Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Health and Disease: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

Scope and Literature Selection

2. Molecular Mechanisms and Pathophysiological Roles of EndMT

2.1. Transforming Growth Factor-β

2.2. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in EndMT

2.3. Transcriptional Regulation of EndMT

2.4. Epigenetics

2.4.1. DNA Methylation

2.4.2. Histone Modification

2.4.3. MicroRNA

2.5. Plasticity and Reversibility of EndMT

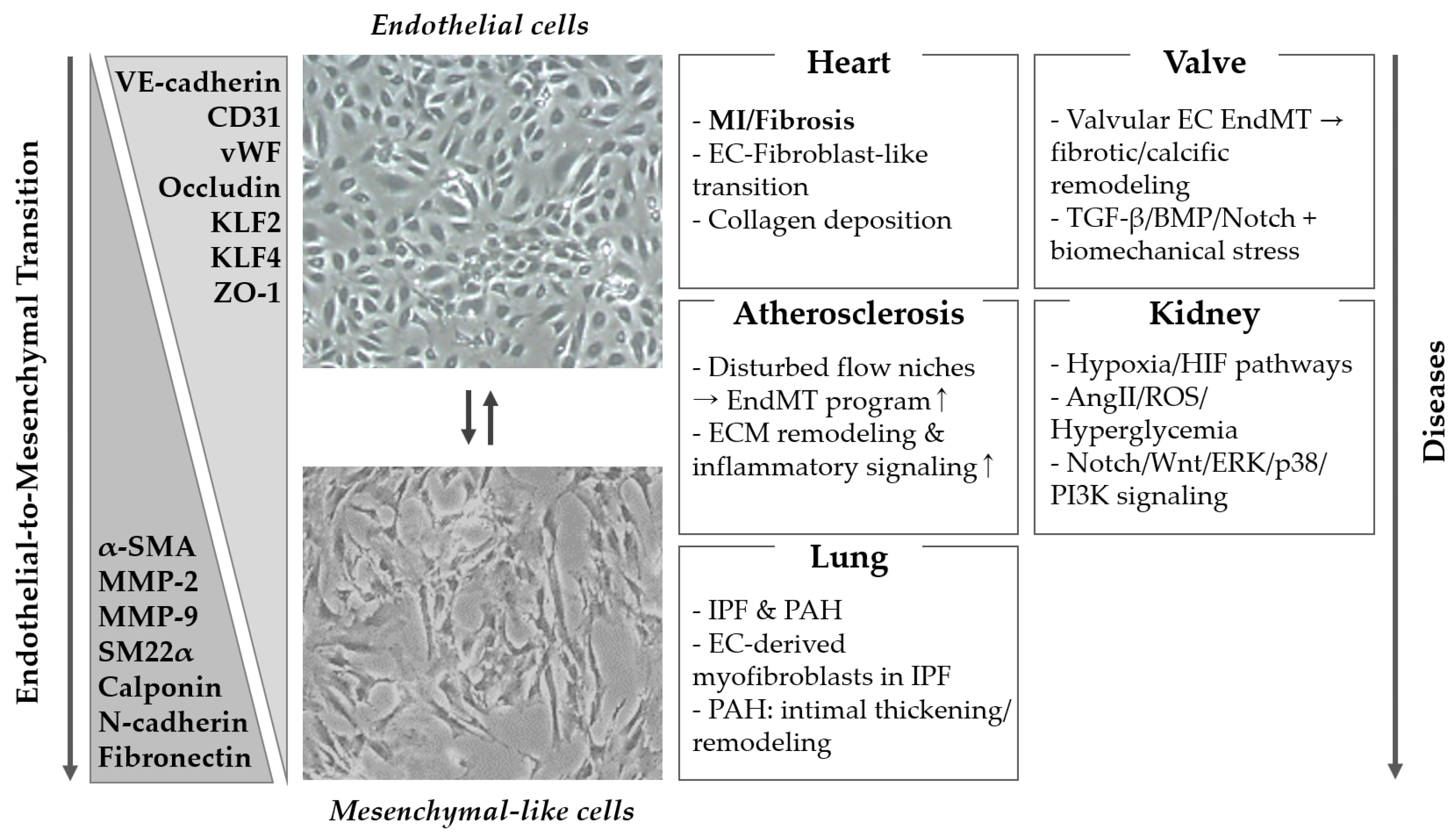

3. Organ System Pathologies Associated with EndMT

3.1. Cardiovascular System

3.2. Lung

3.3. Kidney

3.4. Liver

3.5. Central Nervous System

3.6. Tumor Microenvironment

4. Disease Models and Assessment Methods for EndMT

4.1. In Vitro Model Systems

4.1.1. Mechanochemical Stimulation-Based Models

4.1.2. Two-Dimensional Monolayer Culture Models

4.1.3. Three-Dimensional Models and Organoid Systems

4.1.4. Hypoxia-Based In Vitro Models

4.2. In Vivo Model Systems

4.3. EndMT Detection and Quantification Methods

4.3.1. Marker-Panels and 3D Tissue Imaging

4.3.2. EndMT Fate Mapping and Transcriptional Resolution

4.4. Organ-Specific Considerations for EndMT Models and Assessment

5. Therapeutic Regulation of EndMT

5.1. Signaling Pathway Inhibitors

5.1.1. Inhibition of the TGF-β Pathway

5.1.2. Modulation of Notch Signaling

5.1.3. Modulation of Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway

5.2. Epigenetic and ncRNA-Based Therapy Strategies

5.2.1. Epigenetic Inhibitors: HDAC and DNMT Inhibition

5.2.2. microRNA-Based Therapeutics

5.3. Antibodies and Biologic Agents

5.4. Small Molecule- and Compound-Based Strategies

5.5. Cell- and Gene-Based Therapeutic Strategies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ApoE | Apolipoprotein E |

| BBB | Blood–Brain Barrier |

| CBP | CREB-Binding Protein |

| CCM | Cerebral Cavernous Malformation |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CREB | cAMP Response Element-Binding Transcription Factor |

| DNMT | DNA Methyltransferase |

| EC | Endothelial Cell |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| EndMT | Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| FITC | Fluorescein Isothiocyanate |

| HAEC | Human Aortic Endothelial Cell |

| HDAC | Histone Deacetylase |

| HIF | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor |

| HUVEC | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cell |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IPF | Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis |

| iPSC | Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MI | Myocardial Infarction |

| miR | microRNA |

| MMP | Matrix Metalloproteinase |

| PAH | Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension |

| PDGF | Platelet-Derived Growth Factor |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| scRNA-seq | Single Cell RNA Sequencing |

| TβR | Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Receptor |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-Beta |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| vWF | von Willebrand Factor |

