The Effect of Silver Nanoparticle Addition on the Antimicrobial Properties of Poly(methyl methacrylate) Used for Fabrication of Dental Appliances: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Data Items

2.7. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.8. Effect Measures and Synthesis Methods

3. Results

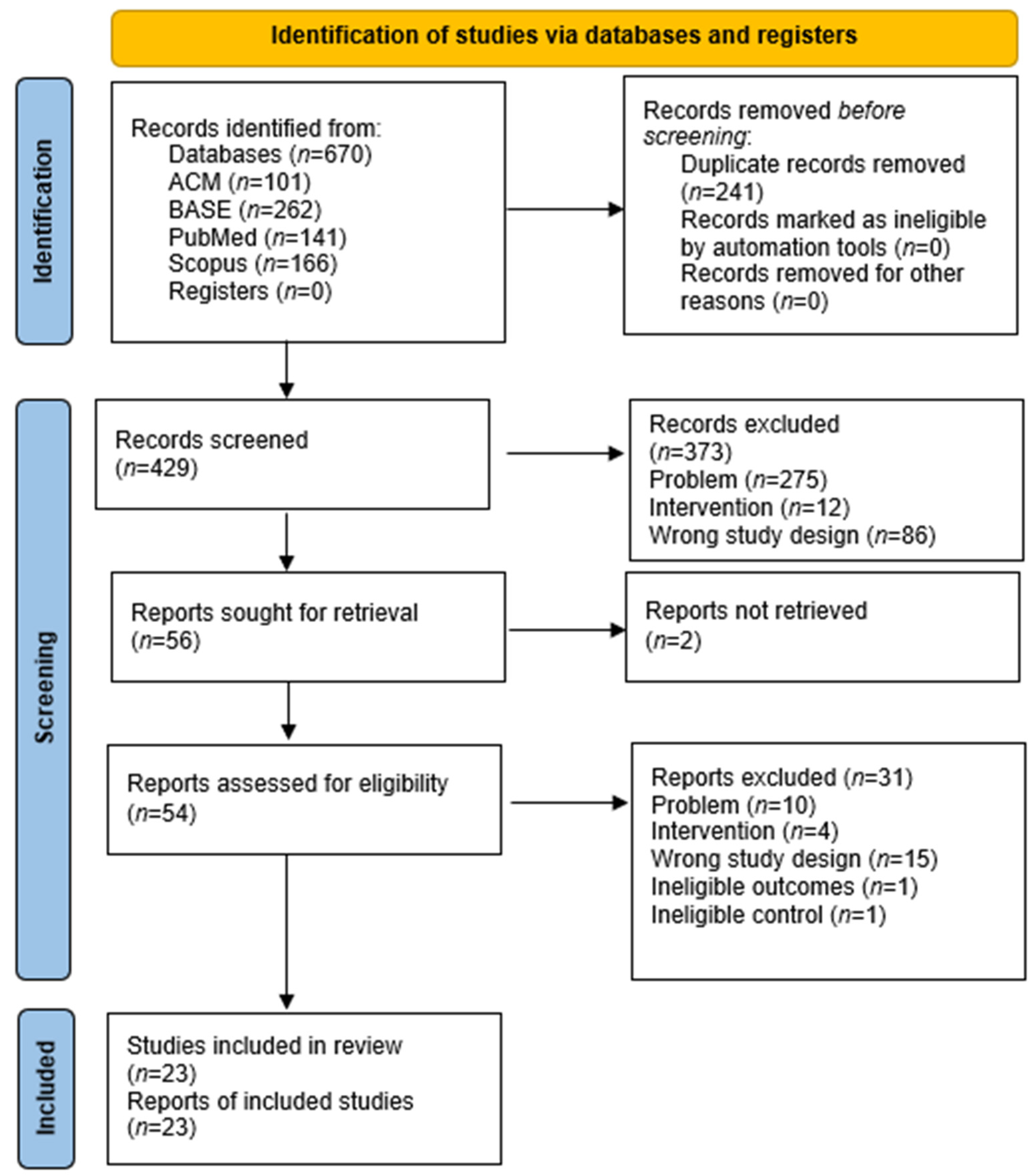

3.1. Selection of the Study

3.2. Results of Individual Studies

