High-Temperature Synthesis of High-Entropy Alloy PtPd_CoNiCu Nanoparticles as a Catalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

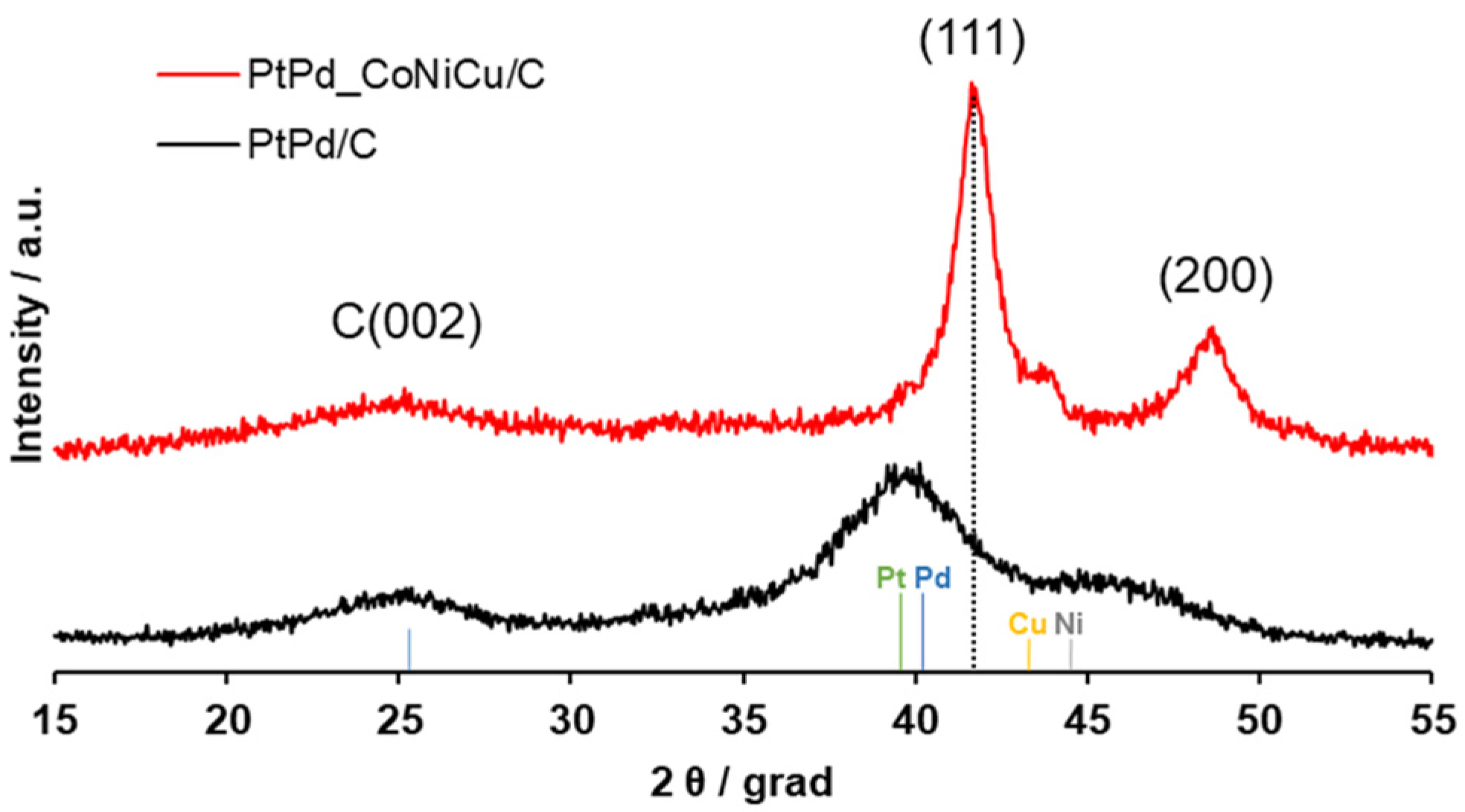

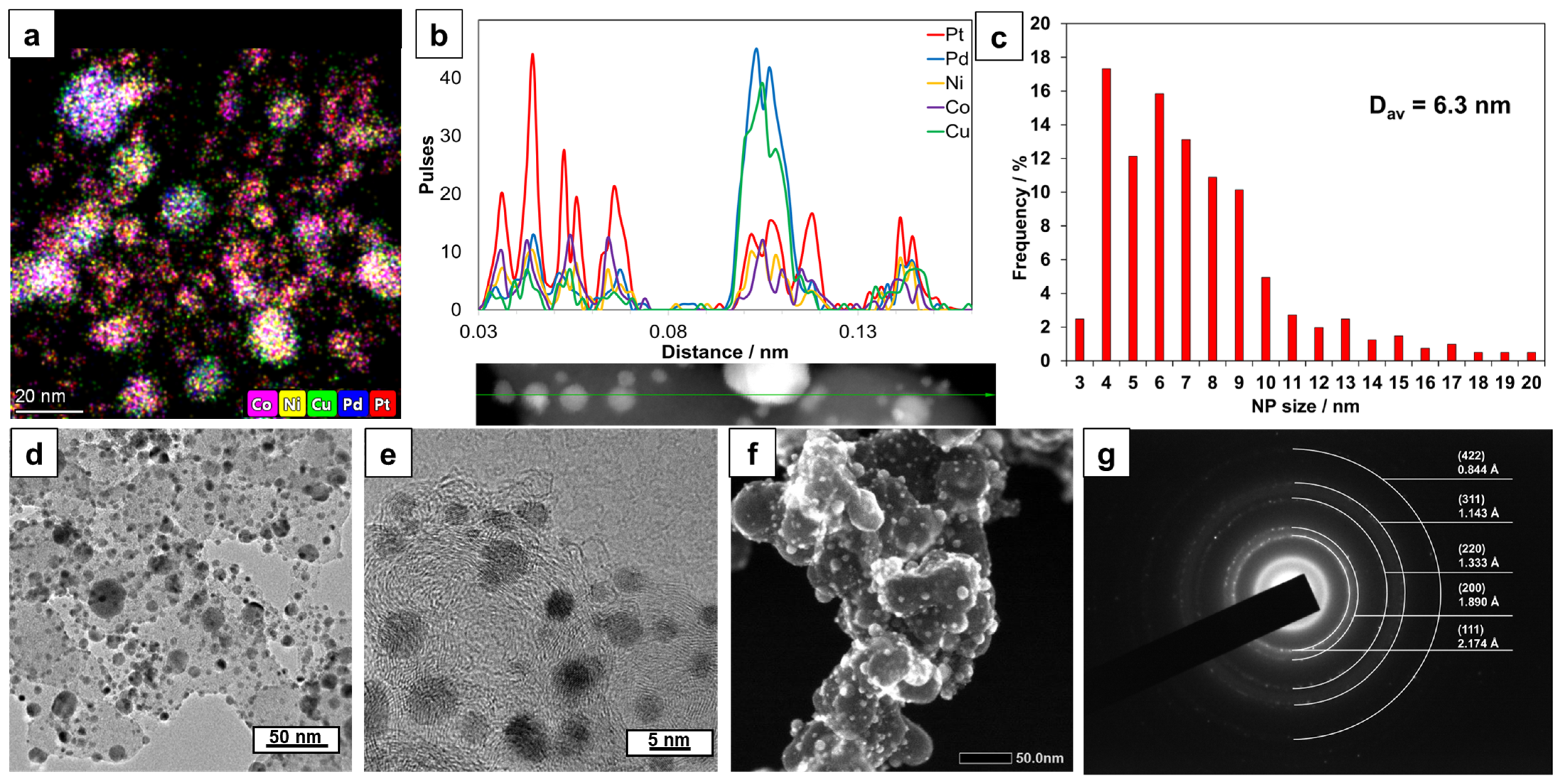

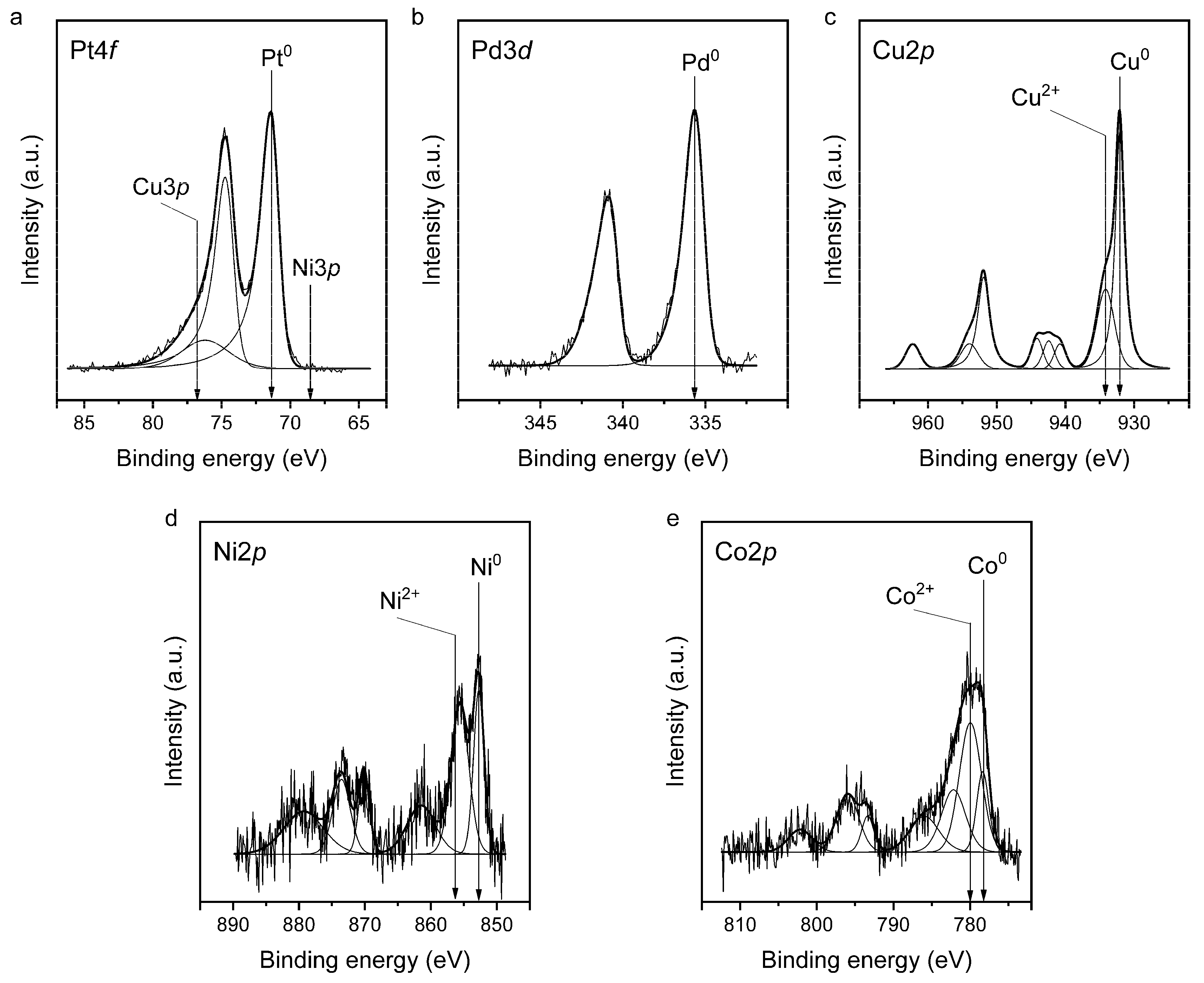

2.1. Composition and Structure of the PtPd_CoNiCu/C Catalyst

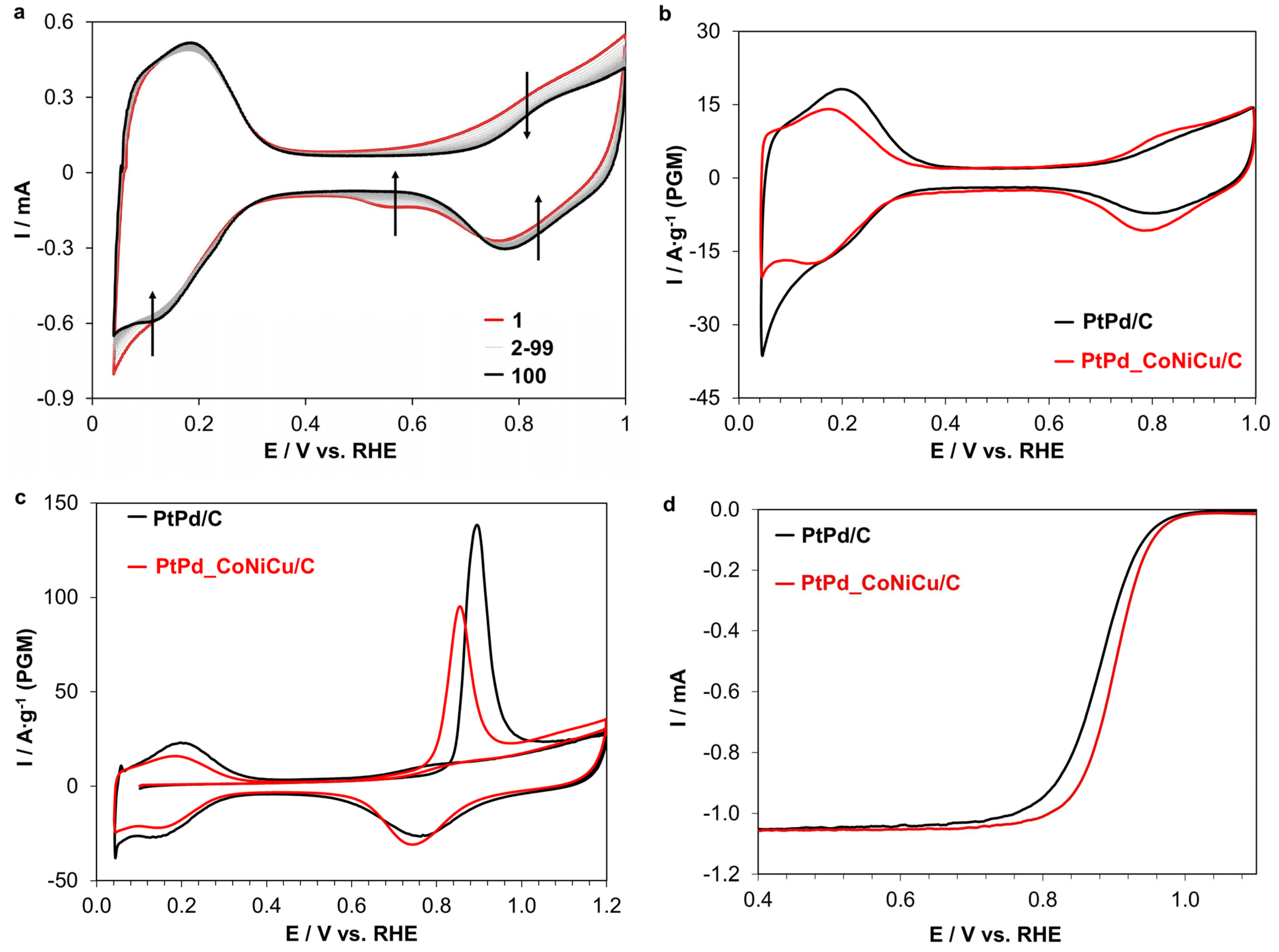

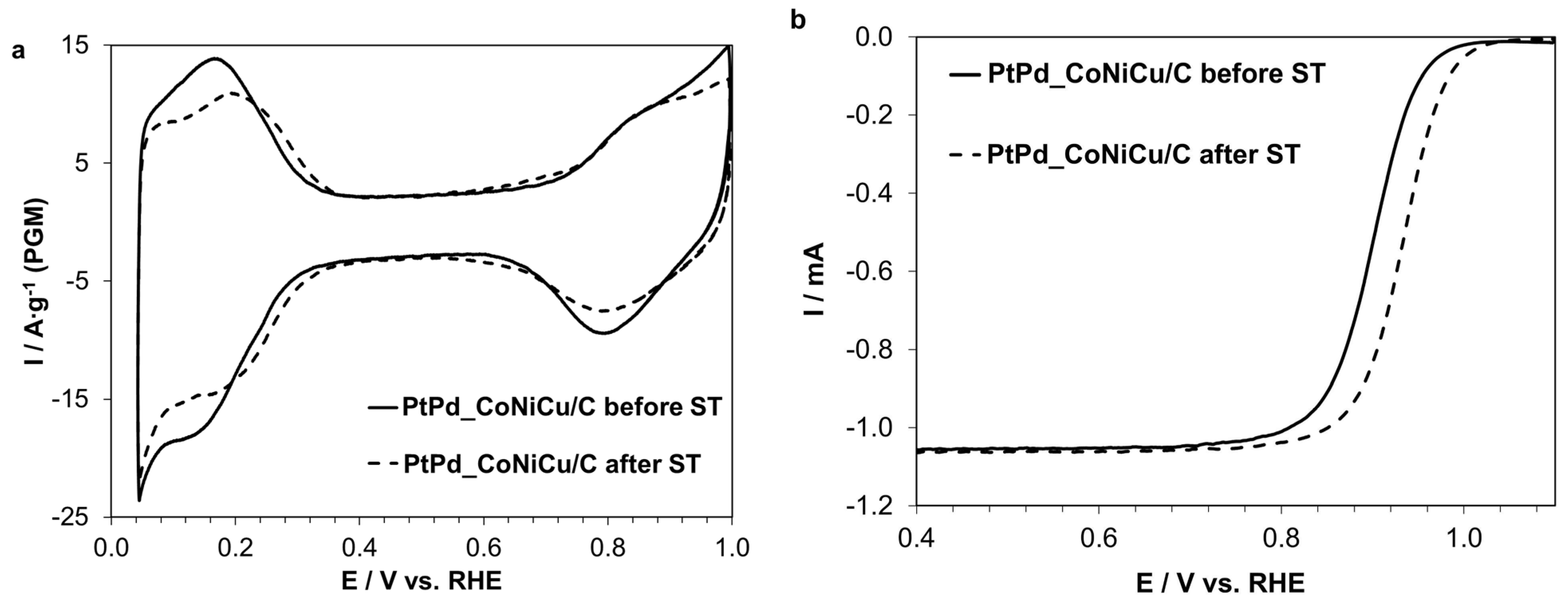

2.2. Electrochemical Characteristics of the PtPd_CoNiCu/C Catalyst

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis

4.1.1. Preparation of PtPd/C Materials

4.1.2. Synthesis of PtPd_CoNiCu/C Catalysts

4.2. Catalyst Characterization Techniques

4.3. Methods for Studying Catalytic Activity

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zaman, S.; Huang, L.; Douka, A.I.; Yang, H.; You, B.; Xia, B.Y. Oxygen Reduction Electrocatalysts toward Practical Fuel Cells: Progress and Perspectives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 17832–17852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, K.; Nagai, T.; Kuwaki, A.; Jinnouchi, R.; Morimoto, Y. Challenges in Applying Highly Active Pt-Based Nanostructured Catalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reactions to Fuel Cell Vehicles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, T.A.M.; Smith, K.; Hack, J.; Rasha, L.; Rana, Z.; Angel, G.M.A.; Shearing, P.R.; Miller, T.S.; Brett, D.J.L. Engineering Catalyst Layers for Next-Generation Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells: A Review of Design, Materials, and Methods. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2101025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallnöfer-Ogris, E.; Poimer, F.; Köll, R.; Macherhammer, M.-G.; Trattner, A. Main Degradation Mechanisms of Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cell Stacks—Mechanisms, Influencing Factors, Consequences, and Mitigation Strategies. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 1159–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Weber, P.; Oezaslan, M. Recent Advances of Various Pt-Based Catalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) in Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs). Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 2023, 40, 101337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priamushko, T.; Kormányos, A.; Cherevko, S. What Do We Know about the Electrochemical Stability of High-Entropy Alloys? Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2024, 44, 101020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, J.S.; Rittiruam, M.; Saelee, T.; Márquez, V.; Shaikh, N.S.; Khajondetchairit, P.; Pathan, S.; Kanjanaboos, P.; Taniike, T.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; et al. First-Principles and Experimental Insight of High-Entropy Materials as Electrocatalysts for Energy-Related Applications: Hydrogen Evolution, Oxygen Evolution, and Oxygen Reduction Reactions. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2024, 160, 100813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, W. Recent Progress in High-Entropy Alloys for Catalysts: Synthesis, Applications, and Prospects. Mater. Today Energy 2021, 20, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xia, F.