References

- Peng, Z.; Shu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M. Endothelial Response to Pathophysiological Stress. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, e233–e243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qu, H.; Liu, B.; Chen, B.C.; Yang, Z.; Shi, D.Z.; Zhang, Y. Low or oscillatory shear stress and endothelial permeability in atherosclerosis. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1432719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aveleira, C.A.; Lin, C.M.; Abcouwer, S.F.; Ambrósio, A.F.; Antonetti, D.A. TNF-α Signals Through PKCζ/NF-κB to Alter the Tight Junction Complex and Increase Retinal Endothelial Cell Permeability. Diabetes 2010, 59, 2872–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawa, Y.; Sugimoto, Y.; Ueki, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Sato, A.; Nagato, T.; Yoshida, S. Effects of TNF-alpha on leukocyte adhesion molecule expressions in cultured human lymphatic endothelium. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2007, 55, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Talukder, M.A.H.; Gao, F. Oxidative Stress and Microvessel Barrier Dysfunction. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejana, E. Endothelial cell-cell junctions: Happy together. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 5, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pober, J.S.; Sessa, W.C. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, J.C.; Dimmeler, S.; Harvey, R.P.; Finkel, T.; Aikawa, E.; Krenning, G.; Baker, A.H. Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 190–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piera-Velazquez, S.; Jimenez, S.A. Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition: Role in Physiology and in the Pathogenesis of Human Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1281–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelova, A.; Berman, M.; Al Ghouleh, I. Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 891–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, E.M.; Potenta, S.E.; Sugimoto, H.; Zeisberg, M.; Kalluri, R. Fibroblasts in kidney fibrosis emerge via endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 2282–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Chen, B.; Dong, W.; Kong, M.; Fan, Z.; Yu, L.; Wu, D.; Lu, J.; Xu, Y. MKL1 promotes endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and liver fibrosis by activating TWIST1 transcription. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yang, H.; Wan, Y.; Yang, S.; Wu, J.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Jin, H.; He, Q.; Zhu, D.Y.; et al. Endothelial ETS1 inhibition exacerbate blood–brain barrier dysfunction in multiple sclerosis through inducing endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.; Wallace, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Kalyanasundaram, S.; Andalman, A.S.; Davidson, T.J.; Mirzabekov, J.J.; Zalocusky, K.A.; Mattis, J.; Denisin, A.K.; et al. Structural and molecular interrogation of intact biological systems. Nature 2013, 497, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Kovacic, J.C. Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2023, 85, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, E.; Okamoto, T.; Ito, A.; Kawamoto, E.; Asanuma, K.; Wada, K.; Shimaoka, M.; Takao, M.; Shimamoto, A. Substrate stiffness modulates endothelial cell function via the YAP-Dll4-Notch1 pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2021, 408, 112835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.W.; Jamalian, S.; Hsu, J.C.; Sheng, X.R.; Yang, X.; Yang, X.; Monemi, S.; Hassan, S.; Yadav, R.; Tuckwell, K.; et al. A Phase 1a Study to Evaluate Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of RO7303509, an Anti-TGFβ3 Antibody, in Healthy Volunteers. Rheumatol. Ther. 2024, 11, 755–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Fan, T.; Xiao, C.; Tian, H.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C.; He, J. TGF-β signaling in health, disease and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niessen, K.; Fu, Y.; Chang, L.; Hoodless, P.A.; McFadden, D.; Karsan, A. Slug is a direct Notch target required for initiation of cardiac cushion cellularization. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 182, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.M.; Kim, H.R.; Xing, R.; Hsiao, S.; Mammoto, A.; Chen, J.; Serbanovic-Canic, J.; Feng, S.; Bowden, N.P.; Maguire, R.; et al. TWIST1 Integrates Endothelial Responses to Flow in Vascular Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Jeong, S.; Moon, H.; Kim, J.; Song, B.W.; Chang, W. The antioxidant effects of decursin inhibit EndMT progression through PI3K/AKT/NF-κB and Smad signaling pathways. BMB Rep. 2025, 58, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecce, L.; Xu, Y.; V’Gangula, B.; Chandel, N.; Pothula, V.; Caudrillier, A.; Santini, M.P.; d’Escamard, V.; Ceholski, D.K.; Gorski, P.A.; et al. Histone deacetylase 9 promotes endothelial-mesenchymal transition and an unfavorable atherosclerotic plaque phenotype. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e131178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, S.F.; Heumüller, A.W.; Tombor, L.; Hofmann, P.; Muhly-Reinholz, M.; Fischer, A.; Günther, S.; Kokot, K.E.; Hassel, D.; Kumar, S.; et al. The histone demethylase JMJD2B regulates endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 4180–4187, Erratum in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Xu, X.; Zeisberg, M.; Zeisberg, E.M. DNMT1 and HDAC2 Cooperate to Facilitate Aberrant Promoter Methylation in Inorganic Phosphate-Induced Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Duffhues, G.; García de Vinuesa, A.; Ten Dijke, P. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cardiovascular diseases: Developmental signaling pathways gone awry. Dev. Dyn. 2018, 247, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Lu, M.F.; Schwartz, R.J.; Martin, J.F. Bmp2 is essential for cardiac cushion epithelial-mesenchymal transition and myocardial patterning. Development 2005, 132, 5601–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbara, T.; Sharifi, M.; Aboutaleb, N. Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition in the Cardiogenesis and Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2020, 16, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, A.; Horie, M.; Nagase, T. TGF-β Signaling in Lung Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meeteren, L.A.; Ten Dijke, P. Regulation of endothelial cell plasticity by TGF-β. Cell Tissue Res. 2011, 347, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, E.M.; Tarnavski, O.; Zeisberg, M.; Dorfman, A.L.; McMullen, J.R.; Gustafsson, E.; Chandraker, A.; Yuan, X.; Pu, W.T.; Roberts, A.B.; et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, D.; Yuan, P.; Li, J.; Yun, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ma, J.; Sun, L.; Ma, H.; et al. Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Calcific Aortic Valve Disease. Acta Cardiol. Sin. 2020, 36, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Paranya, G.; Vineberg, S.; Dvorin, E.; Kaushal, S.; Roth, S.J.; Rabkin, E.; Schoen, F.J.; Bischoff, J. Aortic Valve Endothelial Cells Undergo Transforming Growth Factor-β-Mediated and Non-Transforming Growth Factor-β-Mediated Transdifferentiation in Vitro. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 159, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, D.; Potenta, S.; Kalluri, R. Transforming growth factor-β2 promotes Snail-mediated endothelial–mesenchymal transition through convergence of Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signaling. Biochem. J. 2011, 437, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tojo, M.; Hamashima, Y.; Hanyu, A.; Kajimoto, T.; Saitoh, M.; Miyazono, K.; Node, M.; Imamura, T. The ALK-5 inhibitor A-83--01 inhibits Smad signaling and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition by transforming growth factor-β. Cancer Sci. 2005, 96, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budi, E.H.; Schaub, J.R.; Decaris, M.; Turner, S.; Derynck, R. TGF-β as a driver of fibrosis: Physiological roles and therapeutic opportunities. J. Pathol. 