Exploring the Neuroprotective Potential of N-Methylpyridinium against LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation: Insights from Molecular Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

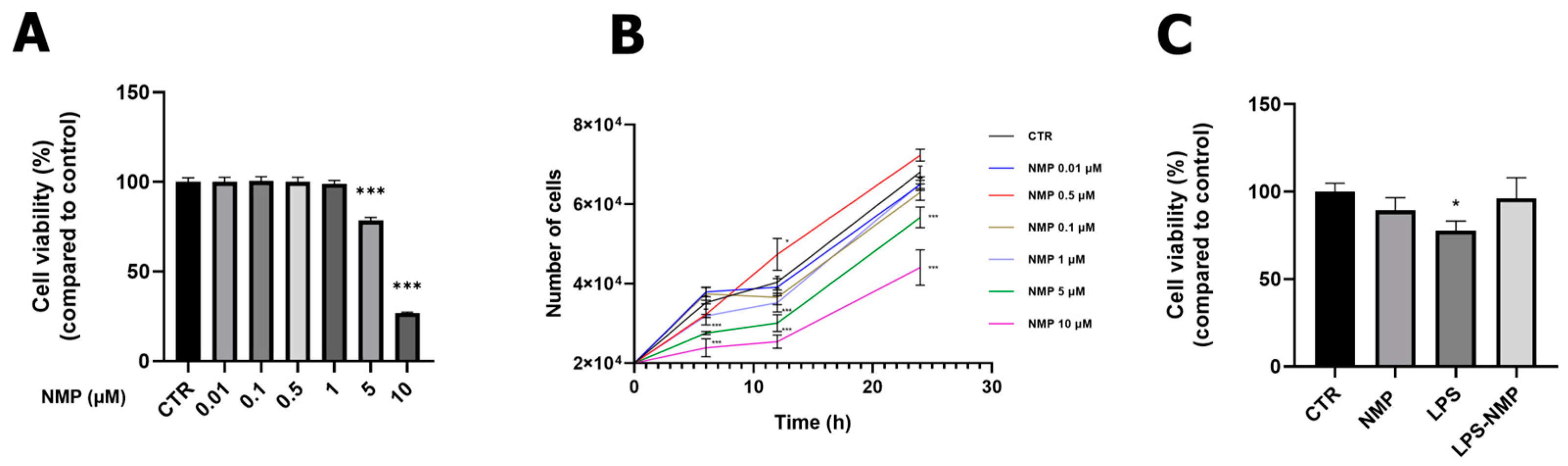

2.1. Effects of NMP on Cell Viability

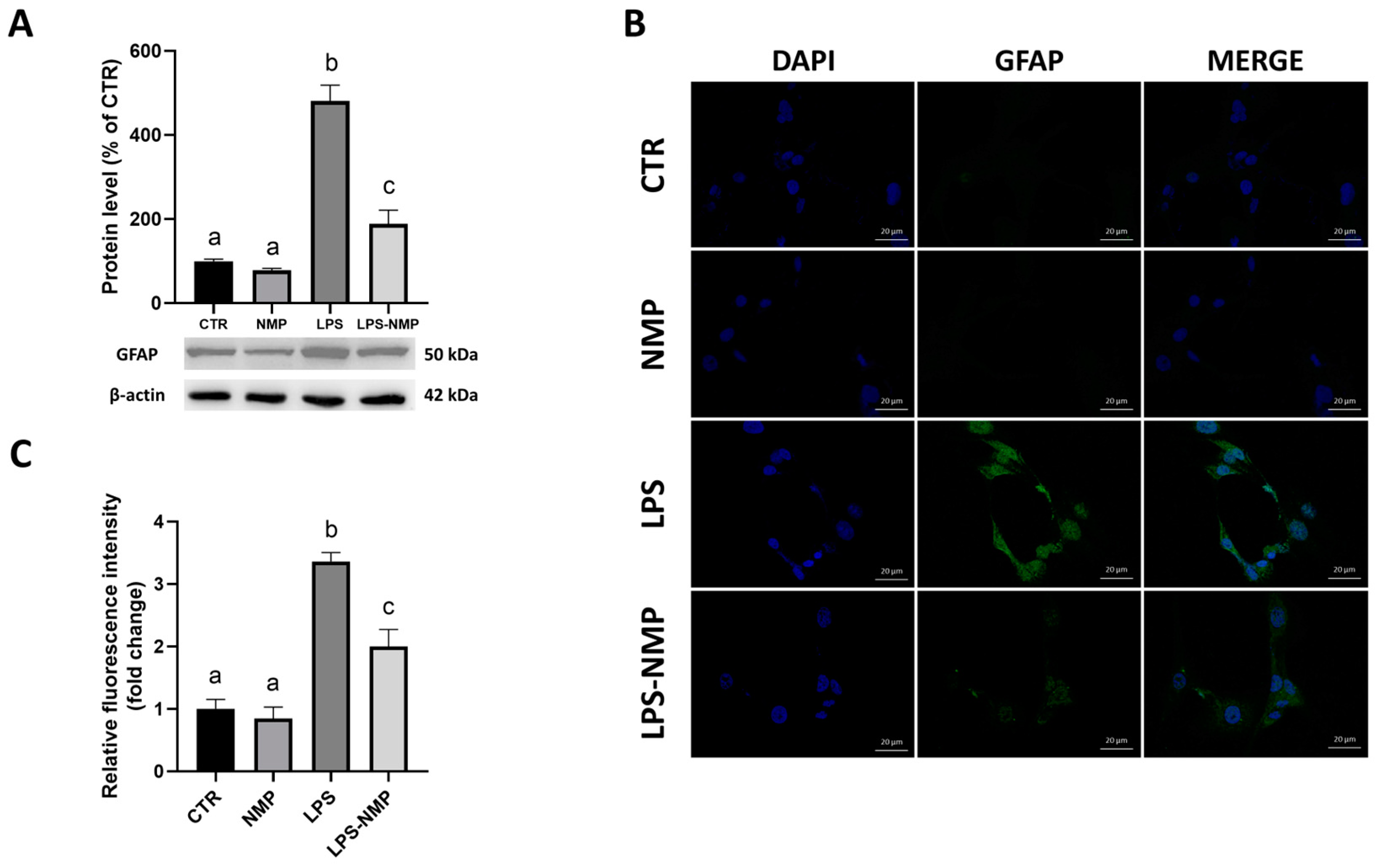

2.2. NMP Inhibits LPS-Induced