Can the Quality of Semen Affect the Fertilisation Indices of Turkey Eggs?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Parameters of Sperm Functionality

2.2. Antioxidant Status of Turkey Semen

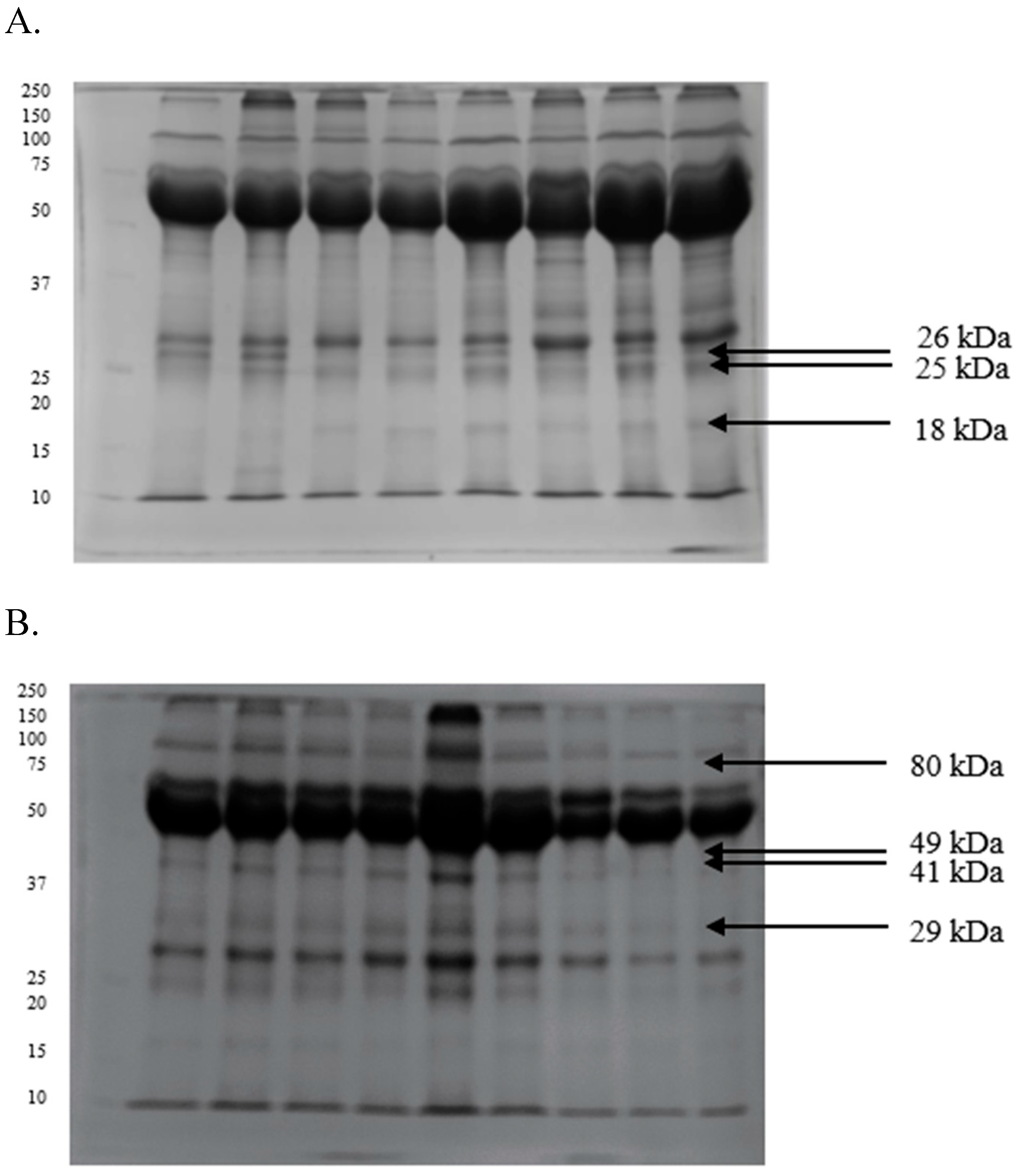

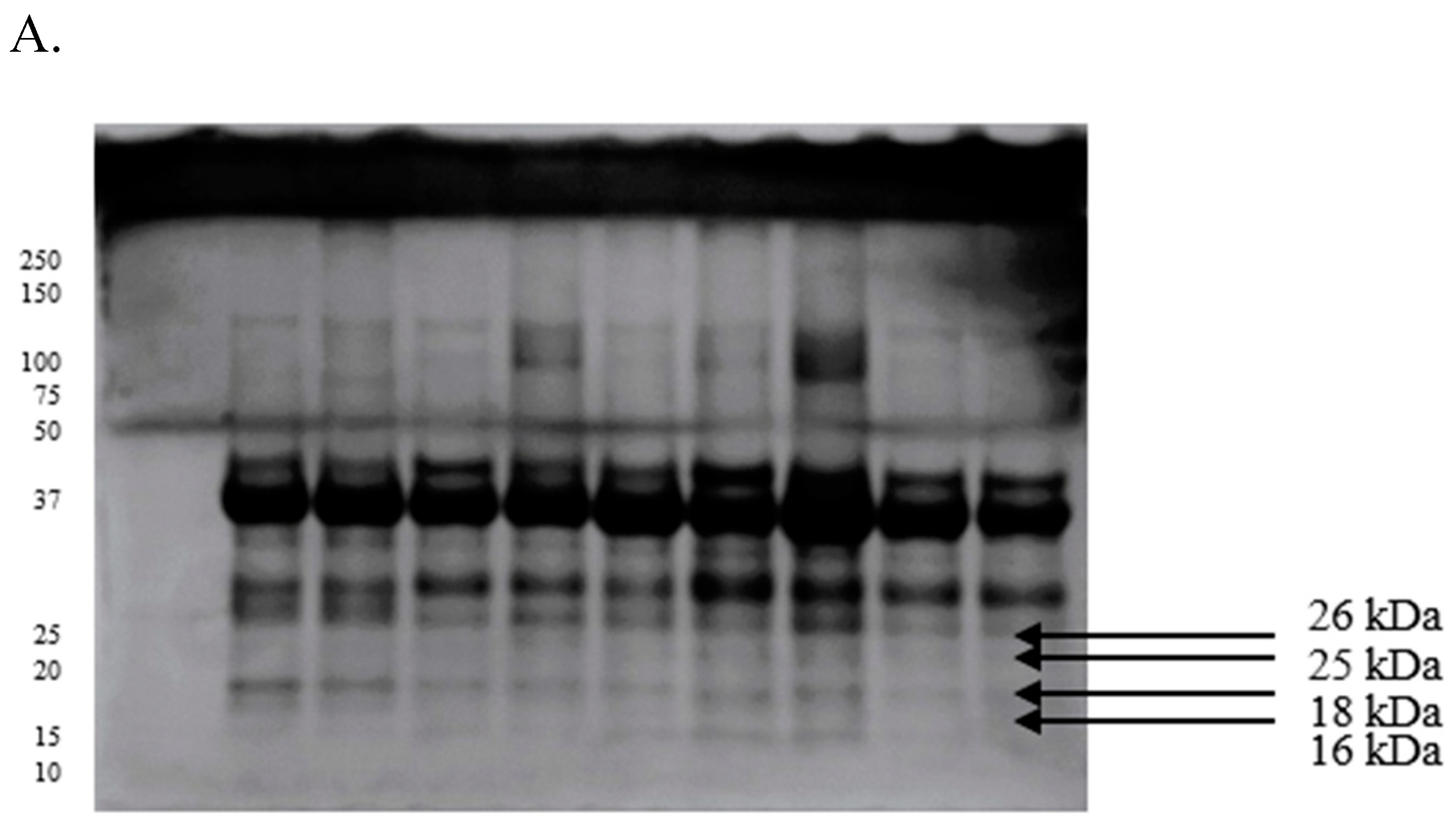