2021, 254, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.Z.; Jiménez, J.M.; Ou, K.; McCormick, M.E.; Zhang, L.D.; Davies, P.F. Hemodynamic disturbed flow induces differential DNA methylation of endothelial Kruppel-Like Factor 4 promoter in vitro and in vivo. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andueza, A.; Kumar, S.; Kim, J.; Kang, D.W.; Mumme, H.L.; Perez, J.I.; Villa-Roel, N.; Jo, H. Endothelial Reprogramming by Disturbed Flow Revealed by Single-Cell RNA and Chromatin Accessibility Study. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, J.J.; Mosqueiro, T.S.; Archer, B.J.; Jones, W.M.; Sunshine, H.; Faas, G.C.; Briot, A.; Aragón, R.L.; Su, T.; Romay, M.C.; et al. NOTCH1 is a mechanosensor in adult arteries. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souilhol, C.; Tardajos Ayllon, B.; Li, X.; Diagbouga, M.R.; Zhou, Z.; Canham, L.; Roddie, H.; Pirri, D.; Chambers, E.V.; Dunning, M.J.; et al. JAG1-NOTCH4 mechanosensing drives atherosclerosis. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabo7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Niu, W.; Dong, H.Y.; Liu, M.L.; Luo, Y.; Li, Z.C. Hypoxia induces endothelial-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Takeda, N. The roles of HIF-1α signaling in cardiovascular diseases. J. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammoto, A.; Hendee, K.; Muyleart, M.; Mammoto, T. Endothelial Twist1-PDGFB signaling mediates hypoxia-induced proliferation and migration of αSMA-positive cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, C.; Yang, F.; Jiang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yao, W.; Pang, W.; Zhou, J. DNMT1 mediates the disturbed flow-induced endothelial to mesenchymal transition through disrupting β-alanine and carnosine homeostasis. Theranostics 2023, 13, 4392–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Shang, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, G.; Jin, Z.; Yao, F.; Yue, Z.; Bai, L.; Wang, R.; Zhao, S.; et al. HDAC3 inhibitor suppresses endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via modulating inflammatory response in atherosclerosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 192, 114716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanchin, B.; Sol, M.; Gjaltema, R.A.F.; Brinker, M.; Kiers, B.; Pereira, A.C.; Harmsen, M.C.; Moonen, J.A.J.; Krenning, G. Reciprocal regulation of endothelial–mesenchymal transition by MAPK7 and EZH2 in intimal hyperplasia and coronary artery disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fledderus, J.; Brouwer, L.; Kuiper, T.; Harmsen, M.C.; Krenning, G. H3K27Me3 abundance increases fibrogenesis during endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via the silencing of microRNA-29c. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 11, 1373279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Cao, Y.; Chen, S.; Chu, X.; Chu, Y.; Chakrabarti, S. miR-200b Mediates Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Diabetes 2016, 65, 768–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korpal, M.; Lee, E.S.; Hu, G.; Kang, Y. The miR-200 family inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer cell migration by direct targeting of E-cadherin transcriptional repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 14910–14914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarswamy, R.; Volkmann, I.; Jazbutyte, V.; Dangwal, S.; Park, D.H.; Thum, T. Transforming growth factor-β-induced endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition is partly mediated by microRNA-21. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Yao, Y.; Shi, S.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, M.; Chiu, J.J.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, M.; et al. Inhibition of miR-21 alleviated cardiac perivascular fibrosis via repressing EndMT in T1DM. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbineni, H.; Verma, A.; Artham, S.; Anderson, D.; Amaka, O.; Liu, F.; Narayanan, S.P.; Somanath, P.R. Pharmacological inhibition of β-catenin prevents EndMT in vitro and vascular remodeling in vivo resulting from endothelial Akt1 suppression. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 164, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami, K.H.; Nguyen, C.; Ma, H.; Kim, D.H.; Jeong, K.W.; Eguchi, M.; Moon, R.T.; Teo, J.L.; Kim, H.Y.; Moon, S.H.; et al. A small molecule inhibitor of beta-catenin/CREB-binding protein transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 12682–12687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, H.; Sato, S.; Koyama, K.; Morizumi, S.; Abe, S.; Azuma, M.; Chen, Y.; Goto, H.; Aono, Y.; Ogawa, H.; et al. The novel inhibitor PRI-724 for Wnt/β-catenin/CBP signaling ameliorates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Exp. Lung Res. 2019, 45, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, T.; Nagaoka, T.; Yoshida, T.; Wang, L.; Kuriyama, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Nagata, Y.; Harada, N.; Kodama, Y.; Takahashi, F.; et al. Nintedanib ameliorates experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension via inhibition of endothelial mesenchymal transition and smooth muscle cell proliferation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Fujimaki-Shiraishi, M.; Uchida, N.; Takemasa, A.; Niho, S. A Protective Effect of Pirfenidone in Lung Fibroblast–Endothelial Cell Network via Inhibition of Rho-Kinase Activity. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.K.; Chen, W.C.; Su, V.Y.; Shen, H.C.; Wu, H.H.; Chen, H.; Yang, K.Y. Nintedanib Inhibits Endothelial Mesenchymal Transition in Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis via Focal Adhesion Kinase Activity Reduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Muragaki, Y.; Saika, S.; Roberts, A.B.; Ooshima, A. Targeted disruption of TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling protects against renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobaczewski, M.; Chen, W.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Transforming Growth Factor (TGF)-β signaling in cardiac remodeling. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 51, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Mu, J.; Zeng, Q.; Deng, S.; Zhou, H. Signaling pathways in cancer-associated fibroblasts and targeted therapy for cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciszewski, W.M.; Wawro, M.E.; Sacewicz-Hofman, I.; Sobierajska, K. Cytoskeleton Reorganization in EndMT—The Role in Cancer and Fibrotic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.J.; Zhou, D.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Y. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and kidney fibrosis. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2014, 4, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Sanchez-Duffhues, G.; Goumans, M.J.; Ten Dijke, P. TGF-β-Induced Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Disease and Tissue Engineering. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Xiang, H.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, S.; Shu, Z.; Chai, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; et al. S1PR2/Wnt3a/RhoA/ROCK1/β-catenin signaling pathway promotes diabetic nephropathy by inducting endothelial mesenchymal transition and impairing endothelial barrier function. Life Sci. 2023, 328, 121853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Chen, L.; Zang, J.; Tang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, L.; Yin, Q.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, J.; et al. C3a and C5a receptor antagonists ameliorate endothelial-myofibroblast transition via the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in diabetic kidney disease. Metabolism 2015, 64, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Xiao, J.; Niu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shu, G.; Yin, G. Wnt/β-catenin signalling: Function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebner, S.; Cattelino, A.; Gallini, R.; Rudini, N.; Iurlaro, M.; Piccolo, S.; Dejana, E. Beta-catenin is required for endothelial-mesenchymal transformation during heart cushion development in the mouse. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 166, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisagbonhi, O.; Rai, M.; Ryzhov, S.; Atria, N.; Feoktistov, I.; Hatzopoulos, A.K. Experimental myocardial infarction triggers canonical Wnt signaling and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Dis. Model. Mech. 2011, 4, 469–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qiao, X.; Tan, T.K.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Cao, Q.; Wang, Y.; et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 9-dependent Notch signaling contributes to kidney fibrosis through peritubular endothelial–mesenchymal transition. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciszewski, W.M.; Sobierajska, K.; Wawro, M.E.; Klopocka, W.; Chefczyńska, N.; Muzyczuk, A.; Siekacz, K.; Wujkowska, A.; Niewiarowska, J. The ILK-MMP9-MRTF axis is crucial for EndMT differentiation of endothelial cells in a tumor microenvironment. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2017, 1864, 2283–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xu, Y.; Fu, Q.; Chang, M.; Wang, Y.; Shang, X.; Wan, C.; Marymont, J.V.; Dong, Y. Notch inhibits chondrogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells by targeting Twist1. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 403, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibney, E.R.; Nolan, C.M. Epigenetics and gene expression. Heredity 2010, 105, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. MicroRNAs as critical regulators of the endothelial to mesenchymal transition in vascular biology. BMB Rep. 2018, 51, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Song, S.; Zha, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Wang, F. MeCP2 promotes endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human endothelial cells by downregulating BMP7 expression. Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 375, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fledderus, J.; Vanchin, B.; Rots, M.G.; Krenning, G. The Endothelium as a Target for Anti-Atherogenic Therapy: A Focus on the Epigenetic Enzymes EZH2 and SIRT1. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Choi, N.; Park, J.H.; Yoo, K.H. Contribution of histone deacetylases (HDACs) to the regulation of histone and non-histone proteins: Implications for fibrotic diseases. BMB Rep. 2025, 58, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.C.; Moonen, J.R.; Brinker, M.G.; Krenning, G. FGF2 inhibits endothelial–mesenchymal transition through microRNA-20a-mediated repression of canonical TGF-β signaling. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.I.; Katsura, A.; Mihira, H.; Horie, M.; Saito, A.; Miyazono, K. Regulation of TGF-β-mediated endothelial-mesenchymal transition by microRNA-27. J. Biochem. 2017, 161, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; He, W.; Xu, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Han, S.; Shen, D. The mechanism of TGF-β/miR-155/c-Ski regulates endothelial–mesenchymal transition in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37, BSR20160603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miscianinov, V.; Martello, A.; Rose, L.; Parish, E.; Cathcart, B.; Mitić, T.; Gray, G.A.; Meloni, M.; Al Haj Zen, A.; Caporali, A. MicroRNA-148b Targets the TGF-β Pathway to Regulate Angiogenesis and Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition during Skin Wound Healing. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 1996–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Gao, L.; Xiao, L.; Yao, R.; Du, B.; Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Liang, C.; Huang, Z.; et al. miR-222 inhibits cardiac fibrosis in diabetic mice heart via regulating Wnt/β-catenin-mediated endothelium to mesenchymal transition. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 2149–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Yang, M.; Afzal, T.A.; An, W.; Maguire, E.M.; He, S.; Luo, J.; Wang, X.; et al. miRNA-200c-3p promotes endothelial to mesenchymal transition and neointimal hyperplasia in artery bypass grafts. J. Pathol. 2021, 253, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Jiang, L. MiR-200c-3p promotes ox-LDL-induced endothelial to mesenchymal transition in human umbilical vein endothelial cells through SMAD7/YAP pathway. J. Physiol. Sci. 2021, 71, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terriaca, S.; Scioli, M.G.; Pisano, C.; Ruvolo, G.; Ferlosio, A.; Orlandi, A. miR-632 Induces DNAJB6 Inhibition Stimulating Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Fibrosis in Marfan Syndrome Aortopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangwung, P.; Zhou, G.; Nayak, L.; Chan, E.R.; Kumar, S.; Kang, D.W.; Zhang, R.; Liao, X.; Lu, Y.; Sugi, K.; et al. KLF2 and KLF4 control endothelial identity and vascular integrity. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e91700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, M.; Hanai, J.; Sugimoto, H.; Mammoto, T.; Charytan, D.; Strutz, F.; Kalluri, R. BMP-7 counteracts TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and reverses chronic renal injury. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, A.R.; Huckaby, L.V.; Shiva, S.S.; Zuckerbraun, B.S. Nitric Oxide and Endothelial Dysfunction. Crit. Care Clin. 2020, 36, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, Q.D.; Chen, A.F.; Sun, K.; Lui, K.O.; Zhou, B. Seamless Genetic Recording of Transiently Activated Mesenchymal Gene Expression in Endothelial Cells During Cardiac Fibrosis. Circulation 2021, 144, 2004–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, P.; Christia, P.; Saxena, A.; Su, Y.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Lack of specificity of fibroblast-specific protein 1 in cardiac remodeling and fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013, 305, H1363–H1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Jin, H.; Zhou, B. Genetic lineage tracing with multiple DNA recombinases: A user’s guide for conducting more precise cell fate mapping studies. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 6413–6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S.; De Val, S.; Neal, A. Endothelial-Specific Cre Mouse Models. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 2550–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppe, C.; Ramirez Flores, R.O.; Li, Z.; Hayat, S.; Levinson, R.T.; Liao, X.; Hannani, M.T.; Tanevski, J.; Wünnemann, F.; Nagai, J.S.; et al. Spatial multi-omic map of human myocardial infarction. Nature 2022, 608, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreb, C.; Wolock, S.; Tusi, B.K.; Socolovsky, M.; Klein, A.M. Fundamental limits on dynamic inference from single-cell snapshots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2467–E2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, D.; Battistoni, G.; Hannon, G.J. The dawn of spatial omics. Science 2023, 381, eabq4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, E.M.; Potenta, S.; Xie, L.; Zeisberg, M.; Kalluri, R. Discovery of endothelial to mesenchymal transition as a source for carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 10123–10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddaluno, L.; Rudini, N.; Cuttano, R.; Bravi, L.; Giampietro, C.; Corada, M.; Ferrarini, L.; Orsenigo, F.; Papa, E.; Boulday, G.; et al. EndMT contributes to the onset and progression of cerebral cavernous malformations. Nature 2013, 498, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvandi, Z.; Bischoff, J. Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cardiovascular Disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 2357–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseling, M.; Sakkers, T.R.; De Jager, S.C.A.; Pasterkamp, G.; Goumans, M.J. The morphological and molecular mechanisms of epithelial/endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition and its involvement in atherosclerosis. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2018, 106, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Cui, C.; Wang, X. Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition: Role in Cardiac Fibrosis. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 26, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Hui, H.; Li, Z.; Pan, J.; Jiang, X.; Wei, T.; Cui, H.; Li, L.; Yuan, X.; Sun, T.; et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor attenuates myocardial fibrosis via inhibiting Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in rats with acute myocardial infarction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garside, V.C.; Chang, A.C.; Karsan, A.; Hoodless, P.A. Co-ordinating Notch, BMP, and TGF-β signaling during heart valve development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 2899–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, G.J.; Frendl, C.M.; Cao, Q.; Butcher, J.T. Effects of shear stress pattern and magnitude on mesenchymal transformation and invasion of aortic valve endothelial cells. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2014, 111, 2326–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Singh, P.; Shami, A.; Kluza, E.; Pan, M.; Djordjevic, D.; Michaelsen, N.B.; Kennbäck, C.; van der Wel, N.N.; Orho-Melander, M.; et al. Spatial Transcriptional Mapping Reveals Site-Specific Pathways Underlying Human Atherosclerotic Plaque Rupture. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.G.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, Q.Q.; Zhang, N.; Fan, D.; Che, Y.; Wang, Z.P.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, S.S.; Tang, Q.Z. Puerarin Protects against Cardiac Fibrosis Associated with the Inhibition of TGF- β 1/Smad2-Mediated Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. PPAR Res. 2017, 2017, 2647129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Kong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Guo, J.; Xu, Y. Dual roles of chromatin remodeling protein BRG1 in angiotensin II-induced endothelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimatsu, Y.; Wakabayashi, I.; Kimuro, S.; Takahashi, N.; Takahashi, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Maishi, N.; Podyma-Inoue, K.A.; Hida, K.; Miyazono, K.; et al. TNF-α enhances TGF-β-induced endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via TGF-β signal augmentation. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 2385–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, J.; Mitchell, J.A.; Jenkins, R.G. Beyond epithelial damage: Vascular and endothelial contributions to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, A.V.; Lu, W.; Dey, S.; Bhattarai, P.; Haug, G.; Larby, J.; Chia, C.; Jaffar, J.; Westall, G.; Singhera, G.K.; et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition: A precursor to pulmonary arterial remodelling in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. ERJ Open Res. 2023, 9, 00487–02022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, W.; Wang, Z.; Gao, C.; Wu, J.; Wu, Q. Trajectory modeling of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition reveals galectin-3 as a mediator in pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenmark, K.R.; Frid, M.; Perros, F. Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition: An Evolving Paradigm and a Promising Therapeutic Target in PAH. Circulation 2016, 133, 1734–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrot, D.; Dussaule, J.C.; Kavvadas, P.; Boffa, J.J.; Chadjichristos, C.E.; Chatziantoniou, C. Progression of renal fibrosis: The underestimated role of endothelial alterations. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012, 5 (Suppl. 1), S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, A.; Liu, Y. Targeting Hypoxia Inducible Factors-1α As a Novel Therapy in Fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Li, X.; Zhong, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, D.; Zhu, M.; Miao, C. KMT5A downregulation participated in High Glucose-mediated EndMT via Upregulation of ENO1 Expression in Diabetic Nephropathy. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 4093–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Duan, N.; Wang, Y.; Shu, S.; Xiang, X.; Guo, T.; Yang, L.; Zhang, S.; Tang, X.; Zhang, J. Advanced oxidation protein products induce endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human renal glomerular endothelial cells through induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2016, 30, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, B.; Duan, J.L.; Xu, H.; Tao, K.S.; Han, H.; Dou, G.R.; Wang, L. Capillarized Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells Undergo Partial Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition to Actively Deposit Sinusoidal ECM in Liver Fibrosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 671081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribera, J.; Pauta, M.; Melgar-Lesmes, P.; Córdoba, B.; Bosch, A.; Calvo, M.; Rodrigo-Torres, D.; Sancho-Bru, P.; Mira, A.; Jiménez, W.; et al. A small population of liver endothelial cells undergoes endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in response to chronic liver injury. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2017, 313, G492–G504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, M.; Aoki, H.; Hashita, T.; Iwao, T.; Matsunaga, T. Inhibition of transforming growth factor beta signaling pathway promotes differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived brain microvascular endothelial-like cells. Fluids Barriers CNS 2020, 17, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.A.; Kisseleva, T.; Scholten, D.; Paik, Y.H.; Iwaisako, K.; Inokuchi, S.; Schnabl, B.; Seki, E.; De Minicis, S.; Oesterreicher, C.; et al. Origin of myofibroblasts in liver fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012, 5 (Suppl. 1), S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Kong, M.; Zhu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Wu, D.; Lu, J.; Guo, J.; Xu, Y. Activation of TWIST Transcription by Chromatin Remodeling Protein BRG1 Contributes to Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derada Troletti, C.; Fontijn, R.D.; Gowing, E.; Charabati, M.; van Het Hof, B.; Didouh, I.; van der Pol, S.M.A.; Geerts, D.; Prat, A.; van Horssen, J.; et al. Inflammation-induced endothelial to mesenchymal transition promotes brain endothelial cell dysfunction and occurs during multiple sclerosis pathophysiology. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potenta, S.; Zeisberg, E.; Kalluri, R. The role of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer progression. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 99, 1375–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.X.; Chenm, J.X.; Zheng, Z.J.; Cai, W.J.; Yang, X.B.; Huang, Y.Y.; Gong, Y.; Xu, F.; Chen, Y.S.; Lin, L. TGF-β1 promotes human breast cancer angiogenesis and malignant behavior by regulating endothelial-mesenchymal transition. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1051148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacic, J.C.; Mercader, N.; Torres, M.; Boehm, M.; Fuster, V. Epithelial- and Endothelial- to Mesenchymal Transition: From Cardiovascular Development to Disease. Circulation 2012, 125, 1795–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Boström, K.I.; Di Carlo, D.; Simmons, C.A.; Tintut, Y.; Yao, Y.; Hsu, J.J. The Mechanobiology of Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 734215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombor, L.S.; John, D.; Glaser, S.F.; Luxán, G.; Forte, E.; Furtado, M.; Rosenthal, N.; Baumgarten, N.; Schulz, M.H.; Wittig, J.; et al. Single cell sequencing reveals endothelial plasticity with transient mesenchymal activation after myocardial infarction. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimouni, M.; Lajoix, A.D.; Desmetz, C. Experimental Models to Study Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Myocardial Fibrosis and Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, K.; Grover, H.; Han, L.H.; Mou, Y.; Pegoraro, A.F.; Fredberg, J.; Chen, Z. Modeling Physiological Events in 2D vs. 3D Cell Culture. Physiology 2017, 32, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthika, C.L.; Venugopal, V.; Sreelakshmi, B.J.; Krithika, S.; Thomas, J.M.; Abraham, M.; Kartha, C.C.; Rajavelu, A.; Sumi, S. Oscillatory shear stress modulates Notch-mediated endothelial mesenchymal plasticity in cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2023, 28, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañez, E.; Casaroli-Marano, R.P.; Vilaró, S.; Pagan, R. Comparative study of tube assembly in three-dimensional collagen matrix and on Matrigel coats. Angiogenesis 2002, 5, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi-Meshkin, H.; Cornelius, V.A.; Eleftheriadou, M.; Potel, K.N.; Setyaningsih, W.A.W.; Margariti, A. Vascular organoids: Unveiling advantages, applications, challenges, and disease modelling strategies. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xu, Z.; Xiao, L.; Shi, T.; Xiao, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xue, F.; Zeng, W. Review on the Vascularization of Organoids and Organoids-on-a-Chip. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 637048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, L.; Suijker, J.; van Roey, R.; Berges, N.; Petrova, E.; Queiroz, K.; Strijker, W.; Olivier, T.; Poeschke, O.; Garg, S.; et al. A Microfluidic 3D Endothelium-on-a-Chip Model to Study Transendothelial Migration of T Cells in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrycky, C.J.; Howard, C.C.; Rayner, S.G.; Shin, Y.J.; Zheng, Y. Organ-on-a-chip systems for vascular biology. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2021, 159, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisanuki, Y.Y.; Hammer, R.E.; Miyazaki, J.; Williams, S.C.; Richardson, J.A.; Yanagisawa, M. Tie2-Cre transgenic mice: A new model for endothelial cell-lineage analysis in vivo. Dev. Biol. 2001, 230, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monvoisin, A.; Alva, J.A.; Hofmann, J.J.; Zovein, A.C.; Lane, T.F.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L. VE-cadherin-CreERT2 transgenic mouse: A model for inducible recombination in the endothelium. Dev. Dyn. 2006, 235, 3413–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madisen, L.; Zwingman, T.A.; Sunkin, S.M.; Oh, S.W.; Zariwala, H.A.; Gu, H.; Ng, L.L.; Palmiter, R.D.; Hawrylycz, M.J.; Jones, A.R.; et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2010, 13, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessalles, C.A.; Leclech, C.; Castagnino, A.; Barakat, A.I. Integration of substrate- and flow-derived stresses in endothelial cell mechanobiology. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, S.; Kim, T.Y.; Jung, E.; Shin, S.Y. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase contributes to TNFα-induced endothelial tube formation of bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by activating the JAK/STAT/TIE2 signaling axis. BMB Rep. 2024, 57, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaço-Guidolin, L.; Rosin, N.L.; Hackett, T.L. Imaging Collagen in Scar Tissue: Developments in Second Harmonic Generation Microscopy for Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, J.X. Microvascular Rarefaction and Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytil, A.; Magnuson, M.A.; Wright, C.V.; Moses, H.L. Conditional inactivation of the TGF-beta type II receptor using Cre:Lox. Genesis 2002, 32, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.; Shinde, A.V.; Su, Y.; Russo, I.; Chen, B.; Saxena, A.; Conway, S.J.; Graff, J.M.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Opposing Actions of Fibroblast and Cardiomyocyte Smad3 Signaling in the Infarcted Myocardium. Circulation 2018, 137, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Shi, W.; Wang, Y.L.; Chen, H.; Bringas, P., Jr.; Datto, M.B.; Frederick, J.P.; Wang, X.F.; Warburton, D. Smad3 deficiency attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2002, 282, L585–L593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, C.P.; Choi, S.Y.; Kee, Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, Y.; Park, H.C.; Ro, H. Transgenic fluorescent zebrafish lines that have revolutionized biomedical research. Lab. Anim. Res. 2021, 37, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.S.; Keyser, M.S.; Gurevich, D.B.; Sturtzel, C.; Mason, E.A.; Paterson, S.; Chen, H.; Scott, M.; Condon, N.D.; Martin, P.; et al. Live-imaging of endothelial Erk activity reveals dynamic and sequential signalling events during regenerative angiogenesis. eLife 2021, 10, e62196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Moyse, B.R.; Richardson, R.J. Zebrafish cardiac regeneration-looking beyond cardiomyocytes to a complex microenvironment. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 154, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmutovic Persson, I.; Falk Håkansson, H.; Örbom, A.; Liu, J.; von Wachenfeldt, K.; Olsson, L.E. Imaging Biomarkers and Pathobiological Profiling in a Rat Model of Drug-Induced Interstitial Lung Disease Induced by Bleomycin. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madisen, L.; Garner, A.R.; Shimaoka, D.; Chuong, A.S.; Klapoetke, N.C.; Li, L.; van der Bourg, A.; Niino, Y.; Egolf, L.; Monetti, C.; et al. Transgenic mice for intersectional targeting of neural sensors and effectors with high specificity and performance. Neuron 2015, 85, 942–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayr, C.H.; Santacruz, D.; Jarosch, S.; Bleck, M.; Dalton, J.; McNabola, A.; Lempp, C.; Neubert, L.; Rath, B.; Kamp, J.C.; et al. Spatial transcriptomic characterization of pathologic niches in IPF. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadl5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luecken, M.D.; Theis, F.J. Current best practices in single-cell RNA-seq analysis: A tutorial. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2019, 15, e8746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Brink, S.C.; Sage, F.; Vértesy, Á.; Spanjaard, B.; Peterson-Maduro, J.; Baron, C.S.; Robin, C.; van Oudenaarden, A. Single-cell sequencing reveals dissociation-induced gene expression in tissue subpopulations. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 935–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Engel, J.; Teichmann, S.A.; Lönnberg, T. A practical guide to single-cell RNA-sequencing for biomedical research and clinical applications. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, S.K.; Beauchamp, R.D.; Datta, P.K. A Specific Inhibitor of TGF-β Receptor Kinase, SB-431542, as a Potent Antitumor Agent for Human Cancers. Neoplasia 2005, 7, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbertz, S.; Sawyer, J.S.; Stauber, A.J.; Gueorguieva, I.; Driscoll, K.E.; Estrem, S.T.; Cleverly, A.L.; Desaiah, D.; Guba, S.C.; Benhadji, K.A.; et al. Clinical development of galunisertib (LY2157299 monohydrate), a small molecule inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 4479–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melisi, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Macarulla, T.; Pezet, D.; Deplanque, G.; Fuchs, M.; Trojan, J.; Oettle, H.; Kozloff, M.; Cleverly, A.; et al. Galunisertib plus gemcitabine vs. gemcitabine for first-line treatment of patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.A.; Lam, M.T.; Wu, X.; Kim, T.N.; Vartanian, S.M.; Bollen, A.W.; Carlson, T.R.; Wang, R.A. Endothelial Notch4 signaling induces hallmarks of brain arteriovenous malformations in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10901–10906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dong, F.; Jia, Y.; Du, H.; Dong, N.; Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, W. Notch signal regulates corneal endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 183, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, M.; Pace, V.; Maiullari, F.; Chirivì, M.; Baci, D.; Maiullari, S.; Madaro, L.; Maccari, S.; Stati, T.; Marano, G.; et al. Givinostat reduces adverse cardiac remodeling through regulating fibroblasts activation. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, E.K.; Jordan, N.; Sheerin, N.S.; Ali, S. Regulation of Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition by microRNAs in Chronic Allograft Dysfunction. Transplantation 2019, 103, e64–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, I.S.; Kwon, K. Potential application of biomimetic exosomes in cardiovascular disease: Focused on ischemic heart disease. BMB Rep. 2022, 55, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.W.; Guzman, E.B.; Menon, N.; Langer, R.S. Lipid Nanoparticles for Nucleic Acid Delivery to Endothelial Cells. Pharm. Res. 2023, 40, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosta, P.; Tamargo, I.; Ramos, V.; Kumar, S.; Kang, D.W.; Borrós, S.; Jo, H. Delivery of Anti-miR-712 to Inflamed Endothelial Cells Using Poly(β-amino ester) Nanoparticles Conjugated with VCAM-1 Targeting Peptide. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, e2001894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhiz, H.; Shuvaev, V.V.; Pardi, N.; Khoshnejad, M.; Kiseleva, R.Y.; Brenner, J.S.; Uhler, T.; Tuyishime, S.; Mui, B.L.; Tam, Y.K.; et al. PECAM-1 directed re-targeting of exogenous mRNA providing two orders of magnitude enhancement of vascular delivery and expression in lungs independent of apolipoprotein E-mediated uptake. J. Control. Release 2018, 291, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.M.; Padilla, C.M.; McLaughlin, S.R.; Mathes, A.; Ziemek, J.; Goummih, S.; Nakerakanti, S.; York, M.; Farina, G.; Whitfield, M.L.; et al. Fresolimumab treatment decreases biomarkers and improves clinical symptoms in systemic sclerosis patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 2795–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripska, K.; Igreja Sá, I.C.; Vasinova, M.; Vicen, M.; Havelek, R.; Eissazadeh, S.; Svobodova, Z.; Vitverova, B.; Theuer, C.; Bernabeu, C.; et al. Monoclonal anti-endoglin antibody TRC105 (carotuximab) prevents hypercholesterolemia and hyperglycemia-induced endothelial dysfunction in human aortic endothelial cells. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 845918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoonderwoerd, M.J.A.; Goumans, M.T.H.; Hawinkels, L.J.A.C. Endoglin: Beyond the Endothelium. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielpour, D. Advances and Challenges in Targeting TGF-β Isoforms for Therapeutic Intervention of Cancer: A Mechanism-Based Perspective. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, S.; Sanchez Duffhues, G.; Ten Dijke, P.; Baker, D. The therapeutic potential of targeting the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Angiogenesis 2019, 22, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordo, R.; Nasrallah, G.K.; Posadino, A.M.; Galimi, F.; Capobianco, G.; Eid, A.H.; Pintus, G. Resveratrol-Elicited PKC Inhibition Counteracts NOX-Mediated Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Human Retinal Endothelial Cells Exposed to High Glucose. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Shi, X.; Gao, Z.; Guo, Z. Curcumin attenuates endothelial cell fibrosis through inhibiting endothelial–interstitial transformation. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020, 47, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, R.; Gambhir, S.S.; Cooke, J.P. Endothelial cells derived from human iPSCs increase capillary density and improve perfusion in a mouse model of peripheral arterial disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, e72–e79. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.C.; Hsieh, M.L.; Lin, C.J.; Chang, C.M.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Puntney, R.; Wu Moy, A.; Ting, C.Y.; Herr Chan, D.Z.; Nicholson, M.W.; et al. Combined Treatment of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes and Endothelial Cells Regenerate the Infarcted Heart in Mice and Non-Human Primates. Circulation 2023, 148, 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, C.B.; Fonager, S.V.; Haskó, J.; Helmig, R.B.; Degn, S.; Bolund, L.; Jessen, N.; Lin, L.; Luo, Y. HIF1A Knockout by Biallelic and Selection-Free CRISPR Gene Editing in Human Primary Endothelial Cells with Ribonucleoprotein Complexes. Biomolecules 2022, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazovic, B.; Nguyen, H.T.; Ansarizadeh, M.; Wigge, L.; Kohl, F.; Li, S.; Carracedo, M.; Kettunen, J.; Krimpenfort, L.; Elgendy, R.; et al. Human iPSC and CRISPR targeted gene knock-in strategy for studying the somatic TIE2L914F mutation in endothelial cells. Angiogenesis 2024, 27, 523–542, Erratum in Angiogenesis 2024, 27, 543–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovisa, S.; Fletcher-Sananikone, E.; Sugimoto, H.; Hensel, J.; Lahiri, S.; Hertig, A.; Taduri, G.; Lawson, E.; Dewar, R.; Revuelta, I.; et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition compromises vascular integrity to induce Myc-mediated metabolic reprogramming in kidney fibrosis. Sci. Signal. 2020, 13, eaaz2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzolini, N.; Brysgel, T.V.; Essien, E.O.; Rahman, R.J.; Wu, J.; Majumder, A.; Patel, M.N.; Tiwari, S.; Espy, C.L.; Shuvaev, V.V.; et al. Targeting DNA-LNPs to Endothelial Cells Improves Expression Magnitude, Duration, and Specificity. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, I.F.; Kishta, F.; Xu, Y.; Baker, A.H.; Kovacic, J.C. Endothelial to mesenchymal transition: At the axis of cardiovascular health and disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 120, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, R.A.; Leopoldi, A.; Aichinger, M.; Wick, N.; Hantusch, B.; Novatchkova, M.; Taubenschmid, J.; Hämmerle, M.; Esk, C.; Bagley, J.A.; et al. Human blood vessel organoids as a model of diabetic vasculopathy. Nature 2019, 565, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeri, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Landau, S.; Perera, K.; Lee, J.; Radisic, M. Engineering organ-on-a-chip systems for vascular diseases. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2023, 43, 2241–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, L.; You, Z.; Lu, L.; Xu, T.; Sarkar, A.K.; Zhu, H.; Liu, M.; Calandrelli, R.; Yoshida, G.; Lin, P.; et al. Modeling blood-brain barrier formation and cerebral cavernous malformations in human PSC-derived organoids. Cell Stem Cell 2024, 31, 818–833.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheroni, C.; Trattaro, S.; Caporale, N.; López-Tobón, A.; Tenderini, E.; Sebastiani, S.; Troglio, F.; Gabriele, M.; Bressan, R.B.; Pollard, S.M.; et al. Benchmarking brain organoid recapitulation of fetal corticogenesis. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.S.; Hultgren, N.W.; Hughes, C.C.W. Regulation of Partial and Reversible Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Angiogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 702021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.G.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, T. Nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery in the vascular system: Focus on endothelium. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, Y.; Tang, F.; Peng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, H. TGF-beta signal transduction: Biology, function and therapy for diseases. Mol. Biomed. 2022, 3, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inducer/ Stimulus | Major Pathway | Key TFs/ Regulators | Core Readouts | Disease Context | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β | TβR1→SMAD2/3; PI3K/AKT, p38/JNK | SNAI1/2 TWIST1 ZEB1/2 | ↓CD31/VE-cadherin; ↑α-SMA, FN1, COL1A1 | Cardiac fibrosis and valvular disease, aortic aneurysms, renal and pulmonary fibrosis | [8,15,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] |