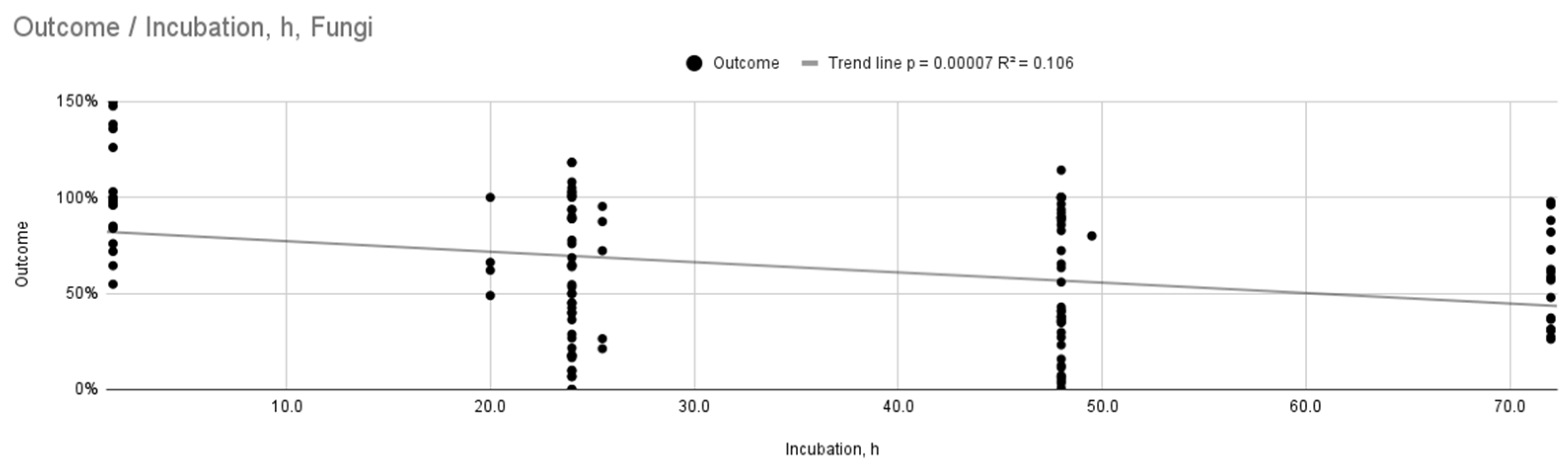

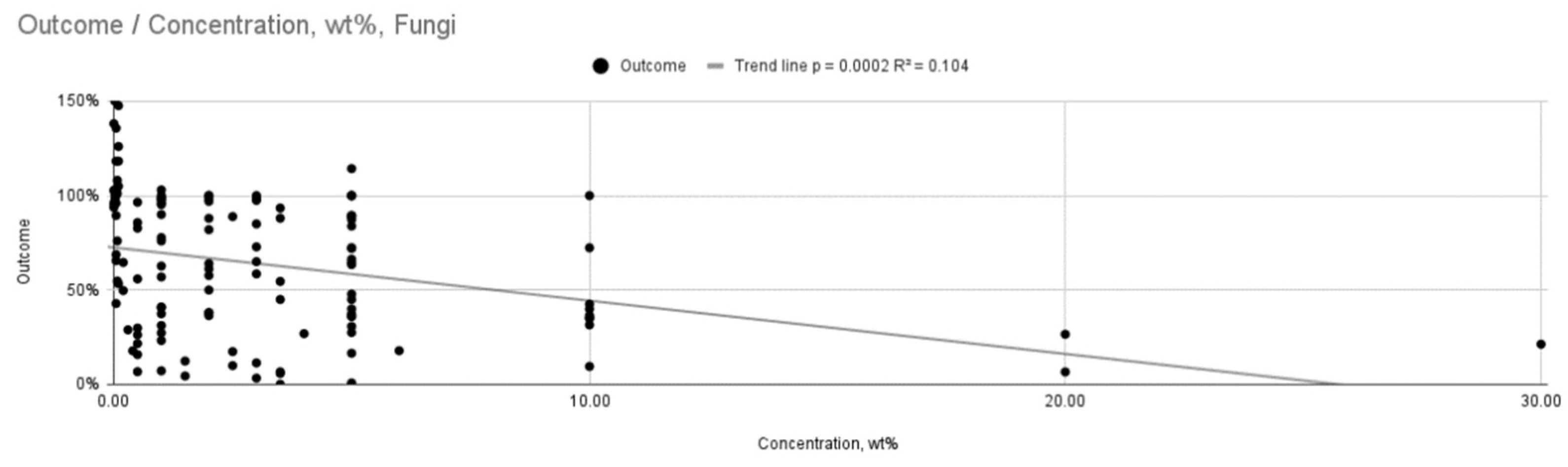

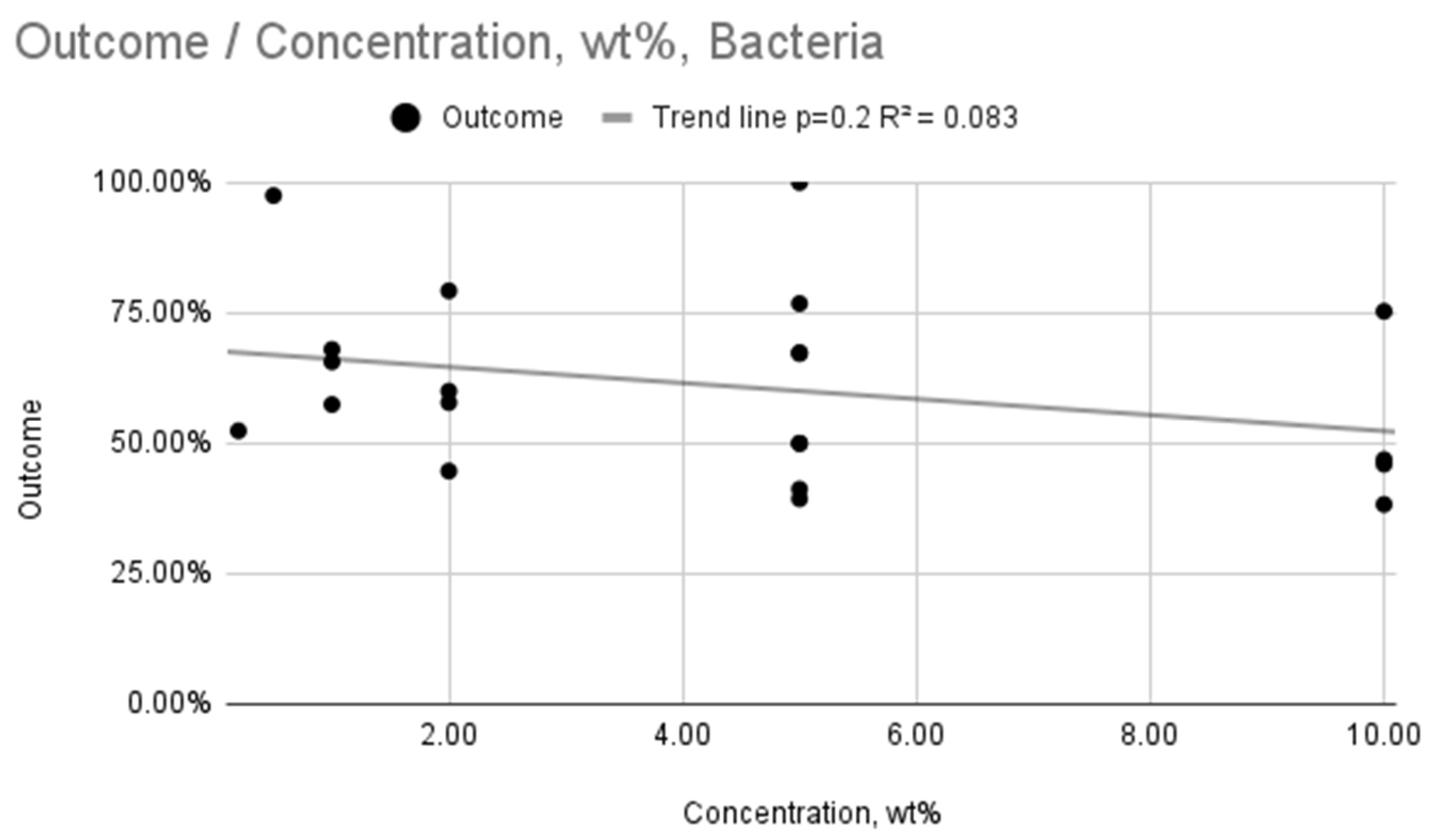

3.3. Results of Syntheses

3.4. Reporting Biases

4. Discussion

4.1. General Interpretations of Results

4.2. Strengths

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Applicability and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AgNPs | silver nano particles |

