Alginate-Based Microparticles Containing Albumin and Doxorubicin: Nanoarchitectonics and Characterization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

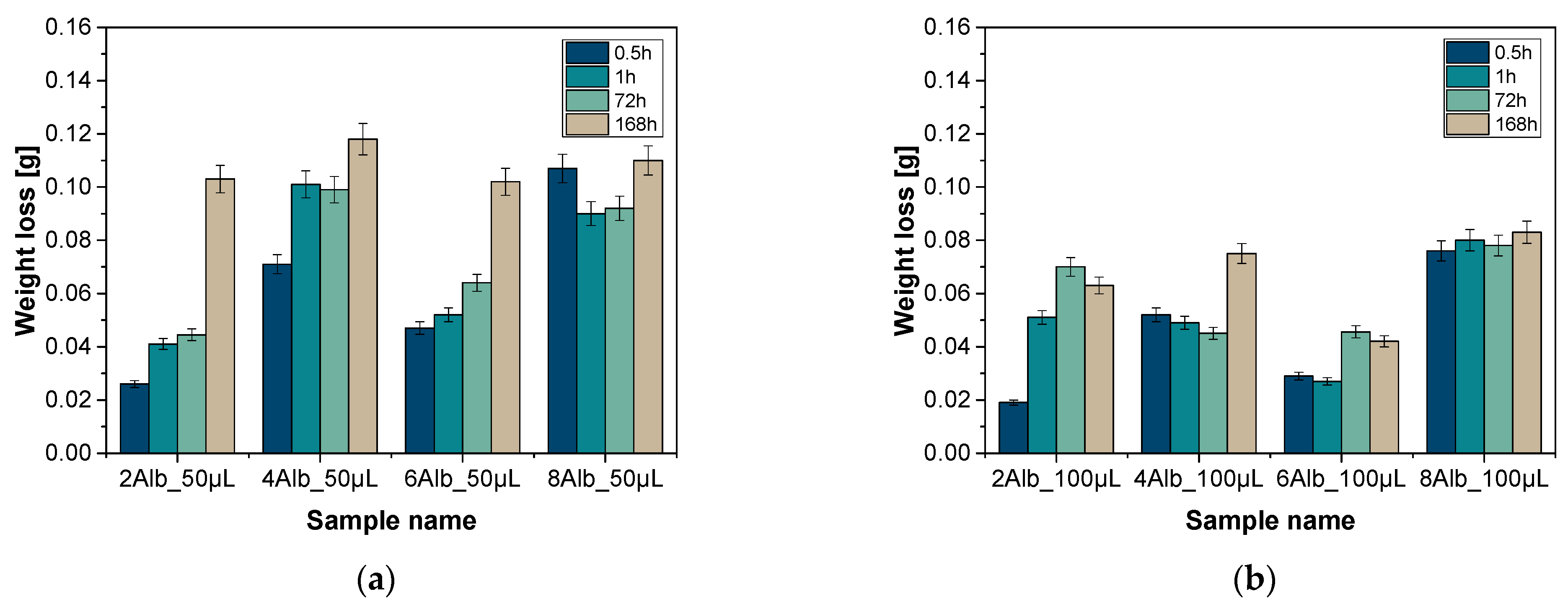

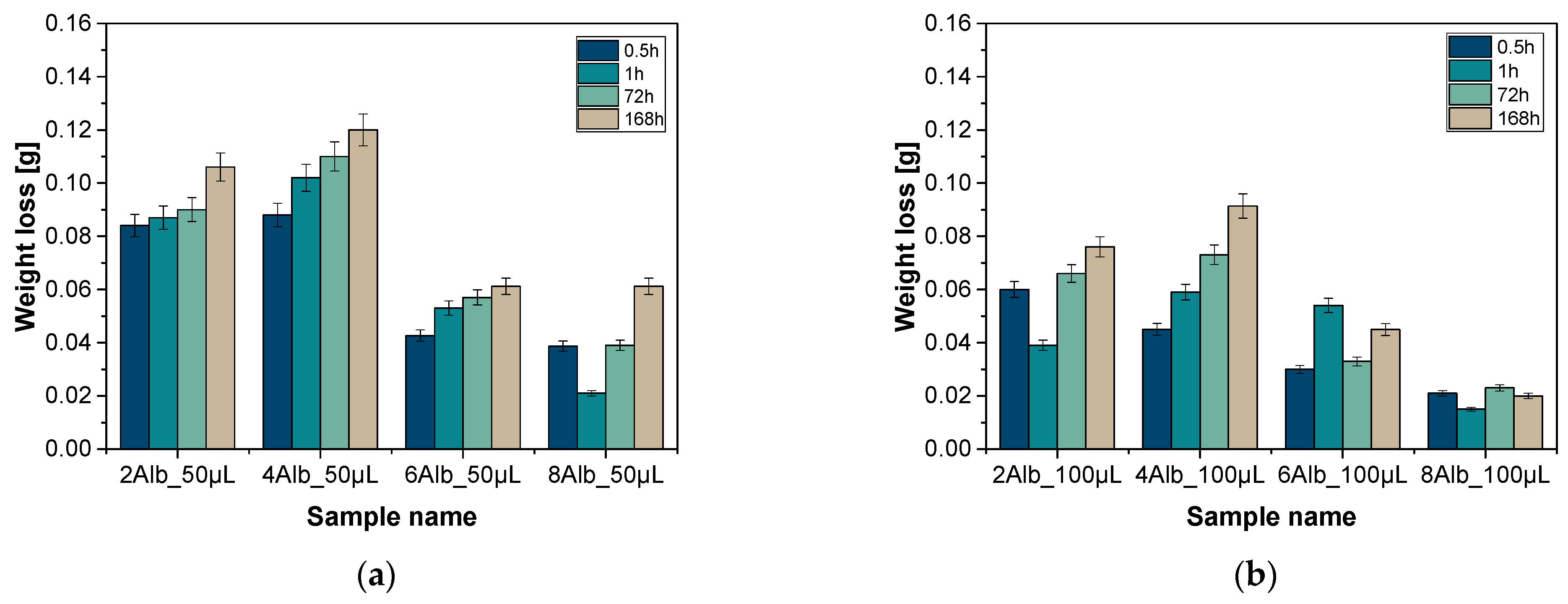

2.1. Analysis of Weight Loss

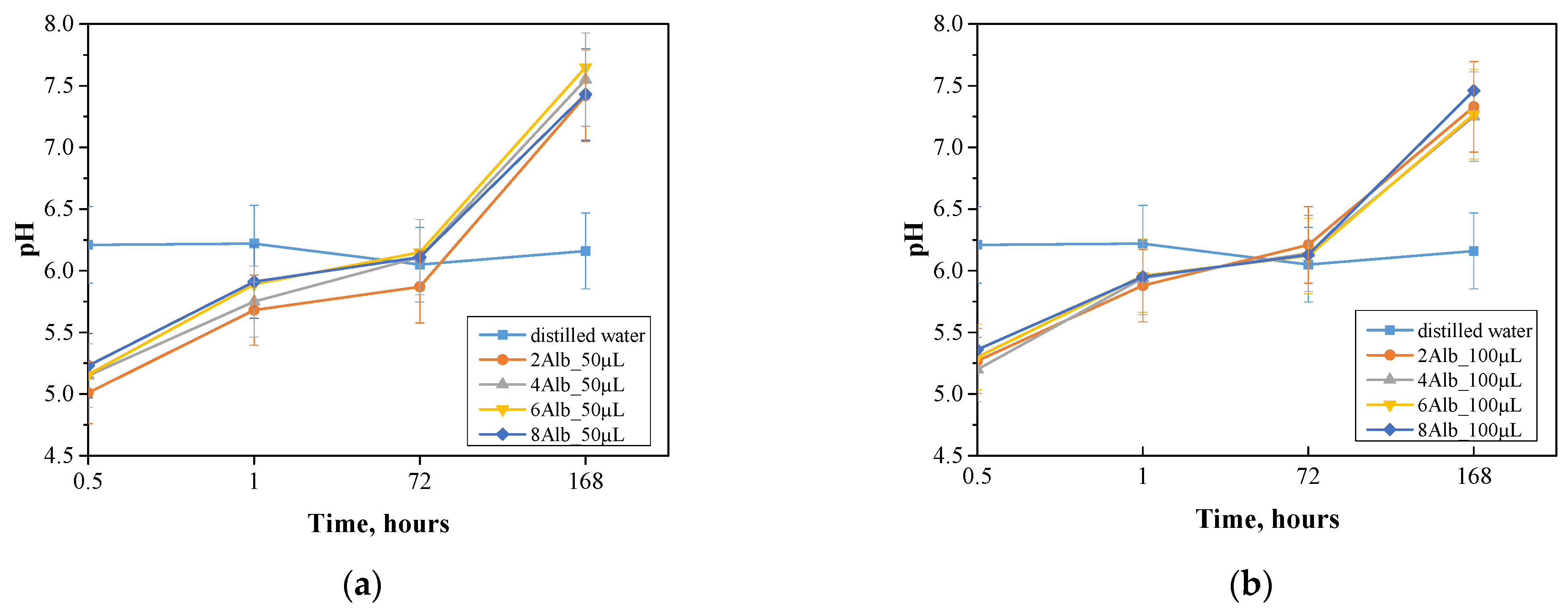

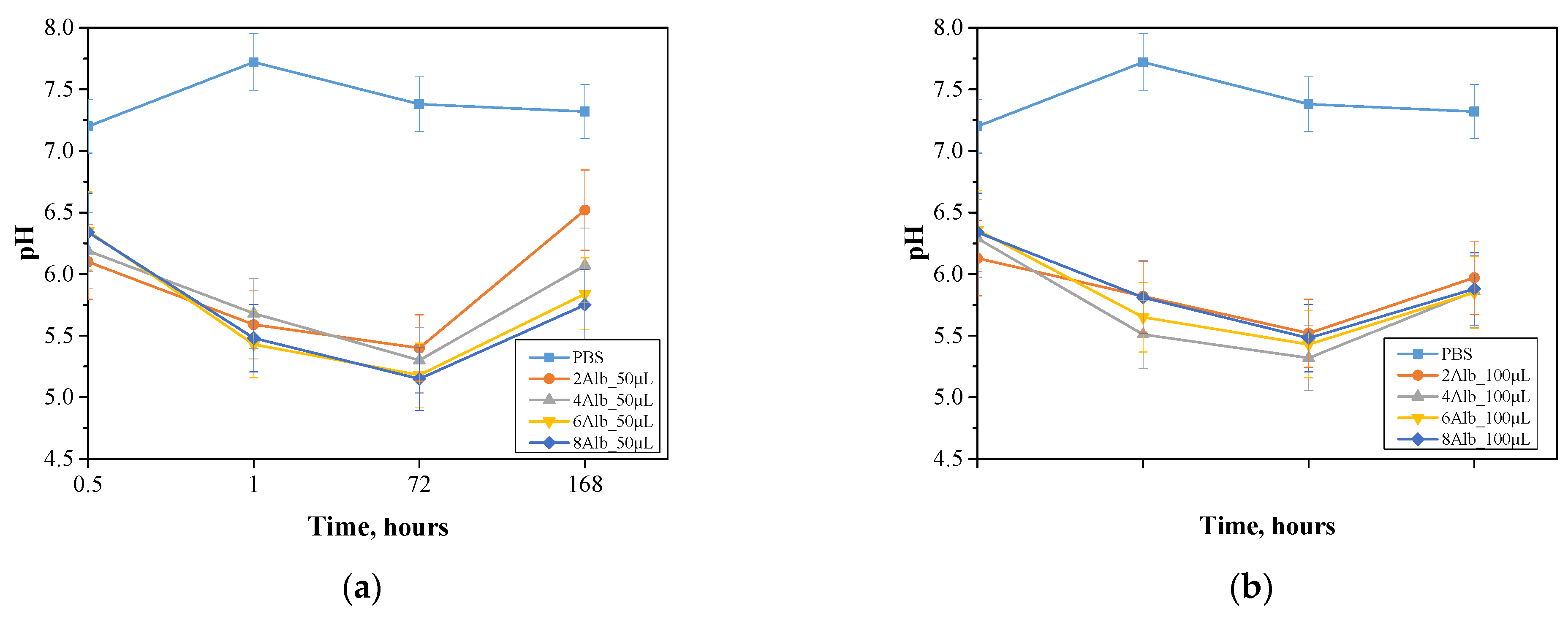

2.2. Incubation in Simulated Body Fluids

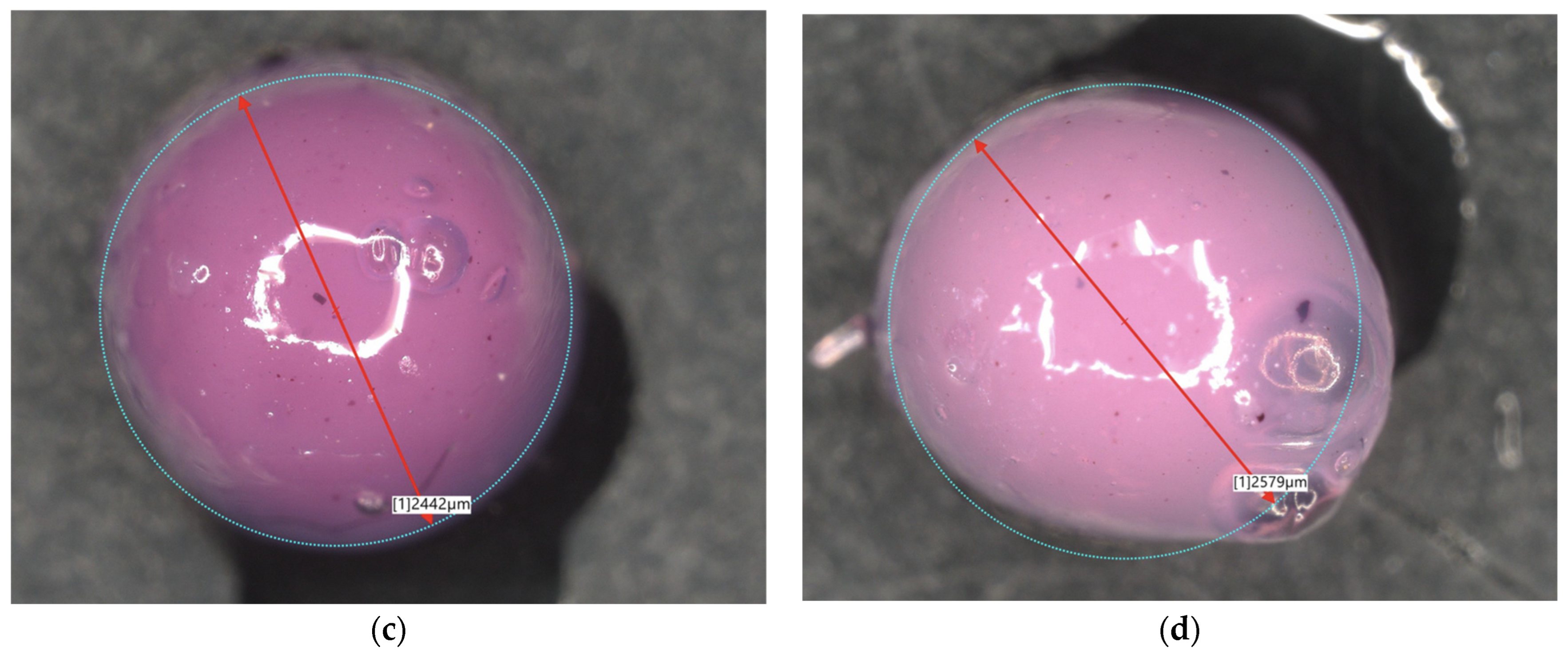

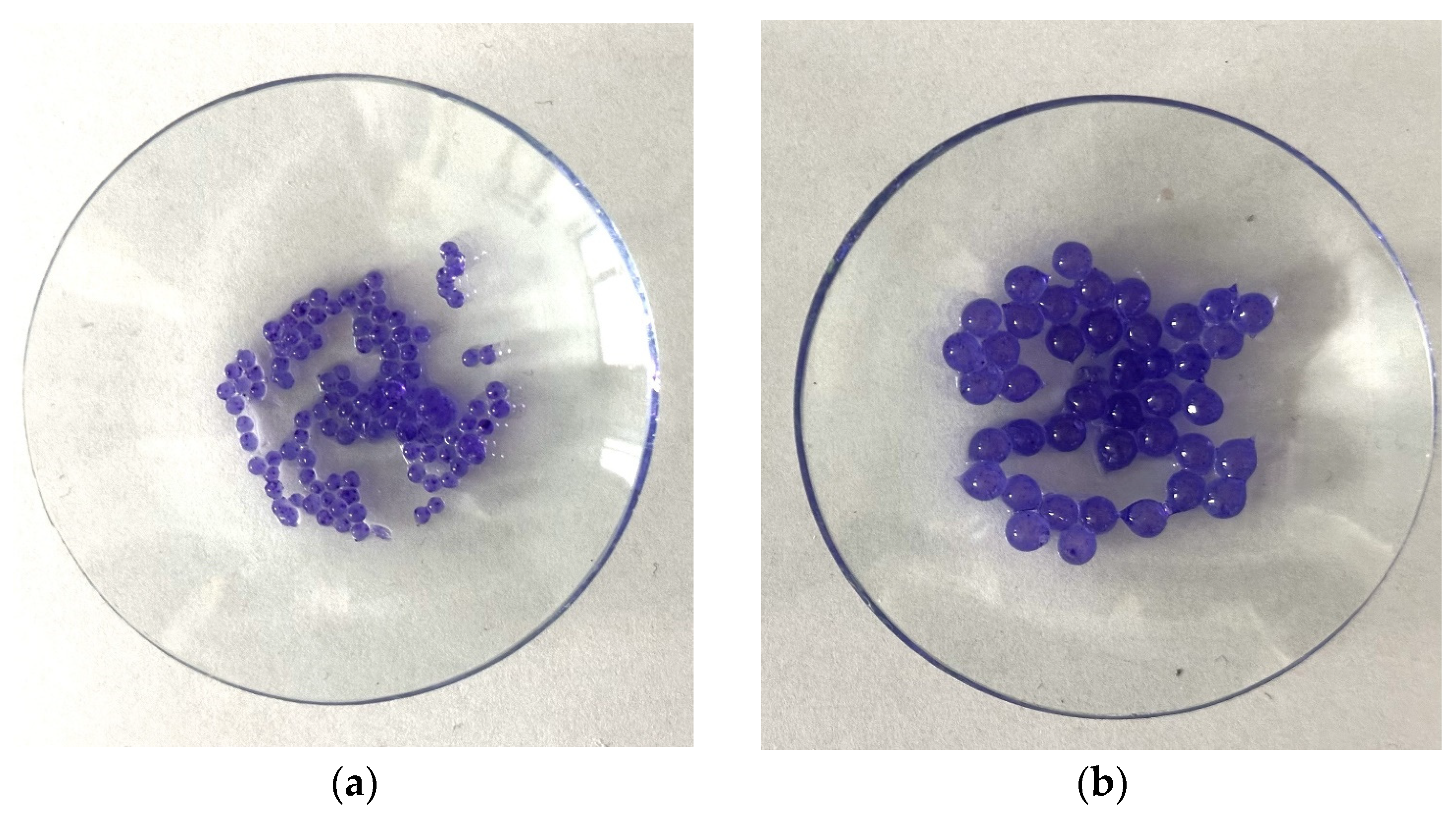

2.3. Microscopic Observations

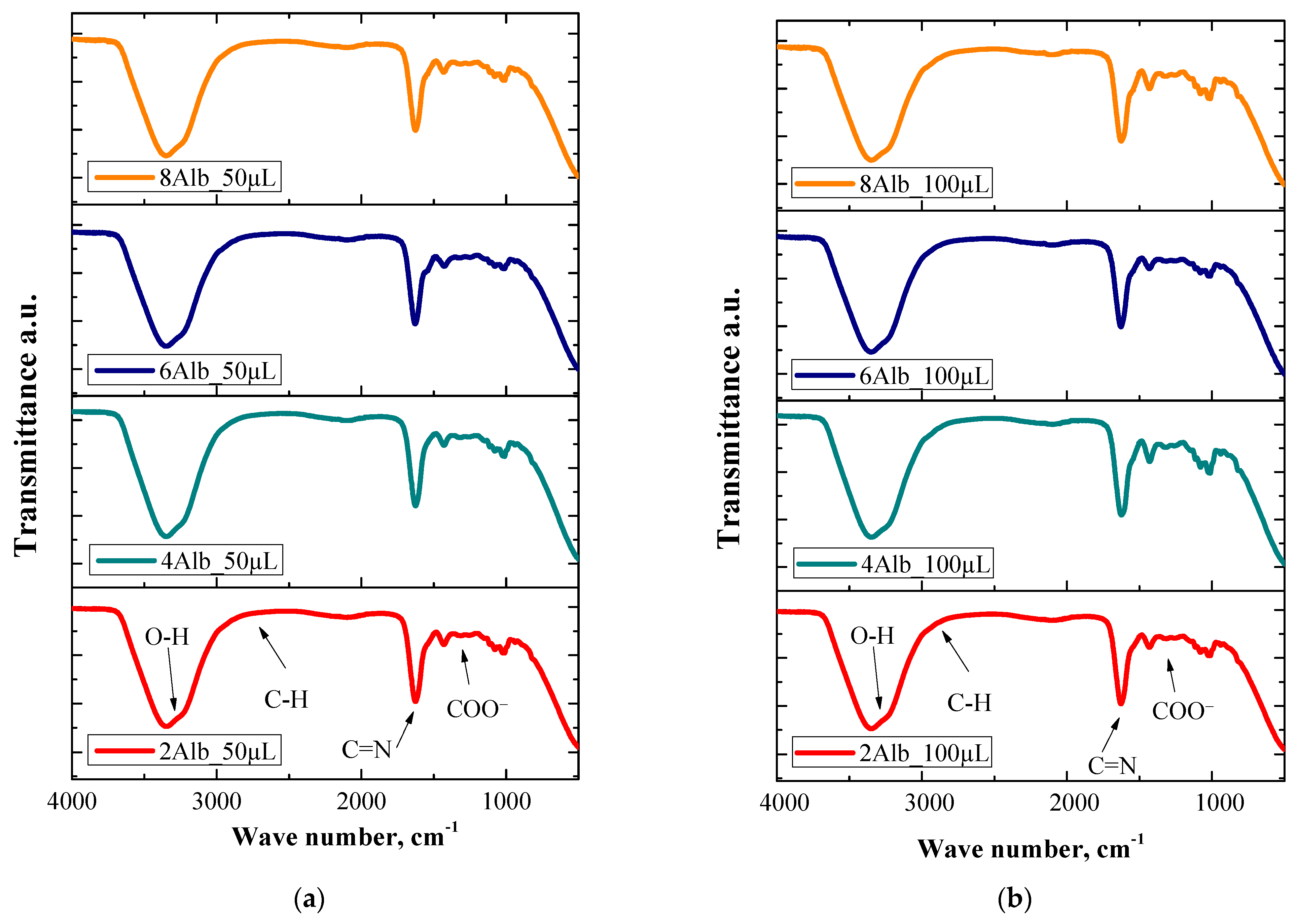

2.4. Physicochemical Analysis

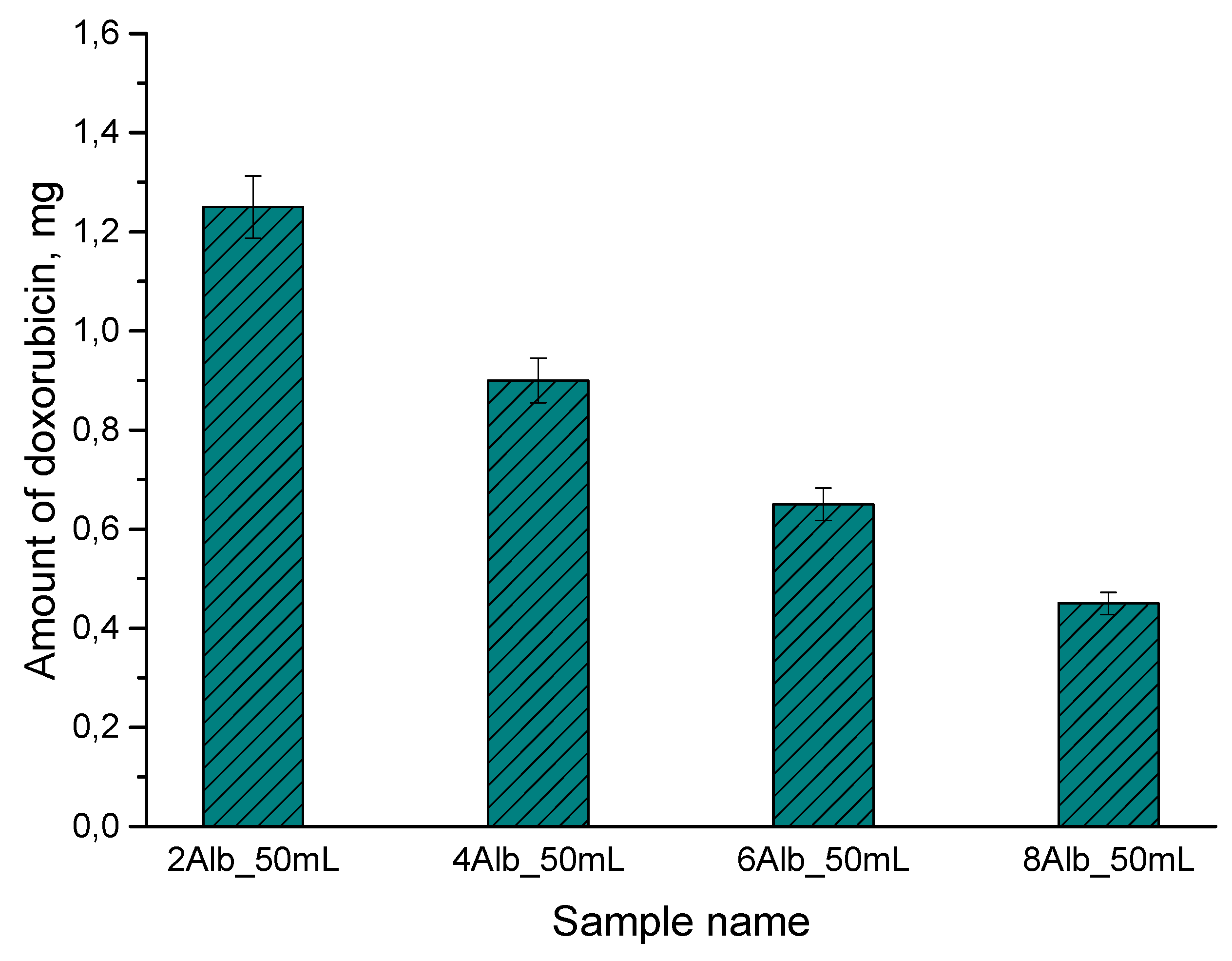

2.5. Doxorubicin Release Study

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

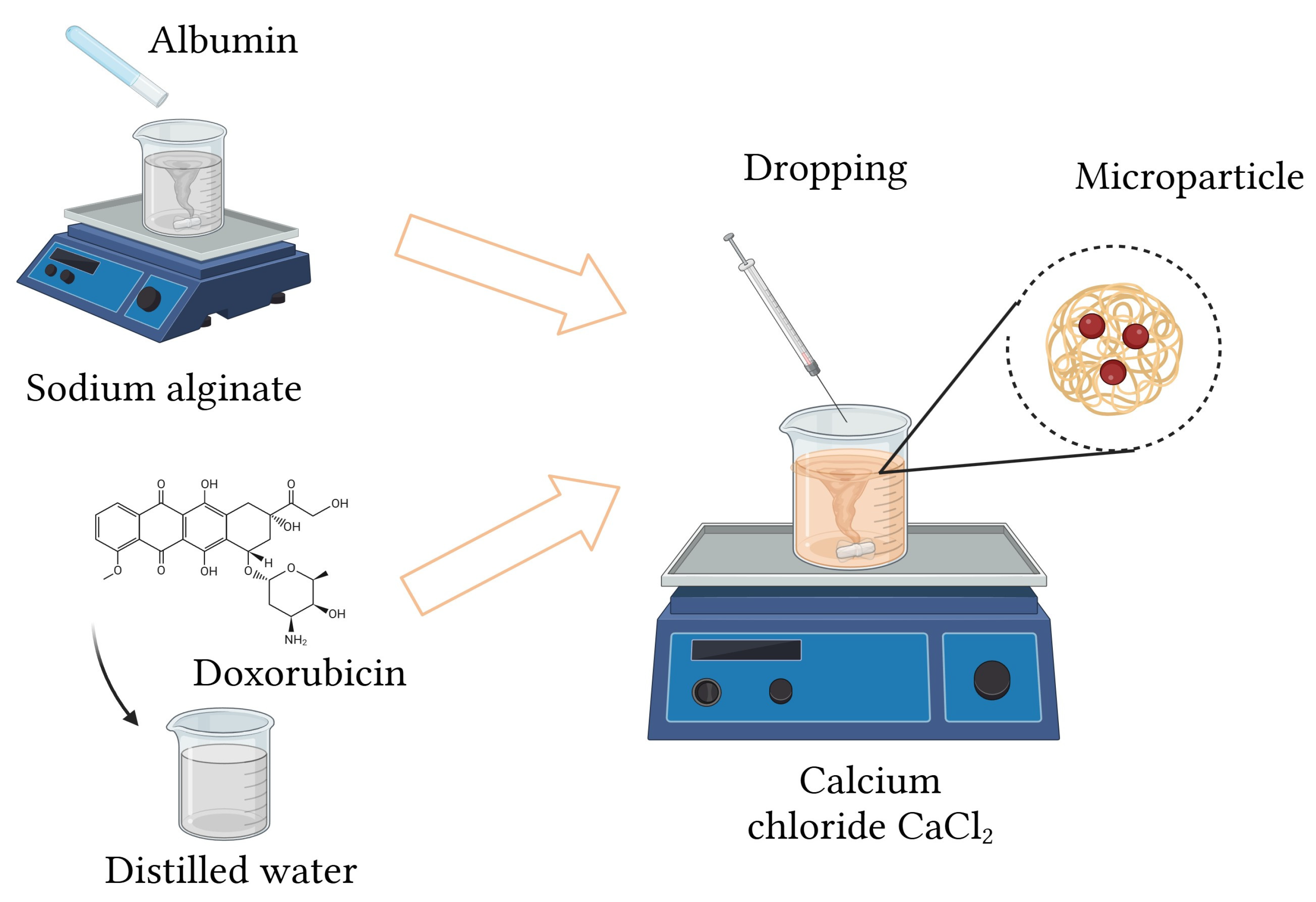

3.2. Synthesis of Protein Carriers

3.3. Analysis of Weight Loss

- m—mass of swollen protein capsule, g;

- m0—mass of dry protein capsule, g.

3.4. Incubation in Simulated Body Fluids

3.5. Microscopic Observations

3.6. FT-IR Spectroscopy

3.7. Doxorubicin Release Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schneider, S.; Feilen, P.; Cramer, H.; Hillgärtner, M.; Brunnenmeier, F.; Zimmermann, H.; Weber, M.M.; Zimmermann, U. Beneficial Effects of Human Serum Albumin on Stability and Functionality of Alginate Microcapsules Fabricated in Different Ways. J. Microencapsul. 