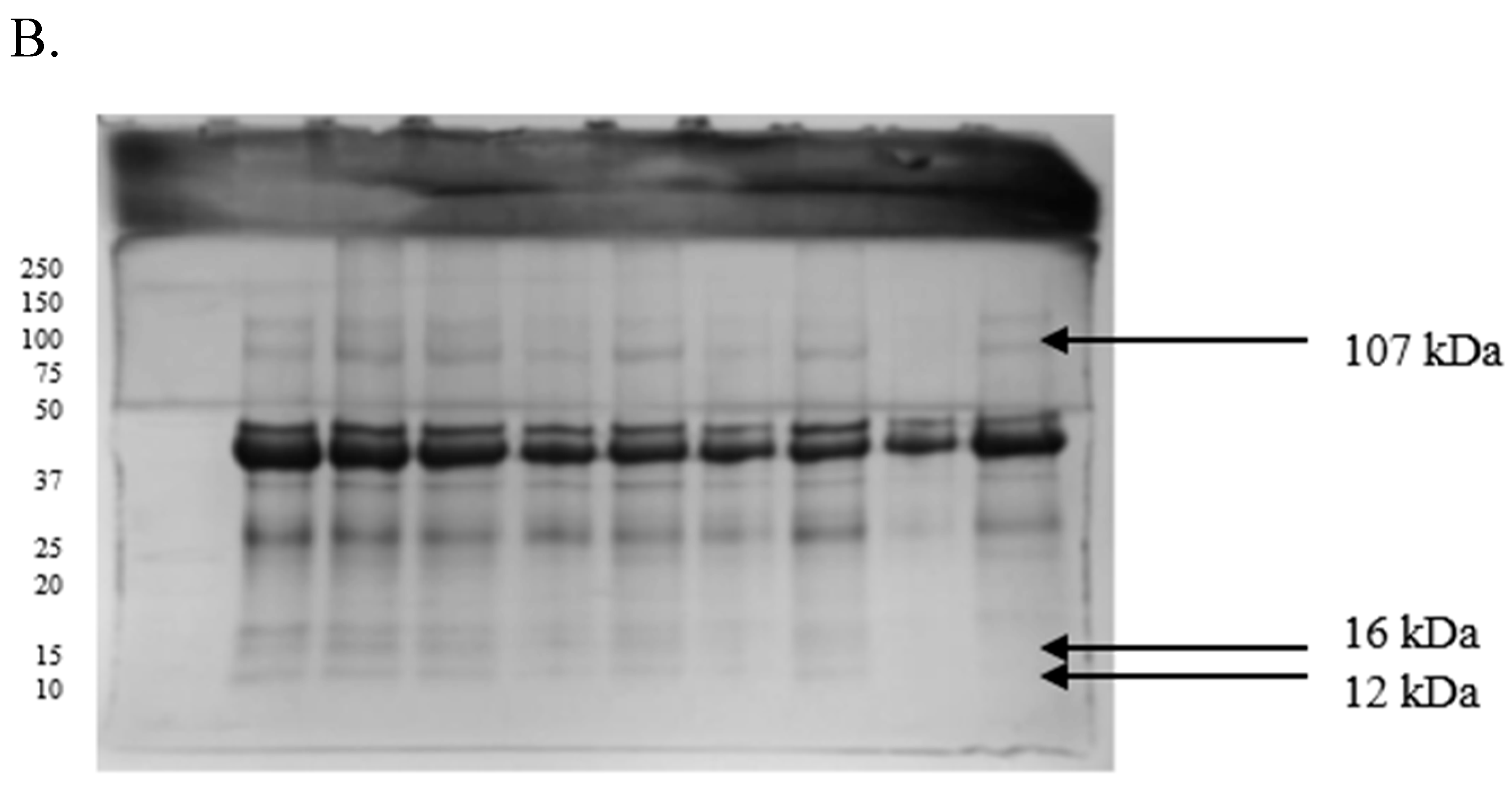

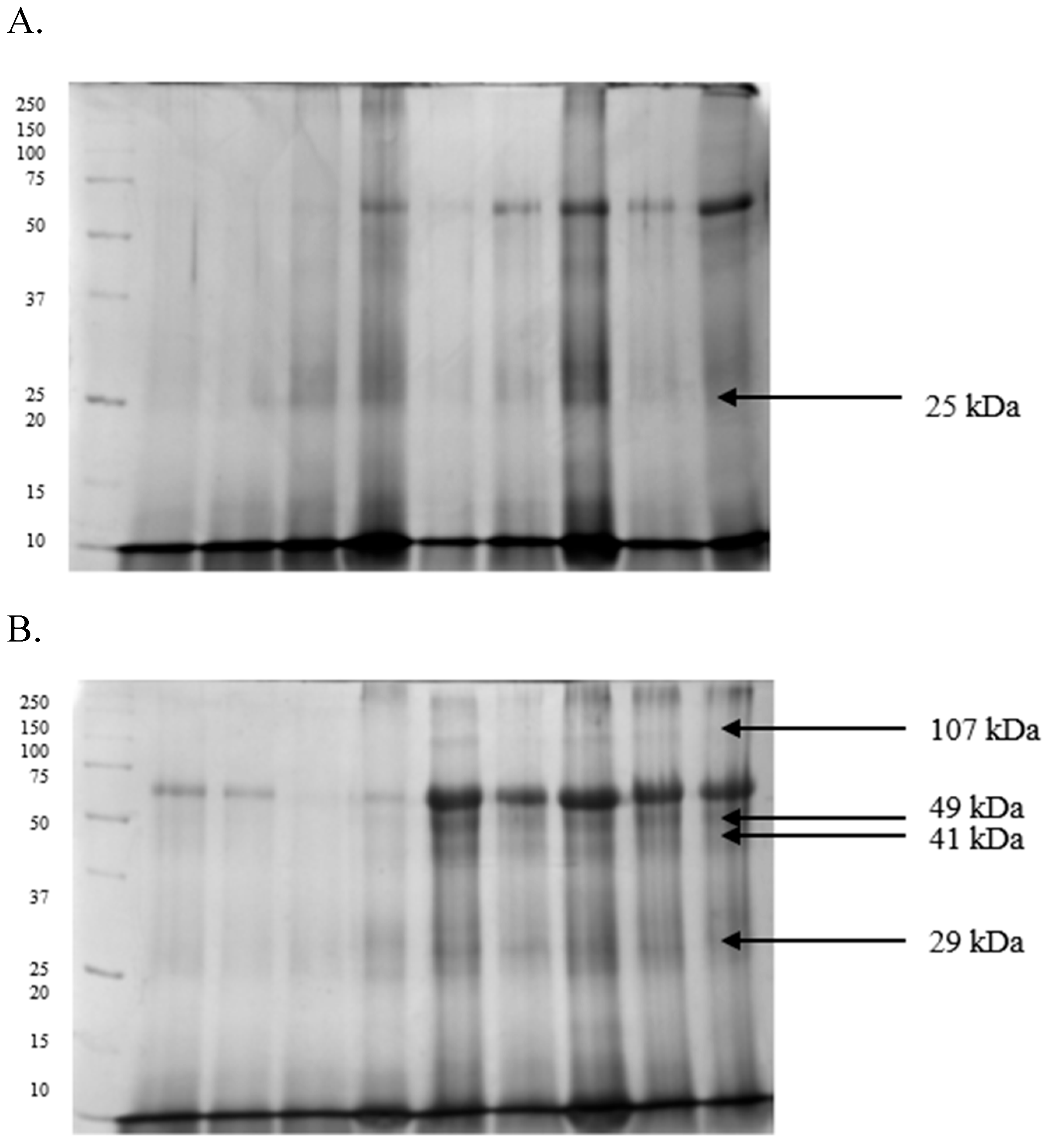

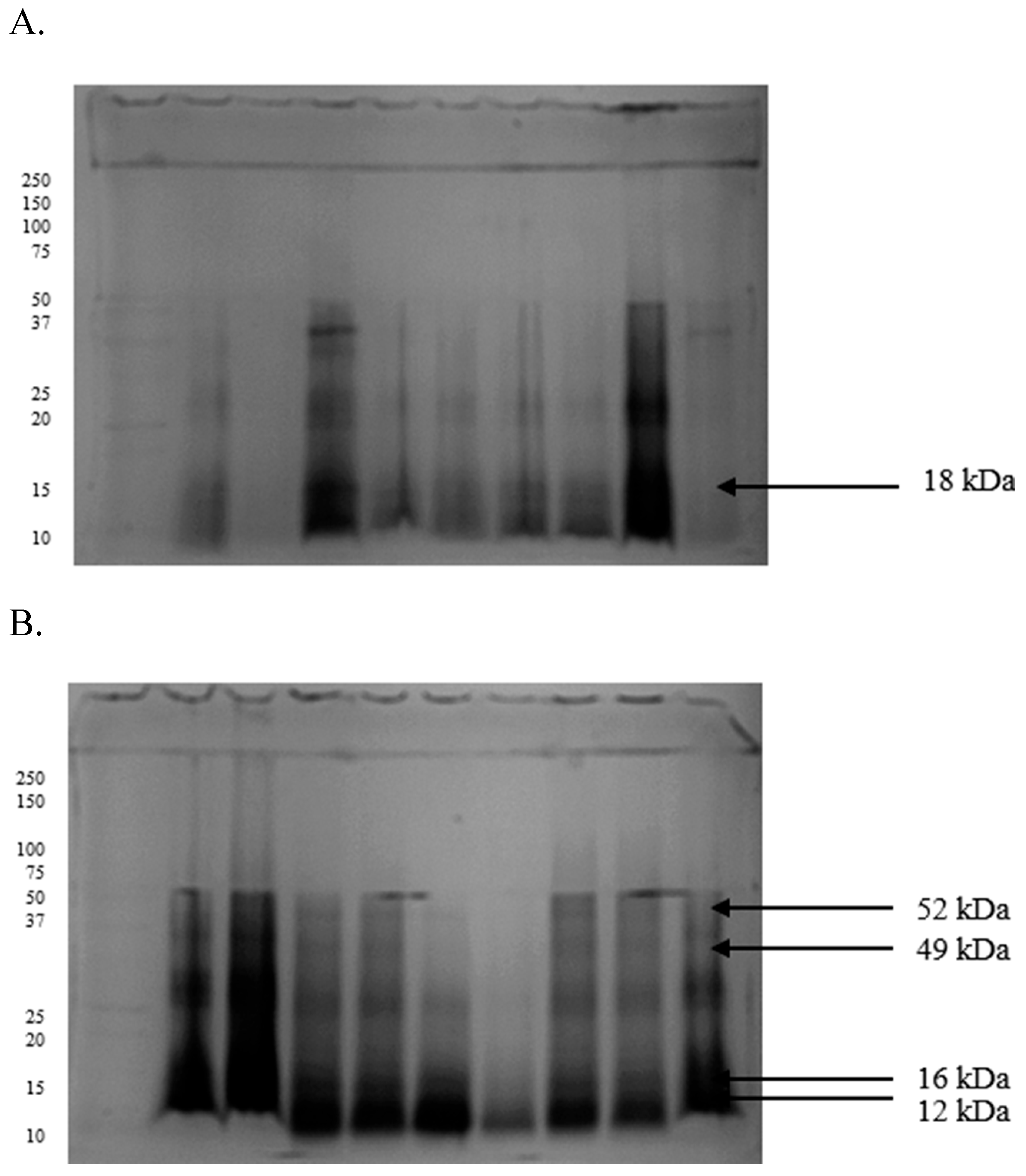

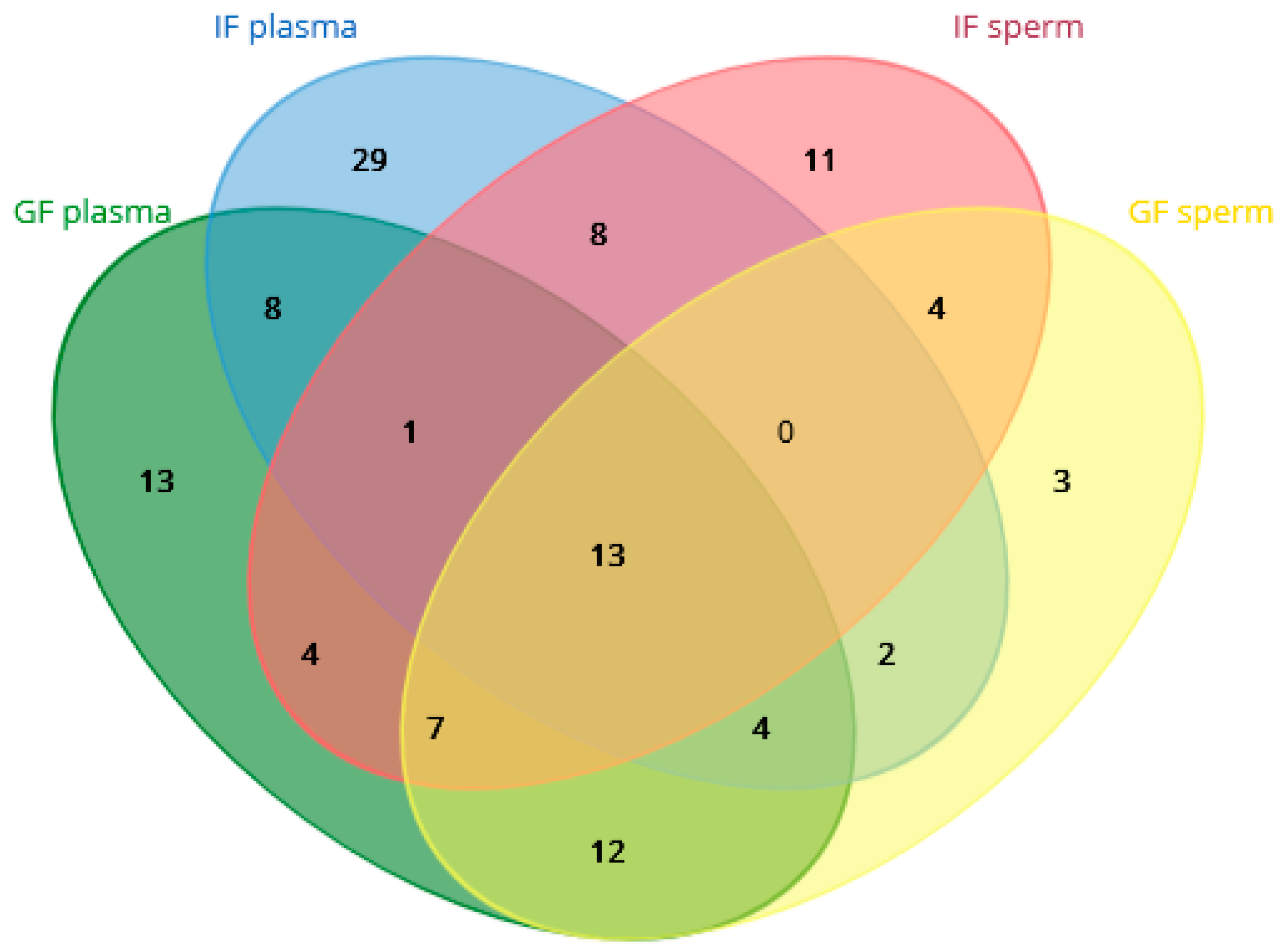

2.3. Differences in the Proteomic Profiles of Seminal Plasma and Spermatozoa from Ejaculates with Good Fertility and Impaired Fertility

