The Cellular Effects of Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate in Non-Malignant Colonic Epithelia Involve Oxidative Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

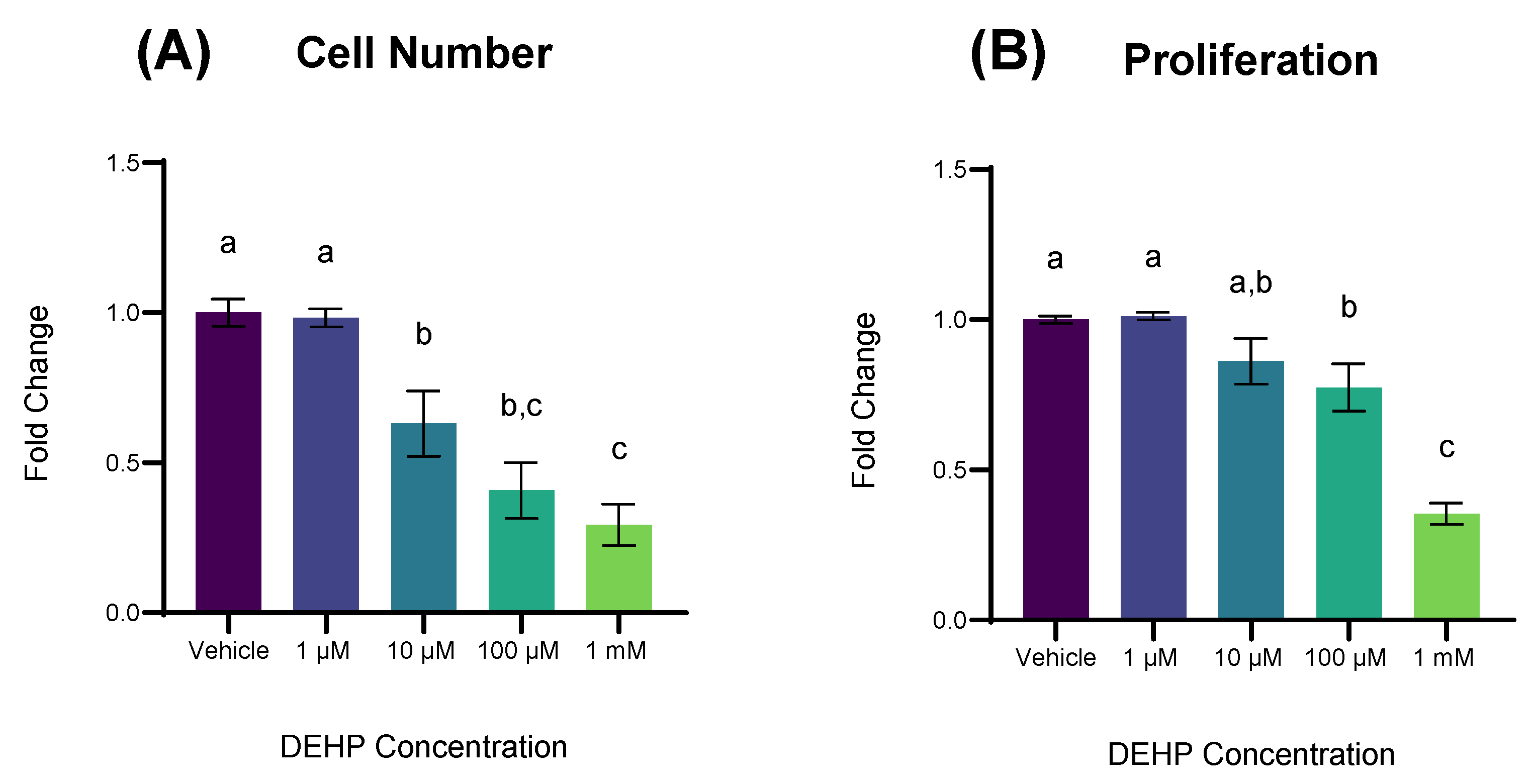

