MicroRNA-1 Suppresses Tumor Progression and UHRF1 Expression in Cholangiocarcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

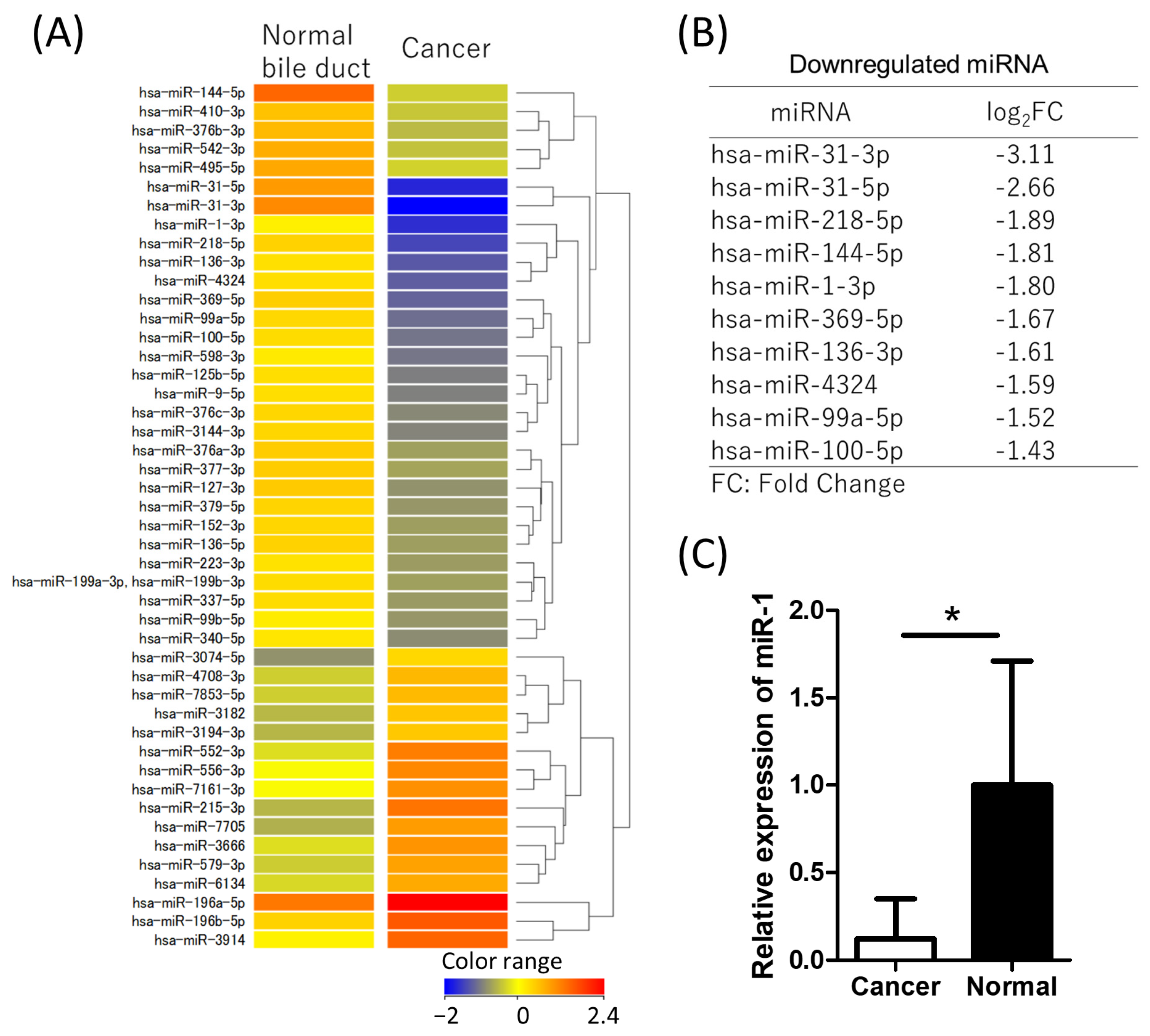

2.1. miR-1 Is Downregulated in CCA Tissue

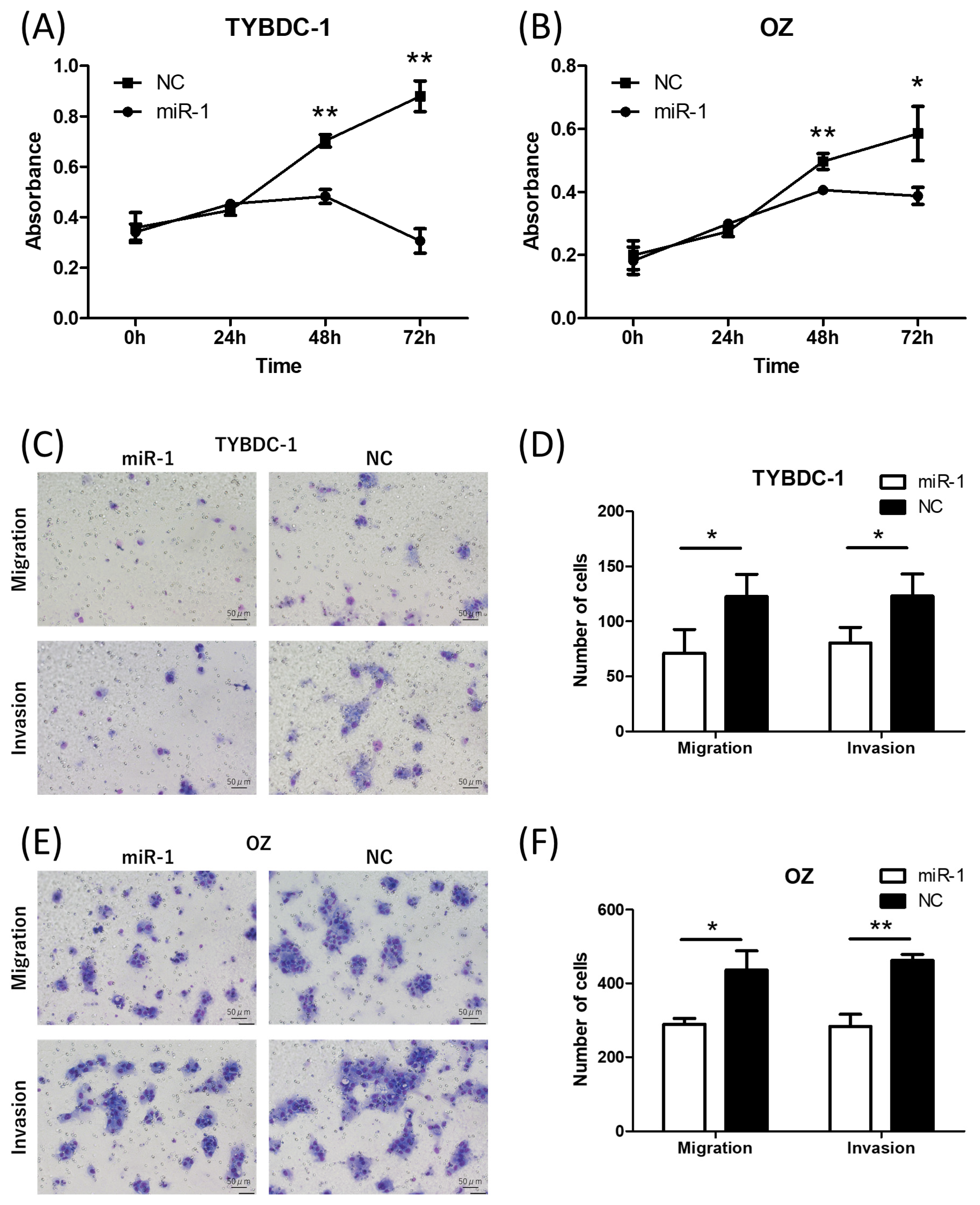

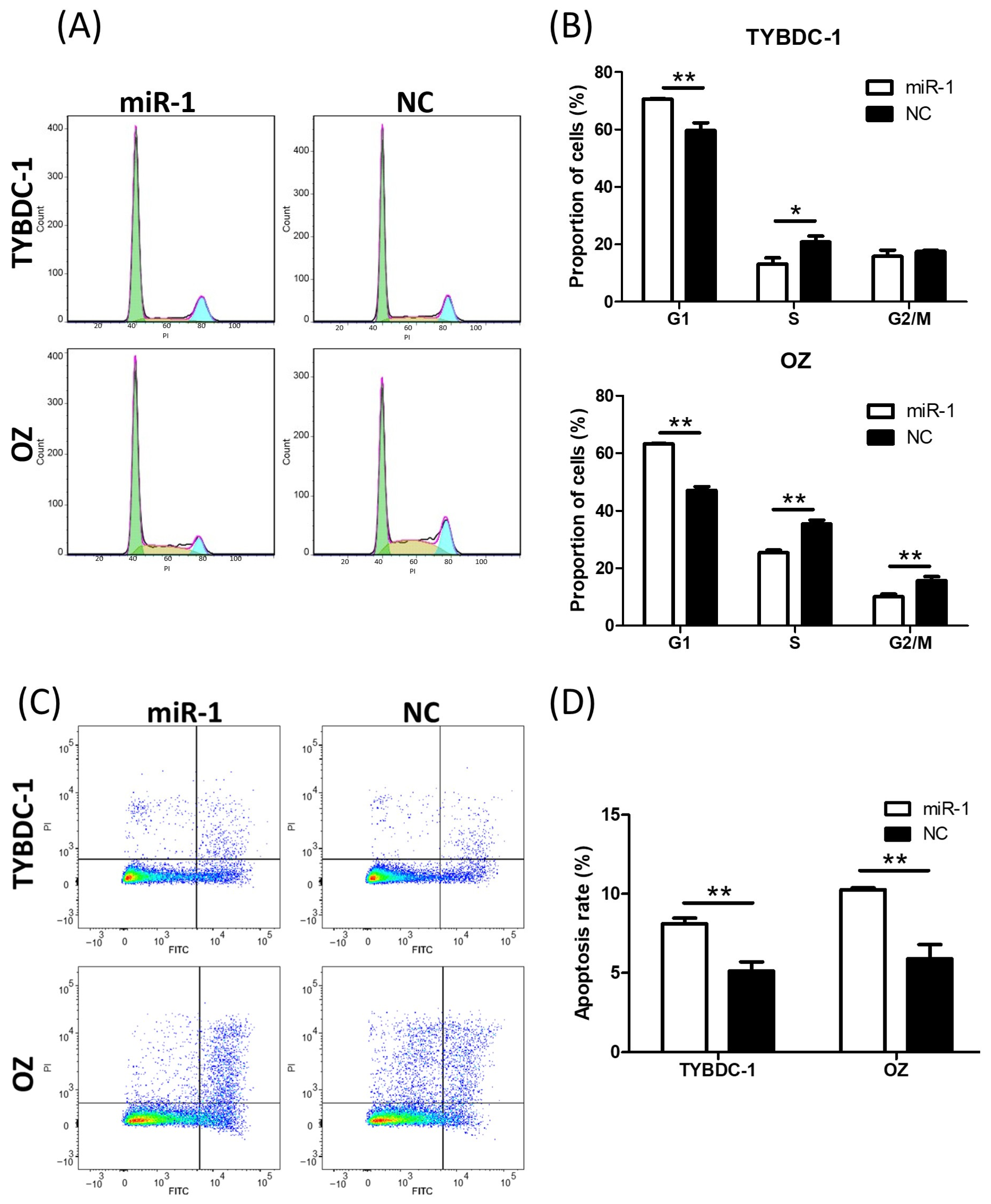

2.2. miR-1 Suppresses Cell Proliferation, Migration, Invasion, and Cell Cycle Progression, While Promoting Apoptosis in CCA Cell Lines