2.4. Protein Identification Results

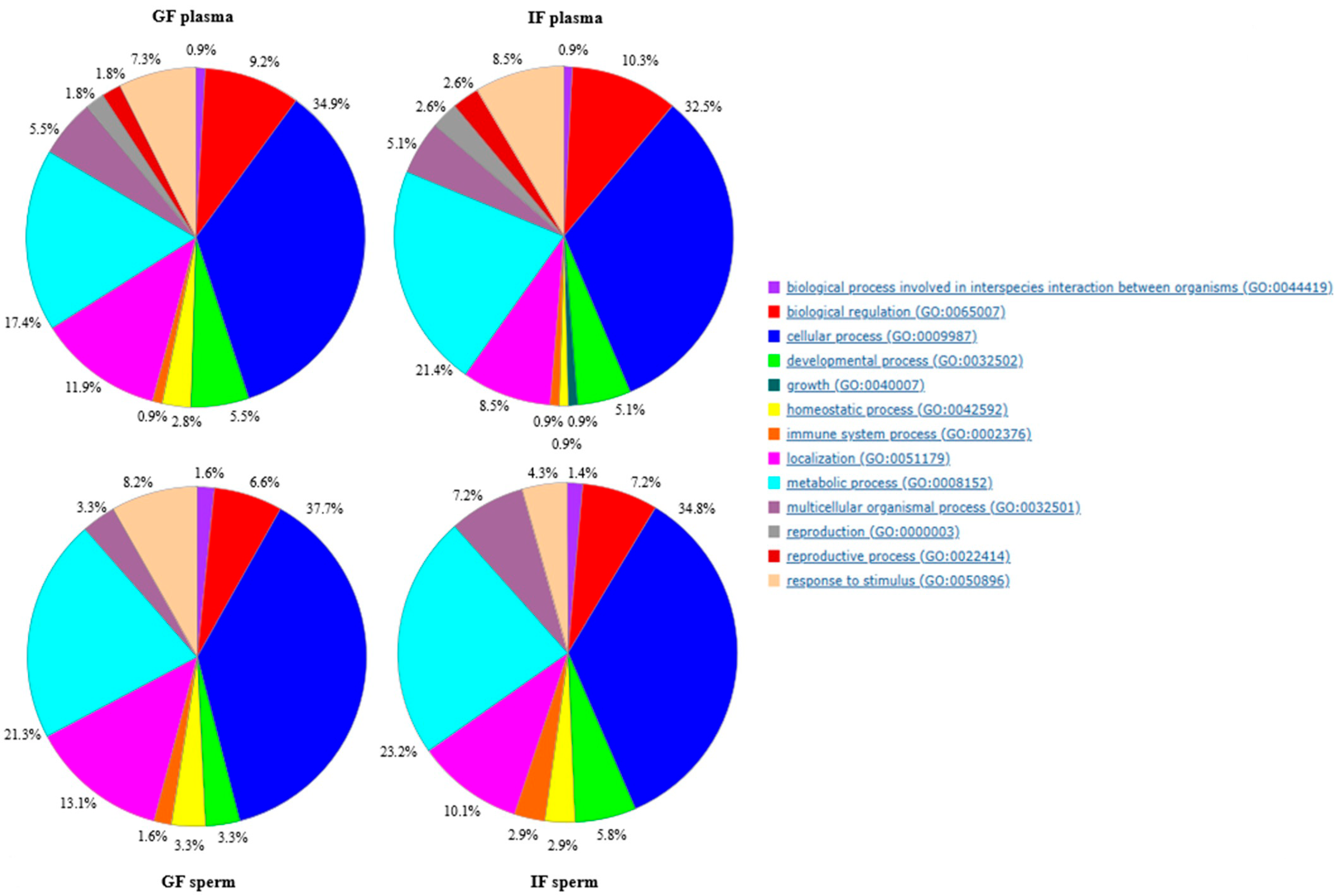

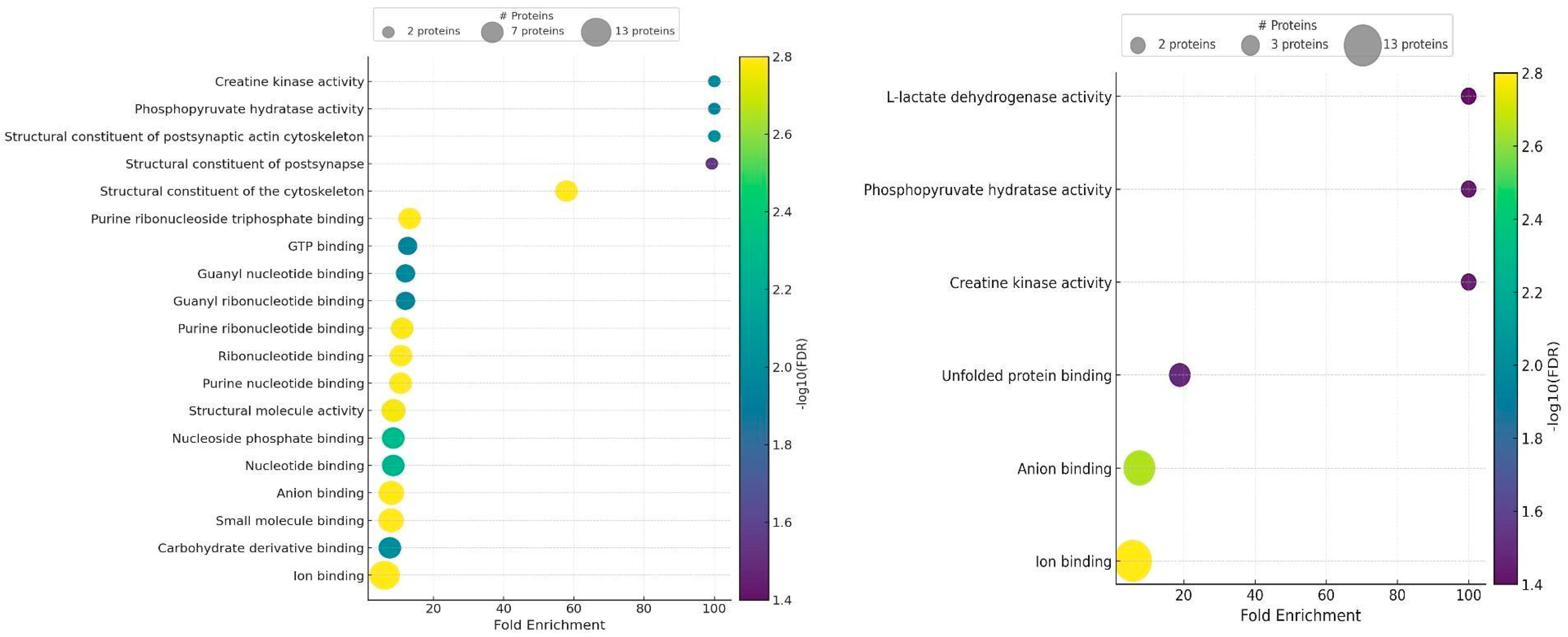

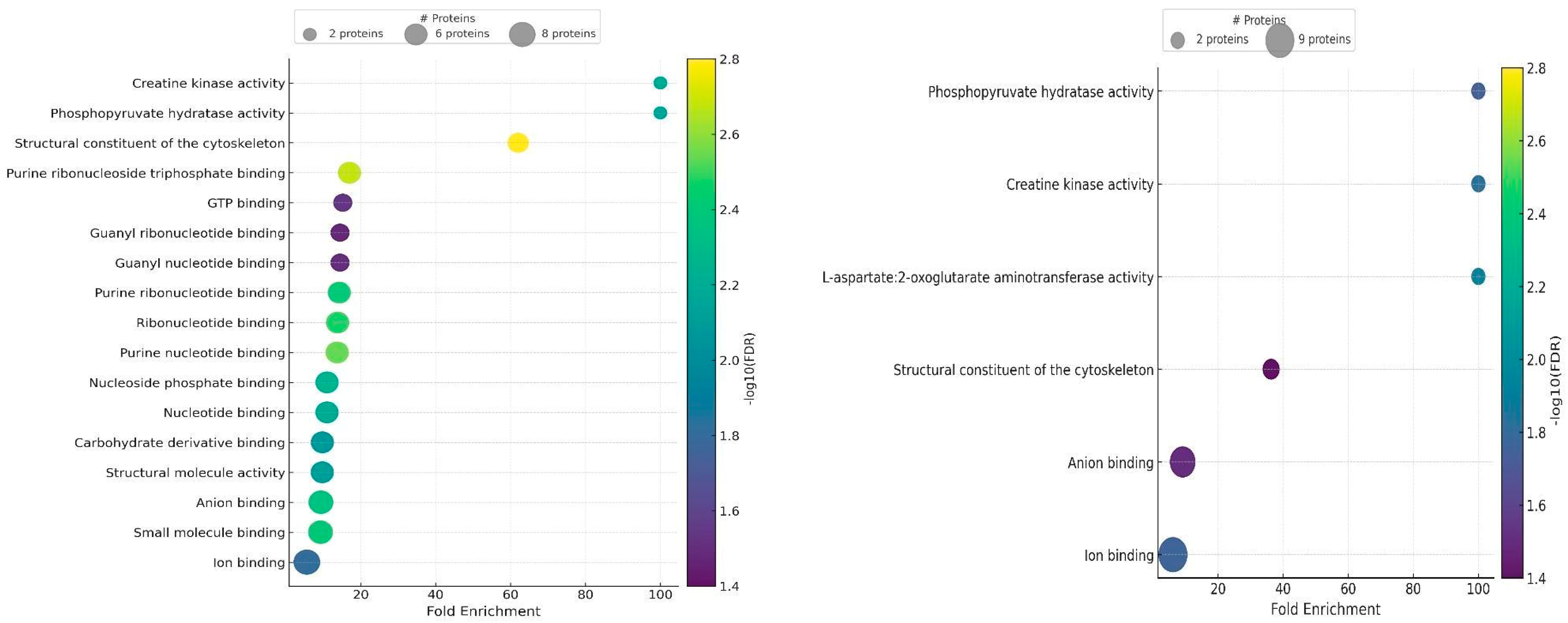

2.5. Gene Ontology Results

3. Discussion

3.1. Potential Impact of Oxidative Stress on IF Semen

3.2. Potential Impact of Proteome Composition on IF Semen

3.3. Potential Impact of Other Factors on IF Semen

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Material Collection

4.2. Assessment of Sperm Concentration

4.3. Assessment of Sperm Motility

4.4. Assessment of Sperm Plasma Membrane Integrity (SYBR-14/PI)

4.5. Assessment of Sperm Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (JC-1/PI)

4.6. Assessment of Nitric Oxide (NO)-Generating Spermatozoa (DAF-2DA)

4.7. Assessment of Antioxidant System Efficiency

4.7.1. Antioxidant Enzyme Triad

Determination of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity

Determination of Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) Activity

Determination of Catalase (CAT) Activity

4.7.2. Antioxidant Agents

Determination of Glutathione (GSH) Content

Determination of Zinc (Zn2+) Content

4.8. Assessment of Oxidative Damage Expressed as Malondialdehyde (MDA) Content

4.9. Analysis of Turkey Semen Protein Profiles by Two Separation Methods

4.9.1. SDS-PAGE Electrophoresis

4.9.2. TRICINE-PAGE Electrophoresis

4.10. Identification of Selected Proteins by Nano LC-MS/MS Mass Spectrometry

4.11. Functional Analysis of Identified Proteins

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ori, A.K. Review of the Factors That Influence Egg Fertility and Hatchability in Poultry. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2011, 10, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotłowska, M.; Kowalski, R.; Glogowski, J.; Jankowski, J.; Ciereszko, A. Gelatinases and serine proteinase inhibitors of seminal plasma and the reproductive tract of turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). Theriogenology 2005, 63, 1667–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, R.J.; Korn, N. Semen quality in the domestic turkey: The yellow semen syndrome. Avian Poult. Biol. Rev. 1997, 8, 109–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, R.A.; Thurston, J. Protein, Cholesterol, Acid Phosphatase and Aspartate Aminotransaminase in the Seminal Plasma of Turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) Producing Normal White or Abnormal Yellow Semen. Biol. Reprod. 1984, 31, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słowińska, M.; Jankowski, J.; Dietrich, G.J.; Karol, H.; Liszewska, E.; Glogowski, J.; Kozłowski, K.; Sartowska, K.; Ciereszko, A. Effect of organic and inorganic forms of selenium in diets on turkey semen quality. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E.F.; Schmehl, M.K.L.; Maki-Laurila, M. Some physical and chemical methods of evaluating semen. In Proceedings of the 3rd Technical Conference on Artificial Insemination and Reproduction, Chicago, IL, USA, 19–21 February 1970; pp. 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, D.J.; Lake, P.E. A comparison of phosphomonoesterase activities in the seminal plasmas of the domestic cock, turkey tom, boar, bull, buck rabbit and of man. Reproduction 1962, 3, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, P.E. Histochemical demonstration of phosphomonoesterase secretion in the genital tract of the domestic cock. Reproduction 1962, 3, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słowińska, M.; Kozłowski, K.; Jankowski, J.; Ciereszko, A. Proteomic analysis of white and yellow seminal plasma in turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo). J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 2785–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafalska, K.T.; Orzołek, A.; Ner-Kluza, J.; Wysocki, P. A Comparison of White and Yellow Seminal Plasma Phosphoproteomes Obtained from Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) Semen. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafalska, K.T.; Orzołek, A.; Ner-Kluza, J.; Wysocki, P. Does the Type of Semen Affect the Phosphoproteome of Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) Spermatozoa? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardyak, L.; Liszewska, E.; Judycka, S.; Machcińska-Zielińska, S.; Karol, H.; Dietrich, M.A.; Gojło, E.; Arent, Z.; Bilińska, B.; Rusco, G.; et al. Liquid semen storage-induced alteration in the protein composition of turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) spermatozoa. Theriogenology 2024, 216, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakst, M.R.; Welch, G.R.; Camp, M.J. Observations of turkey eggs stored up to 27 days and incubated for 8 days: Embryo developmental stage and weight differences and the differentiation of fertilized from unfertilized germinal discs. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 1165–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.G.; Storey, B.T. Differential incorporation of fatty acids into and peroxidative loss of fatty acids from phospholipids of human spermatozoa. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 1995, 42, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Virk, G.; Ong, C.; du Plessis, S.S. Effect of oxidative stress on male reproduction. World J. Mens Health 2014, 32, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partyka, A.; Lukaszewicz, E.; Niżański, W. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes activity in avian semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2012, 134, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Sharma, R.K.; Gupta, S.; Boitrelle, F.; Finelli, R.; Parekh, N.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Saleh, R.; Arafa, M.; Cho, C.L.; et al. Sperm Vitality and Necrozoospermia: Diagnosis, Management, and Results of a Global Survey of Clinical Practice. World J. Mens Health 2022, 40, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanga, B.M.; Qamar, A.Y.; Raza, S.; Bang, S.; Fang, X.; Yoon, K.; Cho, J. Semen evaluation: Methodological advancements in sperm quality-specific fertility assessment—A review. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 34, 1253–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoradová, A.; Kuželová, L.; Vašíek, J.; Baláži, A.; Olexiková, L.; Makarevich, A.; Chrenek, P. Rooster spermatozoa cryopreservation and quality assessment. Cryoletters 2021, 42, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.S.; Kim, U.H.; Lee, M.S.; Lee, S.D.; Cho, S.R. Spermatozoa motility, viability, acrosome integrity, mitochondrial membrane potential and plasma membrane integrity in 0.25 mL and 0.5 mL straw after frozen-thawing in Hanwoo bull. J. Anim. Reprod. Biotechnol. 2020, 35, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalah, T.; Brillard, J.P. Comparison of assessment of fowl sperm viability by eosin-nigrosin and dual fluorescence (SYBR-14/PI). Theriogenology 1998, 50, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xue, F.; Li, Y.; Fu, L.; Bai, H.; Ma, H.; Xu, S.; Chen, J. Differences in semen quality, testicular histomorphology, fertility, reproductive hormone levels, and expression of candidate genes according to sperm motility in Beijing-You chickens. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 4182–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frączek, M.; Kurpisz, M. The redox system in human semen and peroxidative damage of spermatozoa. Postep. Hig. Med. Dosw. 2005, 59, 523–534. [Google Scholar]