| TNF-α/IL-1β | NF-κB, MAPKs | NF-κB (p65) | Barrier loss (TEER↓), Leukocyte adhesion↑; Synergizes with TGF-β to promote EndMT | Inflammatory vasculopathies, atherosclerosis | [3,5,7] |

| Disturbed/ oscillatory shear | Notch1, JAG-NOTCH4; DNMT1-mediated KLF4 promoter methylation | TWIST1 NOTCH1/4 DNMT1 | EndMT program↑ EC identity↓ | Atherosclerosis | [2,20,36,37,38,39] |

| Hypoxia | HIF-1α→TIWST1-PDGFB axis | HIF-1α TWIST1 | EndMT markers↑ (α-SMA, FN1, SNAI1/2) | PAH, lung remodeling | [10,40,41,42] |

| Epigenetic regulation | HDAC9/HDAC3;DNMT1; JMJD2B;EZH2/H3K27me3 | HDAC9/3 DNMT1 JMJD2B EZH2 | H3K27me3 changes, KLF4 promoter methylation↑, miR-29c silencing | Atherosclerosis, Neointima, Fibrosis | [22,23,24,43,44,45,46] |

| miR-200 family | Direct targeting of ZEB1/2→EMT/EndMT suppression | miR-200a/b/c | ZEB1/2↓, Maintenance of EC Identity | Diabetic complications, Fibrosis | [47,48] |

| miR-21 | Represses SMAD inhibitor→strengthens TGF-β | miR-21 | EndMT markers↑, anti-miR-21 attenuates EndMT | Perivascular/ Cardiac fibrosis | [49,50] |

| Wnt/β-catenin (Therapy) | Inhibition of β-catenin/CBP transcriptional complex | - | EndMT suppression, Improved vascular Remodeling | Pulmonary fibrosis, Vasculopathy | [51,52,53] |

| Small molecules/ natural products(Therapy) | Rho-kinase/FAK↓ | - | EndMT↓, Amelioration of fibrosis/PAH | Pulmonary fibrosis, PAH | [54,55,56] |

| Platform | Major Strengths | Key Limitations/Pitfalls | Minimal Reporting/ QC Items | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D EC monolayers | High control, scalable, Convenient/reproducible Baseline | Limited tissue context Over-simplify transient/partial states | Cell source/passage; inducer dose/time; marker panel; replicate design | [125,126] |

| Mechnochemicalmodels | Mimics shear/stiffness- driven programs | Device-to-device variability; sensitivity to setup; lab-to-lab reproducibility issues | Flow/shear parameters; substrate stiffness; calibration method | [38,127] |

| 2D ECM | Cell–matrix interaction, Structural remodeling | Matrix batch variability; limited cellular heterogeneity | Matrix composition/concentration; gel protocol; imaging quantification | [126,128] |

| iPSC-vascular organoids | Multicellular crosstalk, More physiological Gradients | Batch-to-batch variability; maturation state affects specificity | Differentiation QC; cell composition metrics; batch controls | [129,130] |

| Organ-on-a-chip/microfluidics | Controlled shear+ Real-time readouts | Fabrication/operation variability; throughput constraints | Device specs; shear profiles; barrier readouts; standardized operating protocol | [131,132] |

| In vivo disease models | System-level context, Causality testing | Species differences; model-specific confounders | Model details; time-course; endpoints; randomization/blinding if used | [125] |

| Endothelial lineagetracing | Lineage-informed “contribution” evidence | Recombination specificity/efficiency; time/dose confounds | Driver line; induction regimen; recombination efficiency controls | [133,134,135] |

| Marker panels | Widely accessible; quantitative protein-level calls | Specificity limited by marker overlap; single-marker false positives | Define “program-level” criteria; recombination efficiency controls | [8,9,88] |

| Tissue cleaning | Whole-organ 3D localization/quantification | Antibody penetration; signal-to-noise impacts sensitivity; protocol-dependent | Clearing protocol; imaging settings; segmentation method; validation modality | [14] |

| scRNA-seq/scATAC-seq | Unbiased state discovery; regulatory inference | Dropout/dissociation bias affects sensitivity; snapshot→trajectory inference | Cell numbers; QC metrics; batch correction; signature definitions | [37,92,124] |

| Spatial transcriptomics | Niche localization of putative transitions | Resolution limits; transcript capture affects sensitivity; snapshot inference | Platform/resolution; tissue handling; normalization; validation markers | [91,93] |

| Strategy/Mechanism | Representative Agents | Model & Readouts | Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathway inhibitors:TβR1/canonical SMAD | SB-431542, A-83-01; Galunisertib | ECs; MI/IPF/PAH models; marker panel | EndMT markers↓, migration↓; fibrosis burden↓ | [8,28,32,145,146,147,148,160] |

| Non-canonical:Rho/ROCK, FAK, PI3K/AKT, MAPK | ROCK/FAK inhibitors | Atheroprone-flow ECs; lung vascular models | Stress fiber↓, mesenchymal program↓ | [54,55,56] |

| Epigenetic:HDAC/DNMT/EZH2/JMJD2B | HDAC inhibitors; 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine | In vitro ECs; fibrosis models | Chromatin re-opening→EndMT↓ | [22,23,24,49,53,55,56] |

| miRNA therapeutics:restore anti-EndMT/block pro-miRs | miR-200b mimic; anti-miR-21 (LNP/exosome) | ECs, iPSC-ECs; injury models | ZEB1/2↓; EndMT↓; maintain EC identity | [47,58,63,84,157,158,159] |

| Biologics:anti-TGF-β/endoglinaxis | mAbs/ligand traps (context-dependent) | Fibrosis/PAH models | SMAD-driven EndMT↓ | [8,17,18,160,162] |

| Cell/Gene:iPSC-ECs; CRISPR edits | SNAI/ZEB KO; miR-cassettes KI | Graft stability assays; in vivo repair | EndMT resistance↑, preserve function | [72,128,129,130,131,132,133,138,139,170,171,172,173] |

| Natural products/small molecules:multi-pathway | Resveratrol; Curcumin | EC EndMT assays; fibrosis models | ROS/NF-κB↓;EndMT↓ | [168,169] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, R.; Chang, W. Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Health and Disease: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311724

Kim R, Chang W. Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Health and Disease: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311724

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Ran, and Woochul Chang. 2025. "Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Health and Disease: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Implications" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311724

APA StyleKim, R., & Chang, W. (2025). Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Health and Disease: Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311724