Deciphering the Role of ADAMTS6 in the Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition of Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Assessment of the Role of ADAMTS6 in EMT of LUAD Cells

2.2. Verification of ADAMTS6 as a Marker of EMT in Lung Epithelial Cells

2.3. Upstream Regulators of ADAMTS6 Expression During EMT Induced by TGF-β1 and Other Factors

2.4. The Development of a CRISP/Cas9 System Targeting ADAMTS6

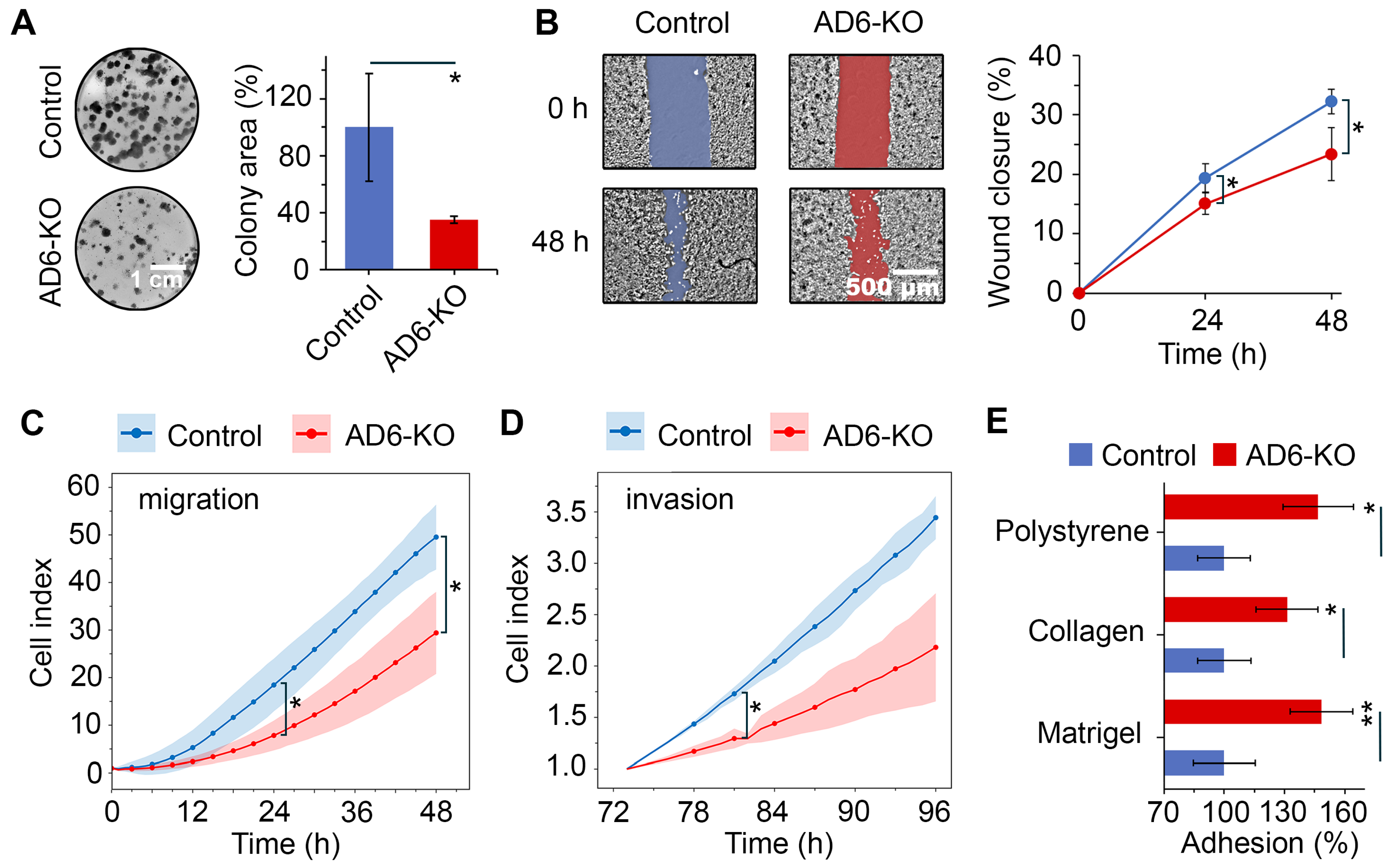

2.5. Functional Assessment of ADAMTS6 Knockout in LUAD Cells

2.6. Mechanism of EMT Mediated by ADAMTS6 Expression

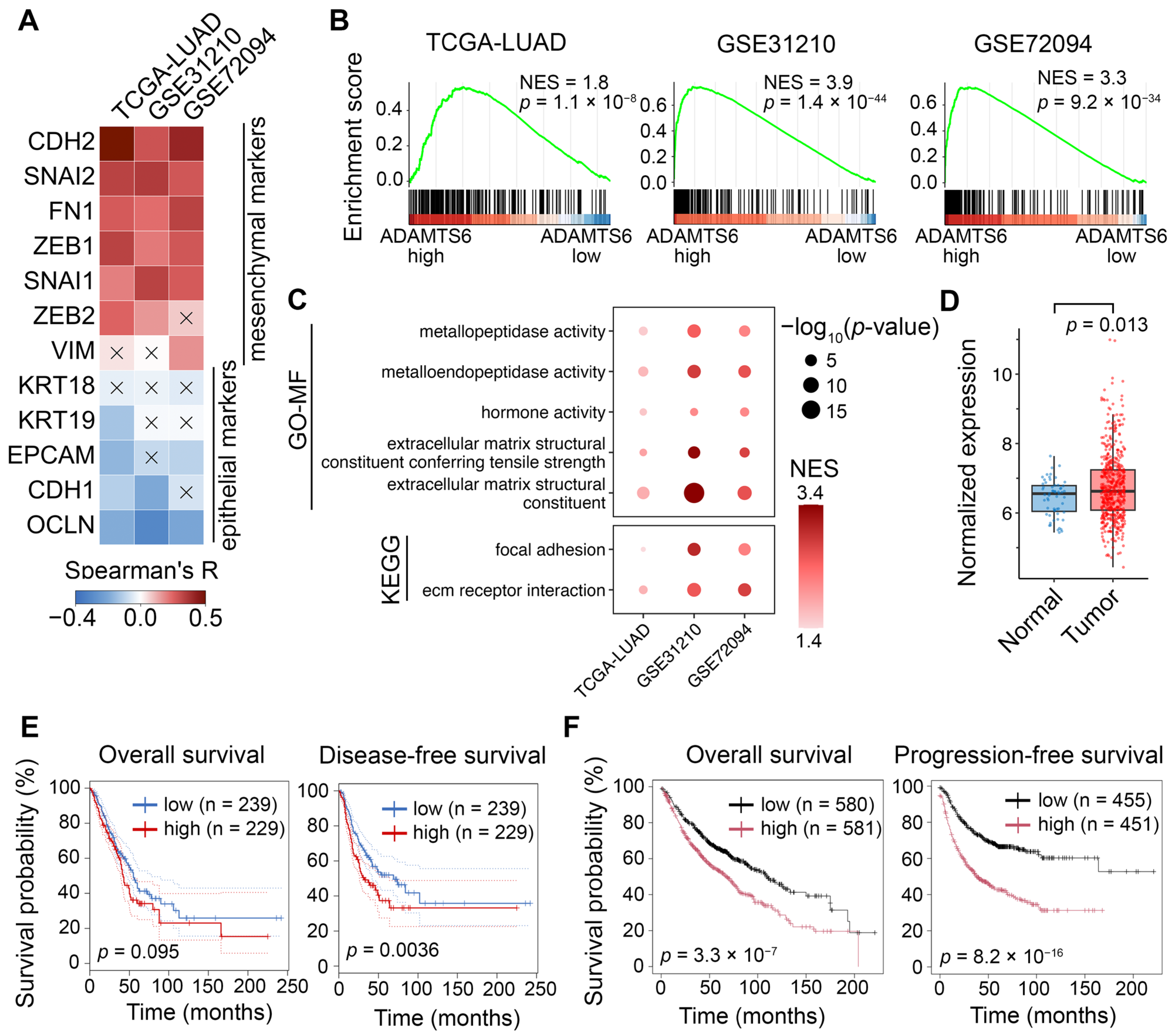

2.7. Validating Associations of ADAMTS6 with EMT in Patient Cohort

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Data Acquisition

4.3. Microarray Analysis

4.4. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

4.5. Gene Network Analysis

4.6. Text Mining

4.7. scRNA-Seq Analysis

4.8. sgRNA Design and Cloning Strategy

4.9. Cell Lines and Transfection

4.10. Verification of CRISP/Cas9-Generated Mutation

4.11. Sanger Sequencing

4.12. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

4.13. Evaluation of Cell Morphology

4.14. Cell Viability Analysis

4.15. Colony Formation

4.16. Wound Healing Assay

4.17. Transwell Assays

4.18. Adhesion Assay

4.19. Immunofluorescence

4.20. Bulk RNA-Seq Analysis

4.21. Survival Analysis

4.22. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Bao, X.; Chen, M.; Lin, R.; Zhuyan, J.; Zhen, T.; Xing, K.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, S. Mechanisms and Future of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 585284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.X.; Huang, R.Y.-J.; Sheng, G.; Thiery, J.P. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Cell 2025, 188, 5436–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, T.J. ADAMTS6: Emerging Roles in Cardiovascular, Musculoskeletal and Cancer Biology. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1023511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, N.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Mi, J. Calcium Channel TRPV6 Promotes Breast Cancer Metastasis by NFATC2IP. Cancer Lett. 2021, 519, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-P.; Zhao, Y.-J.; Kong, X.-L. A Metalloproteinase of the Disintegrin and Metalloproteinases and the Thrombospondin Motifs 6 as a Novel Marker for Colon Cancer: Functional Experiments. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2020, 43, e20190266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, S.A.; Woods, S.; Singh, M.; Kimber, S.J.; Baldock, C. ADAMTS6 Cleaves the Large Latent TGFβ Complex and Increases the Mechanotension of Cells to Activate TGFβ. Matrix Biol. 2022, 114, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, S.A.; Mularczyk, E.J.; Singh, M.; Massam-Wu, T.; Kielty, C.M. ADAMTS-10 and -6 Differentially Regulate Cell-Cell Junctions and Focal Adhesions. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmagambetova, A.; Mustyatsa, V.; Saidova, A.; Vorobjev, I. Morphological and Cytoskeleton Changes in Cells after EMT. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.N.; Ahn, D.H.; Kang, N.; Yeo, C.D.