- Surai, P.F. Antioxidant Systems in Poultry Biology: Superoxide Dismutase. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.R. Critical Role of Zinc as Either an Antioxidant or a Prooxidant in Cellular Systems. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 20, 9156285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisol, L.; Matorras, R.; Aspichueta, F.; Expósito, A.; Hernández, M.L.; Ruiz-Larrea, M.B.; Mendoza, R.; Ruiz-Sanz, J.I. Glutathione peroxidase activity in seminal plasma and its relationship to classical sperm parameters and in vitro fertilization-intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome. Fertil. Steril. 2012, 97, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujianto, D.A.; Oktarina, M.; Sharma Sharaswati, I.A.; Yulhasri. Hydrogen Peroxide Has Adverse Effects on Human Sperm Quality Parameters, Induces Apoptosis, and Reduces Survival. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 14, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzołek, A.; Rafalska, K.T.; Dziekońska, A.; Rafalska, A.; Zawadzka, M. How Do Taurine and Ergothioneine Additives Improve the Parameters of High- And Low-Quality Turkey Semen During Liquid Preservation? Ann. Anim. Sci. 2025, 25, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atig, F.; Raffa, M.; Habib, B.A.; Kerkeni, A.; Saad, A.; Ajina, M. Impact of seminal trace element and glutathione levels on semen quality of Tunisian infertile men. BMC Urol. 2012, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, E.; Nikzad, H.; Karimian, M. Oxidative stress and male infertility: Current knowledge of pathophysiology and role of antioxidant therapy in disease management. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucak, M.N.; Sarıözkan, S.; Tuncer, P.B.; Sakin, F.; Ateşşahin, A.; Kulaksız, R.; Çevik, M. The effect of antioxidants on post-thawed Angora goat (Capra hircus ancryrensis) sperm parameters, lipid peroxidation and antioxidant activities. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 89, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante-Filho, I.C.; Pasini, M.; Moura, A.A. Spermatozoa and seminal plasma proteomics: Too many molecules, too few markers. The case of bovine and porcine semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 247, 107075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafzadeh, A.; Karsani, S.A.; Nathan, S. Mammalian sperm fertility related proteins. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 10, 1649–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- O’Flaherty, C. Peroxiredoxin 6: The Protector of Male Fertility. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.B. Peroxiredoxin 6 in the repair of peroxidized cell membranes and cell signalling. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 617, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Do, H.L.; Chandimali, N.; Lee, S.B.; Mok, Y.S.; Kim, N.; Kim, S.B.; Kwon, T.; Jeong, D.K. Non-thermal plasma treatment improves chicken sperm motility via the regulation of demethylation levels. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moawad, A.R.; Fernandez, M.C.; Scarlata, E.; Dodia, C.; Feinstein, S.I.; Fisher, A.B.; O’Flaherty, C. Deficiency of peroxiredoxin 6 or inhibition of its phospholipase A2 activity impair the in vitro sperm fertilizing competence in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhoberac, B.B.; Vidal, R. Iron, ferritin, hereditary ferritinopathy, and neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Yuge, M.; Uda, A.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Orino, K. Structural and functional analyses of chicken liver ferritin. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolea, F.; Biamonte, F.; Candeloro, P.; Di Sanzo, M.; Cozzi, A.; Di Vito, A.; Quaresima, B.; Lobello, N.; Trecroci, F.; Di Fabrizio, E. H ferritin silencing induces protein misfolding in K562 cells: A Raman analysis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirè, A.; Cianfruglia, L.; Minnelli, C.; Romaldi, B.; Laudadio, E.; Galeazzi, R.; Antognelli, C.; Armeni, T. Glyoxalase 2: Towards a Broader View of the Second Player of the Glyoxalase System. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, M.R.; Hedges, S.B. Evolutionary history of the enolase gene family. Gene 2000, 259, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Wang, J.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Lian, S.; Guo, W.; Yang, H.; Kong, F.; Zhen, L.; Guo, L.; et al. Progress in the biological function of alpha-enolase. Anim. Nutr. 2016, 2, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graven, K.K.; Zimmerman, L.H.; Dickson, E.W.; Weinhouse, G.L.; Farber, H.W. Endothelial cell hypoxia associated proteins are cell and stress specific. J. Cell Physiol. 1993, 157, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, G.J. Maintenance of ATP concentrations in and of fertilizing ability of fowl and turkey spermatozoa in vitro. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1982, 66, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernansanz-Agustín, P.; Izquierdo-Álvarez, A.; Sánchez-Gómez, F.J.; Ramos, E.; Villa-Piña, T.; Lamas, S.; Bogdanova, A.; Martínez-Ruiz, A. Acute hypoxia produces a superoxide burst in cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 71, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.A.; Elliott, T.J. Stress proteins, infection, and immune surveillance. Cell 1989, 59, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucker, D.S.; Jain, M.R.; Pattabiraman, G.; Palasiewicz, K.; Birge, R.B.; Li, H. Externalized glycolytic enzymes are novel, conserved, and early biomarkers of apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 10325–10343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarsono, T.; Supriatna, I.; Setiadi, M.A.; Agil, M.; Purwantara, B. Detection of Plasma Membrane Alpha Enolase (ENO1) and Its Relationship with Sperm Quality of Bali Cattle. Trop. Anim. Sci. J. 2023, 46, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, A.R. Role for Beta 2 Microglobulin in Speciation. In Protides of the Biological Fluids; Peeters, H., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985; Volume 32, pp. 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Tang, F.; Wang, J.; Yang, J.Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.F.; Li, Z.Q. Serum beta2-microglobulin acts as a biomarker for severity and prognosis in glioma patients: A preliminary clinical study. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizana, J.; Eneroth, P.; Byström, B.; Bygdeman, M. Seminal Plasma Levels of Beta2-Microglobulin and Cea-Like Protein in Infertility. In Protides of the Biological Fluids; Peeters, H., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; Volume 29, pp. 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chard, T.; Parslow, J.; Rehmann, T.; Dawnay, A. The concentrations of transferrin, β2-microglobulin, and albumin in seminal plasma in relation to sperm count. Fertil. Steril. 1991, 55, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Han, X.; Yuan, J.; Ma, L.; Ma, H.; Chen, J. Mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase (GOT2) protein as a potential cryodamage biomarker in rooster spermatozoa cryopreservation. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuhashi, M.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Fatty Acid-Binding Proteins: Role in Metabolic Diseases and Potential as Drug Targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008, 7, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkoe, T.M.; Mechtler, T.P.; Weninger, M.; Pones, M.; Rebhandl, W.; Kasper, D.C. Serum Levels of Interleukin-8 and Gut-Associated Biomarkers in Diagnosing Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Preterm Infants. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 49, 1446–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Kagawa, Y.; Miyazaki, H.; Shil, S.K.; Umaru, B.A.; Yasumoto, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Owada, Y. FABP7 Protects Astrocytes Against ROS Toxicity via Lipid Droplet Formation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 5763–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, R.A.; Thurston, R.J.; Biellier, H.V. Morphology of the epididymal region of turkeys producing abnormal yellow semen. Poult. Sci. 1982, 61, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atikuzzaman, M.; Sanz, L.; Pla, D.; Alvarez-Rodriguez, M.; Rubér, M.; Wright, D.; Calvete, J.J.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H. Selection for higher fertility reflects in the seminal fluid proteome of modern domestic chicken. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2017, 21, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.V.; Soler, L.; Thélie, A.; Grasseau, I.; Cordeiro, L.; Tomas, D.; Teixeira-Gomes, A.P.; Labas, V.; Blesblois, E. Proteomic Changes Associated with Sperm Fertilizing Ability in Meat-Type Roosters. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 655866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenol, A.; Delezie, E.; Wang, Y.; Franssens, L.; Willems, E.; Ampe, B.; Everaert, N. Effects of maternal dietary EPA and DHA supplementation and breeder age on embryonic and post-hatch performance of broiler offspring. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2015, 99, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.D.; Lorenz, F.W.; Asmundson, V.S. Semen Production in the Turkey Male: 2. Age at Sexual Maturity. Poult. Sci. 1955, 34, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, D.; Paudel, S.; Sapkota, S.; Shrestha, S.; Poudel, N.; Bhattari, N. Performance of egg production, fertility and hatchability of turkey in different production systems. J. Nepal Agric. Res. Counc. 2024, 10, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, W.H.; Quinn, J.P. The collection of spermatozoa from the domestic fowl and turkey. Poult. Sci. 1937, 16, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.L.; Johnson, L.A. Viability Assessment of Mammalian sperm using SYBR-14 and propidium iodide. Biol. Reprod. 1995, 53, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampiao, F.; Strijdom, H.; du Plessis, S.S. Direct nitric oxide measurement in human spermatozoa: Flow cytometric analysis using the fluorescent probe, diaminofluorescein. Int. J. Androl. 2006, 29, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampugnani, L.; Maccheroni, M. Rapid colorimetry of zinc in seminal fluid. Clin. Chem. 1984, 30, 1366–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | GF | IF | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sperm concentration (×109) | 4.7 ± 1.0 * | 5.6 ± 1.7 * | 0.022 |

