The Complete Plastome of ‘Mejhoul’ Date Palm: Genomic Markers and Varietal Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

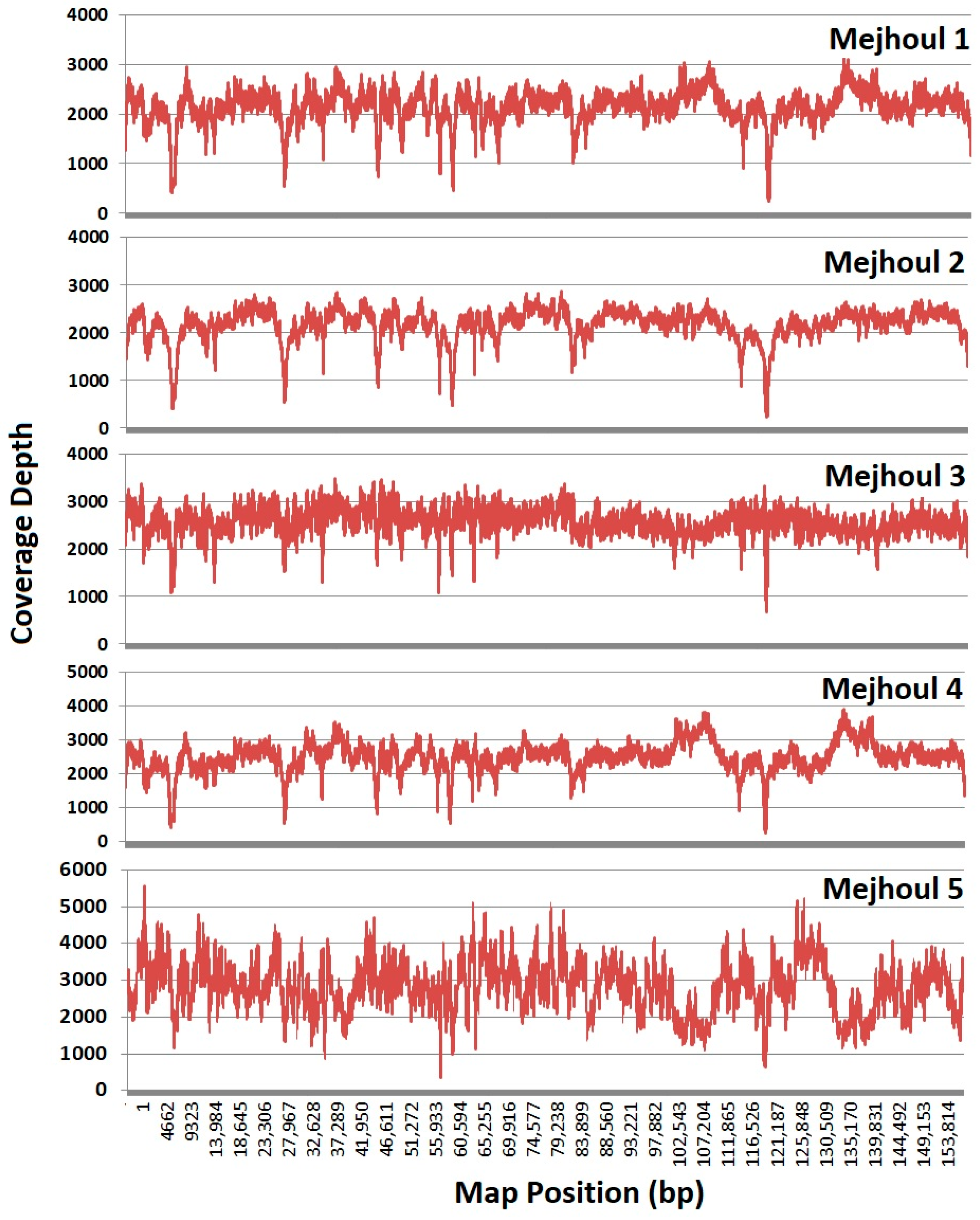

4.2. NGS and Assembly

4.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ISSR | inter-simple sequence repeat |

| NGS | next-generation sequencing |

| AFLP | fragment length polymorphism |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| SRA | short read archives |

| RAPD | random amplified polymorphic DNA |

| SNP | single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| UPGMA | unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean |

| InDel | insertion–deletion |

References

- Gros-Balthazard, M.; Hazzouri, K.M.; Flowers, J.M. Genomic insights into date palm origins. Genes 2018, 9, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, A.A. Biodiversity of date palm. Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems. In Land Use, Land Cover and Soil Sciences; Developed under the Auspices of the UNESCO, Eolss Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2011; 31p. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Orf, S.; Ahmed, M.H.; Al-Atwai, N.; Al-Zaidi, H.; Dehwah, A.; Dehwah, S. Review: Nutritional properties and benefits of the date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Bull. Natl. Nutr. Inst. Arab. Repub. Egypt 2012, 39, 98–129. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R.R. Date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) biology and utilization. In The Date Palm Genome, Vol. 1: Phylogeny, Biodiversity and Mapping; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shahib, W.; Marshall, R.J. The fruit of the date palm: Its possible use as the best food for the future? Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2003, 54, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.F.; Abdul-Wahid, A.H.; Abass, K.I. Metaxenic effect in date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) fruit in relation to level of endogenous auxins. Adv. Agric. Bot. 2014, 6, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, K.M. The role of date palm tree in improvement of the environment. Acta Hortic. 2010, 882, 777–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manickavasagan, A.; Essa, M.M.; Sukumar, E. (Eds.) Dates: Production, Processing, Food, and Medicinal Values; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Świąder, K.; Białek, K.; Hosoglu, I. Varieties of date palm fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.), their characteristics and cultivation. Postępy Tech. Przetwórstwa Spożywczego 2020, 1, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- Jonoobi, M.; Shafie, M.; Shirmohammadli, Y.; Ashori, A.; Hosseinabadi, H.Z.; Mekonnen, T. A review on date palm tree: Properties, characterization and its potential applications. J. Renew. Mater. 2019, 7, 1055–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karmadi, A.; Okoh, A.I. An Overview of Date (Phoenix dactylifera) Fruits as an Important Global Food Resource. Foods 2024, 13, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaid, A.; Oihabi, A.; Dowling, K. Mejhoul Variety: The Jewel of Dates; Khalifa International Award for Date Palm and Agricultural Innovation: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan Dates Association. 2025. Available online: https://web.facebook.com/jodates.org (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Haddad, A. The actual and future of the production and marketing of Jordanian dates. Acta Hortic. 2022, 1371, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A. Date Palm Cultivation; Food & Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Solangi, N.; Jatoi, M.A.; Markhand, G.S.; Abul-Soad, A.A.; Solangi, M.A.; Jatt, T.; Mirbahar, A.A.; Mirani, A.A. Optimizing tissue culture protocol for in vitro shoot and root development and acclimatization of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) plantlets. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2022, 64, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, K.D.; Alharbi, H.A.; Yaish, M.W.; Ahmed, I.; Alharbi, S.A.; Alotaibi, F.; Kuzyakov, Y. Date palm cultivation: A review of soil and environmental conditions and future challenges. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 2431–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadder, M.T.; Al-Antary, T.M.; Al-Rawahi, F.G. Genetic diversity of three populations of dubas bugs Ommatissus lybicus de Bergevin (tropiduchidue: Homoptera). Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2019, 28, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahimi, M.; Brhadda, N.; Ziri, R.; Fokar, M.; Amghar, I.; Gaboun, F.; Habach, A.; Meziani, R.; Elfadile, J.; Abdelwahd, R.; et al. Molecular Identification of Genetic Diversity and Population Structure in Moroccan Male Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Using Inter-Simple Sequence Repeat, Direct Amplification of Minisatellite DNA, and Simple Sequence Repeat Markers. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Feyissa, T.; Tesfaye, K.; Farrakh, S. Genetic diversity and population structure of date palms (Phoenix dactylifera L.) in Ethiopia using microsatellite markers. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dous, E.K.; George, B.; Al-Mahmoud, M.E.; Al-Jaber, M.Y.; Wang, H.; Salameh, Y.M.; Al-Azwani, E.K.; Chaluvadi, S.; Pontaroli, A.C.; DeBarry, J.; et al. De novo genome sequencing and comparative genomics of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera). Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzouri, K.M.; Flowers, J.M.; Visser, H.J.; Khierallah, H.S.M.; Rosas, U.; Pham, G.M.; Meyer, R.S.; Johansen, C.K.; Fresquez, Z.A.; Masmoudi, K.; et al. Whole genome re-sequencing of date palms yields insights into diversification of a fruit tree crop. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehdi-Azouzi, S.; Cherif, E.; Moussouni, S.; Gros-Balthazard, M.; Abbas Naqvi, S.; Ludeña, B.; Castillo, K.; Chabrillange, N.; Bouguedoura, N.; Bennaceur, M.; et al. Genetic structure of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) in the Old World reveals a strong differentiation between eastern and western populations. Ann. Bot. 2015, 116, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhoumaizi, M.A.; Devanand, P.S.; Fang, J.; Chao, C.C.T. Confirmation of ‘Medjool’date as a landrace variety through genetic analysis of ‘Medjool’accessions in Morocco. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2006, 131, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devanand, P.S.; Chao, C.T. Genetic variation within ‘Medjool’ and ‘Deglet Noor’date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) cultivars in California detected by fluorescent-AFLP markers. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2003, 78, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käfer, J.; de Boer, H.J.; Mousset, S.; Kool, A.; Dufaÿ, M.; Marais, G.A. Dioecy is associated with higher diversification rates in flowering plants. J. Evol. Biol. 2014, 27, 1478–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S.; Burkhardt, A.; Bernasconi, G. Genetic variation among females affects paternity in a dioecious plant. Oikos 2008, 117, 1594–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masmoudi-Allouche, F.; Châari-Rkhis, A.; Kriaâ, W.; Gargouri-Bouzid, R.; Jain, S.M.; Drira, N. In vitro hermaphrodism induction in date palm female flower. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.T.; Krueger, R.R. The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.): Overview of biology, uses, and cultivation. HortScience 2007, 42, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreveld, W.H. Date Palm Products; FAO Agricultural Services Bulletin No. 101; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1993; ISBN 92-5-103251-3. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/t0681e/t0681e00.htm (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Delph, L.F.; Wolf, D.E. Evolutionary consequences of gender plasticity in genetically dimorphic breeding systems. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

