Lactobacillus murinus Induces CYP1A1 Expression and Modulates TNF-Alpha-Induced Responses in a Human Intestinal Epithelial Cell Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

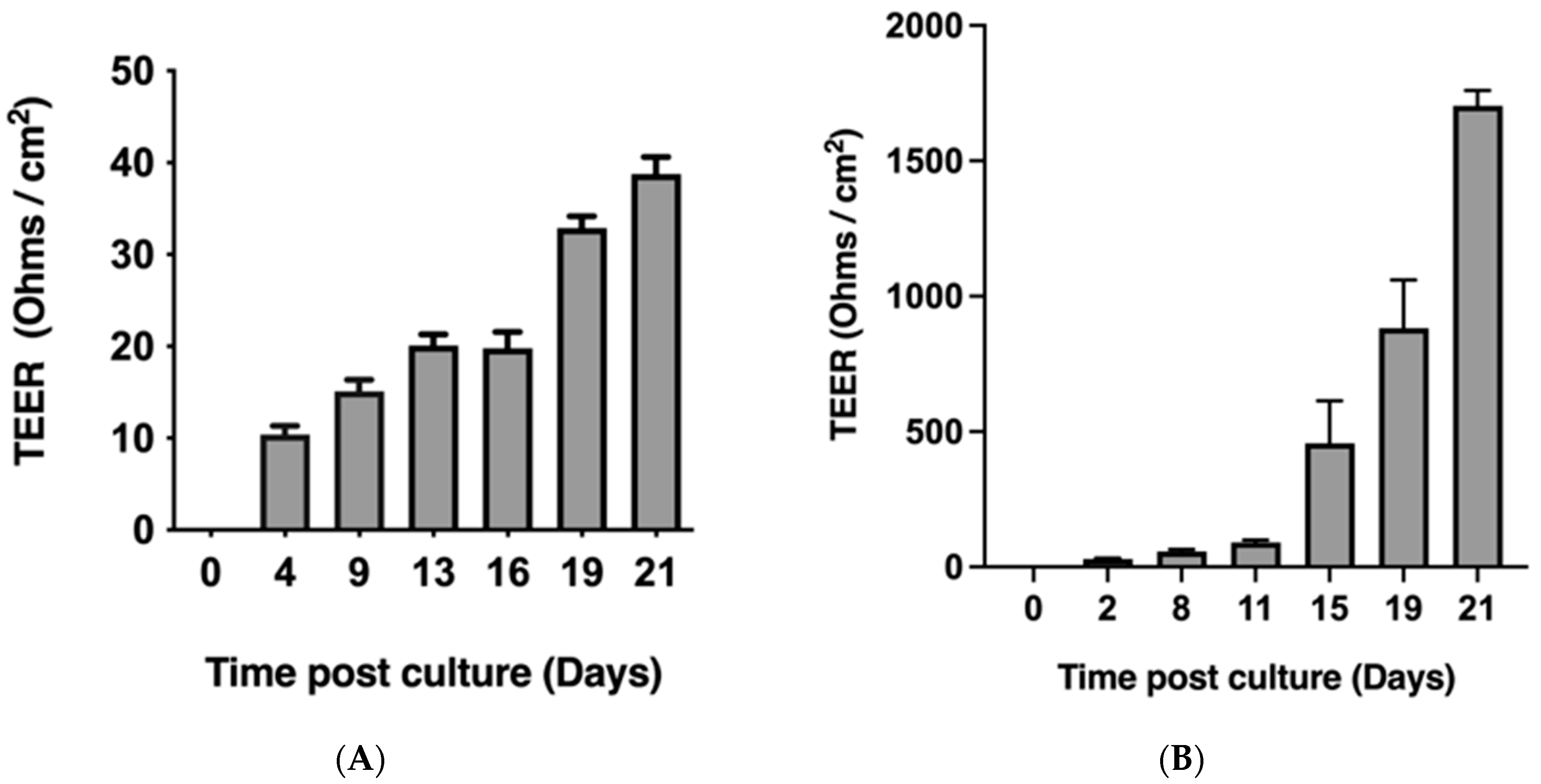

