Study on the Effects of Angiotensin Receptor/Neprilysin Inhibitors on Renal Haemodynamics in Healthy Dogs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

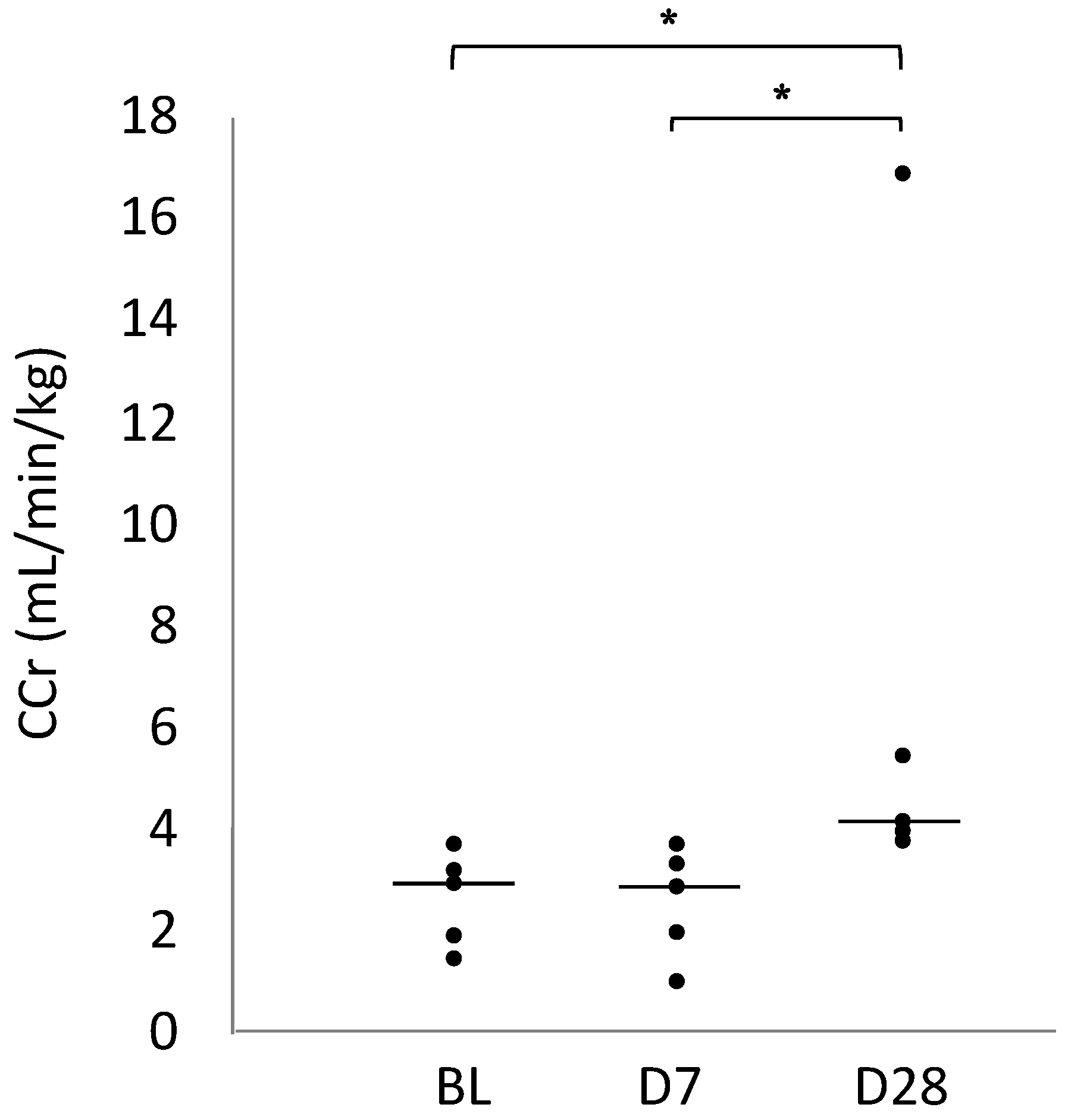

2.1. Creatinine Clearance (CCr)

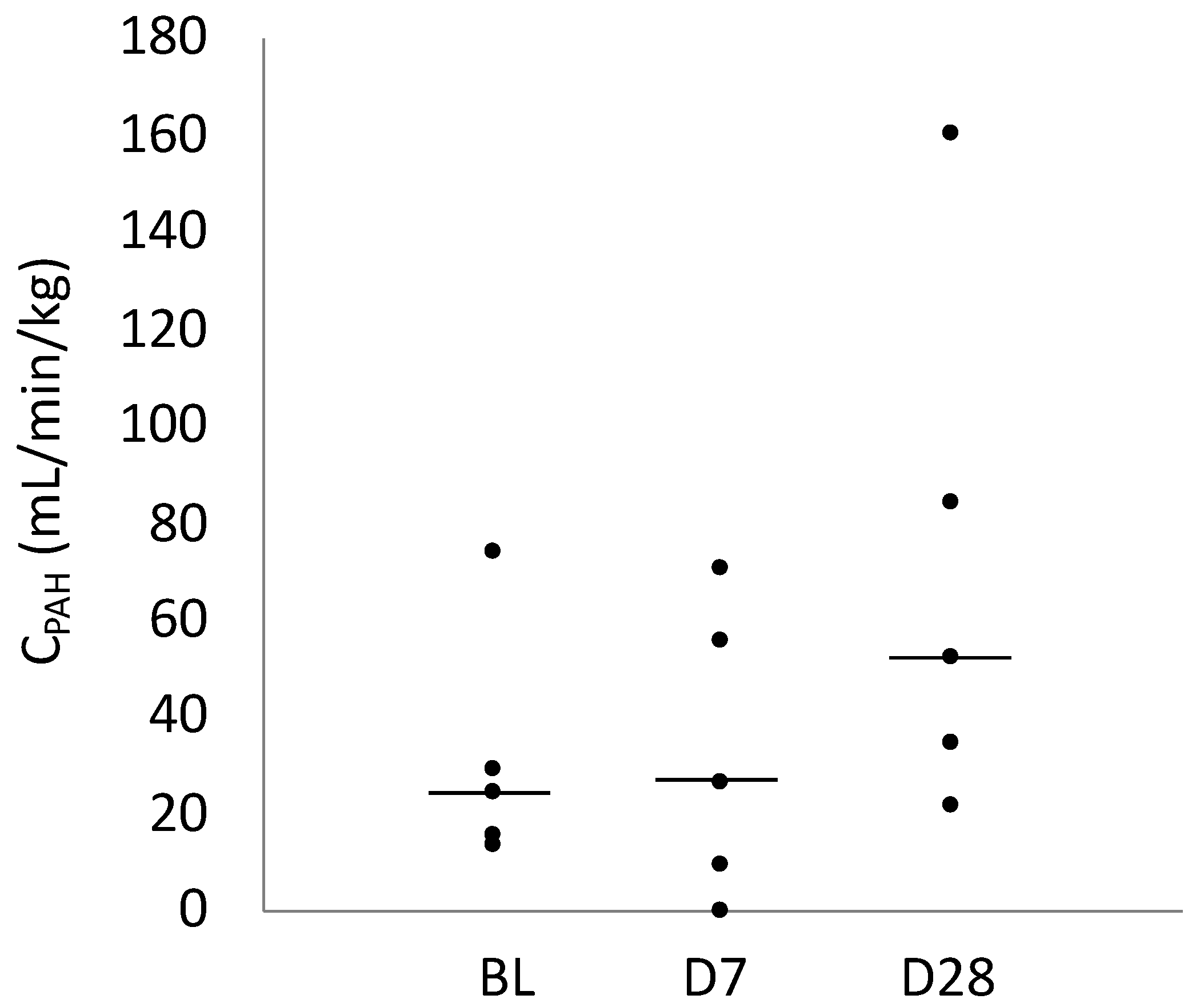

2.2. CPAH

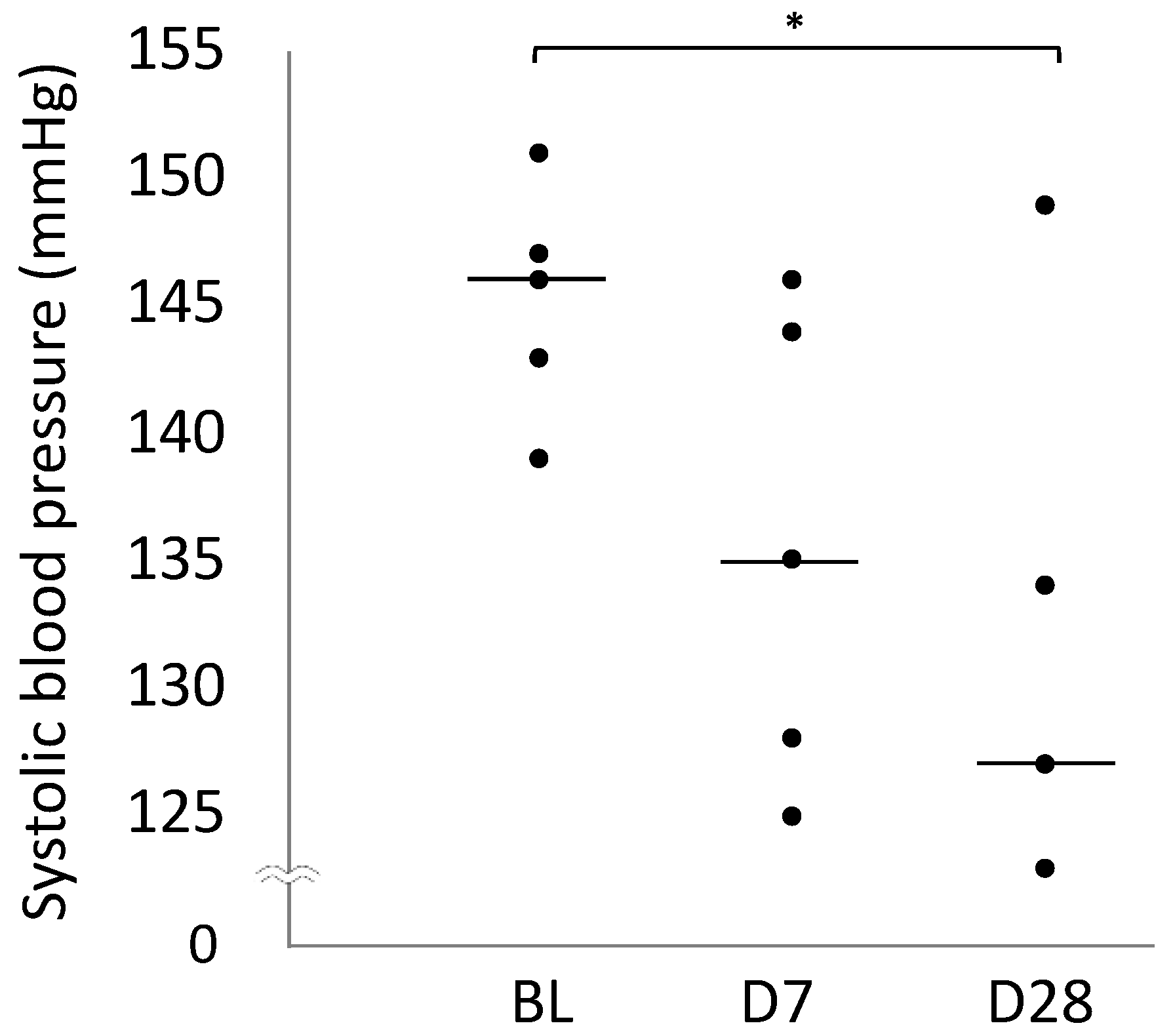

2.3. Blood Pressure

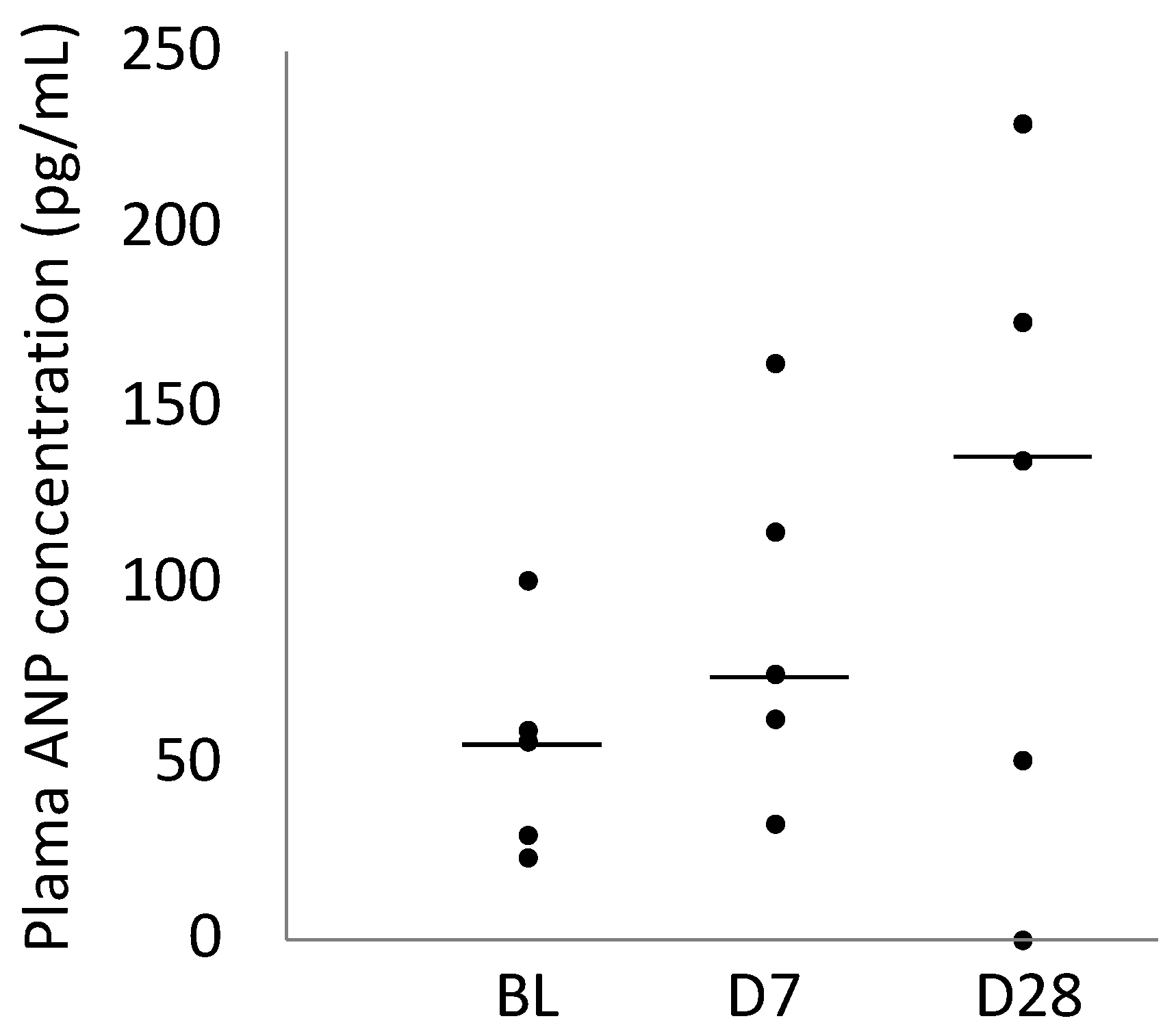

2.4. Plasma ANP Concentration

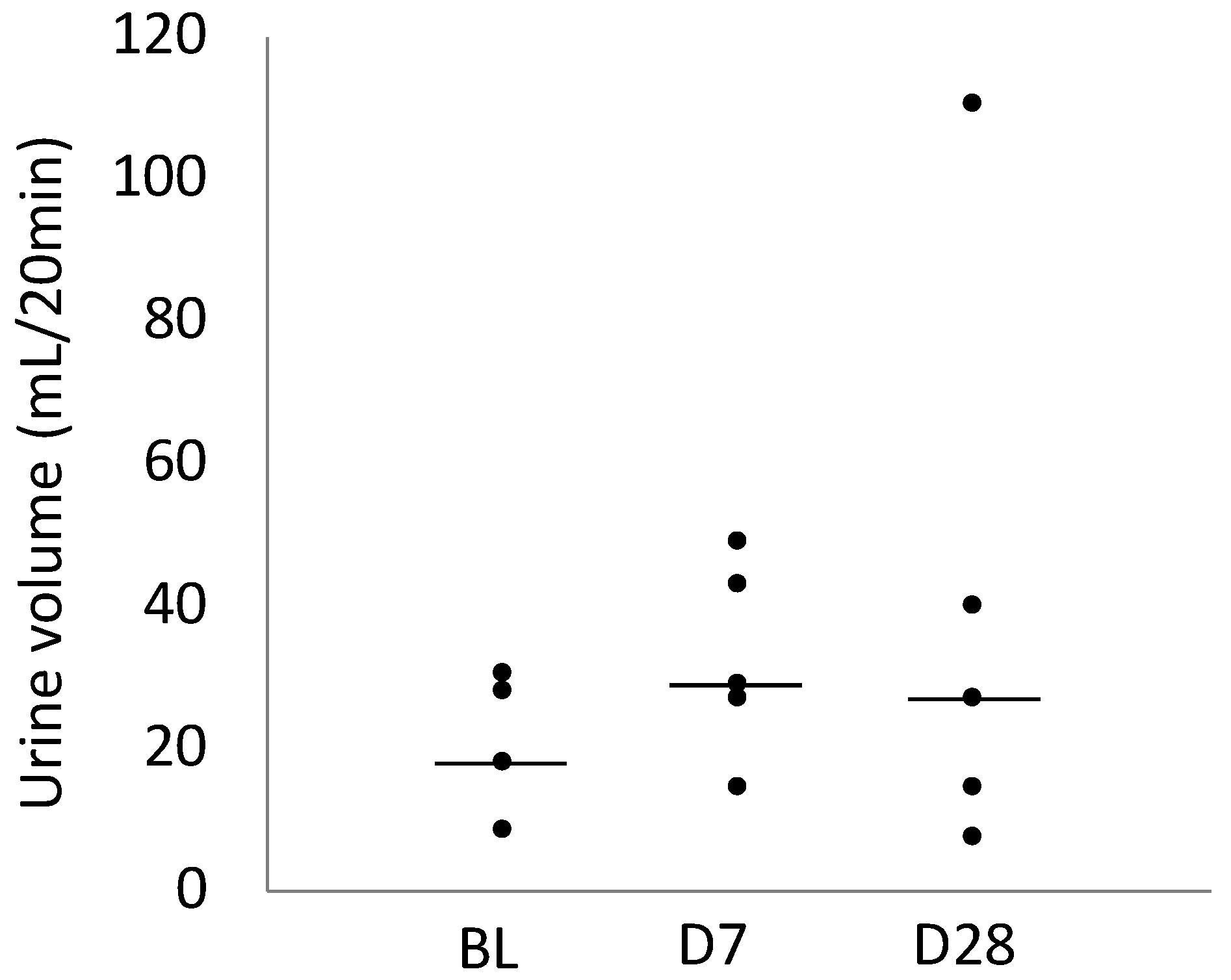

2.5. Urine Volume

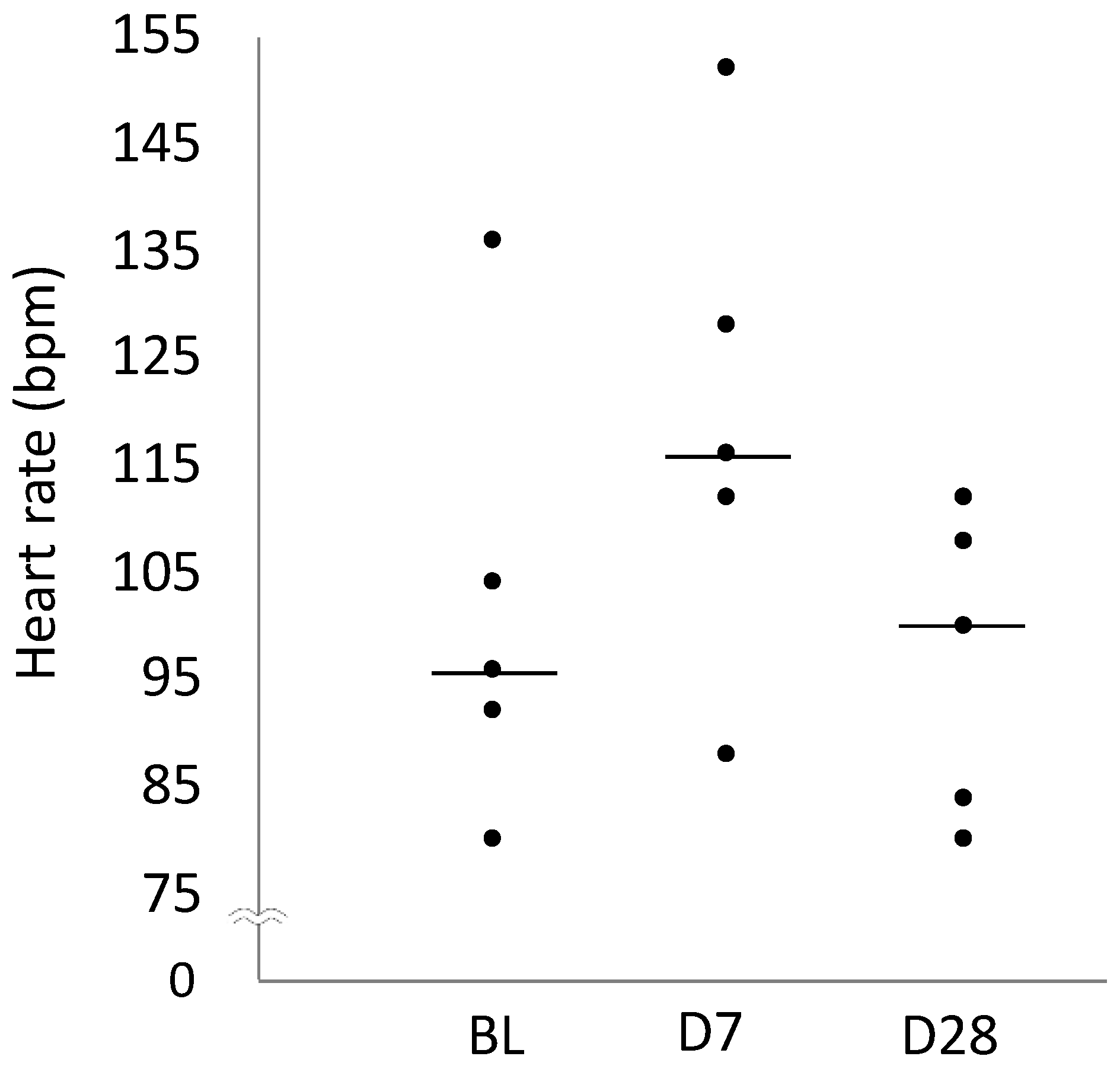

2.6. Heart Rate

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

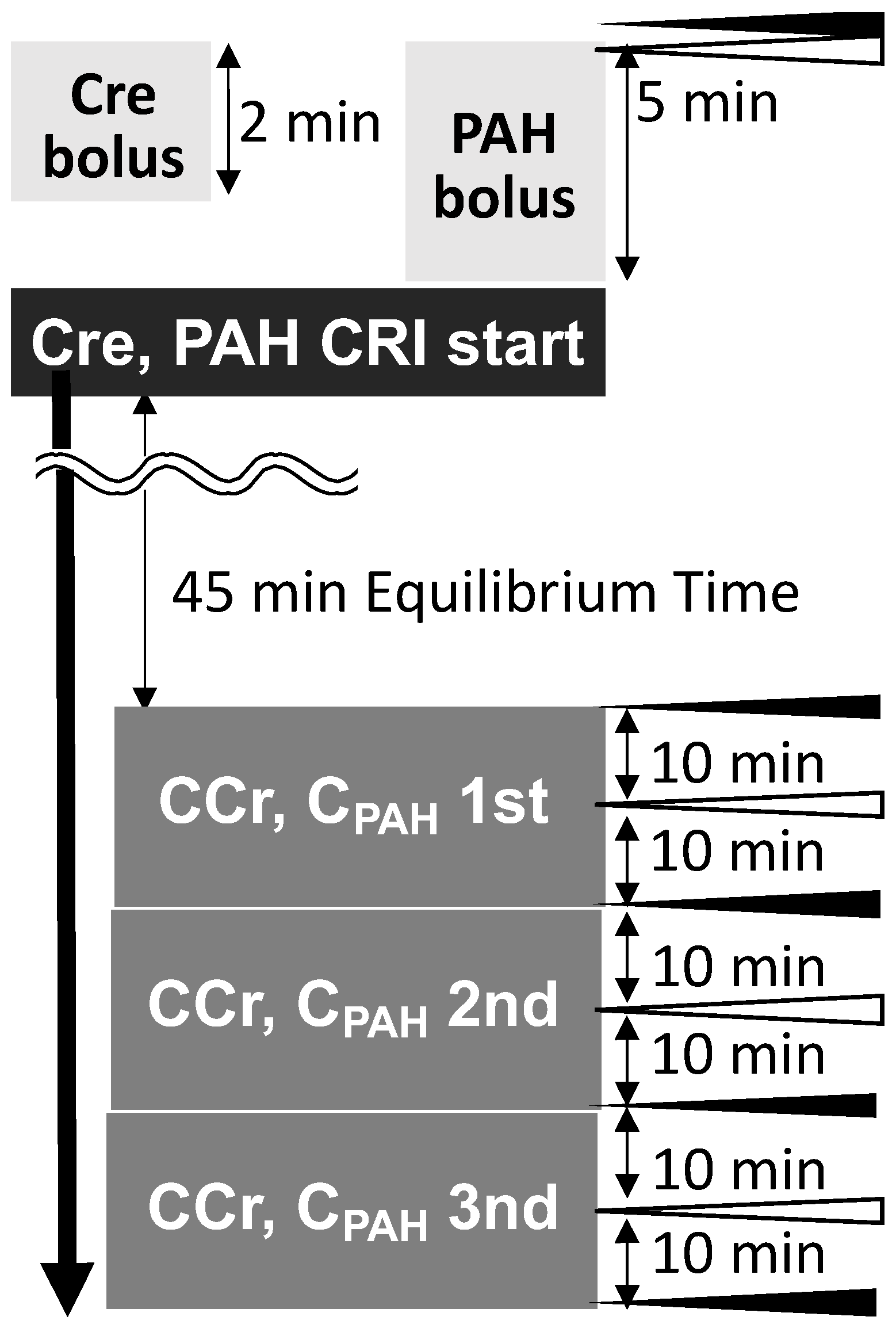

4.2. Study Protocol

4.3. CCr and CPAH

4.4. Blood Pressure

4.5. Plasma ANP Concentration

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yasue, H.; Yoshimura, M.; Sumida, H.; Kikuta, K.; Kugiyama, K.; Jougasaki, M.; Ogawa, H.; Okumura, K.; Mukoyama, M.; Nakao, K. Localization and Mechanism of Secretion of B-Type Natriuretic Peptide in Comparison with Those of A-Type Natriuretic Peptide in Normal Subjects and Patients with Heart Failure. Circulation 1994, 90, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knecht, M.; Pagel, I.; Langenickel, T.; Philipp, S.; Scheuermann-Freestone, M.; Willnow, T.; Bruemmer, D.; Graf, K.; Dietz, R.; Willenbrockm, R. Increased expression of renal neutral endopeptidase in