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, T.-J.; Lee, S.H.; Park, M.S.; Yim, H.W.; et al. TGF-β Induced EMT and Stemness Characteristics Are Associated with Epigenetic Regulation in Lung Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tong, X.; Li, C.; Jin, E.; Su, Z.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, H. Quaking 5 Suppresses TGF-β-induced EMT and Cell Invasion in Lung Adenocarcinoma. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e52079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paterson, E.L.; Kazenwadel, J.; Bert, A.G.; Khew-Goodall, Y.; Ruszkiewicz, A.; Goodall, G.J. Down-Regulation of the miRNA-200 Family at the Invasive Front of Colorectal Cancers with Degraded Basement Membrane Indicates EMT Is Involved in Cancer Progression. Neoplasia 2013, 15, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, A.; Cortes, E.; Lachowski, D.; Oertle, P.; Matellan, C.; Thorpe, S.D.; Ghose, R.; Wang, H.; Lee, D.A.; Plodinec, M.; et al. GPER Activation Inhibits Cancer Cell Mechanotransduction and Basement Membrane Invasion via RhoA. Cancers 2020, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T.-T.-T.; Bach, D.-H.; Kim, D.; Hu, R.; Park, H.J.; Lee, S.K. Overexpression of AGR2 Is Associated With Drug Resistance in Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers. Anticancer Res. 2020, 40, 1855–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachat, C.; Bruyère, D.; Etcheverry, A.; Aubry, M.; Mosser, J.; Warda, W.; Herfs, M.; Hendrick, E.; Ferrand, C.; Borg, C.; et al. EZH2 and KDM6B Expressions Are Associated with Specific Epigenetic Signatures during EMT in Non Small Cell Lung Carcinomas. Cancers 2020, 12, 3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Li, Q.; Chen, S.; Huang, Y.; Ma, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, A.; Yuan, X.; et al. ADAMTS16 Drives Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Metastasis through a Feedback Loop upon TGF-Β1 Activation in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jiang, C.; Hu, N.; Hong, S. ADAMTS1 Induces Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Pathway in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Regulating TGF-β. Aging 2023, 15, 2097–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordian, E.; Welsh, E.A.; Gimbrone, N.; Siegel, E.M.; Shibata, D.; Creelan, B.C.; Cress, W.D.; Eschrich, S.A.; Haura, E.B.; Muñoz-Antonia, T. Transforming Growth Factor β-Induced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Signature Predicts Metastasis-Free Survival in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 810–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Daemen, A.; Hatzivassiliou, G.; Arnott, D.; Wilson, C.; Zhuang, G.; Gao, M.; Liu, P.; Boudreau, A.; Johnson, L.; et al. Metabolic and Transcriptional Profiling Reveals Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 4 as a Mediator of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Drug Resistance in Tumor Cells. Cancer Metab. 2014, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitai, H.; Ebi, H.; Tomida, S.; Floros, K.V.; Kotani, H.; Adachi, Y.; Oizumi, S.; Nishimura, M.; Faber, A.C.; Yano, S. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Defines Feedback Activation of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Signaling Induced by MEK Inhibition in KRAS-Mutant Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.-H.; Chen, S.-H.; Wu, H.-H.; Ho, C.-W.; Ko, M.-T.; Lin, C.-Y. cytoHubba: Identifying Hub Objects and Sub-Networks from Complex Interactome. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014, 8, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitoh, M. Transcriptional Regulation of EMT Transcription Factors in Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 97, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Qi, J.; Hou, Y.; Chang, J.; Ren, L. Upregulation of IL-11, an IL-6 Family Cytokine, Promotes Tumor Progression and Correlates with Poor Prognosis in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 45, 2213–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, S.; Hayakawa, Y.; Sakurai, H.; Saiki, I.; Yokoyama, S. Mesenchymal-Transitioned Cancer Cells Instigate the Invasion of Epithelial Cancer Cells through Secretion of WNT3 and WNT5B. Cancer Sci. 2014, 105, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Li, S.; Xiao, C.; Tian, H.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; He, J. CCL20 Promotes Lung Adenocarcinoma Progression by Driving Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4275–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, D.M.; Han, R.; Deng, Y.Y.S.H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, T.; Xu, Y. Low-Dose Radiation Promotes Invasion and Migration of A549 Cells by Activating the CXCL1/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 3619–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Chen, F.; Song, Z.; Cao, C. MicroRNA-148a-3p Directly Targets SERPINE1 to Suppress EMT-Mediated Colon Adenocarcinoma Progression. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 6349–6362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Xu, D.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gong, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Xing, B. THBS1 Facilitates Colorectal Liver Metastasis through Enhancing Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2020, 22, 1730–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Fu, X.; Li, R. CNN1 Regulates the DKK1/Wnt/Β-catenin/C-myc Signaling Pathway by Activating TIMP2 to Inhibit the Invasion, Migration and EMT of Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschkowski, D.; Vierbuchen, T.; Heine, H.; Behrends, J.; Reiling, N.; Reck, M.; Rabe, K.F.; Kugler, C.; Ammerpohl, O.; Drömann, D.; et al. SMAD2 Linker Phosphorylation Impacts Overall Survival, Proliferation, TGFβ1-Dependent Gene Expression and Pluripotency-Related Proteins in NSCLC. Br. J. Cancer 2025, 133, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J.; Pirooznia, M.; Li, Y.; Xiong, J. The Short-Chain Fatty Acid Acetate Modulates Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Mol. Biol. Cell 2022, 33, br13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, D.; Zhao, W.; Vallega, K.A.; Sun, S.