2.1. Caco-2 Monolayers Form Robust Tight Junctions When Cultured on Transwell Inserts

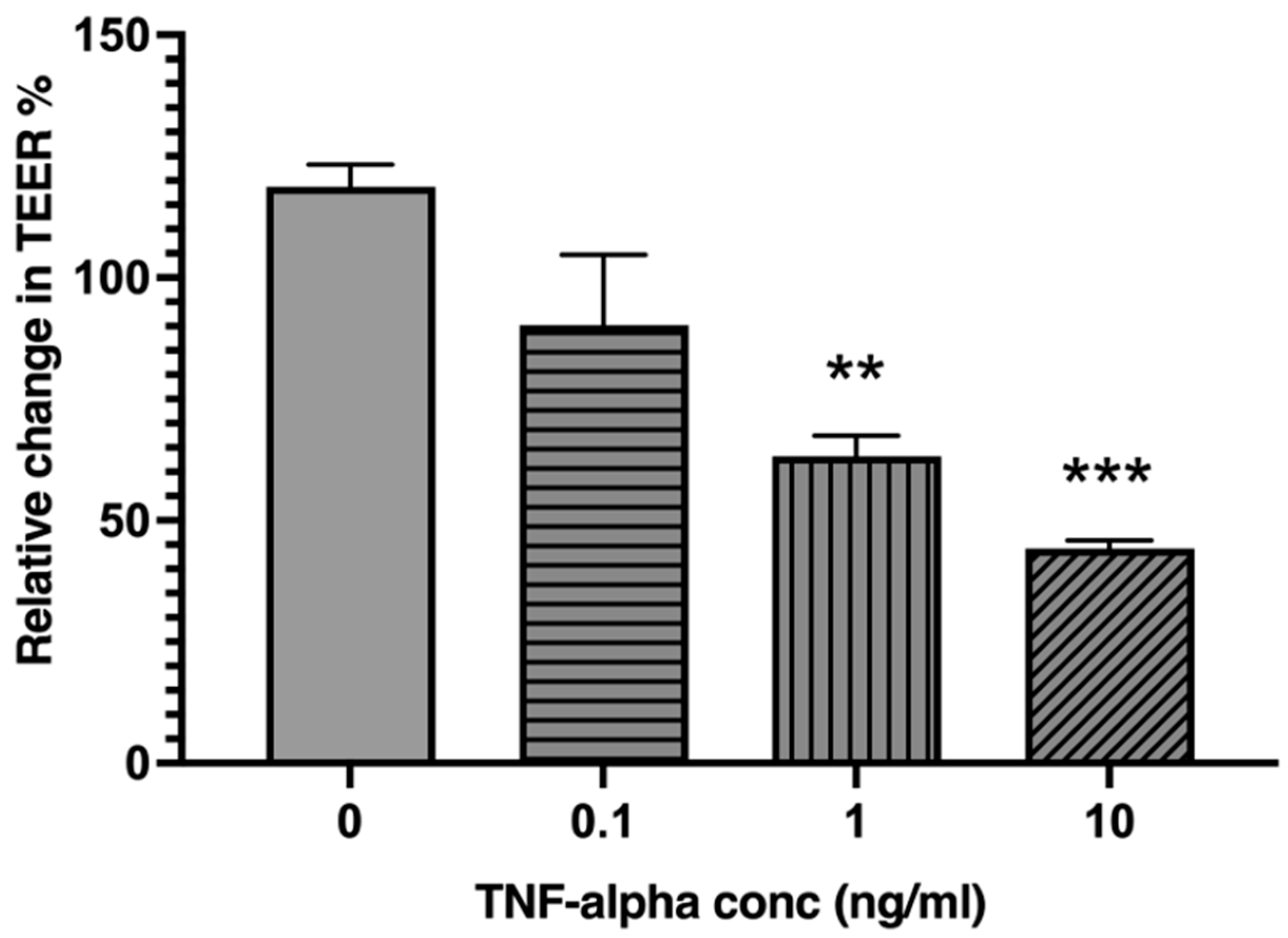

2.2. TNF-α Reduces Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Integrity