Immune-Guided Bone Healing: The Role of Osteoimmunity in Tissue Engineering Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Bone Remodeling and Osteoimmunity

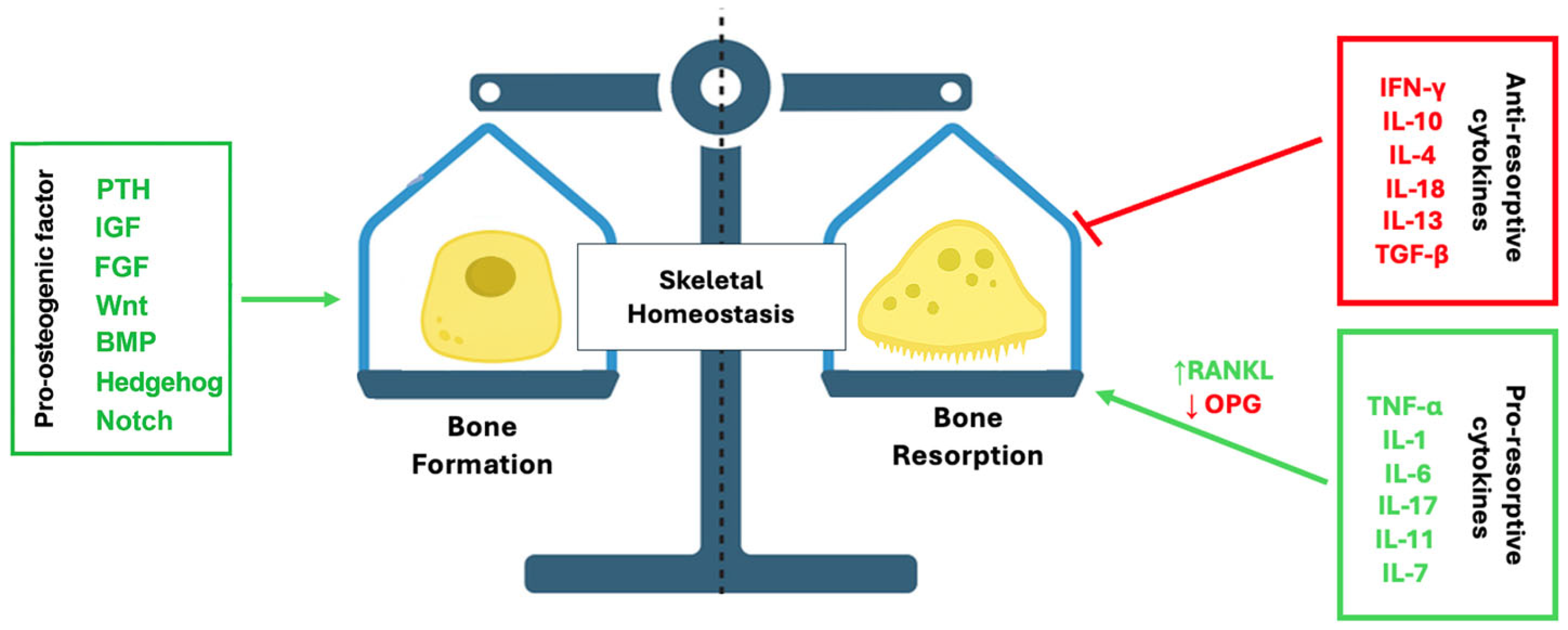

2.1. Overview of Bone Remodeling

2.2. Bone–Immune Interactions

2.3. Bone Composition and Cellular Organization

2.4. Bone Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Implications

3. The Immune System and Its Role in Bone Biology

3.1. Immune Cell Types and Signaling Pathways

3.2. Regulation of Osteoclastogenesis: Systemic and Local Signals

3.3. The RANK/RANKL/OPG Axis

4. Osteoimmunology: Bridging Bone and Immunity

4.1. Shared Origins of Osteoclasts and Immune Cells

4.2. Cytokines, Chemokines, and Growth Factors in Bone–Immune Crosstalk

5. Pathological Implications of Osteoimmune Dysregulation

5.1. Skeletal Diseases and Immune-Mediated Bone Loss

5.2. Systemic Conditions Affecting Skeletal Homeostasis

6. Immunomodulation in Bone Regeneration

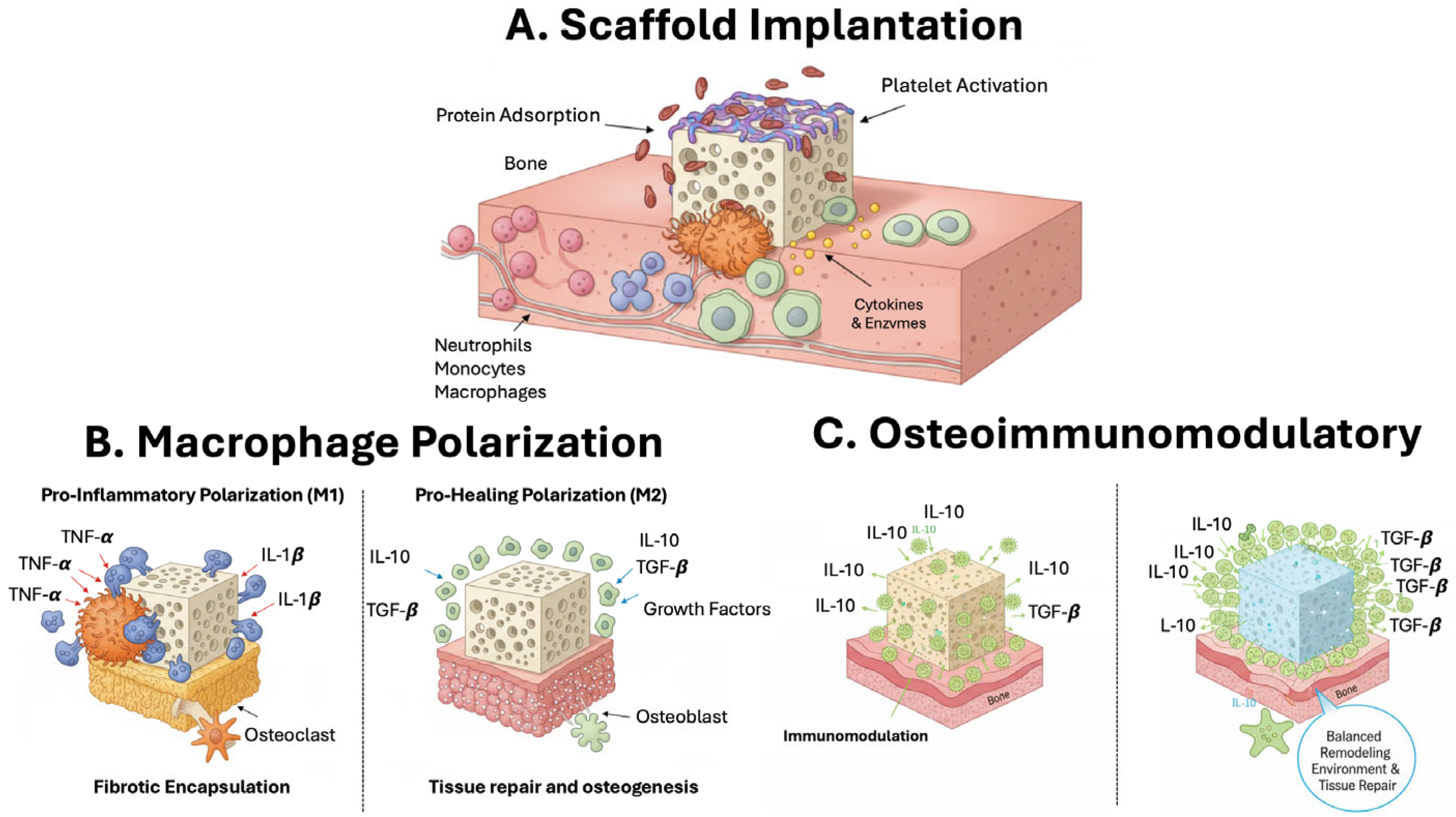

6.1. Bone Scaffolds for Immunomodulation

6.2. Scaffold-Based Strategies for Local Immune Modulation

6.3. Hydrogel Systems and Advanced Delivery Platforms

7. Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTE | Bone Tissue Engineering |

| BMSCs | Bone marrow stromal cells |

| HSCs | Hematopoietic stem cells |

| BMUs | Basic multicellular units |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| IFN-β | Interferon-beta |

| IFN- | Interferon-gamma |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| IL-12 | Interleukin-12 |

| IL-18 | Interleukin-18 |

| NK | Natural killer |

| PRRs | Pattern recognition receptors |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| NLRs | NOD-like receptors |

| RLRs | RIG-I-like receptors |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| DAMPs | Danger-associated molecular patterns |

| IL-17 | Interleukin-17 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-13 | Interleukin-13 |

| PTHrP | Parathyroid hormone-related peptide |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| RANKL | Receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand |

| M-CSF | Macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| PTH | Parathyroid hormone |

| IL-11 | Interleukin-11 |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| HSPCs | Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells |

| NHO | Neurogenic heterotopic |

| OIM | Osteoimmunomodulatory |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stem cells |