| N/A | not applicable |

| ND | Nanodiamond |

| PMMA | Poly(methyl methacrylate) |

| wt% | weight percent |

Appendix A

| Engine | Scope, Records |

|---|---|

| ACM | 3,797,063 |

| BASE | 414,202,196 |

| PubMed | over 37,000,000 |

| Scopus | over 97,300,000 |

| First Author, Publication Year | DOI | Specimen Dimension | Fabrication Method | Tested Fungi | Sample Contact Time(h) | AgNP Size, nm (Range, Mean) | Method of Assessment | AgNP Concentration, wt% | Result Fungi | Antifungal Properties, % * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acosta-Torres, 2012 [34] | 10.2147/IJN.S32391 | Circle 20 × 2 mm | microwave irradiation | C. albicans | 24 | 10–20 N/A | adherence; luminescent microbial cell viability assay (light relative units × 103) | N/A control | 4.8 11.5 | 41.74 |

| Arf, 2024 [35] | 10.24017/science.2024.1.6 | Circle 10 × 2 mm | cold cure acrylic | C. albicans | 48 | N/A 20 | anti-adherence assessment | 1.0 3.0 5.0 control | 82 10 2.4 300 (CFU × 104/mL) | 27.33 3.33 0.8 |

| Circle 10 × 2 mm | cold cure acrylic | C. albicans | 48 | N/A 20 | agar disc diffusion | 1.0 3.0 5.0 control | 0 0 0 (no effect) | 0 0 0 | ||

| De Matteis, 2019 [36] | 10.3390/ijms20194691 | N/A | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 24 | 17–23 20 | enumeration of the colony-forming units (CFU × 106/mL) | 3.0 3.5 control | 2.6 1.8 4 | 65 45 |

| N/A | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 48 | 17–23 20 | enumeration of the colony-forming units (CFU × 106/mL) | 3.0 3.5 control | †0.8 0.41 7 | 11.43 5.86 | ||

| N/A | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 24 | 17–23 20 | anti-adherence test (%) | 3.5 control | 36 66 | 54.55 | ||

| N/A | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 48 | 17–23 20 | anti-adherence test (%) | 3.5 control | 6 90 | 6.67 | ||

| N/A | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 24 | 17–23 20 | circularity | 3.5 control | 0.85 0.91 | 93.41 | ||

| N/A | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 48 | 17–23 20 | circularity | 3.5 control | 0.81 0.92 | 88.04 | ||

| Gad, 2022 [38] | 10.1016/j.prosdent.2020.08.021 | Circle 15 × 2 mm | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 48 | 5–60 20 | anti-adherence assessment (direct method) | 0.5 1.0 1.5 control (CFU/mL) | 322.4 147.2 91.4 2035.9 | 15.84 7.23 4.49 |

| Circle 15 × 2 mm | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 48 | 5–60 20 | anti-adherence assessment (slide count) | 0.5 1.0 1.5 control (CFU/mL) | 1075.6 838.6 446.3 3602.0 | 29.86 23.28 12.39 | ||

| Gligorijević, 2017 [39] | 10.5937/asn1775696G | Circle 10 × N/A mm | cold polymerized | C. albicans | 48 | N/A N/A | disc diffusion method | 2 5 10 control | 10 10 10 10 | 0 0 0 |

| Gopalakrishnan, 2019 [55] | 10.1080/00914037.2018.1552863 | N/A | compression moulding technique | C. albicans | 24 | 0–100 45 | anti-candidal assay before sonication | 1 2 5 10 control CFU | † 1800 † 1000 † 900 † 850 † 2000 | 90 50 45 42.5 |

| N/A | compression moulding technique | C. albicans | 48 | 0–100 45 | anti-candidal assay before sonication | 1 2 5 10 control CFU | † 2050 † 1900 † 1800 † 1750 † 5000 | 41 38 36 35 | ||

| N/A | compression moulding technique | C. albicans | 72 | 0–100 45 | anti-candidal assay before sonication | 1 2 5 10 control CFU | † 3700 † 3750 † 2000 † 2050 † 6500 | 56.92 57.69 30.77 31.54 | ||

| N/A | compression moulding technique | C. albicans | 24 | 0–100 45 | anti-candidal assay after sonication | 1 2 5 10 control CFU | † 1900 † 1600 † 1000 † 1000 † 2500 | 76 64 40 40 | ||

| N/A | compression moulding technique | C. albicans | 48 | 0–100 45 | anti-candidal assay after sonication | 1 2 5 10 control CFU | † 2200 † 2050 † 1950 † 1900 † 5400 | 40.74 37.96 36.11 35.19 | ||

| N/A | compression moulding technique | C. albicans | 72 | 0–100 45 | anti-candidal assay after sonication | 1 2 5 10 control CFU | † 4200 † 4100 † 2500 † 2450 † 6700 | 62.69 61.19 37.31 36.57 | ||

| Ismaeil, 2023 [40] | 10.4103/jioh.jioh_62_22 | Circle 10 × 2 mm | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 48 | N/A 40 | agar disc diffusion | 0.5 1.0 control | 17.9 26.7 10 | 179.0 267.0 |

| Circle 10 × 2 mm | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 72 | N/A 40 | elution | 0.5 1.0 control (CFUs/mL) | 1.50 1.78 5.70 | 26.32 31.23 | ||

| Nam, 2012 [41] | 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00489.x | Circle 20 × 3 mm | wet–heat poly-merisation | C. albicans | 25.5 | N/A N/A | exposure to bacterial suspension | 1 5 10 20 30 control | 362 332 275 101 81 380 | 95.26 87.37 72.37 26.58 21.32 |

| Li, 2016 [42] | 10.1111/ger.12142 | Circle 15 × 1 mm | heat-polymerized resin | C. albicans | 1.5 | N/A N/A | adhesion TFA(×104) | 1 2 3 5 control | 5.82 5.65 5.56 4.07 5.65 | 103.01 100 98.41 72.04 |

| Circle 15 × 1 mm | heat-polymerized resin | C. albicans | 1.5 | N/A N/A | adhesion live fungal cell percentage(%) | 1 2 3 5 control | 97.41 96.70 95.72 82.37 98.19 | 99.21 98.48 97.48 83.89 | ||

| Circle 15 × 1 mm | heat-polymerized resin | C. albicans | 1.5 | N/A N/A | adhesion the generation rate of germtubes (%) | 1 2 3 5 control | 91.55 90.48 79.33 60.26 93.31 | 98.11 96.97 85.02 64.58 | ||