Inflammation in Reactive Astrocytes

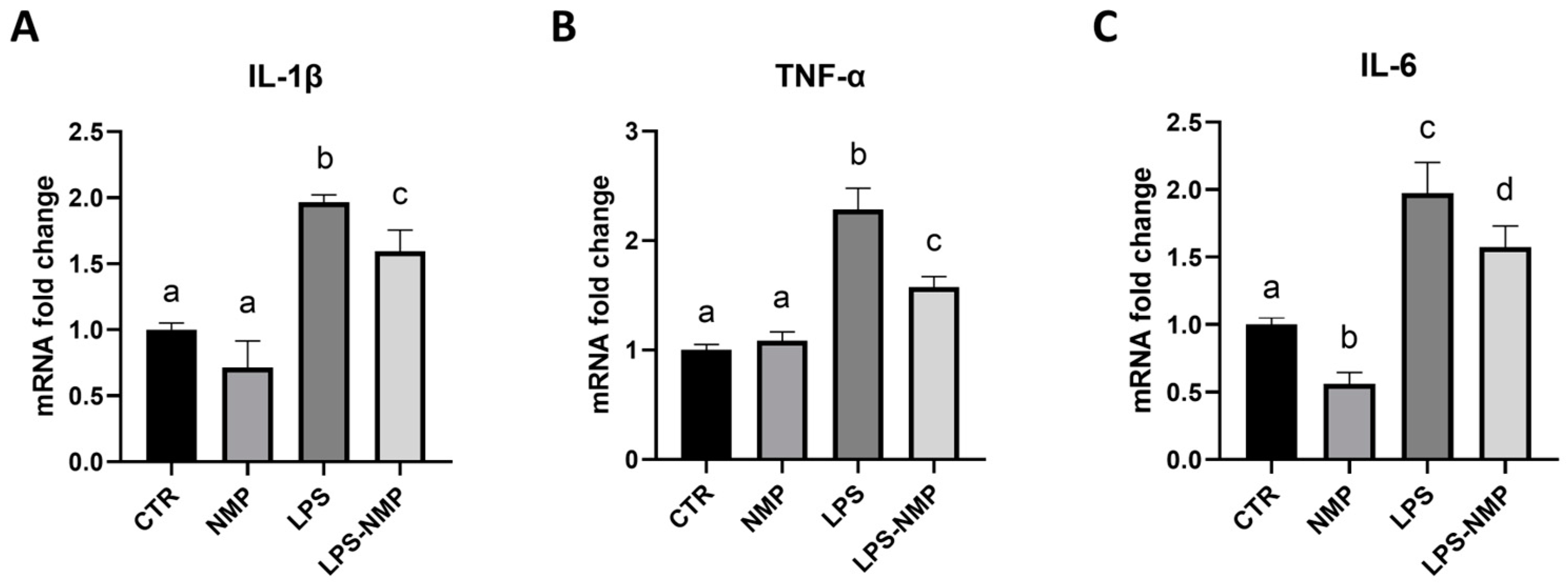

2.3. NMP Regulates the Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in U87MG Cells