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Fu, X.; Ma, D.; Lin, B.; Wang, J.; Yue, Q.; Kang, Y. High-Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles as a Promising Electrocatalyst to Enhance Activity and Durability for Oxygen Reduction. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 7868–7876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yao, Z.; Gao, W.; Shang, W.; Deng, T.; Wu, J. Nanoscale Design for High Entropy Alloy Electrocatalysts. Small 2024, 20, 2310006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wu, G.; Zhao, S.; Guo, J.; Yan, M.; Hong, X.; Wang, D. Nanoscale High-Entropy Alloy for Electrocatalysis. Matter 2023, 6, 1717–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, J.; Li, B.; Qi, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Dong, P.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Leung, M.K.H. Recent Research Progress on High-Entropy Alloys as Electrocatalytic Materials. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 918, 165585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Zhang, X.; Xue, Y.; Huang, H.; Jiang, Q.; Tang, J. A Review of Properties and Applications of Utilization of High Entropy Alloys in Oxygen Evolution Reactions. Mol. Catal. 2024, 569, 114571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Nairan, A.; Feng, Z.; Zheng, R.; Bai, Y.; Khan, U.; Gao, J. Unlocking the Potential of High Entropy Alloys in Electrochemical Water Splitting: A Review. Small 2024, 20, 2311929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, T.; Savan, A.; Garzón-Manjón, A.; Meischein, M.; Scheu, C.; Ludwig, A.; Schuhmann, W. Toward a Paradigm Shift in Electrocatalysis Using Complex Solid Solution Nanoparticles. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tang, X.; Jia, H.; Li, H.; Xie, G.; Liu, X.; Lin, X.; Qiu, H.-J. Nanoporous High-Entropy Alloys with Low Pt Loadings for High-Performance Electrochemical Oxygen Reduction. J. Catal. 2020, 383, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Guo, P.; Pan, H.; Wu, R. Emerging High-Entropy Compounds for Electrochemical Energy Storage and Conversion. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 145, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failla, S.; Galizia, P.; Fu, S.; Grasso, S.; Sciti, D. Formation of High Entropy Metal Diborides Using Arc-Melting and Combinatorial Approach to Study Quinary and Quaternary Solid Solutions. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-D.; Regulacio, M.D.; Ye, E.; Han, M.-Y. Chemical Routes to Top-down Nanofabrication. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, N.; Khan, A.M.; Shujait, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Ikram, M.; Imran, M.; Haider, J.; Khan, M.; Khan, Q.; Maqbool, M. Synthesis of Nanomaterials Using Various Top-down and Bottom-up Approaches, Influencing Factors, Advantages, and Disadvantages: A Review. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2022, 300, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.-J.; Fang, G.; Wen, Y.; Liu, P.; Xie, G.; Liu, X.; Sun, S. Nanoporous High-Entropy Alloys for Highly Stable and Efficient Catalysts. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2019, 7, 6499–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.H.; Ma, Y.J.; Cai, Y.P.; Wang, G.J.; Meng, X.K. High Strength Dual-Phase High Entropy Alloys with a Tunable Nanolayer Thickness. Scr. Mater. 2019, 173, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Saray, M.T.; Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Chen, G.; Huang, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhong, G.; Dong, Q.; Hong, M.; et al. Scalable Synthesis of High Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles by Microwave Heating. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 14928–14937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broge, N.L.N.; Bertelsen, A.D.; Søndergaard-Pedersen, F.; Iversen, B.B. Facile Solvothermal Synthesis of Pt–Ir–Pd–Rh–Ru–Cu–Ni–Co High-Entropy Alloy Nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahara, Y.; Ohyama, J.; Sawabe, K.; Satsuma, A. Synthesis of Supported Bimetal Catalysts Using Galvanic Deposition Method. Chem. Rec. 2018, 18, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevelskaya, A.K.; Belenov, S.V.; Gavrilova, A.A.; Lyanguzov, N.V.; Beskopylny, E.R.; Pankov, I.V.; Kokhanov, A.A. High-Temperature Synthesis of PtCo/C Catalysts: The Effect of Pt Loading on Their Structure and Activity. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2026, 323, 118844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, C.W.B.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Lee, K.; Marques, A.L.B.; Marques, E.P.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J. A Review of Heat-Treatment Effects on Activity and Stability of PEM Fuel Cell Catalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. J. Power Sources 2007, 173, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenov, S.; Alekseenko, A.; Pavlets, A.; Nevelskaya, A.; Danilenko, M. Architecture Evolution of Different Nanoparticles Types: Relationship between the Structure and Functional Properties of Catalysts for PEMFC. Catalysts 2022, 12, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, Y.; Xie, X.; Wang, Z.; Yan, C.; Liu, G. Effect of Heat Treatment Temperature on the Pt3Co Binary Metal Catalysts for Oxygen Reduced Reaction and DFT Calculations. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2022, 50, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Cao, C.; Zhao, T.; Huang, Z.; Li, B.; Wieckowski, A.; Ma, J. Synthesis and Application of Core–Shell Co@Pt/C Electrocatalysts for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2013, 223, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zou, L.; Huang, Q.; Zou, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H. Lattice Contracted Ordered Intermetallic Core-Shell PtCo@Pt Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Structure and Origin for Enhanced Oxygen Reduction Reaction. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, H331–H337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhan, X.; Bueno, S.L.A.; Shafei, I.H.; Ashberry, H.M.; Chatterjee, K.; Xu, L.; Tang, Y.; Skrabalak, S.E. Synthesis of Monodisperse High Entropy Alloy Nanocatalysts from Core@shell Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Horiz. 2021, 6, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Q.; Hao, S.; Han, J.; Ding, Y. Dealloyed Nanoporous Materials for Electrochemical Energy Conversion and Storage. EnergyChem 2022, 4, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissmüller, J.; Sieradzki, K. Dealloyed Nanoporous Materials with Interface-Controlled Behavior. MRS Bull. 2018, 43, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Zhu, H. Surface-engineered nanostructured high-entropy alloys for advanced electrocatalysis. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Du, F.; Jin, X. Synthesis of PtCu–based nanocatalysts: Fundamentals and emerging challenges in energy conversion. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 64, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Sun, P.; Luo, C.; Xia, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Sun, L.; Du, F. PtCo-based nanocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction: Recent highlights on synthesis strategy and catalytic mechanism. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 53, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao-Lin, A.; Xie, X.Q.; Wei, D.Y.; Shen, T.; Zheng, Q.N.; Dong, J.C.; Tian, J.H.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.F. High-Loading Platinum-Cobalt Intermetallic Compounds with Enhanced Oxygen Reduction Activity in Membrane Electrode Assemblies. Next Nanotechnol. 2024, 5, 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukrakpam, R.; Luo, J.; He, T.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Njoki, P.; Wanjala, B.N.; Fang, B.; Mott, D.; Yin, J.; et al. Nanoengineered PtCo and PtNi catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction: An assessment of the structural and electrocatalytic properties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 1682–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yin, J.; Feng, B.; Li, F.; Wang, F. One-Pot Synthesis of Unprotected PtPd Nanoclusters with Enhanced Catalytic Activity, Durability, and Methanol-Tolerance for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 473, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, V.; Alekseenko, A.; Belenov, S.; Menshikov, V.; Moguchikh, E.; Novomlinskaya, I.; Paperzh, K.; Pankov, I. Exploring the Potential of Bimetallic PtPd/C Cathode Catalysts to Enhance the Performance of PEM Fuel Cells. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontyev, I.N.; Belenov, S.V.; Guterman, V.E.; Haghi-Ashtiani, P.; Shaganov, A.P.; Dkhil, B. Catalytic Activity of Carbon-Supported Pt Nanoelectrocatalysts. Why Reducing the Size of Pt Nanoparticles Is Not Always Beneficial? J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 5429–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontyev, I.N.; Leontyeva, D.V.; Kuriganova, A.B.; Popov, Y.V.; Maslova, O.A.; Glebova, N.V.; Nechitailov, A.A.; Zelenina, N.K.; Tomasov, A.A.; Hennet, L.; et al. Characterization of the Electrocatalytic Activity of Carbon-Supported Platinum-Based Catalysts by Thermal Gravimetric Analysis. Mendeleev Commun. 