in a Concentration-Dependent Manner

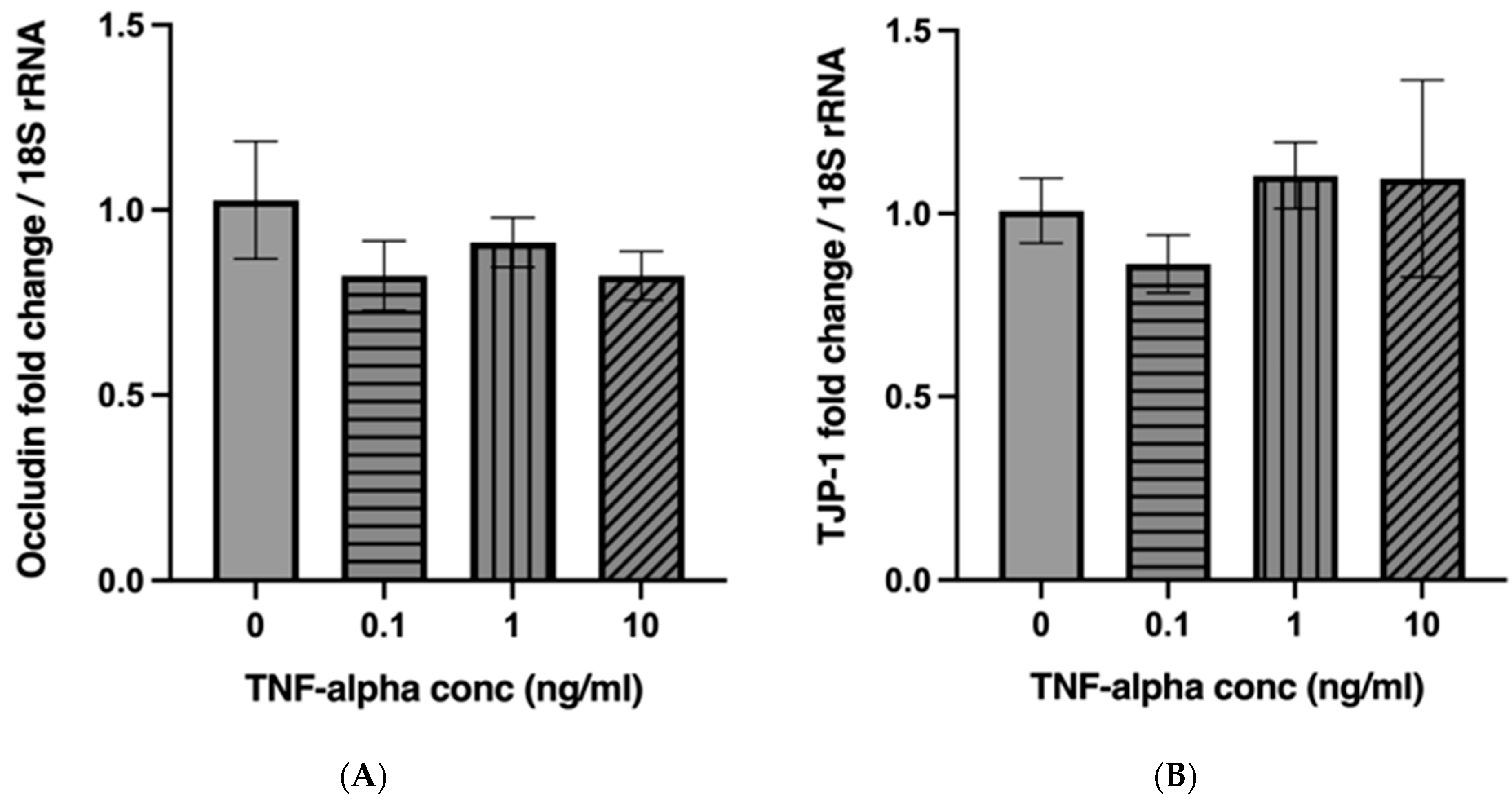

2.3. TNF-α Does Not Alter the mRNA Expression of Occludin and Tight Junction Protein 1 (TJP-1) in a Concentration-Dependent Manner