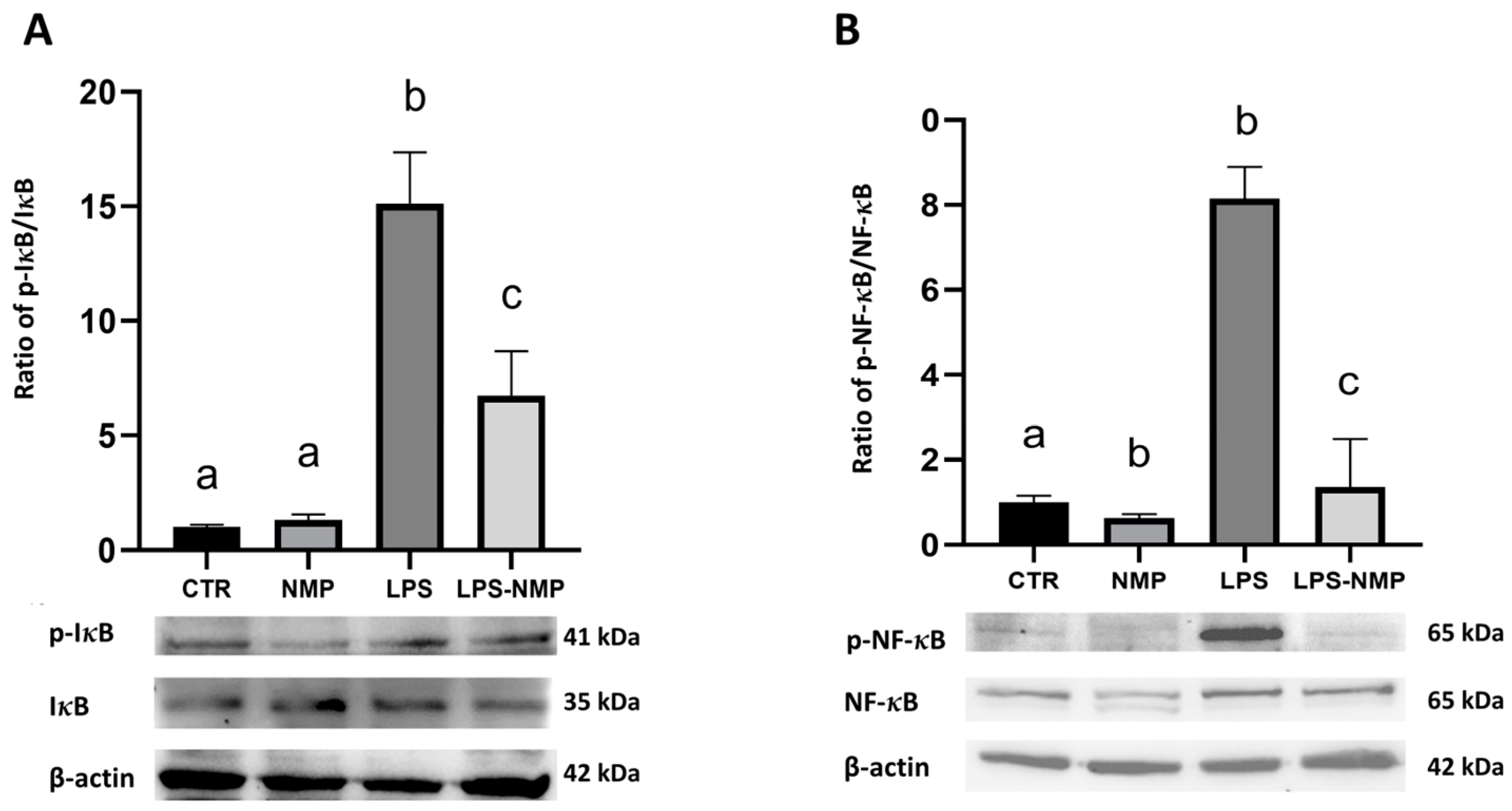

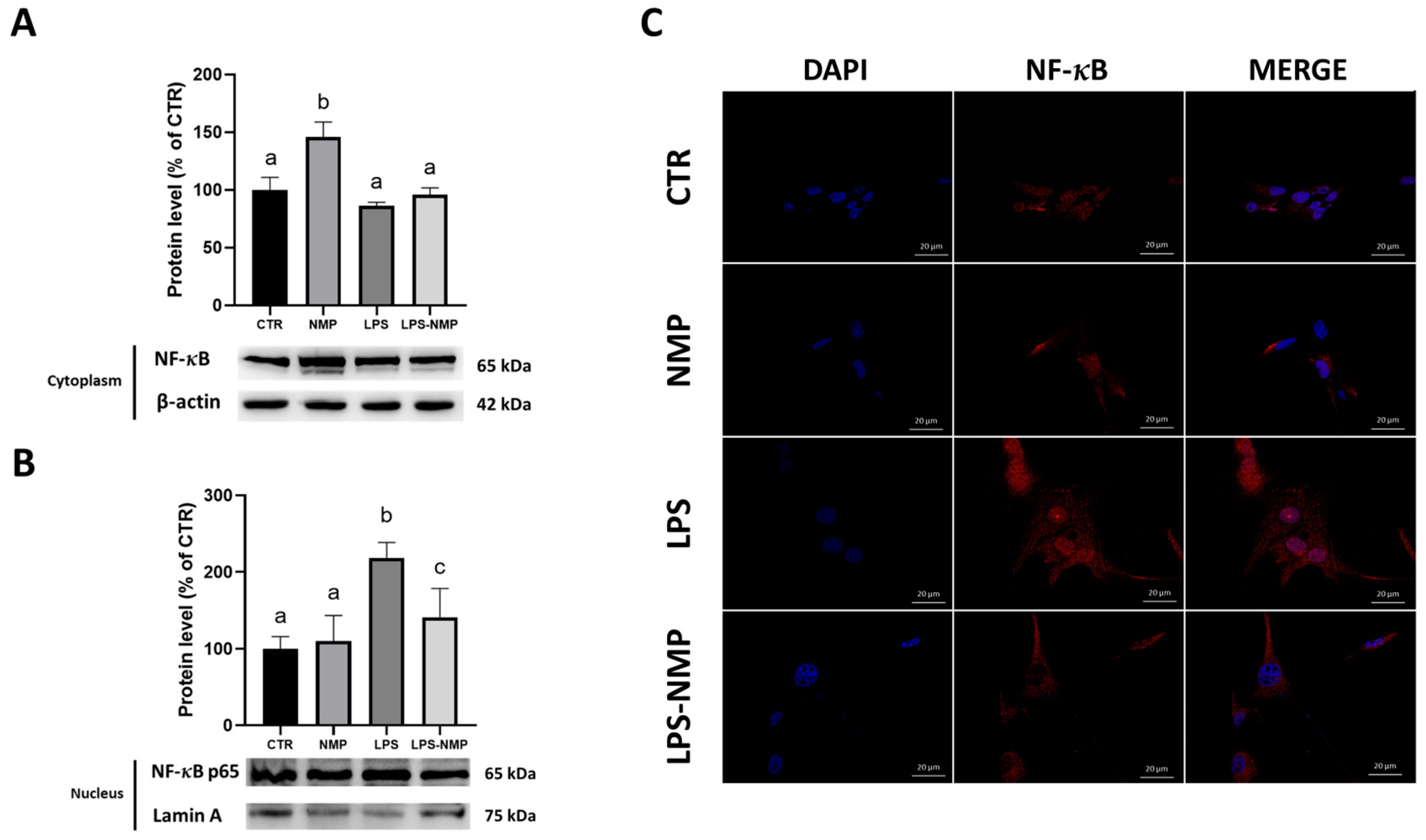

2.4. NMP Acts at the Level of the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in U87MG Cells

