Structure and function. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 2010, 43, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lépinoux-Chambaud, C.; Eyer, J. Review on intermediate filaments of the nervous system and their pathological alterations. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 140, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, L.M.; Kerr, J.P.; Lupinetti, J.; Zhang, Y.; Russell, M.A.; Bloch, R.J.; Bond, M. Synemin isoforms differentially organize cell junctions and desmin filaments in neonatal cardiomyocytes. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalczyk, K.; Ziman, M. Nestin structure and predicted function in cellular cytoskeletal organisation. Histol. Histopathol. 2005, 20, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, S.; Viedma-Poyatos, Á.; Navarro-Carrasco, E.; Martínez, A.E.; Pajares, M.A.; Pérez-Sala, D. Vimentin filaments interact with the actin cortex in mitosis allowing normal cell division. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokhadar, Š.Z.; Stojković, B.; Vidak, M.; Sorčan, T.; Liovic, M.; Gouveia, M.; Travasso, R.D.M.; Derganc, J. Cortical stiffness of keratinocytes measured by lateral indentation with optical tweezers. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiaye, A.B.; Koenderink, G.H.; Shemesh, M. Intermediate filaments in cellular mechanoresponsiveness: Mediating cytoskeletal crosstalk from membrane to nucleus and back. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 882037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenvall, C.G.A.; Nyström, J.H.; Butler-Hallissey, C.; Jansson, T.; Heikkilä, T.R.H.; Adam, S.A.; Foisner, R.; Goldman, R.D.; Ridge, K.M.; Toivola, D.M. Cytoplasmic keratins couple with and maintain nuclear envelope integrity in colonic epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2022, 33, ar121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.; Zhou, B.; Bewersdorf, L.; Schwarz, N.; Schacht, G.M.; Boor, P.; Hoeft, K.; Hoffmann, B.; Fuchs, E.; Kramann, R.; et al. Desmoplakin maintains transcellular keratin scaffolding and protects from intestinal injury. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 13, 1181–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Worman, H.J. Structural organization of the human gene (LMNB1) encoding nuclear lamin B1. Genomics 1995, 27, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, S.; Coll-Bonfill, N.; Teodoro-Castro, B.; Kuppa, S.; Jackson, J.; Shashkova, E.; Mahajan, U.; Vindigni, A.; Antony, E.; Gonzalo, S. Lamin A/C recruits ssDNA protective proteins RPA and RAD51 to stalled replication forks to maintain fork stability. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulielmos, G.; Gounari, F.; Remington, S.; Müller, S.; Häner, M.; Aebi, U.; Georgatos, S.D. Filensin and phakinin form a novel type of beaded intermediate filaments and coassemble de novo in cultured cells. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 132, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanghvi-Shah, R.; Weber, G.F. Intermediate filaments at the junction of mechanotransduction, migration, and development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, N.; Leube, R.E. Intermediate filaments as organizers of cellular space: How they affect mitochondrial structure and function. Cells 2016, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alieva, I.B.; Shakhov, A.S.; Dayal, A.A.; Churkina, A.S.; Parfenteva, O.I.; Minin, A.A. Unique role of vimentin in the intermediate filament proteins family. Biochem. Mosc. 2024, 89, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.L.; Hollenbeck, P.J. Axonal transport of mitochondria along microtubules and F-actin in living vertebrate neurons. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 131, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, H.; Aebi, U. Intermediate filaments: Molecular structure, assembly mechanism, and integration into functionally distinct intracellular scaffolds. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004, 73, 749–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzetti, E.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Calvani, R.; Pesce, V.; Landi, F.; Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Picca, A. From cell architecture to mitochondrial signaling: Role of intermediate filaments in health, aging, and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; Del Fiore, V.S.; Bucci, C. Role of the intermediate filament protein peripherin in health and disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mose-Larsen, P.; Bravo, R.; Fey, S.J.; Small, J.V.; Celis, J.E. Putative association of mitochondria with a subpopulation of intermediate-sized filaments in cultured human skin fibroblasts. Cell 1982, 31, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, D.J.; Mavroidis, M.; Weisleder, N.; Capetanaki, Y. Desmin cytoskeleton linked to muscle mitochondrial distribution and respiratory function. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 150, 1283–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, O.I.; Lifshitz, J.; Janmey, P.A.; Linden, M.; McIntosh, T.K.; Leterrier, J.F. Mechanisms of mitochondria-neurofilament interactions. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 9046–9058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Casafuz, A.B.; De Rossi, M.C.; Bruno, L. Mitochondrial cellular organization and shape fluctuations are differentially modulated by cytoskeletal networks. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4065, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7543. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34566-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, P.; Zhao, L.; Tao, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yu, B.; Zhu, J.; et al. Gas5 inhibition promotes the axon regeneration in the adult mammalian nervous system. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 356, 114157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Luan, Z. Identifying genes that affect differentiation of human neural stem cells and myelination of mature oligodendrocytes. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 2337–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragona, M.; Porcino, C.; Briglia, M.; Mhalhel, K.; Abbate, F.; Levanti, M.; Montalbano, G.; Laurà, R.; Lauriano, E.R.; Germanà, A.; et al. Vimentin localization in the zebrafish oral cavity: A potential role in taste buds regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, L.; Abrahamsberg, C.; Wiche, G. Plectin isoform 1b mediates mitochondrion-intermediate filament network linkage and controls organelle shape. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 181, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezniczek, G.A.; Abrahamsberg, C.; Fuchs, P.; Spazierer, D.; Wiche, G. Plectin 5′-transcript diversity: Short alternative sequences determine stability of gene products, initiation of translation and subcellular localization of isoforms. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 3181–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekrasova, O.E.; Mendez, M.G.; Chernoivanenko, I.S.; Tyurin-Kuzmin, P.A.; Kuczmarski, E.R.; Gelfand, V.I.; Goldman, R.D.; Minin, A.A. Vimentin intermediate filaments modulate the motility of mitochondria. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 2282–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveeva, E.A.; Venkova, L.S.; Chernoivanenko, I.S.; Minin, A.A. Vimentin is involved in regulation of mitochondrial motility and membrane potential by Rac1. Biol. Open 2015, 4, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstonog, G.V.; Belichenko-Weitzmann, I.V.; Lu, J.P.; Hartig, R.; Shoeman, R.L.; Traub, U.; Traub, P. Spontaneously immortalized mouse embryo fibroblasts: Growth behavior of wild-type and vimentin-deficient cells in relation to mitochondrial structure and activity. DNA Cell Biol. 2005, 24, 680–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.V.; Javadov, S.; Grimm, M.; Margreiter, R.; Ausserlechner, M.J.; Hagenbuchner, J. Crosstalk between mitochondria and cytoskeleton in cardiac cells. Cells 2020, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernoivanenko, I.S.; Matveeva, E.A.; Gelfand, V.I.; Goldman, R.D.; Minin, A.A. Mitochondrial membrane potential is regulated by vimentin intermediate filaments. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, A.A.; Parfenteva, O.I.; Wang, H.; Gebreselase, B.A.; Gyoeva, F.K.; Alieva, I.B.; Minin, A.A. Vimentin intermediate filaments maintain membrane potential of mitochondria in growing neurites. Biology 2024, 13, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izawa, I.; Inagaki, M. Regulatory mechanisms and functions of intermediate filaments: A study using site- and phosphorylation state-specific antibodies. Cancer Sci. 2006, 97, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostareva, A.; Sjöberg, G.; Bruton, J.; Zhang, S.J.; Balogh, J.; Gudkova, A.; Hedberg, B.; Edström, L.; Westerblad, H.; Sejersen, T. Mice expressing L345P Mutant desmin exhibit morphological and functional changes of skeletal and cardiac mitochondria. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 2008, 29, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Ling, S.; Yu, X.D.; Venkatesh, L.K.; Subramanian, T.; Chinnadurai, G.; Kuo, T.H. Modulation of mitochondrial Ca2+ homeostasis by Bcl-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 33267–33273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendelin, M.; Lemba, M.; Saks, V.A. Analysis of functional coupling: Mitochondrial creatine kinase and adenine nucleotide translocase. Biophys. J. 2004, 87, 696–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hol, E.M.; Capetanaki, Y. Type III intermediate filaments desmin, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), vimentin, and peripherin. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017, 9, a021642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Der Perng, M.; Wen, S.F.; Gibbon, T.; Middeldorp, J.; Sluijs, J.; Hol, E.M.; Quinlan, R.A. Glial fibrillary acidic protein filaments can tolerate the incorporation of assembly-compromised GFAP-delta, but with consequences for filament organization and alphaB-crystallin association. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 4521–4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasson, C.; Sahlgren, C.; Berthold, C.H.; Stakeberg, J.; Celis, J.E.; Betsholtz, C.; Eriksson, J.E.; Pekny, M. Intermediate filament protein partnership in astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 23996–24006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hol, E.M.; Pekny, M. Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and the astrocyte intermediate filament system in diseases of the central nervous system. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 32, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, U.; Sridhar, S.; Kaushik, S.; Kiffin, R.; Cuervo, A.M. Identification of regulators of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Mol. Cell 2010, 39, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dice, J.F. Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy 2007, 3, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsson, U.; Faiz, M.; De Pablo, Y.; Sjöqvist, M.; Andersson, D.; Widestrand, Å.; Potokar, M.; Stenovec, M.; Smith, P.L.P.; Shinjyo, N.; et al. Astrocytes negatively regulate neurogenesis through the Jagged1-mediated Notch pathway. Stem Cells 2012, 30, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.G.; Robinson, M.B. Reciprocal regulation of mitochondrial dynamics and calcium signaling in astrocyte processes. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 15199–15213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, T.L.; Higgs, N.F.; Sheehan, D.F.; Al Awabdh, S.; López-Doménech, G.; Arancibia-Carcamo, I.L.; Kittler, J.T. Miro1 regulates activity-driven positioning of mitochondria within astrocytic processes apposed to synapses to regulate intracellular calcium signaling. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 15996–16011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, R.A.; Brenner, M.; Goldman, J.E.; Messing, A. GFAP and its role in Alexander disease. Exp. Cell Res. 2007, 313, 2077–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, J.; Pei, G. Mitochondria are dynamically transferring between human neural cells and alexander disease-associated GFAP mutations impair the astrocytic transfer. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2019, 13, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griessinger, E.; Moschoi, R.; Biondani, G.; Peyron, J.-F. Mitochondrial transfer in the leukemia microenvironment. Trends Cancer 2017, 3, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralba, D.; Baixauli, F.; Sánchez-Madrid, F. Mitochondria know no boundaries: Mechanisms and functions of intercellular mitochondrial transfer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 4, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, L.; Capobianco, D.L.; Di Palma, F.; Binda, E.; Legnani, F.G.; Vescovi, A.L.; Svelto, M.; Pisani, F. GFAP serves as a structural element of tunneling nanotubes between glioblastoma cells and could play a role in the intercellular transfer of mitochondria. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1221671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, A.; Rao, M.V.; Sasaki, T.; Chen, Y.; Kumar, A.; Veeranna; Liem, R.K.H.; Eyer, J.; Peterson, A.C.; Julien, J.P.; et al. Alpha-internexin is structurally and functionally associated with the neurofilament triplet proteins in the mature CNS. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 10006–10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkcaldie, M.T.K.; Dwyer, S.T. The third wave: Intermediate filaments in the maturing nervous system. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2017, 84, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomont, P. The Dazzling Rise of Neurofilaments: Physiological functions and roles as biomarkers. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2021, 68, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.V.; Garcia, M.L.; Miyazaki, Y.; Gotow, T.; Yuan, A.; Mattina, S.; Ward, C.M.; Calcutt, N.A.; Uchiyama, Y.; Nixon, R.A.; et al. Gene replacement in mice reveals that the heavily phosphorylated tail of neurofilament heavy subunit does not affect axonal caliber or the transit of cargoes in slow axonal transport. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 158, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szebenyi, G.; Smith, G.M.; Li, P.; Brady, S.T. Overexpression of neurofilament h disrupts normal cell structure and function. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 68, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hisanaga, S.-i.; Hirokawa, N. Structure of the peripheral domains of neurofilaments revealed by low angle rotary shadowing. J. Mol. Biol. 1988, 202, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julien, J.P.; Mushynski, W.E. The distribution of phosphorylation sites among identified proteolytic fragments of mammalian neurofilaments. J. Biol. Chem. 1983, 258, 4019–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leterrier, J.F.; Rusakov, D.A.; Nelson, B.D.; Linden, M. Interactions between brain mitochondria and cytoskeleton: Evidence for specialized outer membrane domains involved in the association of cytoskeleton-associated proteins to mitochondria in situ and in vitro. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1994, 27, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentil, B.J.; Minotti, S.; Beange, M.; Baloh, R.H.; Julien, J.; Durham, H.D. Normal role of the low-molecular-weight neurofilament protein in mitochondrial dynamics and disruption in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 1194–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, R.; Julien, J.-P. Real-time imaging reveals defects of fast axonal transport induced by disorganization of intermediate filaments. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 3213–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlees, J.; Ackerley, S.; Grierson, A.J.; Jacobsen, N.J.O.; Shea, K.; Anderton, B.H.; Leigh, P.N.; Shaw, C.E.; Miller, C.C.J. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease neurofilament mutations disrupt neurofilament assembly and axonal transport. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 2837–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misko, A.; Jiang, S.; Wegorzewska, I.; Milbrandt, J.; Baloh, R.H. Mitofusin 2 is necessary for transport of axonal mitochondria and interacts with the Miro/Milton complex. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 4232–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpov, V.; Landon, F.; Djabali, K.; Gros, F.; Portier, M.M. Structure of the mouse gene encoding peripherin: A neuronal intermediate filament protein. Biol. Cell 1992, 76, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, M.A.; Ziff, E.B. Structure of the gene encoding peripherin, an NGF-regulated neuronal-specific Type III intermediate filament protein. Neuron 1989, 2, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, J.; Ley, C.A.; Parysek, L.M. The structure of the human peripherin gene (PRPH) and identification of potential regulatory elements. Genomics 1994, 22, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landon, F.; Lemonnier, M.; Benarous, R.; Huc, C.; Fiszman, M.; Gros, F.; Portier, M.M. Multiple mRNAs encode peripherin, a neuronal intermediate filament protein. EMBO J. 1989, 8, 1719–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, J.; Xiao, S.; Miyazaki, K.; Robertson, J. A Novel peripherin isoform generated by alternative translation is required for normal filament network formation. J. Neurochem. 2008, 104, 1663–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Tjostheim, S.; Sanelli, T.; McLean, J.R.; Horne, P.; Fan, Y.; Ravits, J.; Strong, M.J.; Robertson, J. An aggregate-inducing peripherin isoform generated through intron retention is upregulated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and associated with disease pathology. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portier, M.M.; Brachet, P.; Croizat, B.; Gros, F. Regulation of peripherin in mouse neuroblastoma and rat PC 12 pheochromocytoma cell lines. Dev. Neurosci. 1983, 6, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parysek, L.M.; Goldman, R.D. Distribution of a novel 57 kDa intermediate filament (IF) protein in the nervous system. J. Neurosci. 1988, 8, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, D.G.B.; Gorham, J.D.; Cole, P.; Greene, L.A.; Ziff, E.B. A Nerve growth factor-regulated messenger RNA encodes a new intermediate filament protein. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 106, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parysek, L.M.; McReynolds, M.A.; Goldman, R.D.; Ley, C.A. Some neural intermediate filaments contain both peripherin and the neurofilament proteins. J. Neurosci. Res. 1991, 30, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, A.; Sasaki, T.; Kumar, A.; Peterhoff, C.M.; Rao, M.V.; Liem, R.K.; Julien, J.P.; Nixon, R.A. Peripherin is a subunit of peripheral nerve neurofilaments: Implications for differential vulnerability of CNS and peripheral nervous system axons. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 8501–8508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.M.; Nguyen, M.D.; Julien, J.P. Late onset of motor neurons in mice overexpressing wild-type peripherin. J. Cell Biol. 1999, 147, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.M.; Julien, J.P. Peripherin-mediated death of motor neurons rescued by overexpression of neurofilament NF-H proteins. J. Neurochem. 2003, 85, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.V.; Flanagan, L.A.; Janmey, P.A.; Leterrier, J.F. Bidirectional translocation of neurofilaments along microtubules mediated in part by dynein/dynactin. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 11, 3495–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabe, J.T.; Pimenta, A.; Shea, T.B. Kinesin-mediated transport of neurofilament protein oligomers in growing axons. J. Cell Sci. 1999, 112 Pt 21, 3799–3814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Oblinger, M.M. Differential regulation of peripherin and neurofilament gene expression in regenerating rat DRG Nneurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 1990, 27, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddie, S.; Smyth, D.; Keh, R.Y.S.; Chou, M.K.L.; Grant, D.; Surana, S.; Heslegrave, A.; Zetterberg, H.; Wieske, L.; Michael, M.; et al. Peripherin is a biomarker of axonal damage in peripheral nervous system disease. Brain 2023, 146, 4562–4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, T.; Yue, L.; Longlong, Z.; Longda, M.; Fang, H.; Yehui, L.; Yang, L.; Yiwu, Z. Peripherin: A proposed biomarker of traumatic axonal injury triggered by mechanical force. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2023, 58, 3206–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, W.T.; Edwards, B.; McCullagh, K.J.A.; Kemp, M.W.; Moorwood, C.; Sherman, D.L.; Burgess, M.; Davies, K.E. Syncoilin modulates peripherin filament networks and is necessary for large-calibre motor neurons. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 2543–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helfand, B.T.; Mendez, M.G.; Pugh, J.; Delsert, C.; Goldman, R.D. A Role for intermediate filaments in determining and maintaining the shape of nerve cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 5069–5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larivière, R.C.; Nguyen, M.D.; Ribeiro-Da-Silva, A.; Julien, J.P. Reduced number of unmyelinated sensory axons in peripherin null mice. J. Neurochem. 2002, 81, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.C.; Thorne, P.R.; Housley, G.D.; Montgomery, J.M. Spatiotemporal definition of neurite outgrowth, refinement and retraction in the developing mouse cochlea. Development 2007, 134, 2925–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.C.; Barclay, M.; Lee, K.; Peter, S.; Housley, G.D.; Thorne, P.R.; Montgomery, J.M. Synaptic profiles during neurite extension, refinement and retraction in the developing cochlea. Neural Dev. 2012, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, V.; Villegas, C.; Muresan, Z.L. Functional interaction between amyloid-β precursor protein and peripherin neurofilaments: A shared pathway leading to Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Neurodegener. Dis. 2014, 13, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, V.; Muresan, Z.L. Shared molecular mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Neurofilament-dependent transport of SAPP, FUS, TDP-43 and SOD1, with endoplasmic reticulum-like tubules. Neurodegener. Dis. 2016, 16, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogli, L.; Progida, C.; Thomas, C.L.; Spencer-Dene, B.; Donno, C.; Schiavo, G.; Bucci, C. Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2B disease-causing RAB7A mutant proteins show altered interaction with the neuronal intermediate filament peripherin. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 125, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathasivam, S.; Ince, P.G.; Shaw, P.J. Apoptosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A review of the evidence. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2001, 27, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunesson, L.; Hellman, U.; Larsson, C. Protein kinase Cε binds peripherin and induces its aggregation, which is accompanied by apoptosis of neuroblastoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 16653–16664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konishi, H.; Namikawa, K.; Shikata, K.; Kobatake, Y.; Tachibana, T.; Kiyama, H. Identification of peripherin as a akt substrate in neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 23491–23499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Vicente, C.; Guerrero-Valero, M.; Nielsen, M.L.; Savitski, M.M.; Gómez-Fernández, J.C.; Zubarev, R.A.; Corbalán-García, S. ATP Enhances neuronal differentiation of PC12 Cells by activating PKCα interactions with cytoskeletal proteins. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterneck, E.; Kaplan, D.R.; Johnson, P.F. Interleukin-6 induces expression of peripherin and cooperates with Trk receptor signaling to promote neuronal differentiation in PC12 cells. J. Neurochem. 1996, 67, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.Y.; Toledo-Aral, J.J.; Lin, H.Y.; Ischenko, I.; Medina, L.; Safo, P.; Mandel, G.; Levinson, S.R.; Halegoua, S.; Hayman, M.J. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 induces gene expression primarily through ras-independent signal transduction pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 5116–5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, D.G.B.; Ziff, E.B.; Greene, L.A. Identification and characterization of mRNAs regulated by nerve growth factor in PC12 cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987, 7, 3156–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, J.E. MAM (mitochondria-associated membranes) in mammalian cells: Lipids and beyond. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1841, 595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achleitner, G.; Gaigg, B.; Krasser, A.; Kainersdorfer, E.; Kohlwein, S.D.; Perktold, A.; Zellnig, G.; Daum, G. Association between the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria of yeast facilitates interorganelle transport of phospholipids through membrane contact. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999, 264, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippin, L.; Magalhães, P.J.; Di Benedetto, G.; Colella, M.; Pozzan, T. Stable interactions between mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum allow rapid accumulation of calcium in a subpopulation of mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 39224–39234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabadkai, G.; Bianchi, K.; Várnai, P.; De Stefani, D.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Cavagna, D.; Nagy, A.I.; Balla, T.; Rizzuto, R. Chaperone-mediated coupling of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial Ca2+ channels. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 175, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, C.; Miller, R.A.; Smith, I.; Bui, T.; Molgó, J.; Müller, M.; Vais, H.; Cheung, K.H.; Yang, J.; Parker, I.; et al. Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell 2010, 142, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, S.; Narita, M.; Tsujimoto, Y. Bcl-2 family proteins regulate the release of apoptogenic cytochrome c by the mitochondrial channel VDAC. Nature 1999, 399, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlattner, U.; Tokarska-Schlattner, M.; Rousseau, D.; Boissan, M.; Mannella, C.; Epand, R.; Lacombe, M.L. Mitochondrial cardiolipin/phospholipid trafficking: The role of membrane contact site complexes and lipid transfer proteins. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2014, 179, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishizawa, M.; Izawa, I.; Inoko, A.; Hayashi, Y.; Nagata, K.I.; Yokoyama, T.; Usukura, J.; Inagaki, M. Identification of trichoplein, a novel keratin filament-binding protein. J. Cell Sci. 2005, 118, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqua, C.; Anesti, V.; Pyakurel, A.; Liu, D.; Naon, D.; Wiche, G.; Baffa, R.; Dimmer, K.S.; Scorrano, L. Trichoplein/mitostatin regulates endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria juxtaposition. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Bouameur, J.E.; Bär, J.; Rice, R.H.; Hornig-Do, H.T.; Roop, D.R.; Schwarz, N.; Brodesser, S.; Thiering, S.; Leube, R.E.; et al. A keratin scaffold regulates epidermal barrier formation, mitochondrial lipid composition, and activity. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 211, 1057–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, E.; Griparic, L.; Shurland, D.L.; Van der Bliek, A.M. Dynamin-related protein Drp1 is required for mitochondrial division in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 2245–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.I.; Parone, P.A.; Mattenberger, Y.; Martinou, J.C. HFis1, a novel component of the mammalian mitochondrial fission machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 36373–36379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandre-Babbe, S.; Van Der Bliek, A.M. The novel tail-anchored membrane protein Mff controls mitochondrial and peroxisomal fission in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 2402–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santel, A.; Fuller, M.T. Control of mitochondrial morphology by a human mitofusin. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolat, S.; De Brito, O.M.; Dal Zilio, B.; Scorrano, L. OPA1 requires mitofusin 1 to promote mitochondrial fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 15927–15932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, A.; Son, S.; Baek, Y.M.; Kim, D.E. KRT8 (keratin 8) attenuates necrotic cell death by facilitating mitochondrial fission-mediated mitophagy through interaction with plec (plectin). Autophagy 2021, 17, 3939–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anesti, V.; Scorrano, L. The relationship between mitochondrial shape and function and the cytoskeleton. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1757, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.S.; Holzbaur, E.L. Mitochondrial-cytoskeletal interactions: Dynamic associations that facilitate network function and remodeling. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2018, 3, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mónico, A.; Duarte, S.; Pajares, M.A.; Pérez-Sala, D. Vimentin Disruption by Lipoxidation and Electrophiles: Role of the Cysteine Residue and Filament Dynamics. Redox Biol. 2019, 23, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaus-Drobek, M.; Mücke, N.; Szczepanowski, R.H.; Wedig, T.; Czarnocki-Cieciura, M.; Polakowska, M.; Herrmann, H.; Wysłouch-Cieszyńska, A.; Dadlez, M. Vimentin S-glutathionylation at Cys328 inhibits filament elongation and induces severing of mature filaments in vitro. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 5304–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lois-Bermejo, I.; González-Jiménez, P.; Duarte, S.; Pajares, M.A.; Pérez-Sala, D. Vimentin tail segments are differentially exposed at distinct cellular locations and in response to stress. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 908263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesser, E.; Vemula, V.; Mónico, A.; Pérez-Sala, D.; Fedorova, M. Dynamic posttranslational modifications of cytoskeletal proteins unveil hot spots under nitroxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2021, 44, 102014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Schweppe, D.K.; Huttlin, E.L.; Yu, Q.; Heppner, D.E.; Li, J.; Long, J.; Mills, E.L.; Szpyt, J.; et al. A quantitative tissue-specific landscape of protein redox regulation during aging. Cell 2020, 180, 968–983.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sala, D.; Oeste, C.L.; Martínez, A.E.; Carrasco, M.J.; Garzón, B.; Cañada, F.J. Vimentin filament organization and stress sensing depend on its single cysteine residue and zinc binding. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.N.; Toperzer, J.; Scherer, A.; Gumina, A.; Brunetti, T.; Mansour, M.K.; Markovitz, D.M.; Russo, B.C. Vimentin regulates mitochondrial ROS production and inflammatory responses of neutrophils. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1416275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håversen, L.; Sundelin, J.P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Rutberg, M.; Ståhlman, M.; Wilhelmsson, U.; Hultén, L.M.; Pekny, M.; Fogelstrand, P.; Bentzon, J.F.; et al. Vimentin deficiency in macrophages induces increased oxidative stress and vascular inflammation but attenuates atherosclerosis in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsnicova, B.; Hornikova, D.; Tibenska, V.; Kolar, D.; Tlapakova, T.; Schmid, B.; Mallek, M.; Eggers, B.; Schlötzer-Schrehardt, U.; Peeva, V.; et al. Desmin knock-out cardiomyopathy: A heart on the verge of metabolic crisis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viedma-Poyatos, Á.; González-Jiménez, P.; Pajares, M.A.; Pérez-Sala, D. Alexander disease GFAP R239C mutant shows increased susceptibility to lipoxidation and elicits mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2022, 55, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnetti, G.; Herrmann, H.; Cohen, S. New roles for desmin in the maintenance of muscle homeostasis. FEBS J. 2022, 289, 2755–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israeli, E.; Dryanovski, D.I.; Schumacker, P.T.; Chandel, N.S.; Singer, J.D.; Julien, J.P.; Goldman, R.D.; Opal, P. Intermediate filament aggregates cause mitochondrial dysmotility and increase energy demands in giant axonal neuropathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 2143–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styers, M.L.; Salazar, G.; Love, R.; Peden, A.A.; Kowalczyk, A.P.; Faundez, V. The endo-lysosomal sorting machinery interacts with the intermediate filament cytoskeleton. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 5369–5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margiotta, A.; Bucci, C. Role of intermediate filaments in vesicular traffic. Cells 2016, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, R.; Cordella, P.; Bucci, C. The type III intermediate filament protein peripherin regulates lysosomal degradation activity and autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.E.; Bucci, C.; Vieira, O.V.; Schroer, T.A.; Grinstein, S. Phagosomes fuse with late endosomes and/or lysosomes by extension of membrane protrusions along microtubules: Role of Rab7 and RILP. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 6494–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, S.; Bucci, C.; Tanida, I.; Ueno, T.; Kominami, E.; Saftig, P.; Eskelinen, E.-L. Role for Rab7 in maturation of late autophagic vacuoles. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 4837–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentil, B.J.; McLean, J.R.; Xiao, S.; Zhao, B.; Durham, H.D.; Robertson, J. A Two-hybrid screen identifies an unconventional role for the intermediate filament peripherin in regulating the subcellular distribution of the SNAP25-interacting protein, SIP30. J. Neurochem. 2014, 131, 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazell, A.S.; Wang, D. Identification of complexin ii in astrocytes: A possible regulator of glutamate release in these cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 404, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goutman, S.A.; Hardiman, O.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Chió, A.; Savelieff, M.G.; Kiernan, M.C.; Feldman, E.L. Recent advances in the diagnosis and prognosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosolini, A.P.; Sleigh, J.N.; Surana, S.; Rhymes, E.R.; Cahalan, S.D.; Schiavo, G. BDNF-dependent modulation of axonal transport is selectively impaired in ALS. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.E. A view from the ending: Axonal dieback and regeneration following SCI. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 652, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štetkárová, I.; Ehler, E. Diagnostics of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Up to date. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millecamps, S.; Julien, J.P. Axonal transport deficits and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.Z.; Hays, A.P. Expression of peripherin in ubiquinated inclusions of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2004, 217, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, C.M.; Muma, N.A.; Greene, L.A.; Price, D.L.; Shelanski, M.L. Regulation of peripherin and neurofilament expression in regenerating rat motor neurons. Brain Res. 1990, 529, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbo, M.; Hays, A.P. Peripherin and neurofilament protein coexist in spinal spheroids of motor neuron disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1992, 51, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Takatama, M.; Okamoto, K. Peripherin partially localizes in bunina bodies in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 302, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, Y.; Mori, F.; Seino, Y.; Tanji, K.; Yoshizawa, T.; Kijima, H.; Shoji, M.; Wakabayashi, K. Colocalization of Bunina bodies and TDP-43 inclusions in a case of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with Lewy body-like hyaline inclusions. Neuropathology 2018, 38, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, J.; Beaulieu, J.M.; Doroudchi, M.M.; Durham, H.D.; Julien, J.P.; Mushynski, W.E. Apoptotic death of neurons exhibiting peripherin aggregates is mediated by the proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 155, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.C.; Chen, Y.Y.; Kan, D.; Chien, C.L. A neuronal death model: Overexpression of neuronal intermediate filament protein peripherin in PC12 cells. J. Biomed. Sci. 2012, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordoni, M.; Pansarasa, O.; Scarian, E.; Cristofani, R.; Leone, R.; Fantini, V.; Garofalo, M.; Diamanti, L.; Bernuzzi, S.; Gagliardi, S.; et al. Lysosomes dysfunction causes mitophagy impairment in PBMCs of sporadic ALS patients. Cells 2022, 11, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genin, E.C.; Abou-Ali, M.; Paquis-Flucklinger, V. Mitochondria, a key target in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis pathogenesis. Genes 2023, 14, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grel, H.; Woznica, D.; Ratajczak, K.; Kalwarczyk, E.; Anchimowicz, J.; Switlik, W.; Olejnik, P.; Zielonka, P.; Stobiecka, M.; Jakiela, S. Mitochondrial dynamics in neurodegenerative diseases: Unraveling the role of fusion and fission processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, A.M.; Nguyen, M.D.; Roberts, E.A.; Garcia, M.L.; Boillée, S.; Rule, M.; McMahon, A.P.; Doucette, W.; Siwek, D.; Ferrante, R.J.; et al. Wild-type nonneuronal cells extend survival of SOD1 mutant motor neurons in ALS mice. Science 2003, 302, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.M.; Robertson, J.; Julien, J.P. Interactions between peripherin and neurofilaments in cultured cells: Disruption of peripherin assembly by the NF-M and NF-H subunits. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1999, 77, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, J.M.; Jacomy, H.; Julien, J.P. Formation of intermediate filament protein aggregates with disparate effects in two transgenic mouse models lacking the neurofilament light subunit. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 5321–5328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawley, Z.C.E.; Campos-Melo, D.; Strong, M.J. MiR-105 and MiR-9 Regulate the mRNA stability of neuronal intermediate filaments. implications for the pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Brain Res. 2019, 1706, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado, L.; Carlomagno, Y.; Falasco, L.; Mellone, S.; Godi, M.; Cova, E.; Cereda, C.; Testa, L.; Mazzini, L.; D’Alfonso, S. A novel peripherin gene (PRPH) mutation identified in one sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient. Neurobiol. Aging 2011, 32, 552.e1–552.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gros-Louis, F.; Larivière, R.; Gowing, G.; Laurent, S.; Camu, W.; Bouchard, J.P.; Meininger, V.; Rouleau, G.A.; Julien, J.P. A frameshift deletion in peripherin gene associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 45951–45956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.L.; He, C.Z.; Kaufmann, P.; Chin, S.S.; Naini, A.; Liem, R.K.H.; Mitsumoto, H.; Hays, A.P. A pathogenic peripherin gene mutation in a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2004, 14, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Doroudchi, M.M.; Nguyen, M.D.; Durham, H.D.; Strong, M.J.; Shaw, G.; Julien, J.P.; Mushynski, W.E. A neurotoxic peripherin splice variant in a mouse model of ALS. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 160, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millecamps, S.; Robertson, J.; Lariviere, R.; Mallet, J.; Julien, J.P. Defective axonal transport of neurofilament proteins in neurons overexpressing peripherin. J. Neurochem. 2006, 98, 926–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larivière, R.C.; Beaulieu, J.M.; Nguyen, M.D.; Julien, J.P. Peripherin is not a contributing factor to motor neuron disease in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caused by mutant superoxide dismutase. Neurobiol. Dis. 2003, 13, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ching, G.Y.; Chien, C.L.; Flores, R.; Liem, R.K.H. Overexpression of alpha-internexin causes abnormal neurofilamentous accumulations and motor coordination deficits in transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 2974–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhit, R.; Chakrabartty, A. Structure, folding, and misfolding of Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1762, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhai, J.; Cañete-Soler, R.; Schlaepfer, W.W. 3′ Untranslated region in a light neurofilament (NF-L) mRNA triggers aggregation of NF-L and mutant superoxide dismutase 1 proteins in neuronal cells. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 2716–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberstadt, M.; Claßen, J.; Arendt, T.; Holzer, M. TDP-43 and cytoskeletal proteins in ALS. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 55, 3143–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, L.R.; Culver, D.G.; Tennant, P.; Davis, A.A.; Wang, M.; Castellano-Sanchez, A.; Khan, J.; Polak, M.A.; Glass, J.D. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is a distal axonopathy: Evidence in mice and man. Exp. Neurol. 2004, 185, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.A.; Southam, K.A.; Blizzard, C.A.; King, A.E.; Dickson, T.C. Axonal degeneration, distal collateral branching and neuromuscular junction architecture alterations occur prior to symptom onset in the SOD1G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2016, 76, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manco, C.; Righi, D.; Primiano, G.; Romano, A.; Luigetti, M.; Leonardi, L.; De Stefano, N.; Plantone, D. Peripherin, a new promising biomarker in neurological disorders. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2025, 61, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhak, A.; Foschi, M.; Abu-Rumeileh, S.; Yue, J.K.; D’Anna, L.; Huss, A.; Oeckl, P.; Ludolph, A.C.; Kuhle, J.; Petzold, A.; et al. Blood GFAP as an emerging biomarker in brain and spinal cord disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 18, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, K.K.W. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: From intermediate filament assembly and gliosis to neurobiomarker. Trends Neurosci. 2015, 38, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benninger, F.; Glat, M.J.; Offen, D.; Steiner, I. Glial fibrillary acidic protein as a marker of astrocytic activation in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 26, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde, F.; Milone, I.; Maranzano, A.; Colombo, E.; Torre, S.; Solca, F.; Doretti, A.; Gentile, F.; Manini, A.; Bonetti, R.; et al. Serum levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2023, 10, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeckl, P.; Weydt, P.; Steinacker, P.; Anderl-Straub, S.; Nordin, F.; Volk, A.E.; Diehl-Schmid, J.; Andersen, P.M.; Kornhuber, J.; Danek, A.; et al. Different neuroinflammatory profile in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia is linked to the clinical phase. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2019, 90, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falzone, Y.M.; Domi, T.; Mandelli, A.; Pozzi, L.; Schito, P.; Russo, T.; Barbieri, A.; Fazio, R.; Volontè, M.A.; Magnani, G.; et al. Integrated evaluation of a panel of neurochemical biomarkers to optimize diagnosis and prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2022, 29, 1930–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrangelo, A.; Vacchiano, V.; Zenesini, C.; Ruggeri, E.; Baiardi, S.; Cherici, A.; Avoni, P.; Polischi, B.; Santoro, F.; Capellari, S.; et al. Amyloid-beta co-pathology is a major determinant of the elevated plasma GFAP values in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J.E.; Yen, S.H.; Chiu, F.C.; Peress, N.S. Lewy bodies of Parkinson’s disease contain neurofilament antigens. Science 1983, 221, 1082–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geibl, F.F.; Henrich, M.T.; Xie, Z.; Zampese, E.; Ueda, J.; Tkatch, T.; Wokosin, D.L.; Nasiri, E.; Grotmann, C.A.; Dawson, V.L.; et al. α-synuclein pathology disrupts mitochondrial function in dopaminergic and cholinergic neurons at-risk in Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schapira, A.H.V.; Cooper, J.M.; Dexter, D.; Clark, J.B.; Jenner, P.; Marsden, C.D. Mitochondrial complex I deficiency in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 1990, 54, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, V.; Junn, E.; Mouradian, M.M. The role of oxidative stress in Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2013, 3, 461–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger, R.; Fischer, C.; Schulte, T.; Strauss, K.M.; Müller, T.; Woitalla, D.; Berg, D.; Hungs, M.; Gobbele, R.; Berger, K.; et al. Mutation analysis of the neurofilament M gene in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2003, 351, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacioglu, M.; Maia, L.F.; Preische, O.; Schelle, J.; Apel, A.; Kaeser, S.A.; Schweighauser, M.; Eninger, T.; Lambert, M.; Pilotto, A.; et al. Neurofilament light chain in blood and CSF as marker of disease progression in mouse models and in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron 2016, 91, 56–66, Erratum in Neuron 2016, 91, 494–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2016.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, G.; Picca, A.; Boldrini, S.; Bove, F.; Marzetti, E.; Petracca, M.; Piano, C.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Calabresi, P. Differential profiles of serum cytokines in Parkinson’s disease according to disease duration. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 190, 106371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarakonda, S.S.; Basha, S.; Pithakumar, A.; Thoshna, L.B.; Mukunda, D.C.; Rodrigues, J.; Ameera, K.; Biswas, S.; Pai, A.R.; Belurkar, S.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of neurofilament alterations and its application in assessing neurodegenerative disorders. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 102, 102566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ning, F.; Wang, G.; Xie, A. Longitudinal correlation of cerebrospinal fluid GFAP and the progression of cognition decline in different clinical subtypes of Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e70111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilotto, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Lupini, A.; Battaglio, B.; Zatti, C.; Trasciatti, C.; Gipponi, S.; Cottini, E.; Grossi, I.; Salvi, A.; et al. Plasma NfL, GFAP, amyloid, and p-tau species as prognostic biomarkers in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 7537–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, P.; Hughes, L.; Kim, W.S.; Halliday, G.M.; Lewis, S.J.G.; Cooper, A.; Dzamko, N. Evaluation of Plasma Levels of NFL, GFAP, UCHL1 and tau as Parkinson’s disease biomarkers using multiplexed single molecule counting. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clairembault, T.; Kamphuis, W.; Leclair-Visonneau, L.; Rolli-Derkinderen, M.; Coron, E.; Neunlist, M.; Hol, E.M.; Derkinderen, P. Enteric GFAP expression and phosphorylation in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2014, 130, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauters, F.; Cornelissen, T.; Imberechts, D.; Martin, S.; Koentjoro, B.; Sue, C.; Vangheluwe, P.; Vandenberghe, W. LRRK2 mutations impair depolarization-induced mitophagy through inhibition of mitochondrial accumulation of RAB10. Autophagy 2020, 16, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Y.; Zheng, J.Q. Amyloid β oligomers elicit mitochondrial transport defects and fragmentation in a time-dependent and pathway-specific manner. Mol. Brain 2016, 9, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Zecca, C.; Chimienti, G.; Latronico, T.; Liuzzi, G.M.; Pesce, V.; Dell’Abate, M.T.; Borlizzi, F.; Giugno, A.; Urso, D.; et al. Reliable new biomarkers of mitochondrial oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma from Alzheimer’s disease patients: A pilot study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binks, S.N.M.; Graff-Radford, J. Evolving role of plasma phosphorylated tau 217 in Alzheimer disease-time for tau. JAMA Neurol. 2025, 82, 981–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.M.; Winfree, R.L.; Seto, M.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Dumitrescu, L.C.; Hohman, T.J. Pathologic and clinical correlates of region-specific brain GFAP in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 148, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.B.; Janelidze, S.; Smith, R.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N.; Palmqvist, S.; Teunissen, C.E.; Zetterberg, H.; Stomrud, E.; Ashton, N.J.; Blennow, K.; et al. Plasma GFAP is an early marker of amyloid-β but not tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2021, 144, 3505–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.Y.; Shin, K.Y.; Chang, K.A. GFAP as a potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cells 2023, 12, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellaver, B.; Povala, G.; Ferreira, P.C.L.; Bauer-Negrini, G.; Lussier, F.Z.; Leffa, D.T.; Ferrari-Souza, J.P.; Rodrigues, M.S.; Amaral, L.; Oliveira, M.S.; et al. Plasma GFAP for populational enrichment of clinical trials in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdała, A.L.; Bellomo, G.; Gaetani, L.; Toja, A.; Chipi, E.; Shan, D.; Chiasserini, D.; Parnetti, L. Trajectories of CSF and plasma biomarkers across Alzheimer’s disease continuum: Disease staging by NF-L, p-tau181, and GFAP. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 189, 106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.T.W.; Rintoul, G.L.; Pandipati, S.; Reynolds, I.J. Mutant Huntingtin aggregates impair mitochondrial movement and trafficking in cortical neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006, 22, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Solana, E.; Casado-Zueras, L.; Torres, T.E.; Goya, G.F.; Fernandez-Fernandez, M.R.; Fernandez, J.J. Disruption of the mitochondrial network in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease visualized by in-tissue multiscale 3D electron microscopy. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, L.M.; Rodrigues, F.B.; Johnson, E.B.; Wijeratne, P.A.; De Vita, E.; Alexander, D.C.; Palermo, G.; Czech, C.; Schobel, S.; Scahill, R.I.; et al. Evaluation of mutant Huntingtin and neurofilament proteins as potential markers in Huntington’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaat7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dalahmah, O.; Sosunov, A.A.; Shaik, A.; Ofori, K.; Liu, Y.; Vonsattel, J.P.; Adorjan, I.; Menon, V.; Goldman, J.E. Single-nucleus RNA-Seq identifies Huntington disease astrocyte states. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, T.G.; Thayer, M.N.; VanTreeck, J.G.; Zarate, N.; Hart, D.W.; Heilbronner, S.; Gomez-Pastor, R. Striatal spatial heterogeneity, clustering, and white matter association of GFAP+ astrocytes in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1094503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Wei, M.; Zhang, S.; Cui, H.; Dagda, R.K.; Gasanoff, E.S. Bee venom proteins enhance proton absorption by membranes composed of phospholipids of the myelin sheath and endoplasmic reticulum: Pharmacological relevance. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasanoff, E.S.; Dagda, R.K. Cobra venom cytotoxins as a tool for probing mechanisms of mitochondrial energetics and understanding mitochondrial membrane structure. Toxins 2024, 16, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marzetti, E.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Landi, F.; Pesce, V.; Picca, A. Linking Cell Architecture to Mitochondrial Signaling in Neurodegeneration: The Role of Intermediate Filaments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411852

Marzetti E, Di Lorenzo R, Calvani R, Coelho-Júnior HJ, Landi F, Pesce V, Picca A. Linking Cell Architecture to Mitochondrial Signaling in Neurodegeneration: The Role of Intermediate Filaments. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411852

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarzetti, Emanuele, Rosa Di Lorenzo, Riccardo Calvani, Hélio José Coelho-Júnior, Francesco Landi, Vito Pesce, and Anna Picca. 2025. "Linking Cell Architecture to Mitochondrial Signaling in Neurodegeneration: The Role of Intermediate Filaments" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411852

APA StyleMarzetti, E., Di Lorenzo, R., Calvani, R., Coelho-Júnior, H. J., Landi, F., Pesce, V., & Picca, A. (2025). Linking Cell Architecture to Mitochondrial Signaling in Neurodegeneration: The Role of Intermediate Filaments. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11852. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411852