2.4. TNF-α Induces IL-8 Secretion from Intestinal Epithelial Cells in a Concentration-Dependent Manner

2.5. TCDD and FICZ Increase CYP1A1 Transcription in a Concentration-Dependent Manner

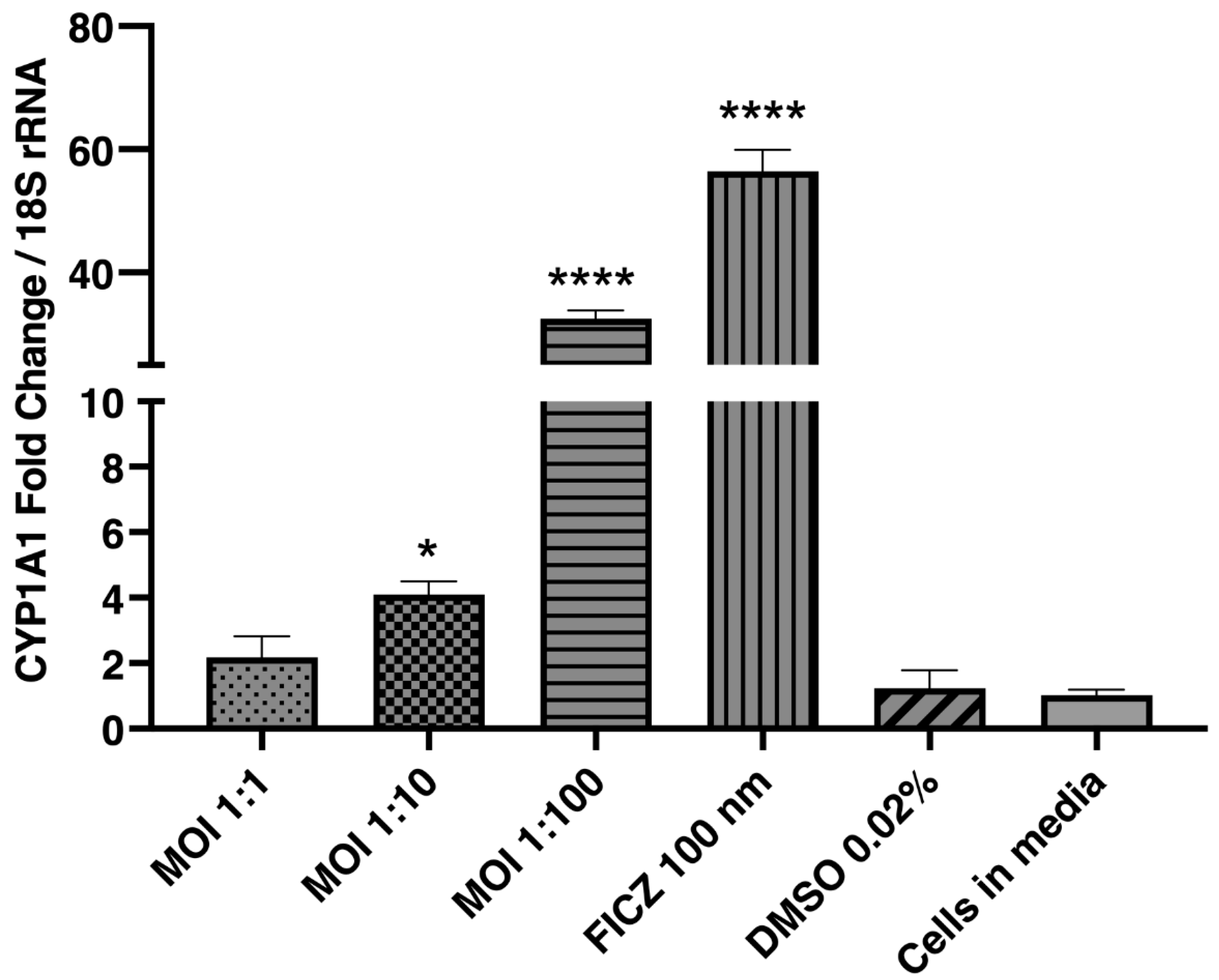

2.6. Lactobacillus murinus Modulates the CYP1A1 Transcription in Multiplicity of Infection (MOI)-Dependent Manner

2.7. AHR Associated Signaling Attenuated TNF-α-Induced Gut Barrier Disruption and Pro-Inflammatory Response in Caco-2 Monolayers

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Bacterial Culture

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Cell Treatments

4.5. Measurement of TEER

4.6. Quantification of IL-8 Protein by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.7. Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marlicz, W.; Skonieczna-Żydecka, K.; Dabos, K.J.; Łoniewski, I.; Koulaouzidis, A. Emerging concepts in non-invasive monitoring of Crohn’s disease. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 1756284818769076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Z.; Li, Y.-Y. Inflammatory bowel disease: Pathogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2014, 20, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Manne, S.; Treem, W.R.; Bennett, D. Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Pediatric and Adult Populations: Recent Estimates From Large National Databases in the United States, 2007–2016. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 26, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhoury, M.; Negrulj, R.; Mooranian, A.; Al-Salami, H. Inflammatory bowel disease: Clinical aspects and treatments. J. Inflamm. Res. 2014, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pithadia, A.B.; Jain, S. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Pharmacol. Rep. 2011, 63, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, S.; Punchard, N.; Teare, J.; Thompson, R. The mode of action of the aminosalicylates in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1993, 7, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stasi, R.; Amadori, S.; Newland, A.C.; Provan, D. Infliximab chimeric antitumor necrosis factor-α monoclonal antibody as potential treatment for myelodysplastic syndromes. Leuk. Lymphoma 2005, 46, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Kaitha, S.; Mahmood, S.; Ftesi, A.; Stone, J.; Bronze, M.S. Clinical use of anti-TNF therapy and increased risk of infections. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2013, 5, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, Y.; Bonen, D.K.; Inohara, N.; Nicolae, D.L.; Chen, F.F.; Ramos, R.; Britton, H.; Moran, T.; Karaliuskas, R.; Duerr, R.H.; et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Nature 2001, 411, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manichanh, C.; Rigottier-Gois, L.; Bonnaud, E.; Gloux, K.; Pelletier, E.; Frangeul, L.; Nalin, R.; Jarrin, C.; Chardon, P.; Marteau, P. Reduced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn’s disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut 2006, 55, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, S.; Musfeldt, M.; Wenderoth, D.; Hampe, J.; Brant, O.; Fölsch, U.; Timmis, K.; Schreiber, S. Reduction in diversity of the colonic mucosa associated bacterial microflora in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2004, 53, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Luo, X.; Yu, Z.; Mani, S.; Wang, Z.; Dou, W. Inflammatory bowel disease: A potential result from the collusion between gut microbiota and mucosal immune system. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Midha, V.; Makharia, G.K.; Ahuja, V.; Singal, D.; Goswami, P.; Tandon, R.K. The probiotic preparation, VSL#3 induces remission in patients with mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 7, 1202–1209.e1. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Wang, Q.; Ma, Y.; Li, L.; Yu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Xiao, W.; Xu, P.; et al. Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activation Modulates Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Function by Maintaining Tight Junction Integrity. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Vazquez, C.; Quintana, F.J. Regulation of the Immune Response by the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Immunity 2018, 48, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, F.J. LeA (H) Rning self-control. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 1155–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezrich, J.D.; Fechner, J.H.; Zhang, X.; Johnson, B.P.; Burlingham, W.J.; Bradfield, C.A. An interaction between kynurenine and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor can generate regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 3190–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadi, R.; Guo, S.; Ye, D.; Ma, T.Y. TNF-α modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier is regulated by ERK1/2 activation of Elk-1. Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 183 (Suppl. S1), 1871–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Peng, J.; Deng, X.-L.; Yang, L.-F.; Camara, A.D.; Omran, A.; Wang, G.-L.; Wu, L.-W.; Zhang, C.-L.; Yin, F. Mechanisms of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced leaks in intestine epithelial barrier. Cytokine 2012, 59, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mínguez, A.; Ripoll, P.; Argumánez, V.; Navarrete, I.; Aguerri, A.; Garrido, A.; Aguas, M.; Iborra, M.; Cerrillo, E.; Bastida, G.; et al. P0937 Role of Interleukin-8 in Predicting Long-Term Response to Vedolizumab in Ulcerative Colitis Patients. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2025, 19, i1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Hu, S.-W.; Chang, T.-H. Correlation between Gene Expression of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR), Hydrocarbon Receptor Nuclear Translocator (Arnt), Cytochromes P4501A1 (CYP1A1) and 1B1 (CYP1B1), and Inducibility of CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 in Human Lymphocytes. Toxicol. Sci. 2003, 71, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mescher, M.; Haarmann-Stemmann, T. Modulation of CYP1A1 metabolism: From adverse health effects to chemoprevention and therapeutic options. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 187, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.P., Jr. Induction of cytochrome P4501A1. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999, 39, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, I.J.; Raub, T.J.; Borchardt, R.T. Characterization of the human colon carcinoma cell line (Caco-2) as a model system for intestinal epithelial permeability. Gastroenterology 1989, 96, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, I.; Stenberg, P.; Artursson, P.; Kissel, T. Transport of lipophilic drug molecules in a new mucus-secreting cell culture model based on HT29-MTX cells. Pharm. Res. 2001, 18, 1138–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffarian, R.; Muro, S. Models and methods to evaluate transport of drug delivery systems across cellular barriers. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 80, e50638. [Google Scholar]