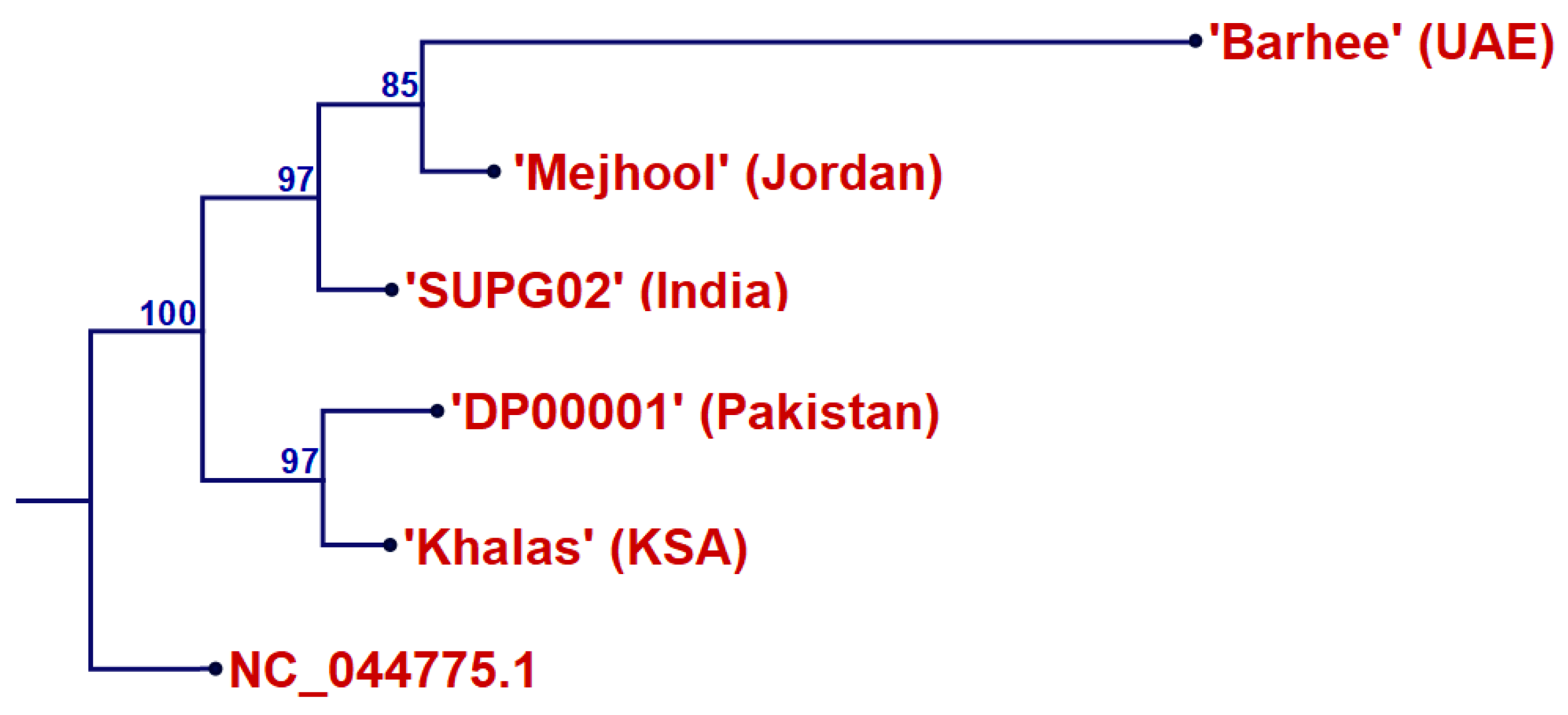

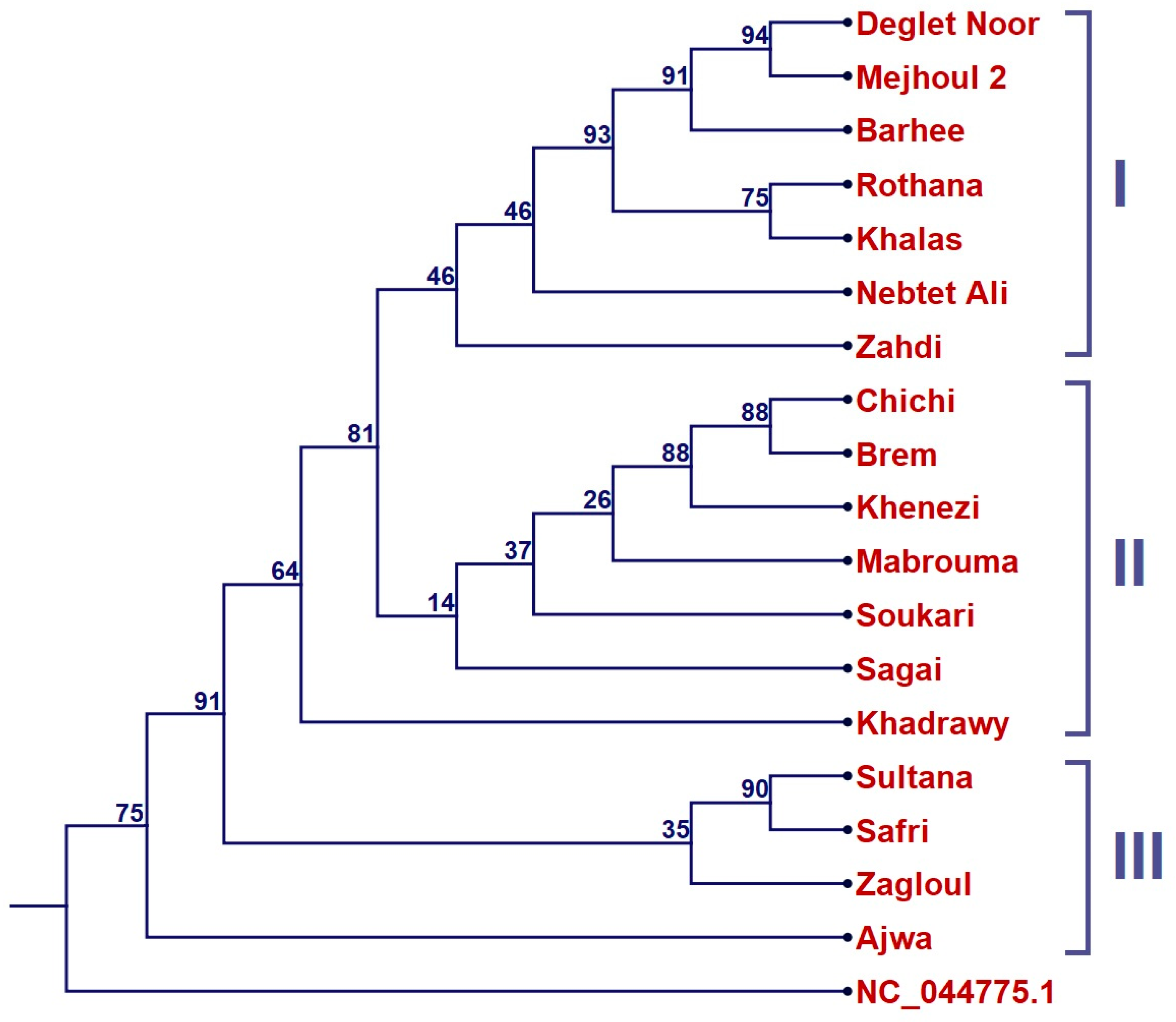

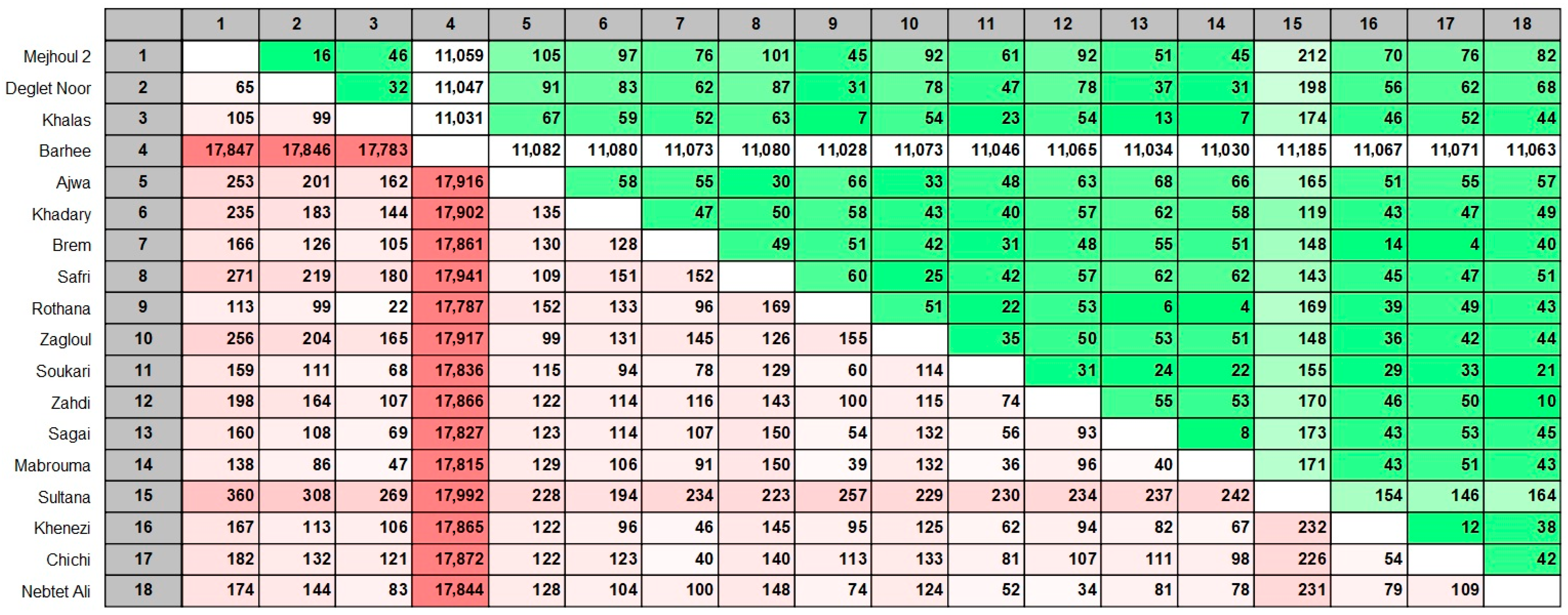

- Sabir, J.S.; Arasappan, D.; Bahieldin, A.; Abo-Aba, S.; Bafeel, S.; Zari, T.A.; Edris, S.; Shokry, A.M.; Gadalla, N.O.; Ramadan, A.M.; et al. Whole mitochondrial and plastid genome SNP analysis of nine date palm cultivars reveals plastid heteroplasmy and close phylogenetic relationships among cultivars. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, M.; Gamal, O. Investigation on molecular phylogeny of some date palm (Phoenix dactylifra L.) cultivars by protein, RAPD and ISSR markers in Saudi Arabia. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2010, 4, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- El-Khishin, D.A.; Adawy, S.S.; Hussein, E.H.; El-Itriby, H.A. AFLP fingerprinting of some Egyptian date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) cultivars. Arab. J. Biotech. 2003, 6, 223–234. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahimi, M.; Brhadda, N.; Ziri, R.; Fokar, M.; Iraqi, D.; Gaboun, F.; Diria, G. Analysis of genetic diversity and population structure of Moroccan date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) using SSR and DAMD molecular markers. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2023, 21, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mssallem, I.S.; Hu, S.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Q.; Liu, W.; Tan, J.; Yu, X.; Liu, J.; Pan, L.; Zhang, T.; et al. Genome sequence of the date palm Phoenix dactylifera L. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2274. [Google Scholar]