References

- Okamoto, K. Crosstalk between bone and the immune system. J. Bone Min. Metab. 2024, 42, 470–480, Erratum in J. Bone Min. Metab. 2024, 42, 481–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zhang, G.; Wu, Y.; Xiong, Y. Inflammasome Complexes: Crucial mediators in osteoimmunology and bone diseases. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 110, 109072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrzyniak, A.; Balawender, K. Structural and Metabolic Changes in Bone. Animals 2022, 12, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, D. Structural organization of the bone marrow and its role in hematopoiesis. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2021, 28, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrero, S.G.; Llamas-Sillero, P.; Serrano-López, J. A Multidisciplinary Journey towards Bone Tissue Engineering. Materials 2021, 14, 4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, B.F. Advances in osteoclast biology reveal potential new drug targets and new roles for osteoclasts. J. Bone Min. Res. 2013, 28, 711–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Liu, Y. The Role of the Immune Microenvironment in Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 3697–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, M.; Rajasingh, S.; Madasamy, P.; Rajasingh, J. Immunomodulatory and Regenerative Functions of MSC-Derived Exosomes in Bone Repair. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayanagi, H. Osteoimmunology: Shared mechanisms and crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K.; Nakashima, T.; Shinohara, M.; Negishi-Koga, T.; Komatsu, N.; Terashima, A.; Sawa, S.; Nitta, T.; Takayanagi, H. Osteoimmunology: The conceptual framework unifying the immune and skeletal systems. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 1295–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, K.A.; Li, J.; Schwarz, E.M. The emerging field of osteoimmunology. Immunol. Res. 2009, 45, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, L.; Chen, H.; Zhao, X.; Han, Q.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, B.; et al. Advances in the application and research of biomaterials in promoting bone repair and regeneration through immune modulation. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 30, 101410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zeng, X.; Deng, X.; Yang, F.; Ma, X.; Gao, W. Smart biomaterials: As active immune modulators to shape pro-regenerative microenvironments. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1669399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, G.; Petralia, S.; Fabbi, C.; Forte, S.; Franco, D.; Guglielmino, S.; Esposito, E.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Traina, F.; Conoci, S. Au, Pd and maghemite nanofunctionalized hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone regeneration. Regen. Biomater. 2020, 7, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, N.; Calabrese, G.; Sciortino, A.; Rizzo, M.G.; Messina, F.; Giammona, G.; Cavallaro, G. Microporous Fluorescent Poly(D,L-lactide) Acid-Carbon Nanodot Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials 2024, 17, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munaò, S.; D’Amora, U.; Bauso, L.V.; Ronca, A.; Manini, P.; Pezzella, A.; Raucci, M.G.; Ambrosio, L.; Calabrese, G. In Vitro Osteogenic Stimulation of Human Adipose-Derived MSCs on Biofunctional 3D-Printed Scaffolds. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, B.; Xiong, Y.; Zha, K.; Cao, F.; Zhou, W.; Abbaszadeh, S.; Ouyang, L.; Liao, Y.; Hu, W.; Dai, G.; et al. Immune homeostasis modulation by hydrogel-guided delivery systems: A tool for accelerated bone regeneration. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 6035–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, P.A.; Siegel, M.I. Bone biology and the clinical implications for osteoporosis. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Letaifa, R.; Klaylat, T.; Tarchala, M.; Gao, C.; Schneider, P.; Rosenzweig, D.H.; Martineau, P.A.; Gawri, R. Osteoimunology: An Overview of the Interplay of the Immune System and the Bone Tissue in Fracture Healing. Surgeries 2024, 5, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robling, A.G.; Castillo, A.B.; Turner, C.H. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2006, 8, 455–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florencio-Silva, R.; Sasso, G.R.; Sasso-Cerri, E.; Simões, M.J.; Cerri, P.S. Biology of Bone Tissue: Structure, Function, and Factors That Influence Bone Cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 421746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.; Horowitz, M.; Choi, Y. Osteoimmunology: Interactions of the bone and immune system. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 403–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, G.; D’Amelio, P.; Faccio, R.; Brunetti, G. The Interplay between the bone and the immune system. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 720504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arron, J.R.; Choi, Y. Bone versus Immune System. Nature 2000, 408, 535–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Xie, Q.; Lin, J.; Dong, H.; Zhuang, X.; Xian, R.; Liang, Y.; Li, S. Immunomodulatory Effects and Mechanisms of Two-Dimensional Black Phosphorus on Macrophage Polarization and Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Nanom. 