- Bohonowych, J.E.; Denison, M.S. Persistent binding of ligands to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 98, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wincent, E.; Bengtsson, J.; Bardbori, A.M.; Alsberg, T.; Luecke, S.; Rannug, U.; Rannug, A. Inhibition of cytochrome P4501-dependent clearance of the endogenous agonist FICZ as a mechanism for activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 4479–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Sorrentino, C.; Denison, M.S.; Kolaja, K.; Fielden, M.R. Induction of cyp1a1 is a nonspecific biomarker of aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation: Results of large scale screening of pharmaceuticals and toxicants in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007, 71, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, I.; Hosaka, M.; Haga, A.; Tsuji, N.; Nagata, Y.; Okada, H.; Fukuda, K.; Kakizaki, Y.; Okamoto, T.; Grave, E. The regulation mechanisms of AhR by molecular chaperone complex. J. Biochem. 2018, 163, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metidji, A.; Omenetti, S.; Crotta, S.; Li, Y.; Nye, E.; Ross, E.; Li, V.; Maradana, M.R.; Schiering, C.; Stockinger, B. The environmental sensor AHR protects from inflammatory damage by maintaining intestinal stem cell homeostasis and barrier integrity. Immunity 2018, 49, 353–362.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrlich, A.K.; Pennington, J.M.; Bisson, W.H.; Kolluri, S.K.; Kerkvliet, N.I. TCDD, FICZ, and Other High Affinity AhR Ligands Dose-Dependently Determine the Fate of CD4+ T Cell Differentiation. Toxicol. Sci. 2018, 161, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockinger, B.; Shah, K.; Wincent, E. AHR in the intestinal microenvironment: Safeguarding barrier function. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, W.; Tohyama, C. Mechanisms of Developmental Toxicity of Dioxins and Related Compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Chang, X.; Puga, A.; Xia, Y. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) by aromatic hydrocarbons: Role in the regulation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) function. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002, 64, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulero-Navarro, S.; Fernandez-Salguero, P.M. New Trends in Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Biology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 4, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockinger, B.; Meglio, P.D.; Gialitakis, M.; Duarte, J.H. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor: Multitasking in the Immune System. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 403–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, K.; Langner, E.; Makuch-Kocka, A.; Szelest, M.; Szalast, K.; Marciniak, S.; Plech, T. Effect of Tryptophan-Derived AhR Ligands, Kynurenine, Kynurenic Acid and FICZ, on Proliferation, Cell Cycle Regulation and Cell Death of Melanoma Cells-In Vitro Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannug, A.; Rannug, U. The tryptophan derivative 6-formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole, FICZ, a dynamic mediator of endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling, balances cell growth and differentiation. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2018, 48, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-H.; Henry, E.C.; Kim, D.-K.; Kim, Y.-H.; Shin, K.J.; Han, M.S.; Lee, T.G.; Kang, J.-K.; Gasiewicz, T.A.; Ryu, S.H. Novel compound 2-methyl-2H-pyrazole-3-carboxylic acid (2-methyl-4-o-tolylazo-phenyl)-amide (CH-223191) prevents 2, 3, 7, 8-TCDD-induced toxicity by antagonizing the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; DeGroot, D.E.; Hayashi, A.; He, G.; Denison, M.S. CH223191 Is a Ligand-Selective Antagonist of the Ah (Dioxin) Receptor. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 117, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudvig, J.M.; Cluett, M.M.; Gensterblum-Miller, E.U.; Chen, J.; Bell, J.A.; Mansfield, L.S. Th1/Th17-mediated Immunity and Protection from Peripheral Neuropathy in Wildtype and IL10−/− BALB/c Mice Infected with a Guillain–Barré Syndrome-associated Campylobacter jejuni Strain. Comp. Med. 2022, 72, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudvig, J.M. Interplay of Host and Pathogen Factors Determines Immunity and Clinical Outcome Following Campylobacter jejuni Infection in Mice. In Comparative Medicine and Integrative Biology; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, B.; Kolli, A.R.; Esch, M.B.; Abaci, H.E.; Shuler, M.L.; Hickman, J.J. TEER measurement techniques for in vitro barrier model systems. J. Lab. Autom. 2015, 20, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amidon, G.L.; Lee, P.I.; Topp, E.M. Transport Processes in Pharmaceutical Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, H.; Sher, A.A.; Bell, J.A.; Mansfield, L.S. Lactobacillus murinus Induces CYP1A1 Expression and Modulates TNF-Alpha-Induced Responses in a Human Intestinal Epithelial Cell Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311670

Ahmed H, Sher AA, Bell JA, Mansfield LS. Lactobacillus murinus Induces CYP1A1 Expression and Modulates TNF-Alpha-Induced Responses in a Human Intestinal Epithelial Cell Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311670

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Husnain, Azam A. Sher, Julia A. Bell, and Linda S. Mansfield. 2025. "Lactobacillus murinus Induces CYP1A1 Expression and Modulates TNF-Alpha-Induced Responses in a Human Intestinal Epithelial Cell Model" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311670

APA StyleAhmed, H., Sher, A. A., Bell, J. A., & Mansfield, L. S. (2025). Lactobacillus murinus Induces CYP1A1 Expression and Modulates TNF-Alpha-Induced Responses in a Human Intestinal Epithelial Cell Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11670. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311670