2003, 20, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.U.D.; Ali, M.; Mehdi, S.; Masoodi, M.H.; Zargar, M.I.; Shakeel, F. A Review on Chitosan and Alginate-Based Microcapsules: Mechanism and Applications in Drug Delivery Systems. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 248, 125875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, S.; Chen, W.; Zheng, X.; Ma, L. Preparation of PH-Sensitive Alginate-Based Hydrogel by Microfluidic Technology for Intestinal Targeting Drug Delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antezana, P.E.; Municoy, S.; Silva Sofrás, F.M.; Bellino, M.G.; Evelson, P.; Desimone, M.F. Alginate-Based Microencapsulation as a Strategy to Improve the Therapeutic Potential of Cannabidiolic Acid. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 669, 125076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.-H.; Wu, Q.-X.; Ding, Z.-F. Microencapsulation of Functional Ovalbumin and Bovine Serum Albumin with Polylysine-Alginate Complex for Sustained Protein Vehicle’s Development. Food Chem. 2022, 368, 130902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzoghby, A.O.; Samy, W.M.; Elgindy, N.A. Albumin-Based Nanoparticles as Potential Controlled Release Drug Delivery Systems. J. Control. Release 2012, 157, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, N.; Song, K.; Ji, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, L.; Lee, R.J.; Teng, L. Albumin Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 6945–6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandy, T.; Mooradian, D.L.; Rao, G.H. Evaluation of Modified Alginate-Chitosan-Polyethylene Glycol Microcapsules for Cell Encapsulation. Artif. Organs 1999, 23, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Belhaj, M.; DiPette, D.J.; Potts, J.D. A Novel Alginate-Based Delivery System for the Prevention and Treatment of Pressure-Overload Induced Heart Failure. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 602952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, R.; Xie, H.; Zheng, H.; Ren, Y.; Gao, M.; Guo, X.; Song, Y.; Yu, W.; Liu, X.; Ma, X. Alginate-Based Microcapsules with Galactosylated Chitosan Internal for Primary