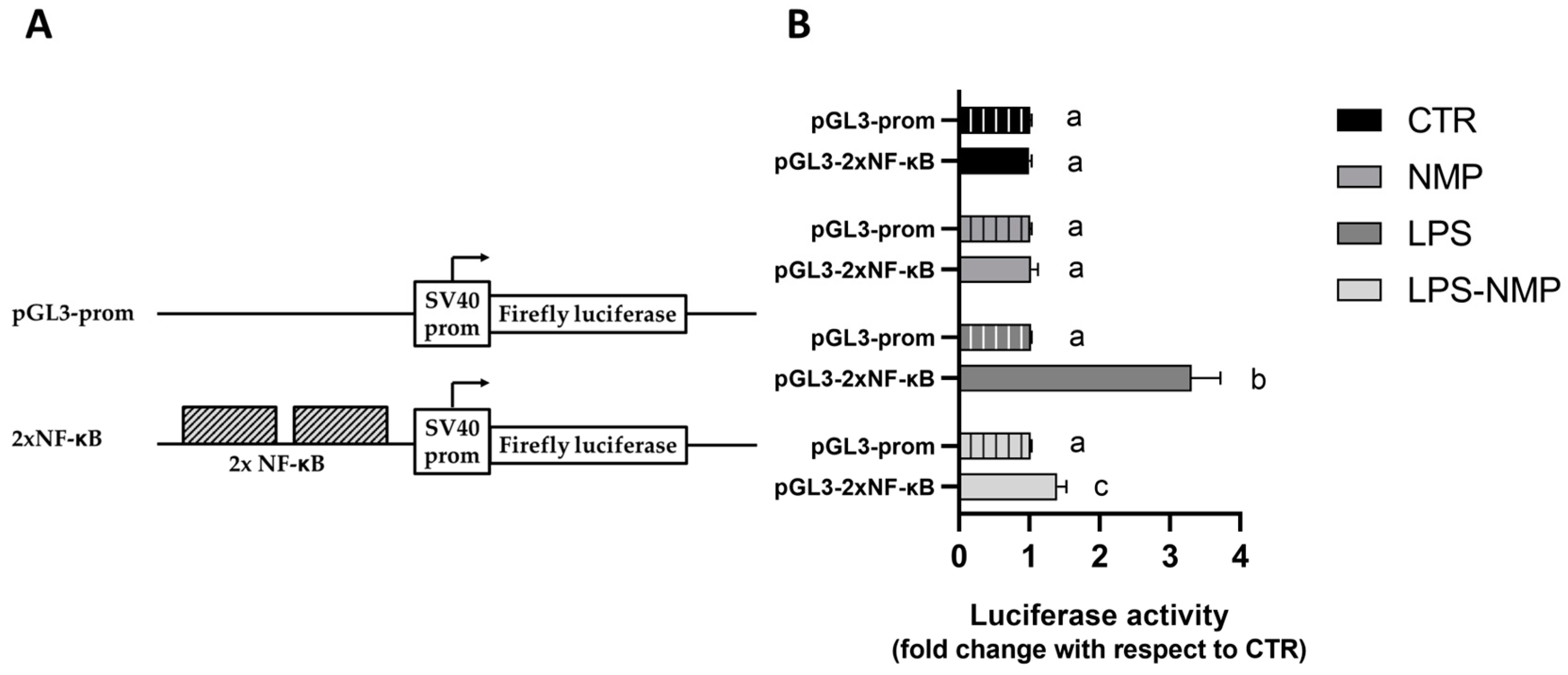

2.5. NMP Inhibits the Transactivation Activity of NF-κB Transcription Factor in LPS-Treated Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Treatment