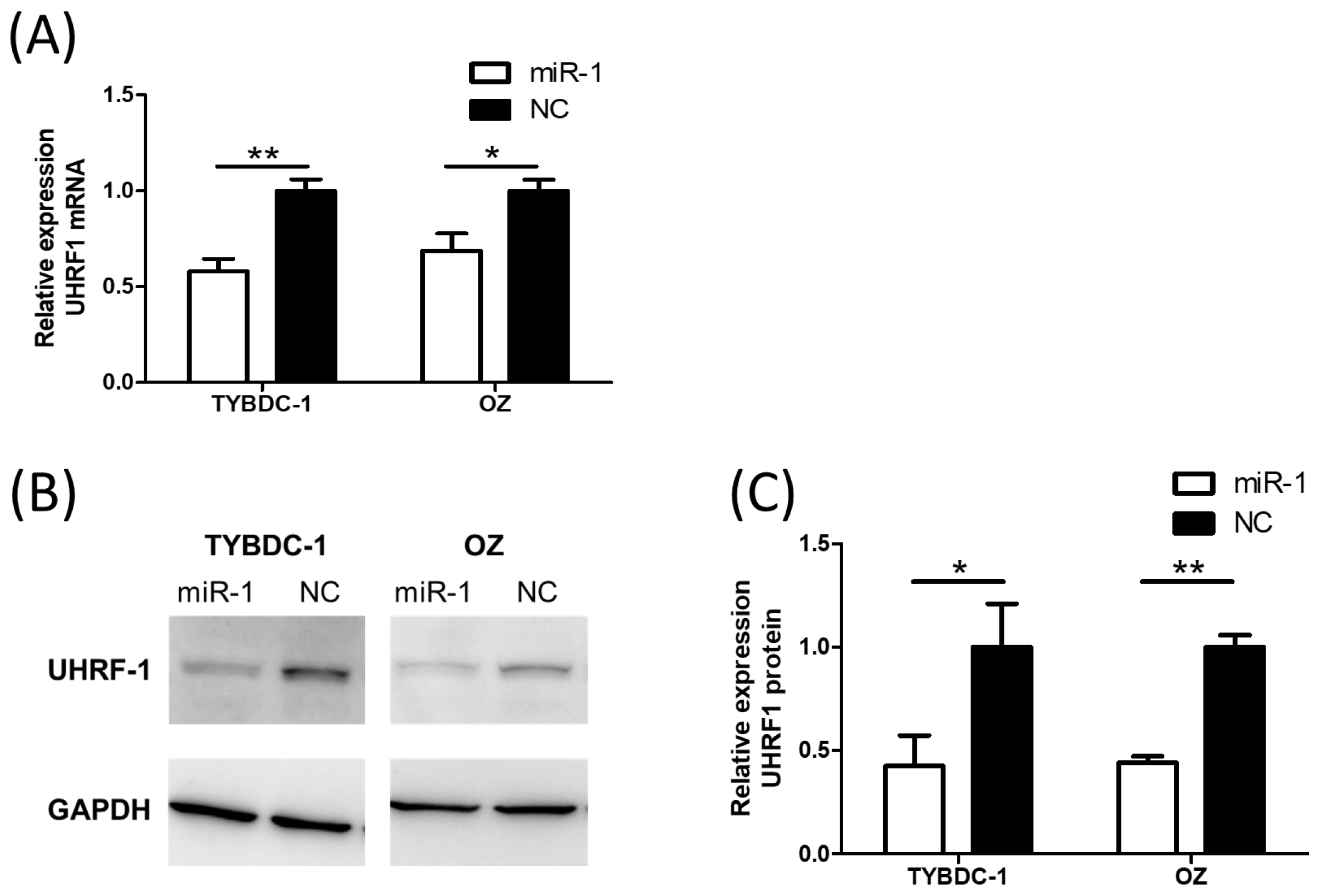

2.3. UHRF1 Expression Is Suppressed by miR-1 Transfection

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Method

4.1. Clinical Tissue Samples

4.2. miRNA and mRNA Microarray Analysis

4.3. Cell Culture and Transfection

4.4. RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

4.5. Proliferation Assay

4.6. Migration and Invasion Assay

4.7. Cell Cycle Assay

4.8. Apoptosis Assay

4.9. Prediction of miRNA Target Genes

4.10. Western Blotting Analysis

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3′UTR | 3′ untranslated region |

| AGMAT | agmatinase |

| API-5 | apoptosis inhibitor-5 |

| CCA | cholangiocarcinoma |

| CDH13 | cadherin 13 |

| CDK4/CDK6 | cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 |

| CENPF | centromere Protein F |

| C17orf78 | chromosome 17 open reading frame 78 |

| CpG | cytosine–phosphate–guanine |

| CXCR4 | C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 |

| DYNLT3 | dynein light chain Tctex-type 3 |

| GOLPH3 | Golgi phosphoprotein 3 |

| H3K9me2/3 | di- and tri-methylated lysine 9 of histone H3 |

| H3R2 | unmodified arginine 2 of histone H3 |

| HOTAIR | HOX antisense transcript RNA |

| IPA | Ingenuity Pathway Analysis |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| miR-1 | microRNA-1 |

| NETO2 | neuropilin and tolloid-like 2 |

| NF-kB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| PFTK1 | PFTAIRE protein kinase 1 |

| PI3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PTBP1 | polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative RT-PCR |

| RASSF1 | Ras association domain family member 1 |

| RRM2 | ribonucleotide reductase M2 |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| UHRF1 | ubiquitin-like with plant homeodomain and ring finger domains 1 |