| PMI (%) | 88.4 ± 4.6 ** | 78.4 ± 6.8 ** | 0.000 |

| MMP (%) | 79.7 ± 6.2 | 79.9 ± 7.9 | 0.637 |

| NO (%) | 29.3 ± 11.2 * | 42.4 ± 19.0 * | 0.044 |

| TMOT (%) | 81.2 ± 6.6 * | 71.7 ± 8.5 * | 0.002 |

| PMOT (%) | 49.7 ± 13.2 | 46.3 ± 24.6 | 0.672 |

| VAP (µm/s) | 74.0 ± 3.7 | 80.3 ± 13.3 | 0.148 |

| VSL (µm/s) | 70.7 ± 5.4 | 73.9 ± 15.0 | 0.209 |

| VCL (µm/s) | 116.8 ± 8.9 * | 105.9 ± 14.4 * | 0.028 |

| ALH (µm) | 3.59 ± 0.5 | 3.29 ± 0.6 | 0.146 |

| BCF (Hz) | 22.4 ±8.3 | 18.7 ± 6.8 | 0.150 |

| STR (%) | 81.6 ± 6.0 ** | 90.3 ± 5.3 ** | 0.000 |

| LIN (%) | 66.7 ± 6.3 | 71.7 ± 8.5 | 0.125 |

| Parameters | GF | IF | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total protein (mg/mL) | 7.9 ± 2.0 ** | 5.6 ± 1.4 ** | 0.000 |

| SOD activity (U/mL) | 2.4 ± 0.6 ** | 1.1 ± 0.4 ** | 0.000 |

| GPx activity (U/mL) | 0.4 ± 0.1 ** | 0.2 ± 0.1 ** | 0.001 |

| CAT activity (µM/min/mL) | 14.4 ± 10.3 * | 39.2 ± 29.9 * | 0.014 |

| GSH (M/mL) | 0.5 ± 0.02 ** | 0.9 ± 0.03 ** | 0.000 |

| MDA (µM/mL) | 11.5 ± 11.7 ** | 28.4 ± 12.2 ** | 0.000 |

| Zn2+ (µg/mL) | 151.9 ± 58.9 ** | 49.7 ± 24.6 ** | 0.000 |

| Parameters | GF | IF | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOD activity (U/mL) | 0.6 ± 0.2 ** | 1.2 ± 0.5 ** | 0.001 |

| GPx activity (U/mL) | 0.4 ± 0.1 ** | 0.2 ± 0.2 ** | 0.000 |

| CAT activity (µM/min/mL) | 114.3 ± 59.4 * | 70.1 ± 44.5 * | 0.012 |

| GSH (M/109 sperm) | 0.2 ± 0.08 ** | 0.1 ± 0.07 ** | 0.000 |

| MDA (µM/109 sperm) | 6.1 ± 4.3 ** | 14.8 ± 6.1 ** | 0.000 |

| Zn2+ (µg/109 sperm) | 43.6 ± 12.1 * | 92.2 ± 64.3 * | 0.018 |

| Protein [kDa] | GF | IF |

|---|---|---|

| 107 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.37 ± 0.03 |

| 80 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.01 |

| 49 | 0.30 ± 0.02 | 0.35 ± 0.01 |

| 41 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 0.01 |

| 29 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.02 |

| 26 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.02 |

| 25 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.01 |

| 18 | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.04 |

| 16 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.25 ± 0.02 |

| 12 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| Protein [kDa] | GF | IF |

|---|---|---|

| 107 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.01 |

| 52 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| 49 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 0.68 ± 0.01 |

| 41 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.59 ± 0.01 |

| 29 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.03 |

| 25 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| 18 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.02 |

| 16 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orzołek, A.; Dziekońska, A.; Skorynko, P.; Ner-Kluza, J. Can the Quality of Semen Affect the Fertilisation Indices of Turkey Eggs? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211000

Orzołek A, Dziekońska A, Skorynko P, Ner-Kluza J. Can the Quality of Semen Affect the Fertilisation Indices of Turkey Eggs? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211000

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrzołek, Aleksandra, Anna Dziekońska, Paulina Skorynko, and Joanna Ner-Kluza. 2025. "Can the Quality of Semen Affect the Fertilisation Indices of Turkey Eggs?" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211000

APA StyleOrzołek, A., Dziekońska, A., Skorynko, P., & Ner-Kluza, J. (2025). Can the Quality of Semen Affect the Fertilisation Indices of Turkey Eggs? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211000