2.1. DEHP Exposure Reduces Cell Number and Cellular Proliferation in Non-Malignant Colonocytes

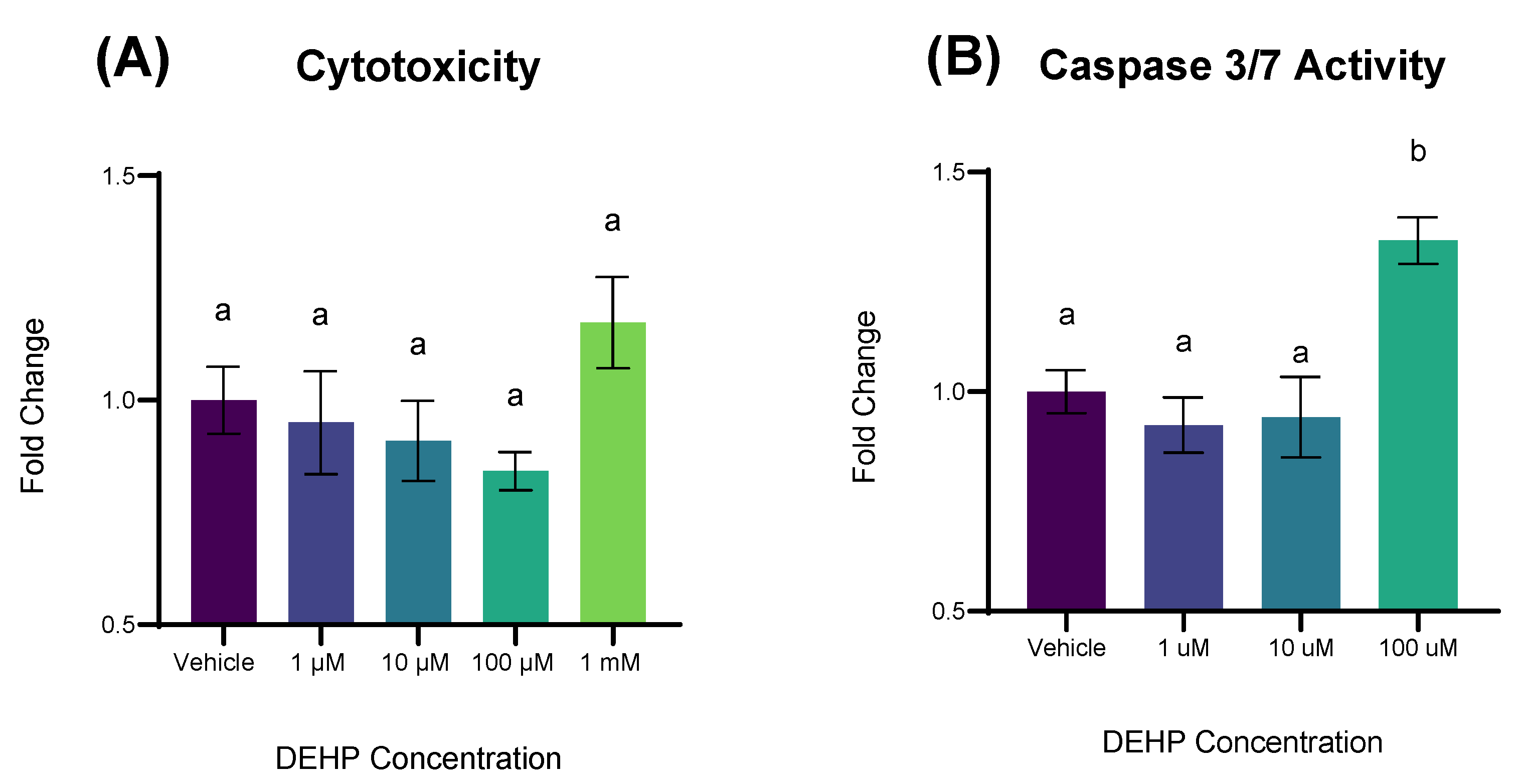

2.2. Short-Term Exposure to DEHP Results in Apoptosis but Not Cytotoxicity

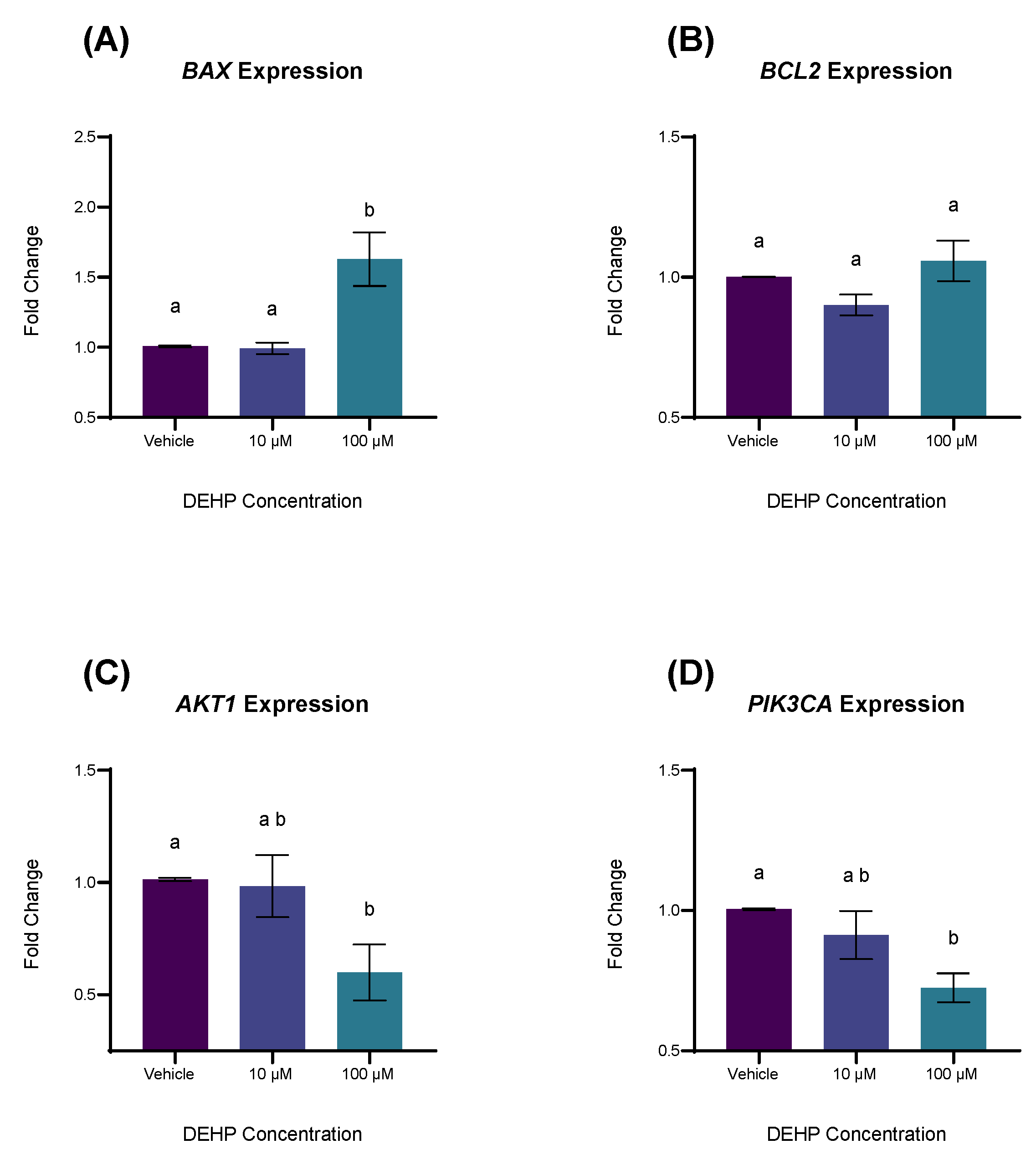

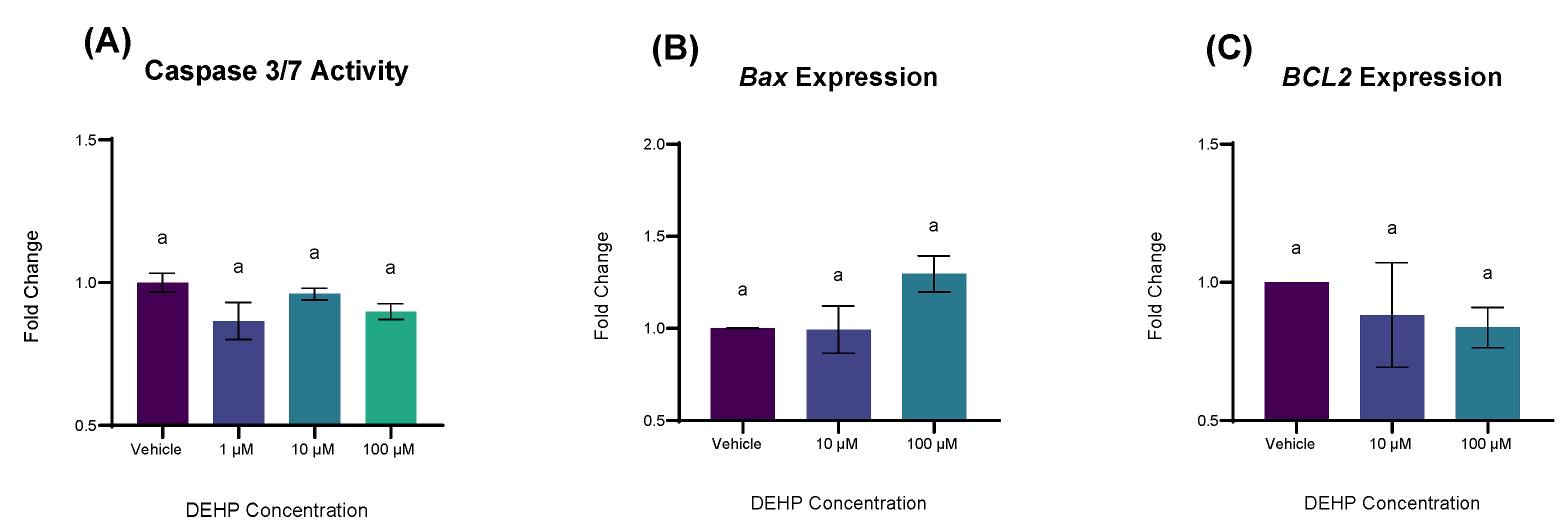

