Lytic or Latent Phase in Human Cytomegalovirus Infection: An Epigenetic Trigger

Abstract

1. Introduction

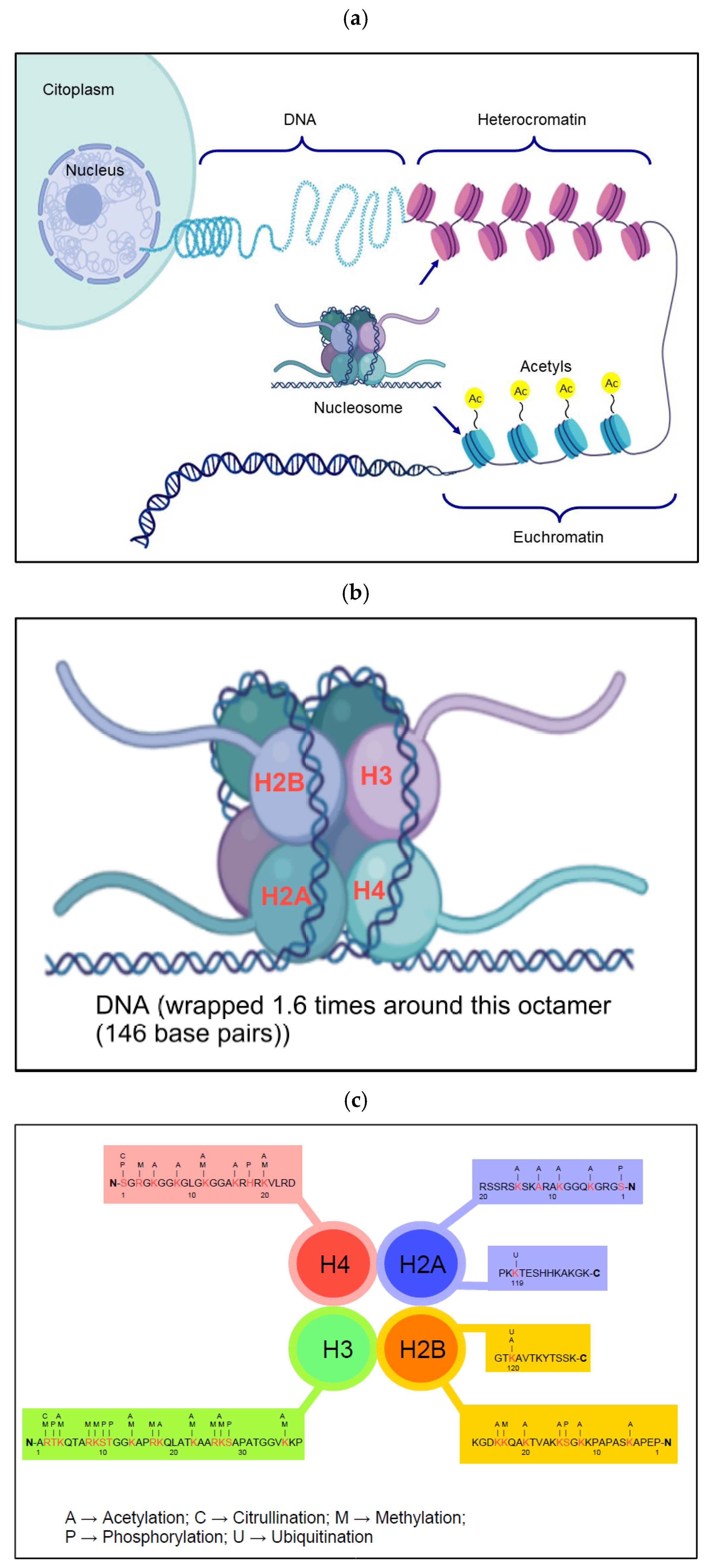

2. An Overview of Epigenetics

3. Biological Events That Occur During an Infection

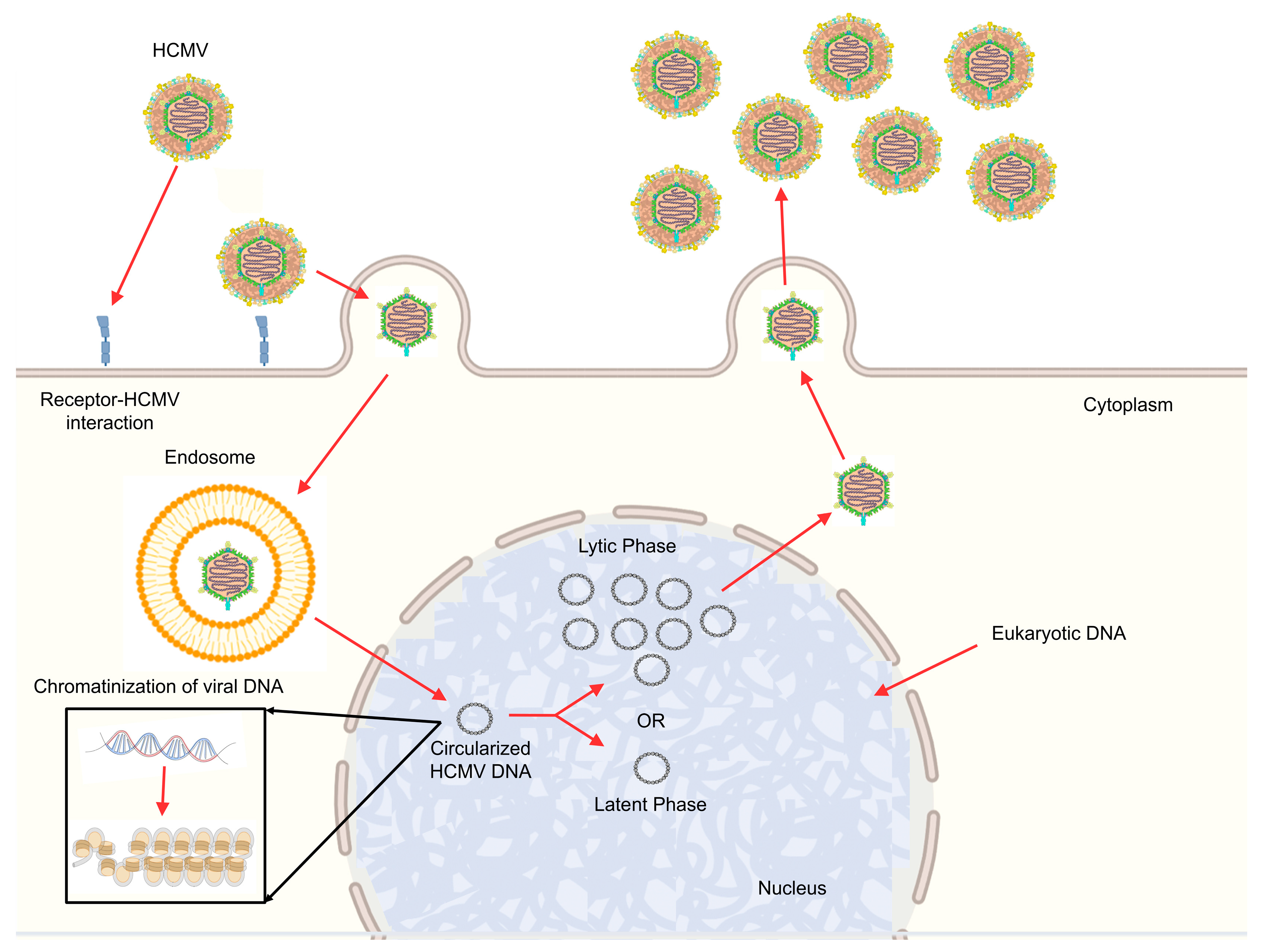

4. Human Cytomegalovirus: General Characteristics

5. HCMV Lifecycle

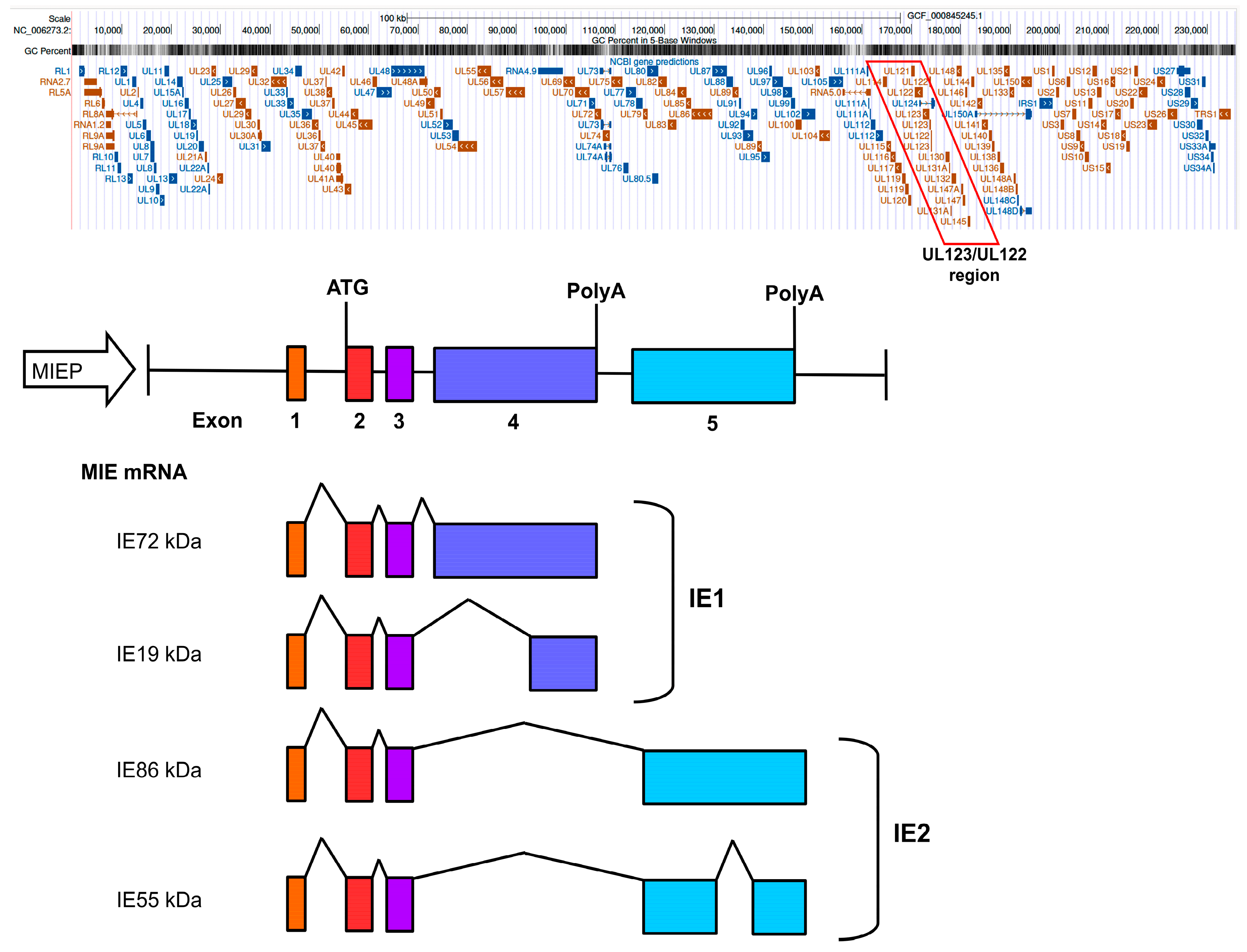

HCMV Lifecycle: Gene Regulatory Network in the Lytic Phase

6. Chromatinization of HCMV Genome

6.1. Anchoring Sites of Viral Genomes to Host Chromosomes

6.2. Nucleosome Formation in HCMV DNA as a Cellular Repressor Mechanism

7. Overcoming Repression of the HCMV Genome

8. Reversibility of the HCMV Genome from the Latent to the Lytic State

8.1. Latent Infection (Constitutive Heterochromatin)

8.2. Latent Infection (Facultative Chromatin)

8.3. Lytic Replication and Reactivation

9. Future Prospects: Epigenetic Reprogramming of Viruses

Lytic Phase Reactivation and Latent Phase Blocking

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lucic, B.; de Castro, I.J.; Lusic, M. Viruses in the Nucleus. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2021, 13, a039446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milavetz, B.I.; Balakrishnan, L. Viral epigenetics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1238, 569–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soderberg-Naucler, C.; Fish, K.N.; Nelson, J.A. Growth of human cytomegalovirus in primary macrophages. Methods 1998, 16, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, M.; Monard, S.; Sissons, P.; Sinclair, J. Detection of endogenous human cytomegalovirus in CD34+ bone marrow progenitors. J. Gen. Virol. 1996, 77 Pt 12, 3099–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozman, B.; Nachshon, A.; Levi Samia, R.; Lavi, M.; Schwartz, M.; Stern-Ginossar, N. Temporal dynamics of HCMV gene expression in lytic and latent infections. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, M.B. Chromatin-mediated regulation of cytomegalovirus gene expression. Virus Res. 2011, 157, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, C.C.; Tarrant-Elorza, M.; Pari, G.S. Cis and trans acting factors involved in human cytomegalovirus experimental and natural latent infection of CD14 (+) monocytes and CD34 (+) cells. PLoS. Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, L.B.; Diggins, N.L.; Caposio, P.; Hancock, M.H. Advances in Model Systems for Human Cytomegalovirus Latency and Reactivation. mBio 2022, 13, e0172421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehme, Z.; Pasquereau, S.; Herbein, G. Control of viral infections by epigenetic-targeted therapy. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B.A.; Wills, M.R.; Sinclair, J.H. Advances in the treatment of cytomegalovirus. Br. Med. Bull. 2019, 131, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, I.J.; Jackson, S.E.; Poole, E.L.; Nachshon, A.; Rozman, B.; Schwartz, M.; Prinjha, R.K.; Tough, D.F.; Sinclair, J.H.; Wills, M.R. Bromodomain proteins regulate human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation allowing epigenetic therapeutic intervention. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023025118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, I.J.; Sinclair, J.H.; Wills, M.R. Bromodomain Inhibitors as Therapeutics for Herpesvirus-Related Disease: All BETs Are Off? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franci, G.; Miceli, M.; Altucci, L. Targeting epigenetic networks with polypharmacology: A new avenue to tackle cancer. Epigenomics 2010, 2, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Schubeler, D. Genomic patterns of DNA methylation: Targets and function of an epigenetic mark. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2007, 19, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkowska, R.Z.; Jurkowski, T.P.; Jeltsch, A. Structure and function of mammalian DNA methyltransferases. Chembiochem 2011, 12, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Tuorto, F.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Liebers, R.; Zhang, L.; Qu, Y.; Qian, J.; et al. Dnmt2 mediates intergenerational transmission of paternally acquired metabolic disorders through sperm small non-coding RNAs. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbert, P.B.; Ahmad, K.; Almouzni, G.; Ausio, J.; Berger, F.; Bhalla, P.L.; Bonner, W.M.; Cande, W.Z.; Chadwick, B.P.; Chan, S.W.; et al. A unified phylogeny-based nomenclature for histone variants. Epigenet. Chromatin 2012, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipescu, D.; Szenker, E.; Almouzni, G. Developmental roles of histone H3 variants and their chaperones. Trends Genet. 2013, 29, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacAlpine, D.M.; Almouzni, G. Chromatin and DNA replication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a010207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisner, R.M.; Madhani, H.D. Patterning chromatin: Form and function for H2A.Z variant nucleosomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2006, 16, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, L.; Milavetz, B. Histone hyperacetylation in the coding region of chromatin undergoing transcription in SV40 minichromosomes is a dynamic process regulated directly by the presence of RNA polymerase II. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 365, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, Y. Histone acetylases--versatile players. Genes Cells 2001, 6, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapira, M. Structural biology of human metal-dependent histone deacetylases. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2011, 206, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordo, D. Structure and evolution of human sirtuins. Curr. Drug Targets 2013, 14, 662–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, F.; Jin, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Lv, X.; Ren, L.; Yang, J.; Chen, D.; Wang, B.; Yang, W.; Chen, L.; et al. HDAC11 promotes both NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD and caspase-3/GSDME pathways causing pyroptosis via ERG in vascular endothelial cells. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.C.; Van Rechem, C.; Whetstine, J.R. Histone lysine methylation dynamics: Establishment, regulation, and biological impact. Mol. Cell 2012, 48, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallestad, L.; Woods, E.; Christensen, K.; Gefroh, A.; Balakrishnan, L.; Milavetz, B. Transcription and replication result in distinct epigenetic marks following repression of early gene expression. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milavetz, B.; Kallestad, L.; Gefroh, A.; Adams, N.; Woods, E.; Balakrishnan, L. Virion-mediated transfer of SV40 epigenetic information. Epigenetics 2012, 7, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempera, I.; Lieberman, P.M. Chromatin organization of gammaherpesvirus latent genomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1799, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.T.S. Mechanistic Perspectives on Herpes Simplex Virus Inhibition by Phenolic Acids and Tannins: Interference with the Herpesvirus Life Cycle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaeffer-Yosef, T.; Nesher, L. Tackling CMV in Transplant Recipients: Past, Present, and Future. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2025, 14, 1183–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Media, T.S.; Cano-Aroca, L.; Tagawa, T. Non-Coding RNAs and Immune Evasion in Human Gamma-Herpesviruses. Viruses 2025, 17, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.B., Jr. The ‘indirect’ effects of cytomegalovirus infection. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9, 2453–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleiss, M.R. Cytomegalovirus in the neonate: Immune correlates of infection and protection. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 501801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, K.; Mucha, J.; Neumann, M.; Lewandowski, W.; Kaczanowska, M.; Grys, M.; Schmidt, E.; Natenshon, A.; Talarico, C.; Buck, P.O.; et al. A systematic literature review of the global seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus: Possible implications for treatment, screening, and vaccine development. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guermouche, H.; Burrel, S.; Mercier-Darty, M.; Kofman, T.; Rogier, O.; Pawlotsky, J.M.; Boutolleau, D.; Rodriguez, C. Characterization of the dynamics of human cytomegalovirus resistance to antiviral drugs by ultra-deep sequencing. Antivir. Res. 2020, 173, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N. Late-onset cytomegalovirus disease as a significant complication in solid organ transplant recipients receiving antiviral prophylaxis: A call to heed the mounting evidence. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grose, C.; Weiner, C.P. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Two decades later. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 163, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K.B.; Stagno, S.; Pass, R.F.; Britt, W.J.; Boll, T.J.; Alford, C.A. The outcome of congenital cytomegalovirus infection in relation to maternal antibody status. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 326, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeran, M.C.; Lokensgard, J.R.; Schleiss, M.R. Neuropathogenesis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Disease mechanisms and prospects for intervention. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinzger, C.; Digel, M.; Jahn, G. Cytomegalovirus cell tropism. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 325, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.A.; Lloyd, M.L. A Review of Murine Cytomegalovirus as a Model for Human Cytomegalovirus Disease-Do Mice Lie? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, C.K.; Shakya, A.K.; Lee, B.J.; Streblow, D.N.; Caposio, P.; Yurochko, A.D. The Differentiation of Human Cytomegalovirus Infected-Monocytes Is Required for Viral Replication. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.A.; Chan, G.C.; O’Connor, C.M. Modulation of host cell signaling during cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, G.; Nogalski, M.T.; Stevenson, E.V.; Yurochko, A.D. Human cytomegalovirus induction of a unique signalsome during viral entry into monocytes mediates distinct functional changes: A strategy for viral dissemination. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012, 92, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendland, K.; Thielke, M.; Meisel, A.; Mergenthaler, P. Intrinsic hypoxia sensitivity of the cytomegalovirus promoter. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooley, A.L.; O’Connor, C.M. Regulation of the MIE Locus During HCMV Latency and Reactivation. Pathogens 2020, 9, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, S.; Isler, J.A.; Alwine, J.C. Analysis of splice variants of the immediate-early 1 region of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 8191–8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, J.A.; Bresnahan, W.A.; Shenk, T.E. Construction of a rationally designed human cytomegalovirus variant encoding a temperature-sensitive immediate-early 2 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 3141–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaves, R.F.; Mocarski, E.S. Defective growth correlates with reduced accumulation of a viral DNA replication protein after low-multiplicity infection by a human cytomegalovirus ie1 mutant. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.L.; Keller, M.J.; McCoy, J.J. Requirement of multiple cis-acting elements in the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early distal enhancer for viral gene expression and replication. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isomura, H.; Tsurumi, T.; Stinski, M.F. Role of the proximal enhancer of the major immediate-early promoter in human cytomegalovirus replication. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 12788–12799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.L.; Pruessner, J.A. The human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early distal enhancer region is required for efficient viral replication and immediate-early gene expression. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 1602–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R.; Groves, I.J.; Wills, M.R.; Sinclair, J.H.; Reeves, M.B. Human cytomegalovirus major immediate early transcripts arise predominantly from the canonical major immediate early promoter in reactivating progenitor-derived dendritic cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2020, 101, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-McMillen, D.; Rak, M.; Buehler, J.C.; Igarashi-Hayes, S.; Kamil, J.P.; Moorman, N.J.; Goodrum, F. Alternative promoters drive human cytomegalovirus reactivation from latency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 17492–17497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, B.A.; Humby, M.S.; Miller, W.E.; O’Connor, C.M. Human cytomegalovirus G protein-coupled receptor US28 promotes latency by attenuating c-fos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, C.B.; Li, M.; Parida, M.; Hu, Q.; Ince, D.; Collins, G.S.; Meier, J.L.; Price, D.H. Human Cytomegalovirus IE2 Both Activates and Represses Initiation and Modulates Elongation in a Context-Dependent Manner. mBio 2022, 13, e0033722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ball, C.B.; Collins, G.; Hu, Q.; Luse, D.S.; Price, D.H.; Meier, J.L. Human cytomegalovirus IE2 drives transcription initiation from a select subset of late infection viral promoters by host RNA polymerase II. PLoS. Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, R.L.; Clark, C.L.; Morello, C.S.; Spector, D.H. Development of cell lines that provide tightly controlled temporal translation of the human cytomegalovirus IE2 proteins for complementation and functional analyses of growth-impaired and nonviable IE2 mutant viruses. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 7059–7077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.; Chou, C.; Li, H.; Hai, R.; Patterson, D.; Stolc, V.; Zhu, H.; Liu, F. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 14223–14228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, M.; Murphy, J.; Greaves, R.; Fairley, J.; Brehm, A.; Sinclair, J. Autorepression of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early promoter/enhancer at late times of infection is mediated by the recruitment of chromatin remodeling enzymes by IE86. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 9998–10009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrington, J.M.; Khoury, E.L.; Mocarski, E.S. Human cytomegalovirus ie2 negatively regulates alpha gene expression via a short target sequence near the transcription start site. J. Virol. 1991, 65, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shnayder, M.; Nachshon, A.; Krishna, B.; Poole, E.; Boshkov, A.; Binyamin, A.; Maza, I.; Sinclair, J.; Schwartz, M.; Stern-Ginossar, N. Defining the Transcriptional Landscape during Cytomegalovirus Latency with Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. mBio 2018, 9, e00013-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitzsche, A.; Paulus, C.; Nevels, M. Temporal dynamics of cytomegalovirus chromatin assembly in productively infected human cells. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11167–11180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Fraser, N.W. Temporal association of the herpes simplex virus genome with histone proteins during a lytic infection. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 3530–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalckvar, E.; Paulus, C.; Tillo, D.; Asbach-Nitzsche, A.; Lubling, Y.; Winterling, C.; Strieder, N.; Mucke, K.; Goodrum, F.; Segal, E.; et al. Nucleosome maps of the human cytomegalovirus genome reveal a temporal switch in chromatin organization linked to a major IE protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13126–13131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, I.J.; Reeves, M.B.; Sinclair, J.H. Lytic infection of permissive cells with human cytomegalovirus is regulated by an intrinsic ‘pre-immediate-early’ repression of viral gene expression mediated by histone post-translational modification. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 2364–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Otter, M.; Wahl, G.M. Coupling of mitotic chromosome tethering and replication competence in epstein-barr virus-based plasmids. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 3576–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Young, B.D.; Griffin, B.E. Random association of Epstein-Barr virus genomes with host cell metaphase chromosomes in Burkitt’s lymphoma-derived cell lines. J. Virol. 1985, 56, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, M.A., 2nd; Robertson, E.S. The latency-associated nuclear antigen tethers the Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genome to host chromosomes in body cavity-based lymphoma cells. Virology 1999, 264, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrant-Elorza, M.; Rossetto, C.C.; Pari, G.S. Maintenance and replication of the human cytomegalovirus genome during latency. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 16, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, L.; Gilmour, J.; Bonifer, C. The Role of the Ubiquitously Expressed Transcription Factor Sp1 in Tissue-specific Transcriptional Regulation and in Disease. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2016, 89, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yurochko, A.D.; Mayo, M.W.; Poma, E.E.; Baldwin, A.S., Jr.; Huang, E.S. Induction of the transcription factor Sp1 during human cytomegalovirus infection mediates upregulation of the p65 and p105/p50 NF-kappaB promoters. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 4638–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafemina, R.L.; Pizzorno, M.C.; Mosca, J.D.; Hayward, G.S. Expression of the acidic nuclear immediate-early protein (IE1) of human cytomegalovirus in stable cell lines and its preferential association with metaphase chromosomes. Virology 1989, 172, 584–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, G.W.; Kelly, C.; Sinclair, J.H.; Rickards, C. Disruption of PML-associated nuclear bodies mediated by the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early gene product. J. Gen. Virol. 