2025, 20, 4337–4355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Zhao, C.-Z.; Wang, R.-Y.; Du, Q.-X.; Liu, J.-Y.; Pan, J. The crosstalk between macrophages and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in bone healing. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 511, Erratum in Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Patil, S.; Gao, Y.G.; Qian, A. The Bone Extracellular Matrix in Bone Formation and Regeneration. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šromová, V.; Sobola, D.; Kaspar, P. A Brief Review of Bone Cell Function and Importance. Cells 2023, 12, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizoguchi, T.; Ono, N. The diverse origin of bone-forming osteoblasts. J. Bone Min. Res. 2021, 36, 1432–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidson, K.; Abdallah, B.M.; Applegate, L.A.; Baldini, N.; Cenni, E.; Gomez-Barrena, E.; Granchi, D.; Kassem, M.; Konttinen, Y.T.; Mustafa, K.; et al. Bone regeneration and stem cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2011, 15, 718–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Qin, L.; Chen, S.; Huo, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, F.; Yi, W.; Mei, Y.; Xiao, G. Bone-derived factors mediate crosstalk between skeletal and extra-skeletal organs. Bone Res. 2025, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaquinta, M.R.; Montesi, M.; Mazzoni, E. Advances in Bone Biology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borciani, G.; Montalbano, G.; Baldini, N.; Cerqueni, G.; Vitale-Brovarone, C.; Ciapetti, G. Co-culture systems of osteoblasts and osteoclasts: Simulating in vitro bone remodeling in regenerative approaches. Acta Biomater. 2020, 108, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kular, J.; Tickner, J.; Chim, S.M.; Xu, J. An overview of the regulation of bone remodelling at the cellular level. Clin. Biochem. 2012, 45, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raggatt, L.J.; Partridge, N.C. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Bone Remodeling. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 25103–25108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsimbri, P. The Biology of Normal Bone Remodelling. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolamperti, S.; Villa, I.; Rubinacci, A. Bone remodeling: An operational process ensuring survival and bone mechanical competence. Bone Res. 2022, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenkre, J.S.; Bassett, J. The Bone Remodelling Cycle. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2018, 55, 308–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sims, N.A.; Martin, T.J. Coupling the activities of bone formation and resorption: A multitude of signals within the basic multicellular unit. BoneKEy Rep. 2014, 3, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Mehdi, A.A.; Srivastava, R.N.; Verma, N.S. Immunoregulation of bone remodelling. Int. J. Crit. Illn. Inj. Sci. 2012, 2, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, L.; Liu, F.; Wan, L.; Deng, Z. The effect of cytokines on osteoblasts and osteoclasts in bone remodeling in osteoporosis: A review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1222129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epsley, S.; Tadros, S.; Farid, A.; Kargilis, D.; Mehta, S.; Rajapakse, C.S. The Effect of Inflammation on Bone. Front. Physiol. 2021, 11, 511799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Ivashkiv, L.B. Negative regulation of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption by cytokines and transcriptional repressors. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2011, 13, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, N.; Ding, X.; Huang, R.; Jiang, R.; Huang, H.; Pan, X.; Min, W.; Chen, J.; Duan, J.A.; Liu, P.; et al. Bone Tissue Engineering in the Treatment of Bone Defects. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, S.; Verma, R.; Gouru, S.A.; Venkatesan, K.; Pandian, P.M.; Khan, M.I.; Deka, T.; Kumar, P. Emerging Technologies in Bone Tissue Engineering: A Review. J. Bionic Eng. 2025, 22, 2261–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauso, L.V.; La Fauci, V.; Longo, C.; Calabrese, G. Bone Tissue Engineering and Nanotechnology: A Promising Combination for Bone Regeneration. Biology 2024, 13, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.G.; Palermo, N.; Alibrandi, P.; Sciuto, E.L.; Del Gaudio, C.; Filardi, V.; Fazio, B.; Caccamo, A.; Oddo, S.; Calabrese, G.; et al. Physiologic Response Evaluation of Human Foetal Osteoblast Cells within Engineered 3D-Printed Polylactic Acid Scaffolds. Biology 2023, 12, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, G.; Franco, D.; Petralia, S.; Monforte, F.; Condorelli, G.G.; Squarzoni, S.; Traina, F.; Conoci, S. Dual-Functional Nano-Functionalized Titanium Scaffolds to Inhibit Bacterial Growth and Enhance Osteointegration. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, J.; Mukherjee, D. Osteoimmunomodulatory biomaterials: Engineering strategies, current progress, and future perspectives for bone regeneration. Appl. Mater. Today 2025, 44, 102753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, D.D. Overview of the immune response. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125 (Suppl. 