Hepatocyte Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 93, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, S.R.; Kovacevic, B.; Walker, D.; Ionescu, C.M.; Shah, U.; Stojanovic, G.; Kojic, S.; Mooranian, A.; Al-Salami, H. Alginate-Based Drug Oral Targeting Using Bio-Micro/Nano Encapsulation Technologies. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2020, 17, 1361–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zheng, H.; Tang, Q.; Dong, Y.; Qu, F.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.; Meng, T. Monodisperse Alginate Microcapsules with Spatially Confined Bioactive Molecules via Microfluid-Generated W/W/O Emulsions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 37313–37321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanucci, P.; Cari, L.; Basta, G.; Pescara, T.; Riccardi, C.; Nocentini, G.; Calafiore, R. Engineered Alginate Microcapsules for Molecular Therapy Through Biologic Secreting Cells. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2019, 25, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, G.; Neumann, M.; Meunier, C.F.; Fattaccioli, A.; Michiels, C.; Arnould, T.; Wang, L.; Su, B.-L. Hybrid Alginate@TiO(2) Porous Microcapsules as a Reservoir of Animal Cells for Cell Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 37865–37877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, H. Development and Characterization of Starch-sodium Alginate-Montmorillonite Biodegradable Antibacterial Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Cui, Z.; Lv, J.; Yang, F.; Huo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ju, J. The Combination of Sodium Alginate and Chlorogenic Acid Enhances the Therapeutic Effect on Ulcerative Colitis by the Regulation of Inflammation and the Intestinal Flora. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 10710–10723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.Y.; Mooney, D.J. Alginate: Properties and Biomedical Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, S.; Li, Y.; Niu, C.; Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, J.; Wang, X. Silk Fibroin/Sodium Alginate Composite Porous Materials with Controllable Degradation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 1314–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Shang, Z.; Liu, H.; Yuan, Z.