2.3. DEHP Exposure Differentially Affects the Expression of Genes Associated with Apoptosis and Cell Survival

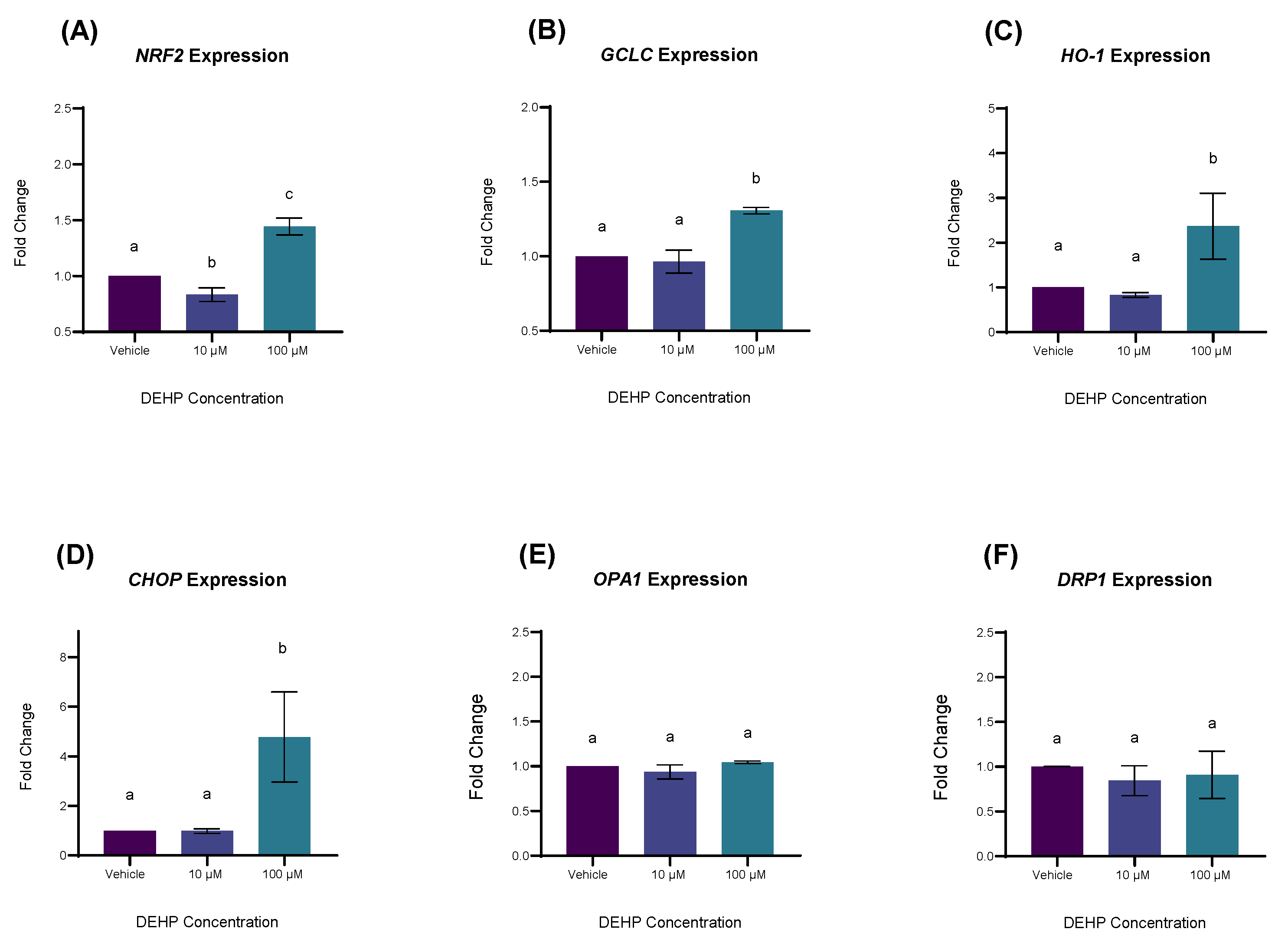

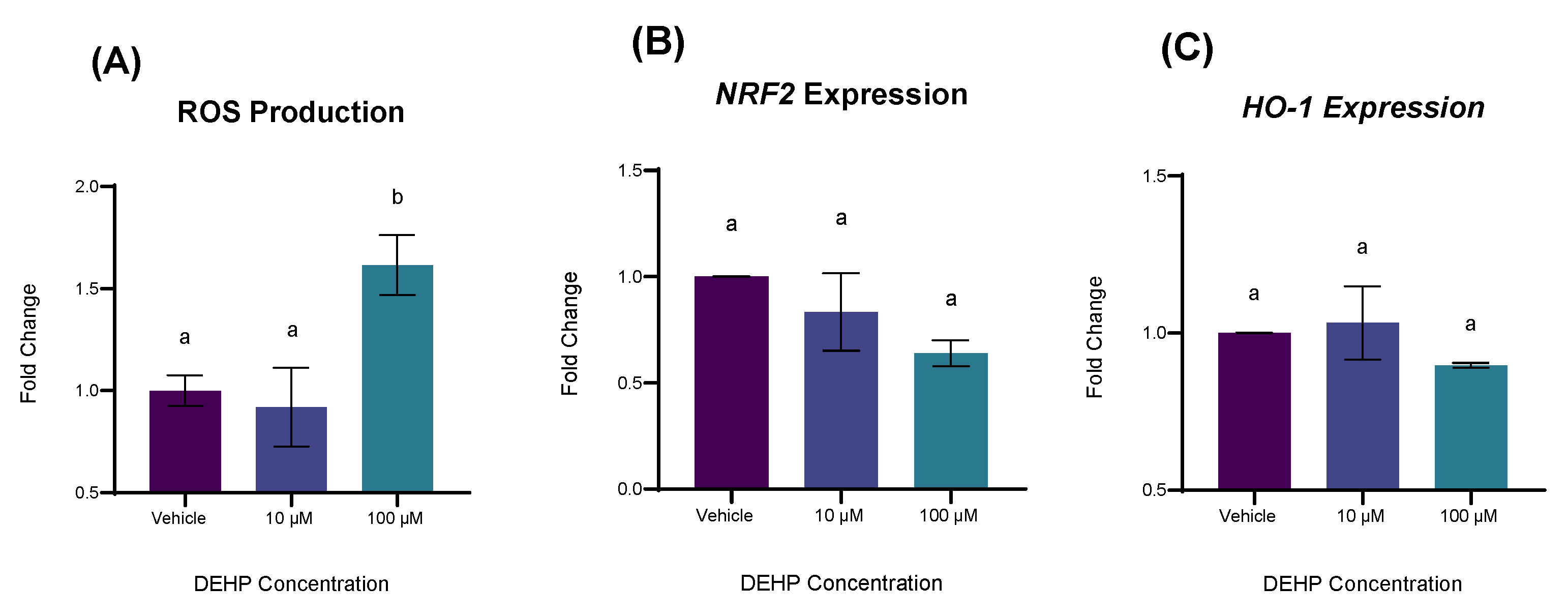

2.4. DEHP Exposure Increases the Expression of Genes Involved