1998, 79 Pt 5, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhardt, J.; Smith, G.B.; Himmelheber, C.T.; Azizkhan-Clifford, J.; Mocarski, E.S. The carboxyl-terminal region of human cytomegalovirus IE1491aa contains an acidic domain that plays a regulatory role and a chromatin-tethering domain that is dispensable during viral replication. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, S.; Kaps, J.; Czech, N.; Paulus, C.; Nevels, M. Physical requirements and functional consequences of complex formation between the cytomegalovirus IE1 protein and human STAT2. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 12854–12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.N.; Jeang, K.T.; Lietman, T.; Hayward, G.S. Structural Organization of the Spliced Immediate-Early Gene Complex that Encodes the Major Acidic Nuclear (IE1) and Transactivator (IE2) Proteins of African Green Monkey Cytomegalovirus. J. Biomed. Sci. 1995, 2, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauch-Mucke, K.; Schon, K.; Paulus, C.; Nevels, M.M. Evidence for Tethering of Human Cytomegalovirus Genomes to Host Chromosomes. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 577428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, S.M.; Yetming, K.D.; Paulus, C.; Nevels, M.; Kalejta, R.F. Human Cytomegalovirus Genomes Survive Mitosis via the IE19 Chromatin-Tethering Domain. mBio 2020, 11, e02410-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krude, T.; Keller, C. Chromatin assembly during S phase: Contributions from histone deposition, DNA replication and the cell division cycle. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2001, 58, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luger, K.; Mader, A.W.; Richmond, R.K.; Sargent, D.F.; Richmond, T.J. Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature 1997, 389, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucke, K.; Paulus, C.; Bernhardt, K.; Gerrer, K.; Schon, K.; Fink, A.; Sauer, E.M.; Asbach-Nitzsche, A.; Harwardt, T.; Kieninger, B.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus major immediate early 1 protein targets host chromosomes by docking to the acidic pocket on the nucleosome surface. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 1228–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Q.; Chen, P.; Wang, M.; Fang, J.; Yang, N.; Li, G.; Xu, R.M. Human cytomegalovirus IE1 protein alters the higher-order chromatin structure by targeting the acidic patch of the nucleosome. Elife 2016, 5, e11911, Erratum in Elife, 5, e15893. https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.15893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan-Zambrano, G.; Burton, A.; Bannister, A.J.; Schneider, R. Histone post-translational modifications—Cause and consequence of genome function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albright, E.R.; Kalejta, R.F. Canonical and Variant Forms of Histone H3 Are Deposited onto the Human Cytomegalovirus Genome during Lytic and Latent Infections. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 10309–10320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.W.; Elsaesser, S.J.; Noh, K.M.; Stadler, S.C.; Allis, C.D. Daxx is an H3.3-specific histone chaperone and cooperates with ATRX in replication-independent chromatin assembly at telomeres. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14075–14080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsasser, S.J.; Huang, H.; Lewis, P.W.; Chin, J.W.; Allis, C.D.; Patel, D.J. DAXX envelops a histone H3.3-H4 dimer for H3.3-specific recognition. Nature 2012, 491, 560–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhall, D.L.; Groves, I.J.; Reeves, M.B.; Wilkinson, G.; Sinclair, J.H. Human Daxx-mediated repression of human cytomegalovirus gene expression correlates with a repressive chromatin structure around the major immediate early promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 37652–37660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, T.S.; Glass, M.; Cole, J.J.; Rather, M.I.; Marsden, M.; Neilson, M.; Brock, C.; Humphreys, I.R.; Everett, R.D.; Adams, P.D. Histone chaperone HIRA deposits histone H3.3 onto foreign viral DNA and contributes to anti-viral intrinsic immunity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 11673–11683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, R.; Pandolfi, P.P. Structure, dynamics and functions of promyelocytic leukaemia nuclear bodies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalejta, R.F. Functions of human cytomegalovirus tegument proteins prior to immediate early gene expression. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 325, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, R.; Papa, A.; Pandolfi, P.P. Regulation of apoptosis by PML and the PML-NBs. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6299–6312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavalai, N.; Stamminger, T. New insights into the role of the subnuclear structure ND10 for viral infection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1783, 2207–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, R.D.; Chelbi-Alix, M.K. PML and PML nuclear bodies: Implications in antiviral defence. Biochimie 2007, 89, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan Fada, B.; Reward, E.; Gu, H. The Role of ND10 Nuclear Bodies in Herpesvirus Infection: A Frenemy for the Virus? Viruses 2021, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishov, A.M.; Vladimirova, O.V.; Maul, G.G. Daxx-mediated accumulation of human cytomegalovirus tegument protein pp71 at ND10 facilitates initiation of viral infection at these nuclear domains. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 7705–7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffert, R.T.; Penkert, R.R.; Kalejta, R.F. Cellular and viral control over the initial events of human cytomegalovirus experimental latency in CD34+ cells. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 5594–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salsman, J.; Wang, X.; Frappier, L. Nuclear body formation and PML body remodeling by the human cytomegalovirus protein UL35. Virology 2011, 414, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, M.N.; Sztul, E.; Daily, S.L.; Perry, A.L.; Frederick, S.L.; Gill, R.B.; Hartline, C.B.; Streblow, D.N.; Varnum, S.M.; Smith, R.D.