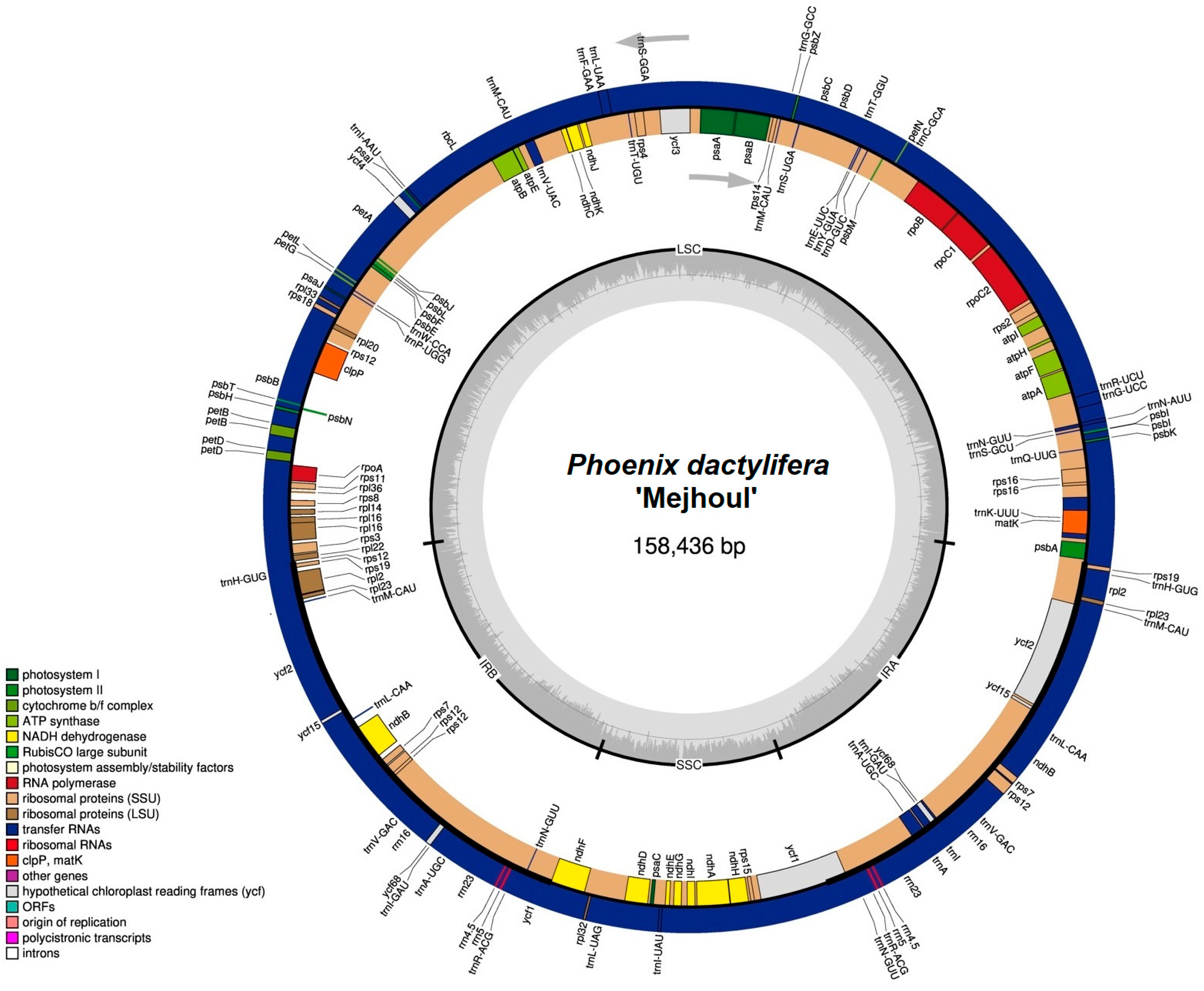

- Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Yin, Y.; Chen, K.; Yun, Q.; Zhao, D.; Al-Mssallem, I.S.; Yu, J. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.). PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, S.; Lehwark, P.; Bock, R. Organellar Genome DRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: Expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W59–W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCBI. 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Hazzouri, K.M.; Gros-Balthazard, M.; Flowers, J.M.; Copetti, D.; Lemansour, A.; Lebrun, M.; Masmoudi, K.; Ferrand, S.; Dhar, M.I.; Fresquez, Z.A.; et al. Genome-wide association mapping of date palm fruit traits. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felsenstein, J. PHYLIP (Phylogeny Inference Package); Version 3.6; Distributed by the author; Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 1981, 17, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Map | Sequence | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Map | Sequence | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Map | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | A | A | A | A | A | A | T | 3916 | tRNA-UUU | - | - | A | - | - | - | - | - | 61,398 | tRNA-AAU | A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 84,439 | RPL16 |

| A | A | A | A | A | A | A | T | 3921 | tRNA-UUU | T | T | T | T | T | C | C | C | 65,544 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 84,442 | RPL16 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | G | 3925 | tRNA-UUU | A | A | A | A | A | C | C | C | 65,546 | Intergenic | G | G | G | G | G | T | G | G | 104,863 | rRNA16 |

| A | A | A | A | A | A | A | T | 3939 | tRNA-UUU | G | G | G | G | G | T | T | T | 65,549 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | C | A | A | 104,867 | rRNA16 |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | T | 3953 | tRNA-UUU | C | C | C | C | C | T | T | T | 65,550 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | A | T | T | 104,896 | rRNA16 |