2), S3–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevyrev, D.; Tereshchenko, V.; Berezina, T.N.; Rybtsov, S. Hematopoietic Stem Cells and the Immune System in Development and Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffinatto, L.; Groult, Y.; Iacono, J.; Sarrazin, S.; de Laval, B. Hematopoietic stem cell a reservoir of innate immune memory. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1491729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicherska-Pawłowska, K.; Wróbel, T.; Rybka, J. Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs), NOD-Like Receptors (NLRs), and RIG-I-Like Receptors (RLRs) in Innate Immunity. TLRs, NLRs, and RLRs Ligands as Immunotherapeutic Agents for Hematopoietic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, L.; Lei, Z. Critical signaling pathways in osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications for periprosthetic osteolysis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1639430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-awadh, A.N.; Delgado-Calle, J.; Tu, X.; Kuhlenschmidt, K.; Allen, M.R.; Plotkin, L.I.; Bellido, T. Parathyroid hormone receptor signaling induces bone resorption in the adult skeleton by directly regulating the RANKL gene in osteocytes. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 2797–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Lv, C.; Wang, F.; Gan, K.; Zhang, M.; Tan, W. Modulatory effect of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D 3 on IL1 β -induced RANKL, OPG, TNF α, and IL-6 expression in human rheumatoid synoviocyte MH7A. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 160123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marahleh, A.; Kitaura, H.; Ohori, F.; Kishikawa, A.; Ogawa, S.; Shen, W.R.; Qi, J.; Noguchi, T.; Nara, Y.; Mizoguchi, I. TNF-α Directly Enhances Osteocyte RANKL Expression and Promotes Osteoclast Formation. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jura-Półtorak, A.; Szeremeta, A.; Olczyk, K.; Zoń-Giebel, A.; Komosińska-Vassev, K. Bone Metabolism and RANKL/OPG Ratio in Rheumatoid Arthritis Women Treated with TNF-α Inhibitors. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, T.S.; Padrines, M.; The′oleyre, S.; Heymann, D.; Fortun, Y. IL-6, RANKL, TNF-alpha/IL-1: Interrelations in bone resorption pathophysiology. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2004, 15, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fukawa, Y.; Kayamori, K.; Tsuchiya, M.; Ikeda, T. IL-1 Generated by Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Stimulates Tumor-Induced and RANKL-Induced Osteoclastogenesis: A Possible Mechanism of Bone Resorption Induced by the Infiltration of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Yang, P.; Liu, H.; Zhang, F.; Li, M. IL-6 promotes low concentration of RANKL-induced osteoclastic differentiation by mouse BMMs through trans-signaling pathway. J. Mol. Histol. 2022, 53, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.A.; Tumber, A.; Papaioannou, S.; Meikle, M.C. The Cellular Actions of Interleukin-11 on Bone Resorption in Vitro. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 1564–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Gao, H.; Gan, X.; Liu, J.; Bao, C.; He, C. Roles of IL-11 in the regulation of bone metabolism. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1290130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacifici, R. The Role of IL-17 and TH17 Cells in the Bone Catabolic Activity of PTH. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Yu, M.; Tyagi, A.M.; Vaccaro, C.; Hsu, E.; Adams, J.; Bellido, T.; Weitzmann, M.N.; Pacifici, R. IL-17 Receptor Signaling in Osteoblasts/Osteocytes Mediates PTH-Induced Bone Loss and Enhances Osteocytic RANKL Production. J. Bone Min. Res. 2019, 34, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.J.; Wu, Z.F.; Yu, Y.H.; Wang, L.; Cheng, L. Effects of interleukin-7/interleukin-7 receptor on RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation and ovariectomy-induced bone loss by regulating c-Fos/c-Jun pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 7182–7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Blackwell, K.; Voznesensky, O.; Deb Roy, A.; Pilbeam, C. Prostaglandin E2 acts via bone marrow macrophages to block PTH-stimulated osteoblast differentiation in vitro. Bone 2013, 56, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mano, M.; Arakawa, T.; Mano, H.; Nakagawa, M.; Kaneda, T.; Kaneko, H.; Yamada, T.; Miyata, K.; Kiyomura, H.; Kumegawa, M.; et al. Prostaglandin E2 directly inhibits bone resorbing activity of isolated mature osteoclasts mainly through the EP4 receptor. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2000, 67, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, S.H.; Park, P.S.U.; Park-Min, K.H. The M-CSF receptor in osteoclasts and beyond. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1239–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, L.; Nácher-Juan, J.; Terencio, M.C.; Ferrándiz, M.L.; Alcaraz, M.J. Osteostatin Inhibits M-CSF+RANKL-Induced Human Osteoclast Differentiation by Modulating NFATc1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, N.C.; Kreutzmann, C.; Zimmermann, S.-P.; Niebergall, U.; Hellmeyer, L.; Goettsch, C.; Schoppet, M.; Hofbauer, L.C. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 stimulate the osteoclast inhibitor osteoprotegerin by human endothelial cells through the STAT6 pathway. J. Bone Min. Res. 2008, 23, 750–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirosavljevic, D.; Quinn, J.M.; Elliott, J.; Horwood, N.J.; Martin, T.J.; Gillespie, M.T. T-cells mediate an inhibitory effect of interleukin-4 on osteoclastogenesis. J. Bone Min. Res. 2003, 18, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayanagi, H.; Kim, S.; Taniguchi, T. Signaling crosstalk between RANKL and interferons in osteoclast differentiation. Arthritis Res. 2002, 4, S227–S232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.D.; Park-Min, K.H.; Shen, Z.; Fajardo, R.J.; Goldring, S.R.; McHugh, K.P.; Ivashkiv, L.B. Inhibition of RANK expression and osteoclastogenesis by TLRs and IFN-gamma in human osteoclast precursors. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 7223–7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.E.; Fox, S.W. Interleukin-10 inhibits osteoclastogenesis by reducing NFATc1 expression and preventing its translocation to the nucleus. BMC Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Grassi, F.; Ryan, M.R.; Terauchi, M.; Page, K.; Yang, X.; Weitzmann, M.N.; Pacifici, R. IFN-gamma stimulates osteoclast formation and bone loss in vivo via antigen-driven T cell activation. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaura, H.; Marahleh, A.; Ohori, F.; Noguchi, T.; Shen, W.-R.; Qi, J.; Nara, Y.; Pramusita, A.; Kinjo, R.; Mizoguchi, I. Osteocyte-Related Cytokines Regulate Osteoclast Formation and Bone Resorption. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalle Carbonare, L.; Cominacini, M.; Trabetti, E.; Bombieri, C.; Pessoa, J.; Romanelli, M.G.; Valenti, M.T. The bone microenvironment: New insights into the role of stem cells and cell communication in bone regeneration. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Fan, Y.; Wang, W.; Wu, R.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Z. Unraveling the causal role of TGF-βRII in osteoporosis and the potential of its associated differential genes as novel targets. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, T. TGFβ1 Regulates Human RANKL-Induced Osteoclastogenesis via Sup-pression of NFATc1 Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, B.F.; Xing, L. Functions of RANKL/RANK/OPG in bone modeling and remodeling. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 473, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, M.; Fabi, A.; Cognetti, F.; Gorini, S.; Caprio, M.; Fabbri, A. RANKL/RANK/OPG system beyond bone remodeling: Involvement in breast cancer and clinical perspectives. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Xie, X.; Gu, F.; Sui, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yu, T. Macrophage-Osteoclast Associations: Origin, Polarization, and Subgroups. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 778078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pande, S.; Scott, C.; Friesel, R. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor pretreatment of bone marrow progenitor cells regulates osteoclast differentiation based upon the stage of myeloid development. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 12450–12460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Jiang, K.; Lin, Z.; Qian, C.; Wu, M.; Xia, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, H.; et al. Regulation of bone homeostasis: Signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. MedComm 2024, 5, e657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahara, Y.; Nguyen, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Kamei, K.; Alman, B.A. The origins and roles of osteoclasts in bone development, homeostasis and repair. Development 2022, 149, dev199908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Cai, X.; Ren, F.; Ye, Y.; Wang, F.; Zheng, C.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, M. The Macrophage-Osteoclast Axis in Osteoimmunity and Osteo-Related Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 664871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grčević, D.; Sanjay, A.; Lorenzo, J. Interactions of B-lymphocytes and bone cells in health and disease. Bone 2023, 168, 116296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Q.; Yang, H.; Shi, Q. Macrophages and bone inflammation. J. Orthop. Translat. 2017, 10, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Hong, S.; Qian, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Yi, Q. Cross talk between the bone and immune systems: Osteoclasts function as antigen-presenting cells and activate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Blood 2010, 116, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.M.; Kim, K.W.; Yang, C.W.; Park, S.H.; Ju, J.H. Cytokine-mediated bone destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Immunol. Res. 2014, 2014, 263625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Huang, W.; Zhu, C.; Xu, Y.; Yang, H.; Bai, J.; Geng, D. Targeting strategies for bone diseases: Signaling pathways and clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guder, C.; Gravius, S.; Burger, C.; Wirtz, D.C.; Schildberg, F.A. Osteoimmunology: A Current Update of the Interplay Between Bone and the Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Terauchi, M.; Vikulina, T.; Roser-Page, S.; Weitzmann, M.N. B Cell Production of Both OPG and RANKL is Significantly Increased in Aged Mice. Open Bone J. 2014, 6, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Sözen, T.; Özışık, L.; Başaran, N.