4.2. Cell Viability Assay

4.3. Cell Counting

4.4. Immunofluorescence Assay

4.5. Real-Time PCR

4.6. Western Blotting Analysis

4.7. Cell Transfection and Luciferase Assay

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kölliker-Frers, R.; Udovin, L.; Otero-Losada, M.; Kobiec, T.; Herrera, M.I.; Palacios, J.; Razzitte, G.; Capani, F. Neuroinflammation: An Integrating Overview of Reactive-Neuroimmune Cell Interactions in Health and Disease. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 9999146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vizuete, A.F.K.; Fróes, F.; Seady, M.; Zanotto, C.; Bobermin, L.D.; Roginski, A.C.; Wajner, M.; Quincozes-Santos, A.; Gonçalves, C.A. Early effects of LPS-induced neuroinflammation on the rat hippocampal glycolytic pathway. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. Microglia function in the central nervous system during health and neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Zheng, H.; Shao, X.; Wang, W.; Yao, Q.; Li, Z. Excitotoxicity of TNFalpha derived from KA activated microglia on hippocampal neurons in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurochem. 2010, 114, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simi, A.; Lerouet, D.; Pinteaux, E.; Brough, D. Mechanisms of regulation for interleukin-1 b in neurodegenerative disease. Neuropharmacology 2007, 52, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ransohoff, R.M. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science 2016, 353, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Q.; He, L.; Wang, M.; Zuo, S.; Gao, H.; Feng, Y.; Du, L.; Luo, Y.; Li, J. Comparison of the TLR4/NFκB and NLRP3 signalling pathways in major organs of the mouse after intravenous injection of lipopolysaccharide. Pharm. Biol. 2019, 57, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Peng, X.; He, Y.; Ruganzu, J.B.; Yang, W. Tanshinone IIA suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammatory responses through NF-κB/MAPKs signaling pathways in human U87 astrocytoma cells. Brain Res. Bull. 2020, 164, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvello, R.; Lofrumento, D.D.; Perrone, M.G.; Cianciulli, A.; Salvatore, R.; Vitale, P.; De Nuccio, F.; Giannotti, L.; Nicolardi, G.; Panaro, M.A.; et al. Highly Selective Cyclooxygenase-1 Inhibitors P6 and Mofezolac Counteract Inflammatory State both In Vitro and In Vivo Models of Neuroinflammation. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bułdak, R.J.; Hejmo, T.; Osowski, M.; Bułdak, Ł.; Kukla, M.; Polaniak, R.; Birkner, E. The Impact of Coffee and Its Selected Bioactive Compounds on the Development and Progression of Colorectal Cancer In Vivo and In Vitro. Molecules 2018, 23, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettler, U.; Sommerfeld, K.; Volz, N.; Pahlke, G.; Teller, N.; Somoza, V.; Lang, R.; Hofmann, T.; Marko, D. Coffee constituents as modulators of Nrf2 nuclear translocation and ARE (EpRE)-dependent gene expression. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskelinen, M.H.; Ngandu, T.; Tuomilehto, J.; Soininen, H.; Kivipelto, M. Midlife coffee and tea drinking and the risk of late-life dementia: A population-based CAIDE study. J. Alzheimer Dis. 2009, 19, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.; Dieminger, N.; Beusch, A.; Lee, Y.M.; Dunkel, A.; Suess, B.; Skurk, T.; Wahl, A.; Hauner, H.; Hofmann, T. Bioappearance and pharmacokinetics of bioactives upon coffee consumption. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 8487–8503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascherio, A.; Zhang, S.M.; Hernan, M.A.; Kawachi, I.; Colditz, G.A.; Speizer, F.E.; Willett, W.C. Prospective study of caffeine consumption and risk of Parkinson’s diseases in men and women. Ann. Neurol. 2001, 50, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarta, S.; Scoditti, E.; Carluccio, M.A.; Calabriso, N.; Santarpino, G.; Damiano, F.; Siculella, L.; Wabitsch, M.; Verri, T.; Favari, C.; et al. Coffee Bioactive N-Methylpyridinium Attenuates Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α-Mediated Insulin Resistance and Inflammation in Human Adipocytes. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dludla, P.V.; Cirilli, I.; Marcheggiani, F.; Silvestri, S.; Orlando, P.; Muvhulawa, N.; Moetlediwa, M.T.; Nkambule, B.B.