severe heart failure. Life Sci. 2002, 71, 2701–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessup, M. Neprilysin inhibition—A novel therapy for heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1062–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Song, S.; Zhang, Y.; Mo, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, N.; Xia, Y.; Tse, G.; Liu, Y. Effect of angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors on left atrial remodeling and prognosis in heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzetti, S.; Scifo, C.; Abete, R.; Margonato, D.; Chioffim, M.; Rossi, J.; Pisani, M.; Passafaro, G.; Grillo, M.; Poggio, D.; et al. Short-term echocardiographic evaluation by global longitudinal strain in patients with heart failure treated with sacubitril/valsartan. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 964–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez, J.T. The Mechanism of Action of LCZ696. Card. Fail. Rev. 2016, 2, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saengklub, N.; Pirintr, P.; Nampimoon, T. Short-Term Effects of Sacubitril/valsartan on Echocardiographic Parameters in Dogs with Symptomatic Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 700230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbah, H.N.; Zhang, K.; Gupta, R.C.; Xu, J.; Singh-Gupta, V. Effects of Angiotensin-Neprilysin Inhibition in Canines with Experimentally Induced Cardiorenal Syndrome. J. Card. Fail. 2020, 11, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voors, A.A.; Gori, M.; Liu, L.C.; Claggett, B.; Zile, M.R.; Pieske, B.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Packer, M.; Shi, V.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; et al. Renal effects of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Packer, M.; Desai, A.S.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P.; Rizkala, A.R.; Rouleau, J.R.; Shi, V.C.; Solomon, S.D.; Swedberg, K.; et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kang, L.; Rong, K.; Zhang, Y.; Suo, Y.; Yuan, M.; Bao, O.; Shao, S.; Tse, G.; Li, R.; et al. Renal protective effects and mechanisms of the angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in mice with cardiorenal syndrome. Life Sci. 2021, 280, 119692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishio, H.; Ishii, A.; Yamada, H.; Mori, K.P.; Kato, Y.; Ohno, S.; Handa, T.; Sugioka, S.; Ishimura, T.; Ikushima, A.; et al. Sacubitril/valsartan ameliorates renal tubulointerstitial injury through increasing renal plasma flow in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes with aldosterone excess. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 2517–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uijl, E.; ‘t Hart, D.C.; Roksnoer, L.C.W.; Groningen, M.C.C.; van Veghel, R.; Garrelds, I.M.; de Vries, R.; van der Vlag, J.; Zietse, R.; Nijenhuis, T.; et al. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition confers renoprotection in rats with diabetes and hypertension by limiting podocyte injury. J. Hypertens. 2020, 38, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, B. Renal dysfunction complicating the treatment of hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 1256–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, G. Acute decompensated heart failure: The cardiorenal syndrome. Clevel. Clin. J. Med. 2006, 73, S8–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metra, M.; Cotter, G.; Gheorghiade, M.; Cas, L.D.; Voorset, A.A. The role of the kidney in heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2135–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, H.; Otomo, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Yamada, Y. Dual inhibition of SGLT2 and DPP-4 promotes natriuresis and improves glomerular hemodynamic abnormalities in KK/Ta-Ins2Akita mice with progressive diabetic kidney disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 635, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, S.P.; Prescott, M.F.; Camacho, A.; Iyer, S.R.; Maisel, A.S.; Felker, G.M.; Butler, J.; Piña, I.L.; Ibrahim, N.E.; Abbas, C.; et al. Atrial Natriuretic Peptide and Treatment with Sacubitril/Valsartan in Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2021, 9, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magliocco, G.; Thomas, A.; Desmeules, J.; Daali, Y. Phenotyping of Human CYP450 Enzymes by Endobiotics: Current Knowledge and Methodological Approaches. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 58, 1373–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayes-Genis, A.; Barallat, J.; Richards, A.M. A Test in Context: Neprilysin: Function, Inhibition, and Biomarker. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruilope, L.M.; Dukat, A.; Böhm, M.; Gong, J.; Lefkowitz, M.P. Blood-pressure reduction with LCZ696, a novel dual-acting inhibitor of the angiotensin II receptor and neprilysin: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, active comparator study. Lancet 2010, 375, 1255–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newhard, D.K.; Jung, S.; Winter, R.L.; Duran, S.H. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study of sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto) in dogs with cardiomegaly secondary to myxomatous mitral valve disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2018, 32, 1555–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyagawa, Y.; Akabane, R.; Sakatani, A.; Ogawa, M.; Nagakawa, M.; Miyakawa, H.; Takemura, N. Effects of telmisartan on proteinuria and systolic blood pressure in dogs with chronic kidney disease. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 133, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardeny, O.; Claggett, B.; Kachadourian, J.; Desai, A.S.; Packer, M.; Rouleau, J.; Zile, M.R.; Swedberg, K.; Lefkowitz, M.; Shi, V.; et al. Reduced loop diuretic use in patients taking sacubitril/valsartan compared with enalapril: The PARADIGM-HF trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, S.; Fukushima, R.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Hamabe, L.; Kim, S.; Yoshiyuki, R.; Fukayama, T.; Machida, N.; Tanaka, R. Comparative effect of carperitide and furosemide on left atrial pressure in dogs with experimentally induced mitral valve regurgitation. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2013, 27, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keene, B.W.; Atkins, C.E.; Bonagura, J.D.; Fox, P.R.; Häggström, J.; Fuentes, V.L.; Oyama, M.A.; Rush, J.E.; Stepien, R.; Uechi, M. ACVIM consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of myxomatous mitral valve disease in dogs. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 1127–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegger, G.A.; Elsner, D.; Kromer, E.P.; Daffner, C.; Forssmann, W.G.; Muders, F.; Pascher, E.W.; Kochsiek, K. Atrial natriuretic peptide in congestive heart failure in the dog: Plasma levels, cyclic guanosine monophosphate, ultrastructure of atrial myoendocrine cells, and hemodynamic, hormonal, and renal effects. Circulation 1988, 77, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konta, M.; Nagakawa, M.; Sakatani, A.; Akabane, R.; Miyagawa, Y.; Takemura, N. Evaluation of the inhibitory effects of telmisartan on drug-induced renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation in normal dogs. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2018, 20, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rittig, S.; Knudsen, U.B.; Nørgaard, J.P. Diurnal variation of plasma atrial natriuretic peptide in normals and patients with enuresis nocturna. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 1991, 51, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.D.J.; Lefebvre, H.P.; Concordet, D.; Laroute, V.; Ferré, J.P.; Braun, J.P.; Conchou, F.; Toutain, P.L. Plasma exogenous creatinine clearance test in dogs: Comparison with other methods and proposed limited sampling strategy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2002, 16, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Sugino, N. PAH clearance. Med. Tech. 1978, 6, 1282–1287. [Google Scholar]