References

- Brindley, P.J.; Bachini, M.; Ilyas, S.I.; Khan, S.A.; Loukas, A.; Sirica, A.E.; Teh, B.T.; Wongkham, S.; Gores, G.J. Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeOliveira, M.L.; Cunningham, S.C.; Cameron, J.L.; Kamangar, F.; Winter, J.M.; Lillemoe, K.D.; Choti, M.A.; Yeo, C.J.; Schulick, R.D. Cholangiocarcinoma: Thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann. Surg. 2007, 245, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagino, M.; Ebata, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Igami, T.; Sugawara, G.; Takahashi, Y.; Nimura, Y. Evolution of surgical treatment for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A single-center 34-year review of 574 consecutive resections. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spolverato, G.; Yakoob, M.Y.; Kim, Y.; Alexandrescu, S.; Marques, H.P.; Lamelas, J.; Aldrighetti, L.; Gamblin, T.C.; Maithel, S.K.; Pulitano, C.; et al. The Impact of Surgical Margin Status on Long-Term Outcome After Resection for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 4020–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebata, T.; Mizuno, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Igami, T.; Sugawara, G.; Nagino, M. Surgical resection for Bismuth type IV perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Br. J. Surg. 2018, 105, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buettner, S.; Ten Cate, D.W.G.; Bagante, F.; Alexandrescu, S.; Marques, H.P.; Lamelas, J.; Aldrighetti, L.; Gamblin, T.C.; Maithel, S.K.; Pulitano, C.; et al. Survival after Resection of Multiple Tumor Foci of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2019, 23, 2239–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proskuriakova, E.; Khedr, A. Current Targeted Therapy Options in the Treatment of Cholangiocarcinoma: A Literature Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e26233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, B.M.; Hidayat, H.J.; Salihi, A.; Sabir, D.K.; Taheri, M.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. MicroRNA: A signature for cancer progression. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepanek, J.; Skorupa, M.; Tretyn, A. MicroRNA as a Potential Therapeutic Molecule in Cancer. Cells 2022, 11, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Chen, Y.; Tang, C.; Li, H.; Wang, B.; Yan, Q.; Hu, J.; Zou, S. MicroRNA-144 suppresses cholangiocarcinoma cell proliferation and invasion through targeting platelet activating factor acetylhydrolase isoform 1b. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Yin, J.J.; Cong, J.J. Downregulation of microRNA-193-3p inhibits the progression of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cells by upregulating TGFBR3. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 15, 4508–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Shi, L.; Geng, Z. MicroRNA-551b-3p inhibits tumour growth of human cholangiocarcinoma by targeting Cyclin D1. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 4945–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Jiang, J.; Fang, M.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Song, Y.; Kong, G.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, B.; et al. MicroRNA-129-2-3p directly targets Wip1 to suppress the proliferation and invasion of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 3216–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Lei, S.; Zeng, Z.; Pan, S.; Zhang, J.; Xue, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lan, J.; Xu, S.; Mao, D.; et al. MicroRNA-137 suppresses the proliferation, migration and invasion of cholangiocarcinoma cells by targeting WNT2B. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 45, 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Luo, Y.F.; Zhou, W.Y.; Liu, B.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, Y.Z.; Huang, R.; Peng, C.; He, Z.L.; Wang, J.; et al. miR-373 inhibits autophagy and further promotes apoptosis of cholangiocarcinoma cells by targeting ULK1. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chai, Z.; Sun, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, X.; Yang, L.; Zhou, X.; Liu, F. Overexpression of microRNA-96 is associated with poor prognosis and promotes proliferation, migration and invasion in cholangiocarcinoma cells via MTSS1. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 2757–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Peng, J.J.; Tan, Y.; Zou, Q.; Song, X.F.; Du, M.; Yang, Z.H.; Tan, Y.; et al. MicroRNA-1 promotes apoptosis of hepatocarcinoma cells by targeting apoptosis inhibitor-5 (API-5). FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, K.; Sakai, M.; Sugito, N.; Kumazaki, M.; Shinohara, H.; Yamada, N.; Nakayama, T.; Ueda, H.; Nakagawa, Y.; Ito, Y.; et al. PTBP1-associated microRNA-1 and -133b suppress the Warburg effect in colorectal tumors. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 18940–18952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, W.; Li, Q.; Shen, W.; Guo, H.; Zhao, S. The long non-coding RNA HOTAIR promotes thyroid cancer cell growth, invasion and migration through the miR-1-CCND2 axis. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.M.; Wu, H.L.; Yu, X.; Tang, K.; Wang, S.G.; Ye, Z.Q.; Hu, J. The putative tumour suppressor miR-1-3p modulates prostate cancer cell aggressiveness by repressing E2F5 and PFTK1. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wen, C.; Zhao, Y.; Jin, S.; Hu, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, L.; Zhang, B.; Wang, W.; et al. MicroRNA-1 inhibits tumorigenicity of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and enhances sensitivity to gefitinib. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, J.; Zuo, J.; Liang, Y.; Yuan, G. miR-1-3p suppresses the epithelial-mesenchymal transition property in renal cell cancer by downregulating Fibronectin 1. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 5573–5587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.K.; Ma, T.; Yu, Y.; Suo, Y.; Li, K.; Song, S.C.; Zhang, W. MiR-1/GOLPH3/Foxo1 Signaling Pathway Regulates Proliferation of Bladder Cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 18, 1533033819886897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Cai, N.; Zhao, L. MicroRNA-1 regulates the growth and chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells by targeting MEK/ERK pathway. J. BUON 2020, 25, 2215–2220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.J.; Li, J.Z.; Wang, L.L. MicroRNA-1-3p inhibits the growth and metastasis of ovarian cancer cells by targeting DYNLT3. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 8713–8721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Han, H.; Yang, L.; Lin, H. MiR-1-3p targets CENPF to repress tumor-relevant functions of gastric cancer cells. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, P.; Siddiqui, J.A.; Kshirsagar, P.G.; Venkata, R.C.; Maurya, S.K.; Mirzapoiazova, T.; Perumal, N.; Chaudhary, S.; Kanchan, R.K.; Fatima, M.; et al. MicroRNA-1 attenuates the growth and metastasis of small cell lung cancer through CXCR4/FOXM1/RRM2 axis. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, H.; Capalash, N. UHRF1: The key regulator of epigenetics and molecular target for cancer therapeutics. Tumour Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317692205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Q.; Xu, B.; Wang, P.; Fan, W.; Cai, Y.; Gu, X.; Meng, F. MiR-124 exerts tumor suppressive functions on the cell proliferation, motility and angiogenesis of bladder cancer by fine-tuning UHRF1. FEBS J. 2015, 282, 4376–4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Xu, Y.; Ge, M.; Gui, Z.; Yan, F. Regulation of UHRF1 by microRNA-9 modulates colorectal cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis. Cancer Sci. 2015, 106, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, Y.; Kurozumi, A.; Nohata, N.; Kojima, S.; Matsushita, R.; Yoshino, H.; Yamazaki, K.; Ishida, Y.; Ichikawa, T.; Naya, Y.; et al. The microRNA signature of patients with sunitinib failure: Regulation of UHRF1 pathways by microRNA-101 in renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 59070–59086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, R.; Yoshino, H.; Enokida, H.; Goto, Y.; Miyamoto, K.; Yonemori, M.; Inoguchi, S.; Nakagawa, M.; Seki, N. Regulation of UHRF1 by dual-strand tumor-suppressor microRNA-145 (miR-145-5p and miR-145-3p): Inhibition of bladder cancer cell aggressiveness. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 28460–28487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, H.; Zamzami, M.A.; Omran, Z.; Wu, W.; Mousli, M.; Bronner, C.; Alhosin, M. Targeting microRNA/UHRF1 pathways as a novel strategy for cancer therapy. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lin, S.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Chen, S. MiR-202 inhibits the proliferation and invasion of colorectal cancer by targeting UHRF1. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2019, 51, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, C.Y.; Xiang, W.; Liu, J.B.; Jiang, G.X.; Sun, F.; Wu, J.J.; Yang, X.L.; Xin, R.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, D.D.; et al. MiR-9-1 Suppresses Cell Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis by Targeting UHRF1 in Lung Cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 20, 15330338211041191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Wei, C.; Lin, J.; Dong, S.; Gao, D.