2015, 25, 468–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, V.E.; Belenov, S.V.; Krikov, V.V.; Vysochina, L.L.; Yohannes, W.; Tabachkova, N.Y.; Balakshina, E.N. Reasons for the Differences in the Kinetics of Thermal Oxidation of the Support in Pt/C Electrocatalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 23835–23844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenov, S.V.; Men’shchikov, V.S.; Nikulin, A.Y.; Novikovskii, N.M. PtCu/C Materials Doped with Different Amounts of Gold as the Catalysts of Oxygen Electroreduction and Methanol Electrooxidation. Russ. J. Electrochem. 2020, 56, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenov, S.; Pavlets, A.; Paperzh, K.; Mauer, D.; Menshikov, V.; Alekseenko, A.; Pankov, I.; Tolstunov, M.; Guterman, V. The PtM/C (M = Co, Ni, Cu, Ru) Electrocatalysts: Their Synthesis, Structure, Activity in the Oxygen Reduction and Methanol Oxidation Reactions, and Durability. Catalysts 2023, 13, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favilla, P.C.; Acosta, J.J.; Schvezov, C.E.; Sercovich, D.J.; Collet-Lacoste, J.R. Size Control of Carbon-Supported Platinum Nanoparticles Made Using Polyol Method for Low Temperature Fuel Cells. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 101, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, H.; Cao, J.; Wang, Y. Carbon Confinement Engineering of Ultrafine Pt-Based Catalyst for Robust Electrochemical Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Nano Mater. Sci. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zou, J.; Xi, X.; Fan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Banham, D.; Yang, D.; Dong, A. Native Ligand Carbonization Renders Common Platinum Nanoparticles Highly Durable for Electrocatalytic Oxygen Reduction: Annealing Temperature Matters. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2202743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Lee, E.; Nam, J.; Kwon, J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, B.J.; Ham, H.C.; Lee, H. Carbon-Embedded Pt Alloy Cluster Catalysts for Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2400599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, A.; Yan, X.; Xue, W.; Peng, B.; Xin, H.L.; Pan, X.; Duan, X.; Huang, Y. Graphene-Nanopocket-Encaged PtCo Nanocatalysts for Highly Durable Fuel Cell Operation under Demanding Ultralow-Pt-Loading Conditions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Chai, M.; Ming, P.; Zhang, C. Ligand Carbonization In-Situ Derived Ultrathin Carbon Shells Enable High-Temperature Confinement Synthesis of PtCo Alloy Catalysts for High-Efficiency Fuel Cells. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 149060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Peng, B.; Tsai, Y.