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Hlengwa, N.; et al. Potential Benefits of Coffee Consumption on Improving Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Healthy Individuals and Those at Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Molecules 2023, 28, 6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadler, R.H.; Varga, N.; Hau, J.; Vera, F.A.; Welti, D.H. Alkylpyridiniums. 1. Formation in model systems via thermal degradation of trigonelline. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somoza, V.; Lindenmeier, M.; Wenzel, E.; Frank, O.; Erbersdobler, H.F.; Hofmann, T. Activity-guided identification of a chemopreventive compound in coffee beverage using in vitro and in vivo techniques. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6861–6869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, A.; Hochkogler, C.M.; Lang, R.; Bytof, G.; Lantz, I.; Hofmann, T.; Somoza, V. N-methylpyridinium, a degradation product of trigonelline upon coffee roasting, stimulates respiratory activity and promotes glucose utilization in HepG2 cells. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, L.; Tassotti, M.; Rosi, A.; Martini, D.; Antonini, M.; Dei Cas, A.; Bonadonna, R.; Brighenti, F.; Del Rio, D.; Mena, P. Absorption, Pharmacokinetics, and Urinary Excretion of Pyridines After Consumption of Coffee and Cocoa-Based Products Containing Coffee in a Repeated Dose, Crossover Human Intervention Study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2020, 64, e2000489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, C.F.; Rowe, D.B.; Halliday, G.M. An inflammatory review of Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2002, 68, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teismann, P.; Tieu, K.; Cohen, O.; Choi, D.K.; Wu, D.C.; Marks, D.; Vila, M.; Jackson Lewis, V.; Przedborski, S. Pathogenic role of glial cells in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2003, 18, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T.; Tago, K.; Miyata, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Misawa, H.; Kobata, K.; Nakazawa, Y.; Tamura, H.; Funakoshi-Tago, M. Suppression of Neuroinflammation by Coffee Component Pyrocatechol via Inhibition of NF-κB in Microglia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.B.; Miao, J.F.; Zhu, Y.M.; Deng, Y.E.; Zou, S.X. Protective effect of retinoid against endotoxin-induced mastitis in rats. Inflamm. Res. 2009, 58, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakpour, S.; Wilhelmsen, K.; Hellman, J. Vascular endothelial cell Toll-like receptor pathways in sepsis. Innate Immun. 2015, 21, 827–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, K.; Xu, W.; Xiang, X.; Xia, S. The regulatory effect of oxymatrine on the TLR4/MyD88/NF-kappa B signaling pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced MS1 cells. Phytomedicine 2017, 36, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harikrishnan, H.; Jantan, I.; Haque, M.A.; Kumolosasi, E. Anti-inflammatory effects of Phyllanthus amarus Schum. & Thonn. through inhibition of NF-kappa B, MAPK, and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways in LPS-induced human macrophages. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R.G.; Hayden, M.S.; Ghosh, S. NF-kappa B, inflammation, and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Hou, D.; Wei, Z.; Zhu, J.; Lu, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Qiao, G.; Liu, N. Tanshinone IIA attenuates cerebral aneurysm formation by inhibiting the NF-kappa B-mediated inflammatory response. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, K.W.; Zhang, T.; Fu, H.; Liu, G.X.; Wang, X.M. Schisandrin B exerts anti-neuroinflammatory activity by inhibiting the Toll-like receptor 4-dependent MyD88/IKK/NF-kappa B signaling pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced microglia. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 692, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistyakov, D.V.; Azbukina, N.V.; Lopachev, A.V.; Kulichenkova, K.N.; Astakhova, A.A.; Sergeeva, M.G. Rosiglitazone as a modulator of TLR4 and TLR3 signaling pathways in rat primary neurons and astrocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunetti, M.; Castiglia, S.; Rustichelli, D.; Mareschi, K.; Sanavio, F.; Muraro, M.; Signorino, E.; Castello, L.; Ferrero, I.; Fagioli, F. Validation of analytical methods in GMP: The disposable Fast Read 102® device, an alternative practical approach for cell counting. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | Sequences (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| Gapdh | F: ATGGCCTTCCGTGTCCCCAC R: ACGCCTGCTTCACCACCTTC |