| Circle 15 × 1 mm | heat-polymerized resin | C. albicans | 72 | N/A N/A | biofilm development Thickness of biofilm (um) | 1 2 3 5 control | 21.67 18.17 16.15 6.10 22.17 | 97.74 81.96 72.85 27.51 | ||

| Circle 15 × 1 mm | heat-polymerized resin | C. albicans | 72 | N/A N/A | biofilm development Live fungal cell percentage (%) | 1 2 3 5 control | 87.46 80.09 53.31 43.57 91.05 | 96.06 87.96 58.55 47.85 | ||

| Anaraki, 2017 [43] | 10.15171/PS.2017.31 | Circle 10 × 4 mm | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 24 | N/A 20 | biofilm formation (CFU) | 0.5 2.5 5 10 20 control | 127 102 97 56 39 586 | 21.67 17.41 16.55 9.56 6.66 |

| Peter, 2023 [44] | 10.4103/jmau.jmau_58_23 | Circle 5 × 1 mm | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 24 | 10–20 N/A | agar disc diffusion | 2 4 6 control | 13.71 18.58 27.96 5 | 274.2 371.6 559.2 |

| Mukai, 2023 [33] | 10.4317/jced.59766 | Block 10 × 10 × 3 mm | heat polymerized | C. albicans | 49.5 | N/A N/A | anti-adherence assessment CFU × 105 | N/A control | † 17,5 † 14 | 125 |

| Palaskar, 2024 [45] | 10.4103/jips.jips_423_23 | Circle 10 × 3 mm | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 24 | 0–10 N/A | anti-adherence assessment | 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 control | 78.66 73.33 42.66 26.33 10 147.5 | 53.33 49.72 28.92 17.85 6.78 |

| Pinheiro, 2021 [46] | 10.1590/1980-5373-MR-2020-0115 | Circle 15 × 2 mm | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 24 | N/A 50 | XTT assay protocol | 1.0 2.5 5.0 control (spectrofotometer and formazon) | 0.07 0.08 0.08 0.09 | 77.78 88.89 88.89 |

| Sato, 2018 [47] | 10.14295/bds.2018.v21i1.1534 | Circle 5 × 2 mm | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 48 | N/A | biofilm formation (CFU) | N/A N/A control | 4.95 5.05 5.4 | 91.67 93.52 |

| Sonkol, 2024 [48] | DOI: 10.4103/tdj.tdj_30_23 | Circle 15 × 3 mm | conventional method | C. albicans | 48 | N/A N/A | agar disc diffusion | 5 control | 16.8 15 | 112.0 |

| Souza Neto, 2019 [49] | 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2018.10.009 | Block 60 × 10 × 3 mm | heat-polymerized | C. glabrata | 48 | 3–13 6.7 | total biofilm biomass(CV) | 0.05 0.5 5.0 control | † 0.19 † 0.24 † 0.21 † 0.29 | 65.52 82.76 72.41 |

| Block 60 × 10 × 3 mm | heat-polymerized | C. glabrata | 48 | 3–13 6.7 | metabolic activity (XTT) | 0.05 0.5 5.0 control | † 0.03 † 0.06 † 0.08 † 0.07 | 42.86 85.71 114.29 | ||

| Block 60 × 10 × 3 mm | heat-polymerized | C. glabrata | 48 | 3–13 6.7 | quantification of biofilm cultivable cells log10 CFU/cm2 | 0.05 0.5 5.0 control | † 5.1 † 5.5 † 5.1 † 5.7 | 89.47 96.49 89.47 | ||

| Suganya, 2014 [50] | 10.4103/0970-9290.135923 | Circle 5 × 1 mm | heat polymerized acrylic resin | C. albicans | 24 | 10–20 N/A | enumeration of the colony- forming units(CFU/mL) | 2.5 3.5 5.0 control | 104 102 10 105 | 10 0.1 0.01 |

| Sun, 2021 [51] | 10.4012/dmj.2020-129 | Circle 10 × 2 mm | N/A | C. albicans | 20 | 40–60 N/A | agar disc diffusion (after 0 days) | powder 5% Solution N/A control | 15.08 20.47 10 | 150.8 204.7 |

| Circle 10 × 2 mm | N/A | C. albicans | 20 | 40–60 N/A | agar disc diffusion (after 7 days) | powder 5% Solution N/A control | 10 16.1 10 | 100 161 | ||

| Thabet, 2022 [52] | 10.21608/edj.2022.111973.1919 | Circle 15 × 2 mm | heat-polymerized | C. albicans | 48 | 0–45 N/A | anti-adherence assessment (direct culture, serial dilution) | 5.0 control (CFUs) | 32.44 51.12 | 63.46 |

| Vaiyshnavi, 2022 [53] | 10.4103/jips.jips_574_21 | Circle 50 × 1 mm | high-impact injection- moulded | C. albicans | 24 | N/A N/A | agar disc diffusion | 0.05 0.2 control (MM) | † 72.7 † 77.4 50 | 145.4 154.8 |

| Wady, 2012 [54] | 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05293.x | Circle 13.8 × 2 mm | microwave irradiation | C. albicans | 1.5 | N/A 9 | XTT adherence assay (after 0 days storage) | 0.003 0.025 0.05 0.075 0.1 control | † 0.48 † 0.49 † 0.48 † 0.38 † 0.63 † 0.5 | † 96.0 † 98.0 † 96.0 † 76.0 † 126.0 |

| Circle 13.8 × 2 mm | microwave irradiation | C. albicans | 1.5 | N/A 9 | XTT adherence assay (after 7 days storage) | 0.003 0.025 0.05 0.075 0.1 control | † 0.58 † 0.63 † 0.57 † 0.23 † 0.62 † 0.42 | † 138.1 † 150.0 † 135.71 † 54.76 † 147.62 | ||

| Circle 13.8 × 2 mm | microwave irradiation | C. albicans | 24 | N/A 9 | XTT biofilm assay (after 0 days storage) | 0.003 0.025 0.05 0.075 0.1 control | † 1.5 † 1.65 † 1.6 † 1.62 † 1.68 † 1.6 | † 93.75 † 103.13 † 100 † 101.25 † 105 | ||

| Circle 13.8 × 2 mm | microwave irradiation | C. albicans | 24 | N/A 9 | XTT biofilm assay (after 7 days storage) | 0.003 0.025 0.05 0.075 0.1 control | † 1.52 † 1.49 † 1.75 † 1.6 † 1.75 † 1.48 | † 102.70 † 100.68 † 118.24 † 108.11 † 118.24 |