| BL | D7 | D28 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCr (mL/min/kg) | 2.88 (1.87–3.19) | 2.81 (1.95–3.32) | 4.14 (3.91–5.42) * |

| 95% Confidence interval | 1.77–3.42 | 1.60–3.51 | 3.53–5.07 |

| CPAH (mL/min/kg) | 24.92 (16.02–29.61) | 26.43 (9.81–55.74) | 52.49 (34.87–84.48) |

| 95% Confidence interval | 13.55–28.53 | 6.15–58.98 | 21.0–75.73 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 146 (143–147) | 135 (128–144) | 127 (127–134) * |

| 95% Confidence interval | 141–149 | 127–143 | 123–142 |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg) | 98 (98–102) | 94 (93–105) | 97 (94–98) |

| 95% Confidence interval | 97–101 | 89–105 | 91–101 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76 (75–79) | 78 (67–86) | 80 (78–81) |

| 95% Confidence interval | 73–78 | 67–86 | 82–73 |

| Plasma ANP concentration (pg/mL) | 56 (30–59) | 74 (62–115) | 135 (50–173) |

| 95% Confidence interval | 26–80 | 44–133 | 36–198 |

| Urine Volume (mL/20 min) | 18.4 (18.1–28.1) | 29.4 (27.6–43.5) | 27.2 (14.9–111.0) |

| 95% Confidence interval | 13.2–28.4 | 20.9–44.9 | 3.8–76.5 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 96 (92–104) | 116 (112–128) | 100 (84–108) |

| 95% Confidence interval | 83–120 | 98–139 | 84–109 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ishizaka, M.; Yamamori, Y.; Hsu, H.-H.; Miyagawa, Y.; Takemura, N.; Ogawa-Yasumura, M. Study on the Effects of Angiotensin Receptor/Neprilysin Inhibitors on Renal Haemodynamics in Healthy Dogs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116169

Ishizaka M, Yamamori Y, Hsu H-H, Miyagawa Y, Takemura N, Ogawa-Yasumura M. Study on the Effects of Angiotensin Receptor/Neprilysin Inhibitors on Renal Haemodynamics in Healthy Dogs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(11):6169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116169

Chicago/Turabian StyleIshizaka, Mio, Yurika Yamamori, Huai-Hsun Hsu, Yuichi Miyagawa, Naoyuki Takemura, and Mizuki Ogawa-Yasumura. 2024. "Study on the Effects of Angiotensin Receptor/Neprilysin Inhibitors on Renal Haemodynamics in Healthy Dogs" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 11: 6169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116169

APA StyleIshizaka, M., Yamamori, Y., Hsu, H.-H., Miyagawa, Y., Takemura, N., & Ogawa-Yasumura, M. (2024). Study on the Effects of Angiotensin Receptor/Neprilysin Inhibitors on Renal Haemodynamics in Healthy Dogs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(11), 6169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116169