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus UL97 kinase activity is required for the hyperphosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein and inhibits the formation of nuclear aggresomes. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 5054–5067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, E.L.; Kew, V.G.; Lau, J.C.H.; Murray, M.J.; Stamminger, T.; Sinclair, J.H.; Reeves, M.B. A Virally Encoded DeSUMOylase Activity Is Required for Cytomegalovirus Reactivation from Latency. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, C.; Harwardt, T.; Walter, B.; Marxreiter, A.; Zenger, M.; Reuschel, E.; Nevels, M.M. Revisiting promyelocytic leukemia protein targeting by human cytomegalovirus immediate-early protein 1. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, M.; Read, C.; Neusser, G.; Kranz, C.; Kuderna, A.K.; Muller, R.; Full, F.; Worz, S.; Reichel, A.; Schilling, E.M.; et al. Dual signaling via interferon and DNA damage response elicits entrapment by giant PML nuclear bodies. Elife 2022, 11, e73006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, E.M.; Scherer, M.; Reuter, N.; Schweininger, J.; Muller, Y.A.; Stamminger, T. The Human Cytomegalovirus IE1 Protein Antagonizes PML Nuclear Body-Mediated Intrinsic Immunity via the Inhibition of PML De Novo SUMOylation. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e02049-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.H.; Hayward, G.S. The major immediate-early proteins IE1 and IE2 of human cytomegalovirus colocalize with and disrupt PML-associated nuclear bodies at very early times in infected permissive cells. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 4599–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevels, M.; Paulus, C.; Shenk, T. Human cytomegalovirus immediate-early 1 protein facilitates viral replication by antagonizing histone deacetylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17234–17239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Bennett, C.; Shenk, T. Dynamic histone H3 acetylation and methylation at human cytomegalovirus promoters during replication in fibroblasts. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 9525–9536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, M.; Woodhall, D.; Compton, T.; Sinclair, J. Human cytomegalovirus IE72 protein interacts with the transcriptional repressor hDaxx to regulate LUNA gene expression during lytic infection. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 7185–7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, A.; Claessens, M. Disruptive membrane interactions of alpha-synuclein aggregates. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2019, 1867, 468–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeves, M.B.; Sinclair, J.H. Analysis of latent viral gene expression in natural and experimental latency models of human cytomegalovirus and its correlation with histone modifications at a latent promoter. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, L.R.; Hargett, D.; Soland, M.; Bego, M.G.; Rossetto, C.C.; Almeida-Porada, G.; St Jeor, S. HCMV protein LUNA is required for viral reactivation from latently infected primary CD14(+) cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Rao, C.M. Epigenetic tools (The Writers, The Readers and The Erasers) and their implications in cancer therapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 837, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creyghton, M.P.; Cheng, A.W.; Welstead, G.G.; Kooistra, T.; Carey, B.W.; Steine, E.J.; Hanna, J.; Lodato, M.A.; Frampton, G.M.; Sharp, P.A.; et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 21931–21936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, V.; Patel, N.; Turcotte, M.; Bosse, Y.; Pare, G.; Meyre, D. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trojer, P.; Reinberg, D. Facultative heterochromatin: Is there a distinctive molecular signature? Mol. Cell 2007, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.J.; Seto, E. The Rpd3/Hda1 family of lysine deacetylases: From bacteria and yeast to mice and men. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, D.L.; Nesburn, A.B.; Ghiasi, H.; Ong, J.; Lewis, T.L.; Lokensgard, J.R.; Wechsler, S.L. Detection of latency-related viral RNAs in trigeminal ganglia of rabbits latently infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 1987, 61, 3820–3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T.; Sugimoto, A.; Inagaki, T.; Yanagi, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Sato, Y.; Kimura, H. Molecular Basis of Epstein-Barr Virus Latency Establishment and Lytic Reactivation. Viruses 2021, 13, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fan, Z.; Shliaha, P.V.; Miele, M.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Jiang, X.; Helin, K. H3K4me3 regulates RNA polymerase II promoter-proximal pause-release. Nature 2023, 615, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Espinosa-Diez, C.; Mahan, S.; Du, M.; Nguyen, A.T.; Hahn, S.; Chakraborty, R.; Straub, A.C.; Martin, K.A.; Owens, G.K.; et al. H3K4 di-methylation governs smooth muscle lineage identity and promotes vascular homeostasis by restraining plasticity. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 2765–2782 e2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, B. Role of H3K4 monomethylation in gene regulation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2024, 84, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharda, A.; Humphrey, T.C. The role of histone H3K36me3 writers, readers and erasers in maintaining genome stability. DNA Repair. 2022, 119, 103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streubel, G.; Watson, A.; Jammula, S.G.; Scelfo, A.; Fitzpatrick, D.J.; Oliviero, G.; McCole, R.; Conway, E.; Glancy, E.; Negri, G.L.; et al. The H3K36me2 Methyltransferase Nsd1 Demarcates PRC2-Mediated H3K27me2 and H3K27me3 Domains in Embryonic Stem Cells. Mol. Cell 2018, 70, 371–379 e375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, U.T.F.; Tan, B.K.Y.; Poh, J.J.X.; Chen, E.S. Structural and functional specificity of H3K36 methylation. Epigenetics Chromatin 2022, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narbey, R.; Mouchel-Vielh, E.; Gibert, J.M. The H3K79me3 methyl-transferase Grappa is involved in the establishment and thermal plasticity of abdominal pigmentation in Drosophila melanogaster females. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, P.; Kunderfranco, P.; Greco, C.; Guffanti, A.; Stirparo, G.G.; Rusconi, F.; Rizzi, R.; Di Pasquale, E.; Locatelli, S.L.; Latronico, M.V.; et al. DOT1L-mediated H3K79me2 modification critically regulates gene expression during cardiomyocyte differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Z.; Banday, S.; Pandita, T.K.; Altaf, M. The many faces of histone H3K79 methylation. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2016, 768, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogliotti, Y.S.; Ross, P.J. Mechanisms of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation remodeling during early mammalian development. Epigenetics 2012, 7, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, A.H.; Wang, S.; Ko, K.D.; Zare, H.; Tsai, P.F.; Feng, X.; Vivanco, K.O.; Ascoli, A.M.; Gutierrez-Cruz, G.; Krebs, J.; et al. Roles of H3K27me2 and H3K27me3 Examined during Fate Specification of Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichol, J.N.; Dupere-Richer, D.; Ezponda, T.; Licht, J.D.; Miller, W.H., Jr. H3K27 Methylation: A Focal Point of Epigenetic Deregulation in Cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2016, 131, 59–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Fan, H.; Grimm, S.A.; Kim, J.J.; Li, L.; Guo, Y.; Petell, C.J.; Tan, X.F.; Zhang, Z.M.; Coan, J.P.; et al. DNMT1 reads heterochromatic H4K20me3 to reinforce LINE-1 DNA methylation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvalan, A.Z.; Coller, H.A. Methylation of histone 4’s lysine 20: A critical analysis of the state of the field. Physiol. Genomics 2021, 53, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, S. Degrees make all the difference: The multifunctionality of histone H4 lysine 20 methylation. Epigenetics 2009, 4, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Langlais, D.; Nijnik, A. Histone H2A deubiquitinases in the transcriptional programs of development and hematopoiesis: A consolidated analysis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2023, 157, 106384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regadas, I.; Dahlberg, O.; Vaid, R.; Ho, O.; Belikov, S.; Dixit, G.; Deindl, S.; Wen, J.; Mannervik, M. A unique histone 3 lysine 14 chromatin signature underlies tissue-specific gene regulation. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 1766–1780 e1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, Q.; Xiong, J.; Zhu, B. Histone H3K27 acetylation is dispensable for enhancer activity in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, L.A.; Shi, J.; Rohira, A.D.; Feng, Q.; Zhu, B.; Bedford, M.T.; Sagum, C.A.; Jung, S.Y.; Qin, J.; Tsai, M.J.; et al. Acetylation on histone H3 lysine 9 mediates a switch from transcription initiation to elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 14456–14472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauwel, B.; Jang, S.M.; Cassano, M.; Kapopoulou, A.; Barde, I.; Trono, D. Release of human cytomegalovirus from latency by a KAP1/TRIM28 phosphorylation switch. Elife 2015, 4, e06068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, D.C.; Ayyanathan, K.; Negorev, D.; Maul, G.G.; Rauscher, F.J., 3rd. SETDB1: A novel KAP-1-associated histone H3, lysine 9-specific methyltransferase that contributes to HP1-mediated silencing of euchromatic genes by KRAB zinc-finger proteins. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, G.A.; Pandiloski, N.; Douse, C.H.; Modis, Y. Structure and functional mapping of the KRAB-KAP1 repressor complex. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e111179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, E.; Sinclair, J. Latency-associated upregulation of SERBP1 is important for the recruitment of transcriptional repressors to the viral major immediate early promoter of human cytomegalovirus during latent carriage. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 999290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groner, A.C.; Meylan, S.; Ciuffi, A.; Zangger, N.; Ambrosini, G.; Denervaud, N.; Bucher, P.; Trono, D. KRAB-zinc finger proteins and KAP1 can mediate long-range transcriptional repression through heterochromatin spreading. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, C.G.; Kulesza, C.A. Polycomb repressive complex 2 targets murine cytomegalovirus chromatin for modification and associates with viral replication centers. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Albright, E.R.; Lee, J.H.; Jacobs, D.; Kalejta, R.F. Cellular defense against latent colonization foiled by human cytomegalovirus UL138 protein. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1501164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svrlanska, A.; Reichel, A.; Schilling, E.M.; Scherer, M.; Stamminger, T.; Reuter, N. A Noncanonical Function of Polycomb Repressive Complexes Promotes Human Cytomegalovirus Lytic DNA Replication and Serves as a Novel Cellular Target for Antiviral Intervention. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e02143-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sourvinos, G.; Morou, A.; Sanidas, I.; Codruta, I.; Ezell, S.A.; Doxaki, C.; Kampranis, S.C.; Kottakis, F.; Tsichlis, P.N. The downregulation of GFI1 by the EZH2-NDY1/KDM2B-JARID2 axis and by human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) associated factors allows the activation of the HCMV major IE promoter and the transition to productive infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai-Schmiedel, J.; Karniely, S.; Lau, B.; Ezra, A.; Eliyahu, E.; Nachshon, A.; Kerr, K.; Suarez, N.; Schwartz, M.; Davison, A.J.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus long noncoding RNA4.9 regulates viral DNA replication. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaszynski, L.A.; Wen, D.; Dewell, S.; Whitcomb, S.J.; Lin, M.; Diaz, N.; Elsasser, S.J.; Chapgier, A.; Goldberg, A.D.; Canaani, E.; et al. Hira-dependent histone H3.3 deposition facilitates PRC2 recruitment at developmental loci in ES cells. Cell 2013, 155, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioudinkova, E.; Arcangeletti, M.C.; Rynditch, A.; De Conto, F.; Motta, F.; Covan, S.; Pinardi, F.; Razin, S.V.; Chezzi, C. Control of human cytomegalovirus gene expression by differential histone modifications during lytic and latent infection of a monocytic cell line. Gene 2006, 384, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kew, V.G.; Yuan, J.; Meier, J.; Reeves, M.B. Mitogen and stress activated kinases act co-operatively with CREB during the induction of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene expression from latency. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forte, E.; Li, M.; Ayaloglu Butun, F.; Hu, Q.; Borst, E.M.; Schipma, M.J.; Piunti, A.; Shilatifard, A.; Terhune, S.S.; Abecassis, M.; et al. Critical Role for the Human Cytomegalovirus Major Immediate Early Proteins in Recruitment of RNA Polymerase II and H3K27Ac To an Enhancer-Like Element in Ori Lyt. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0314422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cei, S.A.; Rodriguez Huete, A.; Colletti, K.S.; Pari, G.S. Human cytomegalovirus DNA replication requires transcriptional activation via an IE2- and UL84-responsive bidirectional promoter element within oriLyt. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 11664–11677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrei, G.; De Clercq, E.; Snoeck, R. Drug targets in cytomegalovirus infection. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2009, 9, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marty, F.M.; Ljungman, P.; Chemaly, R.F.; Maertens, J.; Dadwal, S.S.; Duarte, R.F.; Haider, S.; Ullmann, A.J.; Katayama, Y.; Brown, J.; et al. Letermovir Prophylaxis for Cytomegalovirus in Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2433–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biron, K.K. Antiviral drugs for cytomegalovirus diseases. Antivir. Res. 2006, 71, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.; Boivin, G. Human cytomegalovirus resistance to antiviral drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, T.; Sifontis, N. Drug interactions and toxicities associated with the antiviral management of cytomegalovirus infection. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2010, 67, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, M.J.; Hyde, T.B.; Schmid, D.S. Review of cytomegalovirus shedding in bodily fluids and relevance to congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2011, 21, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, J. The Immunology of Posttransplant CMV Infection: Potential Effect of CMV Immunoglobulins on Distinct Components of the Immune Response to CMV. Transplantation 2016, 100 (Suppl. S3), S11–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Arminio Monforte, A.; Lepri, A.C.; Rezza, G.; Pezzotti, P.; Antinori, A.; Phillips, A.N.; Angarano, G.; Colangeli, V.; De Luca, A.; Ippolito, G.; et al. Insights into the reasons for discontinuation of the first highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimen in a cohort of antiretroviral naive patients. AIDS 2000, 14, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, M.J.; Deeks, S.G.; Margolis, D.M.; Siliciano, R.F.; Swanstrom, R. HIV reservoirs: What, where and how to target them. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi, M.B.; Firoz, A.S.; Imam, S.N.; Alzaman, N.; Samman, M.A. Epigenetics of human diseases and scope in future therapeutics. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2017, 12, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosavi, A.; Motevalizadeh Ardekani, A. Role of Epigenetics in Biology and Human Diseases. Iran. Biomed. J. 2016, 20, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, G.; Liang, G.; Aparicio, A.; Jones, P.A. Epigenetics in human disease and prospects for epigenetic therapy. Nature 2004, 429, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hao, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Li, P.; Deng, C.; Di, L.J. Epigenetic targeting drugs potentiate chemotherapeutic effects in solid tumor therapy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, R.; Ni, J.; Zhang, X.; Qi, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Chen, G. Recent Advances in enhancer of zeste homolog 2 Inhibitors: Structural insights and therapeutic applications. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 154, 108070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylla, J.L.S.; Hoffman, M.M.; Plesselova, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Calar, K.; Afeworki, Y.; de la Puente, P.; Gnimpieba, E.Z.; Miskimins, W.K.; Messerli, S.M. Reduction of Metastasis via Epigenetic Modulation in a Murine Model of Metastatic Triple Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC). Cancers 2022, 14, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, M.R.; Wills, M.R.; Sinclair, J.H. HCMV Antivirals and Strategies to Target the Latent Reservoir. Viruses 2021, 13, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylwester, A.W.; Mitchell, B.L.; Edgar, J.B.; Taormina, C.; Pelte, C.; Ruchti, F.; Sleath, P.R.; Grabstein, K.H.; Hosken, N.A.; Kern, F.; et al. Broadly targeted human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells dominate the memory compartments of exposed subjects. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 202, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Anderson, J.L.; Lewin, S.R. Getting the “Kill” into “Shock and Kill”: Strategies to Eliminate Latent HIV. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, M.R.; Poole, E.; Lau, B.; Krishna, B.; Sinclair, J.H. The immunology of human cytomegalovirus latency: Could latent infection be cleared by novel immunotherapeutic strategies? Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 12, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moranguinho, I.; Valente, S.T. Block-And-Lock: New Horizons for a Cure for HIV-1. Viruses 2020, 12, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Zn-dependent enzymes | Class | Name | sub-cellular location | Location in body |