-H.J.; Zhang, A.; Xu, M.; Zang, W.; Yan, X.; Xing, L.; Pan, X.; Duan, X.; et al. Pt Catalyst Protected by Graphene Nanopockets Enables Lifetimes of over 200,000 h for Heavy-Duty Fuel Cell Applications. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2025, 20, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Hao, X.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Wang, G.; Jiang, K.; Zheng, S. High-Pressure Nitrogen Assisted Synthesis of Small-Sized, Carbon-Encapsulated PtCo Alloy Nanoparticles as Highly Stable Oxygen Reduction Catalysts. Mater. Lett. 2024, 373, 137120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.V.; Kaichev, V.V.; Prosvirin, I.P.; Bukhtiyarov, V.I. Mechanistic Study of Methanol Decomposition and Oxidation on Pt(111). J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 8189–8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal’zhinimaev, B.S.; Kovalyov, E.V.; Kaichev, V.V.; Suknev, A.P.; Zaikovskii, V.I. Catalytic Abatement of VOC Over Novel Pt Fiberglass Catalysts. Top. Catal. 2017, 60, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.S.; Zemlyanov, D.; Storey, J.M.; Ribeiro, F.H. Turnover Rate and Reaction Orders for the Complete Oxidation of Methane on a Palladium Foil in Excess Dioxygen. J. Catal. 2001, 199, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Gossmann, A.F.; Winograd, N. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopic Studies of Palladium Oxides and the Palladium-Oxygen Electrode. Anal. Chem. 1974, 46, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaichev, V.V.; Saraev, A.A.; Matveev, A.V.; Dubinin, Y.V.; Knop-Gericke, A.; Bukhtiyarov, V.I. In Situ NAP-XPS and Mass Spectrometry Study of the Oxidation of Propylene over Palladium. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 4315–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaichev, V.V.; Teschner, D.; Saraev, A.A.; Kosolobov, S.S.; Gladky, A.Y.; Prosvirin, I.P.; Rudina, N.A.; Ayupov, A.B.; Blume, R.; Hävecker, M.; et al. Evolution of Self-Sustained Kinetic Oscillations in the Catalytic Oxidation of Propane over a Nickel Foil. J. Catal. 2016, 334, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.S.; Mannu, P.; Prabhakaran, S.; Nga, T.T.T.; Kim, Y.; Chen, J.-L.; Dong, C.-L.; Yoo, D.J. Trimetallic Oxide Electrocatalyst for Enhanced Redox Activity in Zinc–Air Batteries Evaluated by In Situ Analysis. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2303525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khassin, A.A.; Yurieva, T.M.; Kaichev, V.V.; Bukhtiyarov, V.I.; Budneva, A.A.; Paukshtis, E.A.; Parmon, V.N. Metal–Support Interactions in Cobalt-Aluminum Co-Precipitated Catalysts: XPS and CO Adsorption Studies. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2001, 175, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C.; Payne, B.P.; Grosvenor, A.P.; Lau, L.W.M.; Gerson, A.R.; Smart, R.S.C. Resolving Surface Chemical States in XPS Analysis of First Row Transition Metals, Oxides and Hydroxides: Cr, Mn, Fe, Co and Ni. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 2717–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oezaslan, M.; Hasché, F.; Strasser, P. PtCu3, PtCu and Pt3Cu Alloy Nanoparticle Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction in Alkaline and Acidic Media. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012, 159, B444–B454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menshchikov, V.; Alekseenko, A.; Guterman, V.; Nechitailov, A.; Glebova, N.; Tomasov, A.; Spiridonova, O.; Belenov, S.; Zelenina, N.; Safronenko, O. Effective Platinum-Copper Catalysts for Methanol Oxidation and Oxygen Reduction in Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colmenares, L.; Guerrini, E.; Jusys, Z.; Nagabhushana, K.S.; Dinjus, E.; Behrens, S.; Habicht, W.; Bönnemann, H.; Behm, R.J. Activity, Selectivity, and Methanol Tolerance of Novel Carbon-Supported Pt and Pt3Me (Me = Ni, Co) Cathode Catalysts. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2007, 37, 1413–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Wu, A.; Luo, L.; Wang, C.; Yang, F.; Wei, G.; Xia, G.; Yin, J.; Zhang, J. The Asymmetric Effects of Cu 2+ Contamination in a Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC). Fuel Cells 2020, 20, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlets, A.; Titskaya, E.; Alekseenko, A.; Pankov, I.; Ivanchenko, A.; Falina, I. Operation Features of PEMFCs with De-Alloyed PtCu/C Catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseenko, A.A.; Pavlets, A.S.; Mikheykin, A.S.; Belenov, S.V.; Guterman, E.V. The Integrated Approach to Studying the Microstructure of De-Alloyed PtCu/C Electrocatalysts for PEMFCs. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 631, 157539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chu, W.; Kuang, L.; Bu, Y.; Liu, J.; Jia, G.; Xue, Z.; Qin, H. Carbon-Supported High-Entropy Alloys as Highly Stable Nanocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 178194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, V.; Alekseenko, A.; Belenov, S.; Menshikov, V.; Nevelskaya, A.; Pavlets, A.; Paperzh, K.; Pankov, I. Platinum-Palladium Catalysts of Various Composition in the Oxygen Electroreduction Reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 150, 150166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesinger, M.C. Accessing the Robustness of Adventitious Carbon for Charge Referencing (Correction) Purposes in XPS Analysis: Insights from a Multi-User Facility Data Review. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, U.A.; Schmidt, T.J.; Gasteiger, H.A.; Behm, R.J. Oxygen Reduction on a High-Surface Area Pt/Vulcan Carbon Ca-ta-lyst: A Thin-Film Rotating Ring-Disk Electrode Study. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2001, 495, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenov, S.; Nevelskaya, A.; Nikulin, A.; Tolstunov, M. The Effect of Pretreatment on a PtCu/C Catalyst’s Structure and Functional Characteristics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | ω (M), % | ω (PMG), % | Composition by TXRF | a, Å | Dav Cryst., nm | Dav NP, nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PtPd/C | 28.8 | 28.8 | PtPd0.9 | 3.941 | 1.9 | - |