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, B. UHRF1 is regulated by miR-124-3p and promotes cell proliferation in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 19875–19885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Benavente, C.A. Oncogenic Roles of UHRF1 in Cancer. Epigenomes 2024, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroni, L.; Pierantonelli, I.; Banales, J.M.; Benedetti, A.; Marzioni, M. The significance of genetics for cholangiocarcinoma development. Ann. Transl. Med. 2013, 1, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; House, M.G.; Guo, M.; Herman, J.G.; Clark, D.P. Promoter methylation profiles of tumor suppressor genes in intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2005, 18, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniyal, P.; Kashyap, V.K.; Behl, T.; Parashar, D.; Rawat, R. KRAS Mutations in Cancer: Understanding Signaling Pathways to Immune Regulation and the Potential of Immunotherapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shi, J.; Zhong, J.; Huang, Z.; Luo, X.; Huang, Y.; Feng, S.; Shao, J.; Liu, D. miR-1, regulated by LMP1, suppresses tumour growth and metastasis by targeting K-ras in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 96, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Xu, W.; Du, X.; Hou, J. MALAT1 silencing suppresses prostate cancer progression by upregulating miR-1 and downregulating KRAS. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 3461–3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedorova, M.S.; Snezhkina, A.V.; Lipatova, A.V.; Pavlov, V.S.; Kobelyatskaya, A.A.; Guvatova, Z.G.; Pudova, E.A.; Savvateeva, M.V.; Ishina, I.A.; Demidova, T.B.; et al. NETO2 Is Deregulated in Breast, Prostate, and Colorectal Cancer and Participates in Cellular Signaling. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 594933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Jiang, L.; He, T.; Liu, J.J.; Fan, J.Y.; Xu, X.H.; Tang, B.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, Y.L.; Qian, F.; et al. NETO2 promotes invasion and metastasis of gastric cancer cells via activation of PI3K/Akt/NF-κB/Snail axis and predicts outcome of the patients. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.C.; Chen, T.Y.; Liao, L.T.; Chen, T.; Li, Q.L.; Xu, J.X.; Hu, J.W.; Zhou, P.H.; Zhang, Y.Q. NETO2 promotes esophageal cancer progression by inducing proliferation and metastasis via PI3K/AKT and ERK pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Yamamoto, H.; Nakanishi, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Inoue, A.; Tei, M.; Hirose, H.; Uemura, M.; Nishimura, J.; Hata, T.; et al. Innovative delivery of siRNA to solid tumors by super carbonate apatite. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaal, A.M.; Sohal, I.S.; Iyer, S.G.; Sudarshan, K.; Orellana, E.A.; Ozcan, K.E.; Dos Santos, A.P.; Low, P.S.; Kasinski, A.L. Selective targeting of chemically modified miR-34a to prostate cancer using a small molecule ligand and an endosomal escape agent. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muto, M.; Ishigame, T.; Kimura, T.; Sato, N.; Kofunato, Y.; Kenjo, A.; Yamamoto, H.; Yokoyama, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Marubashi, S. MicroRNA-1 Suppresses Tumor Progression and UHRF1 Expression in Cholangiocarcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11718. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311718

Muto M, Ishigame T, Kimura T, Sato N, Kofunato Y, Kenjo A, Yamamoto H, Yokoyama Y, Yamamoto H, Marubashi S. MicroRNA-1 Suppresses Tumor Progression and UHRF1 Expression in Cholangiocarcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11718. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311718

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuto, Makoto, Teruhide Ishigame, Takashi Kimura, Naoya Sato, Yasuhide Kofunato, Akira Kenjo, Hiroyuki Yamamoto, Yuhki Yokoyama, Hirofumi Yamamoto, and Shigeru Marubashi. 2025. "MicroRNA-1 Suppresses Tumor Progression and UHRF1 Expression in Cholangiocarcinoma" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11718. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311718

APA StyleMuto, M., Ishigame, T., Kimura, T., Sato, N., Kofunato, Y., Kenjo, A., Yamamoto, H., Yokoyama, Y., Yamamoto, H., & Marubashi, S. (2025). MicroRNA-1 Suppresses Tumor Progression and UHRF1 Expression in Cholangiocarcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11718. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311718