| Class I (Rpd3 like) | HDAC1 | Nucleus | Ubiquitous | |

| HDAC2 | ||||

| HDAC3 | ||||

| HDAC8 | ||||

| Class IIa (Hda1 like) | HDAC4 | Nucleus/Cytoplasm | Tissue specific | |

| HDAC5 | ||||

| HDAC7 | ||||

| HDAC9 | ||||

| Class IIb (Hda1 like) | HDAC6 | Cytoplasm | Tissue specific | |

| HDAC10 | ||||

| Class IV (Rpd3/Hda1 like) | HDAC11 | Nucleus/Cytoplasm | Tissue specific | |

| NAD-dependent enzymes | Class III (Sirtuins; Sir2 like) | SIRT (1-7) | Nucleus/Cytoplasm | Ubiquitous: but their expression and activity can vary between different cell types and tissues, influencing the specific biological processes of each tissue. |

| Histone Code | Function | Cites |

|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Epigenetic modification associated with active gene transcription. It is primarily enriched at transcription start sites (TSSs) and is known to play a role in initiating and regulating gene expression. | [119] |

| H3K4me2 | Histone modification that plays a multifaceted role in gene regulation. It is primarily associated with active gene expression and is often found at promoters and enhancers of actively transcribed genes. However, its function can vary depending on the organism and specific genomic context. In some cases, it can also act as a repressive mark. | [120] |

| H3K4me | Histone modification that plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression. It is associated with active gene promoters and enhancers, and is involved in various cellular processes, including development, differentiation, and synaptic plasticity. | [121] |

| H3K36me3 | Epigenetic modification that plays a crucial role in various cellular processes, primarily by influencing transcription and DNA damage repair. It acts as a marker on actively transcribed genes, affecting processes like transcription fidelity, mRNA splicing, and DNA repair. | [122] |

| H3K36me2 | Histone modification that plays a multifaceted role in gene regulation and DNA repair. It is involved in restricting the spread of H3K27me3, recruiting the Rpd3S histone deacetylase complex, and contributing to double-strand break repair. | [123] |

| H3K36me | H3K36me plays a crucial role in maintaining genome stability. It is involved in various cellular processes, including transcription, DNA damage repair, and gene expression regulation. H3K36me modifications are deposited by specific enzymes and recognized by other proteins, influencing chromatin structure and function. | [124] |

| H3K79me3 | Epigenetic mark involved in various cellular processes. It is associated with active transcription, DNA damage repair, and cell cycle regulation. Specifically, H3K79me3 is enriched at actively transcribing genes and is required for the expression of certain genes. It also plays a role in the DNA damage response and cell cycle checkpoint control. | [125] |

| H3K79me2 | H3K79me2 plays a crucial role in regulating gene expression. It is primarily known for its involvement in transcription elongation, where it is associated with faster transcriptional rates. However, it also has roles in other processes like enhancer activity, DNA damage response, and cell fate determination. | [126] |

| H3K79me | Methylation of H3K79 is involved in the regulation of telomeric silencing, cellular development, cell-cycle checkpoint, DNA repair, and regulation of transcription. | [127]. |

| H3K27me3 | Epigenetic modification that generally leads to gene silencing. It is a key player in maintaining stable gene expression patterns, particularly during development and cell differentiation. This modification is associated with inactive gene promoters and is often found in regions where gene expression needs to be suppressed. | [128]. |

| H3K27me2 | Epigenetic modification that plays a role in gene regulation. It is often found in broad chromatin domains and is thought to help prevent the unscheduled activation of enhancers. While it is associated with transcriptional repression, it can also be found at active regulatory regions, suggesting a more complex role than simple silencing. | [129] |

| H3K27me | This modification is primarily associated with gene silencing and plays a crucial role in development and disease. It exists in three methylation states: monomethylation (H3K27me1), dimethylation (H3K27me2), and trimethylation (H3K27me3), each with potentially distinct functions. | [130] |

| H4K20me3 | Epigenetic modification that plays a role in gene regulation and chromatin structure. It is often associated with heterochromatin formation, which is a tightly packed form of DNA that is generally transcriptionally inactive. H4K20me3 is also involved in other cellular processes, including cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, and senescence. | [131] |

| H4K20me2 | Epigenetic modification involved in DNA repair and DNA replication. | [132] |

| H4K20me | Epigenetic modification that plays a crucial role in various cellular processes, including DNA damage response, chromatin structure, gene expression, and cell cycle regulation. It exists in three forms: mono-, di-, and trimethylation (H4K20me1, H4K20me2, and H4K20me3). Each form has distinct functions and is regulated by different enzymes. | [133] |

| H2AK119ub | Histone modification primarily associated with gene repression. It is deposited on chromatin by the Polycomb Repressive Complex 1 (PRC1) and is involved in regulating various biological processes like development, tissue homeostasis, and potentially disease. | [134] |

| H3K14ac | Chromatin modification that plays a significant role in gene regulation and DNA repair. It is known to be associated with active gene expression and facilitates access to DNA by altering chromatin structure. Specifically, H3K14ac enhances the binding of chromatin remodeling complexes (RSC), which are crucial for DNA repair and transcription initiation. | [135] |

| H3K27ac | Epigenetic modification, primarily known for its role in activating gene expression and marking active enhancers. It is a key indicator of regions where DNA is more accessible and where transcription is likely to be occurring. | [136] |

| H3K9ac | Epigenetic modification that generally promotes gene transcription. It is associated with active promoters and enhancers, and helps to recruit proteins necessary for transcription. | [137] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cevenini, A.; De Antonellis, P.; Mazzarelli, L.L.; Sarno, L.; D’Alessandro, P.; Pellicano, M.; Salomè, S.; Raimondi, F.; Guida, M.; Maruotti, G.M.; et al. Lytic or Latent Phase in Human Cytomegalovirus Infection: An Epigenetic Trigger. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311554

Cevenini A, De Antonellis P, Mazzarelli LL, Sarno L, D’Alessandro P, Pellicano M, Salomè S, Raimondi F, Guida M, Maruotti GM, et al. Lytic or Latent Phase in Human Cytomegalovirus Infection: An Epigenetic Trigger. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311554

Chicago/Turabian StyleCevenini, Armando, Pasqualino De Antonellis, Laura Letizia Mazzarelli, Laura Sarno, Pietro D’Alessandro, Massimiliano Pellicano, Serena Salomè, Francesco Raimondi, Maurizio Guida, Giuseppe Maria Maruotti, and et al. 2025. "Lytic or Latent Phase in Human Cytomegalovirus Infection: An Epigenetic Trigger" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311554

APA StyleCevenini, A., De Antonellis, P., Mazzarelli, L. L., Sarno, L., D’Alessandro, P., Pellicano, M., Salomè, S., Raimondi, F., Guida, M., Maruotti, G. M., & Miceli, M. (2025). Lytic or Latent Phase in Human Cytomegalovirus Infection: An Epigenetic Trigger. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11554. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311554