A Role of Inflammation in Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disorders—In a Perspective of Treatment?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Presence of Inflammatory Process in the Patients Affected by CMT

3. The Role of Inflammation Process in the Mice Models of CMT

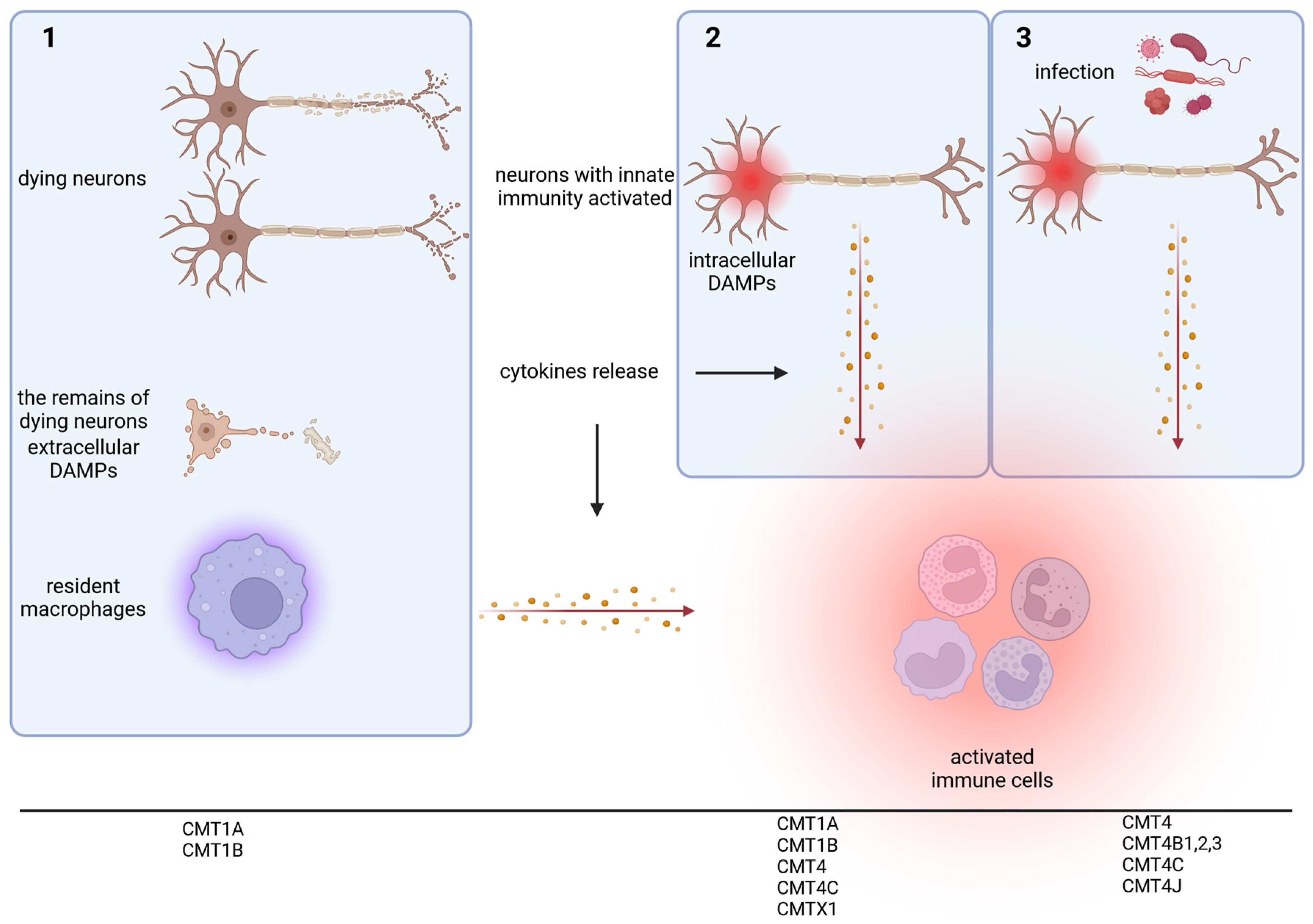

4. The Molecular Changes That Could Lead to Inflammation in Selected CMT Types

5. A Perspective on Anti-Inflammatory Treatment in CMTs—Which Patients Should Be Treated and When?

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barreto, L.C.; Oliveira, F.S.; Nunes, P.S.; de França Costa, I.M.; Garcez, C.A.; Goes, G.M.; Neves, E.L.; de Souza Siqueira Quintans, J.; de Souza Araújo, A.A. Epidemiologic Study of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Systematic Review. Neuroepidemiology 2016, 46, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skre, H. Genetic and clinical aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth’s disease. Clin. Genet. 1974, 6, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipis, M.; Rossor, A.M.; Laura, M.; Reilly, M.M. Next-generation sequencing in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: Opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisciotta, C.; Pareyson, D. Gene therapy and other novel treatment approaches for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2023, 33, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, Y.; Takashima, H. The Current State of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Treatment. Genes 2023, 14, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, M.; Sargiannidou, I.; Georgiou, E.; Kagiava, A.; Kleopa, K.A. Emerging Therapies for Charcot-Marie-Tooth Inherited Neuropathies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossor, A.M.; Shy, M.E.; Reilly, M.M. Are we prepared for clinical trials in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease? Brain Res. 2020, 1729, 146625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorcio-Bezerra, M.L.; Pinto, W.B.V.R.; Bichuetti, D.B.; Souza, P.V.S.; Nunes, R.M.; Silva, L.H.L.; Lima, K.D.F.; Manzano, G.M.; Oliveira, A.S.B.; Baeta, A.M. Immune-mediated inflammatory polyneuropathy overlapping Charcot-Marie-Tooth 1B. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 75, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaghy, M.; Sisodiya, S.M.; Kennett, R.; McDonald, B.; Haites, N.; Bell, C. Steroid responsive polyneuropathy in a family with a novel myelin protein zero mutation. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2000, 69, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauw, F.; Fargeot, G.; Adams, D.; Attarian, S.; Cauquil, C.; Chanson, J.B.; Créange, A.; Gendre, T.; Deiva, K.; Delmont, E.; et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease misdiagnosed as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: An international multicentric retrospective study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 2846–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Garcia, M.A.; Stettner, G.M.; Kinali, M.; Clarke, A.; Fallon, P.; Knirsch, U.; Wraige, E.; Jungbluth, H. Genetic neuropathies presenting with CIDP-like features in childhood. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2021, 31, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potulska-Chromik, A.; Ryniewicz, B.; Aragon-Gawinska, K.; Kabzinska, D.; Seroka, A.; Lipowska, M.; Kaminska, A.M.; Kostera-Pruszczyk, A. Are electrophysiological criteria useful in distinguishing childhood demyelinating neuropathies? J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2016, 21, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg, L.; Malik, O.; Kenton, A.R.; Sharp, D.; Muddle, J.R.; Davis, M.B.; Winer, J.B.; Orrell, R.W.; King, R.H. Coexistent hereditary and inflammatory