Ç. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur. J. Rheumatol. 2017, 4, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimai, H.P.; Fahrleitner-Pammer, A. Osteoporosis and Fragility Fractures: Currently available pharmacological options and future directions. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2022, 36, 101780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzmann, M.N.; Ofotokun, I. Physiological and pathophysiological bone turnover—Role of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, Y.; Routh, S.; Mukhopadhaya, A. Immunoporosis: Role of Innate Immune Cells in Osteoporosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 687037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, N.; Takayanagi, H. Autoimmune arthritis: The interface between the immune system and joints. Adv. Immunol. 2012, 115, 45–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Chavakis, T.; Lambris, J.D. Current understanding of periodontal disease pathogenesis and targets for host-modulation therapy. Periodontology 2000 2020, 84, 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satcher, R.L.; Zhang, X.H. Evolving cancer-niche interactions and therapeutic targets during bone metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, F.; Lymperi, S.; Méndez-Ferrer, S.; Saez, B.; Spencer, J.A.; Yeap, B.Y.; Masselli, E.; Graiani, G.; Prezioso, L.; Rizzini, E.L.; et al. Diabetes impairs hematopoietic stem cell mobilization by altering niche function. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 104ra101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.R.; Mychasiuk, R.; O’Brien, T.J.; Shultz, S.R.; McDonald, S.J.; Brady, R.D. Neurological heterotopic ossification: Novel mechanisms, prognostic biomarkers and prophylactic therapies. Bone Res. 2020, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzmann, M.N. Bone and the Immune System. Toxicol. Pathol. 2017, 45, 911–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qu, Y.; Chu, B.; Wu, T.; Pan, M.; Mo, D.; Li, L.; Ming, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. Research Progress on Biomaterials with Immunomodulatory Effects in Bone Regeneration. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e01209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, L.; Cao, J.; Dai, Q.; Qiu, D. New insight of immuno-engineering in osteoimmunomodulation for bone regeneration. Regen. Ther. 2021, 18, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrascal-Hernández, D.C.; Martínez-Cano, J.P.; Rodríguez Macías, J.D.; Grande-Tovar, C.D. Evolution in Bone Tissue Regeneration: From Grafts to Innovative Biomaterials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tupe, A.; Patole, V.; Ingavle, G.; Kavitkar, G.; Mishra Tiwari, R.; Kapare, H.; Baheti, R.; Jadhav, P. Recent Advances in Biomaterial-Based Scaffolds for Guided Bone Tissue Engineering: Challenges and Future Directions. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaricia, J.O.; Farzad, N.; Heath, T.J.; Simmons, J.; Morandini, L.; Olivares-Navarrete, R. Control of innate immune response by biomaterial surface topography, energy, and stiffness. Acta Biomater. 2021, 133, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, Z.; Brooks, P.J.; Barzilay, O.; Fine, N.; Glogauer, M. Macrophages, Foreign Body Giant Cells and Their Response to Implantable Biomaterials. Materials 2015, 8, 5671–5701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrescu, A.M.; Cimpean, A. The State of the Art and Prospects for Osteoimmunomodulatory Biomaterials. Materials 2021, 14, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xing, F.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, P.; Xu, J.; Luo, R.; Zhou, C.; Xiang, Z.; Rommens, P.M.; Liu, M.; et al. Integrated osteoimmunomodulatory strategies based on designing scaffold surface properties in bone regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 6718–6745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Chen, G.; Liu, M.; Xu, Z.; Chen, H.; Yang, L.; Lv, Y. Scaffold strategies for modulating immune microenvironment during bone regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. Mater. Biol. 2020, 108, 110411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Xiong, Y. Applications of bone regeneration hydrogels in the treatment of bone defects: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 887–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ke, Z.; Hu, G.; Tong, S. Hydrogel promotes bone regeneration through various mechanisms: A review. Biomed. Tech. 2024, 70, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tan, S.F.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C. From Macrophage Polarization to Clinical Translation: Immunomodulatory Hydrogels for Infection-Associated Bone Regeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1684357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biglari, N.; Razzaghi, M.; Afkham, Y.; Azimi, G.; Gross, J.D.; Samadi, A. Advanced biomaterials in immune modulation: The future of regenerative therapies. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 682, 125972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cytokines | Factor Effect on RANK/RANKL/OPG Axis | Immune Cell Source | Impact on Bone | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) | ↑ RANKL | Parathyroid gland (chief cells) | Stimulates osteoclastogenesis | [55] |