in Antioxidant Defense and Oxidative Stress

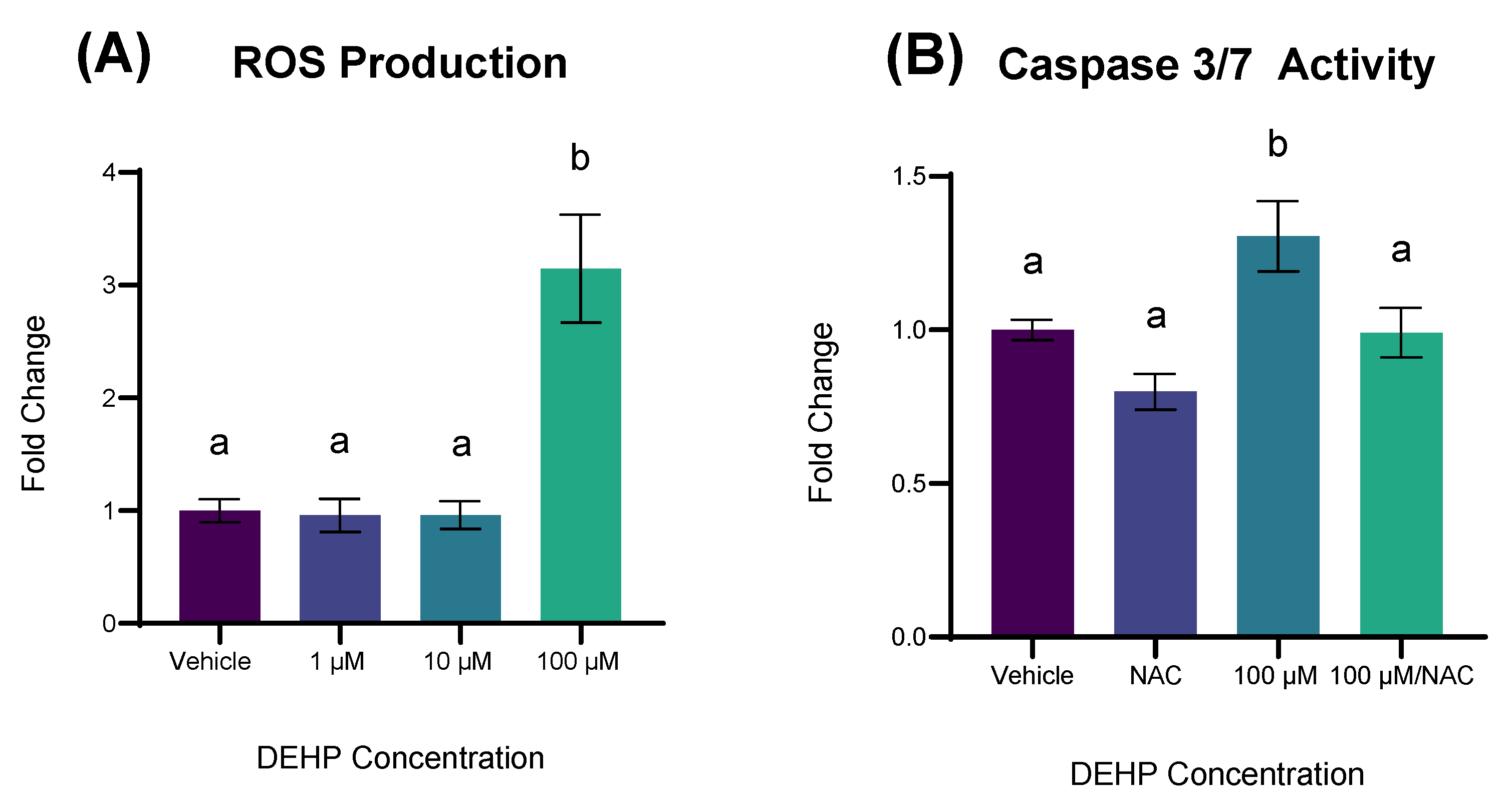

2.5. DEHP-Induced Apoptosis Is Accompanied by ROS Production and Is Attenuated by NAC Pretreatment

2.6. Knock-Out of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Disrupts Apoptotic Signaling in YAMCs Exposed to DEHP

2.7. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor, in Part, Mediates the Response to DEHP-Mediated Oxidative Stress

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Chemicals and Dose Selection