neuropathy. Brain 2004, 127, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malandrini, A.; Villanova, M.; Dotti, M.T.; Federico, A. Acute inflammatory neuropathy in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neurology 1999, 52, 859–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlden, H.; Laura, M.; Ginsberg, L.; Jungbluth, H.; Robb, S.A.; Blake, J.; Robinson, S.; King, R.H.; Reilly, M.M. The phenotype of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4C due to SH3TC2 mutations and possible predisposition to an inflammatory neuropathy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2009, 19, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, C.K.; Freidin, M. GJB1-associated X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, a disorder affecting the central and peripheral nervous systems. Cell Tissue Res. 2015, 360, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weishaupt, J.H.; Ganser, C.; Bähr, M. Inflammatory demyelinating CNS disorder in a case of X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: Positive response to natalizumab. J. Neurol. 2012, 259, 1967–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottenie, E.; Menezes, M.P.; Rossor, A.M.; Morrow, J.M.; Yousry, T.A.; Dick, D.J.; Anderson, J.R.; Jaunmuktane, Z.; Brandner, S.; Blake, J.C.; et al. Rapidly progressive asymmetrical weakness in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4J resembles chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2013, 23, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloribi-Djefaflia, S.; Morales, R.J.; Fatehi, F.; Isapof, A.; Servais, L.; Leonard-Louis, S.; Michaud, M.; Verdure, P.; Gidaro, T.; Pouget, J.; et al. Clinical and genetic features of patients suffering from CMT4J. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turčanová Koprušáková, M.; Grofik, M.; Kantorová, E.; Jungová, P.; Chandoga, J.; Kolisek, M.; Valkovič, P.; Škorvánek, M.; Ploski, R.; Kurča, E.; et al. Atypical presentation of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1C with a new mutation: A case report. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, H.S.; Kwon, H.M.; Kim, J.; Nam, S.H.; Jung, N.Y.; Lee, A.J.; Jung, Y.H.; Kim, S.B.; Chung, K.W.; et al. Identification and clinical characterization of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1C patients with LITAF p.G112S mutation. Genes Genom. 2022, 44, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potulska-Chromik, A.; Sinkiewicz-Darol, E.; Kostera-Pruszczyk, A.; Drac, H.; Kabzińska, D.; Zakrzewska-Pniewska, B.; Gołębiowski, M.; Kochański, A. Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1C disease coexisting with progressive multiple sclerosis: A study of an overlapping syndrome. Folia Neuropathol. 2012, 50, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrou, M.; Kleopa, K.A. CMT1A current gene therapy approaches and promising biomarkers. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 1434–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrou, M.; Kagiava, A.; Choudury, S.G.; Jennings, M.J.; Wallace, L.M.; Fowler, A.M.; Heslegrave, A.; Richter, J.; Tryfonos, C.; Christodoulou, C.; et al. A translatable RNAi-driven gene therapy silences PMP22/Pmp22 genes and improves neuropathy in CMT1A mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e159814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shy, M.E.; Arroyo, E.; Sladky, J.; Menichella, D.; Jiang, H.; Xu, W.; Kamholz, J.; Scherer, S.S. Heterozygous P0 knockout mice develop a peripheral neuropathy that resembles chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP). J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1997, 56, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, R. P0-Deficient Knockout Mice as Tools to Understand Pathomechanisms in Charcot-Marie-Tooth 1B and P0-Related Déjérine-Sottas Syndrome. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 883, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, C.D.; Stienekemeier, M.; Oehen, S.; Bootz, F.; Zielasek, J.; Gold, R.; Toyka, K.V.; Schachner, M.; Martini, R. Immune deficiency in mouse models for inherited peripheral neuropathies leads to improved myelin maintenance. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, R.; Zielasek, J.; Toyka, K.V.; Giese, K.P.; Schachner, M. Protein zero (P0)-deficient mice show myelin degeneration in peripheral nerves characteristic of inherited human neuropathies. Nat. Genet. 1995, 11, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäurer, M.; Schmid, C.D.; Bootz, F.; Zielasek, J.; Toyka, K.V.; Oehen, S.; Martini, R. Bone marrow transfer from wild-type mice reverts the beneficial effect of genetically mediated immune deficiency in myelin mutants. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2001, 17, 1094–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carenini, S.; Mäurer, M.; Werner, A.; Blazyca, H.; Toyka, K.V.; Schmid, C.D.; Raivich, G.; Martini, R. The role of macrophages in demyelinating peripheral nervous system of mice heterozygously deficient in p0. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 152, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobsar, I.; Mäurer, M.; Ott, T.; Martini, R. Macrophage-related demyelination in peripheral nerves of mice deficient in the gap junction protein connexin 32. Neurosci. Lett. 2002, 320, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagiava, A.; Karaiskos, C.; Lapathitis, G.; Heslegrave, A.; Sargiannidou, I.; Zetterberg, H.; Bosch, A.; Kleopa, K.A. Gene replacement therapy in two Golgi-retained CMT1X mutants before and after the onset of demyelinating neuropathy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2023, 30, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagiava, A.; Karaiskos, C.; Richter, J.; Tryfonos, C.; Lapathitis, G.; Sargiannidou, I.; Christodoulou, C.; Kleopa, K.A. Intrathecal gene therapy in mouse models expressing CMT1X mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 1460–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olympiou, M.; Sargiannidou, I.; Markoullis, K.; Karaiskos, C.; Kagiava, A.; Kyriakoudi, S.; Abrams, C.K.; Kleopa, K.A. Systemic inflammation disrupts oligodendrocyte gap junctions and induces ER stress in a model of CNS manifestations of X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D.; Patzkó, Á.; Schreiber, D.; van Hauwermeiren, A.; Baier, M.; Groh, J.; West, B.L.; Martini, R. Targeting the colony stimulating factor 1 receptor alleviates two forms of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease in mice. Brain 2015, 138, 3193–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaneophytou, C.P.; Georgiou, E.; Karaiskos, C.; Sargiannidou, I.; Markoullis, K.; Freidin, M.M.; Abrams, C.K.; Kleopa, K.A. Regulatory role of oligodendrocyte gap junctions in inflammatory demyelination. Glia 2018, 66, 2589–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groh, J.; Weis, J.; Zieger, H.; Stanley, E.R.; Heuer, H.; Martini, R. Colony-stimulating factor-1 mediates macrophage-related neural damage in a model for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1X. Brain 2012, 135, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagiava, A.; Richter, J.; Tryfonos, C.; Karaiskos, C.; Heslegrave, A.J.; Sargiannidou, I.; Rossor, A.M.; Zetterberg, H.; Reilly, M.M.; Christodoulou, C.; et al. Gene replacement therapy after neuropathy onset provides therapeutic benefit in a model of CMT1X. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 3528–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagiava, A.; Karaiskos, C.; Richter, J.; Tryfonos, C.; Jennings, M.J.; Heslegrave, A.J.; Sargiannidou, I.; Stavrou, M.; Zetterberg, H.; Reilly, M.M.; et al. AAV9-mediated Schwann cell-targeted gene therapy rescues a model of demyelinating neuropathy. Gene Ther. 2021, 28, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Lizarbe, S.; Civera-Tregón, A.; Cantarero, L.; Herrer, I.; Juarez, P.; Hoenicka, J.; Palau, F. Neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease caused by lack of GDAP1. Exp. Neurol. 2019, 320, 113004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, K.; Nógrádi, B.; Kristóf, R.; Mészáros, Á.; Pajer, K.; Siklós, L.; Nógrádi, A.; Wilhelm, I.; Krizbai, I.A. Motoneuronal inflammasome activation triggers excessive neuroinflammation and impedes regeneration after sciatic nerve injury. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yum, S.W.; Kleopa, K.A.; Shumas, S.; Scherer, S.S. Diverse trafficking abnormalities of connexin32 mutants causing CMTX. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002, 11, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanemann, C.O.; D’Urso, D.; Gabreëls-Festen, A.A.; Müller, H.W. Mutation-dependent alteration in cellular distribution of peripheral myelin protein 22 in nerve biopsies from Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1A. Brain 2000, 123 Pt 5, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shames, I.; Fraser, A.; Colby, J.; Orfali, W.; Snipes, G.J. Phenotypic differences between peripheral myelin protein-22 (PMP22) and myelin protein zero (P0) mutations associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth-related diseases. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2003, 62, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, A.B.; Mercado, E.L.; Hoffmann, A.; Niwa, M. ER stress activates NF-κB by integrating functions of basal IKK activity, IRE1 and PERK. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, S.Z.; Lourie, R.; Das, I.; Chen, A.C.; McGuckin, M.A. The interplay between endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl, H.L.; Baeuerle, P.A. Activation of NF-kappa B by ER stress requires both Ca2+ and reactive oxygen intermediates as messengers. FEBS Lett. 1996, 392, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R.C.; Peden, A.A.; Buss, F.; Bright, N.A.; Latouche, M.; Reilly, M.M.; Kendrick-Jones, J.; Luzio, J.P. Mistargeting of SH3TC2 away from the recycling endosome causes Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4C. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, S.; Chiu, M.; Dacks, J.B.; Roberts, R.C. Exclusive expression of the Rab11 effector SH3TC2 in Schwann cells links integrin-α6 and myelin maintenance to Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathan-Kumar, S.; Roland, J.T.; Momoh, M.; Goldstein, A.; Lapierre, L.A.; Manning, E.; Mitchell, L.; Norman, J.; Kaji, I.; Goldenring, J.R. Rab11FIP1-deficient mice develop spontaneous inflammation and show increased susceptibility to colon damage. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2022, 323, G239–G254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonugunta, V.K.; Sakai, T.; Pokatayev, V.; Yang, K.; Wu, J.; Dobbs, N.; Yan, N. Trafficking-Mediated STING Degradation Requires Sorting to Acidified Endolysosomes and Can Be Targeted to Enhance Anti-tumor Response. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 3234–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, P.; Rivara, S.; Liu, C.; Ricci, J.; Ren, X.; Hurley, J.H.; Ablasser, A. Clathrin-associated AP-1 controls termination of STING signalling. Nature 2022, 610, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balka, K.R.; Venkatraman, R.; Saunders, T.L.; Shoppee, A.; Pang, E.S.; Magill, Z.; Homman-Ludiye, J.; Huang, C.; Lane, R.M.; York, H.M.; et al. Termination of STING responses is mediated via ESCRT-dependent degradation. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e112712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Craene, J.O.; Bertazzi, D.L.; Bär, S.; Friant, S. Phosphoinositides, Major Actors in Membrane Trafficking and Lipid Signaling Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyn, C.; Li, J. Fig4 deficiency: A newly emerged lysosomal storage disorder? Prog. Neurobiol. 2013, 101, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dowling, J.J.; Jin, N.; Adamska, M.; Shiga, K.; Szigeti, K.; Shy, M.E.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Mutation of FIG4 causes neurodegeneration in the pale tremor mouse and patients with CMT4J. Nature 2007, 448, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, I.; Dina, G.; Tronchère, H.; Kaufman, E.; Chicanne, G.; Cerri, F.; Wrabetz, L.; Payrastre, B.; Quattrini, A.; Weisman, L.S.; et al. Genetic interaction between MTMR2 and FIG4 phospholipid phosphatases involved in Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathies. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katona, I.; Zhang, X.; Bai, Y.; Shy, M.E.; Guo, J.; Yan, Q.; Hatfield, J.; Kupsky, W.J.; Li, J. Distinct pathogenic processes between Fig4-deficient motor and sensory neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011, 33, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chow, C.Y.; Sahenk, Z.; Shy, M.E.; Meisler, M.H.; Li, J. Mutation of FIG4 causes a rapidly progressive, asymmetric neuronal degeneration. Brain 2008, 131, 1990–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chen, C.; Mei, C.; Liu, S.; Xiang, C.; Fang, W.; Zhang, F.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Innate immune sensing of lysosomal dysfunction drives multiple lysosomal storage disorders. Nat. Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenk, G.M.; Szymanska, K.; Debska-Vielhaber, G.; Rydzanicz, M.; Walczak, A.; Bekiesinska-Figatowska, M.; Vielhaber, S.; Hallmann, K.; Stawinski, P.; Buehring, S.; et al. Biallelic Mutations of VAC14 in Pediatric-Onset Neurological Disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 99, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantarero, L.; Juárez-Escoto, E.; Civera-Tregón, A.; Rodríguez-Sanz, M.; Roldán, M.; Benítez, R.; Hoenicka, J.; Palau, F. Mitochondria-lysosome membrane contacts are defective in GDAP1-related Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2021, 29, 3589–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León, M.; Prieto, J.; Molina-Navarro, M.M.; García-García, F.; Barneo-Muñoz, M.; Ponsoda, X.; Sáez, R.; Palau, F.; Dopazo, J.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C.; et al. Rapid degeneration of iPSC-derived motor neurons lacking Gdap1 engages a mitochondrial-sustained innate immune response. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binięda, K.; Rzepnikowska, W.; Kolakowski, D.; Kaminska, J.; Szczepankiewicz, A.A.; Nieznańska, H.; Kochański, A.; Kabzińska, D. Mutations in GDAP1 Influence Structure and Function of the Trans-Golgi Network. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Z.J. PtdIns4P on dispersed trans-Golgi network mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2018, 564, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Marciano, D.L.; Leeman, S.E.; Amar, S. LPS induces the interaction of a transcription factor, LPS-induced TNF-alpha factor, and STAT6(B) with effects on multiple cytokines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5132–5137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myokai, F.; Takashiba, S.; Lebo, R.; Amar, S. A novel lipopolysaccharide-induced transcription factor regulating tumor necrosis factor alpha gene expression: Molecular cloning, sequencing, characterization, and chromosomal assignment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 4518–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Guariglia, S.; Yu, R.Y.; Li, W.; Brancho, D.; Peinado, H.; Lyden, D.; Salzer, J.; Bennett, C.; Chow, C.W. Mutation of SIMPLE in Charcot-Marie-Tooth 1C alters production of exosomes. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 1619–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, X.; Brancho, D.; Liang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Bennett, C.; Chow, C.W. Dysregulated Inflammatory Signaling upon Charcot-Marie-Tooth Type 1C Mutation of SIMPLE Protein. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 35, 2464–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, J.R.; Ho, A.K.; Laurá, M.; Horvath, R.; Reilly, M.M.; Luzio, J.P.; Roberts, R.C. A dysfunctional endolysosomal pathway common to two sub-types of demyelinating Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirk, A.J.; Anderson, S.K.; Hashemi, S.H.; Chance, P.F.; Bennett, C.L. SIMPLE interacts with NEDD4 and TSG101: Evidence for a role in lysosomal sorting and implications for Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2005, 82, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Cantó, M.E.; Patel, N.; Velasco-Aviles, S.; Casillas-Bajo, A.; Salas-Felipe, J.; García-Escrivá, A.; Díaz-Marín, C.; Cabedo, H. Novel EGR2 variant that associates with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease when combined with lipopolysaccharide-induced TNF-α factor T49M polymorphism. Neurol. Genet. 2020, 6, e407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabzińska, D.; Chabros, K.; Kamińska, J.; Kochański, A. The GDAP1 p.Glu222Lys Variant-Weak Pathogenic Effect, Cumulative Effect of Weak Sequence Variants, or Synergy of Both Factors? Genes 2022, 13, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, L.; Huang, S.; Zhao, H.; Wang, B.; Cao, W.; Hu, Z.; Guo, J.; et al. One PMP22/MPZ and Three MFN2/GDAP1 Concomitant Variants Occurred in a Cohort of 189 Chinese Charcot-Marie-Tooth Families. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 736704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostera-Pruszczyk, A.; Kosinska, J.; Pollak, A.; Stawinski, P.; Walczak, A.; Wasilewska, K.; Potulska-Chromik, A.; Szczudlik, P.; Kaminska, A.; Ploski, R. Exome sequencing reveals mutations in MFN2 and GDAP1 in severe Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2014, 19, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CMT Type | Mutated Gene | Protein | Inflammation in Patients | Inflammation in Mice Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMT1A | PMP22 | PMP22 (Peripheral Myelin Protein 22) | [10,11,13,14] | [24] |

| CMT1B | MPZ | P0 (Myelin Protein Zero) | [8,10,11] | [25,26,30] |

| CMT1C | LITAF | LITAF (Lipopolysaccharide-Induced TNF Factor) | [20,21,22] | |

| CMTX1 | GJB1 | Cx32 (Connexin32) | [10,13,16] | [31,32,38] |

| CMT4 | GDAP1 | GDAP1 (Ganglioside Induced Differentiation Associated Protein 1) | [40] | |

| CMT4C | SH3TC2 | SH3TC2 (SH3 Domain And Tetratricopeptide Repeats 2) | [10,11,15,17] | |

| CMT4J | FIG4 | FIG4 | [18,19] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamińska, J.; Kochański, A. A Role of Inflammation in Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disorders—In a Perspective of Treatment? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26010015

Kamińska J, Kochański A. A Role of Inflammation in Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disorders—In a Perspective of Treatment? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamińska, Joanna, and Andrzej Kochański. 2025. "A Role of Inflammation in Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disorders—In a Perspective of Treatment?" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26010015

APA StyleKamińska, J., & Kochański, A. (2025). A Role of Inflammation in Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disorders—In a Perspective of Treatment? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26010015