| 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 | ↑ RANKL, ↓ OPG | Synoviocytes | Enhances osteoclast differentiation | [56] |

| TNF-α | ↑ RANKL, ↓ OPG | Macrophages, T cells | Potent enhancer of bone resorption | [57,58] |

| IL-1 | ↑ RANKL, ↓ OPG | Macrophages, Monocytes | Drives inflammatory bone loss | [42,60] |

| IL-6 | ↑ RANKL | T cells, Macrophages | Promotes osteoclast activity | [41,61] |

| IL-11 | ↑ RANKL | Stromal cells | Supports osteoclastogenesis | [62,63] |

| IL-17 | ↑ RANKL | Th17 cells | Strongly pro-resorptive | [64,65] |

| IL-7 | ↑ RANKL (indirectly) | T cells | Contributes to osteoclast precursor priming | [41,66] |

| Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) | ↑ RANKL | Macrophages, stromal cells | Promotes bone resorption | [67,68] |

| M-CSF | ↑ RANKL expression | Macrophages, stromal cells | Facilitates osteoclast precursor survival | [69,70] |

| IL-13 | ↓ RANKL, ↑ OPG | Th2 cells | Suppresses osteoclast formation | [41,71] |

| IL-4 | ↓ RANKL; inhibits osteoclast differentiation | Th2 cells | Potently suppresses osteoclast formation | [41,71,72] |

| IFN-γ | ↓ RANKL signaling, inhibits stimulatory cytokines | T cells | Blocks osteoclast differentiation | [73,74] |

| IL-10 | ↓ NFATc1, alters RANKL/OPG ratio | Macrophages, T cells B cells | Inhibits osteoclastogenesis and mineralization | [75] |

| IL-18 | ↑ IFN-γ, ↑ GM-CSF | Dendritic cells, macrophages | Indirectly suppresses osteoclast precursors | [76,77] |

| IL-33 | ↑ IFN-γ, ↑ GM-CSF | Dendritic cells, macrophages | Indirectly suppresses osteoclast precursors | [78] |

| TGF-β | ↓ RANKL, ↑ OPG; modulates inflammatory cytokines | Macrophages, stromal cells | Anti-resorptive, promotes bone stability | [79] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Munaò, S.; Armeli, A.; Bonfiglio, D.; Iaconis, A.; Calabrese, G. Immune-Guided Bone Healing: The Role of Osteoimmunity in Tissue Engineering Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311642

Munaò S, Armeli A, Bonfiglio D, Iaconis A, Calabrese G. Immune-Guided Bone Healing: The Role of Osteoimmunity in Tissue Engineering Approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311642

Chicago/Turabian StyleMunaò, Serena, Alessandra Armeli, Desirèe Bonfiglio, Antonella Iaconis, and Giovanna Calabrese. 2025. "Immune-Guided Bone Healing: The Role of Osteoimmunity in Tissue Engineering Approaches" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311642

APA StyleMunaò, S., Armeli, A., Bonfiglio, D., Iaconis, A., & Calabrese, G. (2025). Immune-Guided Bone Healing: The Role of Osteoimmunity in Tissue Engineering Approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11642. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311642