4.3. Cell Number

4.4. Proliferation

4.5. Cytotoxicity

4.6. Apoptosis

4.7. RNA Isolation

4.8. cDNA Synthesis, RT-PCR, and Primer Selection

4.9. ROS Quantification

4.10. N-Acetyl L-Cysteine Assay

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dualde, P.; León, N.; Sanchis, Y.; Corpas-Burgos, F.; Fernández, S.F.; Hernández, C.S.; Saez, G.; Pérez-Zafra, E.; Mora-Herranz, A.; Pardo, O.; et al. Biomonitoring of Phthalates, Bisphenols and Parabens in Children: Exposure, Predictors and Risk Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowdhwal, S.S.S.; Chen, J. Toxic Effects of Di-2-ethylhexyl Phthalate: An Overview. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1750368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di(2-Ethylhexyl)Phthalate (DEHP)|Toxicological Profile|ATSDR. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/ToxProfiles/ToxProfiles.aspx?id=684&tid=65 (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Miao, Y.; Wang, R.; Lu, C.; Zhao, J.; Deng, Q. Lifetime cancer risk assessment for inhalation exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa, J.M.; Kato, L.S.; Galvan, D.; Lelis, C.A.; Saraiva, T.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Occurrence of phthalates in different food matrices: A systematic review of the main sources of contamination and potential risks. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 2043–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alp, A.C.; Yerlikaya, P. Phthalate ester migration into food: Effect of packaging material and time. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, L.; McCray, N.L.; VanNoy, B.N.; Yau, A.; Geller, R.J.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Zota, A.R. Phthalate and novel plasticizer concentrations in food items from U.S. fast food chains: A preliminary analysis. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2022, 32, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Cheng, J.; Tang, Z.; He, Y.; Lyu, Y. Widespread occurrence of phthalates in popular take-out food containers from China and the implications for human exposure. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 290, 125851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Leung, A.O.W.; Chu, L.H.; Wong, M.H. Phthalates contamination in China: Status, trends and human exposure-with an emphasis on oral intake. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovsky, O.; Buerger, A.N.; Vespalcova, H.; Sohag, S.R.; Hanlon, A.T.; Ginn, P.E.; Craft, S.L.; Smatana, S.; Budinska, E.; Persico, M.; et al. Evaluation of Microbiome-Host Relationships in the Zebrafish Gastrointestinal System Reveals Adaptive Immunity Is a Target of Bis(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 5719–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaga, S.; Lee, S.; Ji, B.; Andreasson, A.; Talley, N.J.; Agréus, L.; Bidkhori, G.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Park, J.; Lee, D.; et al. Compositional and functional differences of the mucosal microbiota along the intestine of healthy individuals. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.T.; Chiu, K.; Zheng, E.; Martinez, A.; Chiu, J.; Raj, K.; Stasiak, S.; Lai, N.Z.E.; Arcanjo, R.B.; Flaws, J.A.; et al. Subchronic exposure to environmentally relevant concentrations of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate differentially affects the colon and ileum in adult female mice. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.; Seo, J.; Yeun, J.; Choi, H.; Kim, Y.-I.; Chang, S.-Y. The role of mucosal barriers in human gut health. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2021, 44, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.-M.; Kim, S. In vitro Models of the Small Intestine for Studying Intestinal Diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 767038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amara, I.; Timoumi, R.; Annabi, E.; Salem, I.B.; Abid-Essefi, S. Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate inhibits glutathione regeneration and dehydrogenases of the pentose phosphate pathway on human colon carcinoma cells. Cell Stress Chaperones 2020, 25, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-P.; Lee, Y.-K.; Huang, S.Y.; Shi, P.-C.; Hsu, P.-C.; Chang, C.-F. Phthalate exposure promotes chemotherapeutic drug resistance in colon cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 13167–13180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Bodmer, W.F. Analysis of P53 mutations and their expression in 56 colorectal cancer cell lines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, C.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Peng, Z. ROS-induced lipid peroxidation modulates cell death outcome: Mechanisms behind apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Role of Nrf2 in Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Tian, M.; Ding, C.; Yu, S. The C/EBP Homologous Protein (CHOP) Transcription Factor Functions in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Apoptosis and Microbial Infection. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, D. Mitochondrial oxidative stress causes mitochondrial fragmentation via differential modulation of mitochondrial fission–fusion proteins. FEBS J. 2011, 278, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grishanova, A.Y.; Perepechaeva, M.L. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Oxidative Stress as a Double Agent and Its Biological and Therapeutic Significance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, M.; Schrenk, D. Dioxin toxicity, aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling, and apoptosis-persistent pollutants affect programmed cell death. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2011, 41, 292–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Jin, U.-H.; Allred, C.D.; Jayaraman, A.; Chapkin, R.S.; Safe, S. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activity of Tryptophan Metabolites in Young Adult Mouse Colonocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, U.-H.; Cheng, Y.; Park, H.; Davidson, L.A.; Callaway, E.S.; Chapkin, R.S.; Jayaraman, A.; Asante, A.; Allred, C.; Weaver, E.A.; et al. Short Chain Fatty Acids Enhance Aryl Hydrocarbon (Ah) Responsiveness in Mouse Colonocytes and Caco-2 Human Colon Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, T.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Yang, P.-J.; Chiu, C.-C.; Liang, S.-S.; Ou-Yang, F.; Kan, J.-Y.; Hou, M.-F.; Wang, T.-N.; Tsai, E.-M. DEHP mediates drug resistance by directly targeting AhR in human breast cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 145, 112400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójtowicz, A.K.; Sitarz-Głownia, A.M.; Szczęsna, M.; Szychowski, K.A. The Action of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) in Mouse Cerebral Cells Involves an Impairment in Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) Signaling. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 35, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockinger, B.; Shah, K.; Wincent, E. AHR in the intestinal microenvironment: Safeguarding barrier function. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Xia, Y.; Pan, W.; Zhou, D. Antagonistic effect of nano-selenium on hepatocyte apoptosis induced by DEHP via PI3K/AKT pathway in chicken liver. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 218, 112282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Xu, T.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Gao, M.; Lin, H. Evodiamine alleviates DEHP-induced hepatocyte pyroptosis, necroptosis and immunosuppression in grass carp through ROS-regulated TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 140, 108995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.H.; Oh, Y.S.; Heo, S.-H.; Kim, K.-H.; Kim, D.Y.; Lee, S.R.; Chae, H.D. Effects of Phthalate Esters on Human Myometrial and Fibroid Cells: Cell Culture and NOD-SCID Mouse Data. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 28, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaedlich, K.; Gebauer, S.; Hunger, L.; Beier, L.-S.; Koch, H.M.; Wabitsch, M.; Fischer, B.; Ernst, J. DEHP deregulates adipokine levels and impairs fatty acid storage in human SGBS-adipocytes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Shi, X.; Xu, S. Microplastics and di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate synergistically induce apoptosis in mouse pancreas through the GRP78/CHOP/Bcl-2 pathway activated by oxidative stress. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 167, 113315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaedlich, K.; Beier, L.-S.; Kolbe, J.; Wabitsch, M.; Ernst, J. Pro-inflammatory effects of DEHP in SGBS-derived adipocytes and THP-1 macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, K.; De, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y. Typical phthalic acid esters induce apoptosis by regulating the PI3K/Akt/Bcl-2 signaling pathway in rat insulinoma cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertheloot, D.; Latz, E.; Franklin, B.S. Necroptosis, pyroptosis and apoptosis: An intricate game of cell death. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 1106–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Pandey, V.; Sahu, A.N.; Singh, A.K.; Dubey, P.K. Encircling granulosa cells protects against di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-induced apoptosis in rat oocytes cultured in vitro. Zygote 2019, 27, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Pandey, V.; Sahu, A.N.; Singh, A.; Dubey, P.K. Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) inhibits steroidogenesis and induces mitochondria-ROS mediated apoptosis in rat ovarian granulosa cells. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 8, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Yang, D.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; Wei, J.; Chen, J. Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) induces apoptosis and autophagy of mouse GC-1 spg cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2020, 35, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Li, W.; Zhu, X.; Xu, L. Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) induces apoptosis of mouse HT22 hippocampal neuronal cells via oxidative stress. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2020, 36, 844–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, A.; Foo, A.S.C.; Lam, H.Y.; Yap, K.C.H.; Jacot, W.; Jones, R.H.; Eng, H.; Nair, M.G.; Makvandi, P.; Geoerger, B.; et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuruta, F.; Masuyama, N.; Gotoh, Y. The Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K)-Akt Pathway Suppresses Bax Translocation to Mitochondria *. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 14040–14047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhang, W.; Shi, X.; Xu, S. Di-(2-ethyl hexyl) phthalate induced oxidative stress promotes microplastics mediated apoptosis and necroptosis in mice skeletal muscle by inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Toxicology 2022, 474, 153226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, X.; Qi, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, S.; Lin, H. Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate and Microplastics Induced Neuronal Apoptosis through the PI3K/AKT Pathway and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 10771–10781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohiti, S.; Alizadeh, E.; Bisgaard, L.S.; Ebrahimi-Mameghani, M.; Christoffersen, C. The AhR/P38 MAPK pathway mediates kynurenine-induced cardiomyocyte damage: The dual role of resveratrol in apoptosis and autophagy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 186, 118015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Traore, K.; Li, W.; Amri, H.; Huang, H.; Wu, C.; Chen, H.; Zirkin, B.; Papadopoulos, V. Molecular Mechanisms Mediating the Effect of Mono-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate on Hormone-Stimulated Steroidogenesis in MA-10 Mouse Tumor Leydig Cells. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 3348–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, A.M.; Inman, Z.; Mourikes, V.E.; Santacruz-Márquez, R.; Gonsioroski, A.; Laws, M.J.; Flaws, J.A. The role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in mediating the effects of mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in mouse ovarian antral follicles. Biol. Reprod. 2023, 110, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenda, A.; Rousseau, S. p38 MAP-Kinases pathway regulation, function and role in human diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2007, 1773, 1358–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Cheong, Y.-K.; Kim, N.-H.; Chung, H.-T.; Kang, D.G.; Pae, H.-O. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases and Reactive Oxygen Species: How Can ROS Activate MAPK Pathways? J. Signal Transduct. 2011, 2011, 792639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esakky, P.; Hansen, D.A.; Drury, A.M.; Moley, K.H. Cigarette smoke-induced cell cycle arrest in spermatocytes [GC-2spd(ts)] is mediated through crosstalk between Ahr–Nrf2 pathway and MAPK signaling. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 7, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.-X.; Yuan, S.-X.; Ren, C.-M.; Yu, Y.; Sun, W.-J.; He, B.-C.; Wu, K. Oridonin upregulates PTEN through activating p38 MAPK and inhibits proliferation in human colon cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 3341–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muranen, T.; Selfors, L.M.; Hwang, J.; Gallegos, L.L.; Coloff, J.L.; Thoreen, C.C.; Kang, S.A.; Sabatini, D.M.; Mills, G.B.; Brugge, J.S. ERK and p38 MAPK activities determine sensitivity to PI3K/mTOR inhibition via regulation of MYC and YAP. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 7168–7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Mitra, S.; Crowe, S.E. Oxidative Stress: An Essential Factor in the Pathogenesis of Gastrointestinal Mucosal Diseases. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 329–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vona, R.; Pallotta, L.; Cappelletti, M.; Severi, C.; Matarrese, P. The Impact of Oxidative Stress in Human Pathology: Focus on Gastrointestinal Disorders. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, M.; Swierczynski, M.; Fichna, J.; Piechota-Polanczyk, A. The Nrf2 in the pathophysiology of the intestine: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications for inflammatory bowel diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 163, 105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amara, I.; Ontario, M.L.; Scuto, M.; Lo Dico, G.M.; Sciuto, S.; Greco, V.; Abid-Essefi, S.; Signorile, A.; Salinaro, A.T.; Calabrese, V. Moringa oleifera Protects SH-SY5YCells from DEHP-Induced Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Apoptosis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verfaillie, T.; Rubio, N.; Garg, A.D.; Bultynck, G.; Rizzuto, R.; Decuypere, J.-P.; Piette, J.; Linehan, C.; Gupta, S.; Samali, A.; et al. PERK is required at the ER-mitochondrial contact sites to convey apoptosis after ROS-based ER stress. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 1880–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, B.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Velkov, T.; Tang, S.; Shen, J.; Dai, C. Colistin Induces Oxidative Stress and Apoptotic Cell Death through the Activation of the AhR/CYP1A1 Pathway in PC12 Cells. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, W.; Hu, L.; Scrivens, P.J.; Batist, G. Transcriptional Regulation of NF-E2 p45-related Factor (NRF2) Expression by the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor-Xenobiotic Response Element Signaling Pathway: DIRECT CROSS-TALK BETWEEN PHASE I AND II DRUG-METABOLIZING ENZYMES *. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 20340–20348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, J.; Das, J.; Manna, P.; Sil, P.C. Hepatotoxicity of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate is attributed to calcium aggravation, ROS-mediated mitochondrial depolarization, and ERK/NF-κB pathway activation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1779–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zhang, W.; Gao, M.; Lin, H. Mechanism of evodiamine blocking Nrf2/MAPK pathway to inhibit apoptosis of grass carp hepatocytes induced by DEHP. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 263, 109506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Heping, H.; Shen, Y.; Jin, S.; Li, D.; Zhang, A.; Ren, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; et al. AMPK/p38/Nrf2 activation as a protective feedback to restrain oxidative stress and inflammation in microglia stimulated with sodium fluoride. Chemosphere 2020, 244, 125495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weige, C.C.; Allred, K.F.; Allred, C.D. Estradiol Alters Cell Growth in Nonmalignant Colonocytes and Reduces the Formation of Preneoplastic Lesions in the Colon. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 9118–9124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, R.H.; Robinson, P.S. Establishment of conditionally immortalized epithelial cell lines from the intestinal tissue of adult normal and transgenic mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009, 296, G455–G460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, P.-H.; Chang, Y.-Z.; Chang, H.-P.; Wang, S.-L.; Haung, H.-I.; Huang, P.-C.; Chen, J.-Y. Exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in premature neonates in a neonatal intensive care unit in Taiwan. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 13, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subotic, U.; Hannmann, T.; Kiss, M.; Brade, J.; Breitkopf, K.; Loff, S. Extraction of the Plasticizers Diethylhexylphthalate and Polyadipate from Polyvinylchloride Nasogastric Tubes Through Gastric Juice and Feeding Solution. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2007, 44, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelliez, A.; Décaudin, B.; Lecoeur, M. Impact of the pathogen inactivation process on the migration of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate from plasma bags. Vox Sang. 2022, 117, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| BAX | AATATGGAGCTGCAGAGGATG | CCAGTTGAAGTTGCCATCAGC |