| TNF-α | F: CCCGAGTGACAAGCCTGAG R: GATGGCAGAGAGGAGGTTGAC |

| IL-1β | F: CTGTCCTGCGTGTTGAAAGA R: AGTTATATCCTGGCCGCCTT |

| IL-6 | F: ACAGCCACTCACCTCTTCAG R: CCATCTTTTTCAGCCATCTTT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giannotti, L.; Di Chiara Stanca, B.; Spedicato, F.; Stanca, E.; Damiano, F.; Quarta, S.; Massaro, M.; Siculella, L. Exploring the Neuroprotective Potential of N-Methylpyridinium against LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation: Insights from Molecular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116000

Giannotti L, Di Chiara Stanca B, Spedicato F, Stanca E, Damiano F, Quarta S, Massaro M, Siculella L. Exploring the Neuroprotective Potential of N-Methylpyridinium against LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation: Insights from Molecular Mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(11):6000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116000

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiannotti, Laura, Benedetta Di Chiara Stanca, Francesco Spedicato, Eleonora Stanca, Fabrizio Damiano, Stefano Quarta, Marika Massaro, and Luisa Siculella. 2024. "Exploring the Neuroprotective Potential of N-Methylpyridinium against LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation: Insights from Molecular Mechanisms" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 11: 6000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116000

APA StyleGiannotti, L., Di Chiara Stanca, B., Spedicato, F., Stanca, E., Damiano, F., Quarta, S., Massaro, M., & Siculella, L. (2024). Exploring the Neuroprotective Potential of N-Methylpyridinium against LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation: Insights from Molecular Mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(11), 6000. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25116000