-X. Alginate-Based Platforms for Cancer-Targeted Drug Delivery. Biomed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1487259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, F.; Li, J.; Qin, Z.; Yang, B.; Zhang, E.; Dong, D.; Wang, J.; Wen, Y.; Tian, L.; Yao, F. Engineering Pectin-Based Hollow Nanocapsules for Delivery of Anticancer Drug. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 177, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, H.-L.; Wang, L.-P. PH-Sensitive, Polymer Functionalized, Nonporous Silica Nanoparticles for Quercetin Controlled Release. Polymers 2019, 11, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Nai, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ma, S.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, M.; et al. A Novel Preparative Method for Nanoparticle Albumin-Bound Paclitaxel with High Drug Loading and Its Evaluation Both in Vitro and in Vivo. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Wang, M.; Wu, Z.; Cui, S.W.; Wang, H.; Wang, B. Stability and Bioaccessibility Improvement of Capsorubin Using Bovine Serum Albumin-Dextran-Gallic Acid and Sodium Alginate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 1362–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roacho-Pérez, J.A.; Rodríguez-Aguillón, K.O.; Gallardo-Blanco, H.L.; Velazco-Campos, M.R.; Sosa-Cruz, K.V.; García-Casillas, P.E.; Rojas-Patlán, L.; Sánchez-Domínguez, M.; Rivas-Estilla, A.M.; Gómez-Flores, V.; et al. A Full Set of In Vitro Assays in Chitosan/Tween 80 Microspheres Loaded with Magnetite Nanoparticles. Polymers 2021, 13, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, G.; Walke, S.; Dhavale, D.; Gade, W.; Doshi, J.; Kumar, R.; Ravetkar, S.; Doshi, P. Tartrate/Tripolyphosphate as Co-Crosslinker for Water Soluble Chitosan Used in Protein Antigens Encapsulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 91, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steichen, S.; O’Connor, C.; Peppas, N.A. Development of a P((MAA-Co-NVP)-g-EG) Hydrogel Platform for Oral Protein Delivery: Effects of Hydrogel Composition on Environmental Response and Protein Partitioning. Macromol. Biosci. 2017, 17, 1600266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name | Diameter [µm] | Sample Name | Diameter [µm] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2Alb_50mL | 1239 | 2Alb_100mL | 2168 |