| BCL2 | GCTGGGGATGACTTCTCTCG | CCACAATCCTCCCCCAGTTC |

| AKT1 | CTCATTCCAGACCCACGACC | TAGGAGAACTTGATCAGGCGG |

| PIK3CA | CACGACCATCTTCGGGTGAA | TCACGGTTGCCTACTGGTTC |

| NRF2 | CTTTAGTCAGCGACAGAAGGAC | AGGCATCTTGTTTGGGAATGTG |

| HO-1 | ATGTTGACTGACCACGAC | GCCCCACTTTGTTAGGAAA |

| GCLC | GGCCACTATCTGCCCAATTG | CTCCCCAGCGACAATCAATG |

| CHOP | TCTGTCTCTCCGGAAGTGTA | CTGGTCTACCCTCAGTCCTC |

| DRP1 | TGCAGGACGTCTTCAACACA | GACCACACCAGTTCCTCTGG |

| OPA1 | ATTGTCGGAGCAGGAATCGG | AGGATTGGCAGACTTCACAGG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bomstein, Z.S.; Allred, K.F.; Allred, C.D. The Cellular Effects of Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate in Non-Malignant Colonic Epithelia Involve Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311716

Bomstein ZS, Allred KF, Allred CD. The Cellular Effects of Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate in Non-Malignant Colonic Epithelia Involve Oxidative Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311716

Chicago/Turabian StyleBomstein, Zachary S., Kimberly F. Allred, and Clinton D. Allred. 2025. "The Cellular Effects of Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate in Non-Malignant Colonic Epithelia Involve Oxidative Stress" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311716

APA StyleBomstein, Z. S., Allred, K. F., & Allred, C. D. (2025). The Cellular Effects of Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate in Non-Malignant Colonic Epithelia Involve Oxidative Stress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11716. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311716