| First Author, Publication Year | DOI | Specimen Dimension | Fabrication Method | Tested Bacteria | Sample Contact Time (h) | AgNP Size, nm (Range, Mean) | Method of Assessment | AgNP Concentration, wt% | Result Bacteria | Antibacterial Properties, % * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fan, 2011 [37] | 10.1016/j.dental.2010.11.008 | Circle 9.53 × 1.59 mm | chemical cured acrylic resin | Streptococcus mutans | 120 | 2–18 N/A | growth inhibition | 0.2 0.5 control (%) | 52.4 97.5 0 | 52.4 97.5 |

| Gligorijević, 2017 [39] | 10.5937/asn1775696G | Circle 10 × N/A mm | cold polymerized | Staphylococcus aureus | 24 | N/A N/A | disc diffusion method | 2 5 10 control | 12.62 13.01 13.28 10.00 | 126.2 130.1 132.8 |

| Gopalakrishnan, 2019 [55] | 10.1080/00914037.2018.1552863 | N/A | compression moulding technique | Streptococcus mutans | 240 | 0–100 45 | anti-biofilm assay (cells) | 1 2 5 10 control | † 1700 † 1500 † 1250 † 1150 † 2500 | † 68.0 † 60.0 † 50.0 † 46.0 |

| N/A | compression moulding technique | Streptococcus mutans | 480 | 0–100 45 | anti-biofilm assay (cells) | 1 2 5 10 control | † 2100 † 1850 † 1600 † 1500 † 3200 | † 65.63 † 57.81 † 50.0 † 46.88 | ||

| N/A | compression moulding technique | Streptococcus mutans | 720 | 0–100 45 | anti-biofilm assay (cells) | 1 2 5 10 control | † 2700 † 2100 † 1850 † 1800 † 4700 | † 57.45 † 44.68 † 39.36 † 38.30 | ||

| Sun, 2021 [51] | 10.4012/dmj.2020-129 | Circle 10 × 2 mm | N/A | Escherichia coli | 20 | 40–60 N/A | agar disc diffusion (after 0 days) | powder 5% solution N/A control | 14.88 20.2 10 | 148.8 202.0 |

| Circle 10 × 2 mm | N/A | Streptococcus mutans | 20 | 40–60 N/A | agar disc diffusion (after 0 days) | powder 5% solution N/A control | 24.26 25.4 10 | 242.6 254.0 | ||

| Circle 10 × 2 mm | N/A | Escherichia coli | 20 | 40–60 N/A | agar disc diffusion (after 7 days) | powder 5% solution N/A control | 10 14.9 10 | 100.0 149.0 | ||

| Circle 10 × 2 mm | N/A | Streptococcus mutans | 20 | 40–60 N/A | agar disc diffusion (after 7 days) | powder 5% solution N/A control | 14.83 20.73 10 | 148.3 207.3 |

References

- Zafar, M.S. Prosthodontic Applications of Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA): An Update. Polymers 2020, 12, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gungor, H.; Gundogdu, M.; Yesil Duymus, Z. Investigation of the Effect of Different Polishing Techniques on the Surface Roughness of Denture Base and Repair Materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 1271–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, S. Polymers in Dentistry. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H 1998, 212, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galant, K.; Turosz, N.; Chęcińska, K.; Chęciński, M.; Cholewa-Kowalska, K.; Karwan, S.; Chlubek, D.; Sikora, M. Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) Incorporation into Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) for Dental Appliance Fabrication: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Mechanical Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.K. A to Z Orthodontics. Volume 10: Removable Orthodontic Appliance; PPSP Publication: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-967-5547-99-7. [Google Scholar]