-Y. Managing Acquired Resistance to Third-Generation EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Through Co-Targeting MEK/ERK Signaling. Lung Cancer Targets Ther. 2021, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, F.A.; Hsu, P.D.; Wright, J.; Agarwala, V.; Scott, D.A.; Zhang, F. Genome Engineering Using the CRISPR-Cas9 System. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 2281–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykke-Andersen, S.; Jensen, T.H. Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay: An Intricate Machinery That Shapes Transcriptomes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguiano, M.; Morales, X.; Castilla, C.; Pena, A.R.; Ederra, C.; Martínez, M.; Ariz, M.; Esparza, M.; Amaveda, H.; Mora, M.; et al. The Use of Mixed Collagen-Matrigel Matrices of Increasing Complexity Recapitulates the Biphasic Role of Cell Adhesion in Cancer Cell Migration: ECM Sensing, Remodeling and Forces at the Leading Edge of Cancer Invasion. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0220019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Shu-Ling, W.; Jing-Bo, H.; Ying, Z.; Rong, H.; Xiang-Qun, L.; Wen-Jie, C.; Lin-Fu, Z. MiR-451a Attenuates Doxorubicin Resistance in Lung Cancer via Suppressing Epithelialmesenchymal Transition (EMT) through Targeting c-Myc. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 125, 109962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T.; Saitoh, M.; Miyazawa, K. TGF-β Enhances Doxorubicin Resistance and Anchorage-Independent Growth in Cancer Cells by Inducing ALDH1A1 Expression. Cancer Sci. 2025, 116, 2176–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, A.R.; Mackay, A.R. Gelatinase B/MMP-9 in Tumour Pathogenesis and Progression. Cancers 2014, 6, 240–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoari, A.; Ashja Ardalan, A.; Dimesa, A.M.; Coban, M.A. Targeting Invasion: The Role of MMP-2 and MMP-9 Inhibition in Colorectal Cancer Therapy. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili-Tanha, G.; Radisky, E.S.; Radisky, D.C.; Shoari, A. Matrix Metalloproteinase-Driven Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition: Implications in Health and Disease. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashja Ardalan, A.; Khalili-Tanha, G.; Shoari, A. Shaping the Landscape of Lung Cancer: The Role and Therapeutic Potential of Matrix Metalloproteinases. Int. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 4, 661–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-C.; Chang, C.-Y.; Huang, Y.-C.; Wu, K.-L.; Chiang, H.-H.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Liu, L.-X.; Hung, J.-Y.; Hsu, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.-Y.; et al. Downregulated ADAMTS1 Incorporating A2M Contributes to Tumorigenesis and Alters Tumor Immune Microenvironment in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Biology 2022, 11, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-C.; Chang, C.-Y.; Wu, K.-L.; Chiang, H.-H.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Liu, L.-X.; Huang, Y.-C.; Hung, J.-Y.; Hsu, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.-Y.; et al. The Therapeutic Potential of ADAMTS8 in Lung Adenocarcinoma without Targetable Therapy. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Mu, J.; Guo, S.; Ye, L.; Li, D.; Peng, W.; He, X.; Xiang, T. Inactivation of ADAMTS18 by Aberrant Promoter Hypermethylation Contribute to Lung Cancer Progression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 6965–6975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Yang, W.; Ge, J.; Xiao, X.; Wu, K.; She, K.; Zhou, Y.; Kong, Y.; Wu, L.; Luo, S.; et al. ADAMTS4 Exacerbates Lung Cancer Progression via Regulating C-Myc Protein Stability and Activating MAPK Signaling Pathway. Biol. Direct 2024, 19, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Chen, J.; Feng, J.; Liu, Y.; Xue, Q.; Mao, G.; Gai, L.; Lu, X.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, J.; et al. Overexpression of ADAMTS5 Can Regulate the Migration and Invasion of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 8681–8689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuffaro, D.; Ciccone, L.; Rossello, A.; Nuti, E.; Santamaria, S. Targeting Aggrecanases for Osteoarthritis Therapy: From Zinc Chelation to Exosite Inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 13505–13532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Q. Full-Length ADAMTS-1 and the ADAMTS-1 Fragments Display pro- and Antimetastatic Activity, Respectively. Oncogene 2006, 25, 2452–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawata, M.; Koinuma, D.; Ogami, T.; Umezawa, K.; Iwata, C.; Watabe, T.; Miyazono, K. TGF-β-Induced Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of A549 Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells Is Enhanced by pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Derived from RAW 264.7 Macrophage Cells. J. Biochem. 2012, 151, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borthwick, L.A.; Gardner, A.; De Soyza, A.; Mann, D.A.; Fisher, A.J. Transforming Growth Factor-Β1 (TGF-Β1) Driven Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) Is Accentuated by Tumour Necrosis Factor α (TNFα) via Crosstalk Between the SMAD and NF-κB Pathways. Cancer Microenviron. 2012, 5, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Percevault, F.; Ryder, K.; Sani, E.; Le Cun, J.-C.; Zhadobov, M.; Sauleau, R.; Le Dréan, Y.; Habauzit, D. Effects of Radiofrequency Radiation on Gene Expression: A Study of Gene Expressions of Human Keratinocytes from Different Origins. Bioelectromagnetics 2020, 41, 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevitt, D.J.; Mohamed, J.; Catterall, J.B.; Li, Z.; Arris, C.E.; Hiscott, P.; Sheridan, C.; Langton, K.P.; Barker, M.D.; Clarke, M.P.; et al. Expression of ADAMTS Metalloproteinases in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium Derived Cell Line ARPE-19: Transcriptional Regulation by TNFα. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gene Struct. Expr. 2003, 1626, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gou, Q.; Xie, K.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, H. ADAMTS6 Suppresses Tumor Progression via the ERK Signaling Pathway and Serves as a Prognostic Marker in Human Breast Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 61273–61283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lei, Y.; Chu, Y.; Yu, X.; Tong, Q.; Zhu, T.; Yu, H.; Fang, S.; Li, G.; et al. NNMT Contributes to High Metastasis of Triple Negative Breast Cancer by Enhancing PP2A/MEK/ERK/c-Jun/ABCA1 Pathway Mediated Membrane Fluidity. Cancer Lett. 2022, 547, 215884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulanovskaya, O.A.; Zuhl, A.M.; Cravatt, B.F. NNMT Promotes Epigenetic Remodeling in Cancer by Creating a Metabolic Methylation Sink. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedler, A.; Bley, N.; Glaß, M.; Müller, S.; Rausch, A.; Lederer, M.; Urbainski, J.; Schian, L.; Obika, K.-B.; Simon, T.; et al. RAVER1 Hinders Lethal EMT and Modulates miR/RISC Activity by the Control of Alternative Splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 3971–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sławińska-Brych, A.; Mizerska-Kowalska, M.; Król, S.K.; Stepulak, A.; Zdzisińska, B. Xanthohumol Impairs the PMA-Driven Invasive Behaviour of Lung Cancer Cell Line A549 and Exerts Anti-EMT Action. Cells 2021, 10, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abera, M.B.; Kazanietz, M.G. Protein Kinase Cα Mediates Erlotinib Resistance in Lung Cancer Cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015, 87, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, J.; Zang, G.; Song, S.; Sun, Z.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, G.; Gui, N.; et al. Pin1/YAP Pathway Mediates Matrix Stiffness-Induced Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition Driving Cervical Cancer Metastasis via a Non-Hippo Mechanism. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2023, 8, e10375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurppa, K.J.; Liu, Y.; To, C.; Zhang, T.; Fan, M.; Vajdi, A.; Knelson, E.H.; Xie, Y.; Lim, K.; Cejas, P.; et al. Treatment-Induced Tumor Dormancy through YAP-Mediated Transcriptional Reprogramming of the Apoptotic Pathway. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, H.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Tong, X. CRTC2 Activates the Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition of Diabetic Kidney Disease through the CREB-Smad2/3 Pathway. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.; Tong, S.; Gao, L. Identification of MDK as a Hypoxia- and Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition-Related Gene Biomarker of Glioblastoma Based on a Novel Risk Model and In Vitro Experiments. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Ma, L.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Ji, Z. POLR3G Promotes EMT via PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway in Bladder Cancer. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e23260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Guan, J.-L. Compensatory Function of Pyk2 Protein in the Promotion of Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK)-Null Mammary Cancer Stem Cell Tumorigenicity and Metastatic Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 18573–18582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujioka, M.; Miyazawa, K.; Ohmuraya, M.; Nibe, Y.; Shirokawa, T.; Hayasaka, H.; Mizushima, T.; Fukuma, T.; Shimizu, S. Identification of a Novel Type of Focal Adhesion Remodelling via FAK/FRNK Replacement, and Its Contribution to Cancer Progression. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerova, L.; Ondrouskova, E.; Vojtesek, B.; Hrstka, R. Suppression of AGR2 in a TGF-β-Induced Smad Regulatory Pathway Mediates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Ni, W.; Xuan, Y. ADAMTS-6 Is a Predictor of Poor Prognosis in Patients with Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2018, 104, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, N.; Wu, W.; Li, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, X. Molecular Mechanism of CD163+ Tumor-Associated Macrophage (TAM)-Derived Exosome-Induced Cisplatin Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Ascites. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmajda-Krygier, D.; Nocoń, Z.; Pietrzak, J.; Krygier, A.; Balcerczak, E. Assessment of Methylation in Selected ADAMTS Family Genes in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, J.; Świechowski, R.; Wosiak, A.; Wcisło, S.; Balcerczak, E. ADAMTS Gene-Derived circRNA Molecules in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Expression Profiling, Clinical Correlations and Survival Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Cho, M.; Wang, X. OncoDB: An Interactive Online Database for Analysis of Gene Expression and Viral Infection in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D1334–D1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, D.S.; Karthikeyan, S.K.; Korla, P.K.; Patel, H.; Shovon, A.R.; Athar, M.; Netto, G.J.; Qin, Z.S.; Kumar, S.; Manne, U.; et al. UALCAN: An Update to the Integrated Cancer Data Analysis Platform. Neoplasia 2022, 25, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.P.; Vanderhyden, B.C. Context Specificity of the EMT Transcriptional Response. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Park, J.; Kim, J.-S. Cas-OFFinder: A Fast and Versatile Algorithm That Searches for Potential off-Target Sites of Cas9 RNA-Guided Endonucleases. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1473–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, R.; Meister, M.; Muley, T.; Thomas, M.; Sültmann, H.; Warth, A.; Winter, H.; Herth, F.J.F.; Schneider, M.A. Pathways Regulating the Expression of the Immunomodulatory Protein Glycodelin in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, O.-S.; Kwon, E.-J.; Kong, H.-J.; Choi, J.-Y.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, E.-W.; Kim, W.; Lee, H.; Cha, H.-J. Systematic Identification of a Nuclear Receptor-Enriched Predictive Signature for Erastin-Induced Ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, G.Y.; Hong, S.K.; Park, J.R.; Kwon, O.S.; Kim, K.T.; Koo, J.H.; Oh, E.; Cha, H.J. Chronic TGFβ Stimulation Promotes the Metastatic Potential of Lung Cancer Cells by Snail Protein Stabilization through Integrin Β3-Akt-GSK3β Signaling. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 25366–25376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvornikov, D.; Schneider, M.A.; Ohse, S.; Szczygieł, M.; Titkova, I.; Rosenblatt, M.; Muley, T.; Warth, A.; Herth, F.J.; Dienemann, H.; et al. Expression Ratio of the TGFβ-Inducible Gene MYO10 Is Prognostic for Overall Survival of Squamous Cell Lung Cancer Patients and Predicts Chemotherapy Response. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Li, X.; Kalita, M.; Widen, S.G.; Yang, J.; Bhavnani, S.K.; Dang, B.; Kudlicki, A.; Sinha, M.; Kong, F.; et al. Analysis of the TGFβ-Induced Program in Primary Airway Epithelial Cells Shows Essential Role of NF-κB/RelA Signaling Network in Type II Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladilin, E.; Ohse, S.; Boerries, M.; Busch, H.; Xu, C.; Schneider, M.; Meister, M.; Eils, R. TGFβ-Induced Cytoskeletal Remodeling Mediates Elevation of Cell Stiffness and Invasiveness in NSCLC. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Ong, S.L.; Tran, L.M.; Jing, Z.; Liu, B.; Park, S.J.; Huang, Z.L.; Walser, T.C.; Heinrich, E.L.; Lee, G.; et al. Chronic IL-1β-Induced Inflammation Regulates Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Memory Phenotypes via Epigenetic Modifications in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, K.E.; Hinz, T.K.; Kleczko, E.; Singleton, K.R.; Marek, L.A.; Helfrich, B.A.; Cummings, C.T.; Graham, D.K.; Astling, D.; Tan, A.-C.; et al. A Mechanism of Resistance to Gefitinib Mediated by Cellular Reprogramming and the Acquisition of an FGF2-FGFR1 Autocrine Growth Loop. Oncogenesis 2013, 2, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, L.; Jia, W.; Gong, Q.; Cui, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Fu, C.; Li, H.; Wei, J.; Wang, R.; et al. Targeting GFPT2 to Reinvigorate Immunotherapy in EGFR-Mutated NSCLC. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.03.01.582888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Mayo, M.W.; Xiao, A.; Hall, E.H.; Amin, E.B.; Kadota, K.; Adusumilli, P.S.; Jones, D.R. Loss of BRMS1 Promotes a Mesenchymal Phenotype Through NF-κB-Dependent Regulation of Twist1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2015, 35, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiozaki, A.; Bai, X.; Shen-Tu, G.; Moodley, S.; Takeshita, H.; Fung, S.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Keshavjee, S.; Liu, M. Claudin 1 Mediates TNFα-Induced Gene Expression and Cell Migration in Human Lung Carcinoma Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Odarenko, K.V.; Matveeva, A.M.; Stepanov, G.A.; Zenkova, M.A.; Markov, A.V. Deciphering the Role of ADAMTS6 in the Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition of Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411850

Odarenko KV, Matveeva AM, Stepanov GA, Zenkova MA, Markov AV. Deciphering the Role of ADAMTS6 in the Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition of Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411850

Chicago/Turabian StyleOdarenko, Kirill V., Anastasiya M. Matveeva, Grigory A. Stepanov, Marina A. Zenkova, and Andrey V. Markov. 2025. "Deciphering the Role of ADAMTS6 in the Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition of Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411850

APA StyleOdarenko, K. V., Matveeva, A. M., Stepanov, G. A., Zenkova, M. A., & Markov, A. V. (2025). Deciphering the Role of ADAMTS6 in the Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition of Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11850. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411850