| A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 4841 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | G | G | G | 65,551 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | C | T | T | 104,873 | rRNA16 |

| A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 4845 | Intergenic | C | C | C | C | C | T | T | T | 65,552 | Intergenic | C | C | C | C | C | T | C | C | 104,876 | rRNA16 |

| A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 4848 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | T | T | T | 65,554 | Intergenic | G | G | G | G | G | C | G | G | 104,878 | rRNA16 |

| A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 4849 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | G | G | G | 65,555 | Intergenic | G | G | G | G | G | C | G | G | 104,879 | rRNA16 |

| G | G | G | G | G | T | G | G | 4856 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | A | A | A | 65,556 | Intergenic | C | C | C | C | C | T | C | C | 104,881 | rRNA16 |

| T | T | T | T | T | - | - | - | 4870 | Intergenic | C | C | C | C | C | T | T | T | 65,557 | Intergenic | G | G | G | G | G | A | G | G | 120,387 | Intergenic |

| T | T | T | T | T | - | - | - | 4871 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | T | T | T | 65,558 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 120,391 | Intergenic |

| T | - | T | - | T | - | - | - | 4872 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | G | G | G | 65,560 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | A | T | T | 120,392 | Intergenic |

| - | - | - | - | - | A | A | A | 9220 | Intergenic | C | C | C | C | C | A | A | A | 65,561 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | A | T | T | 120,393 | Intergenic |

| - | - | - | - | - | T | T | T | 9221 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | G | G | G | 65,562 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | G | A | A | 120,395 | Intergenic |

| G | G | G | G | G | A | G | G | 9225 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | C | C | C | 65,563 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | C | T | T | 120,397 | Intergenic |

| C | C | C | C | C | T | C | C | 9228 | Intergenic | G | G | G | G | G | T | T | T | 65,566 | Intergenic | C | C | C | C | C | A | C | C | 120,398 | Intergenic |

| C | C | C | C | C | A | A | C | 9251 | Intergenic | G | G | G | G | G | A | A | A | 65,568 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | G | A | A | 120,400 | Intergenic |

| T | T | T | T | T | A | A | T | 9254 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | T | T | - | 69,867 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | - | T | T | 120,404 | Intergenic |

| T | T | T | T | T | A | A | T | 9261 | Intergenic | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | T | 69,870 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 120,409 | Intergenic |

| T | T | T | T | T | A | A | T | 9263 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | T | T | G | 69,871 | Intergenic | G | G | G | G | G | T | A | T | 120,424 | Intergenic |

| T | T | T | T | T | A | A | T | 9264 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | T | 69,874 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | A | - | - | 120,453 | tRNA-UAU |

| T | T | T | T | T | A | A | T | 9269 | Intergenic | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | T | 69,875 | Intergenic | - | - | - | - | - | - | T | - | 120,719 | Intergenic |

| T | T | T | T | T | A | A | A | 9286 | Intergenic | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | G | 69,878 | Intergenic | G | G | G | G | G | T | G | G | 130,157 | Ycf1 |

| T | T | T | T | T | A | T | T | 9288 | Intergenic | C | C | C | C | C | C | C | T | 69,890 | Intergenic | A | A | A | A | A | A | T | T | 134,605 | rRNA23 |

| C | C | C | C | C | C | A | C | 9289 | Intergenic | T | T | T | T | T | T | A | T | 83,890 | Intergenic | G | G | G | G | G | G | C | C | 134,608 | rRNA23 |

| A | A | A | A | A | C | A | A | 47,238 | Intergenic | A | A | - | A | A | C | C | C | 84,413 | RPL16 | C | C | C | C | C | C | T | T | 134,609 | rRNA23 |

| - | - | - | - | - | C | - | - | 47,257 | Intergenic | T | T | - | T | T | T | T | T | 84,414 | RPL16 | T | T | T | T | T | T | A | A | 134,610 | rRNA23 |

| T | T | T | T | T | C | T | T | 47,259 | Intergenic | T | T | - | T | T | T | T | T | 84,415 | RPL16 | A | A | A | A | A | A | G | G | 134,613 | rRNA23 |

| G | G | G | G | G | A | G | G | 47,260 | Intergenic | T | T | - | T | T | T | T | T | 84,416 | RPL16 | A | A | A | A | A | A | G | G | 134,614 | rRNA23 |

| A | A | A | A | A | C | A | A | 47,281 | Intergenic | T | T | - | T | T | T | T | A | 84,417 | RPL16 | C | C | C | C | C | C | T | T | 134,619 | rRNA23 |