- Carlino, F.; Claudio, P.P.; Tomeo, M.; Cortese, A. Mandibular Bi-Directional Distraction Osteogenesis: A Technique to Manage Both Transverse and Sagittal Mandibular Diameters via a Lingual Tooth-Borne Acrylic Plate and Double-Hinge Bone Anchorage. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chęcińska, K.; Chęciński, M.; Sikora, M.; Nowak, Z.; Karwan, S.; Chlubek, D. The Effect of Zirconium Dioxide (ZrO2) Nanoparticles Addition on the Mechanical Parameters of Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies. Polymers 2022, 14, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, E.; Majoufre, C.; Bondaz, M.; Courtemanche, A.; Berger, M.; Bouletreau, P. Current Status of Surgical Planning and Transfer Methods in Orthognathic Surgery. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 119, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, P.; Kocacikli, M. Three-Dimensional Printing Technologies in the Fabrication of Maxillofacial Prosthesis: A Case Report. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 2020, 43, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Asghar, M.; Din, S.U.; Zafar, M.S. Chapter 8—Thermoset Polymethacrylate-Based Materials for Dental Applications. In Materials for Biomedical Engineering; Grumezescu, V., Grumezescu, A.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 273–308. ISBN 978-0-12-816874-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sawada, T.; Sawada, T.; Kumasaka, T.; Hamada, N.; Shibata, T.; Nonami, T.; Kimoto, K. Self-Cleaning Effects of Acrylic Resin Containing Fluoridated Apatite-Coated Titanium Dioxide. Gerodontology 2014, 31, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Hamada, N.; Kimoto, K.; Sawada, T.; Sawada, T.; Kumada, H.; Umemoto, T.; Toyoda, M. Antifungal Effect of Acrylic Resin Containing Apatite-Coated TiO2 Photocatalyst. Dent. Mater. J. 2007, 26, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.M.; Rahoma, A.; Al-Thobity, A.M.; ArRejaie, A.S. Influence of Incorporation of ZrO2 Nanoparticles on the Repair Strength of Polymethyl Methacrylate Denture Bases. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 5633–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacali, C.; Badea, M.; Moldovan, M.; Sarosi, C.; Nastase, V.; Baldea, I.; Chiorean, R.S.; Constantiniuc, M. The Influence of Graphene in Improvement of Physico-Mechanical Properties in PMMA Denture Base Resins. Materials 2019, 12, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonas, P.; Milward, P.; McAndrew, R. Denture Cleanliness and Hygiene: An Overview. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 233, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.H.; Martani, N.S.H.; Mohammed, J.R. The Impact of Different Occlusal Guard Materials on Candida Albicans Proliferationin the Oral Cavity. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2024, 70, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Shujaulla, S.; Mittal, G.K.; Guliani, H. Applications of silver nanoparticles in prosthodontics: A new appraisal. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 6, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendorf, T.M.; Walker, D.M. Denture Stomatitis: A Review. J. Oral. Rehabil. 1987, 14, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Visschere, L.M.; Grooten, L.; Theuniers, G.; Vanobbergen, J.N. Oral Hygiene of Elderly People in Long-Term Care Institutions--a Cross-Sectional Study. Gerodontology 2006, 23, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, D.E.; Moorthy, A.; Moneley, J.O.; Jabra-Rizk, M.A.; Sultan, A.S. Denture Stomatitis—An Interdisciplinary Clinical Review. J. Prosthodont. 2023, 32, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redtenbacher, J. Ueber Die Zerlegungsprodukte Des Glyceryloxydes Durch Trockene Destillation. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1843, 47, 113–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oves, M.; Aslam, M.; Rauf, M.A.; Qayyum, S.; Qari, H.A.; Khan, M.S.; Alam, M.Z.; Tabrez, S.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Ismail, I.M.I. Antimicrobial and Anticancer Activities of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized from the Root Hair Extract of Phoenix Dactylifera. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2018, 89, 429–443, Erratum in Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 19, 111499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, C.-N.; Ho, C.-M.; Chen, R.; He, Q.-Y.; Yu, W.-Y.; Sun, H.; Tam, P.K.-H.; Chiu, J.-F.; Che, C.-M. Silver Nanoparticles: Partial Oxidation and Antibacterial Activities. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 12, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marambio-Jones, C.; Hoek, E.M.V. A Review of the Antibacterial Effects of Silver Nanomaterials and Potential Implications for Human Health and the Environment. J. Nanopart Res. 2010, 12, 1531–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ershov, V.A.; Ershov, B.G. Effect of Silver Nanoparticle Size on Antibacterial Activity. Toxics 2024, 12, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.-M.; Hu, L.-G.; Yan, X.-T.; Zhao, X.-C.; Zhou, Q.-F.; Cai, Y.; Jiang, G.-B. Surface Ligand Controls Silver Ion Release of Nanosilver and Its Antibacterial Activity against Escherichia Coli. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 3193–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmuganathan, R.; Karuppusamy, I.; Saravanan, M.; Muthukumar, H.; Ponnuchamy, K.; Ramkumar, V.S.; Pugazhendhi, A. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Biomedical Applications—A Comprehensive Review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 2650–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaisankar, A.I.; Rajeshkumar, S.; Ezhilarasan, D. Applications of Silver Nanoparticles in Dentistry. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 11, 1126–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubchandani, M.; Thosar, N.R.; Dangore-Khasbage, S.; Srivastava, R. Applications of Silver Nanoparticles in Pediatric Dentistry: An Overview. Cureus 2022, 14, e26956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharkhavy, K.V.; Pushpalatha, C.; Anandakrishna, L. Silver, the Magic Bullet in Dentistry—A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, R.A.; Chaubal, T.V.; Joshi, C.P.; Bapat, P.R.; Choudhury, H.; Pandey, M.; Gorain, B.; Kesharwani, P. An Overview of Application of Silver Nanoparticles for Biomaterials in Dentistry. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2018, 91, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgamily, H.; El-Sayed, H.; Abdelnabi, A. The Antibacterial Effect of Two Cavity Disinfectants against One of Cariogenic Pathogen: An In Vitro Comparative Study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2018, 9, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, M.; Iegami, C.; Cai, S.; Stegun, R.; Galhardo, A.; Costa, B. Antimicrobial Effect of Silver Nanoparticles on Polypropylene and Acrylic Resin Denture Bases. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2023, 15, e38–e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta-Torres, L.S.; Mendieta, I.; Nuñez-Anita, R.E.; Cajero-Juárez, M.; Castaño, V.M. Cytocompatible Antifungal Acrylic Resin Containing Silver Nanoparticles for Dentures. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 4777–4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arf, A.N.; Kareem, F.A.; Khdir, Y.K.; Zafar, M.S. Assessment of the Antifungal Activity of PMMA-MgO and PMMA-Ag Nanocomposite. Kurd. J. Appl. Res. 2024, 9, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Matteis, V.; Cascione, M.; Toma, C.C.; Albanese, G.; De Giorgi, M.L.; Corsalini, M.; Rinaldi, R. Silver Nanoparticles Addition in Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Dental Matrix: Topographic and Antimycotic Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Chu, L.; Rawls, H.R.; Norling, B.K.; Cardenas, H.L.; Whang, K. Development of an Antimicrobial Resin—A Pilot Study. Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.M.; Abualsaud, R.; Rahoma, A.; Al-Thobity, A.M.; Akhtar, S.; Fouda, S.M. Double-Layered Acrylic Resin Denture Base with Nanoparticle Additions: An in Vitro Study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorijevic, N.; Kostic, M.; Tacic, A.; Nikolic, L.; Nikolic, V. Antimicrobial Properties of Acrylic Resins for Dentures Impregnated with Silver Nanoparticles. Acta Stomatol. Naissi 2017, 33, 1696–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaeil, M.A.; Ebrahim, M. Antifungal Effect of Acrylic Resin Denture Base Containing Different Types of Nanomaterials: A Comparative Study. J. Int. Oral Heal. 2023, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.; Lee, C.; Lee, C. Antifungal and Physical Characteristics of Modified Denture Base Acrylic Incorporated with Silver Nanoparticles. Gerodontology 2012, 29, e413–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, J.; Lan, J.; Qi, Q. Effect of a Denture Base Acrylic Resin Containing Silver Nanoparticles on Candida Albicans Adhesion and Biofilm Formation. Gerodontology 2016, 33, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaraki, M.R.; Jangjoo, A.; Alimoradi, F.; Dizaj, S.M.; Lotfipour, F. Comparison of Antifungal Properties of Acrylic Resin Reinforced with ZnO and Ag Nanoparticles. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 23, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, M.; Bembalagi, M.; Kanathila, H.; Santhosh, V.N.; Roy, T.R.; Monsy, M. Comparative Evaluation of Antifungal Property of Acrylic Resin Reinforced with Magnesium Oxide and Silver Nanoparticles and Their Effect on Cytotoxic Levels: An In Vitro Study. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaskar, J.N.; Hindocha, A.D.; Mishra, A.; Gandagule, R.; Korde, S. Evaluating the Antifungal Effectiveness, Leaching Characteristics, Flexural Strength, and Impact Strength of Polymethyl Methacrylate Added with Small-Scale Silver Nanoparticles — An in Vitro Study. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2024, 24, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro, M.C.R.; Carneiro, J.A.O.; Pithon, M.M.; Martinez, E.F. Thermopolymerized Acrylic Resin Immersed or Incorporated with Silver Nanoparticle: Microbiological, Cytotoxic and Mechanical Effect. Mater. Res. 2021, 24, e20200115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.P.; Conjo, C.I.; Rossoni, R.D.; Junqueira, J.C.; de Melo, R.M.; Durán, N.; Borges, A.L.S. Antimicrobial and Mechanical Acrylic Resin Properties with Silver Particles Obtained from Fusarium Oxysporum. Braz. Dent. Sci. 2018, 21, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkol, N.M.A.E.-F.; Kashef, N.A.K.; El-Segai, A.A.E.M.; El-Badry, A.S.M. Effect of Denture Base Acrylic Resin Containing Silver Nanoparticles on Candida Albicans Adhesion and Its Release in Artificial Saliva. Tanta Dent. J. 2024, 21, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, F.N.d.S.; Sala, R.L.; Fernandes, R.A.; Xavier, T.P.O.; Cruz, S.A.; Paranhos, C.M.; Monteiro, D.R.; Barbosa, D.B.; Delbem, A.C.B.; de Camargo, E.R. Effect of synthetic colloidal nanoparticles in acrylic resin of dental use. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 112, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganya, S.; Ahila, S.; Kumar, B.; Kumar, M. Evaluation and comparison of anti-Candida effect of heat cure polymethylmethacrylate resin enforced with silver nanoparticles and conventional heat cure resins: An in vitro study. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2014, 25, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Guo, X.; Zhang, T.; Guo, H. Characterization and Evaluation of a Novel Silver Nanoparticles-Loaded Polymethyl Methacrylate Denture Base: In Vitro and in Vivo Animal Study. Dent. Mater. J. 2021, 40, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, Y.; Moustafa, D.; El Shafei, S. The Effect Of Silver Versus Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles On Poly Methylmethacrylate Denture Base Material. Egypt. Dent. J. 2022, 68, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jei, J.; Vaiyshnavi, W.; Kumar, B. Effect of silver nanoparticles on wettability, anti-fungal effect, flexural strength, and color stability of injection-molded heat-cured polymethylmethacrylate in human saliva. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2022, 22, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wady, A.; Machado, A.; Zucolotto, V.; Zamperini, C.; Berni, E.; Vergani, C. Evaluation of Candida albicans adhesion and biofilm formation on a denture base acrylic resin containing silver nanoparticles. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 112, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; T., A.M.; Mozetič, M.; P., J.V.; Jose, J.; Thomas, S.; Kalarikkal, N. Development of biocompatible and biofilm-resistant silver-poly(methylmethacrylate) nanocomposites for stomatognathic rehabilitation. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater. 2019; 69, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochvaldová, L.; Panáček, D.; Válková, L.; Večeřová, R.; Kolář, M.; Prucek, R.; Kvítek, L.; Panáček, A.E. Coli and S. Aureus Resist Silver Nanoparticles via an Identical Mechanism, but through Different Pathways. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaymat, T.M.; El Badawy, A.M.; Genaidy, A.; Scheckel, K.G.; Luxton, T.P.; Suidan, M. An Evidence-Based Environmental Perspective of Manufactured Silver Nanoparticle in Syntheses and Applications: A Systematic Review and Critical Appraisal of Peer-Reviewed Scientific Papers. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.-M.; Mizuta, Y.; Akagi, J.-I.; Toyoda, T.; Sone, M.; Ogawa, K. Size-Dependent Acute Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles in Mice. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 2018, 31, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Rong, K.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, R. Size-Dependent Antibacterial Activities of Silver Nanoparticles against Oral Anaerobic Pathogenic Bacteria. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2013, 24, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Lim, D.W.; Choi, J. Assessment of Size-Dependent Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Properties of Silver Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 763807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakand, S.; Hayes, A. Toxicological Considerations, Toxicity Assessment, and Risk Management of Inhaled Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, T.D.; Wilson, M. The Effects of Surface Roughness and Type of Denture Acrylic on Biofilm Formation by Streptococcus Oralis in a Constant Depth Film Fermentor. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 91, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, Z.É.; Nagy, L.; Kelemen, K.; Cavalcante, B.G.N.; Gede, N.; Hegyi, P.; Bányai, D.; Köles, L.; Márton, K. Milling Has Superior Mechanical Properties to Other Fabrication Methods for PMMA Denture Bases: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Dent. Mater. 2025, 41, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buergers, R.; Rosentritt, M.; Handel, G. Bacterial Adhesion of Streptococcus Mutans to Provisional Fixed Prosthodontic Material. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2007, 98, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, B.C.; Thomas, C.J.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Harty, D.W.S.; Knox, K.W. Candida-associated Denture Stomatitis. Aetiology and Management: A Review: Part1. Factors Influencing Distribution of Candida Species in the Oral Cavity. Aust. Dent. J. 1998, 43, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, B.C.; Thomas, C.J.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Harty, D.W.S.; Knox, K.W. Candida-associated Denture Stoma Titis. Aetiology and Management: A Review. Part 2. Oral Diseases Caused by Candida Species. Aust. Dent. J. 1998, 43, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, L.E.; Smith, K.; Williams, C.; Nile, C.J.; Lappin, D.F.; Bradshaw, D.; Lambert, M.; Robertson, D.P.; Bagg, J.; Hannah, V.; et al. Dentures Are a Reservoir for Respiratory Pathogens. J. Prosthodont. 2016, 25, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, B.C.; Thomas, C.J.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Harty, D.W.S.; Knox, K.W. Candida-associated Denture Stomatitis. Aetiology and Management: A Review. Part 3. Treatment of Oral Candidosis. Aust. Dent. J. 1998, 43, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, C.; Pascale, M.; Contaldo, M.; Esposito, V.; Busciolano, M.; Milillo, L.; Guida, A.; Petruzzi, M.; Serpico, R. Candida-Associated Denture Stomatitis. Med. Oral 2011, 16, e139–e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.J.; Koo, H.; Hajishengallis, G. The Oral Microbiota: Dynamic Communities and Host Interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bakri, I.A.; Harty, D.; Al-Omari, W.M.; Swain, M.V.; Chrzanowski, W.; Ellakwa, A. Surface Characteristics and Microbial Adherence Ability of Modified Polymethylmethacrylate by Fluoridated Glass Fillers. Aust. Dent. J. 2014, 59, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, C.; Takakuda, K.; Wakabayashi, N. Reduction of Candida Biofilm Adhesion by Incorporation of Prereacted Glass Ionomer Filler in Denture Base Resin. J. Dent. 2016, 44, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangal, U.; Kim, J.-Y.; Seo, J.-Y.; Kwon, J.-S.; Choi, S.-H. Novel Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) Containing Nanodiamond to Improve the Mechanical Properties and Fungal Resistance. Materials 2019, 12, 3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; El-Fiqi, A.; Jo, J.-K.; Kim, D.-A.; Kim, S.-C.; Jun, S.-K.; Kim, H.-W.; Lee, H.-H. Development of Long-Term Antimicrobial Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) by Incorporating Mesoporous Silica Nanocarriers. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Singh, R.D.; Khan, H.; Gangopadhyay, S.; Mittal, S.; Singh, V.; Arjaria, N.; Shankar, J.; Roy, S.K.; Singh, D.; et al. Oral Subchronic Exposure to Silver Nanoparticles Causes Renal Damage through Apoptotic Impairment and Necrotic Cell Death. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zheng, J. Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles: Structural Effects. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, e1701503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, M.; Sikder, M.T.; Rahman, M.M.; Ullah, A.K.M.A.; Hossain, K.F.B.; Banik, S.; Hosokawa, T.; Saito, T.; Kurasaki, M. A Systematic Review on Silver Nanoparticles-Induced Cytotoxicity: Physicochemical Properties and Perspectives. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Problem | Intraoral dental appliances made of PMMA with AgNPs | The additive of other types of nanoparticles, i.e., zircon, other materials than PMMA, not dental appliances |