| 4Alb_50mL | 1262 | 4Alb_100mL | 2683 |

| 6Alb_50mL | 1334 | 6Alb_100mL | 2442 |

| 8Alb_50mL | 1433 | 8Alb_100mL | 2579 |

| Sample Number | Sodium Alginate [mL] | Albumin [mg/mL] | Doxorubicin [mg] | Sample Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | 2 | 2.5 | 2Alb_50mL/2Alb_100mL |

| 2 | 4 | 4Alb_50mL/4Alb_100mL | ||

| 3 | 6 | 6Alb_50mL/6Alb_100mL | ||

| 4 | 8 | 8Alb_50mL/8Alb_100mL |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kędzierska, M.; Sala, K.; Wanat, D.; Wroniak, D.; Bańkosz, M.; Potemski, P.; Tyliszczak, B. Alginate-Based Microparticles Containing Albumin and Doxorubicin: Nanoarchitectonics and Characterization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411800

Kędzierska M, Sala K, Wanat D, Wroniak D, Bańkosz M, Potemski P, Tyliszczak B. Alginate-Based Microparticles Containing Albumin and Doxorubicin: Nanoarchitectonics and Characterization. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411800

Chicago/Turabian StyleKędzierska, Magdalena, Katarzyna Sala, Dominika Wanat, Dominika Wroniak, Magdalena Bańkosz, Piotr Potemski, and Bożena Tyliszczak. 2025. "Alginate-Based Microparticles Containing Albumin and Doxorubicin: Nanoarchitectonics and Characterization" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411800

APA StyleKędzierska, M., Sala, K., Wanat, D., Wroniak, D., Bańkosz, M., Potemski, P., & Tyliszczak, B. (2025). Alginate-Based Microparticles Containing Albumin and Doxorubicin: Nanoarchitectonics and Characterization. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411800