| PtPd_CoNiCu/C | 36.3 | 19.9 | Pt16Pd17Co24Ni22Cu21 | 3.752 | 5.5 | 6.3 |

| Hispec 3000 | 20 | 20 | Pt | 3.923 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| Sample | ECSA Hads/des, m2/g (PGM) | ECSA CO, m2/g (PGM) | Imass, A/g (PGM) | Ispec, A/m2 (PGM) | E1/2, V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PtPd/C | 83 | 86 | 146 | 1.8 | 0.89 |

| PtPd_CoNiCu/C | 63 | 63 | 269 | 4.3 | 0.90 |

| Hispec 3000 | 84 | - | 254 | 3.0 | 0.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nevelskaya, A.; Gavrilova, A.; Lyanguzov, N.; Tolstunov, M.; Pankov, I.; Kremneva, A.; Gerasimov, E.; Kokhanov, A.; Belenov, S. High-Temperature Synthesis of High-Entropy Alloy PtPd_CoNiCu Nanoparticles as a Catalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311504

Nevelskaya A, Gavrilova A, Lyanguzov N, Tolstunov M, Pankov I, Kremneva A, Gerasimov E, Kokhanov A, Belenov S. High-Temperature Synthesis of High-Entropy Alloy PtPd_CoNiCu Nanoparticles as a Catalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311504

Chicago/Turabian StyleNevelskaya, Alina, Anna Gavrilova, Nikolay Lyanguzov, Mikhail Tolstunov, Ilya Pankov, Anna Kremneva, Evgeny Gerasimov, Andrey Kokhanov, and Sergey Belenov. 2025. "High-Temperature Synthesis of High-Entropy Alloy PtPd_CoNiCu Nanoparticles as a Catalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311504

APA StyleNevelskaya, A., Gavrilova, A., Lyanguzov, N., Tolstunov, M., Pankov, I., Kremneva, A., Gerasimov, E., Kokhanov, A., & Belenov, S. (2025). High-Temperature Synthesis of High-Entropy Alloy PtPd_CoNiCu Nanoparticles as a Catalyst for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11504. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311504