| Intervention | Test of antibacterial or antifungal properties | Test performed more than 7 days after fabrication |

| Comparison | PMMA without the addition of AgNPs (control group) | Control sample prepared using a method different from the test sample |

| Outcome | Reduction in the number of CFU, biofilm formation, or antifungal effect etc. | Non-quantitative outcomes |

| Timeframe | No limit | Preprints |

| Study design | Primary studies; in vitro studies | Non-original/non-English research, Reviews, book chapters, or book fragments |

| Data Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Specimen dimension | Dimensions of the test sample and shape of it |

| Fabrication Method | Method of producing a PMMA sample |

| Tested bacteria/fungi | Specimen of bacteria or fungi used in testing |

| Sample contact time | Contact time of the sample with the bacterial/fungal suspension |

| AgNP size | Mean or range of nanoparticle diameter |

| Method of assessment | Method of assessing antimicrobial properties |

| AgNP concentration | Number of nanoparticles in PMMA sample, percentage by weight |

| Result fungi | Test results obtained for a sample containing fungi |

| Result bacteria | Test results obtained for a sample containing bacteria |

| Microorganism Category | Primary Species Tested | No. of Studies | AgNP Concentration Range (wt%) | Incubation Time Range (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | C. albicans (21 studies), C. glabrata (1 study) | 22 | 0.003% to 30% | 1.5 h to 72 h |

| Bacteria | S. mutans (3 studies), S. aureus (1 study), E. coli (1 study) | 4 | 0.2% to 10% | 20 h to 720 h |

| Microorganism | Analyzed Variable | No. of Studies (n) | Regression Analysis Outcome (Conclusion) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | AgNP Concentration (wt%) | 22 | Weak, statistically significant relationship (R2 = 0.104, p < 0.001) |

| Fungi | Incubation Time (h) | 22 | Weak, statistically significant relationship (R2 = 0.106, p < 0.001) |

| Bacteria | AgNP Concentration (wt%) | 4 | Weak, statistically insignificant relationship (R2 = 0.083, p = 0.2) |

| Bacteria | Incubation Time (h) | 4 | Weak, statistically significant relationship (R2 = 0.196, p = 0.03) |

| Pair of Variables | Number of Variables (n) | Tau Kendall (τ) | Significance Level (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| incubation time, h vs. concentration, wt% | 130 | 0.181 | 0.002 |

| incubation time, h vs. outcome | 136 | –0.237 | 0.00004 |

| concentration, wt% vs. outcome | 130 | –0.272 | 0.000004 |

| Pair of Variables | Number of Variables (n) | Tau Kendall (τ) | Significance Level (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| incubation time, h vs. concentration, wt% | 21 | –0.063 | 0.689 |

| incubation time, h vs. outcome | 25 | –0.267 | 0.061 |

| concentration, wt% vs. outcome | 21 | –0.241 | 0.127 |

| Author, Year | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | D6 | D7 | D8 | D9 | D10 | D11 | D12 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acosta-Torres, 2012 [34] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| Arf, 2024 [35] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| De Matteis, 2019 [36] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Fan, 2011 [37] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Gad, 2022 [38] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Low |

| Gligorijevic, 2017 [39] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | High |

| Ismaeil, 2023 [40] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| Nam, 2012 [41] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Li, 2016 [42] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| Anaraki, 2017 [43] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Peter, 2023 [44] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| Mukai, 2023 [33] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Palaskar, 2024 [45] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Low |

| Pinheiro, 2021 [46] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| Sato, 2018 [47] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| Sonkol, 2024 [48] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | High |

| Souza Neto, 2018 [49] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| Suganya, 2014 [50] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | High |

| Sun, 2021 [51] | 2 | 1 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| Thabet, 2022 [52] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Vaiyshnavi, 2022 [53] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

| Wady, 2012 [54] | 2 | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | Moderate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galant, K.; Podziewska, M.; Chęciński, M.; Chęcińska, K.; Turosz, N.; Chlubek, D.; Korcz, T.; Sikora, M. The Effect of Silver Nanoparticle Addition on the Antimicrobial Properties of Poly(methyl methacrylate) Used for Fabrication of Dental Appliances: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311633

Galant K, Podziewska M, Chęciński M, Chęcińska K, Turosz N, Chlubek D, Korcz T, Sikora M. The Effect of Silver Nanoparticle Addition on the Antimicrobial Properties of Poly(methyl methacrylate) Used for Fabrication of Dental Appliances: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311633

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalant, Kacper, Maja Podziewska, Maciej Chęciński, Kamila Chęcińska, Natalia Turosz, Dariusz Chlubek, Tomasz Korcz, and Maciej Sikora. 2025. "The Effect of Silver Nanoparticle Addition on the Antimicrobial Properties of Poly(methyl methacrylate) Used for Fabrication of Dental Appliances: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311633

APA StyleGalant, K., Podziewska, M., Chęciński, M., Chęcińska, K., Turosz, N., Chlubek, D., Korcz, T., & Sikora, M. (2025). The Effect of Silver Nanoparticle Addition on the Antimicrobial Properties of Poly(methyl methacrylate) Used for Fabrication of Dental Appliances: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11633. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311633