| C | C | C | C | C | T | C | C | 47,367 | Intergenic | T | T | - | T | T | T | T | T | 84,418 | RPL16 | G | G | G | G | G | G | A | A | 134,625 | rRNA23 |

| A | A | A | A | A | A | T | A | 47,398 | Intergenic | T | T | - | T | T | T | T | A | 84,419 | RPL16 | C | C | C | C | C | C | T | T | 134,626 | rRNA23 |

| - | - | - | - | - | A | A | A | 47,410 | Intergenic | T | T | A | T | T | T | T | T | 84,420 | RPL16 | C | C | C | C | C | C | A | A | 134,632 | rRNA23 |

| - | - | - | - | - | T | T | T | 47,411 | Intergenic | - | - | T | - | - | T | T | T | 84,421 | RPL16 | G | G | G | G | G | A | G | G | 139,767 | rRNA16 |

| A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 47,419 | Intergenic | - | - | T | - | - | T | T | T | 84,422 | RPL16 | C | C | C | C | C | G | C | C | 139,769 | rRNA16 |

| C | C | C | C | A | A | C | C | 58,969 | Intergenic | - | - | T | - | - | T | T | T | 84,423 | RPL16 | C | C | C | C | C | G | C | C | 139,770 | rRNA16 |

| C | C | C | C | - | C | A | C | 58,970 | Intergenic | - | - | T | - | - | T | T | T | 84,424 | RPL16 | G | G | G | G | G | A | G | G | 139,772 | rRNA16 |

| - | - | - | - | - | A | - | - | 58,980 | Intergenic | - | - | T | - | - | T | T | T | 84,425 | RPL16 | A | A | A | A | A | G | A | A | 139,775 | rRNA16 |

| C | T | C | C | T | T | T | T | 61,317 | tRNA-AAU | - | - | T | - | - | T | T | T | 84,426 | RPL16 | A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 139,779 | rRNA16 |

| A | T | A | A | A | T | T | T | 61,386 | tRNA-AAU | - | - | T | - | - | T | T | T | 84,427 | RPL16 | T | T | T | T | T | G | T | T | 139,781 | rRNA16 |

| A | A | T | A | A | A | A | A | 61,391 | tRNA-AAU | A | A | A | A | A | T | A | A | 84,437 | RPL16 | C | C | C | C | C | A | C | C | 139,785 | rRNA16 |

| ‘Mejhoul’ 1–8 | ‘Barhee’ & ‘Khalas’ | Map | ‘Mejhoul’ 1–8 | ‘Barhee’ & ‘Khalas’ | Map | ‘Mejhoul’ 1–8 | ‘Barhee’ & ‘Khalas’ | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | 17 | - | A | 14,785 | - | A | 64,985 |

| T | A | 112 | - | A | 14,786 | C | G | 66,944 |

| A | G | 152 | - | T | 14,787 | T | C | 67,889 |

| G | A | 1433 | T | C | 20,212 | T | G | 69,478 |

| T | - | 3842 | C | T | 22,579 | C | A | 70,574 |

| T | C | 4741 | T | C | 24,138 | T | - | 72,593 |

| A | G | 5038 | - | A | 29,890 | T | - | 72,857 |

| A | G | 7164 | - | T | 31,439 | G | A | 73,745 |

| T | - | 7451 | - | A | 33,299 | G | A | 75,080 |

| A | G | 8279 | C | A | 35,903 | T | - | 77,603 |

| G | T | 9094 | C | T | 36,168 | G | T | 83,409 |

| - | T | 13,895 | A | - | 60,920 | A | C | 83,410 |

| C | A | 14,621 | - | A | 64,981 | T | C | 84,422 |

| - | T | 14,645 | - | A | 64,982 | - | T | 84,831 |

| - | A | 14,783 | - | T | 64,983 | - | T | 86,227 |

| - | T | 14,784 | - | G | 64,984 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sadder, M.T.; Alashoush, A.; Alsmairat, N.; Haddad, A. The Complete Plastome of ‘Mejhoul’ Date Palm: Genomic Markers and Varietal Identification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311603

Sadder MT, Alashoush A, Alsmairat N, Haddad A. The Complete Plastome of ‘Mejhoul’ Date Palm: Genomic Markers and Varietal Identification. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311603

Chicago/Turabian StyleSadder, Monther T., Anfal Alashoush, Nihad Alsmairat, and Anwar Haddad. 2025. "The Complete Plastome of ‘Mejhoul’ Date Palm: Genomic Markers and Varietal Identification" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311603

APA StyleSadder, M. T., Alashoush, A., Alsmairat, N., & Haddad, A. (2025). The Complete Plastome of ‘Mejhoul’ Date Palm: Genomic Markers and Varietal Identification. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311603